Abstract

The prevailing otolaryngologic approach to treatment of age-related hearing loss (ARHL), presbycusis, emphasizes compensation of peripheral functional deficits (i.e., hearing aids and cochlear implants). This approach does not address adequately the needs of the geriatric population, one in five of whom is expected to consist of the “old old” in the coming decades. Aging affects both the peripheral and central auditory systems, and disorders of executive function become more prevalent with advancing age. Growing evidence supports an association between age-related hearing loss and cognitive decline. Thus, to facilitate optimal functional capacity in our geriatric patients, a more comprehensive management strategy of ARHL is needed. Diagnostic evaluation should go beyond standard audiometric testing and include measures of central auditory function including dichotic tasks and speech-in-noise testing. Treatment should include not only appropriate means of peripheral compensation, but also auditory rehabilitative training and counseling.

In 2008 the United States Census Bureau projected that the US population aged 65 and older will grow from 40.2 million in 2010 (13.5% of the population) to 88.5 million in 2050 (20.5%). The Federal Interagency Forum on Aging-Related Statistics estimates that one fifth of this 20% will be in those 85 and older. Studies based on National Health and Nutritional Examination Survey (NHANES) show that an increasing proportion of the population suffers from age-related hearing loss (ARHL) reaching over 80% of those over 85 years of age1. It is well recognized that ARHL, presbycusis, is multifactorial and influenced by genetics (up to 50% have significant family history), cardiovascular health (in turn influenced by smoking and diabetes), history of noise exposure, as well as, ototoxic exposures and otologic disorders. Management of ARHL typically focuses on hearing aids or cochlear implants. This strategy aimed at compensating for peripheral losses does not yield adequate benefit in many geriatric patients. In this large proportion of our patients, the complaint of “I can hear, but can’t understand” persists despite adequate amplification. What are we missing? At the 2012 annual meeting of American Academy of Otolaryngology – Head & Neck Surgery (AAO-HNS), a miniseminar, co-sponsored by the Hearing and Geriatric Committees of the AAO-HNS, was held to explore the answers.

A common complaint of older listeners is “I have difficulty understanding speech when it is noisy, but I do all right in quiet”. The prevailing assumption has been that most of the problem is peripheral (ie, cochlear). Recent evidence2 is not compatible with that assumption. Auditory performance in the geriatric patient can be influenced by decreased spiral ganglion cells, decreased central plasticity, central auditory processing disorder, increased incidence of central nervous system disease, and cognitive decline among other factors. Comprehensive management and rehabilitation of ARHL will likely require strategies to address all of these factors.

Toward the goal of comprehensive management, an important question to consider is not only, ‘what can the geriatric patient teach us about aural rehabilitation?’ but also ‘what can aural rehabilitation teach us about the geriatric patient?” A glimpse at the answers may lie within what is already known about cochlear implantation. Cochlear implants have been studied extensively in the geriatric population, and provide patients with severe to profound hearing loss with substantial and incontrovertible benefit compared with hearing aids. Many studies show that the benefit for older individuals (variably defined, but generally older than 65) is comparable to that for younger matched adult controls.

However, the studies that show subtle but significant differences are worthy of closer examination as they may provide insight into the physiology of normal aging. First, some studies show that performance is in fact slightly worse (but still excellent) in older individuals. Second, all geriatric implantees are not the same, and even when controlling for duration of deafness, the “old-old” cohort over age 70 may not perform as well as those under age 703. Third, the learning curve may be different for older individuals, taking years to achieve speech recognition levels reached after only 1 year by younger matched adults4. Fourth, with the addition of background noise, speech recognition may be impaired substantially in older individuals – a limitation that unlike hearing in quiet, does not improve with time5. Fifth, unlike matched adults, side may play a role in outcomes, with right side implantation resulting in improved speech perception6.

Understanding speech requires more than perception: a complex array of brain functions is involved that may be considered anatomically as involving the associative cortical areas of the brain and physiologically as executive functioning, which includes short-term memory, attention, inhibition, and decision making. A relatively simple, established method to evaluate the presence and extent of central presbycusis involves speech-in-noise tests. Examples are the Dichotic Sentence Identification (DSI) test, where bilateral competing speech inputs are involved, or the Synthetic Sentence Identification (SSI) test with the Ipsilateral Competing Message (ICM) test, in which unilateral competing speech constructs are introduced. It has been found that people with early Alzheimer’s disease—who usually have decreased executive functioning— fail these tests at the 80% correct level7. Even more revealing are the observations that people who do very poorly (<50% correct) on the SSI-ICM or DSI have a 7- to 12-fold increase in risk of receiving a diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease in the subsequent 3 to 10 years8,9.

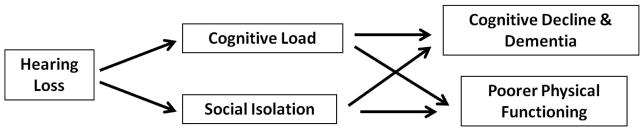

A conceptual model through which ARHL could be mechanistically associated with cognitive decline and dementia is presented in Figure 1. In this model, two non-mutually exclusive pathways of increased cognitive load and loss of social engagement mediate effects of ARHL on cognitive functioning10. Recent epidemiologic studies have begun to explore whether ARHL is associated independently with cognitive functioning and incident dementia consistent with this model. Using cross-sectional data from both the NHANS11 and the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging (BLSA)12, Lin and colleagues have demonstrated that greater hearing loss is associated with poorer cognitive functioning on non-verbal tests of memory and executive function among older adults. In both of these studies, a 25-dB shift in the speech-frequency pure tone average in older adults was associated with effects on cognitive test scores equivalent to 7 years of aging. Analysis of longitudinal cognitive data from the Health Aging and Body Composition Study demonstrated similar findings13. Compared to those with normal hearing, those individuals with hearing loss had accelerated rates of decline on non-verbal cognitive tests. Finally, analysis of longitudinal data from a cohort of older adults in the BLSA demonstrated that compared to those individuals with normal hearing, those with a mild, moderate, and severe hearing loss had a two, three, and five-fold increased risk of incident dementia, respectively10.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model of the association of hearing loss with cognitive and physical functioning in older adults.

Research demonstrating that ARHL is associated independently with cognitive functioning and dementia is intriguing because the hypothesized mechanistic pathways (Figure 1) may be amenable in part to hearing rehabilitative therapies. A key aspect of hearing loss treatment that needs to be emphasized, though, is that comprehensive hearing loss treatment does not consist simply of fitting a hearing aid or cochlear implant.

In the non-geriatic population, it is generally held (and strongly supported) that binaural amplification (hearing aids, cochlear implants, or bi-modal) is preferential to unilateral amplification. However, the opposite may be true in the geriatric patient. Some patients with central auditory processing disorder perform better with a single hearing aid in the better ear than with binaural aids14. In noise, 71% of geriatric patients perform better with one hearing aid, rather than two15. This might be due to an imbalance or asynchrony in binaural signal, or a cognitive processing deficit – and serves to highlight the importance of dichotic tests when evaluating any older patient with hearing loss.

Ultimately, issues of aural rehabilitation reach far beyond peripheral speech recognition and involve larger and more complex issues of communication, quality of life, mood, cognition, and overall health. The goal of hearing loss treatment is to ensure that the patient can communicate effectively in all settings. A comprehensive approach entails appropriate diagnostics that involves dichotic tasks and speech-in-noise testing, as well as, proper amplification with individualized consideration of binaural vs. monoaural amplification/implantation and rehabilitative counseling and training. Since the relationship between ARHL and cognitive decline is of vital interest to the otolaryngologist, we need to define our role in initiating cognitive evaluation by either integrating relevant assessments into our office evaluation or making appropriate referrals (e.g., neurology/neuropsychology). To reach these goals, considerably more research is necessary in the emerging field of auditory neurotology. For example, universally accepted, valid, normative data for adults are needed to establish central auditory screening tests that can be performed efficiently. Randomized controlled trials are needed to investigate the critical questions of whether treating hearing loss could delay cognitive decline or whether monoaural amplification/implantation is more advantageous than binaural devices for some geriatric patients with hearing loss and early cognitive decline or central processing disorder. Global understanding of the hearing process is essential for optimal care of ARHL; and otolaryngologists should not only be familiar with the multidisciplinary information on this complex subject but should be leaders in research into the entire auditory pathway and its clinical rehabilitation.

References

- 1.Lin FR, Thorpe R, Gordon-Salant S, Ferucci L. Hearing loss prevalence and risk factors among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66A:582–590. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gates GA, Gibbons LE, McCurry SM, et al. Executive dysfunction and presbycusis in older persons with and without memory loss and dementia. Cogn Behav Neurol. 2010;23:218–223. doi: 10.1097/WNN.0b013e3181d748d7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin FR, Chien WW, Li L, Clarrett DM, Niparko JK, Francis HW. Cochlear implantation in older adults. Medicine. 2012;91:229–241. doi: 10.1097/MD.0b013e31826b145a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Herzog M, Schön F, Müller J, Knaus C, Scholtz L, Helms J. Long term results after cochlear implantation in elderly patients. Laryngorhinootologie. 2003;82:490–493. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40896. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lenarz M, Sönmez H, Joseph G, Büchner A, Lenarz T. Cochlear implant performance in geriatric patients. Laryngoscope. 2012;122:1361–1365. doi: 10.1002/lary.23232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Budenz CL, Cosetti MK, Coelho DH, Birenbaum B, Babb J, Waltzman SB, Roehm PC. The effects of cochlear implantation on speech perception in older adults. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2011;59:446–453. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2010.03310.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Gates GA, Karzon RK, Garcia P, et al. Auditory dysfunction in aging and senile dementia of the Alzheimer’s type. Arch Neurol. 1995;52:626–634. doi: 10.1001/archneur.1995.00540300108020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gates GA, Beiser A, Rees TS, D’Agostino RB, Wolf PA. Central auditory dysfunction may precede the onset of clinical dementia in people with probable Alzheimer’s disease. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2002;50:482–488. doi: 10.1046/j.1532-5415.2002.50114.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gates GA, Anderson ML, McCurry SM, Feeney MP, Larson EB. Central auditory dysfunction as a harbinger of Alzheimer dementia. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;137:390–395. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2011.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lin FR, Metter EJ, O’Brien RJ, Resnick SM, Zonderman AB, Ferrucci L. Hearing loss and incident dementia. Arch Neurol. 2011;68:214–220. doi: 10.1001/archneurol.2010.362. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lin FR. Hearing loss and cognition among older adults in the United States. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2011;66:1131–1136. doi: 10.1093/gerona/glr115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lin FR, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ, An Y, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Hearing loss and cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychol. 2011;25:763–770. doi: 10.1037/a0024238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lin FR, Yaffe K, Xia J, et al. Hearing loss and cognitive decline among older adults. Arch Intern Med. 2012 doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.1868. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chmiel R, Jerger J. Hearing aid use, central auditory disorder, and hearing handicap in elderly persons. J Am Acad Audiol. 1996;7:190–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Henkin Y, Waldman A, Kishon-Rabin L. The benefits of bilateral versus unilateral amplification for the elderly: are two always better than one? J Basic Clin Physiol Pharmacol. 2007;18:201–16. doi: 10.1515/jbcpp.2007.18.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]