Abstract

Introduction

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the most lethal manifestation of heart disease. In an Indian study the SCDs contribute about 10% of the total mortality and SCD post ST elevation myocardial infarction (MI) constitutes for about half of total deaths.

Objective

Given the limitations of existing therapy there is a need for an effective, easy to use, broadly applicable and affordable intervention to prevent SCD post MI. Leading cardiologists from all over India came together to discuss the potential role of n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) 460 mg & docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) 380 mg in the management of post MI patients and those with hypertriglyceridemia.

Recommendations

Highly purified & concentrated omega-3 ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) has clinically proven benefits in improving post MI outcomes (significant 15% risk reduction for all-cause mortality, 20% risk reduction for CVD and 45% risk reduction in SCD in GISSI-Prevenzione trial) and in reducing hypertriglyceridemia, and hence, represent an interesting option adding to the treatment armamentarium in the secondary prevention after MI based on its anti-arrhythmogenic effects and also in reducing hypertriglyceridemia.

Keywords: Sudden cardiac death, Myocardial infarction, Hypertriglyceridemia, Omega-3-acid ethyl esters, Eicosapentaenoic acid & docosahexaenoic acid

1. Overview

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the most lethal manifestation of heart disease.1 South Asians are known to have a high prevalence of coronary risk factors and develop ischemic heart disease (IHD) at an earlier age than in developed countries. It is projected that by the end of this decade, 60% of the world's heart disease cases will occur in India.2 However, the proportion of cardiovascular deaths that are SCD events and the risk factor profile of the individuals at risk for SCD in India remain largely unknown.3 In an Indian study the SCDs contribute about 10% of the total mortality and SCD post ST elevation myocardial infarction (MI) constitutes for about half of total deaths. SCD involves younger population and most of these deaths occur within the first year, particularly in the first month.2,3

Of the various pharmacological treatment modalities available, only β-blockers and amiodarone have been shown to be of some benefit in reducing SCD following MI. Implantable cardioverter-defibrillator (ICD) has emerged as the most successful therapeutic option, but it has its own limitations of cost and availability, precluding its wide application.4–6

2. Need for new therapeutic options

Given the limitations of existing therapy there is a need for an effective, easy to use, broadly applicable and affordable intervention to prevent SCD post MI. Highly purified Omega (n)-3 ethyl ester concentrate of eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA) & docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) has emerged as a candidate therapy. The human body can synthesize unsaturated omega-3 fatty acids like EPA and DHA from α-linolenic acid (ALA) only to a limited extent; hence accumulation of effective concentration of long-chain omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) in tissues is dependent on oral intake.5–7

2.1. Potential benefits & proposed mechanisms contributing to survival benefit with omega-3 ethyl ester concentrate of EPA and DHA

Various benefits of EPA and DHA supplementation have been proposed. Some of these are mentioned below.1,8–12

|

|

2.2. A long chain n-3 acid ethyl esters of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg)

The concentration of omega-3 PUFA in most fish oils is far below the recommended levels and also has inadequate concentration of EPA and DHA which have shown to be of actual benefit in patients with MI.13,14 n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) provides long chain ethyl ester concentrate in a concentration of up to 84% [EPA (460 mg) + DHA (380 mg) per g] thereby fulfilling the recommendations provided by American Heart Association (AHA), National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) and European Society of Cardiology (ESC). A single capsule provides better compliance and has low concentration of other medium and longer chain saturated FA, thereby promising an improved efficacy and tolerability.15

2.3. Recommendations for omega-3 ethyl ester concentrate

The recommendations given by various associations/societies for the intake of Omega-3 ethyl ester concentrate following MI is as follows14,16,17;

| Scientific body | Recommendation |

|---|---|

| American Heart Association (AHA) | ▪ Consume approx.1 g of EPA + DHA per day |

| National Institute of Clinical Excellence (NICE) | ▪ For patients who have had an MI within 3 months and who are not achieving this, consider providing at least 1 g daily of omega-3-acid ethyl esters treatment licensed for secondary prevention post MI for up to 4 years (Grade B). |

| European Society of Cardiology (ESC) | ▪ Supplementation with 1 g of EPA + DHA per day |

2.4. Differences in n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) and other commercial fish oils

| Characteristics (non-prescription omega-3 fish oils preparations)18–20 | n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) |

|---|---|

| ▪ Crude fish oils produce peroxides and free radicals as primary oxidation products. This causes vascular impairment and proinflammatory effects which can lead to atherogenesis. ▪ Secondary oxidation produces aldehydes, furans, ketones etc. Accumulation of aldehydes causes ‘fish oil burping’ which can lead to bad compliance. |

n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) has the lowest intake of peroxides and aldehydes. |

| ▪ One of the factors used for assessing purity of fish oil preparation is peroxide value (PV). According to European Pharmacopeia PV should be ≤10, whereas according to Global Organization for EPA and DHA omega-3s (GOED) it should be ≤5. Most fish oils have a very high PV. | n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) has a PV < 3. |

| ▪ Fish is the largest source of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) and polychlorinated biphenyls (PCB) which increases the risk of insulin resistance, metabolic syndrome and hypertension. These impurities are measured as toxic equivalents (TE). | n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) being purified by the stripping process reduces these TE from 35 to 0.8 pg/g. |

3. Approved indications of n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg)

n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) has been approved by Food & Drug Administration (FDA) in United States for hypertriglyceridemia and in Europe and India as a prescription drug for secondary prevention of post-myocardial infarction (post MI) in addition to other standard therapy and endogenous hypertriglyceridemia.

4. Efficacy of n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) in reducing post MI mortality

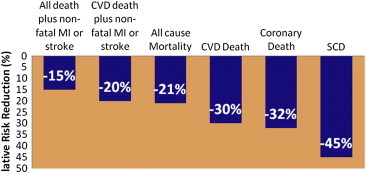

The GISSI-Prevenzione Study21 is the single largest study establishing the efficacy of n-3 acid ethyl esters of EPA & DHA in reducing cardiovascular mortality following MI. 11,324 patients surviving recent MI (≤3 months) were randomized to ‘standard therapy’ plus 1 g/day of highly purified omega-3 ethyl esters (of EPA and DHA) or vitamin E (α-tocopherol 300 mg/day), or both interventions for a period of 42 months. The mortality end points are shown in Fig. 1 [15% risk reduction for all-cause mortality plus non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke (p = 0.02), 20% risk reduction for CVD plus non-fatal MI and non-fatal stroke (p = 0.006) and 45% risk reduction in SCD (p = 0.0006)].

Fig. 1.

Mortality end points seen in GISSI-Prevenzione trial. (CVD–Cardiovascular disease). Data adapted from Marchioli R et al, 2002.22

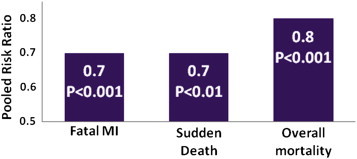

Bucher HC et al23 reviewed the effects of omega-3 PUFA on CHD in 11 trials. The dose for EPA varied from 0.3 to 6.0 g, whereas the dose for DHA ranged from 0.6 to 3.7 g for a period of 6–46 months. The results are shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Risk ratio seen in various cardiovascular outcomes following supplementation with ω-3 PUFA versus placebo. Data adapted from Bucher HC et al.23

5. Efficacy of n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) in reducing triglycerides

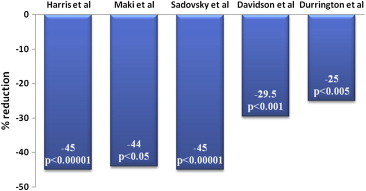

Various researchers (Harris et al,24 Sadovsky et al,25 Maki et al,26 Davidson et al,27 Durrington et al28 etc) have studied the effects of n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) with or without statins in patients with hypertriglyceridemia. All have shown that n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) was well tolerated and had a beneficial effect in terms of significant reduction in triglyceride levels (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3.

Percentage reduction in triglycerides with n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) therapy in different clinical studies. Data adapted from Harris et al,24 Sadovsky et al,25 Maki et al,26 Davidson et al,27 Durrington et al.28

According to the ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidemias, omega-3 ethyl esters should be considered in high risk cases and may also be considered for triglyceride lowering in combination with other therapies (Class IIa/level B).29

The recommended doses of EPA/DHA in patients with hypertriglyceridemia based on triglyceride levels ranges from 0.5 to 1 g for patients with borderline TG (150–199 mg/dL), 1–2 g for patients with high TG (200–499 mg/dL) and >2 g in very high TG (≥500 mg/dL). The American Heart Association recommends 2–4 g of EPA plus DHA per day, provided as capsules under a physician's care, for patients who need to lower their triglyceride level.30

6. The Indian consensus

Leading cardiologists from all over India came together to discuss the potential role of n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) in the management of post MI patients and those with hypertriglyceridemia. Their views and comments are summarized below.

6.1. Views on n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg)

-

▪

The advisory group agreed that n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) is not a regular omega-3 fatty acid, but is a highly purified concentrated ethyl esters of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) and a licensed prescription FDA drug recommended by ESC, AHA and NICE. It is free from most harmful impurities and side effects comparable to placebo in clinical trials. Commercial fish oil preparations have inadequate concentrations of EPA and DHA than the recommended doses, require multiple administrations, have large amount of oxidation products and contains toxin and contaminants (dioxins, polychlorinated biphenyls [PCBs], proteins with bound methyl mercury). The patients who are already taking some form of regular omega-3 fatty acid can be shifted to prescription n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) for better benefits as per label indications. However, they also felt that there is a need for more data generation on role of n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) in hypertriglyceridemia and post MI in Indian patients.

6.2. Consensus on use of n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) in preventing SCD following MI and in hypertriglyceridemia

-

▪

The group agreed that SCD is a major cause of mortality following post MI and current measures available for prevention are not adequate.

-

▪

Since n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) of EPA & DHA has anti-arrhythemic action, which may be one of the important factors to consider its use in post MI cases at a dose of 1 g per day and can be started immediately after MI and continued for at least 3–4 years.

-

▪

n-3 acid ethyl esters (90%) can be tried in sub-groups of post MI patients such as those with anterior wall infarct who are more prone for SCD, with a large infarct, at risk of developing arrhythmias or are candidates for ICD but cannot afford it, with low ejection fraction, diabetics, in patients with recurrent MI and in post MI patients with moderate hypertriglyceridemia (150–250 mg/dL) who usually do not require a specific triglyceride lowering therapy.

-

▪

The group agreed that the recommendation of ESC/EAS regarding the use of omega-3 fatty acid was strong enough with class IIa & level of evidence B & to be considered for use in the management of hypertriglyceridemia in Indian patients at a dose of 2–4 g per day as per AHA recommendation). It can be used in cases of severe hypertriglyceridemia (>500 mg/dL), in difficult to manage cases or in cases where patients cannot tolerate fibrates.

7. Summary

SCD is responsible for 10–35% of post MI deaths. Management is challenging and existing therapies are inadequate, costly or not widely available. Highly purified & concentrated omega-3 ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) has clinically proven benefits in improving post MI outcomes (significant 15% risk reduction for all-cause mortality, 20% risk reduction for CVD and 45% risk reduction in SCD in GISSI-Prevenzione trial) and in reducing hypertriglyceridemia, and hence, represent an interesting option adding to the treatment armamentarium in the secondary prevention after MI based on its anti-arrhythmogenic effects and also in reducing hypertriglyceridemia.

SCD is responsible for 10–35% of post MI deaths. Management is challenging and existing therapies are inadequate, costly or not widely available. Highly purified & concentrated omega-3 ethyl esters (90%) of EPA (460 mg) & DHA (380 mg) has clinically proven benefits in improving post MI outcomes (significant 15% risk reduction for all-cause mortality, 20% risk reduction for CVD and 45% risk reduction in SCD in GISSI-Prevenzione trial) and in reducing hypertriglyceridemia, and hence, represent an interesting option adding to the treatment armamentarium in the secondary prevention after MI based on its anti-arrhythmogenic effects and also in reducing hypertriglyceridemia.

8. Disclaimer

This consensus document has been developed to be of assistance to cardiologists and consulting physicians by providing guidance and information on the use of omega-3 ethyl esters in the management of hypertriglyceridemia and in patient's post MI. The recommendations mentioned should not be considered inclusive of all proper approaches or methods, or exclusive of others. The recommendations given here does not guarantee any specific outcome, nor do they establish a standard of care and hence are not intended to dictate the treatment of a particular patient. The physician's must rely on their own experience and knowledge to make diagnoses, to determine dosages and the best treatment for each individual patient and to take all appropriate safety precautions.

The authors or contributors do not assume any liability for any injury and/or damage to persons or property from any use or operation of any methods, products, instructions, nor ideas contained in the material herein.

For contraindications, warnings, precautions, etc., please look into the detailed “prescribing information.”

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Naik N., Rakesh Y., Rajnish J. Epidemiology of arrhythmias in India: how do we obtain reliable data? Curr Sci. 2009;97(3):411–415. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rao B.H., Sastry B.K.S., Korabathina R., Raju K.P. Sudden cardiac death after acute ST elevation myocardial infarction: insight from a developing country. Heart Asia. 2012:83–89. doi: 10.1136/heartasia-2012-010114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Madhavan S.R., Reddy S., Panuganti P.K. Epidemiology of sudden cardiac death in rural South India – insights from the Andhra Pradesh rural health initiative. Indian Pacing Electrophysiol J. 2011 Jul;11(4):93–102. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwok K.M., Lee K.L.F., Lau C.P., Tse H.F. Sudden cardiac death: prevention and treatment. Hong Kong Med J. 2003;9:357–362. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pires L.A., Lehmann M.H., Steinman R.T., Baga J.J., Schuger C.D. Sudden death in implantable cardioverter-defibrillator recipients: clinical context, arrhythmic events and device responses. J Am Coll Cardiol. 1999;33(1):24–32. doi: 10.1016/s0735-1097(98)00519-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Lehmann M.H., Thomas A., Nabih M., Participating Investigators Sudden death in recipients of first-generation implantable cardioverter-defibrillators: analysis of terminal events. J Interv Cardiol. 1994;7:487–503. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8183.1994.tb00485.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kapoor R., Patil U.K. Importance and production of omega-3 fatty acids from natural sources. Int Food Res J. 2011;18:493–499. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lavie C.J., Milani R.V., Mehra M.R., Ventura H.O. Omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and cardiovascular diseases. JACC. 2009;54(7):585–594. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2009.02.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kang J.X., Leaf A. Evidence that free polyunsaturated fatty acids modify Na+ channels by directly binding to the channel proteins. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1996;93:3542–3546. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.8.3542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Harper C.R., Jacobson T.A. The facts of life: the role of omega-3 fatty acids in the prevention of coronary heart disease. Arch Intern Med. 2001;161:2185–2192. doi: 10.1001/archinte.161.18.2185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehta J., Lawson D., Saldeen T.J. Reduction in plasminogen activator inhibitor-1 (PAI-1) with omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid (PUFA) intake. Am Heart J. 1988;116:1201–1206. doi: 10.1016/0002-8703(88)90440-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Jacobson T.A., Miller M., Schaefer E.J. Hypertriglyceridemia and cardiovascular risk reduction. Clin Ther. 2007;29(5):763–777. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.05.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.He K., Song Y., Daviglus M.L. Accumulated evidence on fish consumption and coronary heart disease mortality: a meta-analysis of cohort studies. Circulation. 2004;109(22):2705–2711. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.0000132503.19410.6B. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Graham I. European guidelines on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice: full text. Fourth Joint Task Force of the European Society of Cardiology and other societies on cardiovascular disease prevention in clinical practice (constituted by representatives of nine societies and by invited experts) Eur J Cardiovasc Prev Rehab. 2007;4(suppl 2):S1–S113. doi: 10.1097/01.hjr.0000277983.23934.c9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marchioli R. Treatment with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: results of GISSI-prevenzione trial. Eur Heart J Suppl. 2001;2(suppl D):D85–D97. doi: 10.1007/s11745-001-0694-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kris-Etherton P.M., Harris W.S., Appel L.J. Fish consumption, fish oil, omega-3 fatty acids, and cardiovascular disease. Circulation. 2002;106:2747–2757. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000038493.65177.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.der Werf Van, Ardissino D., Betriu A. Management of acute myocardial infarction in patients presenting with ST-segment elevation. Eur Heart J. 2003;24:28–66. doi: 10.1016/s0195-668x(02)00618-8. http://guidance.nice.org.uk/CG48/NICEGuidance/pdf/English. Accessed on Dec' 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dioxins and dioxin-like PCBs. In: Fish Oil Supplements. Available from: http://www.food.gov.uk/multimedia/pdfs/26diox.pdf. Accessed in December 2011.

- 19.Ruzzin J., Petersen R., Meugnier E. Persistent organic pollutant exposure leads to insulin resistance syndrome. Environ Health Perspect. 2010;118:465–471. doi: 10.1289/ehp.0901321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Everette C.J., Mainous A.G., Frithsen I.L. Association of polychlorinated biphenyls with hypertension in the 1999–2002 National health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environ Res. 2008;108:94–97. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2008.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.GISSI-Prevenzione Investigators Dietary supplementation with n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids and vitamin E after myocardial infarction: results of the GISSI-Prevenzione trial. Lancet. 1999;354:447–455. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marchioli R., Barzi F., Bomba E. Early protection against sudden death by n-3 polyunsaturated fatty acids after myocardial infarction: time-course analysis of the results of the Gruppo Italiano per lo Studio della Sopravvivenza nell'Infarto Miocardico (GISSI)-Prevenzione. Circulation. 2002;105:1897–1903. doi: 10.1161/01.cir.0000014682.14181.f2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bucher H.C., Hengstler P., Schindler C., Meier G. Polyunsaturated fatty acids in coronary heart disease: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Am J Med. 2002;112(4):298–304. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(01)01114-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Harris W.S., Ginsberg H.N., Arunakul N. Safety and efficacy of Omacor in severe hypertriglyceridemia. J Cardiovasc Risk. 1997 Oct–Dec;4(5–6):385–391. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sadovsky R., Kris-Etherton P. Prescription omega-3-acid ethyl esters for the treatment of very high triglycerides. Postgrad Med. 2009;121:145–153. doi: 10.3810/pgm.2009.07.2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maki K.C., McKenney J.M., Reeves M.S. Effects of adding prescription omega-3 acid ethyl esters to simvastatin (20 mg/day) on lipids and lipoprotein particles in men and women with mixed dyslipidemia. Am J Cardiol. 2008;102:429–433. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2008.03.078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Davidson M.H., Stein E.A., Bays H.E. Efficacy and tolerability of adding prescription omega-3 fatty acids 4 g/d to simvastatin 40 mg/d in hypertriglyceridemic patients: an 8 week, randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Clin Ther. 2007;29:1354–1367. doi: 10.1016/j.clinthera.2007.07.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Durrington P.N., Bhatnagar D., Mackness M.I. An omega-3 polyunsaturated fatty acid concentrate administered for one year decreased triglycerides in simvastatin treated patients with coronary heart disease and persisting hypertriglyceridaemia. Heart. 2001;85:544–548. doi: 10.1136/heart.85.5.544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Reiner Z., Catapano A.L., Backer G.D. ESC/EAS guidelines for the management of dyslipidaemias. The task force for the management of dyslipidaemias of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Atherosclerosis Society (EAS) Eur Heart J. 2011;32:1769–1818. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr158. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Miller M., Stone N.J., Ballantyne C. Triglycerides and cardiovascular disease: a scientific statement from the American heart Association. Circulation. 2011;123:2292–2333. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0b013e3182160726. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]