Abstract

Ras-catalyzed guanosine 5′ triphosphate (GTP) hydrolysis proceeds through a loose transition state as suggested in our previous study of 18O kinetic isotope effects (KIE) [Du, X. et al. ((2004)) Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 101, 8858–8863]. To probe the mechanisms of GTPase activation protein (GAP)-facilitated GTP hydrolysis reactions, we measured the 18O KIEs in GTP hydrolysis catalyzed by Ras in the presence of GAP334 or NF1333, the catalytic fragment of p120GAP or NF1. The KIEs in the leaving group oxygens (the β nonbridge and the β–γ bridge oxygens) reveal that chemistry is rate-limiting in GAP334-facilitated GTP hydrolysis but only partially rate-limiting in the NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis reaction. The KIEs in the γ nonbridge oxygens and the leaving group oxygens reveal that the GAP334 or NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis reaction proceeds through a loose transition state that is similar in nature to the transition state of the GTP hydrolysis catalyzed by Ras alone. However, the KIEs in the pro-S β, pro-R β, and β–γ oxygens suggest that charge increase on the β–γ bridge oxygen is more prominent in the transition states of GAP334-and NF1333-facilitated reactions than that catalyzed by the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras. The charge distribution on the two β nonbridge oxygens is also very asymmetric. The catalytic roles of active site residues were inferred from the effect of mutations on the reaction rate and KIEs. Our results suggest that the arginine finger of GAP and amide protons in the P-loop of Ras stabilize the negative charge on the β–γ bridge oxygen and the pro-S β nonbridge oxygen of a loose transition state, whereas Lys-16 of Ras and Mg2+ are only involved in substrate binding.

Ras is the prototypical member of the small G protein super-family that mediates diverse signaling pathways in eukaryotes (1, 2). Like other G proteins, Ras alternates between the guanosine 5′ diphosphate (GDP1)-bound inactive state and the GTP-bound active state. GTP-bound Ras is capable of binding to different effector proteins and thereby activating multiple signaling pathways. The intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras is very low, necessitating the down-regulation of Ras activity in vivo by GTPase activating proteins (GAPs) (3), including p120GAP (4) and neurofibromin 1(NF1) (5). Both GAPs increase the rate of GTP hydrolysis by more than 105-fold, from 10−4 s−1 to at least 8 s−1 (6, 7). Mutations in Ras that impair either intrinsic or GAP-facilitated GTPase activity leave Ras in a prolonged state of activation and were found in 30% of cancers (8). Mutations in NF1 are responsible for the pathogenesis of neurofibromatosis type 1 (9).

The chemical mechanism of Ras-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis, in particular the nature of the transition state in the intrinsic or GAP-facilitated GTPase reaction, has been the focus of considerable debate. The traditional view holds that the hydrolysis of a phosphate monoester with a good leaving group, of which GTP is one example, proceeds through a metaphosphate-like, loose transition state that features extensive cleavage to the bond between the phosphorus and the leaving oxygen but little or no bond formation between the phosphorus and the nucleophile (10–14). Recent computational studies suggest that metaphosphate is generated as a discrete intermediate in the reaction pathway before it is attacked by the nucleophilic water to generate phosphate (15, 16). An alternative, substrate-assisted, mechanism involves a proton transfer from the attacking water to GTP as a pre-equilibrium step (17–19). The hydroxide thus formed then attacks the γ phosphorus to form a phosphorane intermediate, which decays in the rate-limiting step to generate GDP and phosphate. Resolution of the mechanism is the key to the elucidation of the catalytic roles of the enzyme residues in GTP hydrolysis.

Infrared and Raman spectroscopic measurements clearly revealed that, upon binding to Ras, the Pβ–Oβ nonbridge bonds of GTP are weakened, but Pγ–Oγ nonbridge bonds are strengthened (20–22). If the distortion of the electronic structure of GTP by Ras represents destabilization of the ground-state in the direction of the transition state, it can be inferred that the transition state is loose. Indeed, our earlier studies revealed substantial 18O KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen and β nonbridge oxygens in Ras-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis, demonstrating substantial cleavage of Pγ–Oβγ bridge and Pβ–Oβ nonbridge bonds at the transition state (23). KIE in the two β nonbridge oxygens indicated that charge generated by the cleavage of Pγ–Oβγ bridge bond is delocalized into the two β nonbridge oxygen atoms through resonance structures. The KIE data, together with the crystal structures of Ras in complex with various GTP analogues (24, 25), provide insight into how Ras catalyzes GTP hydrolysis. Charge increase on the leaving group oxygens, namely, the β–γ bridge and the two β nonbridge oxygens, indicates that the interactions of Ras with the three leaving group oxygen atoms become stronger at the transition state and thereby afford preferential stabilization of the transition state. These interactions are mainly mediated by the P loop of Ras: the amide hydrogen of Gly-13 forms a short hydrogen bond with the β–γ bridge oxygen; the main chain NH groups of Val-14,Gly-15, and Lys-16, and the side chain of Lys-16 interact with the pro-S β nonbridge oxygen; the main chain NH of Ser-17 and Mg2+ interacts with the pro-R β oxygen (Figure 1). By contrast, interactions between the γ nonbridge oxygens and the Mg2+, the main chain NH groups of Thr-35 and Gly-60, and the side chain of Lys-16 are not expected to provide electrostatic stabilization of the transition state over the ground state.

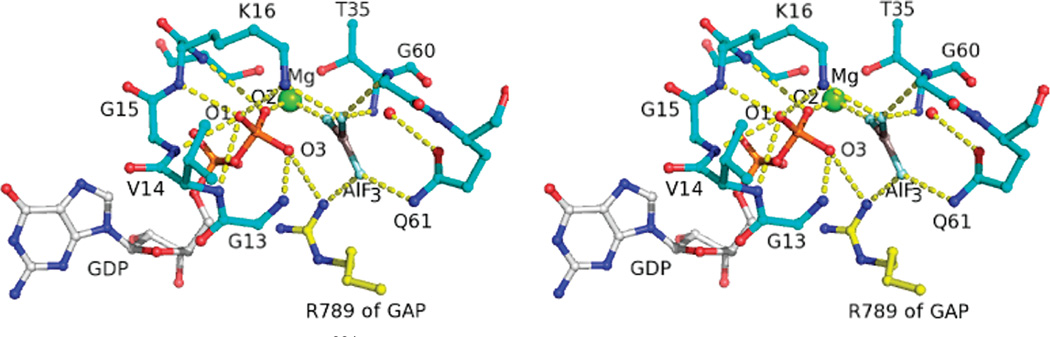

Figure 1.

Active site of Ras in complex with GAP334 and GDP · AlF3, a transition state analogue, in the crystal structure of Ras · GDP · AlF3 3 RasGAP (PDB ID 1WQ1). O1, O2, and O3 refer to the pro-S β nonbridge oxygen, the pro-R β nonbridge oxygen, and the β–γ bridge oxygen, respectively. The functional groups of Ras that contribute to interactions with the pro-S β nonbridge oxygen include the main chain NH groups of Val-14,Gly-15, andLys-16, as well as theNζ of Lys-16.The main chain NH of Ser-17 and Mg2+ interact with pro-Roxygen. The amide hydrogen of Gly-13 forms a strong hydrogen bond with the β–γ bridge oxygen. Interactions between Ras and γ nonbridge oxygens are realized by Mg2+, the main chain NH of Thr-35 andGly-60, the side chain of Gln-61, and the side chain of Lys-16.Arg-789 of GAP334 is positioned to interact with both the β–γ bridge oxygen and one γ nonbridge oxygen.

Structural, biochemical, and computational studies led to the notion that GAP334 facilitates the GTPase of Ras by stabilizing a catalytically competent conformation of Ras and by providing an arginine residue to electrostatically stabilize the transition state (13, 26–28). The crystal structure of Ras in complex with GAP334, a catalytic fragment of p120GAP, and GDP · AlF3, a transition state analogue (Figure 1), revealed that GAP334 stabilizes Switch II of Ras in a catalytically competent conformation (26). In this conformation, the main chain carbonyl oxygen of Thr-35 of Ras and the side chain oxygen atom of Gln-61 of Ras, which points away from the γ phosphoryl group in the absence of GAP334, form hydrogen bonds with the nucleophilic water and orient it for inline attack on the γ phosphorus. In addition, Arg-789 of GAP334, often referred to as the arginine finger, extends into the active site of Ras to interact directly with the β–γ bridge oxygen and one of the γ nonbridge oxygen atoms. The critical role of the arginine finger in catalysis was confirmed by biochemical and computational studies (27, 28). NF1333, the catalytic fragment of NF1, is structurally similar to GAP334 and also possesses a catalytic arginine finger (27, 29). Therefore, NF1 was proposed to facilitate GTP hydrolysis by a similar mechanism (29).

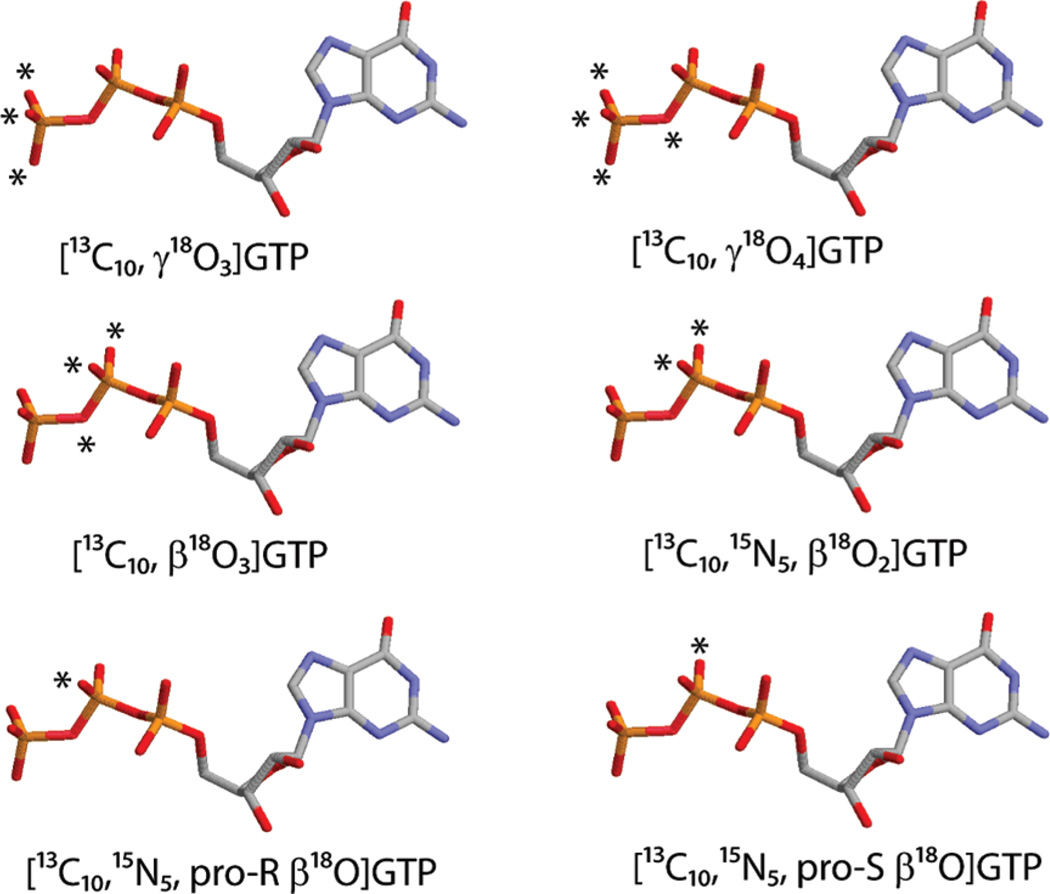

Here, we address the mechanism of GAP-facilitated GTP hydrolysis using 18O KIE as a probe of the transition state structures in these reactions. We have synthesized a suite of 18O-labeled GTP molecules (Figure 2) that allow the determination of the KIEs in the oxygen atoms at or geminal to the scissile bond. The KIE in γ18O3-labeling is equivalent to the secondary KIE in the hydrolysis of phosphate monoesters. The charge on the β–γ bridge oxygen due to the cleavage of Pγ–Oβγ bridge bond is delocalized into the two β nonbridge oxygens. The electron delocalization effectively increases the bond order of the β–γ bridge oxygen but decreases the bond order of the two β nonbridge oxygen atoms. Therefore, the KIE in β18O3, instead of the KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen alone, better reflects the extent of cleavage to the Pγ–Oβγ bridge at the transition state (23). The KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen is determined by the ratio of the KIE in β18O3 to that in β18O2 or by the ratio of KIE in γ18O4 to that in γ18O3.KIEs in the β–γ bridge, the pro-S β, and the pro-R β oxygens afford stereospecific probes of changes in bond orders and thereby the changes in the charges on these atoms at the transition state. Analysis of the kinetic behavior and KIEs of certain Ras mutants has enabled us to address the roles of the highly conserved residues, Lys-16 andGln-61, in the catalytic site of Ras. In experiments with an arginine finger mutant ofNF1333, we have assessed the role of the arginine finger in GAP-facilitated GTP hydrolysis.

Figure 2.

Double-labeled nucleotides used in this study. Carbon, nitrogen, oxygen, and phosphorus atoms are colored in silver, blue, yellow, and red, respectively. 18O-labels are indicated by *.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Materials

Guanine nucleotides uniformly labeled with 13C or 13C, 15N were purchased from Spectra Gases, Inc. The 13C enrichment is better than 99% as determined by electro-spray mass spectrometry. 13C-depleted GTP ([12C]GTP) was either purchased from Spectra Gases or synthesized as described earlier (30). The residual carbon isotope ratios in the [12C]GTP purchased or synthesized for this study were 0.23% and 0.09%, respectively. (97% enriched) was from Isotech. Other reagents for chemical synthesis were obtained from Sigma.

Synthesis of 18O,13C-labeled nucleotides

18O, 13C-labeled nucleotides were synthesized by coupling 18O-labeled phosphate or phosphate to guanine nucleotides uniformly labeled with 13C. The schemes for the synthesis of the six double-labeled nucleotides, [13C10, γ18O3]GTP, [13C10, γ18O4]GTP, [13C10, β18O3]GTP, [13C10,15N5, β18O2]GTP, [13C10,15N5, pro-S β18O]GTP, and [13C10,15N5, pro-R β18O] are provided as Supporting Information. The detailed procedures for the synthesis of [13C10, γ18O3] GTP, [13C10, γ18O4]GTP, [13C10, β18O3]GTP, and [13C10,15N5, β18O2]GTP were described earlier (23, 30). Electrospray mass spectrometry was used to deduce the 18O isotopic purity of 18O-and 13C-labeled GTP. The 18O enrichment level for [13C10, γ18O3] GTP, [13C10, γ18O4]GTP, [13C10, β18O3]GTP, [13C10,15N5, β18O2] GTP, [13C10,15N5, pro-Sβ18O]GTP, and [13C10,15N5, pro-R β18O] GTP were 96%, 94%, 96%, 94%, 95%, and 95%, respectively.

Synthesis of [13C10,15N5, pro-S β18O]GTP, and [13C10,15N5, pro-R β18O]GTP

The synthesis of [13C10,15N5, pro-S β18O]GTP and [13C10,15N5, pro-R β18O]GTP was carried out following the methods of Fritz Eckstein. R and S diastereomers of GTPβS were first synthesized (31). Sulfur in the R or S diastereomer was then substituted with 18O with the reversion of configuration, yielding [13C10,15N5, pro-S β18O]GTP, and [13C10,15N5, pro-R β18O]GTP, respectively (32). We used a modification of the protocol described by Connolly, et al. (32) to avoid the production of heavily bromated 18O GTP, as follows. GTPβS (1.5 mg) was mixed with 500 µL of GDP (80 mM) and 100 µL of dithiothreitol (300mM), and the solution was dried on a Speedvac. The residue was dissolved in 100 µL of and re-evaporated, and the step was repeated. Finally, the residue was dissolved in 200 µL of and 600 µL of N-bromosuccinimide (100 mM) in dry dioxane. After 5 min at room temperature, 100 µL of 1-mercaptoethanol was added to the solution. After 2min, 3mL of H2O was added, and the pH was adjusted to approximately 7.0 with 150 µL of triethylamine. The solution was then loaded onto a 5 mL HiTrap Q (GE Healthcare) column. GDP and GTP were separated by a 20 column volume, 0 to 1M gradient of ammonium acetate. The fraction containing GTP was collected and further purified on a 1 mL Hi Trap Q column. Ammonium acetate was removed afterward by lyophilization.

Protein Expression and Purification

A synthetic gene encoding residues 1 to 166 of human H-Ras was subcloned into a pET28 vector (33). The catalytic fragments of SOS1 (residues 564–1049) (34), mouse Cdc25 (residue 976–1260, Cdc25Mm285) (35), human NF1 (residue 1197–1528, NF1333) (36), and human p120GAP (residue 714–1097, GAP334) (6) were subcloned into pGEX vectors. Mutations in Ras and NF1333 were introduced using the QuickChange kit (Stratagene). His-tagged Ras and GST-fused Cdc25Mm285 were coexpressed in E. coli strain BL21 (DE3) and copurified as a complex through Ni-affinity, glutathione affinity, and ion-exchange column chromatography. Ras(K16A) in complex with Cdc25Mm285 was prepared similarly. Unlike other Ras mutants, Ras(Q61H) interacts with Cdc25Mm285 only weakly. When His-tagged Ras(Q61H) and GST-fused Cdc25Mm285 were coexpressed bacterially, the stoichiometric complex was not obtained following Ni-affinity and glutathione affinity chromatography. Instead, the Ras(Q61H)–SOS1 complex was prepared and used in this study. First, GST-fused SOS1 was retained on Glutathione-Sepharose beads. A tight complex of Ras(Q61H)-SOS1 is formed when excess Ni-affinity purified, His-tagged Ras(Q61H) was loaded onto the column. The complex was eluted with 10 mM glutathione and further purified by ion-exchange column chromatography. GAP334, NF1333, or NF1333(R1276A) was expressed in BL21(DE3) and purified by glutathione affinity and ion-exchange chromatography.

Steady State Condition for GTP Hydrolysis Catalyzed by Ras

A typical GTP hydrolysis reaction for Ras was carried out in 40 µL volume that contained 136 µM (11.3 mg/mL) Ras · Cdc25Mm285 complex, 1 mM GTP, 100 µM MgCl2, and 50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5. Reactions typically reached 50% completion after 32 h at 22 °C. Aliquots of 13 µL were taken, placed in a 100 °C heating block for 20 s to denature the proteins, and then frozen at −20 °C before IRMS analysis. The turnover rate for Ras-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis, determined by measurement of the reaction period during which half of the reactant is consumed, was 0.115 h−1 and was only one-sixth of the rate determined under single turnover conditions (20). Most of the reduction in rate can be ascribed to the inhibitory effect of Cdc25Mm285, which is expected to compete effectively with GTP for Ras and secure Ras in the Ras · Cdc25Mm285 complex (37). GDP also competes with GTP for Ras and product inhibition becomes significant even before the reaction is half-complete. On the basis of these considerations, it is estimated that about 20% to 25% of Ras existed in the Ras · GTP complex, while most of the Ras was in complex with Cdc25Mm285 at the beginning of the reaction.

Steady State Condition for GAP-Facilitated GTP Hydrolysis Reactions

Reactions in the presence of GAP334 were carried out in 30 µL volumes that contained 48 µM (4.0mg/mL) Ras · Cdc25Mm285 complex, 0.084 µM (0.0058 mg/mL) GAP334, 1 mM GTP, 25 µM MgCl2, and 50 mM HEPES at pH 7.5. Typically, a reaction reached 50% completion in 40 min. For other hydrolysis reactions, the same concentration of Ras or Ras mutant in complex with Cdc25Mm285 was used and the concentration of GAP was varied. The GAP concentration and the halftime of the reactions were as follows: 17 µM GAP334 and a t1/2 of 40 min for Ras(K16A)-GAP334; 0.087 µM NF1333 and a t1/2 of 60 min for Ras-NF1333; 4.3 µM NF1333 and a t1/2 of 40 min for Ras (K16A)-NF1333; and 17 µM NF1333(R1276A) and a t1/2 of 270 min for Ras-NF1333(R1276A). A typical experiment for Ras (Q61H)-NF1333 was carried out in 30 µL volume containing 51 µM (5.5 mg/mL) Ras(Q61H) · SOS1 complex and 67 µM (4.6 mg/mL) NF1333 and reached 30% completion in 240 min. The reactions for Ras-GAP334 and Ras-NF1333 were carried out in the presence of 25 µM MgCl2.Other reactions were carried out in the presence of 50 µM MgCl2.

Determination of KIEs

The method used to determine KIEs for GTP hydrolysis has been reported in detail (30) and is only briefly described here. An internal competition method was employed using 18O,13C-labeled GTP and 13C-depleted GTP. The double-labeled GTP is labeled with 18O at sites of mechanistic interest and with 13C at all carbon positions on the sugar and base of the nucleotide, while the 16O-nucleotide is depleted of 13C. The relative abundance of the labeled and unlabeled substrates or products is thereby reflected in the carbon isotope ratio (13C/12C) in GTP or GDP, which was measured using a LC-coupled IRMS. A KIE can be calculated from the change in the isotope ratio of the substrate GTP relative to that at the beginning of the reaction (Rs/R0), by the changes in the isotope ratio of the product GDP relative to that when hydrolysis is complete (Rp/R0), or by the difference between the isotope ratios in GDP and GTP (38). It was established that in our experimental system, the three methods give equivalent results, but the third method offers the best precision (30). Therefore, the changes in carbon isotope ratios of GDP and GTP (Rp/Rs) in the course of the reaction were used to calculate KIE according to eq 1. In a few cases, we were not able to accurately measure the isotope ratio of GDP, and the KIEs were calculated according to eq 2. Fractional reaction extent was calculated from mass 44 peak areas of GDP and GTP according to eq 3.

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

RESULTS

KIEs are reported in Table 1 for GTP hydrolysis catalyzed by Ras and Ras mutants, in the presence or absence of GAP334, NF1333, or the arginine finger mutant of NF1333. In addition to wild type proteins, Ras(K16A), Ras(Q61H), and NF1333(R1276A) were employed to probe the kinetic mechanism and the perturbation of the transition state by the indicated mutations. Ras and Ras mutants were purified as complexes with guanine nucleotide exchange factors, Cdc25Mm285 or SOS1, for several reasons: first, Ras proteins obtained in this way were free of GDP so that the isotope ratio of hydrolysis product (GDP) was not biased by the presence of residual, unlabeled GDP; second, Cdc25Mm285 and SOS1 accelerate GTP release and thereby reduce the external forward commitment for the reaction; third, the exchange factors accelerate product (GDP) release so that the steady state rate is not limited byproduct release; last, active Ras(K16A) can only be obtained when copurified with Cdc25Mm285. Six double-labeled nucleotides, [13C10, γ18O3]GTP, [13C10, γ18O4]GTP, [13C10, β18O3]GTP, [13C10,15N5, β18O2]GTP, [13C10,15N5, pro-S β18O]GTP, and [13C10,15N5, pro-R β18O], were used in this study (Figure 2). KIEs in 13C-labeling or 13C,15N-labeling were measured directly using 13C- or 13C,15N-labeled nucleotides. Corrections due to the incomplete 13C depletion in 12C-GTP and incomplete 18O-labeling in double-labeled GTP for the computation of the KIE in 18O-labeling were carried out according to the formulation of Hermes et al. (39).

Table 1.

KIEs in GTP Hydrolysis Reactions Catalyzed by Ras, GAP (GAP334 or NF1333), and Mutantsa

| labeling | Ras | Ras-GAP334 | Ras(K16A)-GAP334 | Ras-NF1333 | Ras(K16A)-NF1333 | Ras(Q61H)-NF1333 | Ras-NF1333(R1276A) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 13C | 1.0014 (8, 0.03%) | 1.0049 (11, 0.04%) | 1.0051 (8, 0.06%) | 1.0045 (11, 0.06%) | 1.0039 (20, 0.06%) | 1.0006 (6, 0.17%) | 1.0035 (12, 0.04%) |

| 13C, 15N | 1.0016 (6, 0.06%) | 1.0057 (9, 0.05%) | 1.0060 (15, 0.05%) | 1.0055 (9, 0.04%) | 1.0049 (9, 0.08%) | 1.0007 (6, 0.11%) | 1.0036 (8, 0.03%) |

| γ18O3b | 0.9994 (6, 0.09%) | 1.0012 (15, 0.11%) | 0.9989 (15, 0.17%) | 0.9992 (9, 0.09%) | 0.9983 (10, 0.08%) | 0.9991 (6, 0.19%) | 0.9994 (9, 0.05%) |

| γ18O4b | 1.0106 (6, 0.04%) | 1.0172 (15, 0.08%) | 1.0140 (14, 0.14%) | 1.0050 (9, 0.14%) | 1.0030 (6, 0.11%) | 1.0083 (6, 0.19%) | 1.0132 (9, 0.10%) |

| β18O3b | 1.0192 (5, 0.05%) | 1.0220 (21, 0.14%) | 1.0214 (17, 0.18%) | 1.0077 (17, 0.09%) | 1.0048 (11, 0.08%) | 1.0179 (6, 0.18%) | 1.0202 (9, 0.08%) |

| β18O2c | 1.0078 (6, 0.08%) | 1.0057 (9, 0.08%) | 1.0051 (9, 0.14%) | 1.0000 (9, 0.10%) | 0.9995 (7, 0.09%) | 1.0096 (6, 0.14%) | 1.0069 (9, 0.05%) |

| pro-S β18Oc | 1.0042 (6, 0.07%) | 1.0044 (9, 0.11%) | 1.0039 (9, 0.16%) | 1.0012 (9, 0.11%) | 1.0003 (7, 0.10%) | 1.0046 (6, 0.12%) | 1.0033 (9, 0.08%) |

| pro-R β18Oc | 1.0028 (6, 0.07%) | 1.0006 (8, 0.06%) | 1.0010 (8, 0.11%) | 0.9975 (9, 0.06%) | 0.9972 (9, 0.16%) | 1.0062 (6, 0.14%) | 0.9994 (9, 0.06%) |

| γ18O4/γ18O3d | 1.0112 (0.10%) | 1.0160 (0.14%) | 1.0151 (0.21%) | 1.0058 (0.17%) | 1.0047 (0.14%) | 1.0092 (0.27%) | 1.0138 (0.11%) |

| β18O3/β18O2e | 1.0113 (0.09%) | 1.0162 (0.15%) | 1.0162 (0.24%) | 1.0077 (0.13%) | 1.0053 (0.12%) | 1.0082 (0.22%) | 1.0132 (0.09%) |

| β–γ bridgef | 1.0113 | 1.0161 | 1.0157 | 1.0068 | 1.0050 | 1.0087 | 1.0135 |

| rate g | 0.115 h−1 | 2.5 s−1 | 0.012 s−1 | 1.6 s−1 | 0.048 s−1 | 0.00031 s−1 | 0.0018 s−1 |

Each KIE is an average with the number of determination and associated errors listed in parentheses. The following equation was utilized to correct for the incomplete 13C-depletion in [12C, 16O]GTP and incomplete 18O-labeling in double-labeled GTP 18(V/K) = WY/[A – (W – A)[(1 – B)Z/(BX)] – W(1 – Y)], where W = the observed isotope effect [KIE in 13,18(V/K) or 13,15,18(V/K)], A = the isotope effect in 13C- or 13C,15N-labeling, X = the fraction of 13C in the double-labeled GTP (0.99), Y = the fraction of 18O in double-labeled GTP (0.95), Z = the fraction of 13C in the [12C, 16O]GTP (0.23% or 0.09%), and B = the fraction of 13C- or 13C,15N-labeled GTP in the mixture of reactant (0.89% or 1.03% for Z of 0.23% or 0.09%, respectively).

The associated errors for the KIEs in γ18O3, γ18O4, or β18O3 are computed by Δ = [(Δ1)2+(Δ2)2]1/2, where Δ1 and Δ2 are the standard deviations in the corresponding KIEs in 13C, 18O-labeling, and 13C-labeling, respectively.

The associated errors for the KIEs in β18O2, pro-S β18O, or pro-R β18O are computed by Δ = [(Δ1)2+(Δ2)2]1/2, where Δ1 and Δ2 are the standard deviations in the corresponding KIEs in 13C, 13N, 18O-labeling, and 13C, 15N-labeling, respectively.

The KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen was computed as the ratio of the KIE in γ18O4 to the KIE in γ18O3.

The KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen was computed as the ratio of the KIE in β18O3 to the KIE in β18O2.

The average of KIEs in the β–γ bridge oxygen computed in the two ways.

The steady state rate for Ras, 0.5 [GTP]0/([Ras]xt1/2); steady state rates for GAP-facilitated reactions, 0.5 [GTP]0/([GAP]xt1/2).

DISCUSSION

Kinetic Mechanisms and Reaction Rates for GAP-Facilitated GTP Hydrolysis

The minimal kinetic mechanism for a GAP334- or NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis reaction can be described by eq 4.

| (4) |

The reaction may be considered as a system with GAP as the enzyme and Ras · GTP as the substrate. The steady where state rate takes the form of Michaelis–Menten equation as in eq 5.

| (5) |

Under saturating or limiting concentration of Ras · GTP, the reaction rate is given by

| (6) |

| (7) |

respectively. In a typical experiment with GAP, the concentration of Ras · GTP is estimated to be around 12 µM (~25% of total Ras; Materials and Methods). The values of Km for GAP334 and NF1333 were reported to be 4.8 µM and 0.13 µM, respectively (7, 27). Therefore, the steady state rates for GAP334-facilitated or NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis can be approximated by eq 6.

Practical Considerations in the Interpretation of KIEs

A KIE is defined as a ratio of the reaction rate of the substrate containing light isotopes of the atoms of interest to that of the substrate in which the corresponding atoms are substituted by a heavier isotope (40). Isotopic substitution lowers the vibrational energy levels of a molecule to an extent that depends on geometry and bond strength. If bond order decreases at the transition state, isotopic substitution lowers the zero point vibrational energy of the ground-state more than that of the transition state, which causes an increase in the activation energy for the heavier molecule and results in a normal isotope effect (> 1). In the opposite case where the bond order in the transition state increases, the activation energy is lower for the heavier isotopomer, and an inverse isotope effect (< 1) is observed. If the labeled atoms are involved in reaction coordinates, there is also a normal (> 1) contribution to the isotope effect from the reaction coordinate. The magnitudes of the KIEs often permit qualitative or quantitative description of the transition state (41, 42).

The KIE observed for an enzyme-catalyzed reaction is a function of both the intrinsic KIE in the chemical step and the rate constants for nonchemical steps such as substrate binding and release, formation of intermediates, and conformational changes (38, 43). For the GAP334- or NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis reaction as described by eq 4, the observed KIE is an isotope effect in V/K and is given by the following:

| (8) |

| (9) |

Equation 8 predicts that the observed KIEs are reduced, relative to the intrinsic KIEs in the chemical step (18k3), by forward commitment (cf), which is the ratio of the forward rate of the Ras · GTP · GAP complex (k3) to the net rate of GTP release from this complex to the solution. There has been no evidence in the literature for reversible cleavage the Pγ–Oβγ bond; therefore, a reverse commitment is not considered here. Two terms, k3/k−2 and 1+ k2/k−1, contribute to cf. The first term is an internal commitment and relies only on the kinetic properties of the Ras · GTP · GAP complex, whereas the second term depends on the concentrations of Ras · GTP and GAP. In order to maximize the observed KIE, experimental conditions were designed to minimize 1+ k2/k−1. First, a guanine nucleotide exchange factor, either Cdc25Mm285 or SOS1, was included in the reaction mixture to accelerate GTP release from Ras · GTP (k−1). Second, with the exception of very slow reactions, such as the hydrolysis catalyzed by Ras(Q61H)-NF1333, only catalytic amounts of GAP were used so that k2 is minimized. For all reactions, the observed KIEs did not change when the concentration of GAP was varied several fold in either direction. Since k2 is expected to depend on the free concentration of GAP, the independence of KIEs on GAP concentration suggests that1+ k2/k−1 is very close to unity and does not significantly contribute to cf.

Transition State Structure for Ras-Catalyzed GTP Hydrolysis Is Loose

We previously reported the KIEs in the GTP hydrolysis reaction catalyzed by Ras (23). Having improved our analytical method (30) and adopted different reaction conditions, we redetermined these KIEs and report the values in Table 1. In contrast to the previous experiments, which were carried out using catalytic amounts of Cdc25Mm285 at 37 °C, stoichiometric amounts of Cdc25Mm285 were used in the present study and the reactions were carried out at room temperature. Despite these differences in reaction conditions, the KIEs for γ18O3-, γ18O4-, β18O3-, and β18O2-labeling are in agreement with previously reported values within experimental errors.

The nature of the transition state structure for a phosphoryl transfer reaction is revealed by the KIEs in the leaving oxygen and in the geminal nonbridge oxygens (44, 45). The comparable quantities for GTP hydrolysis are the KIEs in γ18O3- and β18O3- labeling, which reflect the changes in bond orders of the three γ nonbridge oxygens and the extent of cleavage of the Pγ–Oβγ bond, respectively. While interpretation of the KIE in the nonbridge oxygens can be complicated by the extent of proton transfer to the γ phosphoryl group at the transition state (46), the magnitude of the KIE in the leaving group oxygen is generally accepted as a reliable indicator of the nature of the transition state (44, 47). It is estimated by quantum-mechanical calculations that the KIE in β18O3 for a dissociative pathway is around 1.03 (York, D., personal communication). The observed KIE of 0.9994 in γ18O3-labeling and of 1.0192 in β18O3-labeling reveal that the Ras-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis involves a loose transition state (23).

The KIE in β18O2-labeling is 1.0078, indicating that the Pβ–Oβ nonbridge bonds are weakened in the transition state. This reduction in bond order presumably arises through resonance structures that allow distribution of the charge, which results from cleavage of the Pγ–Oβ–γ bond, onto the two β nonbridge oxygens (23). The KIEs of 1.0042 in the pro-S oxygen and of 1.0028 in pro-R β oxygen suggest that charge increases slightly more on the pro-S β oxygen than the pro-R β oxygen. Crystal structures reveal that the pro-R β oxygen is coordinated to the Mg2+ cofactor and the amide proton of Ser-17, whereas the pro- S β atom accepts hydrogen bonds from three P-loop amide groups and forms an ion-pair with the P-loop Lys-16. It is quite possible that the electrostatic potential is different at two nonbridge oxygen atoms and that the asymmetry in charge increase may reflect the difference.

GAP334- and NF1333-Stimulated GTP Hydrolysis Reactions Also Proceed through Loose Transition States

The observed KIEs of 1.0012 in γ18O3-labeling and 1.0220 for β18O3-labeling in GAP334-stimulated GTP hydrolysis are similar to the respective KIEs of 0.9994 and 1.0192 in the intrinsic GTPase reaction, indicating that GAP334 does not change the structure of the transition state. In addition, the magnitude of KIE in β18O3 indicates that the forward commitment is small and that transition-state formation is still rate-limiting in theGAP334-facilitated Ras GTPase reaction.

The KIE in β18O3 for Ras-NF1333 (1.0077) is much smaller than that for Ras-GAP334 (1.0220), which suggests that there is significant forward commitment in the NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis. This assessment is consistent with biochemical properties of NF1333 reported in the literature. The rate of dissociation of NF1333 from Ras · GTP · NF1333 (k−2) was estimated to be 5.5 s−1 (7), and the rate of GTP cleavage (k3) stimulated byNF1333 was reported to be 5.4 s−1 (27) or 19.5 s−1 (7) in two separate studies. These rates predict a cf (k3/k−2) in the range between 0.93 and 3.5, which, for an intrinsic isotope effect close to 1.02, could lead to an observed KIE in the range of 1.005 to 1.01, consistent with the measured value of 1.0077. If the commitment factor is very small, as is expected for the arginine finger mutant, NF1333(R1276A), a much larger KIE (1.0202) is observed. Therefore, the intrinsic KIE in β18O3 for Ras-NF1333 is probably as large as that for Ras-GAP334, and it follows that NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis reactions proceed through a loose transition state as well.

Charge Asymmetry at the pro-S and pro-R β Oxygens Increases in GAP-Facilitated Reactions

The asymmetry in the KIEs in the pro-S and pro-Rβ oxygens noted for the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras is amplified in the GAP-facilitated reactions. The KIEs in pro-S β oxygen and pro-R β oxygen for Ras-GAP334 are 1.0044 and 1.0006, respectively, indicating that there is significant increase in the charge on the pro-S oxygen but not on the pro-R β oxygen at the transition state. KIEs for Ras-NF1333 are 1.0012 and 0.9975 in pro-S β and pro-R β oxygen, respectively, indicating that there is a decrease rather than an increase of charge on the pro-R β oxygen. The inverse nature of the KIE in pro-R β oxygen is confirmed by the observation that the KIE in β18O2-labeling (1.0000) is less than that in pro-S β oxygen alone (1.0012).Note also that the intrinsic KIE in the pro-R β oxygen for the Ras-NF1333-catalyzed reaction is more inverse than the observed KIE of 0.9975 because of the significant commitment in the reaction. In summary, GAP334- and NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis reactions share the loose nature of the transition states but not the pattern of charge increase on the pro-S and pro-R β oxygens.

Charge Increases Prominently on the β–γ Bridge Oxygen in GAP-Facilitated Reactions

Since the charge due to the cleavage of Pγ–Oβγ bond at the transition state is shared between the β–γ bridge oxygen and the two β nonbridge oxygens, it is of mechanistic interest to compare the pattern of charge increase on the three oxygens in different reactions. Computational studies on the hydrolysis of methyl triphosphate reveals that the KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen likely has significant contribution from the reaction coordinate (York, D., personal communication) for a concerted mechanism. Therefore, the KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen overestimates the charge increase on the β–γ bridge oxygen relative to the charge increase on the two β nonbridge oxygens at the transition state of a reaction. Here, we compare the KIEs in reactions catalyzed by Ras and Ras mutants in the presence of wild type and mutant GAPs and infer qualitative differences in charge distribution between these reactions. Contribution to the KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen from the reaction coordinate presumably remains the same in different reactions, and the differences in the KIEs are due to changes in bond orders only, which is directly related to charge increase. Indeed, in all cases, an inverse relationship is observed between the magnitude of the KIE in the bridge oxygen and that in β18O2, which is consistent with conservation of charge and validates the correlation between change in charge and KIE.

The KIE in the β–γ bridge oxygen for the GAP334-facilitated GTPase reaction is significantly larger (1.0161) than that for the intrinsic GTPase reaction (1.0113) even though the KIEs in β18O3-labeling for the two reactions are similar (1.0220 vs 1.0192). Concomitantly, the KIE in β18O2-labeling in GAP334-facilitated GTP hydrolysis is smaller (1.0057) than that for the intrinsic reaction (1.0078). These data suggest that in GAP334-facilitated GTP hydrolysis there is more charge on the β–γ bridge oxygen and less on the two β nonbridge oxygens than in the reaction catalyzed by the intrinsic activity of Ras. Because of the substantial, but imprecisely known, commitment in the NF1333-facilitated GTPase reaction, the KIEs for Ras-NF1333 cannot be compared directly with those in the reaction catalyzed by Ras alone. However, a concentration of charge on the β–γ bridge oxygen similar to that seen in the GAP334-facilitated GTPase reaction can be deduced by comparing the KIEs in the β–γ bridge and β nonbridge oxygens. A KIE of unity (1.0000) in β18O2 for Ras-NF1333 indicates that there is no overall charge increase on the two β nonbridge oxygens at the transition state. The KIE in the β–γ bridge (1.0068), however, is very close to the KIE in β18O3-labeling (1.0077), indicating that almost all charge increase occurs on the β–γ bridge oxygen. Thus, in both GAP334-and NF1333-assisted reactions, charge increases on the β–γ bridge oxygen at the expense of β nonbridge oxygens as compared with the reaction catalyzed by Ras alone. A computational study also showed that GAP334 increases electrostatic potential at the bridge oxygen (28). The increase was attributed not only to the presence of the positive charge on the arginine finger but also to the conformation of Ras in the crystal structure of Ras · GDP · AlF3:GAP334, which was found to exert higher electrostatic potential at the β–γ bridge oxygen than the conformation of Ras in the crystal structure of Ras · GPPNP (28). The KIE data, together with the computational study, indicate that even though GAPs do not change the nature of the transition state, they can change the charge distribution of the transition state.

The GAP Arginine Finger Stabilizes Charge at the β–γ Bridge Oxygen at the Transition State

In the crystal structure of Ras · GDP · AlF3:GAP334, Arg-789 of GAP334 interacts with both the would-be β–γ bridge oxygen and one of the γ nonbridge oxygens. It is generally accepted that the arginine finger of GAP participates in catalysis by stabilizing the transition state. However, without the knowledge of the structure of the transition state, it is not clear whether Arg-789 stabilizes the negative charge on the β–γ bridge oxygen of a loose transition state (13) or the charge on one of the γ nonbridge oxygens of a tight (associative-like) transition state.

In agreement with an earlier report, we found that GAP 334(R789A) stimulates the GTPase of Ras only marginally (27). Consequently, it was not possible to measure KIEs for Ras-GAP334(R789A) because the GTP hydrolysis due to intrinsic GTPase was significant relative to the overall level of hydrolysis even in the presence of a stoichiometric amount of GAP 334(R789A). NF1333(R1276A) is also a weak GAP but retains sufficient activity for measurement of KIEs (27). The KIE of 1.0202 in β18O3 for Ras-NF1333(R1276A) is much larger than that of 1.0077 for wild type Ras-NF1333, which is consistent with a much reduced cf as a result of the reduced turnover rate (k3). In contrast, the mutation does not cause any change in the KIE in γ18O3, which is 0.9994 for Ras-NF1333(R1276A) and 0.9992 for Ras-NF1333. This would be expected if there is no change in mechanism because the change in commitment alone is not expected to affect a KIE that is close to unity. Therefore, we can conclude that the mutation of the arginine finger does not change the nature of the transition state of NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis. This is in keeping with our finding that wild type GAP334 orNF1333, with the arginine fingers, does not change the nature of the transition state of GTP hydrolysis catalyzed by Ras alone. A similar finding was made on studies of Yersinia protein tyrosine phosphatase, where mutation of a conserved Arg residue that interacts with the phosphoryl group does not alter the transition state (47). Together, these results would seem to argue against the notion that positive charges interacting with the phosphoryl group can change the nature of the transition state of the hydrolysis reaction of phosphate monoesters.

The mutation of Arg-1276 to Ala leads to increases in the KIEs in β nonbridge oxygens. Whereas the KIE in β18O2 (1.0000) indicates that there is no overall change of charge at the transition state on the two β nonbridge oxygens forRas-NF1333, the KIE in β18O2 (1.0069) is significant for Ras-NF1333(R1276A). Comparison of the KIEs in the β–γ bridge oxygen can be made only after scaled by the KIEs in β18O3 to remove the differences in commitment factors in these two reactions. The comparison of the KIEs in β18O2 for Ras-NF1333(0.68%/0.77%) and for NF1333(R1276A) (1.34%/2.02%) suggests the mutation results in smaller charge increase at the β–γ bridge oxygen atom at the transition state. These KIEs support the conclusion that Arg-1276 is a determinant of the electrostatic potential at the β–γ bridge oxygen and the mutation of Arg-1276 to Ala lowers the electrostatic potential at the β–γ bridge oxygen. The effect of the mutation on the charge distribution on the leaving group oxygens, together with early observation that there is no charge increase on the γ-nonbridge oxygens, strongly supports the proposal that the arginine finger of GAP facilitates GTPase of Ras by stabilizing the negative charge on the β–γ bridge oxygen of a loose transition state.

Lys-16 of Ras Is Involved in Substrate Binding but Not Transition State Stabilization

Lys-16 is highly conserved in P-loop nucleotide triphosphatases (48). In crystal structures of G proteins bound to GTP and GTP analogues, the conserved lysine residue is invariably found to engage in ionic interactions with both the pro-S β nonbridge oxygen and one of the γ nonbridge oxygens (24, 49, 50). It was postulated that Lys-16 is involved in stabilizing the negative charge on the pro-S oxygen at a loose transition state (13) or the negative charge on the γ nonbridge oxygen at a tight transition state (51–53).

Ras(K16A) has not been heretofore biochemically characterized, probably because it is difficult to express in E. coli as active protein. We obtained active Ras(K16A) by coexpression with CDC25Mm285. The complex prepared in this way exhibited GTPase activity in the presence of either GAP334 or NF1333. As expected, the K16A mutation impairs the GAP-facilitated GTPase activity such that roughly 200-fold higher GAP334 or 35-fold higher NF1333 concentration was needed to achieve a steady state rate comparable to that for wild type Ras with GAP334 or NF1333, respectively. Rather surprisingly, the mutation of Lys-16 to Ala does not alter the KIEs in β18O3, β18O2, pro-S β18O, or pro-R β18O in either GAP334- or NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis. Inspection of eq 5 reveals that a mutation of Ras can impair the steady state rate in three ways: by reducing the turnover rate (k3); by increasing Km of Ras · GTP for GAP; or by reducing the affinity of Ras for GTP and thereby lowering the concentration of Ras · GTP. The first two possibilities are unlikely. A decrease in k3 or an increase in k−2, which is the only realistic way to increase Km, is expected to lower the commitment (k3/k−2) and lead to a significant increase in the observed KIEs. The paradoxical lack of any effect of the Lys-16 mutation on the KIEs despite its impairment of the steady state rate can be explained by the third possibility, that is, the mutation of Lys-16 reduces the affinity of Ras for GTP and therefore effectively reduces the steady state concentration of Ras · GTP. The mutation need not affect the rate of cleavage (k3) or the dissociation of GAP from Ras · GTP (k−2), thereby leaving the commitment and KIEs unchanged. This proposal is consistent with the observation that the K16A mutation does not change the KIEs in the pro-S β, pro-R β, and the β–γ bridge oxygens, which suggests that the interaction of Lys-16 with the pro-R β oxygen atom is not strong enough to affect charge distribution on the three oxygen atoms at the transition state.

The proposed effect of the K16A mutation on the affinity of Ras for GTP offers a ready explanation for the observation that NF1333 is more efficient than GAP334 in stimulating the GTPase activity of Ras(K16A), the reverse of the case for wild type Ras (Table 1). As a consequence of weak binding of Ras(K16A) to GTP, the concentration of Ras(K16A) · GTP is likely much lower than Km for Ras(K16A)-GAP334 or Ras(K16A)-NF1333. Consequently, the reaction rate depends on k3/Km as described by eq 7, instead of k3, as is the case for wild type Ras and GAP. Although k3 is slightly higher for GAP334, NF1333 is the more effective enzyme toward Ras(K16A) by virtue of its lower Km (0.1 µM vs 5 µM) (7, 27).

Although the mutation of Lys-16 to Ala does not affect the KIEs in β oxygens, it does lower the KIEs in γ18O3 from 1.0012 for Ras-GAP334 to 0.9989 for Ras(K16A)-GAP334. A concomitant decrease from 1.0172 to 1.0140 is also observed in the KIEs for [γ18O4]GTP, which shares the 18O-labels at the three γ nonbridge oxygen positions with [γ18O3]GTP. The decreases of 0.0023 and 0.0032 in these KIEs are statistically significant in light of the observation that differences in KIEs in β18O3, β18O2, pro-S β18O, and pro-R β18O for Ras-GAP334 and Ras(K16A)-GAP334 are all less than 0.0006. In an internal competition experiment, the isotope effects on V/K are measured. As discussed above, the K16A mutation does not affect V(k3) of the reaction. Therefore, the reductions in the KIEs in γ18O3 and γ18O4 likely reflect a change in the isotope effect in binding of Ras to the γ nonbridge oxygens. If so, the KIE data suggest that Lys-16 contributes as much as 0.002 or 0.003 to the isotope effect in binding.

Mutation of Gln-61 Disrupts the Stabilization of the Leaving Group Oxygens

Gln-61 of Ras is a highly conserved residue in the G protein superfamily (54). Ras proteins mutated at Gln-61 are frequently found in cancers. Such mutations are oncogenic because they impair the intrinsic and GAP-facilitated GTPase activity of Ras, which results in an abnormally prolonged state of effector activation (8). The perceived roles of Gln-61 in catalysis have been evolving ever since the crystal structure of Ras was solved. An earlier proposal that Gln-61 is involved in the activation of the water molecule was disputed on the basis that Gln-61 is a weak base (24, 51, 55, 56). Mutational and computational studies argue effectively against the proposal that Gln-61 is involved in transition state stabilization (28, 56). The crystal structure of Ras · GDP · AlF3 · GAP334 complex suggests that Gln-61 aligns the attacking water molecule and the γ-phosphoryl group with respect to the protein (26). In the metaphosphate-as-intermediate model, Gln-61 was proposed to mediate the proton transfer from the water to the metaphosphate intermediate (16, 57).

To probe its role in catalysis, we mutated Gln-61 to His, an amino acid that still confers weak activity upon Ras in the presence ofNF1333 (6). The virtually identical KIEs of 0.9992 and 0.9991 in γ18O3 for Ras-NF1333 and Ras(Q61H)-NF1333, respectively, argues against the proposed role ofGln-61 as a mediator of proton transfer in the metaphosphate-as-intermediate model. The KIE of 1.0179 in β18O3 is much larger than that for wild type Ras and NF1333 (1.0077), which is consistent with a much smaller commitment as a result of the smaller turn over rate (k3). Surprisingly, a drastic effect of the mutation was observed on the KIEs in the leaving group oxygens. KIEs in the β–γ bridge oxygen (1.0087) and in β18O2 (1.0096), when compared with those for the corresponding reactions with wild type Ras (1.0068 and 1.0000, respectively), indicate significantly higher charge increases in the two β nonbridge oxygens and concomitantly less charge increases on the β–γ bridge oxygen. The KIE of 1.0046 in pro-S β oxygen and 1.0062 in pro-R β oxygen suggest that there is greater charge increase on the pro-Rβ oxygen than on the pro-S β oxygen, which is a reversal of the pattern observed for Ras-NF1333. These results suggest that the Q61H mutation leads to substantial changes in the electrostatic potential at the three leaving oxygens and, in particular, reduces the electrostatic potential at the β–γ bridge oxygen. This is surprising in light of the observation that Gln-61 does not interact with the leaving group oxygens directly in the crystal structure of Ras · GDP · AlF3:GAP334 (29). Thus, the KIE data suggest a previously unsuspected role of Gln-61 in organizing features of the active site that are involved in stabilizing the leaving group oxygens. The side chain NH2 group of Gln-61 and the guanidinium moiety of GAP Arg-789 form hydrogen bonds with the same γ nonbridge oxygen. In addition, the NH2 group of the Gln-61 side chain also forms a hydrogen bond with the main chain carbonyl group of Arg-789. It is conceivable that the removal of these interactions by the mutation of Gln-61 disrupts the correct positioning of the arginine finger in the active site of Ras and renders this residue unavailable for stabilizing the transition state.

Roles of Residues of Ras and GAP in Catalysis

A dominant theme revealed by the KIEs is that the transition state for Ras-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis is loose. This is the case for reactions catalyzed by the intrinsic GTPase activity of Ras as well as GAP334- or NF1333-facilitated Ras GTPase activity. Likewise, hydrolysis reactions catalyzed by Ras or GAP mutants proceed through similar transition states. The KIEs in γ18O3 are close to unity for all of the reactions. The intrinsic KIEs in β18O3 for GAP-facilitated GTP hydrolysis are around 1.02. These KIEs are in the range typically observed for the hydrolysis of phosphomonoesters, of which GTP is one example. In accordance with the existing body of evidence, the KIEs are consistent with loose transition states, in which charge is distributed on the β–γ bridge oxygen and (by resonance effects) the β-nonbridge oxygen atoms. This charge distribution imposes specific mechanistic requirements on an enzyme that accelerates the reaction by transition state stabilization. Specifically, we expect that interactions that stabilize charge at leaving group oxygens afford preferential stabilization of a loose transition state and are conducive to catalysis. Interactions with the γ phosphoryl group, while likely important for aligning the γ phosphoryl group, attacking water, and active site residues, do not provide electrostatic stabilization of the transition state. A second theme that arises from this work is that the distribution of charge among the three leaving group oxygens can differ significantly among reactions catalyzed by Ras, Ras mutants, and Ras–GAP complexes, presumably reflecting differences in electrostatic potential at those positions. Below, we discuss the catalytic roles of several active site residues in Ras, including the Mg2+ cofactor, and the catalytic arginine finger in Ras GAPs in light of the pattern of charge distribution on the pro-R β, pro-S β, and the β–γ bridge oxygens.

Mg2+ Cofactor

In general, Mg2+ provides electrostatic stabilization of substrate or the transition state in enzymatic reactions as a cofactor. In the structures of G proteins in complex with GTP, Mg2+ interacts with the pro-R β oxygen and one of the γ nonbridge oxygens (53, 54). In the two GAP-facilitated reactions, KIEs in γ18O3 are close to unity, whereas KIEs in the pro-R β oxygen are either unity or inverse. Thus, KIE data reveals no charge increase on the γ nonbridge oxygens or the pro- R β oxygen, suggesting that Mg2+ does not preferentially stabilize the transition state in GAP-facilitated GTP hydrolysis. Its role in catalysis is likely limited to orientating GTP and neutralizing its negative charge in the ground state.

Ras Lys-16

The amine group of the conserved P loop lysine residue interacts with both the pro-S β nonbridge oxygen and one of the γ nonbridge oxygens (24). The mutation of Lys-16 to Ala changes neither forward commitment nor the pattern of charge distribution on the three leaving oxygens in either GAP334- or NF1333-facilitated GTP hydrolysis, strongly suggesting that Lys-16 is not involved in transition state stabilization. The effect of the mutation on KIEs in γ18O3- or γ18O4-labeling reveals its role in GTP binding through its interaction with one of the γ nonbridge oxygens.

P-Loop Amides

The amide proton of Ras Gly-13 forms a short hydrogen bond with the β–γ bridge oxygen, whereas the amide protons of residues 14, 15, and 16 interact with the pro-S β oxygen (24). In GTP hydrolysis facilitated by both GAP334 and NF1333, the KIEs in the β–γ bridge oxygen and the pro-S β nonbridge oxygen are normal and significant (the observed KIEs for Ras-NF1333 need to be adjusted for a commitment factor), revealing charge increase on these two oxygen atoms at the transition state. Therefore, the amide protons of residues 13, 14, 15, and 16 are expected to afford preferential stabilization of the β–γ bridge oxygen and the pro-S β nonbridge oxygen at the transition state. The catalytic role of the Gly-13 amide proton was first recognized by Maegley et al. (13).

Ras Gln-61

Essential to the intrinsic or GAP-facilitated GTPase activity of Ras, Gln-61 has been proposed to align the attacking water with respect to the γ phosphoryl group or to mediate proton transfer from the attacking water to the phosphoryl group. The effect of its mutation on the KIEs in the leaving oxygens suggests that Gln-61 is important for maintaining features of the active site that stabilize the charge on the leaving group oxygen, although the mechanism by which it might provide such stabilization is not obvious. It is also possible that histidine substitution in particular is responsible for perturbations in KIE. Perhaps more important, the mutation does not change the KIE in γ18O3, which argues against its role as a mediator of proton transfer.

GAP Arginine Finger

It is generally accepted that the arginine finger of GAP accelerates GTP hydrolysis by providing an additional level of transition state stabilization (26). The KIEs for Ras-NF1333 and Ras-GAP334 reveal the loose nature of the transition state and the significant charge buildup on the β–γ bridge oxygen at the transition state. Moreover, the KIEs for Ras-NF1333(R1276A) reveal that the mutation of the arginine finger influences the transition state charge increase on the β–γ bridge oxygen but not on the γ nonbridge oxygen. Overall, these data strongly suggest that the arginine finger facilitates the GTPase activity of Ras by stabilizing the charge on the β–γ bridge oxygen at the transition state.

CONCLUSIONS

There is considerable evidence in the literature to support the notion that GAP proteins function by reorganizing the Switch II of Ras and by electrostatically stabilizing the transition state. The allosteric effect of GAP is critical for the correct positioning of the nucleophilic water and is potentially important for the proton transfer from the nucleophilic water to the phosphate product or bulk medium. The results of the experiments presented here define the loose nature of the transition state structures and emphasize the effect of transition state stabilization afforded by GAP. The participation of GAP does not change the nature of the transition state, which remains loose in a GAP-facilitated reaction. However, GAP changes the charge distribution among the three leaving group oxygens at the transition state, suggesting that GAP increases the electrostatic potential at the β–γ bridge oxygen and the pro-S β oxygen positions. In particular, the KIE data provide strong support to the hypothesis that the arginine finger of Ras GAPs stabilizes the charge at the β–γ bridge oxygen at the transition state.

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We thank Dr. Alfred Wittinghofer at Max Planck Institute for providing plasmids of Cdc25Mm285, GAP334, and NF1333, Drs. Robert Gregory and Kurt Furgerson at the Stable Isotope Laboratory, Southern Methodist University for granting access to their MAT252 and providing excellent technical support, Dr. Frantz Eckstein at Max Planck Institute for personal communication on the synthesis of stereospecific S-GTP, Dr. Daniel Herschlag for critically reading the manuscript, and Dr. Darrin York at University of Minnesota for personal communication on the computational study on the hydrolysis of methyltriphosphate. Special thanks go to Reginald Du for proof-reading. The characterization of 18O-, 13C-labeled nucleotides by electro-spray mass spectrometry was carried out by the Protein Chemistry Technology Center at The University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center.

Footnotes

This project was supported by National Institutes of Health grant GM0714420.

Abbreviations: GTP, guanosine 5′ triphosphate; GDP, guanosine 5′ diphosphate; GMP, guanosine 5′ monophosphate; KIE, kinetic isotope effect; GAP, GTPase activation protein; NF1, neurofibromin; IRMS, isotope ratio mass spectrometry.

SUPPORTING INFORMATION AVAILABLE

The schemes for the synthesis of the double-labeled nucleotides. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

References

- 1.Bourne HR, Sanders DA, McCormick F. The GTPase superfamily: a conserved switch for diverse cell functions. Nature (London) 1990;348:125–132. doi: 10.1038/348125a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cox AD, Der CJ. The dark side of Ras: regulation of apoptosis. Oncogene. 2003;22:8999–9006. doi: 10.1038/sj.onc.1207111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Boguski MS, McCormick F. Proteins regulating Ras and its relatives. Nature (London) 1993;366:643–654. doi: 10.1038/366643a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Trahey M, McCormick F. A cytoplasmic protein stimulates normal N-ras p21 GTPase, but does not affect oncogenic mutants. Science. 1987;238:542–545. doi: 10.1126/science.2821624. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Xu GF, Lin B, Tanaka K, Dunn D, Wood D, Gesteland R, White R, Weiss R, Tamanoi F. The catalytic domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 gene product stimulates ras GTPase and complements ira mutants of S. cerevisiae. Cell. 1990;63:835–841. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(90)90149-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gideon P, John J, Frech M, Lautwein A, Clark R, Scheffler JE, Wittinghofer A. Mutational and kinetic analyses of the GTPase-activating protein (GAP)-p21 interaction: the C-terminal domain of GAP is not sufficient for full activity. Mol. Cell. Biol. 1992;12:2050–2056. doi: 10.1128/mcb.12.5.2050. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Phillips RA, Hunter JL, Eccleston JF, Webb MR. The mechanism of Ras GTPase activation by neurofibromin. Biochemistry. 2003;42:3956–3965. doi: 10.1021/bi027316z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bos JL. ras oncogenes in human cancer: a review. Cancer Res. 1989;49:4682–4689. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Serra E, Puig S, Otero D, Gaona A, Kruyer H, Ars E, Estivill X, Lazaro C. Confirmation of a double-hit model for the NF1 gene in benign neurofibromas. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 1997;61:512–519. doi: 10.1086/515504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benkovic SJ, Schray KJ. Transition States of Biochemical Processes. In: Grandour RD, Schowen R, editors. Transition States of Biochemical Processes. New York: Plenum Press; 1978. pp. 493–527. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Thatcher G, Kluger R. In: Advances in Physical Organic Chemistry. Bethell D, editor. New York: Academic Press; 1989. pp. 99–265. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Admiraal SJ, Herschlag D. Mapping the transition state for ATP hydrolysis: implications for enzymatic catalysis. Chem. Biol. 1995;2:729–739. doi: 10.1016/1074-5521(95)90101-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Maegley KA, Admiraal SJ, Herschlag D. Ras-catalyzed hydrolysis of GTP: a new perspective from model studies. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1996;93:8160–8166. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.16.8160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hengge AC. Isotope effects in the study of phosphoryl and sulfuryl transfer reactions. Acc. Chem. Res. 2002;35:105–112. doi: 10.1021/ar000143q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Grigorenko BL, Nemukhin AV, Cachau RE, Topol IA, Burt SK. Computational study of a transition state analog of phosphoryl transfer in the Ras-RasGAP complex: AlF(x) versus MgF3. J. Mol. Model. 2005;11:503–508. doi: 10.1007/s00894-005-0259-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Grigorenko BL, Nemukhin AV, Shadrina MS, Topol IA, Burt SK. Mechanisms of guanosine triphosphate hydrolysis by Ras and Ras-GAP proteins as rationalized by ab initio QM/MM simulations. Proteins. 2007;66:456–466. doi: 10.1002/prot.21228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Schweins T, Geyer M, Kalbitzer HR, Wittinghofer A, Warshel A. Linear free energy relationships in the intrinsic and GTPase activating protein-stimulated guanosine 5′-triphosphate hydrolysis of p21ras. Biochemistry. 1996;35:14225–14231. doi: 10.1021/bi961118o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Schweins T, Geyer M, Scheffzek K, Warshel A, Kalbitzer HR, Wittinghofer A. Substrate-assisted catalysis as a mechanism for GTP hydrolysis of p21ras and other GTP-binding proteins. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1995;2:36–44. doi: 10.1038/nsb0195-36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Klahn M, Rosta E, Warshel A. On the mechanism of hydrolysis of phosphate monoesters dianions in solutions and proteins. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2006;128:15310–15323. doi: 10.1021/ja065470t. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du X, Frei H, Kim SH. The mechanism of GTP hydrolysis by Ras probed by Fourier transform infrared spectroscopy. J. Biol. Chem. 2000;275:8492–8500. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.12.8492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Allin C, Gerwert K. Ras catalyzes GTP hydrolysis by shifting negative charges from gamma- to beta-phosphate as revealed by time-resolved FTIR difference spectroscopy. Biochemistry. 2001;40:3037–3046. doi: 10.1021/bi0017024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cheng H, Sukal S, Deng H, Leyh TS, Callender R. Vibrational structure of GDP and GTP bound to RAS: an isotope-edited FTIR study. Biochemistry. 2001;40:4035–4043. doi: 10.1021/bi0021131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Du X, Black GE, Lecchi P, Abramson FP, Sprang SR. Kinetic isotope effects in Ras-catalyzed GTP hydrolysis: evidence for a loose transition state. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 2004;101:8858–8863. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0401675101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pai EF, Krengel U, Petsko GA, Goody RS, Kabsch W, Wittinghofer A. Refined crystal structure of the triphosphate conformation of H-ras p21 at 1.35 A resolution: implications for the mechanism of GTP hydrolysis. EMBO J. 1990;9:2351–2359. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1990.tb07409.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Milburn MV, Tong L, deVos AM, Brunger A, Yamaizumi Z, Nishimura S, Kim SH. Molecular switch for signal transduction: structural differences between active and inactive forms of protooncogenic ras proteins. Science. 1990;247:939–945. doi: 10.1126/science.2406906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Scheffzek K, Ahmadian MR, Kabsch W, Wiesmuller L, Lautwein A, Schmitz F, Wittinghofer A. The Ras-RasGAP complex: structural basis for GTPase activation and its loss in oncogenic Ras mutants. Science. 1997;277:333–338. doi: 10.1126/science.277.5324.333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Ahmadian MR, Stege P, Scheffzek K, Wittinghofer A. Confirmation of the arginine-finger hypothesis for the GAP-stimulated GTP-hydrolysis reaction of Ras. Nat. Struct. Biol. 1997;4:686–689. doi: 10.1038/nsb0997-686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Glennon TM, Villa J, Warshel A. How does GAP catalyze the GTPase reaction of Ras? A computer simulation study. Biochemistry. 2000;39:9641–9651. doi: 10.1021/bi000640e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Scheffzek K, Ahmadian MR, Wiesmuller L, Kabsch W, Stege P, Schmitz F, Wittinghofer A. Structural analysis of the GAP-related domain from neurofibromin and its implications. EMBO J. 1998;17:4313–4327. doi: 10.1093/emboj/17.15.4313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Du X, Ferguson K, Gregory R, Sprang SR. A method to determine 18O kinetic isotope effects in the hydrolysis of nucleotide triphosphates. Anal. Biochem. 2008;372:213–221. doi: 10.1016/j.ab.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Connolly BA, Romaniuk PJ, Eckstein F. Synthesis and characterization of diastereomers of guanosine 5′-O-(1-thiotriphosphate) and guanosine 5′-O-(2-thiotriphosphate) Biochemistry. 1982;21:1983–1989. doi: 10.1021/bi00538a002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Connolly BA, Eckstein F, Fuldner HH. Streospecific substitution of oxygen-18 for sulfur in nucleoside phosphorothioates. J. Biol. Chem. 1982;257:3382–3384. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Miura K, Inoue Y, Nakamori H, Iwai S, Ohtsuka E, Ikehara M, Noguchi S, Nishimura S. Synthesis and expression of a synthetic gene for the activated human c-Ha-ras protein. Jpn J. Cancer Res. 1986;77:45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Boriack-Sjodin PA, Margarit SM, Bar-Sagi D, Kuriyan J. The structural basis of the activation of Ras by Sos. Nature (London) 1998;394:337–343. doi: 10.1038/28548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Jacquet E, Baouz S, Parmeggiani A. Characterization of mammalian C-CDC25Mm exchange factor and kinetic properties of the exchange reaction intermediate p21.C-CDC25Mm. Biochemistry. 1995;34:12347–12354. doi: 10.1021/bi00038a031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Wiesmuller L, Wittinghofer A. Expression of the GTPase activating domain of the neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1) gene in Escherichia coli and role of the conserved lysine residue. J. Biol. Chem. 1992;267:10207–10210. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lenzen C, Cool RH, Wittinghofer A. Analysis of intrinsic and CDC25-stimulated guanine nucleotide exchange of p21ras-nucleotide complexes by fluorescence measurements. Methods Enzymol. 1995;255:95–109. doi: 10.1016/s0076-6879(95)55012-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Cleland WW. Use of isotope effects to elucidate enzyme mechanisms. CRC Crit. Rev. Biochem. 1982;13:385–428. doi: 10.3109/10409238209108715. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hermes JD, Morrical SW, O’Leary MH, Cleland WW. Variation of Transition-state structure as a function of the nucleotide in reaction catalyzed by dehydrogenase. 2. Formate dehydrogenase. Biochemistry. 1984;23:5479–5488. doi: 10.1021/bi00318a016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Melander L, Saunders WH. Reaction Rates of Isotopic Molecules. New York: John Wiley & Sons; 1980. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cleland WW. Isotope effects: determination of enzyme transition state structure. Methods Enzymol. 1995;249:341–373. doi: 10.1016/0076-6879(95)49041-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Schramm VL, Horenstein BA, Kline PC. Transition state analysis and inhibitor design for enzymatic reactions. J. Biol. Chem. 1994;269:18259–18262. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Northrop DB. The expression of isotope effects on enzyme-catalyzed reactions. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1981;50:103–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.000535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cleland WW, Hengge AC. Mechanisms of phosphoryl and acyl transfer. FASEB J. 1995;9:1585–1594. doi: 10.1096/fasebj.9.15.8529838. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Cleland WW, Hengge AC. Enzymatic mechanisms of phosphate and sulfate transfer. Chem. Rev. 2006;106:3252–3278. doi: 10.1021/cr050287o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Aqvist J, Kolmodin K, Florian J, Warshel A. Mechanistic alternatives in phosphate monoester hydrolysis: what conclusions can be drawn from available experimental data? Chem. Biol. 1999;6:R71–R80. doi: 10.1016/S1074-5521(99)89003-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hoff RH, Wu L, Zhou B, Zhang ZY, Hengge AC. Does positive charge at the active sites of phosphatases cause a change in mechanism? The effect of the conserved arginine on the transition state for phosphoryl transfer in the protein-tyrosine phosphatase from Yersinia. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1999;121:9514–9521. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Leipe DD, Koonin EV, Aravind L. Evolution and classification of P-loop kinases and related proteins. J. Mol. Biol. 2003;333:781–815. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2003.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Coleman DE, Berghuis AM, Lee E, Linder ME, Gilman AG, Sprang SR. Structures of active conformations of Gi alpha 1 and the mechanism of GTP hydrolysis. Science. 1994;265:1405–1412. doi: 10.1126/science.8073283. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Noel JP, Hamm HE, Sigler PB. The 2.2 A crystal structure of transducin-alpha complexed with GTP gamma S. Nature (London) 1993;366:654–663. doi: 10.1038/366654a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Prive GG, Milburn MV, Tong L, de Vos AM, Yamaizumi Z, Nishimura S, Kim SH. X-ray crystal structures of transforming p21 ras mutants suggest a transition-state stabilization mechanism for GTP hydrolysis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992;89:3649–3653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.89.8.3649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Schlichting I, Almo SC, Rapp G, Wilson K, Petratos K, Lentfer A, Wittinghofer A, Kabsch W, Pai EF, Petsko GA, et al. Time-resolved X-ray crystallographic study of the conformational change in Ha-Ras p21 protein on GTP hydrolysis. Nature (London) 1990;345:309–315. doi: 10.1038/345309a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Wittinghofer A, Pai EF. The structure of Ras protein: a model for a universal molecular switch. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1991;16:382–387. doi: 10.1016/0968-0004(91)90156-p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Sprang SR. G protein mechanisms: insights from structural analysis. Annu. Rev. Biochem. 1997;66:639–678. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.66.1.639. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Foley CK, Pedersen LG, Charifson PS, Darden TA, Wittinghofer A, Pai EF, Anderson MW. Simulation of the solution structure of the H-ras p21-GTP complex. Biochemistry. 1992;31:4951–4959. doi: 10.1021/bi00136a005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Chung HH, Benson DR, Schultz PG. Probing the structure and mechanism of Ras protein with an expanded genetic code. Science. 1993;259:806–809. doi: 10.1126/science.8430333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grigorenko BL, Nemukhin AV, Topol IA, Cachau RE, Burt SK. QM/MM modeling the Ras-GAP catalyzed hydrolysis of guanosine triphosphate. Proteins. 2005;60:495–503. doi: 10.1002/prot.20472. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]