Highlights

► We present four cases of benign granular cell tumours of the vulva managed between 1998 and 2001. ► We discuss the clinical and histopathological features of this condition. ► Treatment of this condition is primarily surgical.

Keywords: Granular cell tumor, Vulva, Case report

Introduction

Granular cell tumors (GCTs) are rare neoplasms of neural sheath origin, the majority of which occur in the skin, submucosal or subcutaneous tissue of the head and neck, especially in the tongue and oral cavity. Approximately 10% involves the vulva [1], although they have also been reported in the ovary, uterus, cervix, vagina, mons pubis and episiotomy scar. GCTs are more common in women and those of negroid descent [1]. They occur in both children [2] and adults, with a higher incidence in the fifth decade of life [1]. They generally present as small, slow-growing, solitary and painless subcutaneous nodules. Most are benign; however, there have been reports of GCTs which are aggressive with multicentric or metastatic disease and can be fatal.

We present four cases of benign granular cell tumors of the vulva managed in our hospital between May 1998 and April 2011.

Case reports

Case 1

A 59 year-old Chinese female complained of a slow-growing lump on the left labial majus for nine years. She underwent an excision biopsy of the mass under general anesthesia. Histological examination showed a circumscribed tumor, composed of large polygonal cells with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and uniform-looking round to oval nuclei, forming sheets and nests irregularly infiltrating between collagen bundles, consistent with granular cell tumor. One resection tip was involved. The patient is currently on follow-up and there have been no signs of recurrence.

Case 2

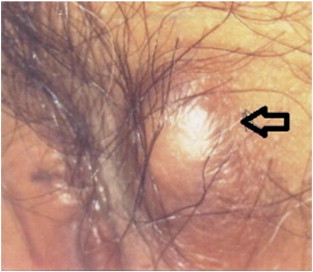

A 23 year-old Malay female complained of a right labial cyst for one year (see Fig. 1). It was stable in size with no other symptoms. She underwent an excision biopsy of the mass under local anesthesia. Histological examination showed a well-circumscribed nodule composed of sheets and occasional closely-packed clusters of polygonal cells with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and small central nuclei consistent with a granular cell tumor. The tumor involved the resection margins. She subsequently had a 3 mm right vulval skin tag excised 5 months after her initial surgery, and histology revealed a fibroepithelial polyp. She defaulted after 16 months of follow-up.

Fig. 1.

Solitary subcutaneous lump of left labium majus in case 1 (arrow).

Case 3

A 50 year-old Chinese female with a history of uterine fibroid and incidental finding of an asymptomatic mass on the right labia majus underwent laparoscopic and hysteroscopic resection of myoma and excision biopsy of vulva lump. Histological examination showed clusters of cells with small central nuclei and abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm. The cells were positive for S-100 immunostain and showed weak focal positivity with PAS stain. These features were consistent with a granular cell tumor, and the lesional cells focally involved the specimen margins. The patient has been on yearly follow-up for 8 years and 1 month and has not shown any signs of recurrence.

Case 4

A 17 year-old Malay female complained of a left vulval lump for 1 year, which was increasing in size. She underwent an excision biopsy of a two-centimeter mass. Histology showed a nodule composed of sheets and clusters of cells traversed by delicate strands of collagenised tissue. Cells were large with abundant granular eosinophilic cytoplasm and small-to-medium sized round-to-oval nuclei. The lesion was generally circumscribed although in some areas small clusters of cells were seen extending into surrounding tissue. There was involvement of surrounding margin. Immunohistochemical stains for NSE and S-100 proteins were positive and cytokeratin was negative. She was lost to follow-up after 15 months.

Discussion

GCT was described by Abrikossoff as granular cell myoblastoma in 1926 [3]. However, immunohistochemical and ultrastructural evidence since then supports the current opinion that the tumor is neural in origin of Schwann cell derivation.

The median age in our case reports is 36.5 years old with an age range of 17–59 years. The mean age range in the literature is 30–50 years [6,7].

Some authors have suggested a familial link [8]. In one case series, three out of five cases had a history of soft tissue tumors in family members. However, most cases are sporadic and possibility of familial link needs to be investigated further.

GCTs are generally small, firm, solitary nodules that are whitish in color, lack encapsulation and are located in the subcutaneous layer. The most common location of GCT in the female genital tract is on the labium majus [4]. They are typically slow-growing and usually asymptomatic, and are sometimes confused with sebaceous cyst. However there have been reports of GCTs of the vulva, which are aggressive with multicentric or metastatic disease and can have fatal outcomes [5]. The incidence of multicentric lesions ranges from 3% to 20% [4] and this raises the suspicion of malignancy.

Although most vulvar granular cell tumors are benign, about 1 to 2% of the cases are malignant and may be associated with regional or distant metastases [9,10]. The malignant form of granular cell tumors is highly aggressive, responds poorly to radiation or chemotherapy and may sometimes have fatal outcomes where lesions are present in organs such as the lung or liver [5]. Clinically, features associated with poor prognosis include rapid tumor growth, tumor size > 4 cm, invasion into adjacent tissues, history of local recurrence, and older age [4]. Metastases can occur via lymphatic spread to regional lymph nodes and hematogeneous spread to liver, lungs and bones.

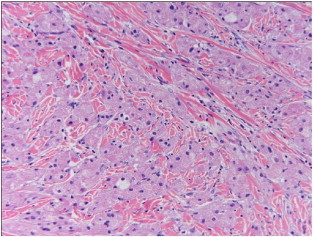

Microscopically, GCTs are composed of loosely infiltrating sheets or clusters of large round or polygonal spindled cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm with intracytoplasmic granules (Fig. 2). The granules typically stain positive on periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stain with diastase-resistant pattern. The nuclei are characteristically uniformly small and centrally located. GCTs are poorly circumscribed. Pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia of the overlying stratified squamous epithelium is commonly seen in many cutaneous lesions, and this may be incorrectly diagnosed as squamous cell carcinoma [1]. The resection margins should be adequate to prevent a misdiagnosis. Recurrence is more likely if the edge of a GCT had an infiltrative and ill-defined pattern, as compared to one with nodular and distinct edges, even with negative margins [4]. However, in a case series of GCTs in the musculoskeletal system by Rose et al., resection margins or depth of tumor had no correlation with the risk of malignancy or recurrence [10].

Fig. 2.

Tumor cells are large and polygonal with abundant eosinophilic granular cytoplasm and small nuclei.

In 1998, Fanburg-Smith et al. proposed six histologic criteria (necrosis, spindling, vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli, increased mitotic activity, high nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio and pleomorphism) for the classification of granular cell tumors into benign (none of the criteria or focal pleomorphism), atypical (1–2 criteria) and malignant (3–6 criteria) forms. They also found that granular cell tumor are tested positive for immunochemical staining for S-100 proteins (98%), vimentin and (100%) neuron-specific enolase (98%). The proliferation-index with Ki67 and immunostaining for p53 overexpression were significantly higher in atypical and malignant tumors as compared to benign tumors [6]. In this report, the atypical and benign tumors were not associated with metastases or mortality. Ultrastructural features that were typical of malignancy included engorgement of the cytoplasm with complex granules and a distinct nuclear pleomorphism.

GCTs may be difficult to distinguish from granular cell variants of basal cell carcinoma, melanoma, leiomyoma, leiomyosarcoma, dermatofibrosarcoma, angiosarcoma, fibrous histiocytoma, and ameloblastoma if examined with routine light microscopy alone. Immunochemical stains will help to distinguish it from other differential diagnoses as it stains negative for desmin, cytokeratins, epithelial membrane antigen and glial fibrillary acidic protein.

Local surgical excision, if complete, is curative for benign GCT. If resection margins are involved, wider local excision may be recommended to decrease the risk of recurrence [4]. Surgery remains the primary therapy for GCTs. Malignant GCTs have a poor response to radiotherapy and chemotherapy. In such cases, treatment with radical local surgery with a view for regional lymph node dissection should be carried out, if there are no distant metastases.

Conclusion

Although GCTs of the vulva are uncommon and mostly benign, they have a tendency for local recurrence. Some of these cases may be multicentric at presentation, so during follow-up, extragenital areas, such as oral cavity and trunk, should be evaluated. In rare cases metastases or malignant transformation can occur. Wide local excision is the treatment of choice. Hence it is important that gynecologists and pathologists are aware of the clinical presentation and histopathology of this condition for appropriate management, counseling and follow-up.

Consent

IRB approval for waiver of informed consent was obtained for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the IRB approval is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors have no conflicts of interests. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this paper.

References

- 1.Horowitz I.R., Copas P., Majmurdar B. Granular cell tumors of the vulva. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1995;173:1710–1714. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90414-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brooks G.G. Granular cell myoblastoma of the vulva in a 6-year-old girl. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 1985;153(8):897–898. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(85)90702-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Abrikossoff A. Uber Myome ansgehend yon der guergestreit'ten willkuerlichen muslkulamr. Virchows Arch. A Pathol. Anat. Histopathol. 1926;260:215–233. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Althausen A.M., Kowalski D.P., Ludwig M.E., Curry S.L., Greene J.F. Granular cell tumors: a new clinically important histologic finding. Gynecol. Oncol. 2000;77:310–313. doi: 10.1006/gyno.2000.5767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Schmidt O., Fleckenstein G.H., Gunawan B., Fuzesi L., Emons G. Recurrence and rapid metastasis formation of a granular cell tumor of the vulva. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 2003;106:219–221. doi: 10.1016/s0301-2115(02)00165-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fanburg-Smith J.C., Meis-Kindblom J.M. Malignant granular cell tumor of soft tissue: diagnostic criteria and clinicopathologic correlation. Am. J. Surg. Pathol. 1998;22:779–794. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199807000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Argenyi Z.B. World Health Organization Classification of Tumours. IARC Press; Lyon: 2006. Granular cell tumour; pp. 274–275. (Pathology and Genetics of Skin Tumours). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majmudar B., Castellano P.Z., Wilson R.W., Siegel R.J. Granular cell tumors of the vulva. J. Reprod. Med. 1990;35(11):1008–1014. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Simone J., Schneider G.T., Begneaud W., Harms K. Granular cell tumor of the vulva: literature review and case report. J. La. State Med. Soc. 1996;148:539–541. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rose B., Tamvakopoulos G.S., Yeung E., Pollock R., Skinner J., Briggs T., Cannon S. Granular cell tumours: a rare entity in the musculoskeletal system. Sarcoma. 2009;2009:765927. doi: 10.1155/2009/765927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]