Abstract

Background: home visits and telephone calls are two often used approaches in transitional care but their differential effects are unknown.

Objective: to examine the overall effects of a transitional care programme for discharged medical patients and the differential effects of telephone calls only.

Design: randomised controlled trial.

Setting: a regional hospital in Hong Kong.

Participants: patients discharged from medical units fitting the inclusion criteria (n = 610) were randomly assigned to: control (‘control’, n = 210), home visits with calls (‘home’, n = 196) and calls only (‘call’, n = 204).

Intervention: the home groups received alternative home visits and calls and the call groups calls only for 4 weeks. The control group received two placebo calls. The nurse case manager was supported by nursing students in delivering the interventions.

Results: the home visit group (after 4 weeks 10.7%, after 12 weeks 21.4%) and the call group (11.8, 20.6%) had lower readmission rates than the control group (17.6, 25.7%). Significance differences were detected in intention-to-treat (ITT) analysis for the home and intervention group (home and call combined) at 4 weeks. In the per-protocol analysis (PPA) results, significant differences were found in all groups at 4 weeks. There was significant improvement in quality of life, self-efficacy and satisfaction in both ITT and PPA for the study groups.

Conclusions: this study has found that bundled interventions involving both home visits and calls are more effective in reducing readmissions. Many of the transitional care programmes use all-qualified nurses, and this study reveals that a mixed skills model seems to bring about positive effects as well.

Keywords: transitional discharge support, hospital readmissions, home visits, telephone calls, older people

Introduction

In the last two decades, many studies have been conducted to test the effects of transitional discharge support. The main outcome variable of interest is hospital readmission. Other outcome measures such as quality of life and patient satisfaction have also been examined. Results of these transitional care programmes are mixed, partly due to their diverse and heterogeneous approaches, which make it difficult to draw firm conclusions [1, 2]. In his systematic review, Scott [3] categorised the intervention approaches into single component and integrated multicomponent interventions. In the single intervention category, only educational interventions with self-management approaches, post-discharge home visits and telephone follow-up were found to have significant effects on readmissions. As for the multicomponent interventions, those that assessed discharge needs, enhanced patient education and counseling, and conducted early follow-up of high-risk patients had significantly reduced use of hospital services. One might question whether more means better for the multicomponent programmes. Drewes et al. [4] conducted a systematic review including meta-regression analyses, finding that the number of components of chronic disease management had no association with the outcomes. Another systematic review could not identify a discrete single or bundled intervention that could reliably reduce rehospitalisations [5].

We know that many of the transitional discharge support programmes that reported positive outcomes are bundled with a combination of components, including patient assessment, and care management with an emphasis on patient education and self-empowerment. The nurse supported by a multidisciplinary team is usually the key person in these programmes, and home visits and telephone calls are the two most common approaches of care delivery [2, 3, 6, 7]. We do not know whether there is a differential effect between telephone calls and home visits within the bundled interventions. This study was therefore launched to examine the overall effects of a transitional care programme among a group of discharged patients with chronic diseases, and included a telephone call group only in order to examine its differential effects.

Methods

Study design

This was a randomised controlled trial with three groups. The intervention group had two arms, one receiving both home visits and telephone calls and the other receiving telephone calls only. The control group received placebo calls. All groups received usual care, which involved basic health advice, medication instructions and arrangements for outpatient follow-up.

Setting and subjects

The study took place in the medical department of an acute general hospital with 1700 beds in Hong Kong during the period from August 2010 to June 2012. We estimated the sample size based on a previous study using a similar transitional care programme for general medical patients, which resulted in a 21.7% improvement in their readmission rate [7]. A sample size of 182 for each group would be needed for a power of 80% and a 5% level of significance.

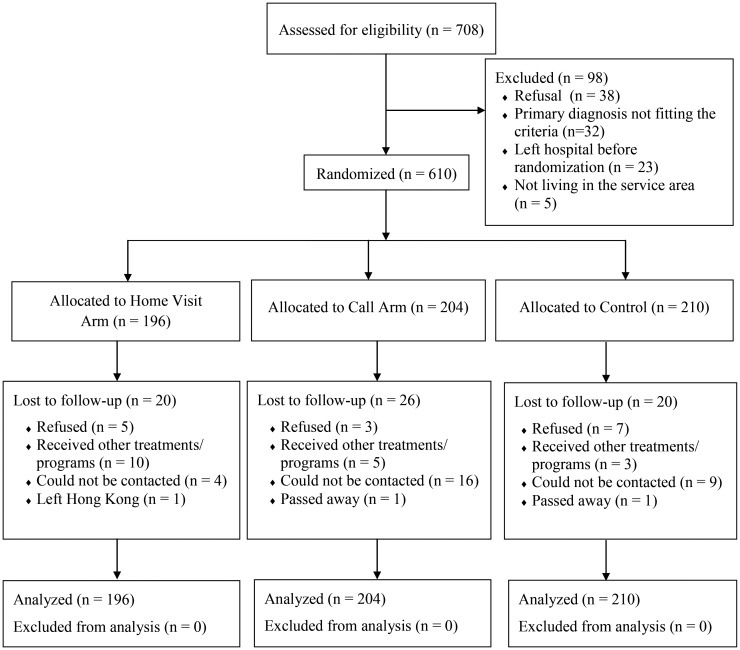

The random assignment was computer generated, placed in sealed envelopes and opened sequentially at the time of randomisation. After a subject was successfully recruited, the research assistant would call the site investigator, who had no knowledge of the identity of the subject, for random assignment. A total of 708 subjects were assessed for eligibility and 98 were excluded from the randomisation for various reasons (see Figure 1). The subject inclusion criteria were: (i) a primary diagnosis related to respiratory, diabetic, cardiac and renal conditions, (ii) MMSE >20, (iii) ability to speak Cantonese, (iv) living within the service area and (v) can be contacted by phone. The exclusion criteria were: (i) discharged to assisted care facilities, (ii) being followed up by an immediate designated disease management programme after discharge, (iii) inability to communicate and (iv) discharged for end-of-life care. This study targeted patients with chronic conditions because evidence suggested that they have post-discharge needs [6, 8] and the four chronic conditions selected were those that are most prevalent in this study population [8].

Figure 1.

Flow chart of subject progress through the phases of randomisation.

Placebo calls for the control group

The control group received two placebo calls which were social calls made by a research assistant not involved in data collection (see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix 1 for the call protocol).

Intervention

The intervention programme included a pre-discharge assessment and a 4-week post-discharge follow-up involving two home visits (Weeks 1 and 3) and two phone calls (Weeks 2 and 4). In each of the structured event, the nurse case manager (NCM) would conduct assessment and intervention based on the Omaha System [9] which addressed patients' needs in the domains of environment, psychosocial, physiological and health-related behaviour. Studies have shown the benefits of a comprehensive approach of post-discharge support among patients with chronic conditions [2, 3, 6, 8]. The home visits, telephone calls and referrals were governed by protocols to ensure a consistent approach of care delivery. The NCM was assisted by trained nursing students to provide part of the interventions. A previous study has shown that the use of trained volunteers to support NCMs in providing post-discharge care brought about positive effects [7]. The design of the programmes was based on the 4 Cs model proposed by Wong et al. [7]. The 4 Cs represent comprehensiveness, continuity, collaboration and coordination, which are key features that have proved to be effective for transitional care [2, 6, 7]. Comprehensiveness involves a holistic assessment of the patient's condition by the NCM. Continuity refers to regular, active and sustained follow-up care provided weekly. Collaboration is the partnering with the geriatrician to address patients' needs, such as medication or treatment plan review. The NCM set mutual goals with the patients so that they would take up an active role in managing one's own health. The coordination of different efforts was facilitated by the NCM. The intervention arrangement is as follows (see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix 1 for the intervention protocols).

Pre-discharge

Before patients were discharged, the NCM would conduct a pre-discharge assessment based on the Omaha System.

Post-discharge

The NCM applied the Omaha System to assess, intervene and implement the transitional care programme constructed with the same design for the home and call groups. Patients of the two intervention arms received the same quantity dose, weekly for 4 weeks, but the mode of delivery varied.

Home visit group

First week: the NCM conducted a home visit accompanied by nursing students; second week: the NCM made a telephone call; third week: the nursing students conducted a home visit; fourth week: the NCM made the closing call.

Call group

First week: the NCM made a telephone call; second week: the NCM called, or supervised nursing students making a telephone call; third week: the nursing students made a telephone call; fourth week: the NCM made the closing call.

The intervention period was 4 weeks because previous studies have shown that this duration is adequate for the dose–response to take effect [7, 10]. For the details of the preparation of the service providers, see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix 2.

Data collection

Data were collected at the time of discharge (O1), at 4 weeks after discharge when the intervention programme was completed (O2) and at 12 weeks (O3). The research assistants were trained and the inter-rater reliability ranged from 0.930 to 0.982 for the different instruments. Five percent of the data was selected for independent review to ensure data quality.

Measures

Baseline data

The baseline demographic and clinical data was collected at O1. The demographic data, age, gender, marital status, education, work status, accommodation, financial status and care-taking support, were collected from the interviews. The clinical data, MMSE, ADL, disease type and length of stay, were collected from pre-discharge documentation and patient charts. The entire set of baseline measures was validated and its reliability confirmed in previous studies [7].

Readmission data

The readmission data were captured at 28 days (4 weeks) and 84 days (12 weeks) post-discharge, respectively, to detect the immediate and sustained effects of the intervention. The data were extracted from the hospital information systems.

Data on secondary outcomes

The data at O1 were collected at randomisation in the hospital and the O2 and O3 data were collected at patients' home. The outcomes included quality of life, self-efficacy and satisfaction. We measured quality of life using the MOS 36-item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) [11]. The Hong Kong Chinese version was tested for its conceptual equivalence, with an overall Cronbach's alpha coefficient of 0.70 [12]. Self-efficacy was measured by the short version Chronic Disease Self-Efficacy Scale [13] with the construct validity and reliability (ICC = 0.91) of the translated Chinese version confirmed [14]. Satisfaction with care was measured using a 15-item questionnaire with confirmed validity and a test–retest reliability of 0.87 [7].

Data analysis

Baseline data among groups were examined by descriptive statistics, as recommended in the latest CONSORT guidelines [15]. Readmission rates among groups were compared using the logistic regression model by controlling the variables that were found to have significant association with hospital readmissions at univariate analysis (P < 0.05). Repeated measures analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was executed to investigate differences in quality of life, self-efficacy over time and satisfaction in the post-intervention period among groups. The analyses were conducted on an intention-to-treat (ITT) basis with the significance levels set at P < 0.05. Missing data were replaced by row mean methods based on individual scores [16].

Results

Baseline demographic and clinical data

There were 47.5% males and 52.5% females receiving no education (31.1%) or below primary level (45.2%). The median age was 76.5 and 96.5% were not in employment; 49.2% took care of themselves, whereas 32.1 and 10.8%, respectively, had their spouses and children taking care of them; 46.1% of the subjects had more than one disease type. The median length of hospital stay was 3 days. The median MMSE and ADL were 25 and 20, respectively (Table 1, see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix 3).

Table 1.

Logistic model on readmission rates

| Readmitted | No readmission | Walda | P-value | OR | 95% CI | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | |||||

| Within 28 days post-discharge | 5.00 | 0.082 | ||||

| Controlb | 37 (17.6) | 173 (82.4) | 1 | |||

| Home | 21 (10.7) | 175 (89.3) | 4.19 | 0.041* | 0.541 | (0.301–0.974) |

| Call | 24 (11.8) | 180 (88.2) | 2.66 | 0.103 | 0.624 | (0.354–1.100) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 79.0 (6.9) | 75.7 (7.1) | 7.748 | 0.005** | 1.056 | (1.016–1.097) |

| Marital status | 4.876 | 0.181 | ||||

| Singleb | 2 (15.4) | 11 (84.6) | 1 | |||

| Married | 35 (9.5) | 333 (90.5) | 0.195 | 0.659 | 0.701 | (0.145–3.388) |

| Divorced | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | 0.000 | 0.991 | 0.989 | (0.137–7.143) |

| Widow | 42 (20.1) | 167 (79.9) | 0.088 | 0.767 | 1.267 | (0.264–6.078) |

| Controlb | 37 (17.6) | 173 (82.4) | 1 | |||

| Intervention (Home and Call) | 45 (11.3) | 355 (88.7) | 4.84 | 0.028* | 0.583 | (0.360–0.943) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 79.0 (6.9) | 75.7 (7.1) | 7.599 | 0.006** | ||

| Marital status | 5.046 | 0.168 | ||||

| Singleb | 2 (15.4) | 11 (84.6) | 1 | |||

| Married | 35 (9.5) | 333 (90.5) | 0.184 | 0.668 | 0.709 | (0.147–3.422) |

| Divorced | 3 (15.0) | 17 (85.0) | 0.000 | 0.993 | 0.992 | (0.137–7.154) |

| Widow | 42 (20.1) | 167 (79.9) | 0.103 | 0.748 | 1.292 | (0.270–6.180) |

| Within 84 days post-discharge | 1.78 | 0.411 | ||||

| Controlb | 54 (25.7) | 156 (74.3) | 1 | |||

| Home | 42 (21.4) | 154 (78.6) | 1.10 | 0.294 | 0.778 | (0.486–1.244) |

| Call | 42 (20.6) | 162 (79.4) | 1.45 | 0.228 | 0.749 | (0.469–1.198) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 78.1 (7.3) | 75.6 (7.0) | 6.383 | 0.012* | 1.040 | (1.009–1.071) |

| Marital status | 6.177 | 0.103 | ||||

| Single | 3 (23.1) | 10 (76.9) | ||||

| Married | 65 (17.7) | 303 (82.3) | 0.073 | 0.787 | 0.832 | (0.219–3.165) |

| Divorced | 5 (25.0) | 15 (75.0) | 0.030 | 0.864 | 1.157 | (0.220–6.074) |

| Widow | 65 (31.1) | 144 (68.9) | 0.274 | 0.601 | 1.429 | (0.375–5.450) |

| Controlb | 54 (25.7) | 156 (74.3) | 1 | |||

| Intervention (Home and Call) | 84 (21.0) | 316 (79.0) | 1.76 | 0.185 | 0.763 | (0.512–1.138) |

| Age (mean, SD) | 78.1 (7.3) | 75.6 (7.0) | 6.501 | 0.011* | 1.040 | (1.009–1.072) |

| Marital status | 6.159 | 0.104 | ||||

| Single | 3 (23.1) | 10 (76.9) | 1 | |||

| Married | 65 (17.7) | 303 (82.3) | 0.075 | 0.784 | 0.830 | (0.218–3.155) |

| Divorced | 5 (25.0) | 15 (75.0) | 0.029 | 0.864 | 1.156 | (0.220–6.073) |

| Widow | 65 (31.1) | 144 (68.9) | 0.266 | 0.606 | 1.422 | (0.374–5.411) |

aLogistic regression adjusted by age and marital status.

bAs reference point: OR, odds ratio; *significant at P < 0.05; **significant at P < 0.01.

Readmission rates

The comparison of readmission rates using the logistic regression model adjusted by age and marital status is displayed in Table 1. The home visit group (10.7%, OR = 0.541, P = 0.041) had a significantly lower readmission rate than the control group (17.6%) but no significant difference was found in the call group (11.8%, OR = 0.624, P = 0.103) at 4 weeks. There was a significantly lower readmission rate of the intervention group (home and call combined) (11.3%, OR = 0.583, P = 0.028) when compared with the control group at 4 weeks. At 12 weeks, there was no difference between home/call and the control group (home 21.4%, call 20.6%, control group 25.7%).

Quality of life

Five of the eight domains in the SF36 measure showed significant differences among the three groups over time with O1 adjusted. They included physical functioning (F = 4.78, P = 0.009), role physical (F = 5.54, P = 0.004), vitality (F = 4.54, P = 0.011), social functioning (F = 7.89, P < 0.001) and mental health (F = 9.98, P < 0.001). However, only physical functioning (F = 4.13, P = 0.017) had significant group × time interaction effects (Table 1, see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix 4).

Self-efficacy and satisfaction

There was significant improvement in self-efficacy among the groups over time (F = 6.15, P = 0.002), but the interaction effect between group and time was not significant. As for satisfaction, the intervention groups had significantly higher satisfaction scores than the control group at O2 (F = 76.99, P < 0.001) (Table 1, see Supplementary data available in Age and Ageing online, Appendix 4).

Sensitivity analysis

We compared the ITT results with the per-protocol analysis (PPA) results for consistency. The trend of readmission rates was the same in both analyses, but unlike with the ITT, significant differences were detected in PPA analysis for home (5.7%, OR = 0.299, P = 0.002), call (7.3%, OR = 0.396, P = 0.009) and intervention (home and call combined) group (6.5%, OR = 0.347, P < 0.001) when compared with control (16.3%) at 4 weeks. At 12 weeks, significance difference was detected in the intervention group only (16.4%, OR = 0.611, P = 0.029 versus control 24.2%). As for quality of life, self-efficacy and satisfaction, results in ITT and PPA were similar.

Discussion

This study provides evidence to fill the knowledge gap in research on transitional discharge care, in two aspects. First, this study has detected the difference between the effectiveness of home visits with calls and that of telephone calls only in a bundled intervention programme. Secondly, this study initiated a transitional model of care that uses a skill mix, involving nursing students to support the nurse case manager. The use of assistants to support qualified providers is becoming more popular in healthcare delivery models, but there are few studies testing the effectiveness of the skill mix in transitional care.

Similar to our study (OR = 0.58, CI: 0.36–0.94), a systematic analysis revealed that groups with post-discharge support involving combined home visits and calls were less likely to be readmitted (RR = 0.75, CI: 0.64–0.88) [2]. Another systematic review showed no significant benefit of telephone support only (RR = 0.95, CI: 0.89–1.02) [17] and this concurs with our finding (OR = 0.62, CI: 0.35–1.10). Mere telephone calls are not potent enough to control readmission at a significant level [1, 17], whereas previous studies [18, 19] have shown that home visits alone are not effective in controlling readmissions and can be costly [20]. As confirmed in this study, the combination of home visits and calls tends to bring about significant effects not only in readmissions, but also quality of life [4, 7, 21], self-efficacy [7] and satisfaction [7, 22].

This study initiated a transitional model of care that used a skill mix with the nursing students supporting the nurse case managers. In the contemporary healthcare system facing resource constraints, the redesigning of the healthcare model to incorporate different skill mixes is advocated [23]. Support workers could help qualified health workers in the form of job substitution, by implementing some of the work requiring less competence but working towards the goals prescribed by professionals [23]. Well-trained care assistants allow qualified nurses to focus primarily on work that specifically requires the skill set of a registered nurse, such as assessment, prescription of intervention plan and case management [24, 25]. A systematic review revealed that support from a stroke liaison worker in the form of a healthcare worker or a volunteer had no effects on health outcomes [26]. Another study, on the other hand, found that trained volunteers were effective to support the nurse case manager to reduce hospital readmissions and enhance quality of life [7]. There is little empirical evidence to demonstrate the effectiveness of skill mix in post-discharge care [25] and this study adds to the literature.

Limitations

This study was conducted among patients with chronic diseases in a regional hospital in Hong Kong and results may not be able to be generalised to patients in other places. This study is an outcome research and has no data to inform which part of the intervention process that brings about the effects. This study has not included a cost analysis to link the utilisation outcome with cost.

Conclusion

This study has confirmed the effects of transitional discharge care on patients with chronic illnesses. It is the first to reveal that telephone calls alone may not be sufficient to bring about significant reductions in readmissions. Bundled interventions involving both home visits and calls are more beneficial for patients after discharge. Many of the transitional care programmes use all-qualified nurses, and this study reveals that a mixed skills model seems to produce positive effects as well.

Key points.

Home visits and telephone calls are two common approaches used in transitional care but their differential effects are unknown.

In a system facing resource constraints, skill mix using support workers to assist qualified health professionals is advocated.

This study has confirmed the effects of using bundled interventions involving both home visits and telephone calls.

A mixed skills model brings about positive effects in transitional care.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Funding

The work described in this paper was fully supported by a grant from the Research Grants Council of the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region, China (RGC Ref No 547909).

Supplementary data

Supplementary data mentioned in the text is available to subscribers in Age and Ageing online.

References

- 1.Mistiaen P, Poot E. Telephone follow-up, initiated by a hospital-based health professional, for postdischarge problems in patients discharged from hospital to home. 2008. pp. 1–126. The Cochrane Collaboration. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Phillips CO, Wright SM, Kern DE, et al. Comprehensive discharge planning with postdischarge support for older patients with congestive heart failure. JAMA. 2004;291:1358–67. doi: 10.1001/jama.291.11.1358. doi:10.1001/jama.291.11.1358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Scott IA. Preventing the rebound: improving care transition in hospital discharge process. Aust Health Rev. 2010;34:445–51. doi: 10.1071/AH09777. doi:10.1071/AH09777. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Drewes HW, Steuten LMG, Lemmens LC, et al. The effectiveness of chronic care management for heart failure: meta-regression analyses to explain the heterogeneity in outcomes. Health Serv Res. 2012;47:1926–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01396.x. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2012.01396.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hansen LO, Young RS, Hinami K, et al. Interventions to reduce 30-day rehospitalization: a systematic review. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:520–8. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-155-8-201110180-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mattke S, Seid M, Ma S. Evidence for the effect of disease management: is $1 billion a year a good investment? Am J Manag Care. 2007;13:670–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wong FKY, Ho MM, Yeung S. Effects of a health-social partnership transitional program on hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial. Soc Sci Med. 2011;73:960–9. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.036. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.06.036. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wong FKY, Ho M, Chiu I, et al. Factors contributing to hospital readmission in a Hong Kong regional hospital: a case-controlled study. Nur Res. 2002;51:40–9. doi: 10.1097/00006199-200201000-00007. doi:10.1097/00006199-200201000-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Martin K. The Omaha System: A Key to Practice, Documentation and Information Management (Reprinted 2nd edition) Omaha, NE: Health Connections Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Naylor MD, Brooten DA, Campbell RL, et al. Transitional care of older adults hospitalized with heart failure: a randomized, controlled trial. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2004;52:675–84. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2004.52202.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ware JE, Sherbourne CD. The MOS 36-item short form health survey (SF-36): conceptual framework and item selection. Med Care. 1992;30:473–83. doi:10.1097/00005650-199206000-00002. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lam C, Gandek B, Ren X, et al. Test of scaling assumptions and construct validity of the Chinese (HK) version of the SF-36 health survey. J Clin Epidemiol. 1998;51:1139–47. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(98)00105-x. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(98)00105-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lorig KR, Sobel DS, Ritter P, et al. Effects of a self-management program for patients with chronic diseases. Eff Clin Pract. 2001;4:256–62. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chow S, Wong FKY. The reliability and validity of the Chinese version of the short-form chronic disease self-efficacy scales of older adults. J Clin Nurs. 2013 doi: 10.1111/jocn.12298. DOI:10.1111/jocn.12298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Moher D, Hopewell S, Schulz KF, et al. CONSORT 2010 Explanation and elaboration: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ. 2010;340:c869. doi: 10.1136/bmj.c869. doi:10.1136/bmj.c869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Engels JM, Diehr P. Imputation of missing longitudinal data: a comparison of methods. J of Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:968–76. doi: 10.1016/s0895-4356(03)00170-7. doi:10.1016/S0895-4356(03)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clark R, Inglis SC, McAlister FA, et al. Telemonitoring or structured telephone support programmes for patients with chronic heart failure: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2007;334:942–5. doi: 10.1136/bmj.39156.536968.55. doi:10.1136/bmj.39156.536968.55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Wong FKY, Chow S, Chung L. Can home visits help reduce hospital readmissions? Randomized controlled trial. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62:585–95. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04631.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2008.04631.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Elkan R, Kendrick D, Dewey M, et al. Effectiveness of home based support for older people: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2001;323:1–9. doi: 10.1136/bmj.323.7315.719. doi:10.1136/bmj.323.7315.719. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stuck A, Kane RL. Whom do preventive home visits help? J Am Geriatr Soc. 2008;56:561–3. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01561.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2007.01561.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Courtney M, Edwards H, Chang A, et al. Fewer emergency readmissions and better quality of life for older adults at risk of hospital readmission: a randomized controlled trial to determine the effectiveness of a 24-week exercise and telephone follow-up program. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2009;57:395–402. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02138.x. doi:10.1111/j.1532-5415.2009.02138.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Riegel B, Carlson B, Kopp Z, et al. A Effect of a standardized nurse case-management telephone intervention on resource use in patients with chronic heart failure. Arch Intern Med. 2002;162:705–12. doi: 10.1001/archinte.162.6.705. doi:10.1001/archinte.162.6.705. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Manthorpe J, Martineau S, Moriarty J, et al. Support workers in social care in England: a scoping study. Health Soc Care Comm. 2010;18:316–24. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00910.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2010.00910.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Swick M, Doulaveris P, Christensen P. Model of care transformation: a health care system CNE's journey. Nurse Admin Q. 2012;36:314–9. doi: 10.1097/NAQ.0b013e318266f2ce. doi:10.1097/NAQ.0b013e318266f2ce. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Moran A, Nancarrow S, Enderby P, et al. Are we using support workers effectively? The relationship between patient and team characteristics and support worker utilisation in older people's community-based rehabilitation services in England. Health Soc Care Comm. 2012;20:537–49. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01065.x. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2524.2012.01065.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ellis G, Mant J, Langhorne P, et al. Stroke liaison workers for stroke patients and carers: an individual patient data meta-analysis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2010;5 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005066.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD005066.pub2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.