Abstract

Objective

To provide a clinical summary of the Canadian clinical practice guidelines for chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) that includes recommendations relevant for family physicians.

Quality of evidence

Guideline authors performed a systematic literature search and drafted recommendations. Recommendations received both strength of evidence and strength of recommendation ratings. Input from external content experts was sought, as was endorsement from Canadian medical societies (Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada, Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Canadian Society of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, and Family Physicians Airways Group of Canada).

Main message

Diagnosis of CRS is based on type and duration of symptoms and an objective finding of inflammation of the nasal mucosa or paranasal sinuses. Chronic rhinosinusitis is categorized based on presence or absence of nasal polyps, and this distinction leads to differences in treatment. Chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps is treated with intranasal corticosteroids. Antibiotics are recommended when symptoms indicate infection (pain or purulence). For CRS without nasal polyps, intranasal corticosteroids and second-line antibiotics (ie, amoxicillin– clavulanic acid combinations or fluoroquinolones with enhanced Gram-positive activity) are recommended. Saline irrigation, oral steroids, and allergy testing might be appropriate. Failure of response should prompt consideration of alternative diagnoses and referral to an otolaryngologist. Patients undergoing endoscopic sinus surgery require postoperative treatment and follow-up.

Conclusion

The Canadian guidelines provide diagnosis and treatment approaches based on the current understanding of the disease and available evidence. Additionally, the guidelines provide the expert opinion of a diverse group of practice and academic experts to help guide clinicians where evidence is sparse.

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is an inflammatory disease of the sinuses that has a reported prevalence of 5% in Canada.1–3 The prevalence increases with age, and is higher for women, individuals with asthma, individuals with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and those with a history of allergy.1 The disease has a substantial effect on patient quality of life, with one study reporting a similar health status between patients with CRS and those with cancer, asthma, or arthritis.3 Another study reported worse social functioning and more bodily pain in patients with CRS versus those with angina, back pain, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or congestive heart failure.4 Not surprisingly, CRS consumes substantial health care resources. In 2008, 12.5 million office visits were made for CRS in the United States.5 A study of 2007 data from the Medical Expenditure Panel Survey estimated the health care cost of CRS in the United States at $8.6 billion per year.6

Although CRS is a disease distinct from acute bacterial rhinosinusitis (ABRS), prescription data from Canada reveal that prescribing habits for antibiotics are comparable between both types of disease.7 The recently published Canadian guidelines8,9 for diagnosing and treating CRS help shed light on the evolving understanding of CRS and treatment strategies. Because of the chronic nature of CRS, patients with this disease should be actively managed and receive regular follow-up. Use of the new guidelines should help busy clinicians stay up to date with current diagnostic and treatment approaches for managing their patients with CRS.

Quality of evidence

Guideline authors performed a systematic literature search and drafted recommendations. Recommendations received both strength of evidence and strength of recommendation ratings. Input from external content experts was sought, as was endorsement from Canadian medical societies (Association of Medical Microbiology and Infectious Disease Canada, Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, Canadian Society of Otolaryngology—Head and Neck Surgery, Canadian Association of Emergency Physicians, and Family Physicians Airways Group of Canada).

Main message

Pathophysiology

Chronic rhinosinusitis is a complex inflammatory disease that is not well understood. It is proposed that bacteria contribute to persistence of disease via chronic infection, antibiotic-resistant strains, or the presence of bacterial biofilms. However, the role and contributions of intense inflammation, bacteria, fungi, immunopathologic mechanisms, airway remodeling, susceptibility factors, and environmental contributions remain unclear. Because CRS subtypes present with different pathogenic mechanisms, it has been argued that CRS represents a syndrome of characteristic symptoms rather than a distinct disease.10

Despite the uncertainty in pathophysiology, it is known that the bacterial landscape in CRS differs from ABRS, with Staphylococcus aureus, Enterobacteriaceae spp, and Pseudomonas spp (especially Pseudomonas aeruginosa) predominating rather than Streptococcus pneumoniae and Haemophilus influenzae, which are the important pathogens in ABRS. However, the role of bacteria in CRS is uncertain given that only about half of patients undergoing surgery for CRS have positive bacterial culture results.11

Diagnosis

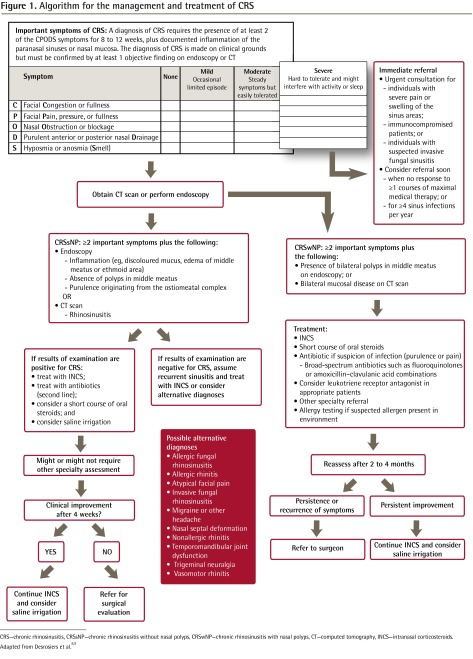

The guidelines propose a mnemonic device, CPODS (Congestion or fullness; facial Pain, pressure, or fullness; nasal Obstruction or blockage; purulent anterior or posterior nasal Drainage; and Smell disorder), to assist recall of the important symptoms of CRS (Figure 1).8,9 Diagnosis of CRS requires the presence of at least 2 important symptoms for at least 8 weeks, plus objective documentation of sinus inflammation with endoscopy or computed tomography (CT).12–18 Neither symptoms alone nor objective findings alone are sufficient to make a diagnosis because symptoms are similar to those for upper respiratory tract infections and migraine headaches, and positive imaging results can be found in healthy individuals. Thus, diagnosis requires a thorough physical examination and medical history.

Figure 1.

Algorithm for the management and treatment of CRS

CRS—chronic rhinosinusitis, CRSsNP—chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps, CRSwNP—chronic rhinosinusitis with nasal polyps, CT—computed tomography, INCS—intranasal corticosteroids.

For the physical examination, an otoscope, or headlight and nasal speculum, can provide sufficient illumination to examine the nasal septum, middle meatal area, and inferior turbinates. A systematic evaluation of these areas should be performed (Box 1). Sinonasal endoscopy should be performed by an otolaryngologist to confirm suspected CRS. This assessment provides a more thorough inspection of the nasal cavity and sinuses, and permits detection of early-stage polyps. If you believe you need a review on nasal endoscopy, please view the training video on www.sinuscanada.com (the password to enter the site is sinus).

Box 1. Physical examination: A topical decongestant (eg, oxymetazoline or xylometazoline) can assist with visualization.

Systematically evaluate the nasal septum, middle meatal area, and inferior turbinates

Identify:

Ulceration, bleeding ulceration, drying crusts, and perforation in nasal septum

Anatomic obstructions

Substantial septal deflections

Unusual presentation of the nasal mucosa

Unusual colour and condition of the nasal mucosa (healthy is pinkish-orange and moist)

Dryness or hypersecretion of the nasal mucosa

Hypertrophy of turbinates

Presence of nasal masses or secretions

Red flags that indicate referral

Persistent crusts (consideration of other conditions such as Wegener granulomatosis)

Irregular surfaces

Diffusely hemorrhagic areas

Vascular malformations of ectasias

Bleeding resulting from minor trauma

Chronic rhinosinusitis can be subcategorized as CRS with nasal polyps (CRSwNP) or CRS without nasal polyps (CRSsNP)16 (Figure 1).8,9

Although both subtypes share similar symptoms, it has been noted that hyposmia is more frequent with CRSwNP, while facial pain, pressure, or fullness is more often associated with CRSsNP.

Role of imaging and other testing: In the case of CRSsNP, endoscopy can be used to document signs of inflammation (eg, edema of the middle meatus, edema of the ethmoid area, or discoloured mucus) and purulence in the ostiomeatal complex needed for a diagnosis. Alternatively, a CT scan can be used to provide evidence of inflammation. When a CT scan is performed, a coronal view is preferred.

In the case of CRSwNP, objective documentation includes the presence of polyps confirmed by endoscopy and the presence of bilateral mucosal disease confirmed by CT.

It should be cautioned that imaging-confirmed inflammation suggestive of CRS is found in up to 42% of asymptomatic individuals.19,20 For this reason, objective findings alone are insufficient to make a diagnosis of CRS. Findings must be supported with clinical symptoms.

Imaging is also indicated for CRS that does not respond to maximal medical management. In such cases, a noncontrast coronal CT scan of the sinuses should be ordered. In addition, a detailed CT scan might be ordered by an otolaryngologist who is planning surgical intervention.

Bacterial culture from patients with CRS is unnecessary except in situations of serious complications (eg, intracranial extension, orbital infection) or for patients with nosocomial sinusitis. In these cases, referral to an otolaryngologist is recommended for endoscopic culture of the middle meatus. Results can then be used to help direct treatment. Invasive fungal sinusitis, while rare in healthy populations, can be life-threatening and should be considered in those who are immunocompromised; it requires urgent referral for assessment and treatment.

Alternative diagnoses: For patients whose CRS does not respond to medical therapy, other conditions should be considered, including allergic fungal rhinosinusitis, invasive fungal rhinosinusitis, allergic rhinitis, nonallergic rhinitis, vasomotor rhinitis, nasal septal deformation, atypical facial pain, migraine or headache, temporomandibular joint dysfunction, and trigeminal neuralgia.17

Treatment

The first step in managing patients with CRS involves identifying and addressing contributing factors (Box 2).10,21 Allergy is commonly associated with CRS that does not respond to treatment,22 and allergy testing can identify patients whose symptoms might in part respond to allergy treatment. Similarly, in cases of treatment-resistant CRS, testing immune function might reveal dysfunction such as immunoglobulin G deficiency.23,24

Box 2. Contributing factors to the development of chronic rhinosinusitis.

|

The goal of therapy is to reduce symptoms and complications by minimizing inflammation and controlling the infectious components of CRS. Therapy for CRS is based on intranasal corticosteroids (INCSs) with or without antibiotics, depending on the presence or absence of symptoms of infection (Figure 1).8,9 Chronic rhinosinusitis without nasal polyps is often associated with a bacterial infection, thus initial therapy includes both INCSs and antibiotics. Because therapy is typically empiric, antibiotic choice centres on broad-spectrum agents that target enteric Gram-negative organisms, S aureus, and anaerobes, as well as the less commonly encountered S pneumoniae, H influenzae, and Moraxella catarrhalis. Thus, fluoroquinolones or amoxicillin–clavulanate acid combinations are recommended for initial treatment of CRSsNP. In addition, a short course of oral steroids should be considered for patients with severe or persistent symptoms.

Initial therapy for CRSwNP is INCSs, with the addition of oral steroids in symptomatic patients. For patients with acetylsalicylic acid sensitivity, trials of leukotriene receptor antagonists might be considered. For patients with CRSwNP and pain, documented purulence, or recurrent episodes of sinusitis, bacterial infection should be suspected and antibiotics initiated (directed either empirically or by culture).

Steroids have also been found to be useful in treating CRS. For patients with severe polypoid disease that was unresponsive to INCS therapy, a 2-week course of prednisone (eg, 30 mg/d for 4 days, then the dose reduced by 5 mg every 2 days for 10 days) reduced polyp size or grade, with INCSs then being used to maintain this improvement.25–27 Systemic prednisone (eg, 30 mg/d) given 5 days before and 9 days after endoscopic sinus surgery (ESS) was shown to provide benefit.28 When prescribing oral steroids, the minimally effective dose should always be used to reduce the risk of serious adverse events.29 In addition, it is always necessary to document the discussion with the patient about the risks of systemic steroids to avoid potential litigation down the road.30

Evidence for therapies: Intranasal corticosteroids have been shown to shrink nasal polyps and improve nasal symptoms in patients with CRSwNP.31–35 In addition to reduced polyp size, studies of mometasone furoate have reported improvements in nasal congestion and obstruction,33–35 anterior rhinorrhea, postnasal drip, and loss of sense of smell.33 Similarly, reduced polyp size and improved symptoms have been reported in studies of budesonide versus placebo.31,32

The efficacy of INCSs in treating patients with CRSsNP has been less clear,36,37 largely because of small study sizes and limitations of trial designs. Because no long-term adverse effects have been reported with INCS use, they are recommended for the treatment of CRSsNP owing to their anti-inflammatory properties. Their role in treatment might evolve as more rigorous clinical trials shed light on their efficacy in this patient population.

There are no rigorous placebo-controlled studies of antibiotics in the treatment of CRS. The clinical cure and bacteriologic eradication rates were 58.6% versus 51.2% and 88.9% versus 90.5% for ciprofloxacin and amoxycillin– clavulanic acid, respectively,38 and 65% versus 68% and 95% versus 98% for amoxycillin–clavulanic acid and cefuroxime.39 However, sensitivities might have changed since these studies were performed.

Adjunct therapies: Saline irrigation has been shown to improve symptoms in patients with CRS.40 Although there are no rigorous data to support the use of mucolytics, antihistamines, or decongestants in CRS, these agents theoretically should help improve symptoms. It should be cautioned that long-term use of topical decongestants should be avoided to prevent exacerbating CRS via development of rhinitis medicamentosa.41 There is limited evidence that leukotriene modifiers alleviate symptoms in patients with nasal polyps, suggesting they might be considered for some patients when appropriate.42,43

Surgery: Endoscopic sinus surgery is reserved for patients whose CRS does not respond to medical therapy. Endoscopic sinus surgery is used to remove diseased mucosa, relieve obstruction, and restore ventilation. Although the efficacy of ESS over the long term has been debated,44 studies report substantial improvement in patient quality of life.45–47 When considering surgery, the risks of lengthy courses of oral steroids and antibiotics should be considered against the risk of substantial complications from ESS, which was recently reported to be 1%.48 Another study reported an overall complication rate of 5.8% following ESS, with 0.1% representing substantial complications.49

Among the CRS cases that prove difficult to cure using medical management alone, most patients have a combination of pathophysiologic and anatomic factors that support chronic inflammation and bacterial presence.50 Referral to an otolaryngologist is necessary to evaluate for possible ESS and to attempt maximal medical therapy (if not already given). If surgery is pursued, proper medical therapy before and after surgery is critical to ensuring success, and should be ordered by the surgeon. Preoperative and postoperative use of systemic steroids has been shown to result in clinically healthier sinus cavities compared with those of patients not receiving prednisone in the perioperative period.28

Postoperative care for ESS patients varies among surgeons.51,52 Use of antibiotics immediately after surgery, saline irrigation, and debridement in the office were relatively consistent post-ESS approaches.51 Severe pain, fever, or new-onset coloured secretions warrant immediate referral to the operating surgeon. For longer-term management after ESS, saline irrigation is recommended, and INCSs are an option. Intranasal corticosteroids after ESS have shown efficacy in patients with CRS. In one study of patients with allergy and CRS, 85% of those receiving budesonide reported symptom improvement.53 Another study of patients with CRSwNP reported an 89% success rate (ie, with respect to risk of failure) 5 years after ESS.54 However, other studies reported similar rates of polyp recurrence at 1 year with or without INCS use.55 In another study, time to relapse (defined as a 1-point increase on a polyp scoring system scale of 0 to 6 points) was longer for patients receiving INCS versus placebo after ESS (175 days vs 125 days, P = .049).56

Role of the family physician

Family physicians play a critical role in the management of patients with CRS. Monitoring for acute exacerbations of CRS, redirecting therapy when needed, supplying additional specialist referral and testing when appropriate, providing education and support to patients, and interacting with other specialists as part of a clinical care team can help improve the lives of patients with this chronic disease.

Patients with CRS should be advised to avoid allergic triggers, environments where exposure to infective agents is likely (eg, day cares, health care centres), smoking, and acute exacerbations. Clinicians should closely monitor their patients with asthma, mucosal eosinophilic leukocyte CRS, or with high peripheral eosinophilic leukocyte counts, as they are at risk of recurrence.57 Referral to an otolaryngologist should be made to confirm a diagnosis, to obtain endoscopic culture to direct medical therapy, and to address and prevent complications (Box 3).

Box 3. Indications for referral: Evidence is grade D (based on expert consensus) and recommendations are strong.

Urgent referral

Severe symptoms of pain or swelling of the sinuses

Immunocompromised patients

Suspected invasive fungal sinusitis

Referral

Failure of maximal medical therapy (allergen avoidance measures, topical steroids, nasal irrigation, systemic antibiotics)

Having 4 or more sinus infections per year

Conclusion

Chronic rhinosinusitis is a challenging disease to manage owing to our incomplete knowledge about the many interacting factors that contribute to its development and persistence. Additionally, rigorous clinical trials that assess efficacy and safety of therapies in different CRS types are lacking. Despite these challenges, family physicians play a pivotal role in helping their patients with CRS proactively manage the disease and acute exacerbations. The Canadian guidelines for CRS offer up-to-date guidance to assist clinicians with the diagnostic process and recommendations for treatment.

Acknowledgments

I thank Dr Lynne Isbell for editorial support.

EDITOR’S KEY POINTS

Chronic rhinosinusitis (CRS) is an inflammatory disease of the sinuses that has a reported prevalence of 5% in Canada. The condition has a substantial effect on patient quality of life and leads to consumption of substantial health care resources.

Because of the chronic nature of CRS, patients with this disease should be actively managed and receive regular follow-up. The most recent guidelines, published in 2011, should help busy clinicians stay up to date with current diagnostic and treatment approaches for managing their patients with CRS. This article provides a clinical summary of the guidelines relevant for family physicians.

Family physicians play a critical role in the management of patients with CRS. Monitoring for acute exacerbations, redirecting therapy when needed, supplying additional referral and testing when appropriate, providing education and support to patients, and interacting with other specialists as part of a clinical care team can help improve the lives of patients with this chronic disease.

Footnotes

This article is eligible for Mainpro-M1 credits. To earn credits, go to www.cfp.ca and click on the Mainpro link.

This article has been peer reviewed.

La traduction en français de cet article se trouve à www.cfp.ca dans la table des matières du numéro de décembre 2013 à la page e528.

Competing interests

Dr Kaplan has served on advisory boards for and received honoraria for giving lectures from AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Merck, Novartis, Pfizer, Purdue, and Takeda. He received no funding for creating this paper. The editorial support was acquired with funds from the dissemination strategy of the Canadian sinusitis clinical guidelines group.

References

- 1.Chen Y, Dales R, Lin M. The epidemiology of chronic rhinosinusitis in Canadians. Laryngoscope. 2003;113(7):1199–205. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200307000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Joe SA, Thambi R, Huang J. A systematic review of the use of intranasal steroids in the treatment of chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139(3):340–7. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2008.05.628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Macdonald KI, McNally JD, Massoud E. The health and resource utilization of Canadians with chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2009;119(1):184–9. doi: 10.1002/lary.20034. Epub 2008 Dec 31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gliklich RE, Metson R. The health impact of chronic sinusitis in patients seeking otolaryngologic care. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1995;113(1):104–9. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989570152-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey: 2008 summary tables. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2008. Available from: www.cdc.gov/nchs/data/ahcd/namcs_summary/2008_namcs_web_tables.pdf. Accessed 2013 Oct 29. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bhattacharyya N. Incremental health care utilization and expenditures for chronic rhinosinusitis in the United States. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2011;120(7):423–7. doi: 10.1177/000348941112000701. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Disease and Therapeutic Index. 03/2003-03/2004. Danbury, CT: IMS Health; Available from: www.imsservicecatalog.com. Accessed 2009 Jul 1. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Desrosiers M, Evans GA, Keith PK, Wright ED, Kaplan A, Bouchard J, et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. Allergy Asthma Clin Immunol. 2011;7(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1710-1492-7-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Desrosiers M, Evans GA, Keith PK, Wright ED, Kaplan A, Bouchard J, et al. Canadian clinical practice guidelines for acute and chronic rhinosinusitis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;40(Suppl 2):S99–193. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schleimer RP, Kato A, Peters A, Conley D, Kim J, Liu MC, et al. Epithelium, inflammation, and immunity in the upper airways of humans: studies in chronic rhinosinusitis. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2009;6(3):288–94. doi: 10.1513/pats.200808-088RM. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Desrosiers M, Hussain A, Frenkiel S, Kilty S, Marsan J, Witterick I, et al. Intranasal corticosteroid use is associated with lower rates of bacterial recovery in chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;136(4):605–9. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2006.10.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bousquet J, Van Cauwenberge P, Khaltaev N, Aria Workshop Group. World Health Organization Allergic rhinitis and its impact on asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2001;108(5 Suppl):S147–334. doi: 10.1067/mai.2001.118891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Fokkens W, Lund V, Bachert C, Clement P, Hellings P, Holmstrom M, et al. EAACI position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps executive summary. Allergy. 2005;60(5):583–601. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2005.00830.x. Epub 2005 Apr 6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lanza DC, Kennedy DW. Adult rhinosinusitis defined. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1997;117(3 Pt 2):S1–7. doi: 10.1016/S0194-59989770001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, Lanza DC, Marple BF, Nicklas RA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: establishing definitions for clinical research and patient care. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2004;114(6 Suppl):155–212. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2004.09.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Meltzer EO, Hamilos DL, Hadley JA, Lanza DC, Marple BF, Nicklas RA, et al. Rhinosinusitis: developing guidance for clinical trials. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(5 Suppl):S17–61. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld RM, Andes D, Bhattacharyya N, Cheung D, Eisenberg S, Ganiats TG, et al. Clinical practice guideline: adult sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137(3 Suppl):S1–31. doi: 10.1016/j.otohns.2007.06.726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Small P, Frenkiel S, Becker A, Boisvert P, Bouchard J, Carr S, et al. Rhinitis: a practical and comprehensive approach to assessment and therapy. J Otolaryngol. 2007;36(Suppl 1):S5–28. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bolger WE, Parsons DS, Butzin CA. Paranasal sinus bony anatomic variations and mucosal abnormalities: CT analysis for endoscopic sinus surgery. Laryngoscope. 1991;101(1 Pt 1):56–64. doi: 10.1288/00005537-199101000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Flinn J, Chapman ME, Wightman AJ, Maran AG. A prospective analysis of incidental paranasal sinus abnormalities on CT head scans. Clin Otolaryngol Allied Sci. 1994;19(4):287–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2273.1994.tb01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Van Cauwenberge P, Van Hoecke H, Bachert C. Pathogenesis of chronic rhinosinusitis. Curr Allergy Asthma Rep. 2006;6(6):487–94. doi: 10.1007/s11882-006-0026-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Emanuel IA, Shah SB. Chronic rhinosinusitis: allergy and sinus computed tomography relationships. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2000;123(6):687–91. doi: 10.1067/mhn.2000.110961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Chee L, Graham SM, Carothers DG, Ballas ZK. Immune dysfunction in refractory sinusitis in a tertiary care setting. Laryngoscope. 2001;111(2):233–5. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200102000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Vanlerberghe L, Joniau S, Jorissen M. The prevalence of humoral immunodeficiency in refractory rhinosinusitis: a retrospective analysis. B-ENT. 2006;2(4):161–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Alobid I, Benitez P, Pujols L, Maldonado M, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Morello A, et al. Severe nasal polyposis and its impact on quality of life. The effect of a short course of oral steroids followed by long-term intranasal steroid treatment. Rhinology. 2006;44(1):8–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Benítez P, Alobid I, de Haro J, Berenquer J, Bernal-Sprekelsen M, Pujols L, et al. A short course of oral prednisone followed by intranasal budesonide is an effective treatment of severe nasal polyps. Laryngoscope. 2006;116(5):770–5. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000205218.37514.0f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Patiar S, Reece P. Oral steroids for nasal polyps. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(1):CD005232. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005232.pub2. Update in: Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2011;(7): CD005232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wright ED, Agrawal S. Impact of perioperative systemic steroids on surgical outcomes in patients with chronic rhinosinusitis with polyposis: evaluation with the novel Perioperative Sinus Endoscopy (POSE) scoring system. Laryngoscope. 2007;117(11 Pt 2 Suppl 115):1–28. doi: 10.1097/MLG.0b013e31814842f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Fokkens W, Lund V, Mullol J. European Position Paper on Rhinosinusitis and Nasal Polyps group. European position paper on rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 2007. Rhinol Suppl. 2007;(20):1–136. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Nash JJ, Nash AG, Leach ME, Poetker DM. Medical malpractice and corticosteroid use. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2011;144(1):10–5. doi: 10.1177/0194599810390470. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Filiaci F, Passali D, Puxeddu R, Schrewelius C. A randomized controlled trial showing efficacy of once daily intranasal budesonide in nasal polyposis. Rhinology. 2000;38(4):185–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jankowski R, Schrewelius C, Bonfils P, Saban Y, Gilain L, Prades JM, et al. Efficacy and tolerability of budesonide aqueous nasal spray treatment in patients with nasal polyps. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2001;127(4):447–52. doi: 10.1001/archotol.127.4.447. Epub 2005 Sep 26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Small CB, Hernandez J, Reyes A, Schenkel E, Damiano A, Stryszak P, et al. Efficacy and safety of mometasone furoate nasal spray in nasal polyposis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2005;116(6):1275–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2005.07.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Stjärne P, Blomgren K, Cayé-Thomasen P, Salo S, Søderstrøm T. The efficacy and safety of once-daily mometasone furoate nasal spray in nasal polyposis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Acta Otolaryngol. 2006;126(6):606–12. doi: 10.1080/00016480500452566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Stjärne P, Mösges R, Jorissen M, Passàli D, Bellussi L, Staudinger H, et al. A randomized controlled trial of mometasone furoate nasal spray for the treatment of nasal polyposis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2006;132(2):179–85. doi: 10.1001/archotol.132.2.179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lund VJ, Black JH, Szabó LZ, Schrewelius C, Akerlund A. Efficacy and tolerability of budesonide aqueous nasal spray in chronic rhinosinusitis patients. Rhinology. 2004;42(2):57–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Parikh A, Scadding GK, Darby Y, Baker RC. Topical corticosteroids in chronic rhinosinusitis: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial using fluticasone propionate aqueous nasal spray. Rhinology. 2001;39(2):75–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Legent F, Bordure P, Beauvillain C, Berche P. A double-blind comparison of ciprofloxacin and amoxycillin/clavulanic acid in the treatment of chronic sinusitis. Chemotherapy. 1994;40(Suppl 1):8–15. doi: 10.1159/000239310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Namyslowski G, Misiolek M, Czecior E, Malafiej E, Orecka B, Namyslowski P, et al. Comparison of the efficacy and tolerability of amoxycillin/clavulanic acid 875 mg b.i.d. with cefuroxime 500 mg b.i.d. in the treatment of chronic and acute exacerbation of chronic sinusitis in adults. J Chemother. 2002;14(5):508–17. doi: 10.1179/joc.2002.14.5.508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, Scadding G. Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2007;(3):CD006394. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD006394.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Graf P, Enerdal J, Hallén H. Ten days’ use of oxymetazoline nasal spray with or without benzalkonium chloride in patients with vasomotor rhinitis. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;125(10):1128–32. doi: 10.1001/archotol.125.10.1128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Parnes SM, Chuma AV. Acute effects of antileukotrienes on sinonasal polyposis and sinusitis. Ear Nose Throat J. 2000;79(1):18–20. 24–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ulualp SO, Sterman BM, Toohill RJ. Antileukotriene therapy for the relief of sinus symptoms in aspirin triad disease. Ear Nose Throat J. 1999;78(8):604–6. 608, 613. passim. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Khalil HS, Nunez DA. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;(3):CD004458. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004458.pub2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Durr DG, Desrosiers M. Evidence-based endoscopic sinus surgery. J Otolaryngol. 2003;32(2):101–6. doi: 10.2310/7070.2003.37123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Smith TL, Mendolia-Loffredo S, Loehrl TA, Sparapani R, Laud PW, Nattinger AB. Predictive factors and outcomes in endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Laryngoscope. 2005;115(12):2199–205. doi: 10.1097/01.mlg.0000182825.82910.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Macdonald KI, McNally JD, Massoud E. Quality of life and impact of surgery on patients with chronic rhinosinusitis. J Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;38(2):286–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ramakrishnan VR, Kingdom TT, Nayak JV, Hwang PH, Orlandi RR. Nationwide incidence of major complications in endoscopic sinus surgery. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2(1):34–9. doi: 10.1002/alr.20101. Epub 2011 Nov 8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Asaka D, Nakayama T, Hama T, Okushi T, Matsuwaki Y, Yoshikawa M, et al. Risk factors for complications of endoscopic sinus surgery for chronic rhinosinusitis. Am J Rhinol Allergy. 2012;26(1):61–4. doi: 10.2500/ajra.2012.26.3711. Epub 2013 Jan 9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Evans KL. Recognition and management of sinusitis. Drugs. 1998;56(1):59–71. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199856010-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Portela RA, Hootnick J, McGinn J. Perioperative care in functional endoscopic sinus surgery: a survey study. Int Forum Allergy Rhinol. 2012;2(1):27–33. doi: 10.1002/alr.20098. Epub 2011 Oct 24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sindwani R, Wright ED, Janzen VD, Chandarana S. Perioperative management of the sinus patient: a Canadian perspective. J Otolaryngol. 2003;32(3):155–9. doi: 10.2310/7070.2003.40286. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lavigne F, Cameron L, Renzi PM, Planet JF, Christodoulopoulos P, Lamkioued B, et al. Intrasinus administration of topical budesonide to allergic patients with chronic rhinosinusitis following surgery. Laryngoscope. 2002;112(5):858–64. doi: 10.1097/00005537-200205000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rowe-Jones JM, Medcalf M, Durham SR, Richards DH, Mackay IS. Functional endoscopic sinus surgery: 5 year follow up and results of a prospective, randomised, stratified, double-blind, placebo controlled study of postoperative fluticasone propionate aqueous nasal spray. Rhinology. 2005;43(1):2–10. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dijkstra MD, Ebbens FA, Poub lon RM, Fokkens WJ. Fluticasone propionate aqueous nasal spray does not influence the recurrence rate of chronic rhinosinusitis and nasal polyps 1 year after functional endoscopic sinus surgery. Clin Exp Allergy. 2004;34(9):1395–400. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2222.2004.02044.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Stjärne P, Olsson P, Alenius M. Use of mometasone furoate to prevent polyp relapse after endoscopic sinus surgery. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2009;135(3):296–302. doi: 10.1001/archoto.2009.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matsuwaki Y, Ookushi T, Asaka D, Mori E, Nakajima T, Yoshida T, et al. Chronic rhinosinusitis: risk factors for the recurrence of chronic rhinosinusitis based on 5-year follow-up after endoscopic sinus surgery. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2008;146(Suppl 1):77–81. doi: 10.1159/000126066. Epub 2008 May 27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]