Abstract

Aims

Cardiorespiratory fitness is an important predictor of cardiovascular morbidity and mortality. Both red cell distribution width (RDW) and inflammatory markers like C-reactive protein (CRP) have been shown to predict adverse outcomes in patients with heart disease.

Methods

We utilized pooled data from NHANES 1999–2004 to assess cardiorespiratory fitness in healthy adults 12–49 years old using submaximal exercise. The primary outcome was the estimated maximal oxygen uptake (VO2max). Low fitness was defined as VO2max < 20th percentile of age- and gender-based reference category.

Results

In our study, we estimated 21.2% of individuals had low fitness. Elevated RDW (>13%) was encountered in 20.4% subjects with low fitness as compared to 14.0% subjects in the control group (p < 0.001). Similarly, elevated CRP (>0.5 mg/dL) was found among 17.4% subjects with low fitness as compared to 12.4% subjects in the control group (p < 0.001). Adjusted analysis demonstrated a dose–response relationship between low cardiorespiratory fitness and increasing RDW or CRP.

Conclusion

In a large representative database of general US population, we observed a significant association between elevated RDW and elevated CRP with low cardiorespiratory fitness.

Keywords: Red cell distribution width, C-reactive protein, National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, Complex survey analysis, Exercise capacity

1. Introduction

Although there has been a substantial decline in the mortality attributed to cardiovascular disease over the last three decades, it remains the leading cause of death in the United States.1 Several large studies have demonstrated a consistent, inverse relationship between cardiorespiratory fitness measured using exercise capacity and cardiovascular disease outcomes, including long-term mortality.2–5 This association has been demonstrated in subjects with or without cardiovascular disease at baseline, after adjustment for traditional cardiovascular risk factors.5 Among subjects with prevalent risk factors including hypercholesterolemia, hypertension, diabetes or active smoking, the presence of high exercise capacity in midlife was found to substantially reduce the risk of long-term morbidity due to presence of risk factors.3

Several hypotheses have been generated regarding pathophysiologic mechanisms preceding the genesis of cardiovascular disease. Chronic subclinical inflammation is a well-established entity that is believed to predispose to adverse cardiovascular events.6–8 In addition, high oxidative stress has been shown to be a potential contributing mechanism in the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease.9 Red cell distribution width (RDW) is a recently described novel biomarker that has been shown to be predictive of adverse outcomes in multiple cardiovascular disease settings including stable coronary artery disease, chronic heart failure and acute myocardial infarction.10–13 Although the plausible pathobiological mechanisms explaining the relationship of RDW with adverse cardiovascular outcomes are yet to be elucidated, both inflammation and oxidative stress are believed to play a role.7,14

Although there is ample evidence to suggest that low exercise capacity predicts adverse cardiovascular outcomes, the evidence surrounding the determinants of low exercise capacity are rather scarce. We aimed to study the association between RDW, inflammatory markers and low exercise capacity using a large national database of the non-institutionalized population representative of the general US population.

2. Methods

2.1. Study population

This study analyzed pooled National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) data from 1999–2000, 2001–2002 and 2003–2004.15 NHANES is an ongoing cross-sectional survey of the civilian, non-institutionalized US population that provides a representative sample for calculation estimates of national health and nutritional status. Survey participants aged 12–49 years without physical limitations or pre-existing cardiovascular or pulmonary diseases were eligible for cardiorespiratory fitness testing.

2.2. Estimation of exercise capacity

Cardiorespiratory fitness was measured using submaximal exercise testing. Based on the subject's age, body mass index (BMI), gender and self-reported level of physical activity, the system calculated the predicted maximal oxygen consumption (predicted VO2max) for each participant. Subsequently, each participant was assigned to one of eight standardized treadmill protocols based on the predicted VO2max [Table 1]. The goal of each protocol was to elicit a heart rate >75% of age predicted maximum heart rate (220-age) by test termination. Each protocol included a 2-min warm-up, two 3-min exercise stages and a 2-min cool-down period.

Table 1.

Determination of exercise protocol based on predicted VO2max calculated using age, gender, body mass index and physical activity score. Based on the predicted VO2max, each participant was assigned to an exercise protocol with a pre-determined speed (measured in miles per hour) and grade (percent incline). The speed and the grade for each stage of the test was chosen such that the activity level would correspond to 45% of predicted VO2max, 55% of predicted VO2max and 75% of predicted VO2max in the warm-up phase, stage 1 and stage 2 of the testing protocol respectively.

| Predicted VO2max (mL/kg/min) | Exercise protocol number | Warm-up |

Stage 1 |

Stage 2 |

Recovery |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Speed (mph) | Grade (%) | Speed (mph) | Grade (%) | Speed (mph) | Grade (%) | Speed (mph) | Grade (%) | ||

| <20 | 1 | 1.7 | 0 | 2.1 | 0.5 | 2.1 | 4.5 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 20–24 | 2 | 2.0 | 1.0 | 2.3 | 2.0 | 2.3 | 6.5 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 25–29 | 3 | 2.2 | 2.0 | 2.7 | 3.0 | 2.7 | 7.5 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 30–34 | 4 | 2.7 | 2.0 | 3.1 | 4.0 | 3.1 | 8.5 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 35–39 | 5 | 3.0 | 3.0 | 3.7 | 4.0 | 3.7 | 8.0 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 40–44 | 6 | 3.1 | 3.5 | 3.7 | 5.5 | 3.7 | 10.0 | 2.0 | 0 |

| 45–49 | 7 | 3.2 | 5.0 | 3.7 | 7.0 | 3.7 | 12.5 | 2.0 | 0 |

| ≥50 | 8 | 3.6 | 5.0 | 3.7 | 8.5 | 3.7 | 14.5 | 2.0 | 0 |

Heart rate was continuously monitored using four electrodes connected to the subject's chest and abdomen. Blood pressure was measured at the end of warm-up, each exercise stage and each minute of the cool-down period. Each participant was asked to rate the level of exertion at the end of warm-up and both exercise stages using a Borg scale. This was termed Rating of Perceived Exertion (RPE).

The primary outcome of exercise testing was the determination of estimated maximal oxygen uptake (estimated VO2max). Since the relationship between heart rate and oxygen consumption is linear during exercise, it is possible to estimate the VO2max by measuring the heart rate response to known levels of submaximal work.

The level of cardiorespiratory fitness was categorized low, moderate and high fitness based on age- and gender-specific cut-points of estimated VO2max. The reference cut-points that were utilized for adults 20–49 years of age were based on the data from the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study (ACLS).16,17 Low-fitness level was defined as estimated VO2max below the 20th percentile for the same gender and age group. Moderate fitness level was defined as a value between the 20th and 59th percentile and high fitness level was defined as a value above the 60th percentile of the respective age and gender group. The reference standards utilized for the adolescents and young adults 12–19 years were based on the criteria used in the FITNESSGRAM program.18,19

2.3. Measurement of RDW and inflammatory markers

We utilized C-reactive protein (CRP) as the surrogate marker for overall body inflammation in our study and measured CRP on stored venipuncture samples by latex-enhanced nephelometry with results reported within the range of 0.01–20 mg/dL. Elevated CRP was defined as CRP concentration ≥0.5 mg/dL. RDW was measured using the Beckman Coulter method of counting and sizing, in combination with an automatic diluting and mixing device for sample processing, and a single beam photometer for hemoglobinometry. Mathematically, RDW = (standard deviation of red cell volume/mean cell volume) × 100, with higher RDW implying a greater variety in red cell sizes. Elevated RDW was defined as measured RDW ≥ 13%.

2.4. Measurement of other confounders and mediators

We defined hypertension as systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mmHg, diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mmHg, self-reported diagnosis of hypertension by a physician, or self-reported use of antihypertensive medication. Hyperlipidemia was defined as a total blood cholesterol >200 mg/dL, self-reported diagnosis of hyperlipidemia by a physician, or self-reported use of cholesterol lowering medication. Diabetes was defined as a self-reported diagnosis of diabetes by a physician or use of insulin or oral hypoglycemic medication.

Smoking status was determined using serum cotinine measurements along with the questionnaire items including “Have you smoked at least 100 cigarettes in your entire life?” and “Do you now smoke cigarettes?” In the NHANES, serum cotinine was measured using isotope dilution, high performance liquid chromatography/atmospheric pressure chemical ionization tandem mass spectrometry.15 Active smokers were defined as self-reported active cigarette smoking or measured serum cotinine ≥10 ng/mL. All non-active smokers by self-report were classified as former smokers and never smokers based on survey question responses.

Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) was estimated using the modification of diet in renal disease study formula20,21 based on age, serum creatinine, race and gender. Serum creatinine was standardized across surveys based on previously published calibration equations.22 Chronic kidney disease (CKD) was defined as an estimated GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2. BMI was calculated from current height and weight using the equation BMI = weight (kg)/[height (m)]2.

Since RDW is directly affected by anemia, we adjusted our analyses for hemoglobin concentration and serum ferritin concentration. Hemoglobin was measured using standard hemoglobinometry described above. Ferritin was measured by using the Bio-Rad Laboratories' “QuantImune Ferritin IRMA” kit (Bio-Rad Laboratories, 1986), which is a single-incubation two-site immunoradiometric assay.15

2.5. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using Stata v 12.0 (Stata Corp., College Station, TX, USA). Data from NHANES 1999–2004 surveys were pooled using standard methods, and subsequently, 6-year combined weights were calculated. Survey statistics traditionally used to analyze complex semi-random survey designs were employed to analyze these data. Multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed with low fitness as the outcome measure in the regression models to obtain adjusted effect estimates and their 95% confidence intervals (CIs) after accounting for the above-mentioned confounders. For the purpose of our analysis, subjects with moderate or high level of fitness were termed as “controls.” All statistical tests were two-tailed and a p-value <0.05 was deemed significant.

3. Results

Data from 8324 individuals representative of 84 million US residents was available for analysis. Table 1 demonstrates the baseline characteristics of the study population. The prevalence (SE) of low cardiorespiratory fitness was estimated as 21.2 (0.9)%. The population with low-level fitness was significantly younger in comparison to the control population (p < 0.001). There was a higher prevalence of lower cardiorespiratory fitness among females as compared to males (p < 0.001). Subjects with lower cardiorespiratory fitness were more likely to be black or Mexican-American than white. As evident in Table 2, there were no significant differences in the prevalence of hypertension, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, CKD or active smoking between the two study groups. However, the mean BMI in the low-fitness group was significantly higher in comparison to the control group (p < 0.001). Thirty percent of the individuals with low fitness had BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2, as compared to only 18.8% of subjects with moderate-high level fitness (p < 0.001).

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics.

| Low fitness (n = 2394) | Controls (n = 5930) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Prevalence | 21.2 (0.9) | 78.8 (0.9) | |

| Males | 48.3 (1.4) | 53.2 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Females | 51.7 (1.4) | 46.8 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Mean (SE) age (years) | 24.5 (0.4) | 30.0 (0.2) | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| Whites | 60.7 (2.9) | 70.2 (1.4) | <0.001 |

| Blacks | 15.7 (1.7) | 10.6 (0.9) | <0.001 |

| Mexican-Americans | 11.9 (1.7) | 9.5 (0.9) | 0.006 |

| Others | 11.7 (1.6) | 9.6 (1.0) | 0.06 |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 5.8 (1.0) | 5.9 (0.4) | 0.9 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 8.7 (1.1) | 10.3 (0.5) | 0.2 |

| Diabetes | 1.5 (0.5) | 0.9 (0.2) | 0.2 |

| Mean (SE) BMI (kg/m2) | 27.3 (0.2) | 25.6 (0.1) | <0.001 |

| BMI categories | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 41.5 (1.7) | 53.0 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | 28.5 (13.6) | 28.3 (1.0) | 0.9 |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 30.0 (1.5) | 18.8 (0.8) | <0.001 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 0.4 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.3) | 0.09 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never-smoker | 50.3 (2.9) | 50.6 (1.5) | 0.9 |

| Mean (SE) serum cotinine | 0.36 (0.07) | 0.27 (0.02) | 0.2 |

| Former-smoker | 13.1 (1.8) | 14.2 (0.8) | 0.3 |

| Mean (SE) serum cotinine | 0.36 (0.1) | 0.38 (0.05) | 0.6 |

| Active-smoker | 36.5 (2.4) | 35.2 (1.3) | 0.4 |

| Mean (SE) serum cotinine | 175.1 (8.5) | 178.3 (5.3) | 0.6 |

3.1. CRP and cardiorespiratory fitness

Table 3 demonstrates the proportion of patients with elevated CRP (≥0.5 mg/dL) stratified by various demographic and clinical characteristics. The prevalence (SE) of elevated CRP was 17.4 (1.1)% in the low-fitness group as compared to 12.4 (0.6)% in the control population (p < 0.001). Interestingly, the prevalence of elevated CRP was significantly higher among females in comparison to males (p < 0.001 for both low-fitness and control groups). A significantly higher prevalence of elevated CRP in the low-fitness population was encountered in several strata including blacks, Mexican-Americans, hypertensive subjects and obese subjects with BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2.

Table 3.

Proportion of subjects with high CRP (≥0.5 mg/dL) between the study groups.

| Low fitness (n = 2394) | Controls (n = 5930) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort | 17.4 (1.1) | 12.4 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Males | 10.5 (1.3) | 8.3 (0.7) | 0.09 |

| Females | 24.1 (2.1) | 17.2 (1.0) | 0.004 |

| Race | |||

| Whites | 16.2 (2.9) | 12.0 (1.3) | 0.3 |

| Blacks | 22.2 (1.9) | 13.0 (1.9) | <0.001 |

| Mexican-Americans | 20.5 (1.7) | 15.7 (1.9) | 0.002 |

| Others | 14.0 (2.2) | 11.5 (2.2) | 0.9 |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 34.9 (3.0) | 21.4 (1.6) | 0.003 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 27.8 (5.1) | 19.0 (1.8) | 0.6 |

| BMI categories | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 6.4 (1.4) | 6.5 (0.6) | 0.9 |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | 12.6 (2.4) | 12.1 (1.0) | 0.8 |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 37.0 (2.3) | 29.3 (1.6) | 0.004 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 14.9 (3.2) | 19.0 (2.5) | 0.3 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never-smoker | 23.6 (2.9) | 14.1 (1.1) | 0.002 |

| Former-smoker | 34.2 (1.8) | 12.4 (2.5) | 0.003 |

| Active-smoker | 21.6 (2.4) | 14.6 (1.4) | 0.03 |

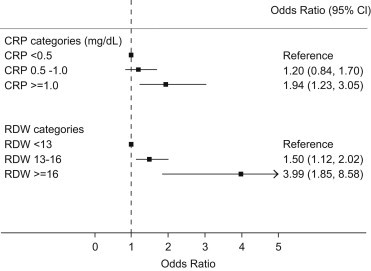

Using multivariate logistic regression analysis, we observed that subjects with elevated CRP had significantly higher odds of low cardiorespiratory fitness in comparison to those with normal CRP. Fig. 1 demonstrates a dose–response relationship between increasing CRP and the prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness. We observed that subjects with CRP ≥ 1.0 mg/dL had a 94% (95% CI: 23%–205%) higher odds of low cardiorespiratory fitness in comparison to those with serum CRP concentration <0.5 mg/dL.

Fig. 1.

Adjusted odds ratios for low cardiorespiratory fitness stratified by CRP (upper panel) or RDW categories (lower panel). The adjusted estimates were derived from multivariate logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age, gender, race, hypertension, diabetes, body mass index, hyperlipidemia, glomerular filtration rate, serum hemoglobin and serum ferritin concentration. The lowest category namely CRP < 0.5 mg/dL and RDW < 13% served as reference categories for respective comparisons.

3.2. RDW and cardiorespiratory fitness

Table 4 demonstrates the proportion of subjects with elevated RDW (≥13%) stratified by various clinical and demographic characteristics. The prevalence (SE) of elevated RDW was 20.4 (1.0)% in the low-fitness group as compared to 14.0 (0.6)% in the control population (p < −0.001). Similar to the CRP comparison, we observed that females had a significantly higher prevalence of elevated RDW than males (p < 0.001 for both low-fitness and control groups). A significantly higher prevalence of elevated RDW in the low-fitness group was encountered in several strata including whites, blacks, hypertensive subjects as well as overweight (BMI 25–30 kg/m2) and obese subjects (BMI ≥ 30 kg/m2).

Table 4.

Proportion of subjects with high RDW (≥13%) between the study groups.

| Low fitness (n = 2394) | Controls (n = 5930) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort | 20.4 (1.0) | 14.0 (0.6) | <0.001 |

| Males | 13.4 (1.4) | 12.2 (0.8) | 0.4 |

| Females | 26.9 (1.6) | 16.2 (1.1) | <0.001 |

| Race | |||

| Whites | 15.2 (1.0) | 10.9 (1.3) | 0.03 |

| Blacks | 35.8 (1.6) | 32.4 (1.8) | 0.01 |

| Mexican-Americans | 18.5 (1.5) | 16.5 (1.8) | 0.9 |

| Others | 28.8 (7.2) | 15.3 (5.3) | 0.1 |

| Co-morbidities | |||

| Hypertension | 34.2 (3.0) | 16.8 (2.6) | 0.02 |

| Hyperlipidemia | 14.8 (3.1) | 15.8 (2.8) | 0.7 |

| BMI categories | |||

| <25 kg/m2 | 15.1 (1.6) | 12.3 (0.7) | 0.1 |

| 25–30 kg/m2 | 12.6 (2.4) | 12.1 (1.0) | 0.002 |

| ≥30 kg/m2 | 37.0 (2.3) | 29.3 (1.6) | 0.04 |

| Chronic Kidney Disease (GFR < 60 mL/min/1.73 m2) | 23.5 (5.3) | 16.7 (3.4) | 0.4 |

| Smoking status | |||

| Never-smoker | 21.7 (2.9) | 14.0 (1.0) | 0.006 |

| Former-smoker | 37.2 (1.8) | 11.3 (2.5) | <0.001 |

| Active-smoker | 21.5 (2.4) | 15.1 (1.2) | 0.03 |

Using multivariate logistic regression analysis, we demonstrated that subjects with elevated RDW had significantly higher odds for low cardiorespiratory fitness than subjects with normal RDW. Subjects with RDW of 13–16% had 1.5 times (95% CI: 1.1–2.0) higher odds of low cardiorespiratory fitness as compared to subjects with RDW < 13%. Similarly, subjects with RDW ≥ 16% had 4.0 times (95% CI: 1.9–8.6) higher odds of low cardiorespiratory fitness as compared to subjects with RDW < 13%.

3.3. Interplay of RDW and CRP

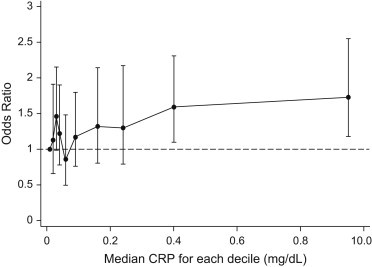

Fig. 2 demonstrates the relationship between RDW and CRP after adjusting for demographic and clinical characteristics. The figure clearly demonstrates a significant increase in the proportion of patients with elevated RDW in the two highest deciles of serum CRP concentrations (CRP > 0.3 mg/dL). Using multivariate logistic regression analysis, we studied the confounding effect of CRP upon the relationship between low cardiorespiratory fitness and elevated RDW. After adjusting for the effects of elevated CRP, a significant independent association between low cardiorespiratory fitness and elevated RDW was observed [OR (95% CI): 1.4 (1.1–1.7)]. In this adjusted multivariate model, the independent association between CRP (as a continuous variable) and low cardiorespiratory fitness was also statistically significant [OR (95% CI): 1.2 (1.02–1.4)].

Fig. 2.

Relationship between RDW and CRP after adjusting for clinical and demographic characteristics. The entire spectrum of CRP values was divided into ten equal deciles and the median of each decile is represented on the X-axis. The Y-axis represents the odds ratio of an elevated RDW (≥ 13%) in each respective CRP decile, using the first decile (CRP: 0.01 mg/dL) as reference.

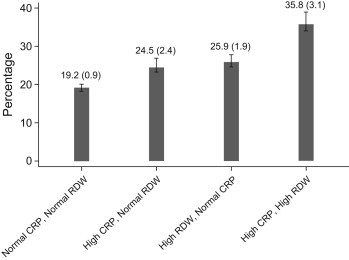

Fig. 3 demonstrates the prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness among groups constructed using CRP and RDW categories. The prevalence (SE) of low cardiorespiratory fitness among subjects with normal CRP and normal RDW was estimated as 19.2 (0.9)%. The prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness among subjects with high CRP with normal RDW and subjects with high CRP with normal RDW was estimated as 24.5 (2.4)% and 25.9 (1.9)% respectively. Although both these values were significantly higher than the reference group (normal CRP, normal RDW) (p < 0.01 for both comparisons), there was no significant difference in the prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness between these groups (p = 0.3). The prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness among subjects with high CRP and high RDW was estimated as 35.8 (3.1)%, which was significantly higher than all other CRP and RDW categories (p < 0.001 for all comparisons).

Fig. 3.

Bar graph demonstrating the prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness among sub-groups constructed using RDW and CRP categories. For each category, the prevalence is expressed as percentage (standard error).

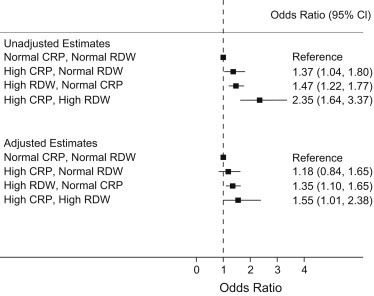

Fig. 4 demonstrates adjusted odds ratios (OR) for low cardiorespiratory fitness derived from multivariate logistic regression analysis after adjusting for demographic, clinical and laboratory parameters including serum hemoglobin and serum ferritin concentration. In comparison to subjects with normal CRP and normal RDW, a significantly higher adjusted odds of low cardiorespiratory fitness was observed among subjects with high RDW with normal CRP [OR (95% CI): 1.4 (1.1–1.7)] and subjects with high RDW with high CRP [OR (95% CI): 1.6 (1.01–2.4)].

Fig. 4.

Unadjusted (upper panel) and adjusted (lower panel) odds ratios for low cardiorespiratory fitness among sub-groups constructed using RDW and CRP categories. The adjusted estimates were derived from multivariate logistic regression analysis after adjusting for age, gender, race, hypertension, diabetes, body mass index, hyperlipidemia, glomerular filtration rate, serum hemoglobin and serum ferritin concentration. Subjects with normal CRP and normal RDW served as the reference category for this comparison.

4. Discussion

This study aimed to elucidate the relationship between low cardiorespiratory fitness with elevated RDW and/or elevated CRP. In this large dataset representative of the general US population, we observed a significant association between elevated RDW (>13%) with low cardiorespiratory fitness. In addition, we demonstrated a significantly higher prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness among subjects with elevated CRP. Both these associations demonstrated a dose–response relationship with increasing prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness with higher CRP or higher RDW values. In addition, we observed that subjects with elevated RDW and elevated CRP had much higher odds of low cardiorespiratory fitness, in comparison to those with elevation of only CRP or RDW. Furthermore, gender-based differences were evident in our study between the studied associations. Females with a low cardiorespiratory fitness had significantly higher prevalence of elevated CRP and elevated RDW, in comparison to the corresponding male cohort.

The association between elevated RDW and cardiovascular morbidity was first reported in symptomatic chronic heart failure patients.23 Subsequently, multiple studies elucidating the association between elevated RDW in several other cardiovascular settings including stable coronary artery disease and acute coronary syndromes.11–13 Several studies have demonstrated that association of RDW with all-cause mortality may be independent of anemia status, especially in the decompensated heart failure settings.10,24–26 This may indicate that elevation of RDW may precede the development of anemia in patients with chronic heart failure.

RDW is a numerical measure of the variability in the size of circulating red blood cells. High RDW, referred to as anisocytosis, reflects a greater heterogeneity in the erythrocyte size, which is caused by disturbances in erythrocyte maturation and degradation.12,27 Although the exact pathophysiologic mechanisms explaining the association between elevated RDW and adverse cardiovascular outcomes are not well understood, several studies have proposed that elevated RDW may reflect an underlying pro-inflammatory state,13 which has been shown to be associated with adverse outcomes.28 It has been demonstrated that a chronic inflammatory state may contribute to ineffective erythropoiesis causing immature erythrocytes to enter the circulation, resulting in elevated RDW. Several mechanisms are believed to mediate the relationship between the chronic inflammatory state and ineffective erythropoiesis leading to elevated RDW. Inflammatory markers like tumor necrosis factor-α and interleukin-6 may hinder erythropoiesis via direct suppression of erythroid precursors, promotion of apoptosis of precursor cells, enhancement of erythropoietin resistance in the precursor cell lines and reduction in bioavailability of iron for hemoglobin synthesis.29,30 In addition to the chronic inflammation, higher oxidative stress may be another potential mechanism linking elevated RDW and adverse cardiovascular outcomes. Higher oxidative stress may lead to reduced erythrocyte survival and thus may result in anisocytosis due to an increase in the proportion of circulating premature erythrocytes. The association of elevated RDW with higher oxidative stress and chronic subclinical inflammation hints toward a close association with adverse cardiovascular outcomes since both of these underlying pathobiological processes have been shown to predict outcomes in cardiovascular disease.6,7,12

Over the past few decades, cardiorespiratory fitness has emerged as one of the strongest predictors of morbidity and mortality arising as a result of cardiovascular disease in subjects with or without heart disease at baseline. Several studies have demonstrated a dose-dependent inverse relationship between cardiovascular mortality and cardiorespiratory fitness.2–5 Differences in cardiorespiratory fitness have been demonstrated to be associated with considerable changes in the lifetime risks for cardiovascular-related mortality at each index age.3 For example, a 65-year-old individual with a low cardiorespiratory fitness level would be predicted to have a 35.6% risk of lifetime cardiovascular-related mortality versus a 17.1% risk of death due to heart disease if he/she had a moderate or high level of fitness. Berry et al have demonstrated that a single measurement of low physical fitness in the midlife translates into a 15–20% absolute increase in the lifetime risk of cardiovascular-related mortality.3 In addition, not only is cardiorespiratory fitness a predictor for cardiovascular-related morbidity and mortality, but also fitness represents an established treatment target which may help improve multiple clinically relevant risk reduction metrics.

Although several studies have elucidated the role of RDW and inflammation upon adverse clinical outcomes in established heart disease, the temporal relationship of these biomarkers with cardiovascular disease is not well understood. By demonstrating an association of RDW and CRP with low cardiorespiratory fitness, our study helps establish several facts. First, the abnormalities in RDW and CRP that have seemed to be associated with adverse cardiovascular outcomes may precede the onset of heart disease by several decades. Our study demonstrates that young subjects devoid of physical limitations or cardiopulmonary ailments with a low exercise capacity are likely to possess a chronic inflammatory milieu and a high oxidative stress, which may predispose these individuals to cardiovascular disease in later life. Secondly, our study helps establish the link between the strong association between low cardiorespiratory fitness and an adverse cardiovascular outcome in later life that has been demonstrated in several studies including the Lipid Research Clinics,4 Veterans Affairs Study31 and Cooper Center Longitudinal Study.3 We have demonstrated that subjects with low cardiorespiratory fitness have elevated RDW by virtue of chronic inflammation and high oxidative stress, which is likely to promote atherosclerosis and lead to cardiovascular disease. Furthermore, we have demonstrated that presence of elevated RDW along with elevated CRP has a higher likelihood of being associated with low cardiorespiratory fitness than elevated CRP or elevated RDW alone.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Our study is a cross-sectional study and suffers from traditional biases of this study design. Although it is difficult to establish, our study helps clarify that elevation of RDW and CRP precedes the development of cardiovascular disease by several decades. The results of this study certainly lead to strong, albeit indirect conclusions, which help further our understanding about the roles of inflammation and oxidative stress in the genesis of cardiovascular disease. We derived our data from a large well-validated and heterogeneous dataset, which is representative of the general US population. The cardiorespiratory fitness testing was performed using a robust well-validated protocol, thereby, reducing the biases arising from inaccurate testing.

5. Conclusions

In this large representative dataset of the non-institutionalized general US population, we observed a significant association between elevated RDW and elevated CRP with low cardiorespiratory fitness. Both these associations demonstrated a dose–response relationship with increasing prevalence of low cardiorespiratory fitness with higher CRP or higher RDW values. In addition, we observed that subjects with elevated RDW and elevated CRP had much higher odds of low cardiorespiratory fitness, in comparison to those with elevation of only CRP or RDW. Furthermore, females with a low cardiorespiratory fitness had a significantly higher prevalence of elevated CRP and elevated RDW, in comparison to the corresponding male cohort.

Conflicts of interest

The author has none to declare.

References

- 1.Roger V.L., Go A.S., Lloyd-Jones D.M. Heart disease and stroke statistics–2011 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:e18–e209. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182009701. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Blair S.N., Kohl H.W., 3rd, Barlow C.E. Changes in physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy and unhealthy men. JAMA. 1995;273:1093–1098. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Berry J.D., Willis B., Gupta S. Lifetime risks for cardiovascular disease mortality by cardiorespiratory fitness levels measured at ages 45, 55, and 65 years in men. The Cooper Center Longitudinal Study. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2011;57:1604–1610. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2010.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ekelund L.G., Haskell W.L., Johnson J.L. Physical fitness as a predictor of cardiovascular mortality in asymptomatic North American men. The Lipid Research Clinics Mortality Follow-up Study. N Engl J Med. 1988;319:1379–1384. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198811243192104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kodama S., Saito K., Tanaka S. Cardiorespiratory fitness as a quantitative predictor of all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events in healthy men and women: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2009;301:2024–2035. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ridker P.M., Cushman M., Stampfer M.J., Tracy R.P., Hennekens C.H. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:973–979. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199704033361401. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Libby P., Ridker P.M., Maseri A. Inflammation and atherosclerosis. Circulation. 2002;105:1135–1143. doi: 10.1161/hc0902.104353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Danesh J., Wheeler J.G., Hirschfield G.M. C-reactive protein and other circulating markers of inflammation in the prediction of coronary heart disease. N Engl J Med. 2004;350:1387–1397. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa032804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Berliner J.A., Navab M., Fogelman A.M. Atherosclerosis: basic mechanisms. Oxidation, inflammation, and genetics. Circulation. 1995;91:2488–2496. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.91.9.2488. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.van Kimmenade R.R., Mohammed A.A., Uthamalingam S., van der Meer P., Felker G.M., Januzzi J.L., Jr. Red blood cell distribution width and 1-year mortality in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2010;12:129–136. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Dabbah S., Hammerman H., Markiewicz W., Aronson D. Relation between red cell distribution width and clinical outcomes after acute myocardial infarction. Am J Cardiol. 2010;105:312–317. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2009.09.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Patel K.V., Ferrucci L., Ershler W.B., Longo D.L., Guralnik J.M. Red blood cell distribution width and the risk of death in middle-aged and older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2009;169:515–523. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2009.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tonelli M., Sacks F., Arnold M., for the Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) Trial Investigators Relation between red blood cell distribution width and cardiovascular event rate in people with coronary disease. Circulation. 2008;117:163–168. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.727545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ghaffari S. Oxidative stress in the regulation of normal and neoplastic hematopoiesis. Antioxid Redox Signal. 2008;10:1923–1940. doi: 10.1089/ars.2008.2142. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhanes/nhanes_questionnaires.htm; Accessed 22.12.11.

- 16.American College of Sports Medicine . 6th ed. Lippincott Williams and Wilkins Company; Philadelphia, PA: 1995. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Blair S.N., Kohl H.W., 3rd, Paffenbarger R.S., Jr. Physical fitness and all-cause mortality. A prospective study of healthy men and women. JAMA. 1989;262:2395–2401. doi: 10.1001/jama.262.17.2395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cureton K.J., Warren G.L. Criterion-referenced standards for youth health-related fitness tests: a tutorial. Res Q Exerc Sport. 1990;6:7–19. doi: 10.1080/02701367.1990.10607473. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cureton KJ, Plowman SA. Aerobic capacity assessments. In: Welk GJ, Morrow JR Jr, Falls HB, eds. Fitnessgram Reference Guide. Dallas, TX: Cooper Institute. http://dev.cooperinst.org/shopping/PDF%20format/Fitnessgram%20Reference%20Guide.pdf; Accessed 16.01.12.

- 20.Levey A.S., Coresh J., Balk E. National Kidney Foundation practice guidelines for chronic kidney disease: evaluation classification and stratification. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139:137–147. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-139-2-200307150-00013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coresh J., Selvin E., Stevens L.A. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298:2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selvin S., Manzi J., Stevens L.A. Calibration of serum creatinine in the National Health and Nutrition Examination Surveys (NHANES) 1988–1994, 1999–2004. Am J Kidney Dis. 2007;50:918–926. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2007.08.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Felker G.M., Allen L.A., Pocock S.J., CHARM investigators Red cell distribution width as a novel prognostic marker in heart failure: data from the CHARM Program and the Duke Databank. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2007;50:40–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2007.02.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Zalawadiya S.K., Zmily H., Farah J., Daifallah S., Ali O., Ghali J.K. Red cell distribution width and mortality in predominantly African-American population with decompensated heart failure. J Card Fail. 2011;17:292–298. doi: 10.1016/j.cardfail.2010.11.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pascual-Figal D.A., Bonaque J.C., Redondo B. Red blood cell distribution width predicts long-term outcome regardless of anaemia status in acute heart failure patients. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:840–846. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp109. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jackson C.E., Dalzell J.R., Bezlyak V. Red cell distribution width has incremental prognostic value to B-type natriuretic peptide in acute heart failure. Eur J Heart Fail. 2009;11:1152–1154. doi: 10.1093/eurjhf/hfp157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Perkins S.L. 11th ed. Lippincott Wilkins & Williams; Salt Lake City: 2003. Examination of Blood and Bone Marrow. Wintrobe's Clinical Hematology. 5–25. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tsimikas S., Willerson J.T., Ridker P.M. C-reactive protein and other emerging blood biomarkers to optimize risk stratification of vulnerable patients. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2006;47:C19–C31. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2005.10.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ghali J.K. Anemia and heart failure. Curr Opin Cardiol. 2009;24:172–178. doi: 10.1097/HCO.0b013e328324ecec. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ridker P.M., Rifai N., Pfeffer M.A. Inflammation, pravastatin, and the risk of coronary events after myocardial infarction in patients with average cholesterol levels. Cholesterol and Recurrent Events (CARE) Investigators. Circulation. 1998;98:839–844. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.98.9.839. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Myers J., Prakash M., Froelicher V., Do D., Partington S., Atwood J.E. Exercise capacity and mortality among men referred for exercise testing. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:793–801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa011858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]