Key Points

Acquisition of high angiogenesis-inducing capacity by human and murine macrophages requires their polarization toward the M2 phenotype.

M2-polarized macrophages shutdown their TIMP1 gene expression and initiate production of highly angiogenic TIMP-deficient proMMP-9.

Abstract

A proangiogenic function of tissue-infiltrating monocytes/macrophages has long been attributed to their matrix metalloproteinase-9 zymogen (proMMP-9). Herein, we evaluated the capacity of human monocytes, mature M0 macrophages, and M1- and M2-polarized macrophages to induce proMMP-9-mediated angiogenesis. Only M2 macrophages induced angiogenesis at levels comparable with highly angiogenic neutrophils previously shown to release their proMMP-9 in a unique form, free of tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 (TIMP-1). Macrophage differentiation was accompanied by induction of low-angiogenic, TIMP-1–encumbered proMMP-9. However, polarization toward the M2, but not the M1 phenotype, caused a substantial downregulation of TIMP-1 expression, resulting in production of angiogenic, TIMP-deficient proMMP-9. Correspondingly, the angiogenic potency of M2 proMMP-9 was lost after its complexing with TIMP-1, whereas TIMP-1 silencing in M0/M1 macrophages rendered them both angiogenic. Similar to human cells, murine bone marrow–derived M2 macrophages also shut down their TIMP-1 expression and produced proMMP-9 unencumbered by TIMP-1. Providing proof that angiogenic capacity of murine M2 macrophages depended on their TIMP-free proMMP-9, Mmp9-null M2 macrophages were nonangiogenic, although their TIMP-1 was severely downregulated. Our study provides a unifying molecular mechanism for high angiogenic capacity of TIMP-free proMMP-9 that would be uniquely produced in a pathophysiological microenvironment by influxing neutrophils and/or M2 polarized macrophages.

Introduction

A strong link has been established between infiltrating leukocytes and various pathophysiological conditions involving tissue remodeling and transformation.1-3 The leukocyte infiltrate can be represented by hematopoietic cells of different lineages, including lymphocytes, granulocytes, and macrophages. Tumor-associated macrophages (TAMs) have been implicated in cancer progression,4,5 and high numbers of TAMs have been linked to poor prognosis in certain human malignancies.6,7 A remarkable plasticity of macrophages allows them to acquire functionally distinct phenotypes.8,9 Two major alternative phenotypes, namely M1 and M2, have been ascribed to tumor-suppressing and tumor-promoting TAMs, respectively, although a spectrum of activation states has been demonstrated in several settings.10-13 In general, M1 macrophages are associated with an induction of strong immune response and tumoricidal activity. In contrast, M2 macrophages appear to suppress immune surveillance and enhance neovascularization.

Macrophage-induced angiogenesis involves an angiogenic switch,14,15 which is triggered by proteolytic release of direct-acting angiogenic growth factors by the activated zymogen of matrix metalloproteinase-9 (proMMP-9) supplied by infiltrating macrophages.16,17 In Mmp9-null hosts, a lack of proMMP-9 expression prevents the angiogenic switch and significantly reduces angiogenesis and metastasis.16,18 Similarly, biochemical inhibition of overall MMP-9 activity also severely reduced levels of angiogenesis.17 However, both the angiogenic switch and ensuing angiogenesis are not universally attributed to macrophages and macrophage-produced proMMP-9. Studies have indicated that angiogenesis-triggering proMMP-9 could be produced by diverse inflammatory leukocyte types often represented by granulocytes.19-23

Accumulated evidence demonstrates that among granulocytic leukocytes, the neutrophils constitute a critical myeloid cell type delivering angiogenesis-inducing proMMP-9.24-30 The high angiogenic potential of neutrophil proMMP-9 has been linked to its unique tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinase (TIMP)-free status.31 Because neutrophils do not express TIMP-1, the natural inhibitor of MMP-9 enzyme and negative regulator of proMMP-9 activation,32 neutrophil proMMP-9 is released unencumbered by TIMP-1.33 Therefore, TIMP-free neutrophil proMMP-9 can be rapidly activated in the tissue microenvironment and proteolytically release matrix-sequestered angiogenic factors such as vascular endothelial growth factor and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2.34

The possible delivery of MMP-9 has also been attributed to M2-skewed TAMs, shown to express elevated levels of proMMP-9 compared with other subsets of macrophages.35-38 However, although tumor vascularization was linked to the presence of M2-like TAMs,38-40 no evidence was presented to prove unequivocally that angiogenesis-inducing capacity of M2-polarized macrophages depended on their production of MMP-9. This deficiency in direct experimental evidence for proangiogenic functions of MMP-9 secreted by M2 macrophages has triggered the present comparative and quantitative investigation of angiogenesis-inducing capabilities of human and murine macrophages and their secreted proMMP-9.

Herein, we examined the capacity of human monocytes, monocyte-derived mature macrophages (M0 phenotype), and polarized macrophages of M1 and M2 phenotypes to induce in vivo angiogenesis and demonstrated that only M2 macrophages approach the high angiogenic capability of neutrophils. Furthermore, we determined that the angiogenic capacity of M2 macrophages critically depends on production of the readily activatable proenzyme proMMP-9, because M2 polarization is surprisingly accompanied by a substantial downregulation of TIMP-1. Finally, comparative analysis of murine bone marrow (BM)-derived macrophages demonstrated that murine M2 macrophages also shut down their TIMP-1 production and initiate secretion of angiogenic, TIMP-1–deficient proMMP-9. Importantly, Mmp9-null M2 macrophages were low to nonangiogenic, yet did downregulate their, TIMP-1, confirming the critical dependence of angiogenesis induced by M2 macrophages first, on their secreted proMMP-9, and second, on the biochemical status of the proenzyme. Together, our data indicate that the production of TIMP-deficient proMMP-9 could underlie a unifying molecular mechanism determining the high angiogenic potency of proMMP-9 delivered to inflamed tissues by neutrophils and/or M2-polarized macrophages.

Materials and methods

Isolation of neutrophils and monocytes from human peripheral blood

Peripheral blood was collected from healthy donors according to The Scripps Research Institute (TSRI) protocol approved by the Institutional Review Board. Informed consent was obtained in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. The neutrophil and monocytic fractions were isolated as described in supplemental Data on the Blood Web site.

Macrophage differentiation and polarization

Purified monocytes were plated on fetal bovine serum (FBS)-coated surfaces at 1 × 105 cells/cm2 in RPMI 1640/20% FBS plus 100 ng/mL macrophage–colony-stimulating factor (M-CSF; eBioscience) for 7 days to differentiate into M0 macrophages. M1 polarization was induced by 100 ng/mL lipopolysaccharide (LPS; Sigma) and 20 ng/mL interferon (IFN)γ (eBioscience); M2 polarization was induced by 20 ng/mL of recombinant human interleukin (IL)-4, IL-10, or IL-13 (all from eBioscience).

Murine BM-derived macrophage isolation and polarization

BM was flushed from femurs and tibia of wild-type (WT) C57BL/6 mice (TSRI breeding colony) or Mmp9-null mice on C57BL/6 background (Jackson Laboratories). BM cells were cultured in RPMI 1640 containing 10% FBS, 50 nM β-mercaptoethanol, and 10% conditioned medium (CM) from L929 fibrosarcoma cells, a rich source of M-CSF.41 Medium was changed every 2 to 3 days to generate mature M0 macrophages. On day 7, M1 phenotype was induced by 100 ng/mL LPS/20 ng/mL IFNγ, whereas M2-polarization by 20 ng/mL recombinant murine IL-4 (Peprotech).

Cell marker analyses

Isolated human neutrophils and monocytes and cultured macrophages were immunostained for macrophage mannose receptor (MMR; CD206) with mouse monoclonal antibody (mAb; clone 15-2; Biolegend) and analyzed by flow cytometry and immunocytochemistry. Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analyses were conducted for CD80, CD86, and CD181 (supplemental Data). Murine BM-derived macrophages were stained for MMR (clone C068C2; Biolegend) and F4/80 (clone BM8; Biolegend). Expression of α-arginase-1 and inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS) was analyzed by western blotting, respectively, with primary rabbit Ab AV45673 (Sigma) and goat Ab sc-18351 (Santa Cruz), both recognizing human and murine proteins.

Angiogenesis in live animals

All experimental procedures involving live animals were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of TSRI.

Chick embryo angiogenesis model

The assay was performed as described previously.31,34 Tested cells and ingredients were incorporated into 2.1 mg/mL type I collagen (BD Biosciences) at concentrations indicated in the text. Thirty-microliter collagen droplets were polymerized over 2 meshes, generating 3-dimensional (3D) onplants that were grafted onto the chorioallantoic membrane (CAM) of chick embryos. The levels of angiogenesis were determined 3 days later as the ratio of grids with newly formed blood vessels vs total number of grids. Where indicated, specific anti-human MMP-9 mAbs 7-11C (activation-blocking) and 8-3H (nonblocking) were incorporated at 2 µg/mL.

Mouse angiogenesis model

The assay was performed as described previously.28,34,42 Briefly, M0, M1, or M2 macrophages were incorporated at 1.5 × 106 cells/mL into 2.5 mg/mL collagen. Negative control contained no cells. Collagen mixtures (∼50 µL) were polymerized within ∼1-cm-long silicon tubes (angiotubes) and implanted subsequently into SCID mice. The levels of angiogenesis were determined 12 to 14 days later. The angiotubes were excised and their contents were flushed and lysed in 200 µL of 0.2% Triton X-100. The levels of angiogenesis determined using the endothelial marker CD31 correlate closely with the levels determined by measurement of hemoglobin content,28 the approach commonly used in the Matrigel plug angiogenesis model.43 The hemoglobin concentration was determined with QuantiChrom Hemoglobin Kit (BioAssay Systems) and used as a measurement of angiogenesis in the individual angiotubes.

Data analysis and statistics

Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Software (San Diego, CA). Data are presented as means ± standard error of the mean (SEM; bar graphs) or medians (scattergrams) from a representative experiment or several normalized experiments, in which fold changes were calculated from the pooled fold differences by taking ratios of numerical values for individual measurements in experimental groups over the mean of control group. The unpaired 2-tailed Student t test or Mann-Whitney test was used to determine significance (P < .05) in difference between data sets.

Purification of proMMP-9 by gelatin-Sepharose affinity chromatography, proMMP-9 complexing with TIMP-1, zymography, silver staining, gene expression analysis, and gene silencing

The details of these procedures are described in supplemental Data.

Results

Differentiation of human peripheral blood monocytes into mature M0 macrophages and macrophage polarization into M1 and M2 phenotypes

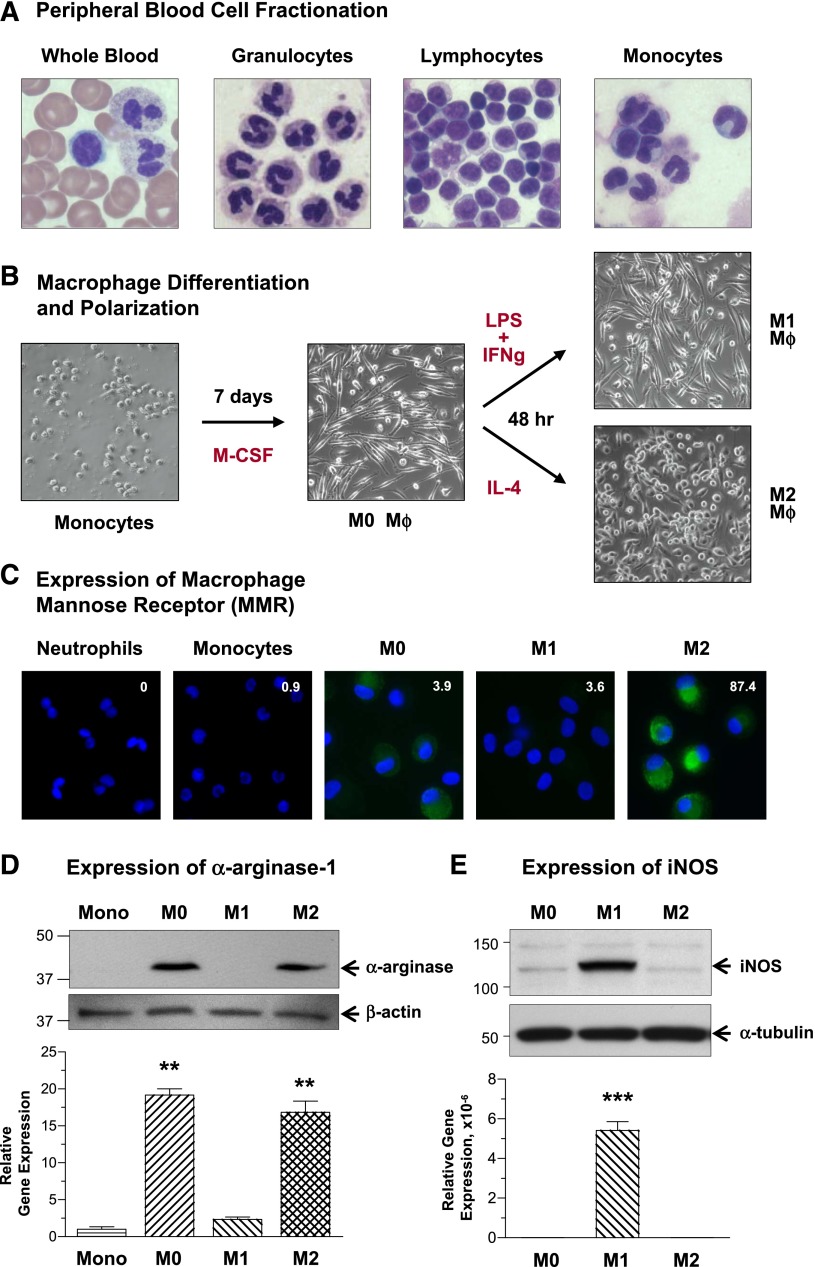

Fractions of granulocytes and mononuclear cells were isolated from human peripheral blood. Granulocytic fraction was represented mostly by neutrophils (97-99%), and further separation of the mononuclear cells resulted in highly purified fractions of lymphocytes (96-99%) and monocytes (92-98%) (Figure 1A).

Figure 1.

Maturation and polarization of human macrophages and expression of characteristic M1 and M2 markers. (A) Isolation of distinct cell populations from peripheral blood. Granulocytes, monocytes, and lymphocytes were fractionated from peripheral blood of healthy donors. Smears of whole blood and isolated cells were stained to analyze the purity of distinct cell populations. The representative images of stained cells demonstrate high purity fractions of neutrophils (97-99% of granulocytic fraction), lymphocytes (96-99%), and monocytes (92-98%). Images were acquired using an Olympus BX60 microscope (Olympus America, Melville, NY), equipped with a digital DVC video camera and high-performance ImageJ plugin acquisition software (DVC Company, Austin, TX), and processed using Adobe Photoshop. Objective lens, ×40. (B) Maturation and polarization of macrophages. Purified monocytes were incubated for 7 days with M-CSF to differentiate into mature macrophages (M0 phenotype). The M0 macrophages were then polarized for additional 2 days into M1 macrophages by substituting M-CSF for a mixture of LPS and IFNγ and into M2 macrophages by stimulation with IL-4. Note the changes in morphology of rounded, loosely adherent monocytes to elongated, firmly adherent M0 macrophages, which retained their M0 morphology being polarized into M1 macrophages and become more rounded and less adhesive after M2 polarization. Phase contrast images were acquired using an Olympus CKX-41 microscope equipped with Olympus U-LS30-3 video camera (Olympus America, Center Valley, PA) and Infinity Capture software (Lumenera, Ottawa, Canada), and processed using Adobe Photoshop. Objective lens, 20×. (C) Analysis of MMR expression. Immunocytochemical staining was performed for MMR (CD206) on permeabilized cells to visualize both cell surface and intracellular pools of the protein. The staining indicates that MMR (green) is not detectable in freshly isolated neutrophils and monocytes. MMR expression is moderately induced during differentiation of monocytes into M0 macrophages but is inhibited during polarization into M1 macrophages. In contrast, M2 polarization is accompanied by substantial increase in the levels of MMR expression. Cell nuclei were stained with 4,6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Images were acquired using a Carl Zeiss AxioImager M1m microscope equipped with AxioVision Re.4.6 software (Carl Zeiss Microscopy, Thornwood, NY) and processed using Adobe Photoshop. Objective lens, ×40. Inserted numerical data represent the levels of cell surface expression of MMR as determined by flow cytometry. Indicated is mean fluorescence intensity determined after subtraction of nonspecific values for mouse IgG. (D) Analysis of α-arginase-1 expression. (Upper) Western blot analysis for α-arginase-1 was conducted on cell lysates separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate-polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) under reducing conditions (40 µg protein per lane). The 38-kDa α-arginase-1 is detectable in M0 and M2 macrophages. (Lower) The blot was reprobed for β-actin (42 kDa) to provide a loading control. Position of molecular weight markers in kilodaltons is indicated on the left. Bar graph, analysis of ARG1 gene expression. Quantitative analysis of ARG1 was performed on mRNA preparations isolated from monocytes and macrophages in comparison with the corresponding levels of housekeeping genes GAPDH and ACTB. Gene expression levels were determined relative to monocytes (1.0). Both protein and gene expression analyses indicate that α-arginase-1 expression is induced during maturation of macrophages from arginase-negative monocytes and is dramatically inhibited during M0 macrophage polarization into the M1, but not M2, phenotype. (E) Analysis of iNOS expression. (Upper) Cell lysates from mature and polarized macrophages (20 µg per lane) were analyzed for iNOS by western blotting under reducing conditions, confirming the induction of 130-kDa iNOS in M2 macrophages. (Lower) The blot was reprobed for α-tubulin (Biolegend) to provide equal loading control. Position of molecular weight markers in kilodaltons is indicated on the left. Bar graph, analysis of NOS2 gene expression. Quantitative analysis of NOS2 was performed on mRNA preparations isolated from macrophages in comparison with the corresponding levels of β-actin. Gene expression levels were determined relative to M0 macrophages (1.0). Both protein and gene expression analyses indicate that iNOS expression is induced during polarization of M0 macrophages toward the M1, but not M2, phenotype.

To induce differentiation into macrophages, monocytes were incubated in the presence of M-CSF (Figure 1B). During a 7-day differentiation, monocytic cells become larger and more flattened. Mature M0 macrophages were then polarized into M1 macrophages or M2 macrophages by induction with LPS/IFN-γ or IL-4, respectively. Although polarization into the M1 phenotype did not cause major changes in cell morphology, polarization toward the M2 phenotype yielded more rounded and loosely attached cells (Figure 1B).

Immunocytochemical staining, highlighting mainly the intracellular protein pool, demonstrated that the MMR, CD206, undetectable in purified neutrophils and monocytes, was marginally induced in M0 macrophages, suppressed during M1 polarization, but significantly elevated in M2 macrophages (Figure 1C). Flow cytometry indicated that only M2 macrophages expressed high levels of MMR on their cell surface (mean fluorescence intensity data in Figure 1C and supplemental Table 1). Differentiation of monocytes into M0 macrophages was accompanied by induction of α-arginase-1, which became undetectable during M1 polarization while remaining unaffected in M2 macrophages (Figure 1D, upper). The expression pattern of α-arginase-1 protein closely matched that of the ARG1 gene (Figure 1D, bar graph). Western blot and gene expression analyses indicated that M1 polarization was accompanied by induction of NOS2 and its encoded protein, iNOS (Figure 1E). Monocytes and M0, M1, and M2 macrophages were also analyzed for several myeloid cell surface markers, including CD80, CD86, and CD181 (CXCR1) by flow cytometry (supplemental Table 1), demonstrating variable levels of induction in all 3 types of macrophages.

Together, our biochemical and marker analyses confirmed proper phenotypes of differentiated and polarized macrophages and validated their further comparisons in critical in vivo functional assays.

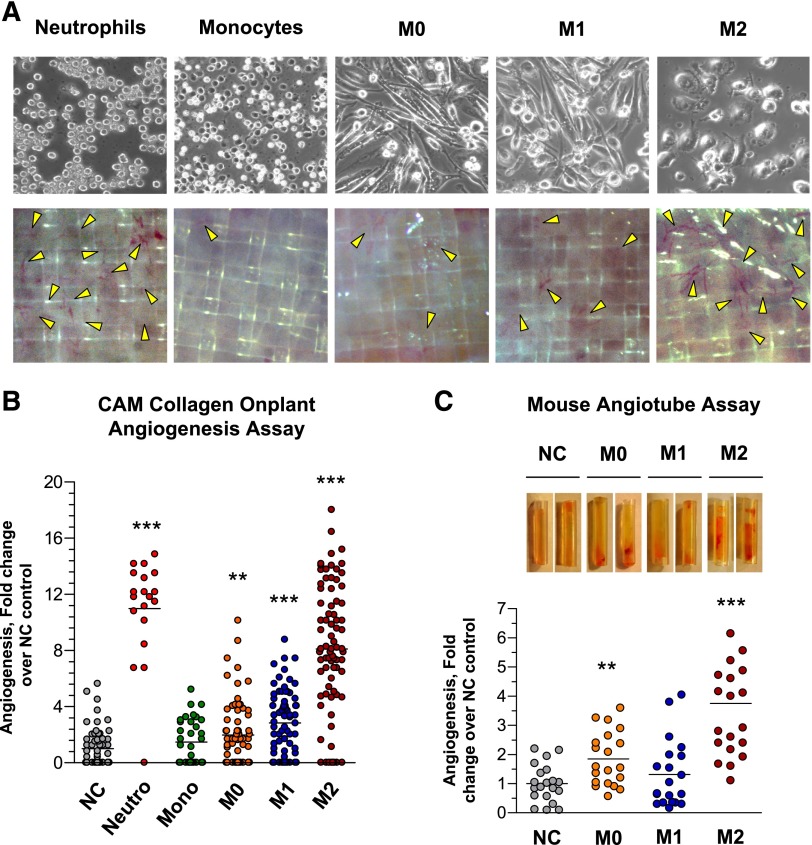

In vivo angiogenic potential of neutrophilic and monocytic leukocytes

The live chick embryo model44 was used to compare the angiogenic potentials of neutrophils, monocytes, and macrophages of M0, M1, and M2 phenotypes (Figure 2A, upper). Collagen onplants, containing 1.5 × 104 cells of each type, were grafted on the CAM. Microscopic evaluation indicated high levels of angiogenesis induced by intact neutrophils and M2 macrophages (Figure 2A, lower). Quantitative analyses confirmed that neutrophils and M2 macrophages induced the highest levels of angiogenesis (∼8- to 12-fold over no-cell control), whereas undifferentiated monocytes yielded angiogenesis that barely exceeded background levels and M0/M1 macrophages exhibited low to moderate angiogenesis-inducing abilities (Figure 2B).

Figure 2.

Comparative analysis of angiogenic capabilities of human neutrophils, monocytes, and mature and polarized macrophages. (A) Angiogenic potential of intact leukocytes in the in vivo CAM angiogenesis model. (Upper) Freshly purified neutrophils and monocytes, and macrophages of M0, M1, and M2 phenotypes were incorporated into 2-tier gridded 3D collagen onplants (3 × 104cells/onplant), which were grafted on the CAM of chick embryos. Images were acquired using an Olympus CKX-41 microscope equipped with Olympus U-LS30-3 video camera and Infinity Capture software and processed using Adobe Photoshop. Objective lens, ×20. (Lower) After 76 hours of incubation, the onplants were scored for the presence of newly developed angiogenic vessels distinctly localized above the plane of the lower mesh grids (yellow arrowheads). Images were acquired using an Olympus binocular microscope SZ-PT (Olympus America, Melville, NY) equipped with a DVC video camera and high-performance ImageJ plugin acquisition software. Objective lens, 10×. (B) Angiogenesis-inducing capability of intact cells. The levels of angiogenesis were quantified for individual onplants as a ratio of grids containing new blood vessels to total number of scored grids, providing an angiogenic index. From 4 to 6 embryos, each grafted with 6 collagen onplants, were analyzed in 3 independent experiments. Scattergram presents fold changes in the levels of angiogenesis compared with negative no-cell (NC) control (1.0). Lines represent means of fold changes in angiogenic indices. **P < .01; ***P < .0001. (C) Comparative analysis of mature and polarized macrophages in the mouse angiotube model. Intact viable M0, M1, and M2 macrophages were incorporated into 2.5 mg/mL native collagen at 2 × 106 cells/mL. Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) was used as a negative, no-cell control (NC). Collagen mixtures were polymerized in the ∼1-cm-long tubes (angiotubes), which were surgically implanted under the skin of immunodeficient mice. The angiotubes were excised from the mice 12 to 14 days after implantation (images on the top). The contents of angiotubes were lysed in equal volumes of lysing buffer and hemoglobin concentration was determined, providing measurements of angiogenesis-inducing capacity of tested cells. Scattergram presents fold changes in the levels of angiogenesis induced by different macrophage types compared with negative NC control (1.0). Lines represent means of fold changes. Shown is a representative experiment from 2 independent experiments, each using from 4 to 5 mice, each implanted with 4 angiotubes. **P < .01; ***P < .0001, between the means from the experimental groups vs NC control.

To verify that the angiogenic differential manifested by macrophages was not restricted to the avian system, we used a quantitative mouse angiogenesis assay.28,34,42 Similar to the CAM model, M2 macrophages in the murine system induced highest levels of angiogenesis compared with M0 or M1 macrophages as indicated by the appearance of angiotubes (Figure 2C, upper) and quantification of their hemoglobin content (Figure 2C, scattergram). These data show that polarization of macrophages into the M2 phenotype is accompanied by a substantial increase of their angiogenesis-inducing capacity.

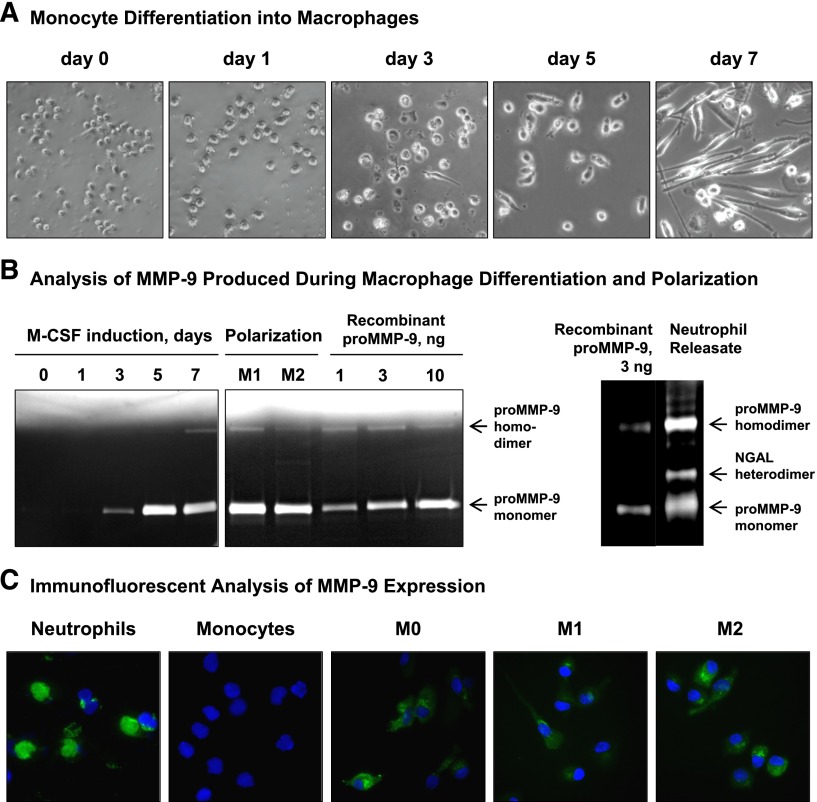

MMP-9 expression during monocyte differentiation into M0 macrophages and their polarization into M1 and M2 phenotypes

Because high angiogenic potential of neutrophils has been associated with their prestored proMMP-9,31,34 we tested whether the angiogenic potentials of different types of macrophages are attributed to their secreted proMMP-9. We initially investigated the kinetics of proMMP-9 expression during macrophage differentiation and polarization. During a 7-day maturation, monocytes morphologically change from loosely attached round cells to more firmly anchored mature macrophages (Figure 3A). Production of proMMP-9 was induced by day 3 and reached the highest levels between days 5 and 7 (Figure 3B, left), and was not significantly affected by M1 or M2 polarization (Figure 3B, middle). Analysis of MMP-9 species produced by macrophages vs neutrophils indicated that in contrast to 3 distinct forms characteristic of neutrophil proMMP-9 (Figure 3B, right), the majority of macrophage proMMP-9 was represented by monomers with some dimer formation. Quantification of cell production of proMMP-9 against known amounts of recombinant human MMP-9 in the same gels indicates that during 30- to 60-min degranulation, neutrophils can release 1 to 2 µg of prestored proMMP-9 per 1 × 106 cells, whereas mature M0 macropages and polarized M1 and M2 macrophages require 48 hours to secrete 0.5 to 5 µg per 1 × 106 cells (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 1A). This unique potency of neutrophils in supplying readily available proMMP-9 is further emphasized by immunofluorescent staining demonstrating that, although M0, M1, and M2 macrophages are MMP-9 positive, the neutrophils are loaded with large cargo of MMP-9 (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Induction of proMMP-9 during maturation and polarization of human macrophages. (A) Morphological changes during monocytes differentiation into macrophages. Freshly isolated monocytes were incubated in the presence of M-CSF for 7 days. Note a gradual change in the morphology from rounded monocytes to elongated cells, first noticeable on day 3 and representing almost all M0 macrophages by day 7. Images were acquired using an Olympus CKX-41 microscope equipped with Olympus U-LS30-3 video camera and Infinity Capture software and processed using Adobe Photoshop. Objective lens, ×20. (B) Kinetic analysis of proMMP-9 production during macrophage maturation and polarization. (Left) Gelatin zymography was conducted on serum-free (SF) medium conditioned by 2 × 104 human monocytes cultured in the presence of M-CSF for 7 days and then polarized into M1- or M2 macrophages. The position of 92-kDa proMMP-9 monomer and ∼200-kDa homodimer is indicated on the right. Human recombinant proMMP-9 was loaded to provide the means of quantification of proMMP-9 production. (Right) Zymographic analysis of granule contents released by 1 × 104 neutrophils. The position of 92-kDa proMMP-9 monomer, 125-kDa NGAL heterodimer, and ∼200-kDa homodimer is indicated on the right. Human recombinant proMMP-9 (3 ng per lane) was run to estimate the MMP-9 load in neutrophils. (C) Immunofluorescent analysis of MMP-9 expression in isolated neutrophils and monocytes and mature and polarized macrophages. Macrophages were differentiated from monocytes cultured on coverslips, whereas purified neutrophils and monocytes were directly placed on coverslips after cell isolation. The cells were fixed and then stained for human MMP-9 with mAb 8-3H (green). Cell nuclei were contrasted with 4′6 diamidino-2-phenylindole (blue). Images were acquired using a Carl Zeiss AxioImager M1m microscope equipped with AxioVision Re.4.6 software and processed using Adobe Photoshop. Objective lens, ×40.

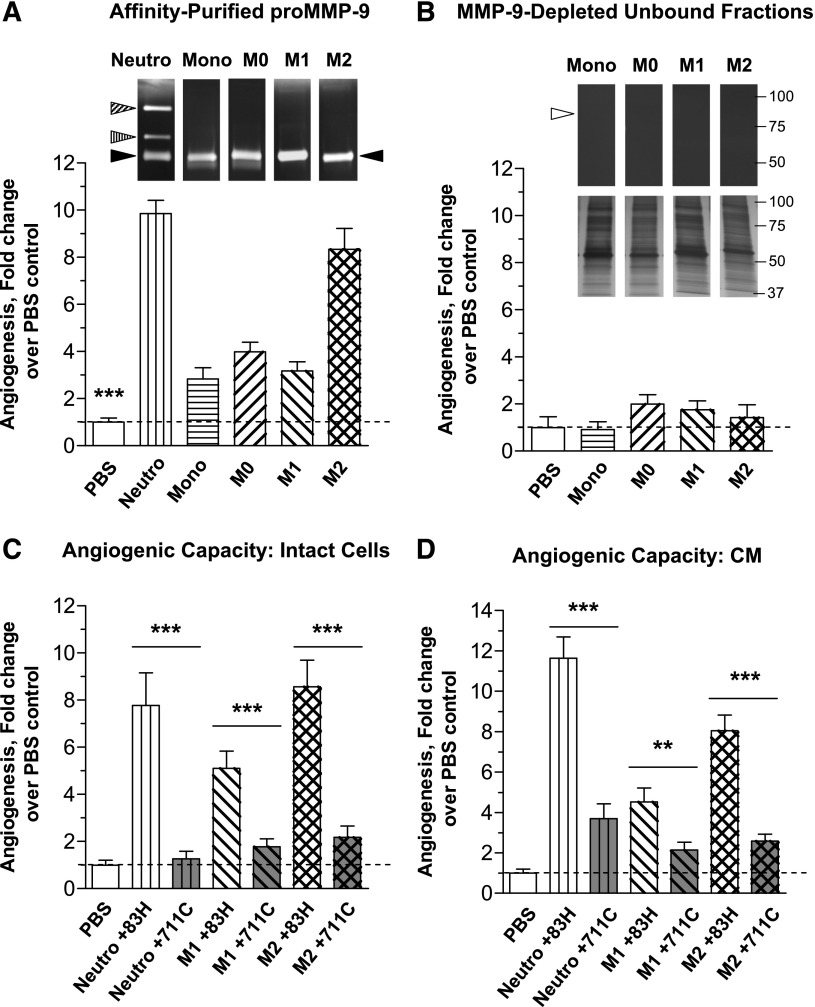

Secreted proMMP-9 is responsible for angiogenic capacity of mature and polarized macrophages

Using gelatin-Sepharose affinity chromatography, we isolated proMMP-9 from 30-minute neutrophil releasate and from 48-hour CM of monocytes and M0, M1, and M2 macrophages and confirmed that all monocytic cell types secrete mainly the 92-kDa proenzyme monomer (supplemental Figure 1B). To characterize the angiogenic potential of proMMP-9 produced by the different leukocytes, purified proMMP-9 was incorporated into collagen onplants at the same concentration of 1.1 nM (100 ng/mL; 3 ng per onplant) (Figure 4A, inset). Quantification of angiogenesis demonstrated that proMMP-9 produced by neutrophils and M2 macrophages yielded the highest levels of angiogenesis (Figure 4A, bar graph). In contrast, proMMP-9 produced by monocytes as well as from M0 and M1 macrophages induced relatively low levels of angiogenesis, even though equal amounts of proMMP-9 purified from different cell types were used. To evaluate the putative contribution to angiogenesis of secreted proteins other than proMMP-9, we tested the gelatin-unbound fractions, which exhibited little or no zymography-detectable proMMP-9 but contained >95% of the total protein produced by the cells (inset in Figure 4B and supplemental Figure 1B). These proMMP-9–depleted fractions were incapable to induce significant angiogenesis (Figure 4B, bar graph), indicating that most of angiogenesis-inducing moiety secreted by macrophages was comprised in their secreted proMMP-9.

Figure 4.

The secreted proMMP-9 and its activation determine angiogenesis-inducing capacity of human monocytes and macrophages. (A) Comparative analysis of angiogenesis-inducing capacity of purified proMMP-9 produced by different cell types. ProMMP-9 released by neutrophils or secreted into SF medium by monocytes or macrophages was purified by affinity chromatography and incorporated into collagen mixture to provide 3 ng proMMP-9 per onplant. Control onplants contained PBS only. (Upper) Zymographic images above the corresponding bars in the graph below indicate equal supplementation of proMMP-9 into the onplants. Triangles indicate positions of the monomer, heterodimer and homodimer of proMMP-9 released by neutrophils (left) and the proMMP-9 monomer secreted by monocytes and macrophages (right). Bar graph, levels of angiogenesis were determined as described in Figure 2B. From 4 to 6 embryos, each grafted with 6 collagen onplants, were analyzed per variable in 3 independent experiments. The pooled data are shown as fold changes (means ± SEM) in the levels of angiogenesis induced by proMMP-9 produced by different cell types compared with PBS control (1.0). Note that, although all tested purified proMMP-9 induced angiogenesis at levels significantly higher than the levels observed in PBS control, equal amounts of proMMP-9 produced by distinct cell types induce different levels of angiogenesis (***P < .0001). (B) The angiogenesis-inducing capacity of the secretate produced by monocytes and macrophages is contained in proMMP-9. (Upper) The flow-through fractions depleted of proMMP-9 by affinity chromatography (compare zymographic images in B and A), but containing >95% of initial protein content (insets from silver-stained gels positioned below zymographic images), were incorporated into collagen onplants at amounts equalized as to being produced by the same number of cells (1.5 × 104/onplant). Open triangle in the zymograph indicates the position where proMMP-9 band would be localized before depletion. Bar graph, levels of angiogenesis were determined 3 days later as described in Figure 2B. The data are from a representative experiment using from 4 to 6 embryos per variant. Bars are means ± SEM of fold-changes in the levels of angiogenesis induced by cell secretates depleted of proMMP-9 compared with PBS control (1.0). (C) Activation of proMMP-9 produced by intact cells is required for induction of angiogenesis. Intact neutrophils and M1 or M2 macrophages were incorporated into collagen onplants (1.5 × 104 cells/onplant), along with 2 µg/mL of either mAb 8-3H, which binds to proMMP-9, but does not block the activation of the proenzyme, or mAb 7-11C, which effectively blocks activation of proMMP-9 into the proteolytically capable MMP-9 enzyme. Control onplants contained PBS only. The levels of angiogenesis were determined as described in Figure 2B. For each variant, from 4 to 6 embryos grafted with 6 collagen onplants were analyzed in 2 independent experiments. The pooled data are shown as fold changes in the levels of angiogenesis induced by different cell types compared with PBS control (1.0). Bars are means ± SEM of fold changes in angiogenic indices. ***P < .0001. (D) Activation of proMMP-9 secreted by macrophages is required for induction of angiogenesis. Neutrophil releasate and SF CM from M1 or M2 macrophages was incorporated into collagen onplants at 1.5 ng of proMMP-9 per onplant along with 2 µg/mL of MMP-9–specific mAbs, namely control mAb 8-3H or activation-blocking mAb 7-11C. Control onplants contained PBS only. The levels of angiogenesis were determined as described in Figure 2B. The data are from a representative experiment using from 4 to 6 embryos per variant. Bars are means ± SEM of fold changes in the levels of angiogenesis induced by CM from different cell types compared with PBS control (1.0). **P < .005; ***P < .0001.

By using mAb 7-11C, uniquely blocking activation of human proMMP-9,31 we determined that generation of MMP-9 enzyme from macrophage-produced zymogen was necessary for induction of angiogenesis. The mAb 7-11C or control, proMMP-9–binding but nonblocking, mAb 8-3H, was incorporated into cell-collagen onplants containing neutrophils or polarized macrophages. In parallel experiments, neutrophil releasates and CM from macrophages were tested instead of intact cells. The anti–MMP-9 mAb 7-11C caused a substantial 80% to 90% reduction of angiogenesis induced by either intact cells (Figure 4C) or their secreted products (Figure 4D). The dramatic inhibition of MMP-9–induced angiogenesis caused by mAb 7-11C allowed us to conclude that the angiogenic potential of neutrophils and polarized macrophages depends on the activation of their proMMP-9 to the catalytically competent MMP-9 enzyme. Furthermore, almost complete reduction of cell-mediated angiogenesis by anti–MMP-9 activation-blocking antibody (Figure 4C) affirms the data in Figure 4B, demonstrating that the majority of in vivo angiogenic capacity of human myeloid cells was contained in their proMMP-9. There may be other angiogenic factors produced by M2 macrophages, but such putative factors appear far less potent than the proMMP-9 secreted by intact cells in vivo (Figure 4C) or in vitro (Figure 4B,D).

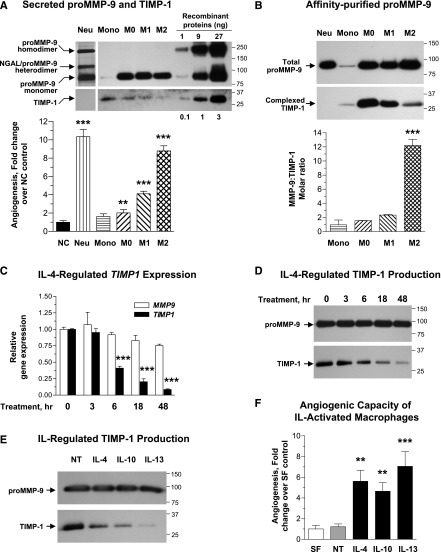

TIMP-1 status of proMMP-9 produced by human monocytes and macrophages

The varying levels of MMP-9–dependent angiogenesis induced by the same amounts of proMMP-9 purified from different inflammatory cell types (Figure 4A) suggested that structural or biochemical differences might determine the angiogenic potency of the secreted proMMP-9. Because high levels of angiogenic capacity of neutrophil proMMP-9 are determined by its TIMP-free status,31,34 we investigated whether relatively low angiogenic potentials of proMMP-9 produced by M0 and M1 macrophages could be attributed to complexed TIMP-1, which would delay activation of MMP-9 zymogen and also reduce catalytic activity of the activated enzyme. Both CM and purified proMMP-9 preparations were analyzed by western blotting to determine correspondingly levels of TIMP-1 produced by different cell types and levels of TIMP-1 tightly bound to purified proMMP-9. The analysis of CM indicated that undifferentiated monocytes secrete the highest levels of TIMP-1 while producing the lowest levels of proMMP-9 (Figure 5A, upper). Differentiation of monocytes into M0 macrophages as well as M1 polarization was accompanied by an overall reduction in TIMP-1 production. Importantly, the lowest amounts of TIMP-1 were secreted by the polarized M2 macrophages. Western blot analyses indicate that 1 × 106 neutrophils release 1 to 2 µg of proMMP-9 within 20 to 30 minutes of induction, whereas macrophages require at least 24 hours to secrete the same amount of proMMP-9 (Figure 5A), corroborating our zymography quantifications (Figure 3B; supplemental Figure 1A).

Figure 5.

M2 polarization of human macrophages downregulates TIMP-1 expression, resulting in production of highly angiogenic TIMP-1–deficient proMMP-9. (A) (Upper) Production of proMMP-9 and TIMP-1 by monocytes and mature and polarized macrophages. Neutrophil releasate from 5 × 103 cells and SF medium conditioned by 2 × 104 monocytic cells was analyzed for MMP-9 and TIMP-1 by western blotting under nonreducing conditions. Following transfer, the membrane was cut into 2 portions, which were probed for MMP-9 (top) and TIMP-1 (bottom). Human recombinant proMMP-9 and TIMP-1 were run at the indicated amounts to provide means for quantification of protein production. Positions of the 92-kDa monomer, 125-kDa heterodimer, and ∼200-kDa homodimer of proMMP-9 and 28-kDa TIMP-1 are indicated on the left. Position of molecular weight markers in kilodaltons is indicated on the right. Bar graph, comparative analysis of angiogenesis-inducing capacity of monocytic cell-conditioned media. SF CM from monocytic cells and neutrophil releasate was incorporated at volumes providing equal amounts of proMMP-9 (3 ng per collagen onplant). From 4 to 6 embryos, each grafted with 6 collagen onplants, were analyzed per variable in 5 independent experiments. Bar graph presents means ± SEM of fold changes in the levels of angiogenesis compared with no-cell control (NC, 1.0). **P < .01; ***P < .0001. (B) (Upper) Analysis of the levels of TIMP-1 naturally complexed with proMMP-9 produced by monocytes and mature and polarized macrophages. ProMMP-9 was purified by affinity chromatography from neutrophil releasate and SF medium conditioned by monocytes or different types of macrophages. Western blot analysis of isolated proMMP-9 preparations was conducted under reducing conditions to determine the amount of TIMP-1 complexed with distinct proMMP-9 preparations. Note that the preparation of neutrophil proMMP-9 is completely devoid of TIMP-1 and that reduction led to collapsing of all neutrophil proMMP-9 forms to the 92-kDa monomer species. Positions of purified proMMP-9 monomer and the complexed 28-kDa TIMP-1 are indicated on the left. Positions of molecular weight markers are indicated on the right. Bar graph, stoichiometric ratio of proMMP-9 to TIMP-1 in purified preparations of proMMP-9 from monocytes and macrophages was calculated based on standard amounts of recombinant proMMP-9 and TIMP-1, which were run in parallel in additional lanes of the same gel (supplemental Figure 1C). ***P < .0001. (C) Gene expression analysis of MMP9 and TIMP1 during IL-4–mediated M2 polarization. M0 macrophages were introduced to 20 ng/mL IL-4, and mRNA was extracted from the cells at the indicated time points. Gene expression was analyzed by quantitative reverse transcriptase-polymerase chain reaction relative to the levels of the corresponding gene (1.0) before addition of IL-4 (0 hours). Presented are data from 1 of 4 independent experiments run in triplicates. ***P < .0001. (D) Western blot analysis of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 secretion during IL-4–mediated M2 polarization. M0 macrophages were introduced to IL-4 for the indicated time (hours) and then switched to SF conditions. Following a 48-hour incubation, the samples of CM were analyzed for MMP-9 and TIMP-1 by western blotting. (E) IL-mediated regulation of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 in M2 macrophages. M0 macrophages were introduced to 20 ng/mL of human IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13, or left nontreated (NT). Following a 24-hour induction, the cells were switched to SF medium, and CM as collected after 48 hours. CM was analyzed for MMP-9 and TIMP-1 by western blotting. Samples of CM were normalized to equal number of cells and processed by SDS PAGE on 4% to 20% gels under reducing conditions. After transferring of separated proteins, the membrane was cut horizontally, and the upper potion probed with anti–MMP-9 antibody and the lower portion with anti–TIMP-1 antibody. The position of the molecular weight markers is indicated on the right. (F) Angiogenic potential of IL-activated macrophages. Angiogenic potency of CM from M0 macrophages induced by different ILs was analyzed in the CAM assy. Data are from 1 of 3 independent experiments, each involving from 4 to 6 chick embryos with 5 to 6 collagen onplants. Bar graph presents means ± SEM of fold changes in the levels of angiogenesis compared with SF control (1.0). **P < .005 and ***P < .0001 in comparison with nontreated (NT) macrophages.

When CM from different monocytic cell types was compared for angiogenic capacity, the levels of angiogenesis inversely correlated with the levels of secreted TIMP-1. Thus, levels of angiogenesis induced by M2-CM were comparable with those induced by neutrophil releasate, whereas CM from monocytes and M0 macrophages induced angiogenesis barely exceeding levels of no-cell control (Figure 5A, bar graph). Importantly, despite identical amounts of proMMP-9, the angiogenic capability of M1-CM was less than half of M2-CM (Figure 5A). Of note, no inhibitory effects on angiogenesis were observed when M0-CM was mixed with M2-CM (supplemental Figure 2), indicating that it is not the secretion of angiogenesis inhibitors by nonangiogenic macrophages but rather the biochemical status of proMMP-9 produced by different types of macrophages that is responsible for the observed angiogenic differentials. These data also indicate that putative free TIMP-1 that might be present in CM from M0-macrophages did not inhibit TIMP-deficient proMMP-9 produced by M2 macrophages.

Because angiogenic capacity and activation rates of proMMP-9 depend on the levels of bound TIMP-1,31,34 we determined the molar ratios of proMMP-9 to TIMP-1 in proMMP-9 produced by different cell types (Figure 5B, upper; supplemental Figure 1C). On average, monocytic proMMP-9 had a proMMP-9:TIMP-1 molar ratio of ≤1.0 (Figure 5B, bar graph), indicating that all proMMP-9 molecules were complexed with TIMP-1. The molar ratios of the proMMP-9:TIMP-1 complexes produced by M0 and M1 macrophages were between 1.4 and 2.0, indicating that only a portion (∼25-50%) of the secreted proMMP-9 molecules was TIMP-1 free. On the other hand, M2 polarization, which results in diminishment of TIMP-1 secretion (Figure 5A), was accompanied by production of a proMMP-9 characterized by substantially reduced levels of bound TIMP-1. Based on densitometry analysis in comparison with recombinant proMMP-9 ladder (supplemental Figure 1C), purified M2 macrophage complexes yielded the highest proMMP-9:TIMP-1 molar ratios, on average reaching 12.1 ± 0.9 (n = 4) (Figure 5B) and indicating that ≥90% of the proMMP-9 molecules secreted by M2 macrophages were TIMP-1 free. Noteworthy, neutrophils produce no TIMP-1 (Figure 5A-B), resulting in TIMP-free status of all their released proMMP-9 molecules and strongly suggesting that specific cytokine-induced TIMP-1 deficiency could be the underlying reason for high angiogenesis-inducing capacity of proMMP-9 produced by M2 macrophages.

To verify that cytokine-mediated M2 polarization was accompanied by downregulation of TIMP-1, we conducted a kinetic analysis of TIMP-1 and MMP-9 expression in IL-4–treated macrophages. Gene expression analysis demonstrated relatively stable levels of MMP9 mRNA during M2 polarization, whereas a significant reduction in TIMP1 expression was observed by 6 hours of IL-4 treatment (Figure 5C), followed by a substantial decrease in TIMP-1 protein within the next 12 to 48 hours of M2 polarization (Figure 5D).

To investigate whether downregulation of TIMP-1 during M2 polarization was unique to IL-4, M0 macrophages were alternatively treated with IL-10 and IL-13, 2 cytokines previously implicated in the induction of the M2 phenotype.1,13,45 Similar to IL-4, both IL-10 and IL-13 sustained the expression of α-arginase-1 and did not induce expression of NOS2 (supplemental Figure 3A). However, IL-10 and IL-13 significantly downregulated the levels of secreted TIMP-1 while not affecting the levels of proMMP-9 (Figure 5E). These data strongly indicate that TIMP-1 downregulation is a general mechanism underlying M2 polarization by different cytokines and not unique to IL-4 treatment. Furthermore, our angiogenesis assays demonstrated that CM from M0 macrophages treated with either IL-10 or IL-13 was highly angiogenic and exhibited angiogenic potency comparable with that of IL-4–polarized M2 macrophages (Figure 5F). Finally, it appears that IL-4–induced shutdown of TIMP-1 during polarization toward the M2 phenotype could be macrophage-specific because it did not occur in other hematopoietic lineages represented by 2 leukemia cell types, HL-60 promyeloblasts and U-937 histiocytes, or in human cancer cells such as HT-1080 fibrosarcoma (supplemental Figure 4).

Together, these data indicate that TIMP-1 downregulation and not the overall upregulation of proMMP-9 may be a general characteristic of M2 macrophage polarization.

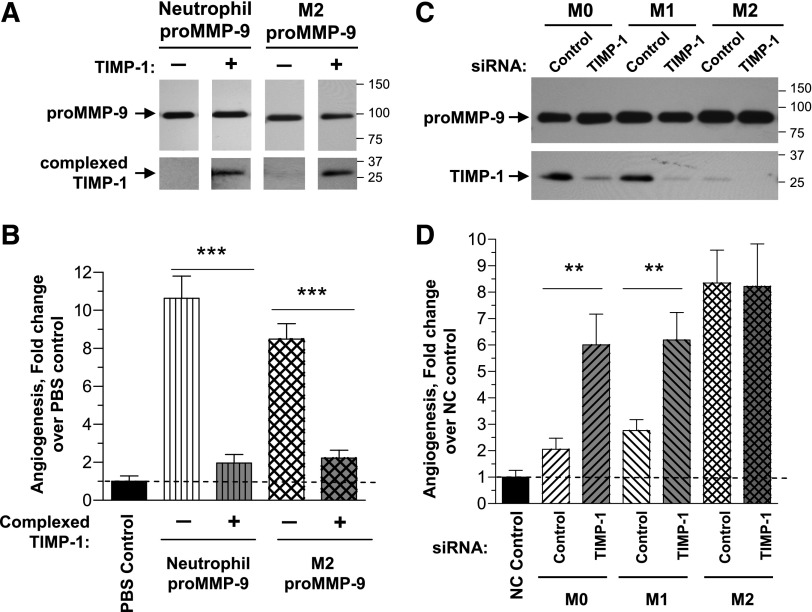

TIMP-1 functionally regulates the angiogenic potential of proMMP-9

To confirm that the bound TIMP-1 determines the high angiogenic potential of proMMP-9 produced by myeloid cells, we stoichiometrically complexed recombinant TIMP-1 with TIMP-free neutrophil proMMP-9 and TIMP-deficient M2 macrophage proMMP-9, and analyzed the angiogenic potential of resulting complexes. Western blot analyses confirmed the efficient, near stoichiometric 1:1 binding of TIMP-1 to neutrophil proMMP-9 and M2 proMMP-9 (Figure 6A). The in vivo angiogenesis results show that the high angiogenic capacity of both neutrophil proMMP-9 and M2 macrophage proMMP-9 was 80% to 90% diminished if their proMMP-9 was stoichiometrically complexed with TIMP-1 (Figure 6B).

Figure 6.

TIMP-1–deficient status determines high angiogenic capacity of proMMP-9 produced by human M2-polarized macrophages. (A) Complexing of neutrophil and M2 macrophage proMMP-9 with TIMP-1. Purified TIMP-free neutrophil proMMP-9 and TIMP-deficient proMMP-9 produced by M2 macrophages was incubated with fivefold molar excess of TIMP-1 and repurified by affinity chromatography on gelatin Sepharose to remove unbound TIMP-1. The original and resulting preparations were analyzed by western blotting for 92-kDa MMP-9 and 28-kDa TIMP-1, confirming efficient complexing of TIMP-1 to proMMP-9. (B) Encumbrance by TIMP-1 abrogates high angiogenesis-inducing capacity of proMMP-9. Preparations of original and TIMP-1–complexed proMMP-9 from neutrophils and M2 macrophages were incorporated into collagen mixtures to provide 3 ng of proMMP-9 per onplant. The levels of angiogenesis were analyzed 3 days later in comparison with PBS control. The data are from a representative experiment performed using from 4 to 6 embryos, each grafted with 6 collagen onplants, per condition. The data are presented as fold changes (means ± SEM) in the levels of angiogenesis induced by different proMMP-9 preparations compared with PBS control (1.0). ***P < .0001. (C) Downregulation of TIMP-1 expression by siRNA treatment. After 7-day differentiation of monocytes into mature M0 macrophages and M0 macrophage polarization into M1 and M2 phenotypes, the cells were transfected with control or TIMP-1 siRNA constructs. CM from siRNA-treated mature M0 and polarized M1 and M2 macrophages was analyzed by western blotting for levels of proMMP-9 and TIMP-1. Note that TIMP-1 siRNA treatment did not affect the levels of proMMP-9 production, but significantly downregulated TIMP-1 expression in M0 and M1 macrophages. (D) Downregulation of TIMP-1 in the TIMP-1–expressing M0 and M2 macrophages induces their angiogenic capacity. Low levels of TIMP-1 expression and production correlates with high levels of angiogenesis induced by mature and polarized macrophages. Mature M0 and polarized M1 and M2 macrophages were treated with control or TIMP-1 siRNA and incorporated into collagen mixtures to provide 1 × 104 cells per collagen onplant. Negative control contained no cells (NC). The data are presented as fold changes (means ± SEM) in the levels of angiogenesis compared with NC control (1.0). Note that significant downregulation of TIMP-1 in M0 and M1 macrophages results in a significant increase of their angiogenic capacity. **P < .01.

To demonstrate that a TIMP-1 burden diminishes angiogenic potential of myeloid proMMP-9, we silenced TIMP1 in M0 mature and M1-polarized macrophages by a small interfering RNA (siRNA) construct, and analyzed angiogenesis-inducing capacity of cells in comparison with M2 macrophages. The treatment of M0 and M1 macrophages with TIMP-1 siRNA resulted in a substantial downregulation of TIMP-1 protein but no significant effects on production of proMMP-9 (Figure 6C). The TIMP-1 siRNA treatment caused no significant effects on angiogenesis induced by the already TIMP-deficient M2 macrophages, confirming that the TIMP-1 siRNA treatment did not cause off-target effects or nonspecifically induce angiogenesis. However, the suppression of TIMP-1 expression in M0 and M1 macrophages caused a substantial, three- to fivefold increase in their ability to induce angiogenesis (Figure 6D).

Together, these findings indicate that within inflamed tissues, a high molar ratio of angiogenic proMMP-9 to antiangiogenic TIMP-1 would be crucial during new blood vessel formation induced by polarized macrophages.

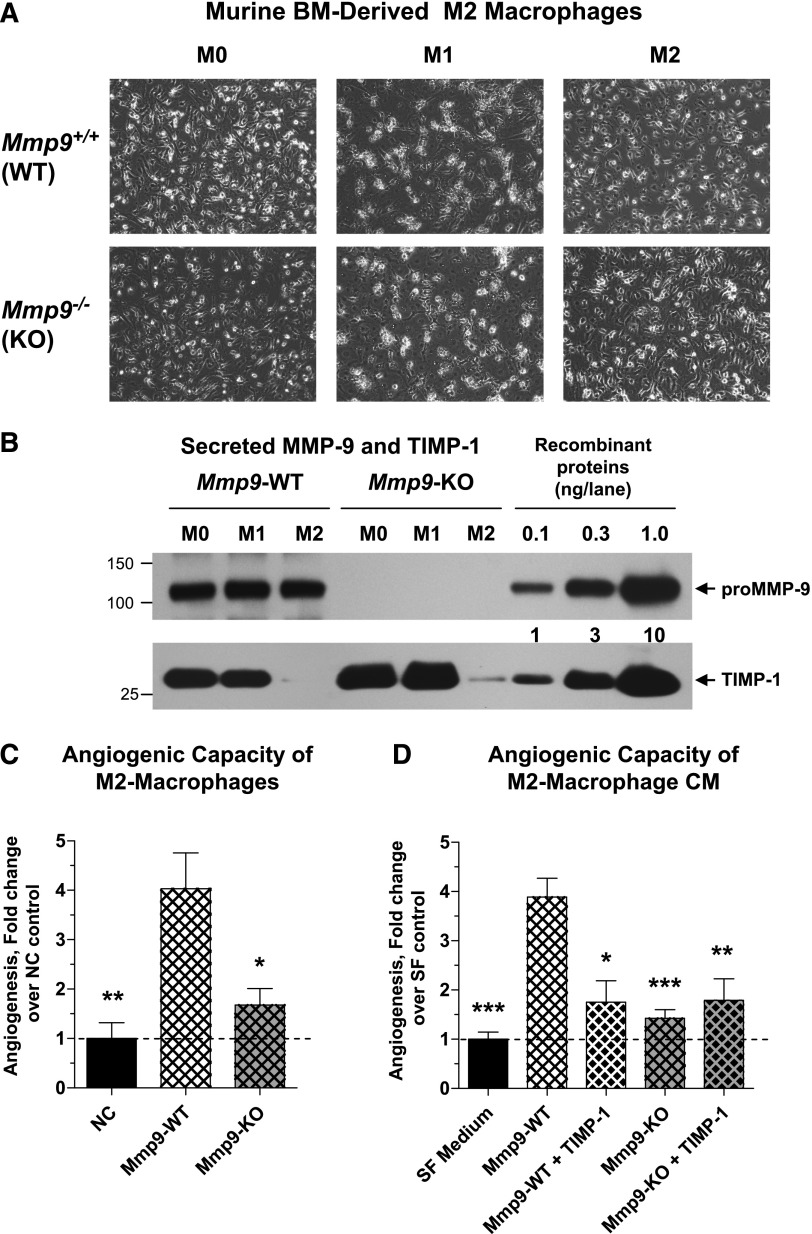

Angiogenic potential of murine BM-derived macrophages depends on their TIMP-deficient proMMP-9

To corroborate our findings regarding angiogenic properties of human M2 macrophages and M2-derived proMMP-9, we conducted a study of the angiogenic potential of murine macrophages. BM cells were isolated from WT or Mmp9-knockout (KO) mice and grown in the presence of murine M-CSF. During cultivation, BM cells expressed increasing levels of macrophage-specific receptor F4/80. Within 6 to 9 days, almost 100% of BM cells expressed high levels of F4/80 (supplemental Table 2), indicating that these cells became fully mature macrophages. M0 macrophages were polarized into M1 or M2 phenotypes by incubation with LPS/IFNγ or murine IL-4, respectively (Figure 7A). Fluorescence-activated cell sorter analysis demonstrated MMR expression in both M0 and M1 macrophages, but only M2 polarization induced high levels of this marker on the cell surface (supplemental Table 3). In both WT and Mmp9-KO macrophages, flow cytometry indicated similar levels of F4/80 expression across all macrophage phenotypes, whereas gene expression analysis confirmed proper expression of the genes known to be associated with the M1 phenotype (Nos2, Tnf)46 and the M2 phenotype (Arg1, Mrc1, and Ym1)1,47 (supplemental Figure 5). In addition, western blot analysis of cell lysates confirmed the reciprocal expression of iNOS and α-arginase-1 in M1 and M2 macrophages (supplemental Figure 6).

Figure 7.

Angiogenic potential of murine BM-derived M2-macrophages depends on their TIMP-1-free proMMP-9. (A) Polarization of murine BM-derived macrophages. M0 macrophages were generated from WT mice (upper) or Mmp9-KO mice (lower) by incubation of BM cells in the presence of murine M-CSF. Following a 7-day maturation, M0 macrophages were incubated for 24 hours either in the mixture of IFNγ and LPS to induce the M1 phenotype or with IL-4 to induce the M2 phenotype. Phase contrast images were acquired using an Olympus CKX-41 microscope equipped with Olympus U-LS30-3 video camera and Infinity Capture software and processed using Adobe Photoshop. Objective lens, ×20. (B) Western blot analysis of MMP-9 and TIMP-1 produced by mature and polarized murine macrophages. Following maturation and polarization, murine macrophages were switched to SF medium. CM was collected 48 hours later and analyzed for production of MMP-9 and TIMP-1. Control proteins, murine recombinant proMMP-9 (105 kDa) and TIMP-1 (28 kDa), were loaded in the wells of the same gel to provide the means of quantification. After SDS-PAGE and transfer, the membrane was cut horizontally, and the upper potion was probed with anti-murine MMP-9 antibody, whereas the lower potion was probed with anti–TIMP-1 antibody. The position of molecular weight markers is indicated on the left. (C) Angiogenic capacity of murine M2 macrophages depends on expression of MMP-9. Intact M2 macrophages generated from BM of WT or Mmp9-KO mice were incorporated into 3D collagen onplants and analyzed in the CAM angiogenesis assay. SF medium was used as a negative no-cell (NC) control. The data are from 2 independent experiments, each involving from 4 to 6 embryos, each bearing from 5 to 6 onplants. Bar graph presents means ± SEM of fold changes in the levels of angiogenesis compared with NC control (1.0). *P < .05 and **P < .01 in comparison with angiogenesis levels induced by WT M2 macrophages. (D) Angiogenic capacity of murine M2 macrophages is sensitive to TIMP-1. M2 macrophages generated from BM of WT or Mmp9-KO mice were incubated in SF medium for 48 hours. CM was incorporated into 3D collagen onplants alone or with 4 ng of recombinant murine TIMP-1 per onplant. SF medium was used as a negative control. Data are from 2 independent CAM experiments, each involving from 4 to 6 embryos per variant (5-6 onplants per embryo). Bar graph presents means ± SEM of fold changes in the levels of angiogenesis compared with SF control (1.0). *P < .05, **P < .01, and ***P < .0001, all in comparison with angiogenesis levels induced by WT M2 macrophages.

Following these confirmatory characterizations, we analyzed the expression levels of proMMP-9 and TIMP-1 in different types of murine macrophages. Western blot analysis documented the lack of MMP-9 production by any of Mmp9-KO macrophages and indicated that WT macrophages produced similar levels of proMMP-9 regardless of their phenotypic identity (Figure 7B, upper). Importantly, M2 polarization resulted in almost complete loss of TIMP-1 secretion, independent of Mmp9 genetic status of murine macrophages (Figure 7B, lower).

We then compared the in vivo angiogenic potential of WT and Mmp9-KO M2 macrophages. Providing a proof of principle, the angiogenic potential of M2 macrophages depended on their Mmp9 status. Thus, the genetic lack of MMP-9 was associated with a 2.4-fold decrease in angiogenic potency of Mmp9-KO M2 macrophages compared with WT counterparts (Figure 7C). A similar 2.7-fold differential in angiogenic potency was also observed between CM from WT and Mmp9-KO M2 macrophages (Figure 7D). Importantly, the high angiogenic potential of CM from WT M2 macrophages was sensitive to addition of exogenous murine TIMP-1, further indicating that the enzymatic activity of MMP-9 was required and responsible for the bulk of angiogenic induction (Figure 7D). Demonstrating the lack of nonspecific negative effects, the low levels of angiogenesis induced by Mmp9-KO M2 macrophages were not affected by exogenous TIMP-1.

Discussion

The initial angiogenic switch often requires the influx of mature neutrophils that release their secretory cargo containing highly angiogenic proMMP-9.24,28 Being naturally free of any complexed TIMP-1,33,48 neutrophil proMMP-9 is rapidly activated into a potent proteolytic enzyme releasing direct angiogenic factors, such as vascular endothelial growth factor and FGF-2, sequestered in the extracellular matrix.31,34 The initial neutrophil influx24 is followed by infiltration by peripheral blood monocytes and BM-derived myeloid cells, which differentiate into various subpopulations of tissue macrophages, including the M1 and M2 macrophages.4,8 The putative role of TAMs as myeloid cells that deliver proangiogenic proMMP-9 has been widely reported,16,17,36,37,49 but secretion of distinctively angiogenic proMMP-9 has not been linked specifically to tumor-promoting M2 macrophages. Therefore, the aim of this study was to determine the precise phenotype of human monocyte–derived macrophages that is capable of inducing high levels of angiogenesis in a proMMP-9–dependent manner. We compared the angiogenesis-inducing capacities of macrophage cell precursors (monocytes), their differentiated progenies (mature M0 macrophages), and their polarized descendants (M1 and M2 macrophages) and extended our findings to murine BM-derived macrophages.

In the in vivo angiogenesis assays used in this study, neovascularization critically depends on initial supplementation of proMMP-9 or its delivery by the influxing inflammatory cells into onplants in chick embryos and angiotubes in mice.25,28,34 Therefore, these live animal models were specifically chosen to quantify the angiogenic capacities of the monocytic cells in relation to their produced proMMP-9, a molecule that has long been closely linked to the induction of angiogenesis.50 We demonstrated that human M2 macrophages indeed represent the monocytic cell type that is most capable of inducing levels of angiogenesis comparable with those induced by highly angiogenic neutrophils, whereas M0 mature macrophages and M1-polarized macrophages are much less angiogenic. Importantly, the MMP-9 affinity depletion of cell CM indicated that the major angiogenesis-inducing capacity of all tested macrophages was contained in their secreted proMMP-9. Furthermore, the inhibitory effects of the unique function-blocking mAb 7-11C indicated that similar to neutrophil proMMP-9, the MMP-9 zymogen produced by M2 macrophages requires activation to exert its angiogenesis-inducing potency in live animals.

In agreement with the dependency of our in vivo angiogenesis assays on proMMP-9, peripheral blood monocytes secreting little if any proMMP-9 exhibited almost no angiogenic capacity. The mature and polarized macrophages, producing elevated amounts of proMMP-9 over monocytes, exhibited substantially different levels of angiogenesis even though their proMMP-9 was supplied in equal amounts by intact cells, within the CM or as purified zymogen. Natural TIMP-1 complexing represented an alternative scenario to substantiate the low angiogenic potential of proMMP-9 produced by M0 and M1 macrophages. Several biochemical studies have demonstrated that encumbrance of proMMP-9 by TIMP-1 negatively affects zymogen activation and diminishes the proteolytic activity of activated enzyme.31-34 By using live animal models, we showed that TIMP-1 complexing to neutrophil proMMP-9 would ultimately abrogate induction of physiologic and pathologic angiogenesis.28,31,34 Herein, quantitative analysis of proMMP-9 purified from distinct monocytic cell types confirmed that the highly angiogenic M2 macrophages had the lowest levels of TIMP-1 complexed with their proMMP-9. In contrast, near stoichiometric levels of TIMP-1 are naturally complexed with proMMP-9 that is secreted by low-angiogenic M0 and M1 macrophages, which on siRNA-mediated downregulation of TIMP-1 become angiogenic, consistent with the dependency of angiogenesis on TIMP-free status of proMMP-9. Reciprocally, IL-4–induced downregulation of TIMP1 expression in low-angiogenic M0 macrophages renders the resulting M2-polarized macrophages with angiogenic capacity, which can now be attributed to the TIMP-1–deficient status of their secreted proMMP-9. Due to substantial decrease in TIMP-1 production on M2 polarization, ≥90% of the proMMP-9 molecules secreted by M2 macrophages are not complexed with TIMP-1, making M2 proMMP-9 readily activatable in the tissue microenvironment.

In the context of a pathologic microenvironment, IL-4 produced by T lymphocytes has been shown to enhance protumor functions of TAMs.49 In the present study, IL-4–induced shutdown of TIMP-1 expression in M2-polarized macrophages appears to be cell lineage–specific since it does not occur in other hematopoietic cell types represented by leukemia cells, HL-60 promyeloblasts and U937 histiocytes or in human cancer cells such as HT-1080 fibrosarcoma. This unexpected finding cautions against straightforward extrapolations of observations on immortalized leukemia cell lines directly to natural leukocytes and their role in angiogenesis. Therefore, it is important that herein, innate monocyte-derived macrophages were used for IL-4–induced polarization.

To validate our findings generated with human cells, we used murine BM-derived macrophages and demonstrated that their IL-4–induced M2 polarization also resulted in a dramatic down-regulation of TIMP-1 and production of angiogenic TIMP-free proMMP-9. Therefore, our newly established biochemical mechanisms underlying specific induction of angiogenesis by human macrophages could be extended to other mammalian species. Furthermore, by comparing M2 macrophages from WT and Mmp9-KO mice, we not only directly linked murine M2 macrophages with production of a distinct angiogenesis-inducing MMP-9 but also demonstrated that the overall production of proMMP-9 is required since Mmp9-null M2 macrophages exhibited low angiogenic potential regardless that TIMP-1 was downregulated. Together with our previous studies on human and murine neutrophils,28,31,34 the findings of the present study provide proof of concept that the mechanisms underlying in vivo angiogenesis critically depend on proMMP-9 supplied by specific subpopulations of BM-derived cells.

In conclusion, we demonstrated an essential requirement for specific inflammatory leukocytes from 2 different species to produce TIMP-1–free or TIMP-1–deficient proMMP-9 to induce high levels of angiogenesis. For therapeutic purposes, it might be important to explore whether the M2→M1 switch, induced for example by IFNγ treatment of TAMs,51 would be accompanied by an induction of TIMP-1 expression and production of nonangiogenic, TIMP-1–encumbered proMMP-9. The current investigations in our laboratory would allow us also to answer whether TIMP-1 downregulation occurs in the actual tissue microenvironment during M2 polarization and whether alternatively activated M2 macrophages, eg, M2-skewed TAMs in solid tumors, secrete TIMP-1–deficient and highly angiogenic proMMP-9. If so, the specific cytokine-induced down-regulation of TIMP-1 gene expression and production of TIMP-free MMP-9 will now constitute an additional marker of the M2 subpopulation of TAMs responsible for fueling the formation of angiogenic blood vessels, the major conduits of tumor cell dissemination and metastasis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr R. Fridman for human recombinant TIMP-1 and MMP-9 and Dr C. Overall for murine recombinant TIMP-1 and MMP-9.

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health, National Cancer Institute grants R01CA157792 and R01CA105412 and Scripps Translational Science Institute grant UL1 TR000109-05 Pilot 2.2.284R1 (to J.P.Q. and E.I.D.), a research supplement to R01CA105412 from the National Institutes of Health Program to Promote Diversity in Health-Related Research (to E.Z.), and fellowships from the Max Kade Foundation (to B.S.), the Lundbeck and Willum Kann Rasmussen Foundations (to A.J.-J.), and the Swiss National Science Foundation for Prospective Researches (to P.M.).

This is manuscript no. 24036 from TSRI.

Footnotes

The online version of this article contains a data supplement.

The publication costs of this article were defrayed in part by page charge payment. Therefore, and solely to indicate this fact, this article is hereby marked “advertisement” in accordance with 18 USC section 1734.

Authorship

Contribution: E.Z. performed most of the incorporated experiments, analyzed the data, and contributed to the writing of the paper; B.S. initially observed a diminishment of TIMP-1 protein on M2 macrophage polarization and conducted critical initial experiments; T.A.K. performed morphological analyses of isolated cells and cultured macrophages; A.J.-J. performed macrophage gene expression analysis; P.M. performed some gene expression and western blot analyses; J.P.Q. initiated and designed the project, interpreted results, and wrote the manuscript; and E.I.D. also initiated and designed the project, provided essential expertise on live animal models, interpreted the results, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: The authors declare no competing financial interests.

The current affiliation for B.S. is Department of Dermatology, Medical University of Vienna, Vienna, Austria.

Correspondence: Elena I. Deryugina, Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Rd, SP3030-3120, La Jolla, CA 92037; e-mail: deryugin@scripps.edu; and James P. Quigley, Department of Cell and Molecular Biology, The Scripps Research Institute, 10550 North Torrey Pines Rd, SP3030-3120, La Jolla, CA 92037; e-mail: jquigley@scripps.edu.

References

- 1.Van Dyken SJ, Locksley RM. Interleukin-4- and interleukin-13-mediated alternatively activated macrophages: roles in homeostasis and disease. Annu Rev Immunol. 2013;31:317-343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2.Galdiero MR, Garlanda C, Jaillon S, Marone G, Mantovani A. Tumor associated macrophages and neutrophils in tumor progression. J Cell Physiol. 2013;228(7):1404–1412. doi: 10.1002/jcp.24260. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Grivennikov SI, Greten FR, Karin M. Immunity, inflammation, and cancer. Cell. 2010;140(6):883–899. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.01.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Qian BZ, Pollard JW. Macrophage diversity enhances tumor progression and metastasis. Cell. 2010;141(1):39–51. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.03.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.De Palma M, Lewis CE. Macrophage regulation of tumor responses to anticancer therapies. Cancer Cell. 2013;23(3):277–286. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2013.02.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Senovilla L, Vacchelli E, Galon J, et al. Trial watch: Prognostic and predictive value of the immune infiltrate in cancer. OncoImmunology. 2012;1(8):1323–1343. doi: 10.4161/onci.22009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Quatromoni JG, Eruslanov E. Tumor-associated macrophages: function, phenotype, and link to prognosis in human lung cancer. Am J Transl Res. 2012;4(4):376–389. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Biswas SK, Mantovani A. Macrophage plasticity and interaction with lymphocyte subsets: cancer as a paradigm. Nat Immunol. 2010;11(10):889–896. doi: 10.1038/ni.1937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sica A, Porta C, Riboldi E, Locati M. Convergent pathways of macrophage polarization: The role of B cells. Eur J Immunol. 2010;40(8):2131–2133. doi: 10.1002/eji.201040736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3(1):23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Stout RD, Watkins SK, Suttles J. Functional plasticity of macrophages: in situ reprogramming of tumor-associated macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2009;86(5):1105–1109. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0209073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mantovani A, Sica A. Macrophages, innate immunity and cancer: balance, tolerance, and diversity. Curr Opin Immunol. 2010;22(2):231–237. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2010.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Coffelt SB, Lewis CE, Naldini L, Brown JM, Ferrara N, De Palma M. Elusive identities and overlapping phenotypes of proangiogenic myeloid cells in tumors. Am J Pathol. 2010;176(4):1564–1576. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2010.090786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hanahan D, Folkman J. Patterns and emerging mechanisms of the angiogenic switch during tumorigenesis. Cell. 1996;86(3):353–364. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80108-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Bergers G, Benjamin LE. Tumorigenesis and the angiogenic switch. Nat Rev Cancer. 2003;3(6):401–410. doi: 10.1038/nrc1093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bergers G, Brekken R, McMahon G, et al. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 triggers the angiogenic switch during carcinogenesis. Nat Cell Biol. 2000;2(10):737–744. doi: 10.1038/35036374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Giraudo E, Inoue M, Hanahan D. An amino-bisphosphonate targets MMP-9-expressing macrophages and angiogenesis to impair cervical carcinogenesis. J Clin Invest. 2004;114(5):623–633. doi: 10.1172/JCI22087. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Huang S, Van Arsdall M, Tedjarati S, et al. Contributions of stromal metalloproteinase-9 to angiogenesis and growth of human ovarian carcinoma in mice. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94(15):1134–1142. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.15.1134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Coussens LM, Raymond WW, Bergers G, et al. Inflammatory mast cells up-regulate angiogenesis during squamous epithelial carcinogenesis. Genes Dev. 1999;13(11):1382–1397. doi: 10.1101/gad.13.11.1382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chantrain CF, Shimada H, Jodele S, et al. Stromal matrix metalloproteinase-9 regulates the vascular architecture in neuroblastoma by promoting pericyte recruitment. Cancer Res. 2004;64(5):1675–1686. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.can-03-0160. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Jodele S, Chantrain CF, Blavier L, et al. The contribution of bone marrow-derived cells to the tumor vasculature in neuroblastoma is matrix metalloproteinase-9 dependent. Cancer Res. 2005;65(8):3200–3208. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-04-3770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Masson V, de la Ballina LR, Munaut C, et al. Contribution of host MMP-2 and MMP-9 to promote tumor vascularization and invasion of malignant keratinocytes. FASEB J. 2005;19(2):234–236. doi: 10.1096/fj.04-2140fje. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Martin MD, Carter KJ, Jean-Philippe SR, et al. Effect of ablation or inhibition of stromal matrix metalloproteinase-9 on lung metastasis in a breast cancer model is dependent on genetic background. Cancer Res. 2008;68(15):6251–6259. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-0537. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nozawa H, Chiu C, Hanahan D. Infiltrating neutrophils mediate the initial angiogenic switch in a mouse model of multistage carcinogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2006;103(33):12493–12498. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0601807103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zijlstra A, Seandel M, Kupriyanova TA, et al. Proangiogenic role of neutrophil-like inflammatory heterophils during neovascularization induced by growth factors and human tumor cells. Blood. 2006;107(1):317–327. doi: 10.1182/blood-2005-04-1458. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shojaei F, Singh M, Thompson JD, Ferrara N. Role of Bv8 in neutrophil-dependent angiogenesis in a transgenic model of cancer progression. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105(7):2640–2645. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0712185105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pahler JC, Tazzyman S, Erez N, et al. Plasticity in tumor-promoting inflammation: impairment of macrophage recruitment evokes a compensatory neutrophil response. Neoplasia. 2008;10(4):329–340. doi: 10.1593/neo.07871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Bekes EM, Schweighofer B, Kupriyanova TA, et al. Tumor-recruited neutrophils and neutrophil TIMP-free MMP-9 regulate coordinately the levels of tumor angiogenesis and efficiency of malignant cell intravasation. Am J Pathol. 2011;179(3):1455–1470. doi: 10.1016/j.ajpath.2011.05.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuang DM, Zhao Q, Wu Y, et al. Peritumoral neutrophils link inflammatory response to disease progression by fostering angiogenesis in hepatocellular carcinoma. J Hepatol. 2011;54(5):948–955. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2010.08.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Bausch D, Pausch T, Krauss T, et al. Neutrophil granulocyte derived MMP-9 is a VEGF independent functional component of the angiogenic switch in pancreatic ductal adenocarcinoma. Angiogenesis. 2011;14(3):235–243. doi: 10.1007/s10456-011-9207-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ardi VC, Kupriyanova TA, Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Human neutrophils uniquely release TIMP-free MMP-9 to provide a potent catalytic stimulator of angiogenesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104(51):20262–20267. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0706438104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ogata Y, Itoh Y, Nagase H. Steps involved in activation of the pro-matrix metalloproteinase 9 (progelatinase B)-tissue inhibitor of metalloproteinases-1 complex by 4-aminophenylmercuric acetate and proteinases. J Biol Chem. 1995;270(31):18506–18511. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.31.18506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Opdenakker G, Van den Steen PE, Dubois B, et al. Gelatinase B functions as regulator and effector in leukocyte biology. J Leukoc Biol. 2001;69(6):851–859. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ardi VC, Van den Steen PE, Opdenakker G, Schweighofer B, Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Neutrophil MMP-9 proenzyme, unencumbered by TIMP-1, undergoes efficient activation in vivo and catalytically induces angiogenesis via a basic fibroblast growth factor (FGF-2)/FGFR-2 pathway. J Biol Chem. 2009;284(38):25854–25866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.033472. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.De Palma M, Venneri MA, Galli R, et al. Tie2 identifies a hematopoietic lineage of proangiogenic monocytes required for tumor vessel formation and a mesenchymal population of pericyte progenitors. Cancer Cell. 2005;8(3):211–226. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.08.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ahn GO, Brown JM. Matrix metalloproteinase-9 is required for tumor vasculogenesis but not for angiogenesis: role of bone marrow-derived myelomonocytic cells. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(3):193–205. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2007.11.032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Du R, Lu KV, Petritsch C, et al. HIF1alpha induces the recruitment of bone marrow-derived vascular modulatory cells to regulate tumor angiogenesis and invasion. Cancer Cell. 2008;13(3):206–220. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.01.034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Welford AF, Biziato D, Coffelt SB, et al. TIE2-expressing macrophages limit the therapeutic efficacy of the vascular-disrupting agent combretastatin A4 phosphate in mice. J Clin Invest. 2011;121(5):1969–1973. doi: 10.1172/JCI44562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Coffelt SB, Tal AO, Scholz A, et al. Angiopoietin-2 regulates gene expression in TIE2-expressing monocytes and augments their inherent proangiogenic functions. Cancer Res. 2010;70(13):5270–5280. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-0012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Movahedi K, Laoui D, Gysemans C, et al. Different tumor microenvironments contain functionally distinct subsets of macrophages derived from Ly6C(high) monocytes. Cancer Res. 2010;70(14):5728–5739. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-4672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Deryugina EI, Ratnikov BI, Bourdon MA, Gilmore GL, Shadduck RK, Müller-Sieburg CE. Identification of a growth factor for primary murine stroma as macrophage colony-stimulating factor. Blood. 1995;86(7):2568–2578. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Conn EM, Botkjaer KA, Kupriyanova TA, Andreasen PA, Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Comparative analysis of metastasis variants derived from human prostate carcinoma cells: roles in intravasation of VEGF-mediated angiogenesis and uPA-mediated invasion. Am J Pathol. 2009;175(4):1638–1652. doi: 10.2353/ajpath.2009.090384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jablonska J, Leschner S, Westphal K, Lienenklaus S, Weiss S. Neutrophils responsive to endogenous IFN-beta regulate tumor angiogenesis and growth in a mouse tumor model. J Clin Invest. 2010;120(4):1151–1164. doi: 10.1172/JCI37223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Chick embryo chorioallantoic membrane models to quantify angiogenesis induced by inflammatory and tumor cells or purified effector molecules. Methods Enzymol. 2008;444:21-41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Deng B, Wehling-Henricks M, Villalta SA, Wang Y, Tidball JG. IL-10 triggers changes in macrophage phenotype that promote muscle growth and regeneration. J Immunol. 2012;189(7):3669–3680. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1103180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Qin H, Holdbrooks AT, Liu Y, Reynolds SL, Yanagisawa LL, Benveniste EN. SOCS3 deficiency promotes M1 macrophage polarization and inflammation. J Immunol. 2012;189(7):3439–3448. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1201168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Raes G, De Baetselier P, Noël W, Beschin A, Brombacher F, Hassanzadeh Gh G. Differential expression of FIZZ1 and Ym1 in alternatively versus classically activated macrophages. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;71(4):597–602. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Van den Steen PE, Dubois B, Nelissen I, Rudd PM, Dwek RA, Opdenakker G. Biochemistry and molecular biology of gelatinase B or matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9). Crit Rev Biochem Mol Biol. 2002;37(6):375–536. doi: 10.1080/10409230290771546. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.DeNardo DG, Barreto JB, Andreu P, et al. CD4(+) T cells regulate pulmonary metastasis of mammary carcinomas by enhancing protumor properties of macrophages. Cancer Cell. 2009;16(2):91–102. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Deryugina EI, Quigley JP. Pleiotropic roles of matrix metalloproteinases in tumor angiogenesis: contrasting, overlapping and compensatory functions. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803(1):103–120. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2009.09.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Duluc D, Delneste Y, Tan F, et al. Tumor-associated leukemia inhibitory factor and IL-6 skew monocyte differentiation into tumor-associated macrophage-like cells. Blood. 2007;110(13):4319–4330. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-02-072587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.