Abstract

Purpose

To report a case of pupillary block glaucoma associated with spontaneous crystalline lens subluxation into the anterior chamber in a 34-year-old man.

Methods

Dry vitrectomy was performed for securing enough retrolental space, and an intracapsular lens extraction was then performed via a corneolimbal incision. Additional endothelial cell damage was avoided with an injection of viscoelastics and gentle extraction of the crystalline lens. After deepening of the anterior chamber, scleral fixation of the intraocular lens was performed with an ab externo technique.

Results

Two months after the operation, a well-fixated intraocular lens was observed and intraocular pressure was stable. The postoperative corneal astigmatism was −3.5 dpt, and the patient had a best-corrected visual acuity of 20/25. Postoperative complications included decreased endothelial cell count and sector iris paralysis near the incision site.

Conclusions

An anteriorly subluxated crystalline lens can cause pupillary block glaucoma in healthy young adults. To prevent intraoperative complications, intracapsular lens extraction with dry vitrectomy can be a good surgical option. The endothelial cell density should be closely monitored after surgery.

Key words: Crystalline lens subluxation, Pupillary block glaucoma, Intracapsular lens extraction

Introduction

Anterior dislocation of the crystalline lens is uncommon, but can cause severe complications, such as secondary glaucoma, corneal edema and endothelial cell damage [1, 2]. Traumatic dislocation accounts for half of the causes [1]. Hereditary disorders, such as Marfan syndrome, homocystinuria and Weill-Marchesani syndrome, can lead to lens dislocation [3, 4]. Spontaneous dislocation of the crystalline lens is rarer than the other causes. We describe a successful case of intracapsular lens extraction in a patient with pupillary block glaucoma associated with a spontaneous crystalline lens subluxation into the anterior chamber of his left eye.

Case Report

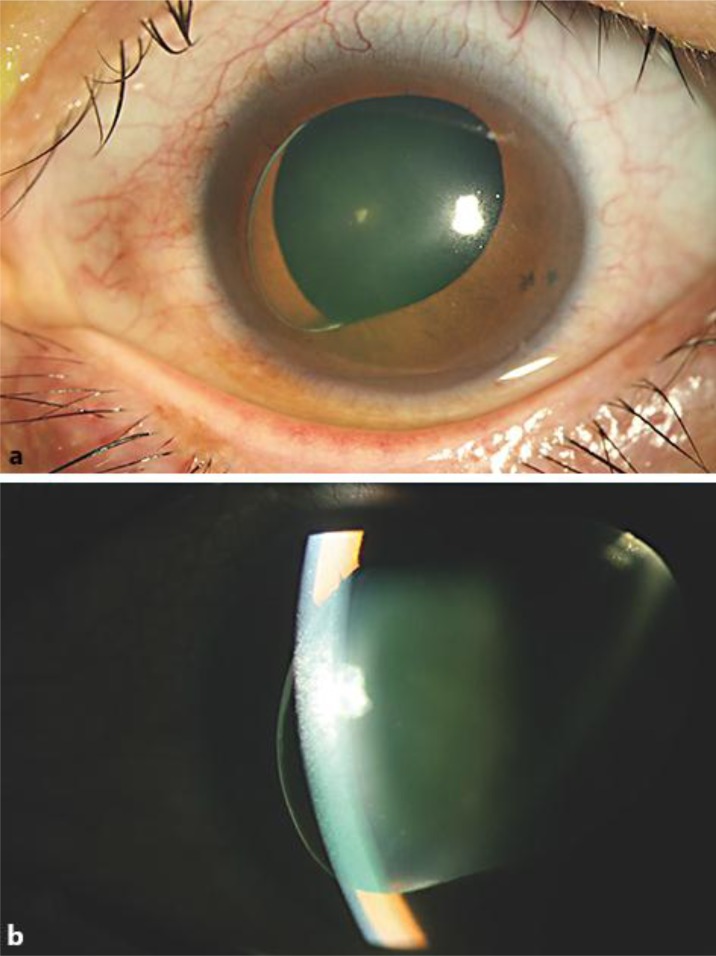

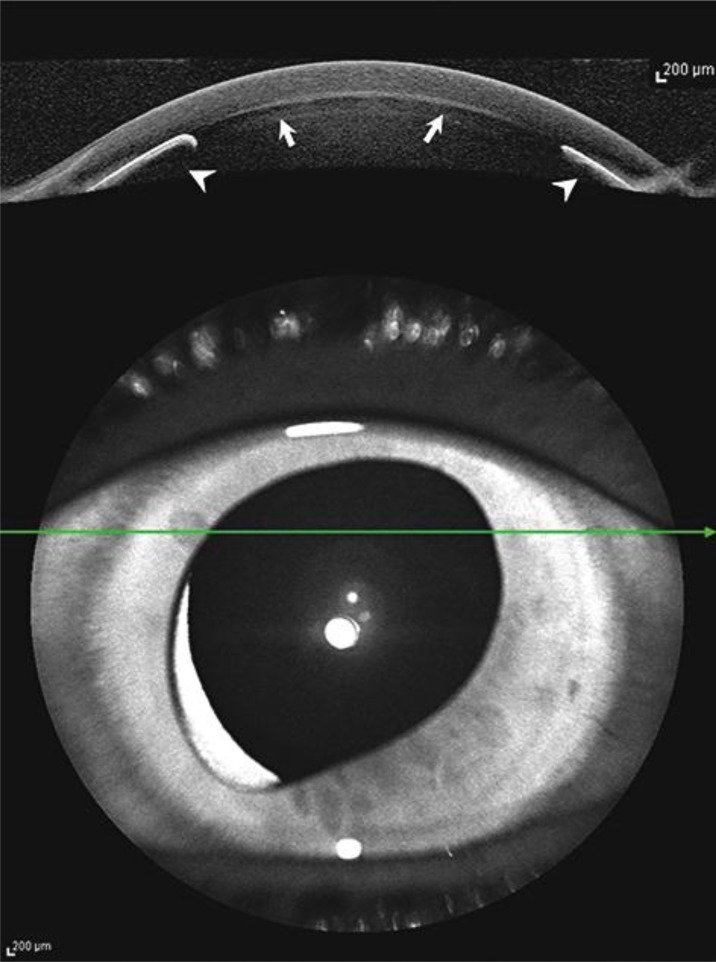

A healthy 34-year-old man presented with ocular pain and decreased vision in his left eye. Two years previously, he had been diagnosed with crystalline lens dislocation in his right eye. Lensectomy and intraocular lens scleral fixation had been performed at that time. Initial best-corrected visual acuity was 20/20 in his right eye and hand motion in his left eye. The intraocular pressure in his left eye was 42 mm Hg when measured with an applanation tonometer. Inspection revealed an edematous cornea and Descemet's membrane folds. The left pupil was irregular and anteriorly displaced, touching the endothelium of the cornea (fig. 1). There was no zonule around the anteriorly subluxated crystalline lens. Anterior segment optical coherence tomography revealed the partially subluxated lens, which was incarcerated in the pupil, and touching the endothelium of the cornea (fig. 2). The fundus displayed no significant finding.

Fig. 1.

a Lens partially subluxated into the anterior chamber. The crystalline lens is incarcerated in the pupil. b The whole corneal endothelium is touched by the iris and crystalline lens.

Fig. 2.

A subluxated lens (white arrows) and displaced iris (white arrowheads), touching the whole corneal endothelium, are detected by optical coherence tomography.

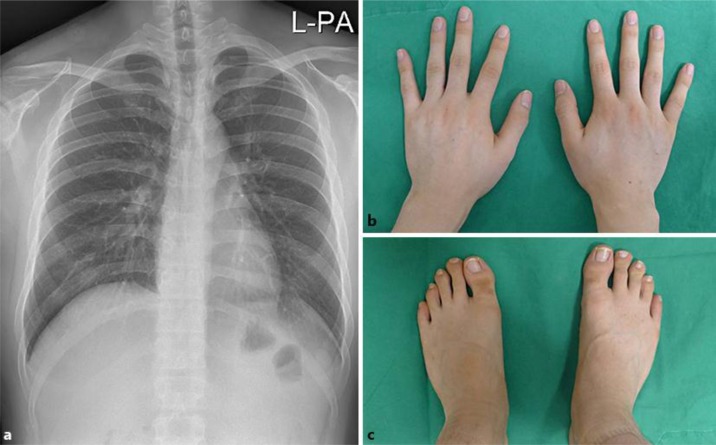

A physical examination and laboratory test were performed to evaluate the comorbidity. His height was 182 cm, weight 75 kg and arm-span 175 cm. Blood pressure was 110/70 mm Hg and pulse rate 80 bpm. There was no gross craniofacial abnormality or any skeletal abnormality on his spine and extremities (fig. 3). No valvular disease or aortic abnormality was found on electrocardiogram and echocardiogram. Complete blood count, renal function test, liver function test and routine urine analysis were within normal limits.

Fig. 3.

a Chest radiograph revealed normal cardiac and aortic shape. No abnormal lesion was visible in the parenchyma of either lung. Scoliosis of spine was not found. b, c There was no gross skeletal abnormality such as arachnodactyly or brachydactyly on hands or feet.

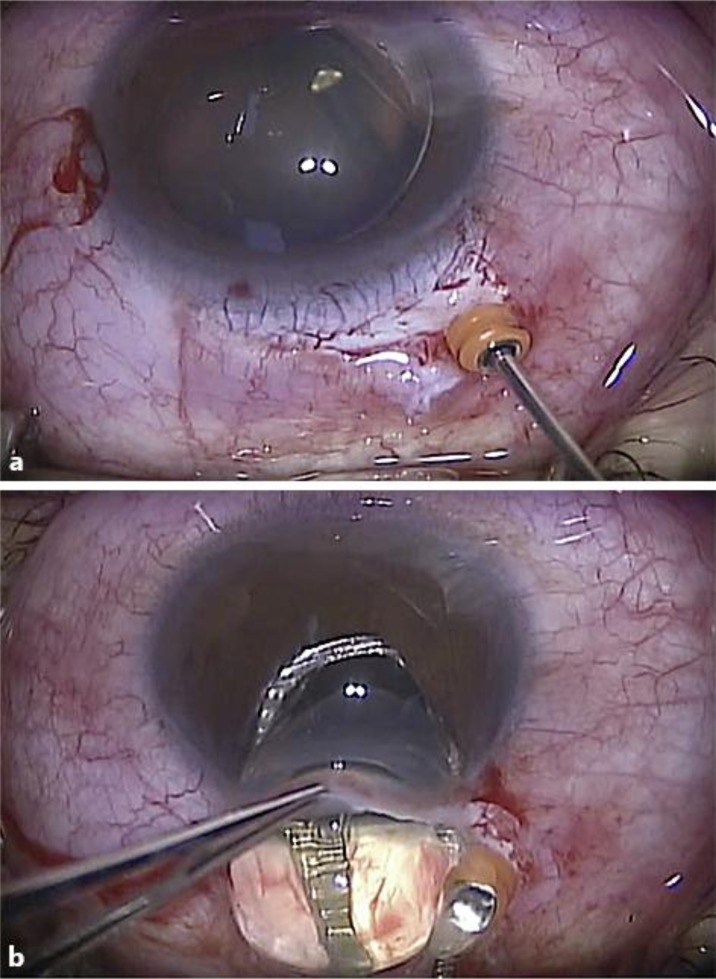

Mannitol was given intravenously to lower intraocular pressure. Pharmacological pupil dilatation was performed, and the patient lay on his back for repositioning of the lens. With the medical treatments not having any effect, we proceeded with a surgical intervention which consisted of partial pars plana dry vitrectomy, intracapsular lens extraction and intraocular lens scleral fixation. Corneal puncture was made at 3 o'clock and 10 o'clock, and viscoelastic materials (DisCoVisc, Alcon, Fort Worth, Tex., USA) were gently injected between the cornea and iris. Sclerotomy was performed with a 23-gauge microvitreoretinal blade 3 mm away from the limbus at the 11 o’ clock site; the vitreous cutter probe was inserted here, and the trocar was left. Partial pars plana dry vitrectomy was performed (fig. 4a). Viscoelastic materials were simultaneously injected into the anterior chamber. After getting enough space, a 6-mm corneoscleral incision was made. The whole lens was extracted with a lens spoon, without difficulty (fig. 4b). Herniated vitreous was removed with a vitreous cutter. After deepening of the anterior chamber, intraocular lens scleral fixation was performed with an ab externo approach.

Fig. 4.

a Dry vitrectomy was performed to get enough retrolental space and prevent sudden decreasing intraocular pressure after lens extraction. b Intracapsular lens extraction was performed with a lens spoon.

On the first postoperative day, severe stromal edema was found, and intraocular pressure was 18 mm Hg. For resolving the corneal edema, treatment with 5% sodium chloride solution was continued 4 times a day. Two months after the surgery, we observed a well-fixed intraocular lens and intraocular pressure was stable. The postoperative corneal astigmatism was −3.5 dtp and best-corrected visual acuity was 20/25. As a postoperative complication, decreased endothelial cell count was observed and sector iris paralysis was found near the incision site.

Discussion

There are several causes for anterior dislocation of the crystalline lens including trauma, Marfan syndrome, homocystinuria, spherophakia, retinitis pigmentosa and pseudoexfoliation syndrome as well as spontaneous causes [3, 4]. Pupillary block glaucoma, corneal endothelial damage and uveitis have been reported as complications [1, 2]. Unlike a posteriorly dislocated lens, an anteriorly dislocated lens should always be removed [1, 5].

We describe a clinical case of a crystalline lens that spontaneously subluxated into the anterior chamber. We could not analyze the FBN-1 gene because this genetic analysis was not available in our institution. However, our patient had no family history of congenital or connective tissue disease and no dietary methionine restriction or vitamin B6 supplementation. Furthermore, physical examination and radiological studies did not reveal any craniofacial, skeletal, valvular or aortic abnormality. Taken together, we think that this case was not associated with a congenital or connective tissue disorder, e.g. Marfan syndrome, homocysteinuria or Weill-Marchesani syndrome.

Several cases of anteriorly dislocated lens have been reported previously. Garza-Leon and de la Parra-Colín [2] reported on a medical procedure for the treatment of anterior dislocated lens. Jaffe et al. [6] suggested cryoextraction with a limbal incision and cryoprobe. Peyman et al. [7] suggested a standard vitrectomy and pars plana lensectomy. Choi et al. [1] and Seong et al. [8] described a successful case of anterior vitrectomy and intracapsular lensectomy, using the closed-chamber technique. Behndig [9] reported a case of anterior dislocation of the spherophakia, without snapping of the zonules, treated with phacoemulsification and in-the-bag intraocular lens implantation. All these cases concerned treatment for a crystalline lens that dislocated entirely into an anterior chamber, which meant there was enough space between the iris and cornea.

In our case, however, the crystalline lens was partially subluxated into the anterior chamber and was incarcerated in the pupil. The incarcerated lens had led to the pupillary block glaucoma and subsequent elevation of posterior pressure. Consequently, the iris was displaced anteriorly, with the whole corneal endothelium being touched by the subluxated lens and the displaced iris. There was no space between the cornea and the iris, so previously mentioned techniques or laser iridotomy could not be used on our patient.

Despite the potential for postoperative astigmatism, we had to choose a surgical technique, i.e. intracapsular lens extraction [10, 11]. In our case, due to not enough retrolental space, iris and lens injury were inevitable during creation of an incision with the blade. Therefore, partial pars plana dry vitrectomy was performed to prevent the iris and lens injury before the incision was made. For the maintenance of space between the iris and cornea, an infusion cannula was inserted through the corneal puncture site, and viscoelastic materials were injected into the anterior chamber gently and frequently. With these techniques, intraocular pressure suddenly decreasing after lens extraction through the 6-mm corneoscleral incision – which can lead to intraocular complications such as iris prolapse, intraocular hemorrhage or choroidal detachment – could be prevented. In addition, we could reduce the chance of corneal endothelial damage (which is caused by unavoidable lens rubbing) and retinal damage from dropped lens particles (which requires another surgical procedure, i.e. posterior vitrectomy) [12].

Two months after the operation, the intraocular pressure was stable and corneal opacity was absent. However, corneal endothelial cell density was markedly decreased. Considering that annual cell loss rate after cataract surgery approaches 2.5%, corneal decompensation would probably develop at a later date [13, 14].

In conclusion, an anteriorly subluxated crystalline lens can cause pupillary block glaucoma in healthy young adults. To prevent intraoperative complications, intracapsular lens extraction with a dry vitrectomy can be a good surgical option. Endothelial cell density should be closely monitored after surgery.

Acknowledgement

This work was supported by the Soonchunhyang University Research Fund.

References

- 1.Choi DY, Kim JG, Song BJ. Surgical management of crystalline lens dislocation into the anterior chamber with corneal touch and secondary glaucoma. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2004;30:718–721. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2003.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Garza-Leon M, de la Parra-Colín P. Medical treatment of crystalline lens dislocation into the anterior chamber in a patient with Marfan syndrome. Int Ophthalmol. 2012;32:585–587. doi: 10.1007/s10792-012-9592-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jarrett WH., II Dislocation of the lens. A study of 166 hospitalized cases. Arch Ophthalmol. 1967;78:289–296. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1967.00980030291006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kwon YA, Bae SH, Sohn YH. Bilateral spontaneous anterior lens dislocation in a retinitis pigmentosa patient. Korean J Ophthalmol. 2007;21:124–126. doi: 10.3341/kjo.2007.21.2.124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schafer S, Spraul CW, Lang GK. Spontaneous dislocation to the anterior chamber of a lens luxated in the vitreous body: two cases. Klin Monbl Augenheilkd. 2003;220:411–413. doi: 10.1055/s-2003-40275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jaffe NS, Jaffe MS, Jaffe GF. Cataract Surgery and Its Complications. ed 6. St Louis: Mosby-Year Book; 1997. pp. 201–212. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peyman GA, Raicchand M, Goldberg MF, Ritacca D. Management of subluxated and dislocated lenses with the vitrophage. Br J Ophthalmol. 1997;63:771–778. doi: 10.1136/bjo.63.11.771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seong M, Kim MJ, Tchah H. Argon laser iridotomy as a possible cause of anterior dislocation of a crystalline lens. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2009;35:190–192. doi: 10.1016/j.jcrs.2008.07.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Behndig A. Phacoemulsification in spherophakia with corneal touch. J Cataract Refract Surg. 2002;28:189–191. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(01)00904-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Steinert RF, Brint SF, White SM, Fine IH. Astigmatism after small incision cataract surgery: a prospective, randomized, multicenter comparison of 4- and 6.5-mm incisions. Ophthalmology. 1991;98:417–423. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kohnen T, Dick B, Jacobi KW. Comparison of induced astigmatism after temporal clear corneal tunnel incisions of different sizes. J Cataract Refract Surg. 1995;21:417–424. doi: 10.1016/s0886-3350(13)80532-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Netland KE, Martinez J, LaCour OJ, 3rd, Netland PA. Traumatic anterior lens dislocation: a case report. J Emerg Med. 1999;17:637–639. doi: 10.1016/s0736-4679(99)00052-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bourne WM, Nelson LR, Hodge DO. Continued endothelial cell loss ten years after lens implantation. Ophthalmology. 1994;101:1014–1022. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(94)31224-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kawashima M, Kawakita T, Shimazaki J. Complete spontaneous crystalline lens dislocation into the anterior chamber with severe corneal endothelial cell loss. Cornea. 2007;26:487–489. doi: 10.1097/ICO.0b013e3180303ae7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]