Abstract

To identify recent studies in the scientific literature that evaluated structured postgraduate public health and biomedical training programs and reported career outcomes among individual trainees. A comprehensive search of several databases was conducted to identify published studies in English between January 1995–January 2012 that evaluated career outcomes for trainees completing full-time public health or biomedical training programs of at least 12 months duration, with structured training offered on-site. Of the over 600 articles identified, only 13 met the inclusion criteria. Six studies evaluated U.S. federal agency programs and six were of university-based programs. Seven programs were solely or predominantly of physicians, with only one consisting mainly of PhDs. Most studies used a cohort or cross-sectional design. The studies were mainly descriptive, with only four containing statistical data. Type of employment was the most common outcome measure (n=12) and number of scientific publications (n=6) was second. The lack of outcomes evaluation data from postgraduate public health and biomedical training programs in the published literature is a lost opportunity for understanding the career paths of trainees and the potential impact of training programs. Suggestions for increasing interest in conducting and reporting evaluation studies of these structured postgraduate training programs are provided.

Introduction

One of the major roles of educational and research institutions is training the next generation of scientists and practitioners [10, 11, 13, 15, 18, 23, 35]. There are an estimated 37,000–68,000 persons with PhDs and 5,000 physicians in postdoctoral training positions in the United States [7]. Given the size and scope of the postgraduate public health and biomedical workforce training enterprise, one might expect reports of evaluating career outcomes of individuals who complete these training programs to be plentiful in the published literature. On occasion, institutions and foundations that support individual fellowships, such as career development awards, conduct and publish career outcome evaluations of awardees [14, 21, 32]. These evaluations include awardees across multiple institutions and the career development training, being individualized, is highly variable across awards. This is in contrast to evaluation of structured, postgraduate training programs offered on-site to a cadre of trainees. Evaluations of these structured programs in the literature are rare and predominantly limited to medical students and physicians [3, [8, [27, [28].

As an example, in a comprehensive literature review of studies from 1966–2006 reporting relationships between career development (broadly defined) and mentoring programs in medicine, Sambunjak and colleagues found only 39 evaluation studies, 34 (87%) of which used a cross-sectional design [28]. A review conducted by Buddeberg-Fischer of the literature from 1966 to 2002 identified only 16 evaluation studies of mentoring programs in medicine, and found most lacked structure (i.e., a defined curriculum) and included no defined short-term or long-term outcome measures [3]. In addition, most studies included in these two reviews had weak evaluation research designs [33], including small samples sizes, no comparison populations, and use of self-reported data collected through one-time cross-sectional surveys of program graduates with the emphasis largely on measures of satisfaction with the program rather objective career outcomes [3, 27, 28]. Of particular concern with the cross-sectional design, is that this captures only one point in time with no ability to follow accomplishments over a longer period.

The number and quality of studies focused on postgraduate training programs in the public health and biomedical disciplines represent a major lost opportunity. This lack of easily accessible evaluation data has become increasingly visible with national efforts to evaluate the biomedical workforce and postdoctoral experience [7, 30, 31]. A recent report on the future of the biomedical workforce from an Advisory Committee to the National Institutes of Health (NIH) Director highlighted the lack of data as one of the impediments to projecting career paths for postdoctoral scholars [7]. Partially in response to this, members of the committee issued a recommendation to evaluate training programs supported by the NIH and report these results so prospective trainees could have access to outcomes data.

With the broad and evolving changes in biomedical and public health research and practice, a constrained funding environment, and growing calls for accountability [4, 7], this presents a good opportunity to examine the recent literature focused specifically on evaluating individual-level career outcomes of participants in postgraduate public health and biomedical training programs with structured training provided on-site at the trainee's home institution and to provide a framework for future evaluations of these programs. Herein, the results from a comprehensive literature review of postgraduate public health and biomedical training programs outcome evaluations published from 1995–2012 are presented. The focus of this literature review was studies of full-time structured programs conducted within a given institution and reporting career outcomes of trainees. A secondary purpose of this report is to provide specific recommendations on how public health and biomedical training programs can take steps to improve or expand their evaluation efforts and the benefits likely to accrue from doing so.

Methods

The focus of this literature review was outcomes studies of full-time postgraduate structured public health and biomedical training programs (e.g. postgraduate programs in epidemiology, biostatistics, basic/laboratory science related to health, medical fellowships, nursing, health policy, or social and behavioral science related to health) with structured training provided on-site at the home institution. Only studies with career-oriented outcome data were considered, e.g., scientific publications, type of employment, career advancement, or receipt of grants. To help differentiate career-oriented from short-term training programs, participants had to be full-time postgraduate trainees (i.e., performing at least 40 hours of work per week) in a structured program of at least 12 months duration. Studies by institutions or foundations awarding individual fellowships were excluded because trainees work in a multitude of academic institutions with highly variable program structures and training experiences and often with no specific or defined curriculum across awardees. Studies based solely on graduate students, such as those of medical students, were excluded. In addition, evaluations of skills-based or similar training programs with outcomes, e.g., communication or surgical techniques, were excluded because they were short-term in nature without career outcomes.

The authors worked closely with an experienced biomedical librarian/informationist at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) to select search terms and databases. Because there is no standard search strategy to identify published studies about postgraduate public health and biomedical training programs, the following search terms were utilized to search MEDLINE databases:

Search Strategy 1 - (“Evaluation Studies as Topic”[Mesh] OR “Evaluation Studies”[Publication Type] OR “Program Evaluation”[Mesh] OR “Data Collection”[Mesh]) AND (“Fellowships and Scholarships”[Majr] OR internship, nonmedical[majr] OR fellowship*[ti] OR mentor*[ti] OR preceptorship*[ti])

OR

Search Strategy 2 - (“Career Mobility”[Mesh] OR “Career Choice”[Mesh] OR “Job Satisfaction”[Mesh] OR “Professional Competence”[Mesh]) AND (“Fellowships and Scholarships”[Majr] OR internship, nonmedical[majr] OR fellowship*[ti] OR mentor*[ti] OR preceptorship*[ti]).

Similar strategies were used to identify English language articles describing evaluations of biomedical and public health-related training programs published between January 1, 1995 and January 31, 2012 from the following resources: Scopus, Web of Science, ERIC (Educational Resource Information Center) and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) databases, as well as the LexisNexis business and news databases. Using the search strategies above, 598 articles of interest were identified.

Two junior members of the research team (A.K. and E.N.) received extensive training on the inclusion and exclusion criteria (Table 1) for this literature review from the senior authors (J. F-B. and D.N), which included reviewing a test set of articles. Each of the junior members independently reviewed and coded half of the initial 598 articles. They then switched lists to determine if there was concurrence on articles to include. Articles identified for potential inclusion were provided to the senior members of the research team, who reviewed them independently of each other. Any disagreements about which articles to include were quickly resolved based on discussions between the senior authors. A total of 7 articles met the above inclusion criteria. The reference lists from each of these articles was then systematically reviewed, which successfully identified 6 additional articles, for an overall total of 13 articles.

Table 1.

Exclusion and Inclusion Criteria for Articles in Postgraduate Public Health and Biomedical Training Program Literature Review

| Article EXCLUDED if met ONE of the following conditions: | Article INCLUDED if contained ALL of the following conditions: | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Majority of population were faculty members, graduate and medical school students, participants whose appointment is not a full-time (i.e. 40+ hours/week) training position, participants in part-time training programs | Postgraduate trainees in full-time (i.e. 40+ hours/week) research or health practice training programs |

| Duration | Programs completed in <12 months | Programs requiring 12+ months for completion |

| Location | Trainees in multiple sites (e.g. grantees located at various institutions with variable training program structures and experiences) | Structured training program provided on-site to a cadre of trainees |

| Outcome | Only satisfaction measures without also including career outcomes or skills-based outcomes (e.g. surgical techniques or communication) | Contained at least one career outcome, such as: current employment information or information on employment immediately following participation in training program, publication counts, grant funding, etc. |

The senior authors then systematically abstracted information from each article, which included descriptions about the training program, demographic data on participants, years evaluated, study design, outcome measure(s), data source(s), presence of a comparison population, and inclusion of statistical testing results. Sources of evaluation data were classified as survey or archival; archival sources included program or other organization-specific databases (e.g., spreadsheets maintained by staff), scientific publication databases (e.g., PubMed), grants databases, or curriculum vita.

Results

Brief descriptions of the characteristics of each training program and their participants are provided in Table 2. Ten studies were of programs in the United States [6, 8, 12, 16, 17, 24, 25, 34, 36, 37], and most were at least two years in length [2, 6, 8, 12, 17, 19, 20, 25, 34, 36, 37]. Six were evaluations of federal government-affiliated programs [2, 8, 12, 19, 20, 36], six were university-based [6, 17, 24, 25, 34, 37], and one had another affiliation [16]. The time period for examining career outcomes ranged from one year in several studies to up to 50 years.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Postgraduate Health Training Programs

| Source | Program Description and Objectives | Program Duration | Study Time Frame | Participants |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betts, 1998 | Foreign Epidemiology Training Program in Mexico, Thailand, Philippines, Spain, and Uganda that provides applied epidemiology training for health professionals. | 2 years | 1980–1998a | 136 postgraduate trainees (95% physicians) |

| Simon, 1999 | Research-intensive fellowship at Harvard University designed to increase medical school faculty trained in general internal medicine. | 2 years | 1979–1997 | 103 physicians |

| Thacker, 2001 | Epidemic Intelligence Service (EIS) fellowship training program in applied epidemiology for health professionals through the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. | 2 years | 1951–2000 | 2,338 postgraduate trainees (78% physicians) |

| Waterbor, 2002 | Fellowship in cancer prevention and control for pre-and post-doctoral students at the University of Alabama-Birmingham School of Public Health. | 2–3 years | 1988–2001 | 39 pre- and post-doctoral trainees (80% pre-doctoral trainees) |

| Dores, 2006 | Postdoctoral fellowship program in cancer prevention research and leadership at the U.S. National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health. | 2–3 years | 1987–1997 | 64 postdoctoral trainees (71% PhDs) |

| Gordon, 2007 | Postdoctoral clinical research fellowship program at the U.S. National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial Research, National Institutes of Health. | 1–3 years | 2000–2005 | 11 postdoctoral trainees (82% dentists) |

| Jones, 2007 | Postgraduate fellowship program in health policy in Washington DC area. | 1 year | 1987–2005 | 18 postgraduate trainees with varied backgrounds |

| Landrigan, 2007 | Fellowship at five U.S. research institutions to train pediatricians to become physician-scientists and academic leaders in pediatric environmental health. | 3 years | 2001–2007 | 13 physicians |

| Lopez, 2008 | Foreign Epidemiology Training Program in Costa Rica, El Salvador, Guatemala, Honduras, Nicaragua, Panama, and the Dominican Republic that provides applied epidemiology training for health professionals. | 2 years | 2000–2007a | 58 postgraduate trainees (disciplines NA) |

| Cronholm, 2009 | Fellowship for family physicians at University of Pennsylvania designed to enhance research training and academic career development. | 2–3 years | 1997–2007 | 15 physicians |

| Rivera, 2010 | Fellowship in clinical nutrition education for physicians at the Cleveland Clinic. | 1 year | 1994-NA | 14 physicians |

| Rose, 2011 | Fellowship at the Mayo Clinic (MN) designed to train physicians in anesthesiology critical care medicine. | 2–3 years | 2000–2010 | 28 physicians |

| Matovu, 2011 | Postgraduate fellowship training program at the Makerere University School of Public Health (Uganda) designed to build HIV/AIDS leadership and management capacity. | 2 years | 2002–2008 | 54 postgraduate trainees with varied backgrounds |

Number of years varied across countries

NA: Not available

Participants in seven studies were solely or predominately physicians [2, 6, 17, 24, 25, 34, 36], one consisted predominantly of persons with PhDs [8], with the rest having persons from a variety of disciplines or with disciplines not specified. Outcome data were available from a high percentage of program participants (range: 65–100%; data not shown in tables). Five studies [8, 12, 16, 17, 36] included current program participants in their data analyses. In terms of demographics, participants' sex was mentioned in ten studies (range: 14% to 72% female), with mean age (range: late 20s to late 30s) or race/ethnicity mentioned in six and five studies, respectively.

A summary of evaluation methods and results for each of the 13 studies is described in Table 3. Cohort or cross-sectional designs were used in ten studies [2, 8, 12, 17, 20, 24, 25, 34, 36, 37], one study used a case-control design [16], and study design information was missing for the other two. Four studies used surveys as their sole source of data [2, 16, 24, 34], four used archival sources only [8, 12, 25, 37], one used a survey and archival sources [17], and four did not describe the source(s) of data. Only the study by Jones et al contained a comparison population [16]. It is worth noting outcome data was predominantly descriptive in nature only, as only four studies contained any statistical testing results such as p-values [8, 16, 17, 34].

Table 3.

Postgraduate Training Program Evaluation Study Parameters

| Source | Study Design | Data Source | Comparison Group | Statistical Testing | Outcome Measure(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Betts, 1998 | Cross-sectional | Survey | None | No | Employment before and after completing fellowship, scientific publications, conference presentations |

| Simon, 1999 | Cross-sectional | Survey | None | Yes | Current employment (academic appointment), academic rank, teaching and mentoring, time spent in research |

| Thacker, 2001 | Cohort | NA | None | No | Current employment |

| Waterbor, 2002 | Cohort | Archival | None | No | Current employment, scientific publications, conference presentations |

| Dores, 2006 | Cohort | Archival | None | Yes | Scientific publications |

| Gordon, 2007 | Cohort | Archival | None | No | Scientific publications, current employment, involvement in research, receipt of NIH research funding |

| Jones, 2007 | Case-control | Survey | 10 unselected applicants | Yes | Employment upon completing fellowship, involvement in health policy |

| Landrigan, 2007 | Cross-sectional | Archival and Survey | None | Yes | Current employment, scientific publications, receipt of research grant funding |

| Lopez, 2008 | NA | NA | None | No | Current employment |

| Cronholm, 2009 | NA | NA | None | No | Current employment, scientific publications, receipt of research grant funding |

| Rivera, 2010 | Cross-sectional | Survey | None | No | Current employment, subsequent fellowship training, clinical nutrition practice, income |

| Rose, 2011 | Cohort | Archival | None | No | Current employment |

| Matovu, 2011 | Cohort | NA | None | No | Current employment, country of employment |

NA: Not available

Type of employment was the most common outcome measure utilized, with 12 studies having at least one measure of this type. There was wide variability, however, in the type of employment measure utilized. Studies reporting employment varied on either reporting current employment or employment immediately after completion of the program. Within these studies, some highlighted the employment sector of program graduates, e.g., government, university, another training program, or private medical practice. Others mentioned specific type of job, rank, or area of specialization, or job rank, e.g., epidemiologist, associate professor, or health policy involvement. Two studies from outside the U.S. reported data on country of employment.

The second most common outcome measure was scientific publications of program graduates, which was mentioned in six studies. Publications were categorized in different ways, such as total or average number of first-authored publications, peer-reviewed journal articles, book chapters, etc. Only two studies reported scientific conference presentations as an outcome measure. Among studies of university-based programs only, a few additional measures were used, which included receipt of grant research funding (three studies), time spent conducting research (two studies), and teaching or mentoring responsibilities (two studies).

Discussion

From the outset, this literature review of evaluation studies of postgraduate public health and biomedical training programs published in the past 17 years was designed to be exploratory in nature since the breadth or depth of research in this area was unclear, and there is no standard terminology for search terms (i.e., it is possible additional or more refined terms may have uncovered more publications). Nevertheless, despite an attempt to identify evaluations of postgraduate training programs with outcome measures from a wide variety of health fields, there is a dearth of published, easily accessible evaluation research in this area, particularly for PhD postdoctoral programs. The small number of studies we found makes comparisons across reports difficult. For example, more data is needed to compare and contrast outcomes by discipline, size of program, or duration of training. All of these factors will likely influence career outcomes.

The studies reported here were identified through a comprehensive literature review and, therefore, career outcomes data reported by training programs to funding agencies were not included. These reports are currently not publicly available but would be a plentiful source of data. Two mechanisms supporting large number of trainees with NIH funding are the T32 and R25 training grants. Principle investigators on both of these grants are required to report 10 years of data on trainees including, at a minimum, current position and source of support. This reporting requirement suggests that there is much more data available than can be found through traditional literature searches.

The studies we identified herein had at least one substantial design flaw and it is likely that these internal evaluations would be susceptible to these same issues. The most serious concern was the lack of a comparison population to assess whether outcomes were associated with participation in a training program [33]. Evaluating outcomes data captured only after the program but not before and including outcomes of current trainees in the “alumni” group were also common problems. In addition, statistical analyses were largely absent.

There are multiple explanations for the number and quality of the studies found during this literature search. Limited resources are the most likely explanation for why there are so few studies of career-oriented outcome studies of postgraduate trainees [1, 5, 7, 26]. Newer social media technologies may lower the cost of finding and contacting past trainees but the scope and complexity of the evaluation design will be proportional to the level of investment in these activities. In addition, for training programs without stable funding sources, there are no assurances funding will be available for a long-term evaluation effort. This uncertainty can result in evaluation being a low priority. This also limits the types of questions (especially in regard to career outcomes) that can be asked if data need to be obtained, analyzed, and reported in a limited funding cycle.

If evaluation is a lower priority this could result in training program directors, early in the development of a training program, failing to consider or collect data that would be useful for subsequent evaluation purposes. If long-term follow-up data are not available, the evaluation is limited to using one-time surveys (cross-sectional designs) of program alumni, which was the most common method seen in this literature search. Other issues included that most studies had small sample sizes, which limited statistical analyses and generalizability. Finally, training program leaders may be unsupportive of evaluation because of fear, believing that evaluation findings could be interpreted as showing their programs are “unsuccessful” and placing their programs (or even their own jobs) at risk for funding reductions or elimination.

These barriers to conducting and reporting evaluation of long-term postgraduate training programs need to be overcome since greater emphasis is being placed on collecting and reporting outcomes from postgraduate training program participants. Evaluation data will become even more important in justifying new or sustained funding of training programs. Several ongoing activities at the national level [7, 30] have renewed the call for increased evaluation of these programs. In the absence of substantial progress in developing comprehensive outcomes evaluations of postgraduate training programs, both national and local efforts at improving postgraduate training may suffer. The national committees making workforce recommendations will continue to operate on limited data and without a baseline from which to assess progress and future needs. Individual programs will run the risk of using training methods or activities that are not effective, eliminating or failing to include methods or activities that are, and not having adequate data available to demonstrate the impact of the training program and justify continued resources.

With the current review of the literature demonstrating most training program evaluation study designs are relatively weak at the same time there is increased interest in evaluation of these programs, a few suggestions for improving evaluation efforts are provided here. First and foremost, including more information on demographics (e.g. age, gender, degree) of trainees in evaluation reports would enable comparisons across training programs. At a minimum, reports should also include the type of evaluation study design and the source of the data (e.g. archival records, surveys, CV review) used for the evaluation. The specific evaluation design will depend on the goals and resources of each training program, however, several principles of evaluation are presented here. Table 4 outlines a few evaluation design elements to consider, options for each element, and potential limitations.

Table 4.

Considerations for Training Program Outcomes Evaluation Design

| Evaluation Elements | Approaches | Feasibility | Additional Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Comparison Populations | • Unsuccessful applicants | Requires competitive application process and detailed records to find unsuccessful applicants | Perhaps most similar to alumni since applied for same opportunity |

| • Trainees in similar training program/environment | Need to collaborate with directors of training program that will be the comparison group, requires both programs kept detailed records | Training program directors may fear one program will appear less desirable and will be less likely to collaborate | |

| • No comparison population | Difficult to discern whether outcomes are related to training environment; could use pre-post training comparisons | In pre-post comparison, need to account for effects of time on career outputs and trajectory | |

| 2. Outcome Measures | • Satisfaction/process measures | Can be collected immediately using short surveys; quickly implemented | May be important for program to know satisfaction but not a career outcome |

| • Quantitative outcomes from existing data | Limits evaluation questions that can be asked and may not be applicable to all alumni of training program | Most relevant to academic career paths (e.g. publications, grants, patents); existing data caveats | |

| • Qualitative and quantitative outcomes for diverse career paths | Data collection more complicated but can include measures of career trajectory, peer recognition, professional connectedness | Evaluation measures will be applicable to all alumni; diversity of career paths growing | |

| 3. Data Sources | Existing Data: | Depends on quality and completeness of records | Evaluation designed around questions that can be answered with existing data |

| • Archival Data | Information will be available on only a limited number of outcomes (e.g. publications) | No need to contact alumni directly; some outcomes may be incomplete | |

| New Data Collection: | More resource intensive but can insure data is complete | Can select the most important questions and then collect relevant data to answer them | |

| • CV review | Relying on alumni to periodically send updated CVs; no standard CV format | Can examine career outcomes such as committee service, current job title | |

| • Surveys | Can design survey to specifically address evaluation questions; relying on alumni to complete | Survey can include open-ended questions | |

| • Interviews | In-depth information can be collected; questions can be directed to future program planning | Information collected on limited number of individuals; subjective depending on who participates |

For postgraduate training programs, the issues of comparison populations and length of training complicate the study designs that can be selected. One conundrum is individuals are not randomized to training programs but rather select training programs based on their preferences and are, in turn, selected by program directors to join the training program [22]. In the literature review described here, only one study had a comparison group. It is essential for valid attribution and causal inference regarding the impact of the training program on subsequent career outcomes, to have appropriate comparison groups [33]. “Compared to what?” is the question that needs to be at all times upmost in the evaluator's mind.

Identifying and including comparison groups increases the expense of the evaluation. To decrease costs, two or more programs could combine resources and serve as each other's comparison population, if the programs have similar structure and trainee populations. It may be difficult to find willing participants to serve as a comparison group if there are concerns the evaluation results will frame one program as inferior to the other. Options for different types of comparison groups are explored in Table 4. If no comparison group is utilized, one needs to be mindful of the effect of time on certain outcomes and how this may bias the results [22]. For example, in research-intensive environments, publication number should increase with duration of career and may not be directly attributable to participation in the training program.

Meaningful and appropriate (including time-appropriate) outcome measures that are valid, reliable, relevant to the goals and objectives of the program, and reflect the nature and timing (e.g. what outcomes are to be expected and in what timeframe) of the underlying processes and phenomena need to be selected. It is common mistake to choose outcomes that could not have occurred in the timeframe of the evaluation. Table 4 presents several choices for outcome measures. Ideally, a longer-term outcomes evaluation would use a mixed-methods approach to obtain qualitative and quantitative data. This could include not only quantifying publications, grants awarded or other metrics but also conducting interviews with past trainees to understand what role the trainees think the training program had in their subsequent career trajectory.

Hand-in-hand with deciding on outcome measures, the data sources must be determined (Table 4). Often the archival data sources available for postgraduate training program evaluations contain outcomes most relevant to academic career paths (e.g. grants, publications, patents). Utilizing existing data sources also limits the questions that can be asked during an evaluation to only those for which data already exists. Developing new data collection instruments provides the opportunity to select the most important evaluation questions and then capture the data necessary to answer those questions.

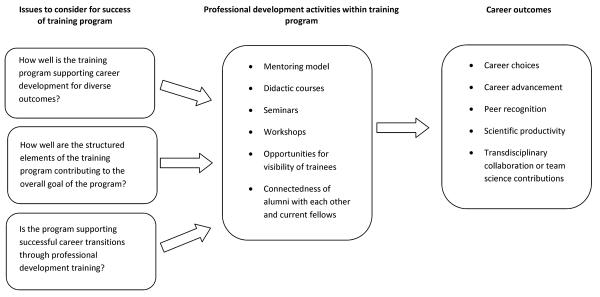

In Figure 1, a diagram containing elements that could be universally applied to evaluating postgraduate public health and biomedical training programs is presented. This evaluation model is “scale-able” depending on funding and timeframe. One could begin with evaluating only individual components of the training program and/or start with only a subset of alumni (e.g. completed program within the last five years). The first column contains examples of questions that would need to be answered to determine if the training program, both as a whole and the individual components of the training program, are meeting the overall goals of the program. The second column contains examples of components of structured training programs. It is important to note training programs may include only a few of these components and these components could focus on specific-areas of research or on professional development (e.g. grant-writing skills, leadership/management skills). The third column indicates types of career outcomes that could be assessed during an evaluation. These outcomes focus on both individual and collaborative contributions and recognition.

Figure 1.

Framework demonstrating examples of questions important to a wide variety of post-graduate training programs, specific components of these training programs, and subsequent evaluation of the impact of the training program on the career outcomes of alumni.

Implicit within this framework is the need to capture as many career outcomes as possible and not focus solely on measures aligned with academic careers. Most postdoctoral fellows will not go on to academic positions [9, 29] where publishing and grantsmanship are the primary measures of productivity. For postdoctoral fellows who choose not to pursue an academic career, there are limited data on the professional fields where postdoctoral fellows find employment and their reasons for pursuing these options. Other outcomes that could be obtained and would apply to alumni across different career paths include assessing career trajectory (e.g. promotions and timing between promotions) and peer recognition. Peer recognition could include appointment to editorial boards, professional society and/or institutional committee service, serving on advisory panels, or nomination for or receipt of awards. This captures a level of connectedness and expertise. For those alumni in academic settings, this will likely track closely with publications and academic rank. It may be less correlated for those alumni in other career paths.

For future outcomes evaluations to provide more insight into the career paths selected by postgraduate trainees, these studies should include methodology for collecting data directly from past trainees rather than relying on archival data sources such as grant and publication databases. In fact, even among the studies included in this literature search, most of the 13 studies included surveys, requested a current CV from participants, and/or another form of personal contact to obtain career outcomes information. Broadening the outcomes explored to include measures that would be applicable to a variety of career paths would provide a more accurate profile from which to assess trainee success across the multitude of career options available to postgraduate trainees in the public health and biomedical sciences.

In conclusion, this literature review demonstrated the lack of published outcomes evaluations of postgraduate public health and biomedical training programs, which is particularly concerning given the number of individuals and investment in these training programs. The recommendations for future evaluations are meant to serve as a starting point for developing a more sophisticated approach, while balancing enthusiasm for the ideal evaluation with the challenges inherent in evaluating long-term postgraduate training programs. A principle message to take from this discussion is to be as rigorous as possible with the evaluation design, within the boundaries imposed or resources available, and to acknowledge the caveats of each decision made. In addition, many training programs have a long history. If evaluation was not considered at the initiation of the program, it is better to start now than not at all, keeping the limitations of retrospective study design in mind. There is a great need to expand on the outcomes collected in evaluation studies so that these studies can be a true reflection of career options and success of past trainees in the postgraduate public health and biomedical workforce. Finally, these results need to be published to inform the design of future training programs and increase the data available to those interested in understanding the postgraduate public health and biomedical workforce career trajectories.

Acknowledgments

We thank Mary Ryan, biomedical librarian/informationist at NIH library, for her help with search terms and conducting literature searches. Aisha Kudura acknowledges summer 2011 fellowship support from the National Cancer Institute's Introduction to Cancer Research Careers and Elaine Nghiem acknowledges summer 2011 fellowship support from the NIH Office of Research on Women's Health and Foundation for Advanced Education in the Sciences. We also thank Drs. Julie Mason and Jonathan Wiest for critical reading of the manuscript and insightful comments.

Footnotes

Jessica Faupel-Badger, David E. Nelson, Stephen Marcus, Aisha Kudura, and Elaine Nghiem have no conflicts of interest or financial disclosures.

References

- 1.The 2002 user friendly handbook for project evaluation . National Science Foundation; Gaithersburg, MD: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Betts CD, Abed JP, Butler MO, Gallogly MO, Goodman KJ, Orians C, et al. Evaluation of the Field Epidemiology Training Program (FETP) Battelle; Arlington, VA: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Buddeberg-Fischer B, Herta KD. Formal mentoring programmes for medical students and doctors--a review of the Medline literature. Med Teach. 2006;28(3):248–257. doi: 10.1080/01421590500313043. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cooksey D. A review of UK health research funding. Stationary Office; London: 2006. [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Research Council . Advancing the nation's health needs: NIH research training programs. National Academies Press; Washington, D.C.: 2005. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cronholm PF, Straton JB, Bowman MA. Methodology and outcomes of a family medicine research fellowship. Acad Med. 2009;84(8):1111–1117. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ace6bc. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Advisory Committee to the National Institutes of Health Director . Biomedical research workforce working group report. National Institutes of Health; Bethesda, MD: 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dores GM, Chang S, Berger VW, Perkins SN, Hursting SD, Weed DL. Evaluating research training outcomes: experience from the cancer prevention fellowship program at the National Cancer Institute. Acad Med. 2006;81(6):535–541. doi: 10.1097/01.ACM.0000225216.07584.b0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fuhrmann CN, Halme DG, O'Sullivan PS, Lindstaedt B. Improving graduate education to support a branching career pipeline: Recommendations based on a survey of doctoral students in the basic biomedical sciences. CBE-Life Sciences Education. 2011;10:239–249. doi: 10.1187/cbe.11-02-0013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibbon M. Higher education relevance in the 21st century. Washington, DC: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Goldberger Marvin L., Maher Brendan A., Flattau Pamela Ebert, National Research Council (U.S.) Committee for the Study of Research-Doctorate Programs in the United States. Conference Board of the Associated Research Councils. National Research Council (U.S.) Office of Scientific and Engineering Personnel. Studies and Surveys Unit . Research-doctorate programs in the United States: continuity and change. National Academy Press; Washington, D.C.: 1995. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gordon SM, Dionne RA. Development and interim results of a clinical research training fellowship. J Dent Educ. 2007;71(8):1040–1047. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Guelich JM, Singer BH, Castro MC, Rosenberg LE. A gender gap in the next generation of physician-scientists: medical student interest and participation in research. J Investig Med. 2002;50(6):412–418. doi: 10.1136/jim-50-06-01. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.National Institutes of Health . The Career Achievements of National Research Service Award Postdoctoral Trainees and Fellows. 2006. pp. 1975–2004. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Hotez PJ. Training the next generation of global health scientists: a school of appropriate technology for global health. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2008;2(8):e279. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0000279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones SR, Filerman GL. An analysis of the impact of the David A. Winston Health Policy Fellowship. J Health Adm Educ. 2007;24(1):33–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Landrigan PJ, Woolf AD, Gitterman B, Lanphear B, Forman J, Karr C, Moshier EL, Godbold J, Crain E. The ambulatory pediatric association fellowship in pediatric environmental health: a 5-year assessment. Environ Health Perspect. 2007;115(10):1383–1387. doi: 10.1289/ehp.10015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Laredo P. Revisiting the third mission of universities: toward a renewed categorization of university activities? Higher Education Policy. 2007;20(4):441–456. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lopez A, Caceres VM. Central America Field Epidemiology Training Program (CA FETP): a pathway to sustainable public health capacity development. Human Resources for Health. 2008;6:27. doi: 10.1186/1478-4491-6-27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Matovu JK, Wanyenze RK, Mawemuko S, Wamuyu-Maina G, Bazeyo W, Olico Okui, Serwadda D. Building capacity for HIV/AIDS program leadership and management in Uganda through mentored Fellowships. Glob Health Action. 2011;4:5815. doi: 10.3402/gha.v4i0.5815. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pion G, Ionescu-Pioggia M. Bridging postdoctoral training and a faculty position: initial outcomes of the Burroughs Wellcome Fund Career Awards in the Biomedical Siences. Acad Med. 2003;78(2):177–186. doi: 10.1097/00001888-200302000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pion GM, Cordray DS. The Burroughs Welcome Fund Career Awards in the Biomedical Sciences: challenges to and prospects for estimating the causal effects of career development programs. Evaluation & the Health Professions. 2008;31:335–369. doi: 10.1177/0163278708324434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Rip A. Strategic research, post-modern universities, and research training. Higher Education Policy. 2004;17(2):153–166. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rivera R, Kirby DF, Steiger E, Seidner DL. Professional outcomes of completing a clinical nutrition fellowship: Cleveland clinic's 16-Year experience. Nutrition in Clinical Practice. 2010;25(5):497–501. doi: 10.1177/0884533610379853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rose SH, Long TR, Kor DJ, Onigkeit JA, Brown DR. Anesthesiology critical care medicine: a fellowship and faculty recruitment program. Journal of Clinical Anesthesia. 2011;23:261–264. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2011.02.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rossi PH, Lipsey MW, Freeman HE. Evaluation: a systematic approach. 7th Ed. Sage; Thousand Oaks, CA: 2003. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Sakalys JA, Stember ML, Magilvy JK. Nursing doctoral program evaluation: Alumni outcomes. J Prof Nurs. 2001;17(2):87–95. doi: 10.1053/jpnu.2001.22277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Sambunjak D, Straus SE, Marusic A. Mentoring in academic medicine: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1103–1115. doi: 10.1001/jama.296.9.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sauermann H, Roach M. Science PhD Career Preferences: Levels, Changes, and Advisor Encouragement. PLoS One. 7(5):e36307. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0036307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.National Academy of Sciences [Accessed August 6 2012];Committe to review the state of the postdoctoral experience for scientists and engineers. 2012 http://sites.nationalacademies.org/PGA/COSEPUP/Postdoc-2011/.

- 31.National Academy of Sciences, National Academy of Engineering, and Institute of Medicine . Enhancing the Postdoctoral Experience for Scientists and Engineers: A Guide for Postdoctoral Scholars, Advisers, Institutions, Funding Organizations, and Disciplinary Societies. The National Academies Press; 2000. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.National Institute of General Medical Sciences . MSTP Study: The Careers and Professional Activities of Graduates of the NIGMS Medical Scientist Training Program. 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shadish WR, Cook TD, Campbell DT. Experimental and quasi-experimental designs for causal inference. 2nd Ed. Houghton-Mifflin; Boston, MA: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Simon SR, Shaneyfelt TM, Collins MM, Cook EF, Fletcher RH. Faculty training in general internal medicine: a survey of graduates from a research-intensive fellowship program. Academic Medicine. 1999;74(11):1253–1255. doi: 10.1097/00001888-199911000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Summers MF. Training the next generation of protein scientists. Protein Science. 2011;29:1786–1801. doi: 10.1002/pro.733. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Thacker SB, Dannenberg AL, Hamilton DH. Epidemic intelligence service of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: 50 years of training and service in applied epidemiology. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154(11):985–992. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.11.985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Waterbor JW, Heimburger DC, Fish L, Etten TJ, Brooks CM. An interdisciplinary cancer prevention and control training program in public health. J Cancer Educ. 2002;17(2):85–91. doi: 10.1080/08858190209528805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]