Abstract

Objective: to examine the relationships between impairments in hearing and vision and mortality from all-causes and cardiovascular disease (CVD) among older people.

Design: population-based cohort study.

Participants: the study population included 4,926 Icelandic individuals, aged ≥67 years, 43.4% male, who completed vision and hearing examinations between 2002 and 2006 in the Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility-Reykjavik Study (AGES-RS) and were followed prospectively for mortality through 2009.

Methods: participants were classified as having ‘moderate or greater’ degree of impairment for vision only (VI), hearing only (HI), and both vision and hearing (dual sensory impairment, DSI). Cox proportional hazard regression, with age as the time scale, was used to calculate hazard ratios (HR) associated with impairment and mortality due to all-causes and specifically CVD after a median follow-up of 5.3 years.

Results: the prevalence of HI, VI and DSI were 25.4, 9.2 and 7.0%, respectively. After adjusting for age, significantly (P < 0.01) increased mortality from all causes, and CVD was observed for HI and DSI, especially among men. After further adjustment for established mortality risk factors, people with HI remained at higher risk for CVD mortality [HR: 1.70 (1.27–2.27)], whereas people with DSI remained at higher risk of all-cause mortality [HR: 1.43 (1.11–1.85)] and CVD mortality [HR: 1.78 (1.18–2.69)]. Mortality rates were significantly higher in men with HI and DSI and were elevated, although not significantly, among women with HI.

Conclusions: older men with HI or DSI had a greater risk of dying from any cause and particularly cardiovascular causes within a median 5-year follow-up. Women with hearing impairment had a non-significantly elevated risk. Vision impairment alone was not associated with increased mortality.

Keywords: AGES-Reykjavik study, hearing, vision, dual sensory impairment, all-cause mortality, cardiovascular disease mortality, older people

Introduction

Both vision and hearing loss are common age-related conditions, associated with poor health outcomes, including functional disability, depression and cognitive decline [1–9]. Numerous studies in diverse populations suggest sensory impairments (SI) are predictors of decreased survival, independent of other traditional mortality risk factors such as hypertension and diabetes [10–17]. However, data from the UK [18] and Australia [19] indicate that the association between visual impairment and mortality reflects concomitant morbidities. Similarly, an association between hearing impairment (HI) and mortality in the Blue Mountains Hearing study [20] became non-significant after adjustment for risk factors. Analyses linking data from the National Health Interview Survey with the National Death Index in the USA suggested that deaf participants experienced decreased survival, but this finding was attributed to their lower self-reported health status [21]. The joint effects of SI on health outcomes, including mortality risk, have not been investigated fully, particularly when compared with a single impairment [14].

As the population ages, the prevalence of hearing and visual impairments is expected to increase. This paper examines the risk of mortality associated with these impairments in the AGES-RS [22].

Methods

Study population

Participants of AGES-RS, a population-based study designed to investigate genetic and environmental risk factors of health, disease and disability in older adults, contributed to this analysis. The Icelandic Heart Association (IHA) initiated the Reykjavik Study in 1967, sampling 30,795 people born between 1907 and 1935 and living in Reykjavik, Iceland. From the original cohort, 11,549 were alive in 2002, and a random sample of 5,764 (mean age 77 years, range 67–98 years) participated in AGES-RS. Both vision and hearing examinations were completed by 4,944 (85.8%) participants between 2002 and 2006 [22]. Eighteen participants were excluded due to insufficient vision or hearing data for both eyes and both ears, resulting in 4,926 individuals for the current analysis.

The AGES-RS protocol was approved by the Icelandic National Bioethics Committee (VSN: 00-063), the Icelandic Data Protection Authority and by the Institutional Review Board for the National Institute on Aging, National Institutes of Health, USA. Written informed consent was acquired from all participants.

Vision and hearing examinations

During the baseline eye examination, presenting visual acuity, aided by current corrective lenses, if any, was measured in each eye separately using a table-top Nidek ARK 760A Autorefractor (Nidek Co. Ltd. Tokyo, Japan) with built-in acuity charts. Vision impairment (VI) was defined as a presenting visual acuity of 20/50 or worse in the better eye. Eyes that were blind were not excluded from this analysis.

As with vision, the baseline hearing examination followed a standardized protocol. Pure-tone air-conduction audiometry was conducted in a sound-treated booth using an Interacoustics AD229e microprocessor audiometer (Interacoustics A/S, DK-5610, Assens, Denmark) with standard TDH-39P supra-aural audiometric headphones or E.A.R. tone 3A insert earphones (MEDI, Benicia, CA, USA). Hearing thresholds at frequencies from 0.5 to 8 kHz (0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6 and 8 kHz with a repeat threshold test at 1 kHz for reliability) were measured in each ear. When significant inter-ear differences were found, re-tests were performed using insert earphones to maximise the inter-aural attenuation. ‘Moderate or greater’ HI was defined as at least 35 decibels (dB) hearing level (HL) for the pure-tone average of four frequencies (0.5, 1, 2 and 4 kHz) in the better ear. This definition corresponds to ‘disabling’ HI as defined by the Global Burden of Disease Hearing Loss Expert Group [23], and is the degree of hearing loss for which hearing aids are typically recommended.

Mortality outcome

Mortality status was ascertained by the IHA, with permission of the Icelandic Data Protection Authority, using the complete, adjudicated registry of deaths available from the Icelandic National Roster maintained by Statistics Iceland (http://www.statice.is/Statistics/Population/Births-and-deaths). All-cause and cardiovascular disease (CVD)-related mortality, assigned an ICD10 classification, was available for all deaths recorded through 31 December 2009.

Covariates

Demographic characteristics, health behaviours and medical history were considered as covariates. Education was dichotomized as secondary school graduation and higher versus less than secondary school completion. Smoking status was categorized as never, former or current smoker. The body mass index (BMI) was calculated as weight (kg) divided by height (meters) squared. Hypertension was defined as self-reported history of hypertension, use of antihypertensive drugs or blood pressure ≥140/90 mm Hg. Diabetes mellitus was defined as self-reported history of diabetes, use of glucose-modifying medications, or fasting blood glucose of ≥7.0 mmol/l. Blood samples were drawn after overnight fasting, and total cholesterol, high-density lipoprotein (HDL) cholesterol, triglycerides, glucose and HbA1c were measured in the IHA laboratory. HbA1c levels ≥6.5% were considered elevated. Depressive symptomology was defined as a score of 6 or greater on the 15-item Geriatric Depression Scale. Self-reported health status was dichotomized as good or poor based upon participants response to questions. Cognitive status was determined by professional consensus after reviewing results of cognitive examinations and dichotomized as normal or impaired. Falls during the past 12 months were based on self-report. Walking disability was defined as self-reported difficulty walking or the use of walking aids. A cardiovascular event was defined by report of a myocardial infarction, coronary artery bypass surgery or angioplasty.

Statistical methods

SI was classified into four mutually exclusive groups, no/mild/unilateral impairment, VI only, HI only or both VI and HI (dual sensory impairment, DSI). Participant characteristics were described using means and standard deviations for continuous variables and percentages and counts for categorical variables. Cox proportional hazards regression, adjusting for potential confounding risk factors, was used to calculate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% confidence intervals estimating risk of mortality for each impairment group. Since VI and HI increase with advancing age, as does mortality, the participant's age from their baseline examination was used as the time-scale for this analysis. The mortality status of all participants was determined as of 31 December 2009. Risk of mortality by the SI group was computed for participants of the same age, reported as HRs and graphically using Kaplan–Meier plots of survival past baseline examination. Since rates of sensory impairment and mortality differ for men and women, analyses were stratified by sex. Two-sided statistical tests and a 5% significance level were employed. Covariates retained in the analytic models are noted in table footnotes. All analyses were conducted using SAS version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC, USA).

Results

Among 4,926 participants, sensory impairment was present in 2,048 (41.6%) participants, of whom 1,250 (25.4%) had HI only, 455 (9.2%) VI only and 343 (7.0%) DSI. Participant characteristics are shown by the impairment group in Table 1. The mean age of the VI, HI and DSI groups was significantly higher compared with the unimpaired group. Among those with a given impairment, women were more likely than men to have VI (10.5 versus 7.6%, P = 0.10), whereas men were significantly more likely than women to have HI or DSI (29.9 versus 22.0%, P < 0.01 and 8.6 versus 5.7%, P < 0.01, respectively). After adjusting for age and sex, the impaired groups had significantly less education, poorer self-reported health, more depressive symptomology, cognitive impairment, walking disability and higher rates of diabetes.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics overall and by sensory impairment

| Baseline characteristic | Overall (n = 4,926) | Sensory impairment |

P-value* | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| None, mild or unilateral only (n = 2,878, 58.4%) | Vision only (n = 455, 9.2%) | Hearing only (n = 1,250, 25.4%) | Both hearing and vision (n = 343, 7.0%) | |||

| Mean age in years | 76.4 (5.5) | 74.5 (4.8) | 77.7 (4.9) | 78.9 (5.3) | 81.9 (5.0) | <0.01 |

| Age range in years | 66–96 | 66–93 | 67–91 | 66–96 | 69–96 | |

| Male | 43.1% (2,121) | 39.7% (1,142) | 35.6% (162) | 50.7% (634) | 53.4% (183) | <0.01 |

| Education level, completed secondary or more | 76.8% (3,755) | 79.9% (2,292) | 74.0% (335) | 73.2% (907) | 67.2% (221) | <0.01 |

| Marital status, married or living together | 60.2% (2,946) | 64.5% (1,850) | 56.1% (254) | 55.4% (688) | 46.7% (154) | 0.07 |

| Smoking status | ||||||

| Former | 44.9% (2,212) | 44.6% (1,282) | 41.5% (189) | 47.0% (587) | 44.9% (154) | 0.84 |

| Current | 12.1% (595) | 12.4% (357) | 13.2% (60) | 11.2% (140) | 11.1% (38) | 0.01 |

| Hypertension | 80.9% (3,982) | 78.4% (2,257) | 84.6% (385) | 83.3% (1,040) | 87.5% (300) | 0.35 |

| Mean DBP, mmHg | 74.0 (9.7) | 74.2 (9.6) | 73.8 (9.1) | 73.8 (9.7) | 72.4 (10.4) | 0.41 |

| Mean SBP, mmHg | 142.4 (20.3) | 141.5 (19.8) | 142.7 (20.3) | 143.7 (20.9) | 145.3 (21.9) | 0.99 |

| Mean BMI | 27.0 (4.4) | 27.3 (4.5) | 26.8 (4.4) | 26.8 (4.2) | 26.2 (4.2) | 0.52 |

| Self-reported health status, poor | 5.6% (274) | 4.7% (136) | 7.5% (34) | 6.1% (76) | 8.2% (28) | 0.04 |

| Depressive symptomology | 7.1% (332) | 5.9% (161) | 8.9% (38) | 8.3% (98) | 10.7% (35) | <0.01 |

| Cognitive status, impaired | 14.3% (695) | 7.8% (223) | 17.5% (78) | 21.5% (266) | 39.0% (128) | <0.01 |

| Walking disability | 17.7% (868) | 12.4% (356) | 22.0% (100) | 23.2% (290) | 35.7% (122) | <0.01 |

| Self-reported history of falls | 17.8% (877) | 16.3% (469) | 19.0% (86) | 19.7% (246) | 22.2% (76) | 0.11 |

| Mean number of medications | 4.1 (2.9) | 3.8 (2.7) | 4.1 (2.8) | 4.3 (3.0) | 4.8 (3.2) | 0.17 |

| Mean high-density lipoprotein cholesterol, mmol/l | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.4) | 1.6 (0.5) | 0.12 |

| Mean total cholesterol, mmol/l | 5.6 (1.2) | 5.7 (1.1) | 5.7 (1.1) | 5.6 (1.2) | 5.5 (1.2) | 0.96 |

| Mean glucose, mmol/l | 5.8 (1.2) | 5.8 (1.1) | 5.9 (1.7) | 5.8 (1.2) | 5.8 (1.1) | 0.07 |

| HbA1c ≥6.5% | 5.2% (238) | 4.6% (122) | 7.4% (31) | 5.8% (67) | 5.7% (18) | 0.05 |

| Baseline history by self-report | ||||||

| Angina | 14.5% (698) | 13.6% (384) | 14.3% (64) | 16.3% (198) | 15.9% (52) | 0.73 |

| Cancer | 15.0% (733) | 14.8% (423) | 14.6% (66) | 15.1% (187) | 16.7% (57) | 0.75 |

| CVD | 23.6% (1,160) | 21.5% (619) | 24.9% (113) | 26.1% (326) | 29.8% (102) | 0.55 |

| Diabetesa | 11.9% (584) | 10.8% (312) | 14.3% (65) | 12.9% (161) | 13.4% (46) | 0.04 |

| Record of clinical cardiovascular event | 15.5% (757) | 14.4% (410) | 17.2% (77) | 16.9% (210) | 17.7% (60) | 0.33 |

| Level of vision impairment (better eye)b,d | 0.85 | |||||

| None, mild or unilateral only | 83.8% (4,128) | 100% (2,878) | 0% (0) | 100% (1,250) | 0% (0) | |

| Moderate | 13.9% (686) | 0% (0) | 87.7% (399) | 0% (0) | 83.7% (287) | |

| Severe (includes blind) | 2.3% (112) | 0% (0) | 12.3% (56) | 0% (0) | 16.3% (56) | |

| Level of hearing impairment (better ear)c,d | 0.01 | |||||

| None, mild or unilateral only | 67.7% (3,333) | 100% (2,878) | 100% (455) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | |

| Moderate | 24.3% (1,198) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 77.4% (968) | 67.1% (230) | |

| Moderately severe | 6.6% (324) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 18.6% (233) | 26.5% (91) | |

| Severe (includes profound and deaf) | 1.4% (71) | 0% (0) | 0% (0) | 3.9% (49) | 6.4% (22) | |

| Mean pure tone audiometry valuee | 29.3 (13.7) | 21.5 (7.3) | 23.3 (7.3) | 44.7 (9.5) | 46.7 (10.6) | 0.08 |

| Hearing aid usee | 19.0% (934) | 4.0% (115) | 4.4% (20) | 49.9% (624) | 51.0% (175) | 0.61 |

| Tinnituse | 13.0% (639) | 11.7% (337) | 7.7% (35) | 18.4% (229) | 11.1% (38) | 0.05 |

| Frequent Tinnitus (daily or almost always)e | 10.8% (534) | 9.8% (281) | 5.9% (27) | 15.4% (193) | 9.6% (33) | 0.09 |

Data are presented as % (n) or mean (standard deviation).

aDiabetes mellitus was defined as the self-reported history of diabetes, use of glucose-modifying medications or fasting blood glucose ≥7.0 mmol/l.

bModerate VI is defined as a presenting visual acuity of 20/50, 20/60 or 20/80 and severe VI is defined as a presenting visual acuity of 20/200 or worse.

cModerate, moderately severe and severe or greater HI are defined as better ear PTA values between 35 and 49.9, 50–64.9 and 65+ dB HL, respectively. ‘Disabling’ HI is moderate HI or worse, according to the Global Burden of Disease Hearing Loss Expert Team definition [23].

dOnly compared non-zero impairment groups.

eOnly compared HI and DSI groups.

*Age and sex varied significantly across impairment groups (P < 0.01). For all other baseline characteristics, the P-value measures whether differences exist across the four sensory impairment groups after adjusting for age and sex.

Between their baseline examination and the end of the follow-up period (median follow-up, 5.3 years, range 3–7 years), 846 (17.2%) individuals died, of which 360 (42.6%) were attributed to CVD. Participants who died were significantly older (79.6 ± 5.7 versus 75.2 ± 4.9 years, P < 0.01) and more likely to be male (51.3 versus 39.8%, P < 0.01), a current or former smoker, report poor health, be cognitively impaired, have diabetes, a history of cancer, angina, CVD or cardiovascular event, higher HDL cholesterol levels and lower total cholesterol levels.

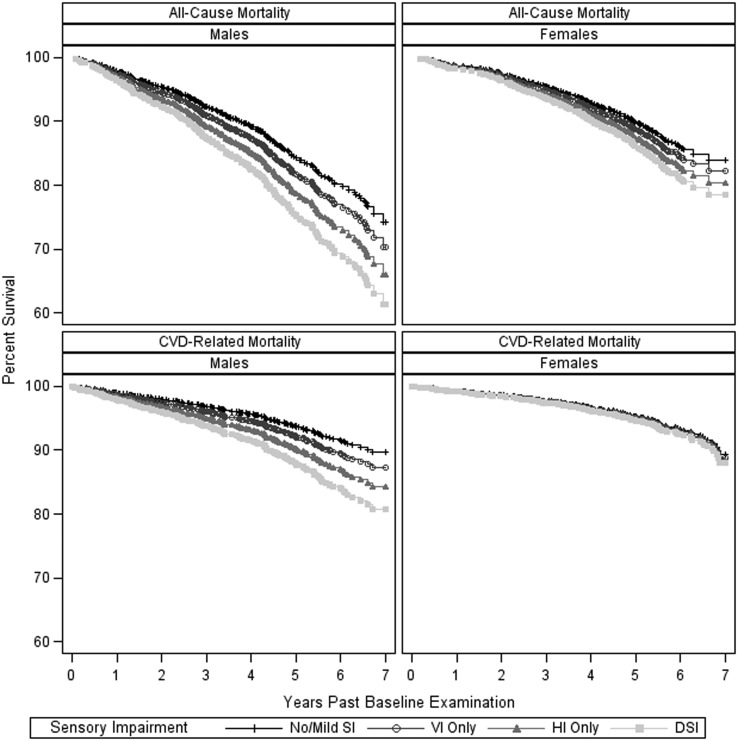

All-cause and CVD-related mortality rates among men and women were significantly different overall (both P < 0.01) and within each sensory impairment group, particularly the DSI group (all-cause: no SI, P < 0.01; VI, P = 0.03; HI, P < 0.01; DSI, P < 0.01; interaction between sex and SI, P = 0.09 and CVD: no SI, P = 0.09; VI, P = 0.08; HI, P = 0.01; DSI, P < 0.01; interaction between sex and SI, P = 0.07). Men were more impaired and more severely impaired in vision and hearing compared with women (results not shown). Adjusting for age differences, Figure 1 depicts mortality by sex for all-causes and CVD over the 7-year follow-up period for the four impairment groups.

Figure 1.

Kaplan–Meier plots for all-cause and CVD-related mortality rates by type of sensory impairment, stratified by sex and adjusted for age.

Compared with the unimpaired group, after adjustment for sex and age, participants with HI were at higher risk of CVD-related mortality [HR: 1.52 (95% CI: 1.17–1.97)], whereas participants with DSI were at higher risk of death from any cause [HR: 1.50 (95% CI: 1.19–1.90)] or from CVD [HR: 1.80 (95% CI: 1.24–2.61)], as shown in Table 2. After adjusting for established mortality risk factors, including smoking, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, self-reported health status, cognitive status, self-reported history of falls, total cholesterol, baseline CVD history and hearing aid use, DSI remained associated with all-cause mortality [HR: 1.43 (95% CI: 1.11–1.85)] and HI and DSI remained associated with CVD mortality [HRs: 1.70 (95% CI: 1.27–2.27) and 1.78 (95% CI: 1.18–2.69), respectively].

Table 2.

Hazards ratios and 95% confidence intervals (CI) for all-cause and CVD-related mortality by type of sensory impairment

| Participants at risk, n | All-cause mortality |

CVD-related mortality |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Deaths % (n) | Model 1a HR (95% CI) | Model 2b HR (95% CI) | Deaths % (n) | Model 1a HR (95% CI) | Model 2c HR (95% CI) | ||

| Overall | |||||||

| No/mild SI | 2,878 | 12.3% (354) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 4.7% (136) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| VI only | 455 | 17.4% (79) | 1.02 (0.79, 1.31) | 0.93 (0.72, 1.20) | 7.5% (34) | 1.22 (0.83, 1.79) | 1.10 (0.74, 1.65) |

| HI only | 1,250 | 23.2% (290) | 1.16 (0.98, 1.37) | 1.20 (1.00, 1.45) | 10.9% (136) | 1.52 (1.17, 1.97)* | 1.70 (1.27, 2.27)* |

| DSI | 343 | 35.9% (123) | 1.50 (1.19, 1.90)* | 1.43 (1.11, 1.85)* | 15.7% (54) | 1.80 (1.24, 2.61)* | 1.78 (1.18, 2.69)* |

| Men | |||||||

| No/mild SI | 1,142 | 15.4% (176) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 5.4% (62) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| VI only | 162 | 24.1% (39) | 1.04 (0.72, 1.50) | 0.90 (0.62, 1.32) | 10.5% (17) | 1.48 (0.84, 2.59) | 1.20 (0.66, 2.17) |

| HI only | 634 | 25.6% (162) | 1.14 (0.91, 1.44) | 1.20 (0.93, 1.55) | 11.8% (75) | 1.74 (1.21, 2.49)* | 1.93 (1.30, 2.87)* |

| DSI | 183 | 44.8% (82) | 1.88 (1.40, 2.52)* | 1.73 (1.25, 2.39)* | 20.8% (38) | 2.77 (1.75, 4.40)* | 2.65 (1.58, 4.44)* |

| Women | |||||||

| No/mild SI | 1,736 | 10.3% (178) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) | 4.3% (74) | 1 (reference) | 1 (reference) |

| VI only | 293 | 13.7% (40) | 1.00 (0.71, 1.41) | 0.94 (0.66, 1.33) | 5.8% (17) | 1.02 (0.60, 1.74) | 0.98 (0.56, 1.71) |

| HI only | 616 | 20.8% (128) | 1.19 (0.92, 1.53) | 1.23 (0.93, 1.64) | 9.9% (61) | 1.34 (0.92, 1.96) | 1.44 (0.93, 2.22) |

| DSI | 160 | 25.6% (41) | 1.03 (0.69, 1.54) | 1.07 (0.70, 1.64) | 10.0% (16) | 0.89 (0.45, 1.76) | 0.87 (0.42, 1.83) |

HR, hazard ratio; calculated by Cox proportional hazards regression models; CI, confidence interval; VI, vision impairment; HI, hearing impairment; DSI, vision and hearing impairment.

aAdjusted for age.

bAdjusted for age, smoking status, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, self-reported health status, cognitive status, self-reported history of falls, total cholesterol, baseline CVD history and hearing aid use.

cAdjusted for age, smoking status, BMI, hypertension, diabetes, systolic BP, self-reported health status, cognitive status, self-reported history of falls, history of angina, record of cardiovascular event and hearing aid use.

Additionally, all overall models also adjusted for sex.

*P-value < 0.01.

Compared with unimpaired men, after multivariable adjustment, men with DSI had increased risk of all-cause and CVD-related mortality [HRs: 1.73 (95% CI: 1.25–2.39) and 2.65 (95% CI: 1.58–4.44), respectively], whereas HI was significantly associated with CVD-related mortality [HR: 1.93 (95% CI: 1.30–2.87)] but not with all-cause mortality [HR: 1.20 (95% CI: 0.93–1.55)]. In women, associations between HI and all-cause or CVD-related mortality did not reach statistical significance [HRs: 1.23 (95% CI: 0.93–1.64) and 1.44 (95% CI: 0.93–2.22), respectively], and no associations were found between DSI and all-cause or CVD-related mortality.

Among people with HI or DSI, users of hearing aids were, on average, older and had more severe hearing loss compared with people without hearing aids; however, hearing aid users had significantly lower risk of all-cause mortality [HRs: 0.75 (95% CI: 0.58–0.96) for men and 0.67 (95% CI: 0.49–0.92) for women] and, among men, CVD-related mortality risk [HR: 0.63 (95% CI: 0.42–0.92)].

Discussion

This population-based study of community-dwelling older people found sensory impairment to be common and, for men with HI or DSI, associated with all-cause and CVD-related mortality. Whether sensory deficits in men are an indicator of ageing or frailty, physical manifestations resulting in reduced social competence or a reflection of other adverse health states is unclear. The adverse risk in men could not be attributed to smoking status, self-rated health, cognitive status, falls, walking disability or hearing aid use—all of which were observed to be important mortality risk factors in this study. The increase in mortality risk for men with HI and DSI was the main contributor to the significant overall results for men and women combined. These overall results confirm earlier reports of an association between DSI and increased risk of mortality in a combined sample of men and women [10, 15, 24]. Reuben et al. [5] did not find an association between DSI and mortality, but their sample was younger (aged 55–74 years) and had only 36 participants with DSI compared with the 343 participants ages 67 and older in the present study.

HRs of mortality in women with HI were generally above one, ranging between 1.2 and 1.4, suggesting a possibility of modestly elevated risk. However, these results did not reach statistical significance in this study.

The literature on HI and mortality is sparse [20, 21]. The Blue Mountains Hearing Study [20] reported an association between HI and mortality but concluded that walking disability, cognitive impairment and self-rated health mediated the relationship. In the current analysis, when walking disability, cognitive impairment and self-reported health were taken into account, they did not explain the impact of HI on mortality.

In our study VI was not significantly associated with mortality, consistent with findings from the Blue Mountains Eye Study [19] and the UK [18]. There was a high prevalence of HI in our cohort; however, the number with deficits solely in vision was relatively small. To assess mortality risk among all people with VI, we conducted a secondary analysis combining the VI and DSI groups and again found no association with mortality (results not shown). We cannot explain why our results for VI are different from other studies [25–30], but it is possible the older ages in our cohort and other differences in health states experienced by this population may be important.

A Japanese study of older adults aged 65+ years reported sex differences in HI and VI on risk of adverse health outcomes including mortality [12]. After covariate adjustment, increased risk of adverse health outcomes (including death) was reported for men with HI but not for women. No increased risk was reported for VI; DSI was not studied. After removing those using hearing aids, the increase in risk was not altered substantially. Hearing aid use was also considered in the current study. Men and women with hearing aids tended to be older and to have more severe hearing loss compared with others with HI but without hearing aids. However, men and women wearing hearing aids had a decreased risk of dying. We have no firm explanation for this, but we know a hearing aid can reduce the social isolation often experienced by those with HI and possibly the sensorineural stimulation from the hearing aid itself may be important.

The current study has several strengths including results based on a large cohort of older adults, a high participation rate, objective measurements for vision and hearing collected in a standardized manner, availability of a wide array of covariates, and a complete, adjudicated registry of deaths. The study ascertained mortality prospectively and without regard for impairment status. However, some limitations exist. The population is exclusively white, and the health profile of participants in this analysis was measured only once. Thus, increased mortality may result from an undocumented comorbid condition arising after the baseline examination. Finally, although unlikely, the possibility of selection bias, between those who completed the vision and hearing examinations and participants who did not, could have influenced the results.

In summary, older men with HI or DSI were at significantly increased risk of all-cause and CVD-related mortality. Use of hearing aids mitigated a portion of this increased risk. Health professionals delivering care to older people need to realize multiple sensory impairments are common and, particularly among men, may predict other adverse health conditions increasing risk of death. Regular assessment of sensory impairment and rehabilitation services targeted for those with decrements in hearing and vision in old age can promote enhanced quality of life, health and longevity.

Key points.

Men with HI and DSI had increased risk of all-cause or CVD-related mortality compared with men without any vision or HI.

Unlike men, women with HI had only slightly higher rates of mortality compared with women without any sensory impairment. Women with DSI were not at higher risk of mortality compared with women without sensory impairments.

VI was not associated with mortality from all-causes or CVD in men or in women.

Men and women who used hearing aids, although they were older and had more severe hearing loss, had significantly lower mortality risk compared with hearing impaired men and women who did not use hearing aids.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Institute on Aging (NIA) (contract number N01-AG-12100); the NIA Intramural Research Program (Z01-AG007380); the National Eye Institute (NEI) Intramural Research Program (ZIAEY000401); the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders (NIDCD) Division of Scientific Programs (IAA Y2-DC-1004-02); and with funding from Hjartavernd (Icelandic Heart Association) and the Althingi (Icelandic Parliament).

References

- 1.Salive ME, Guralnik J, Glynn RJ, et al. Association of visual impairment with mobility and physical function. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1994;42:287–92. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1994.tb01753.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.West SK, Munoz B, Rubin GS, et al. Function and visual impairment in a population-based study of older adults. The SEE Project. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 1997;38:72–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lin MY, Gutierrez PR, Stone KL, et al. Vision impairment and combined vision and hearing impairment predict cognitive and functional decline in older women. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:1996–2002. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52554.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rovner BW, Ganguli M. Depression and disability with impaired vision: the MoVIES project. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1998;46:617–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1998.tb01080.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Reuben DB, Mui S, Damesyn M, et al. The prognostic value of sensory impairment in older persons. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:930–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01286.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Keller BK, Morton JL, Thomas VS, et al. The effect of visual and hearing impairment on functional status. J Am Geriatr Soc. 1999;47:1319–25. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb07432.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Lin FR, Ferrucci L, Metter EJ, An Y, Zonderman AB, Resnick SM. Hearing loss and cognition in the Baltimore Longitudinal Study of Aging. Neuropsychology. 2011;25:763–70. doi: 10.1037/a0024238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dillon CF, Gu Q, Hoffman HJ, Ko CW. Vision, hearing, balance, and sensory impairment in Americans aged 70 years and over: United States, 1999–2006. NCHS Data Brief. 2010;31:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crews JE, Campbell VA. Vision impairment and hearing loss among community-dwelling older Americans: implications for health and functioning. Am J Public Health. 2004;94:823–9. doi: 10.2105/ajph.94.5.823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gopinath B, Schneider J, McMahon CM, Burlutsky G, Leeder SR, Mitchell P. Dual sensory impairment in older adults increases the risk of mortality: a population-based study. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e55054. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0055054. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0055054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Appollonio I, Carabellese C, Magni E, et al. Sensory impairments and mortality in an elderly population: a six year follow-up study. Age Ageing. 1995;24:30–6. doi: 10.1093/ageing/24.1.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Michikawa T, Nishiwaki Y, Kikuchi Y, et al. Gender-specific associations of vision and hearing impairments with adverse health outcomes in older Japanese: a population-based cohort study. BMC Geriatrics. 2009;9:50. doi: 10.1186/1471-2318-9-50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Engedal K. Mortality in the elderly: a three-year follow-up of an elderly community sample. Int J Geriat Psychiatry. 1996;11:467–71. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Schneider JM, Gopinath B, McMahon CM, Leeder SR, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Dual sensory impairment in older age. J Aging Health. 2011;23:1309–24. doi: 10.1177/0898264311408418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lam BL, Lee DJ, Gomez-Marin O, Zheng DD, Caban AJ. Concurrent visual and hearing impairment and risk of mortality: the National Health Interview Survey. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:95–101. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.1.95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Laforge RG, Spector WD, Sternberg J. The relationship of vision and hearing impairment to one-year mortality and functional decline. J Aging Health. 1992;4:126–48. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Agrawal N, Kalaivani M, Gupta SK, Misra P, Anand K, Pandav CS. Association of blindness and hearing impairment with mortality in a cohort of elderly persons in a rural area. Indian J Community Med. 2011;36:208–12. doi: 10.4103/0970-0218.86522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thiagarajan M, Evans JR, Smeeth L, et al. Cause-specific visual impairment and mortality: results from a population-based study of older people in the United Kingdom. Arch Ophthalmol. 2005;123:1397–403. doi: 10.1001/archopht.123.10.1397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Cugati S, Cumming RG, Smith W, Burlutsky G, Mitchell P, Wang JJ. Visual impairment, age-related macular degeneration, cataract, and long-term mortality. Arch Ophthalmol. 2007;125:917–24. doi: 10.1001/archopht.125.7.917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Karpa MJ, Gopinath B, Beath K, Rochtchina E, Cumming RG, Wang JJ, Mitchell P. Associations between hearing impairment and mortality risk in older persons: the Blue Mountains Hearing Study. Ann Epidemiol. 2010;20:452–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2010.03.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Barnett S, Franks P. Deafness and mortality: analyses of linked data from the National Health Interview Survey and National Death Index. Public Health Reports. 1999;114:330–6. doi: 10.1093/phr/114.4.330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Harris TB, Launer LJ, Eiriksdottir G, et al. Age, Gene/Environment Susceptibility–Reykjavik Study: multidisciplinary applied phenomics. Am J Epidemiol. 2007;165:1076–87. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwk115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Stevens G, Flaxman S, Brunskill E, et al. Global and regional hearing impairment prevalence: an analysis of 42 studies in 29 countries. Eur J Public Health. 2011 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckr176. Dec 24 (Epub ahead of print); doi:10.1093/eurpub/ckr176. First published online: December 24, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee DJ, Gomez-Marin O, Lam BL, et al. Severity of concurrent visual and hearing mortality: the 1986–1994 National Health Interview Survey. J Aging Health. 2007;19:382–96. doi: 10.1177/0898264307300174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wang JJ, Mitchell P, Simpson JM, et al. Visual impairment, age-related cataract, and mortality. Arch Ophthalmol. 2001;119:1186–90. doi: 10.1001/archopht.119.8.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Knudtson M, Klein BEK, Klein R. Age-related eye disease, visual impairment, and survival. The Beaver Dam Eye Study. Arch Ophthalmol. 2006;124:243–9. doi: 10.1001/archopht.124.2.243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McCarty CA, Nanjan MB, Taylor HR. Vision impairment predicts 5 year mortality. Br J Ophthalmol. 2001;85:322–6. doi: 10.1136/bjo.85.3.322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Freeman EE, Egleston BL, West SK, et al. Visual acuity change and mortality in older adults. Invest Ophthalmol Vis Sci. 2005;46:4040–5. doi: 10.1167/iovs.05-0687. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Foong AWP, Fong CW, Wong TY, et al. Visual acuity and mortality in a Chinese population. The Tanjong Pagar Study. Ophthalmology. 2008;115:802–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ophtha.2007.04.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cacciatore F, Abete P, Maggi S, et al. Disability and 6 year mortality in elderly populations. Role of visual impairment. Aging Clin Exp Res. 2004;16:382–8. doi: 10.1007/BF03324568. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]