Abstract

Objective

The objective of this case series is to identify and define causes of failure of Szabo technique in rapid-exchange monorail system for ostial lesions.

Methods and results

From March 2009 to March 2011, 42 patients with an ostial lesion were treated percutaneously at our institution using Szabo technique in a monorail stent system. All patients received unfractionated heparin during intervention. Loading dose of clopidogrel, followed by clopidogrel and aspirin was administered. In 57% of patients, drug-eluting stents were used and in 42.8% patients bare metal stents. The stent was advanced over both wires, the target wire and the anchor wire. The anchor wire, which was passed through the proximal trailing strut of the stent helps to achieve precise stenting. The procedure was considered to be successful if stent was placed precisely covering the lesion and without stent loss or anchor wire prolapsing. Of the total 42 patients, the procedure was successful in 33, while failed in 9. Majority of failures were due to wire entanglement, which was fixed successfully in 3 cases by removing and reinserting the anchor wire. Out of other three failures, in one stent dislodgment occurred, stent could not cross the lesion in one and in another anchor wire got looped and prolapsed into target vessel.

Conclusion

This case series shows that the Szabo technique, in spite of some difficulties like wire entanglement, stent dislodgement and resistance during stent advancement, is a simple and feasible method for treating variety of ostial lesions precisely compared to conventional angioplasty.

Keywords: Sazbo, Ostial, Coronary, Stent, Drug-eluting

1. Introduction

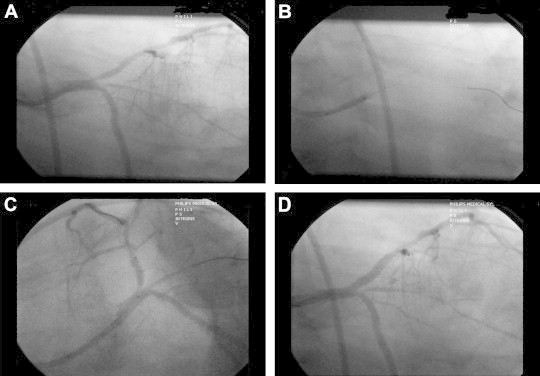

The accurate stenting of ostial lesions [an example is shown in Fig. 1A is often difficult due to their rigid, calcified and fibrotic nature, in addition to greater arterial wall thickness and elasticity which makes it more prone to recoil and difficult to stent. The precise placement of stent is, however, mandatory to avoid geographic miss and shifting of plaque to non-affected adjacent vessel, which is often difficult to achieve with conventional angiography.1,2 Szabo et al described a simple technique by using two guidewires the target wire and the anchor wire. In this technique, the stent advances over both wires. The anchor wire which passes through the proximal trailing strut of the stent helps to prevent further movement of the stent beyond the ostium and facilitates the precise stenting of ostium.3

Fig. 1.

A – Angiographic image shows ostial stenosis of the LAD which is suitable for Szabo's technique. Perfect ostial placement of stent is mandatory here to avoid missing the lesion and to avoid protrusion of stent into the LMCA. B – Use of the Szabo technique: target wire placed in LAD and anchor wire in Ramus. Stent was passed over both wires with anchor wire through the proximal cell of the stent. C – Stent was positioned exactly at ostium using the physical restraint created by the anchor wire. D – Angiographic image showing perfect deployment of the stent across the ostium with no protrusion of stent into the LMCA.

The monorail system which is also called as a rapid-exchange (RX) system has been used in the present case series. This case series describes difficulties and technical issues ensued during the treatment of an ostial lesion with Szabo technique in a monorail stent system.4 It also suggests the methods to eliminate errors of positioning to achieve precise deployment of stent.

2. Patients and methods

A total of 42 patients underwent percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) of ostial/bifurcation lesions (Median 0,1,0) by Szabo technique at our institution (Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences, Hyderabad) from March 2009 to March 2011. As part of the procedure, the unfractionated heparin (100 IU/kg) has been used to accomplish anticoagulation. All patients received loading dose of clopidogrel 300–600 mg, followed by clopidogrel 150 mg/day and aspirin 325 mg/day.

In our series, we have used monorail drug-eluting stents (DES) and bare metal stents (BMS) made up of stainless steel or cobalt chromium. BMS were used in patients with acute coronary syndromes and due to non-affordability issues.

The wiring of the target vessel was done after the advancement of the guiding catheter [Judkins Left (JL), Extra-back-up [(EBU) Medtronic, Minneapolis, MN] into the radial or femoral artery. Predilatation was done if required at the discretion of the Interventionalist. The anchor wire (Cougar, BMW, Allstar, Galeo and Regetta), [Table 1] was passed through the last cell of the stent by lifting the trailing edge with its hard end. The anchor wire was then placed in the non-affected adjacent vessel [Fig. 1B]. The stent was slowly advanced over both wires taking precaution that there was no entanglement of wires. If any resistance was felt during stent advancement into the target artery, the target wire was removed and re-inserted and this removed wire entanglement in most of the cases.

Table 1.

Stents and wires used in our case series.

| Variables |

N (%) (n = 42) |

|---|---|

| Target vessel | |

| LAD | 37 (88.10) |

| OM | 5 (11.90) |

| Total | 42 (100.00) |

| Szabo vessel | |

| DIAGONAL | 3 (7.14) |

| LCX | 24 (57.14) |

| OM | 1 (2.38) |

| RAMUS | 14 (33.33) |

| Total | 42 (100.00) |

| Anchor wire | |

| ALL STAR (Abbott Vascular) | 2 (4.76) |

| BMW (Abbott Vascular) | 21 (50.00) |

| COUGER (Medtronic) | 16 (38.10) |

| GALEO (Biotronik) | 2 (4.76) |

| REGETA (Cordis) | 1 (2.38) |

| Total | 42 (100.00) |

| Target Wire | |

| BMW (Abbott Vascular) | 24 (57.14) |

| COUGER (Medtronic) | 9 (21.43) |

| CROSS IT 200 (Abbott Vascular) | 1 (2.38) |

| CRUISER (Biotronik) | 2 (4.76) |

| GALEO (Biotronik) | 3 (7.14) |

| MIRACLE (Abbott Vascular) | 1 (2.38) |

| STB+ (Cordis) | 2 (4.76) |

| Total | 42 (100.00) |

| Guide | |

| 5FJL 3.0 (Medtronic) | 1 (2.38) |

| 6F EBU 3.0 (Medtronic) | 3 (7.14) |

| 6F EBU 3.5 (Medtronic) | 37 (88.10) |

| 6F JL 3.5 (Medtronic) | 1 (2.38) |

| Total | 42 (100.00) |

| Stent | |

| BIOMIME (Meril Life Sciences) | 3 (7.14) |

| CHRONO (CID-Italy) | 1 (2.38) |

| CYPHER (Cordis) | 1 (2.38) |

| DELIGHT (Unimark Remedies) | 1 (2.38) |

| ENDEAVOR (Medtronic) | 1 (2.38) |

| MAGIC (Eurocor) | 7 (16.67) |

| MEGAFLEX (Eurocor) | 1 (2.38) |

| TAXUS (Boston Scientific) | 4 (9.52) |

| TECNIC (Sorin Biomedica) | 1 (2.38) |

| XIENCE (Abbott Vascular) | 14 (33.33) |

| ZETA (Abbott Vascular) | 8 (19.05) |

| Total | 42 (100.00) |

Physical restrain from the anchor wire ensured appropriate coverage of the ostium [Fig. 1C]. Once the precise placement of ostial stent had been accomplished, the stent deployment was done as per the standard techniques. After the deployment of stent at nominal pressure, the anchor wire was removed carefully. Post dilation was done in most cases [Fig. 1D].

3. Results

Over 24 months of the study period, Szabo technique was performed in a total of 42 patients, with 35 (83%) males and 7 females (16.6%). Mean age of the study patients was 50 ± 13 years. The characteristics of the patient population are described in Table 2.

Table 2.

Patient characteristics.

| Characteristic | Szabo cases (n = 42) [Mean ± SD] |

|---|---|

| Male | 35(83.33%) |

| Age (year) | 50.17 ± 13.13 |

| Heart failure class III or IV | 1 (2.38%) |

| Current smoker | 16 (38.10%) |

| Diabetes mellitus | 11 (26.19%) |

| Hypertension | 21 (50.00%) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 11 (26.19%) |

| History of renal failure | 0 |

| Previous PCI | 1 (2.38%) |

| Previous CABG | 1 (2.38%) |

| Indications for procedure | |

| Acute coronary syndrome | 20 (47.62%) |

| Unstable angina pectoris | 10 (23.81%) |

| Myocardial infarction ≤7 days | 10 (23.81%) |

| Stable angina pectoris, no angina | 2 (4.76%) |

| Left ventricular ejection fraction (%) | |

| Fair | 1 (2.38%) |

| Good | 11 (26.19%) |

| Mild | 10 (23.81%) |

| Moderate | 16 (38.10%) |

| Severe | 4 (9.52%) |

| Target lesion vessel | |

| Native coronary artery | 42 (100.00%) |

| Saphenous vein graft | 0 |

| Left anterior descending | 37 (88.10%) |

| Left circumflex | 5 (11.90%) |

| Right | 0 |

| Procedural | |

| Number of lesions stented | 42 (100.00%) |

| Sirolimus – eluting stent used | 5 (11.90%) |

| Paclitaxel – eluting stent used | 4 (9.52%) |

| Everolimus | 14 (33.33%) |

| Zotarolimus | 1 (2.38%) |

| Bare metal stent (cobalt chromium) | 8 (19.05%) |

| Bare metal stent (stainless steel) | 10 (23.81%) |

| Stent length (mm) | 19.62 ± 5.69 |

| Stent Diameter (mm) | 3.13 ± 0.41 |

| Contrast used per patient (ml) | 167.38 ± 61.72 |

| Flouro time (radial approach) min | 13.06 ± 8.81 |

| Flouro time (femoral approach) min | 11.60 ± 7.73 |

The target vessel was left anterior descending (LAD) in 88% and the left circumflex – obtuse marginal coronary artery (LCX-OM) in 11.9% patients. Drug-eluting stents were implanted in 57% of patients and BMS in 42.8%. Further details are described in Tables 1 and 2.

The Szabo technique was successful in the majority of cases (33/42), while it failed in 9 cases. In an initial attempt to use the Szabo technique with monorail system, 6 out of 9 cases failed due to wire entanglement between the anchor wire and the target wire. The wire entanglement was fixed successfully in 3 cases by removing and reinserting the anchor wire after retrieving the stent outside. Out of other three failed cases, one case encountered stent dislodgment, one failed as stent could not cross the lesion and in another case anchored wire got looped and prolapsed into target vessel.

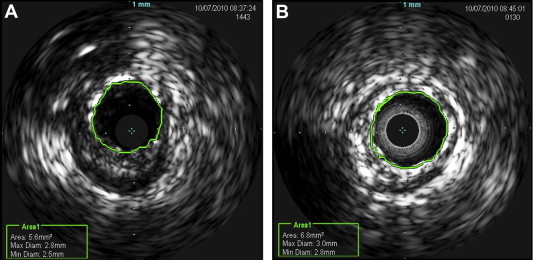

In one case intracoronary ultrasound (IVUS) [Fig. 2A and B] was used where 1–2 mm of stent struts was observed to extend proximal to the ostium.

Fig. 2.

A – Post-balloon dilatation IVUS image of the LAD ostium in a patient with severe ostial LAD disease. Predilatation was done before IVUS as the IVUS catheter did not pass prior to dilatation due to critical lesion. B – IVUS image of the ostial LAD after stenting using Szabo's technique. The stent is perfectly deployed.

4. Discussion

Treating ostial lesions has always been a difficult subset for Interventionalists. Methods like keeping second wire as marker or inflating low pressure balloon in other vessel are used to treat this subset.2 However, inaccuracies like geographic miss, bobbing or back and forth movement of the stent due to cardiac contractions makes it difficult to stent. Szabo et al described an effective technique to deal with problems of stenting. Kern et al1 demonstrated the feasibility of the technique. Applegate et al,4 Wong et al5 and Mohandes et al6 have described case series using Szabo technique. In the present case series all cases were done in RX system.

Table 3 outlines the failures we experienced.

Table 3.

Causes of failure of Szabo's technique.

| Cause of failure | Number of cases |

|---|---|

| Tortuosity of vessel | 1 |

| Stent dislodgement | 1 |

| Wire entanglement | 6 |

| Stent could not cross | 1 |

The first case failure occurred in a 43-year-old male patient who presented with acute anterior myocardial infarction with cardiogenic shock. His coronary angiogram showed proximal LAD with 99% stenosis with ostial involvement. Immediately after the lesion, there was an “S” shaped bend. The patient was taken up for primary angioplasty and stenting. Using thrombus extraction catheter, thrombosuction was done with lot of resistance. The BMW wire was passed into the LAD and Szabo wire (Cougar) into the LCX. The stent could cross the lesion but the LCX wire looped and prolapsed into LAD. This basically occurred due to tortuous lesion in proximal LAD immediately after the lesion. This case could have been successful if lesion was pre-dilated adequately before stent implantation, which was not done here as it is recommended to avoid predilatation, if possible, in primary angioplasty to reduce incidence of no-reflow.

The second case failed in a 24-year-old male patient with acute myocardial infarction taken up for rescue percutaneous coronary intervention. His coronary angiogram revealed 99% LAD stenosis immediately after large diagonal branch. The aim of using Szabo technique in this case was to avoid stenting across the diagonal branch. The lesion was not prepared for stenting. The target wire and the anchor wire were advanced into the LAD and diagonal branch, respectively. However, the anchor wire prolapsed into LAD. In an attempt to retrieve the flared stent into the guiding catheter, the stent got dislodged from the balloon and was hanging on the target wire. Later stent was snared from the femoral approach using the Amplatz gooseneck snare. It shows that anchored stent should not be pulled into guiding catheter as stent dislodgement is almost certain as in this case.

Six cases failed due to crisscrossing of wires. The chances of entanglement were considerably more in this system; this was dealt successfully in 3 cases by removing and reinserting the anchor wire. However, other 3 cases failed despite this. The problem of wire entanglement could be avoided to a large extent by single operator controlling lifting the distal end of stent with wire and conducting rest of the procedure.

Ninth case failed as stent could not cross the lesion.

From our experience the following considerations may be useful to achieve success and to avoid the commonly occurring complications:

-

1.

Lifting of proximal cell of stent with the distal end of the wire and stenting should be done by same operator to prevent crisscrossing to a large extent.

-

2.

It is recommended that the vessel should be prepared prior to stenting by adequate dilatation.

-

3.

It is suggested that the stent be never pushed into the vessel after anchoring. If resistance is felt before stent comes out completely of guiding catheter it could be due to crisscrossing of wires. This can be prevented by keeping the stent partly in guiding catheter and partly in the target vessel. The target wire in the stent is then to be withdrawn partially into the stent and the lesion is re-crossed with the target wire; the authors could carry out the procedure successfully in several cases by using this technique.

-

4.

Retrieving of anchored stent from the vessel onto the guiding catheter should be avoided to prevent stent dislodgement.

-

5.

It is recommended not to use hydrophilic anchor wire as the coating might get peeled away while crossing the lesion with stent.

-

6.

It is advisable to push the stent into the target vessel till a good bow-shaped configuration of anchor wire is achieved.

-

7.

BMS or DES can be used in Szabo technique without apparent complications during procedure.

-

8.

It is advisable to avoid Szabo technique if there is a distal tortuous in the vessel immediately after the lesion.

In conclusion, the present case series establishes the scope of Szabo technique to treat variety of ostial lesions. It is a good technique to avoid geographic miss and to decrease contrast usage in patients. In spite of some technical difficulties associated with Szabo technique, simplicity to perform makes it a potentially effective option for interventional cardiologists to deal with lesion subset with more precision and confidence.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Kern M., Ouellette D., Frianeza T. A new technique to anchor stents for exact placement in ostial stenoses: the stent tail wire or Szabo technique. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2006;68:901–906. doi: 10.1002/ccd.20613. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jokhi P., Curzen N. Percutaneous coronary intervention of ostial lesions. EuroIntervention. 2009;5:511–514. doi: 10.4244/eijv5i4a81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Szabo S., Abramowits B., Vaitkuts P.T. New technique for aorto-ostial stent placement (Abstr) Am J Cardiol. 2005;96:212 H. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Applegate R.J., Davis J.M., Leonard J.C. Treatment of ostial lesions using the Szabo technique: a case series. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2008;72:823–828. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wong P. Two years experience of a simple technique of precise ostial coronary stenting. Cathet Cardiovasc Intervent. 2008;72:331–334. doi: 10.1002/ccd.21558. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mohandes M., Krsticevic L., Guarinos J., Bonet A., Caminas A., Bardaji A. Success rate of Szabo technique in ostial coronary PCI: techniques, angiographic and IVUS findings. Iranian Cardiovasc Res J. Summer 2009;3:146–152. [Google Scholar]