Abstract

Objective

To assess the effect of a pilot intervention to promote clinician-patient communication about physical activity on patient ratings of their perceived competence for physical activity and their clinicians’ autonomy-supportiveness.

Methods

Family medicine clinicians (n=13) at two urban community health centers were randomized to early or delayed (8 months later) communication training groups. The goal of the training was to teach the 5As (Ask, Advise, Agree, Assist, Arrange) for physical activity counseling. Outcome measures were changes in patient perceptions of autonomy support (modified Health Care Climate Questionnaire, mHCCQ) and perceived competence (Perceived Competence Scale for physical activity, PCS) completed via surveys at baseline, post-intervention and six-month follow-up.

Results

Patients (n=326) were mostly female (70%) and low income. Using a generalized estimating equations model (GEE) with patients nested within clinician, patient perceived autonomy support increased at post-intervention compared to baseline (mean HCCQ scores 3.68 to 4.06, p=0.03). There was no significant change in patient perceived competence for physical activity.

Conclusions

A clinician-directed intervention increased patient perceptions of clinician autonomy support but not patient perceived competence for physical activity.

Practice Implications

Clinicians working with underserved populations can be taught to improve their autonomy supportiveness, according to patient assessments of their clinicians.

1. Introduction

With high rates of overweight, obesity, and related chronic conditions in the US and globally,(1;2) there is an urgent need to translate effective, evidence-based physical activity interventions into primary care and community settings.(3) A recent meta-analysis showed that counseling provided by primary care clinicians has small to medium effect sizes on patient reported physical activity at 12 months.(6) The 5A guidelines, in which clinicians Ask about (or Assess), Advise about, Agree upon, Assist with and Arrange follow-up regarding patients’ behavior change efforts(7;8) are recommended as an evidence-based practice for health behavior counseling. The present study linked the 5As to constructs from self-determination theory (SDT) in its design and measurement. SDT is a theory of human motivation, with the foundation that individuals have needs for perceived autonomy, competence (e.g., feeling able to achieve a desired outcome), and relatedness to others.(9)

The objective of this paper is to evaluate a 5As clinician intervention to promote physical activity counseling on 1) patient perception of clinician autonomy support, and 2) patient perceived competence for physical activity. We hypothesized that the intervention would increase (1) patient perceptions of their clinician’s autonomy supportiveness and (2) patient perceived competence for physical activity.

2. Methods

A full description of the study design and protocol is reported elsewhere.(11)

2.1. Design

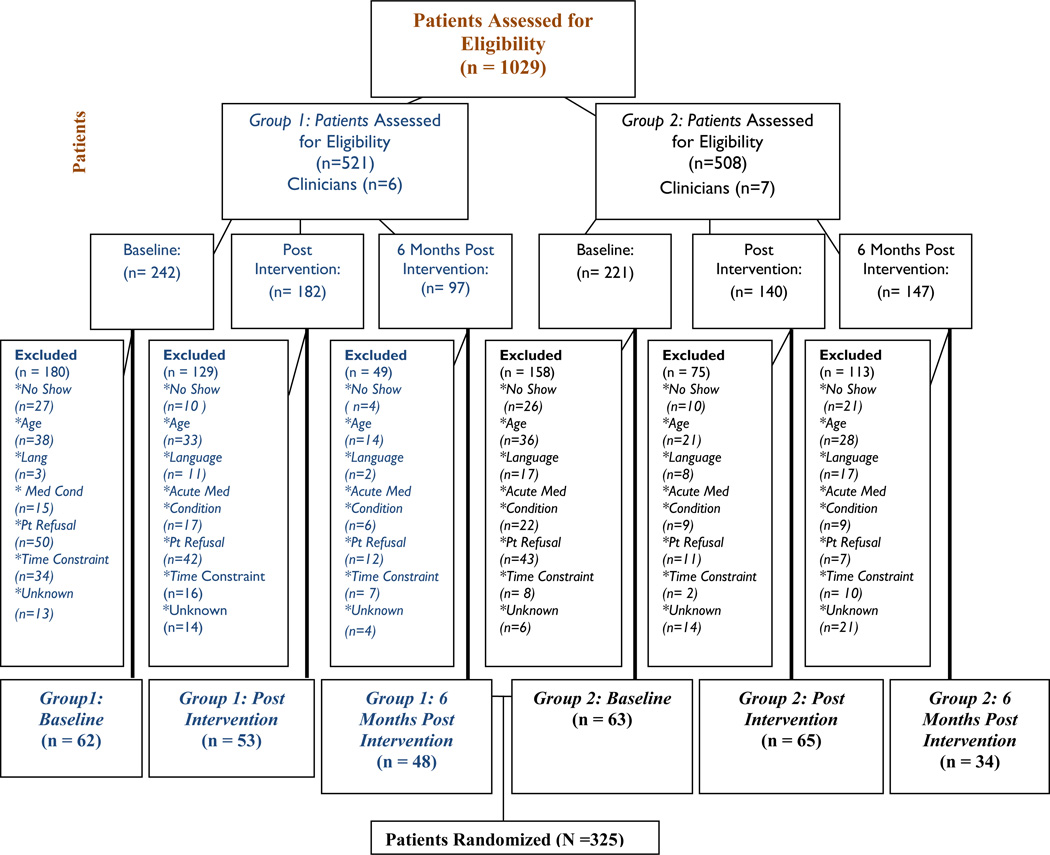

The study used a two-group pragmatic pilot RCT design with clinicians (n=13) as the unit of intervention and patients (n=325) as the unit of analysis. Group 1 clinicians (n=6) participated in the training intervention first and Group 2 (n=7) received the intervention eight months later. The University of Rochester Research Subjects Review Board approved the study protocol. The intervention period was from June 2009-October 2011. Figure 1 shows participant flow in the design, with exclusions or refusals.

Figure 1. Participant flow through study (CONSORT Diagram).

*note the patients are not mutually inclusive across groups nor intervention points. The n for each time point are independent from each other.

2.2 Setting

The setting consisted of two large practices serving a predominantly low-income, ethnically diverse population of 14,000 patients in Rochester, New York.

2.3 Recruitment, Enrollment

Clinicians were recruited, enrolled, and randomized prior to patient recruitment. Clinicians were recruited via a presentation by the principal investigator at a staff meeting. Clinician and patient eligibility criteria are shown in Table 1. Patients were eligible if they were scheduled for routine chronic care or health maintenance follow-up visits for which physical activity counseling would likely be appropriate.

Table 1.

Clinician and Patient Eligibility Criteria

| Inclusion Criteria | Exclusion Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

|

Patient Participants |

|

|

|

Clinician Participants |

|

|

2.4 Randomization

Randomization was at the level of the clinician. After providing informed consent and completing a baseline assessment, each clinician was randomized to Group 1 or Group 2 by a statistician using computerized random number generation. The study statistician was responsible for sequence generation, allocation concealment, and implementation. Two sample t-tests for continuous variables and chi-square tests for categorical variables were used to evaluate the success of the randomization; there was no significant differences in baseline measures between the two groups and no adjustments were needed.

2.5 Clinician baseline assessment

Prior to receiving the training intervention, each clinician completed a baseline survey. The survey asked about demographic information, attitudes about physical activity counseling, barriers to counseling, and knowledge of community resources for exercise.

2.6 Patient recruitment and enrollment

On data collection days, a research assistant briefly met with the clinician prior to the start of their session to review the schedule and identify potentially eligible patients. When eligible patients entered the examination room for their medical visit, a nurse assistant mentioned the study. If the patient expressed interest, a research assistant entered the room to provide additional details about the study. If the patient agreed to participate, the research assistant obtained written informed consent.

2.7 Patient assessments

Patients completed a 15-minute post-visit patient survey administered by the research assistant to patients at baseline, immediately post intervention, and follow-up (6-month) time points. Patients completed the surveys at the end of their visit. Each patient contributed one assessment during the study period. Survey questions are described further in the Measures section.

2.8 Clinician follow-up assessment

At the end of the study, clinicians completed a survey and an individual interview. The survey included the same baseline questions attitudes asking and also satisfaction with the intervention. The individual interviews asked about the most meaningful lessons learned, and perspectives on feasibility and sustainability of the intervention.

2.9 Description of intervention (Table 2)

The intervention consisted of four one-hour training sessions at the clinic site. Sessions 1–3 were conducted as a group; Session 4 was individually-based. Each session was facilitated by the principal investigator. Clinicians were trained using didactic materials, skills/competency checklists, role play, and cognitive rehearsal.(12–14) The purpose of the intervention was to increase use of the 5As and enhance patient autonomy support and perceived competence for physical activity.

Table 2.

Outline of clinician training (Intervention) sessions

| Session | Content outline |

|---|---|

| 1 | -Evidence-based recommendations for physical

activity -Definitions of the 5As -Eliciting motivation using autonomy support skills such as acknowledging a person’s feelings or perspectives about physical activity -Introduction to basic problem-solving techniques for common barriers to physical activity. |

| 2 | -Review of the 5As -Emphasizing strategies to provide support and encourage patients to set goals, if willing. -Techniques to ascertain patient’s perceived competence to change -Provide list of local free or low cost community resources for exercise |

| 3 | -Practice the 5As including referral to an

appropriate community resource, while working with a standardized

patient actor (SP) and observed by a peer. -Explore patients’ willingness to participate in a community exercise program. -Reinforce eliciting patients’ perceived competence to change and exploring potential barriers to change -Promote active decision-making and goal-setting for health with their patients for physical activity |

| 4 | -SP meets with each clinician individually to

perform an assessment of skills according to a predefined checklist of

competencies -SP portrays a challenging patient with multiple medical and psychosocial conditions and barriers to exercise |

2.10 Measures (Table 3)

The survey included two measures that are the focus of this paper: patient perceptions of clinician autonomy support and patient perceived competence for physical activity.

Table 3.

modified Health Care Climate Questionnaire (mHCCQ) and Perceived Competence Scale (PCS) with corresponding items.

| Measure | Items |

|---|---|

| modified Health Care Climate Questionnaire (mHCCQ) | -I feel that my health care providers provide

me with choices and options about exercising regularly -I feel that my health care providers provide me with choices and options about exercising regularly (including not exercising regularly) -I feel my health care providers understand my views about exercising regularly -I feel my health care providers show confidence in me that I can exercise regularly (that I can improve my exercise habits) -My health care practitioner(s) listen(s) to how I would like to do things regarding my exercise -My health care providers try to understand how I see my exercising before suggesting any changes |

| Perceived Competence Scale (PCS) | -I feel confident in my ability to exercise

regularly -I feel capable of exercising regularly now -I am able to meet the challenge of exercising regularly |

To measure patient perceptions of clinician autonomy support, we used the modified Health Care Climate Questionnaire (mHCCQ).(9) The mHCCQ is a reliable, validated measure (9) (alpha=0.96) which asks participants to rate their responses to six statements on a five-point Likert scale. A higher mHCCQ score represents a greater degree of autonomy support reported by patients towards their clinicians.

We used the Perceived Competence Scale (PCS) to measure patient perceived competence in their ability to increase their physical activity.(15) The PCS is a reliable (alpha=0.80), (9) validated measure of a person’s feelings of competence for physical activity. It has four statements with a five-point Likert scale. A higher PCS score represents a higher degree of patient perceived competence for physical activity.

2.11 Statistical analysis

All analyses are based on a significance level of 0.05. All primary and secondary outcomes were analyzed using generalized estimating equations models with patients nested within clinician. We used an identity link and unstructured correlation matrix to account for the nesting. The models were unadjusted, using no control variables or statistical corrections.

3. Results

Participant flow through the study is shown in Figure 1. Of the 15 eligible clinicians, 13 agreed to participate; one declined to relocation and one due to illness. The mean age of patient participants was 43 years, with the majority of participants, female (70%) and African American or Hispanic (75% and 15% respectively). The majority (70%) had an annual income of less than US$20,000.

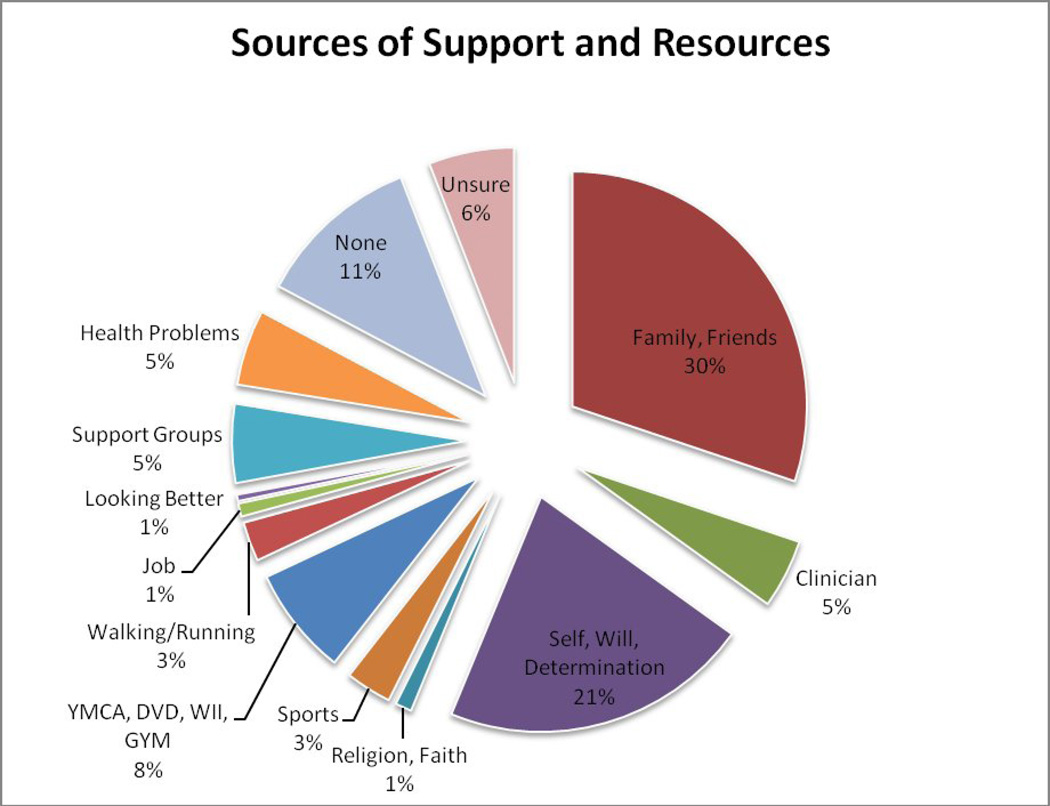

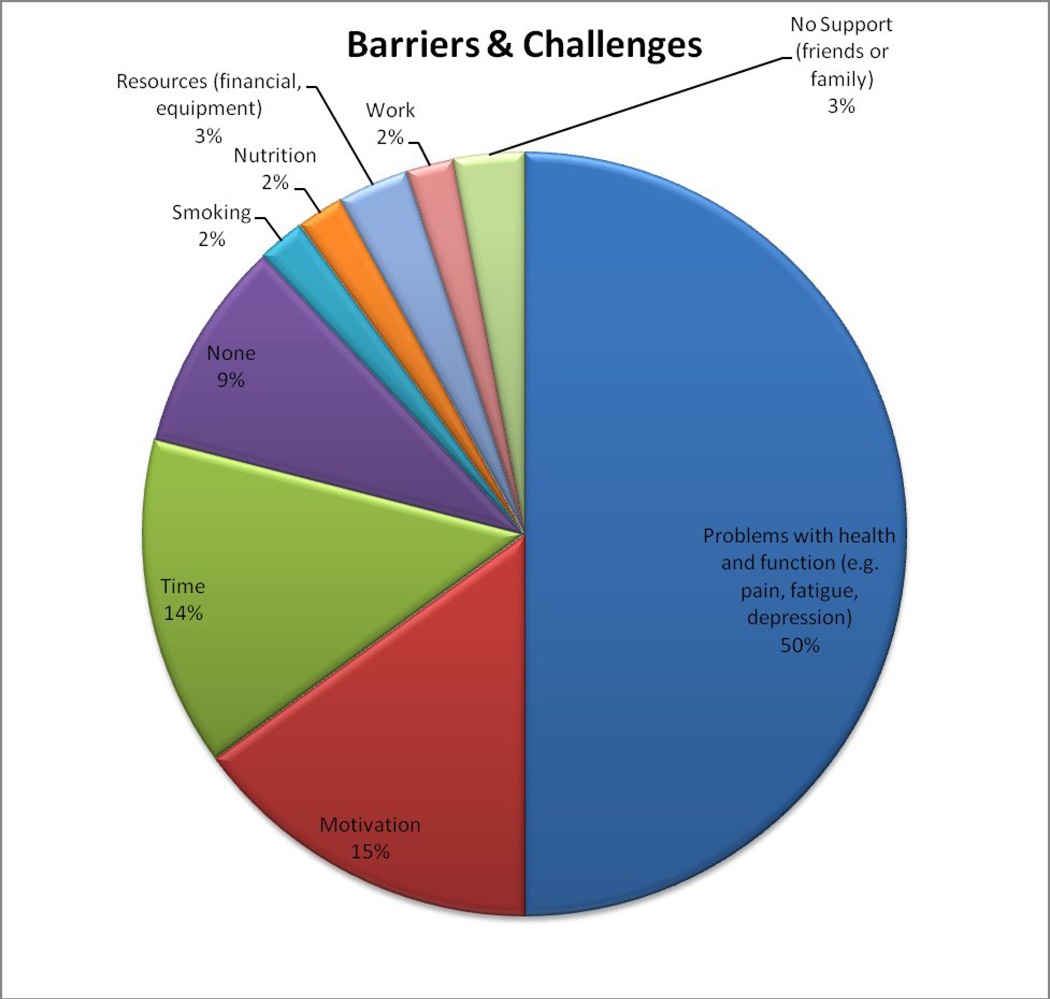

Figures 2 and 3 show participants’ responses to the single open-ended survey questions about their barriers, resources, and support for physical activity. Half (50%) of patient participants reported health-related limitations such as respiratory problems, chronic pain, fatigue, and/or difficulty walking or standing as their most significant barrier to physical activity. The most frequent sources of support were family, friends, and/or social groups (35%), and having determination or “will” within oneself (21%).

Figure 2. Participants’ sources of support and resources for physical activity* (n=326).

*Responses are to a single open-ended question, “What sources of support, resources, or inner qualities do you have that can help you improve your physical activity?”

Figure 3. Participants’ barriers and challenges to physical activity* (n=326).

*Responses are to a single open-ended question, “What do you find most difficult or challenging to improving your physical activity/exercise habits?”

For the clinician participants, the majority were female (75%) with an average work experience of 15 years. Each clinician completed all training sessions and study assessments. The most commonly mentioned barriers to counseling reported by clinicians were time constraints, competing demands/heavy workload, and lack of knowledge about how to bill or code for counseling.

3.1 Effect of intervention on patient reports of clinician autonomy supportiveness for physical activity

Autonomy support increased significantly at post-intervention compared to baseline (mean mHCCQ scores from baseline to post-intervention, 3.68 to 3.94, p=0.03), representing a small effect size. There was no significant difference between post-intervention (mean mHCCQ score=3.94) and 6-month mHCCQ score (mean mHCCQ score=4.06), though the 6 month mHCCQ score remained elevated compared to baseline.

3.2 Effect of intervention on patient perceived competence for physical activity

There was no significant change in patients’ perceived competence for physical activity at any of the time points (mean PCS scores from baseline to post-intervention, 3.75 to 3.88, p=0.54). Those with fewer comorbidities (< 2, mean PCS 3.97) had higher baseline PCS scores than those with more comorbidities (3+, mean PCS 3.64) (p=0.002). However, there was no significant difference in PCS over time between the two comorbidity groups.

3.3 Clinician-reported changes in their frequency

Clinicians reported that they significantly increased their frequency of counseling of assessing a patient’s exercise history (p=0.02) a knowledge of local resources that could meet their patients’ needs (p=0.03); and counseling in a cost effective way. In the post-study individual interviews, clinicians reported that the availability and familiarity with the option to refer to the community exercise program was a major asset and motivator for their counseling about physical activity.

4. Discussion & Conclusion

4.1 Discussion

This study found that a pilot clinician intervention increased patient perception autonomy supportiveness, but not perceived competence for physical activity. Autonomy supportiveness encompasses communication skills such as acknowledging a patient’s feelings or perspective, providing a menu of options or choices, minimizing control or pressure, and encouraging active decision-making and goal-setting for health. The intervention reiterated these concepts and attempted to apply them in realistic ways. Therefore, clinicians may have felt more competent about their ability to counsel and familiarized with a choice of skills they could use to work with their patients. Other randomized interventions have shown that when autonomy support increases, patients are more likely to stop smoking,(21) increase physical activity and lose weight, (19;22) and engage in preventive dental care.(23)

Perceived competence is potentially more distal to the intervention than autonomy supportiveness since autonomy support reflects patients’ perception of clinician behavior rather than their ability to be physically active. Participants were from an underserved population with several barriers to physical activity; thus, their perceived competence for physical activity may have been more difficult to change. The intervention did not address in-depth how to tailor counseling for physical activity in patients with complex co-morbidities. Thus, clinicians may have felt less competent adapting the counseling to challenging clinical situations.

4.1.1 Limitations

This study sample had a small number of clinicians; therefore findings are warrant replication. By design, this study cannot comment on individual patients’ changes in measures over time, but rather aggregates of patient reports clustered by clinician. This study was not designed to evaluate the effect of the training intervention on patients’ actual physical activity; however, patient outcomes will be the subject of future work.

4.2 Conclusion

A theoretically-based, clinician-directed intervention increased underserved patients’ reports of clinician autonomy supportiveness but not patient perceived competence for physical activity. Future work is needed to examine the relationship between clinician autonomy supportiveness and patient physical activity.

4.3 Practice Implications

In the US, the Patient Centered Medical Home (PCMH) initiative has created a resurgence of interest in helping primary care patients change health behaviors.(4) The PCMH standards include key elements to “support self-care”, e.g. counseling for least 50% of patients to adopt healthy behaviors.(5) This intervention represents one strategy to offer training and tools to help clinicians translate evidence based guidelines into practice.

“The authors confirm all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/persons(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story.”

Acknowledgements

Support: National Cancer Institute (K07CA126985), and ARRA Administrative Supplement K07CA126985-02S1 (PI Carroll), Clinicaltrials.gov identifier NCT01419093

Role of the funding source

The authors must submit a statement regarding the role of the funding source

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest: The authors report no conflicts of interest and have no financial interests in the content of this manuscript.

Reference List

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999–2008. JAMA. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization. Global health risks: Mortality and burden of disease attributable to selected major risks. 2011 http://www.who.int/healthinfo/global_burden_disease/GlobalHealthRisks_report_full.pdf.

- 3.Estabrooks PA, Glasgow RE. Translating effective clinic-based physical activity interventions into practice. American Journal of Preventive Medicine. 2006;(4:Suppl) Suppl-56 doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2006.06.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Rosenberg CN, Peele P, Keyser D, McAnallen S, Holder D. Results from a patient-centered medical home pilot at UPMC Health Plan hold lessons for broader adoption of the model. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;(11):2423–2431. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.National Committee for Quality Assurance. Patient-centered medical home (PCMH) 2011 standards. 2011 http://www.iafp.com/pcmh/ncqa2011.pdf.

- 6.Orrow G, Kinmonth AL, Sanderson S, Sutton S. Effectiveness of physical activity promotion based in primary care: systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. BMJ. 2012;344:e1389. doi: 10.1136/bmj.e1389. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitlock EP, Orleans CT, Pender N, Allan J. Evaluating primary care behavioral counseling interventions: an evidence-based approach. Am J Prev Med. 2002;22(4):267–284. doi: 10.1016/s0749-3797(02)00415-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Glynn TJ, Manley MW. How to help your patients stop smoking: A manual for physicians. NIH Publication 89-3064 ed. Bethesda, MD: National Cancer Institute; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williams GC, Grow VM, Freedman ZR, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight-loss maintenance. Journal of Personality & Social Psychology. 1996;70(1):115–126. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ng J, Ntoumanis N, Thogersen-Ntoumanis C, Deci E, Ryan RM, Duda JL, et al. Self-determination theory applied to health contexts: a meta-analysis. Perspectives on Psychological Science. 2012;7:325–340. doi: 10.1177/1745691612447309. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carroll JK, Fiscella K, Epstein RM, Sanders MR, Williams GC. A 5As communication intervention to promote physical activity in underserved populations. BMC Health Services Research. 2012;12:374. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-12-374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lewin SA, Skea ZC, Entwistle V, Zworenstein M, Dick J. Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centered approach in clinical consultations. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2001:4. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Epstein RM, Franks P, Fiscella K, Shields CG, Meldrum SC, Kravitz RL, et al. Measuring patient-centered communication in patient-physician consultations: theoretical and practical issues. Soc Sci Med. 2005 Oct;61(7):1516–1528. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2005.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Epstein RM. Assessment in medical education. N Engl J Med. 2007;356:387–396. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra054784. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Williams GC, Grow VM, Freedman ZR, Ryan RM, Deci EL. Motivational predictors of weight loss and weight maintenance. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(1):115–126. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.1.115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Williams GC, Deci EL. Internalization of biopsychosocial values by medical students: a test of self-determination theory. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1996;70(4):767–779. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.70.4.767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox ME, Yancy WS, Jr, Coffman CJ, Ostbye T, Tulsky JA, Alexander SC, et al. Effects of counseling techniques on patients' weight-related attitudes and behaviors in a primary care clinic. Patient Educ Couns. 2011;85(3):363–368. doi: 10.1016/j.pec.2011.01.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubak S, Sandbaek A, Lauritzen T, Borch-Johnsen K, Christensen B. General practitioners trained in motivational interviewing can positively affect the attitude to behaviour change in people with type 2 diabetes. One year follow-up of an RCT, ADDITION Denmark. Scand J Prim Health Care. 2009;27(3):172–179. doi: 10.1080/02813430903072876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fortier MS, Sweet SN, Tracy L, O'Sullivan, Williams GC. A self-determination process model of physical activity adoption in the context of a randomized controlled trial. Psychology of Sport and Exercise. 2007;(8):741–757. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fortier MS, Hogg W, O'Sullivan TL, Blanchard C, Reid RD, Sigal RJ, et al. The physical activity counselling (PAC) randomized controlled trial: rationale, methods, and interventions. Appl Physiol Nutr Metab. 2007;32(6):1170–1185. doi: 10.1139/H07-075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Williams GC, McGregor H, Sharp D, Kouides RW, Levesque CS, Ryan RM, et al. A Self-Determination Multiple Risk Intervention Trial to Improve Smokers' Health. J Gen Intern Med. 2006 doi: 10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.00621.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Silva MN, Vieira PN, Coutinho SR, Minderico CS, Matos MG, Sardinha LB, et al. Using self-determination theory to promote physical activity and weight control: a randomized controlled trial in women. J Behav Med. 2010;33(2):110–122. doi: 10.1007/s10865-009-9239-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Halvari AE, Halvari H. Motivational predictors of change in oral health: an experimental test of self-determination theory. Motivation and Emotion. 2006;30:295–306. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Silva MN, Markland D, Minderico CS, Vieira PN, Castro MM, Coutinho SR, et al. A randomized controlled trial to evaluate self-determination theory for exercise adherence and weight control: rationale and intervention description. BMC Public Health. 2008;8:234. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-8-234. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]