Highlights

► This is the second report of pregnancy following endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS). ► The role of adnexectomy is controversial in stage I ESS. ► Adnexectomy does not appear to affect survival in stage I ESS.

Keywords: Pregnancy, Endometrial stromal sarcoma, Conservative surgery

Introduction

Endometrial stromal tumors are extremely rare and account for fewer than 0.2% of all malignant uterine tumors. Mitotic rates do not separate endometrial stromal sarcoma (ESS) into low (≤ 10 high power fields) and high (> 10 high power fields) grade as in the past. In fact, infiltrating tumors composed of cells resembling the proliferative phase of the endometrium should be classified as ESS regardless of the number of mitoses. Conversely, undifferentiated ESS (UESS) is the former “high-grade sarcoma.”

The natural course of ESS is characterized by slow clinical progression, local recurrences (in the pelvis, ovaries, and intestinal wall) and occasional metastases, whereas UESS is extremely aggressive and survival is limited.

Case description

The patient was a nulligravida 32-year-old woman. At age 28 years the patient was diagnosed with a small myoma of approximately 3 cm that had gradually grown to 80 × 61 mm with worsening of hypermenorrhea (Fig. 1). At age 32 years she underwent laparotomy for myomectomy; the histologic diagnosis was ESS with 8 mitoses per 10 highly magnified fields and infiltrated radial or circumferential margin (Figs. 2 and 3). The immunohistochemical study showed findings consistent with endometrial stromal tumor: positive for vimentin, CD 10, smooth-muscle actin, and estrogen and progesterone receptors. The cell proliferation index (Ki-67) was less than 10%.

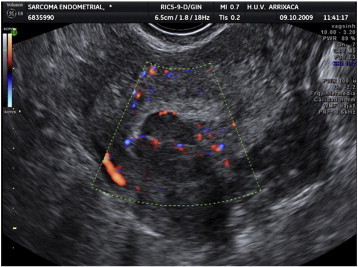

Fig. 1.

Transvaginal ultrasound. Note the uterus with presumed leiomyoma. Also note the myoma vascularization on Doppler.

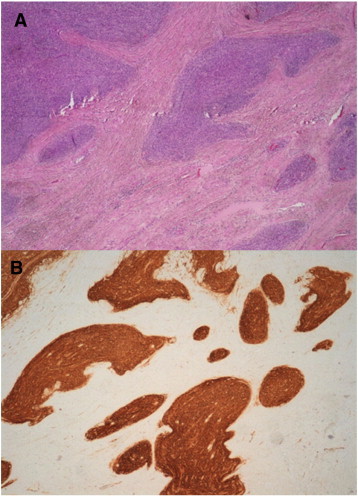

Fig. 2.

(composition). A, irregular nests and tumor irregularities that permeate the myometrium (original magnification × 4). B, strong staining in tumor cells with CD-10 immunohistochemical staining.

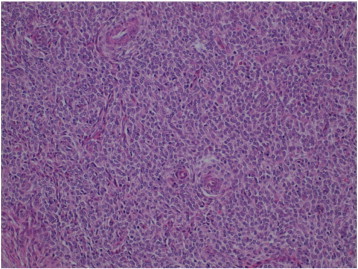

Fig. 3.

Detailed view of tumor cells composed of a uniform proliferation of oval or spindle-shaped cells, oval nuclei and scant cytoplasms, that swirl around small vessels. No atypias or increase in mitotic rates are observed (original magnification × 20).

In view of the diagnosis, repeat laparotomy and total hysterectomy or increased margins were suggested to the patient. However, the patient declined any type of surgery before attempting pregnancy, as she wished to have offspring and, therefore, underwent a complete study with tumor markers, repeat endometrium biopsy, magnetic resonance imaging, and positron-emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT), all with negative results. Progestin treatment with megestrol acetate 80 mg/d was initiated, and the dose was subsequently doubled 1 month after treatment was started.

Sixteen months after the surgery, the patient decided to consult a fertility clinic to assess a possible pregnancy. The couple was immediately included in an in vitro fertilization program. The oocytes were vitrified so that the procedure could be carried out once the endometrium was physiologically prepared. Following a failed fresh embryo transfer cycle, two cryopreserved embryos were transferred and a twin dichorionic-diamniotic pregnancy resulted. The course was normal except for threat of preterm delivery. Spontaneous membrane rupture occurred prematurely at 32 weeks. The patient was informed of the option to undergo c-section and hysterectomy during the same surgery, but declined because the twins were premature (32 weeks) and their course was unknown (weight 1700 g and 1710 g; Apgar scores of 9/10 for both). The uterine cavity was found to be normal during the laparotomy; however, a 3-cm myometrium-dependent formation of hard consistency was observed in the left horn and on top of the previous scar was observed. The placenta was sent for further study to the anatomic pathology department, with no unusual characteristics. The patient was informed of the surgical findings during the c-section, but preferred to postpone the hysterectomy until the infants had progressed adequately. Breast-feeding was initiated, but the patient had spontaneous menstruation from the second month despite lactation. Based on the 2-month postpartum follow-up consisting of cytology, ultrasound, laboratory workup, and hysteroscopy plus repeat endometrial biopsy, the patient was diagnosed with proliferative endometrium. Six months postpartum, the ultrasound revealed a uterus of 7.8 × 6.4 cm with a cavity distorted by a hypodense nodule originating from the myometrium of 34 × 26 mm. Another nodule of 31 × 26 mm was observed next to the first, on the posterior aspect of the uterus. Because recurrent or persistent disease was suspected and the infants had progressed adequately, the patient underwent hysterectomy without adnexectomy; wedges were also taken from both ovaries as well as from a small adhesion in the fundus of the uterus and intraoperatively found to be benign on histology. The definitive anatomical pathology diagnosis was ESS, International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics (FIGO) stage IB (IC in the FIGO 1988 classification), with immunohistochemistry positive for CD 10 and for estrogen and progesterone receptors. The cell proliferation index was very low (Ki 67 < 1%). The biopsy referred to as adhesion to serosal layer of the uterus was diagnosed as two neoplastic islets with a diameter of 0.10 and 0.25 mm. Therefore, the confirmation of recurrent or persistent disease was found after hysterectomy.

At the postoperative follow-up visit, the patient was asymptomatic and the pelvic ultrasound and PET-CT scans were negative. Three cycles of GnRh analogs were prescribed, followed by megestrol acetate 160 mg/d. The laboratory workup showed follicle-stimulating hormone 5 IU/L, luteinizing hormone 13 IU/L, and estradiol 38 pg/mL. Tumor markers were negative. Five years after the diagnosis, the patient remained asymptomatic and all follow-up was normal, except for a slight elevation in CA-125 to 64 IU/mL which has persisted at the levels of previous follow-up tests. All imaging tests (ultrasound, CT, PET-CT scans) have remained negative.

Discussion

The immunohistochemical phenotype of ESS includes typical positive reactions for vimentin and CD10, and other markers (keratins, smooth-muscle and muscle-specific actin, estrogen and progesterone receptors) are often expressed. Of these, CD10 and smooth-muscle actin are the most useful for diagnosis of ESS.

It is important to complete conservative surgery in young patients once fertility is achieved, even if recurrent or persistent disease is not suspected, as the risk of recurrence is high. In ESS, most authors propose hysterectomy with double adnexectomy (Bohr and Thomsen, 1991) followed by medroxyprogesterone acetate (71% estrogen- and 95% progesterone-receptor expression) with a response rate of 46% and disease stabilization of 46%.

Some authors (Shah et al., 2008) report that bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy does not affect survival or recurrence time in cases of stage I ESS (evidence level II-2) and, therefore, propose ovary-sparing treatment in premenopausal women even though the tumor is hormone-sensitive. Another paper (Stadsvold et al., 2005) reports a case of ESS in a 16-year-old woman who underwent uterus- and ovary-sparing treatment. However, the role of adnexectomy is controversial. Other authors (Berchuck et al., 1990; Park et al., 2008) reported that the highest recurrence rate in stage I was observed in patients with ovaries and, therefore, most authors perform salpingo-oophorectomy in these patients.

There are no clinical guidelines for young patients who desire to preserve fertility, and we found only two cases of gestation after UESS (Yan et al., 2010) or ESS (Delaney et al., 2012 Aug). In these cases, conservative surgery is possible. This surgery is later completed with another operation to increase the margins (Yan et al., 2010) and wait for spontaneous pregnancy (Yan et al., 2010; Delaney et al., 2012 Aug) or proceed with in vitro fertilization as in our patient (this was done for the purpose of achieving pregnancy as soon as possible and to complete the surgery afterwards).

The usefulness of lymphadenectomy is still unknown, although some authors report a higher incidence of lymph node involvement (10%) than previously expected, which suggests that lymphadenectomy may play a role. This has not been confirmed by other authors (Shah et al., 2008).

Progesterone is used because it counteracts the proliferative effect induced by estrogens. It has been reported that the lack of intratumoral estrogen-sulfotransferase enzyme could allow estrogen levels to encourage tumor growth and favor its progression. This is also the case of aromatase inhibitors (letrozole) (Reich and Regauer, 2007) because intratumoral aromatase expression has been observed in 80% of these tumors and GnRH analogs are also used. The impact of hormonal therapy is not well defined in the early stages of the disease (Reich and Regauer, 2007) and there is also no evidence for treatment duration. It has been suggested that the treatment should last 5 years (and be life-long for others) because the recurrence rate is 50% at 36 to 68 months or even years later and is not affected by adjuvant chemotherapy or radiation therapy. We treated our patient with megestrol acetate 160 mg/d and without chemotherapy, whereas the authors of (Yan et al., 2010) use 20 mg/d and adjunctive chemotherapy (etoposide and cisplatin). Because the tumor is hormone-dependent, hormone replacement therapy and tamoxifen are contraindicated in premenopausal patients.

Radiation therapy does not improve stage I prognosis and, therefore, would only be necessary in UESS or when deep myometrial invasion is present (Weitmann et al., 2002).

The prognosis of ESS confined to the uterus (stage I) is relatively good, and 5-year survival is 80% to 100%. The prognosis is less favorable in women with advanced stages, who have a 5-year survival rate of 40% to 50%. The most important prognostic factors are staging, and for some authors, extrauterine growth is more closely related to recurrence and prognosis than mitotic activity or DNA content. Even in stage I, the rate of pelvic recurrence is 25% to 50%. Lastly, for (Stadsvold et al., 2005) salpingo-oophorectomy, adjuvant radiation therapy, lymphadenectomy, and the presence of affected lymph nodes were not significant risk factors.

In conclusion, we found few literature cases (13) of pregnancy after leiomyosarcoma diagnosis (Salman et al., 2007), and only one case of pregnancy after UESS (Yan et al., 2010). Our case is the second to be described in cases of ESS after the case reported in (Delaney et al., 2012 Aug).

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest.

Contributor Information

M.L. Sánchez-Ferrer, Email: marisasanchezf@yahoo.es.

F. Machado-Linde, Email: fmachadol@hotmail.com.

B. Ferri-Ñíguez, Email: belenferri@msn.es.

M. Sánchez-Ferrer, Email: marinasanchezf@yahoo.es.

J.J. Parrilla-Paricio, Email: jjparri@um.es.

References

- Berchuck A., Rubin S.C., Hoskins W.J., Saigo P.E., Pierce V.K., Lewis J.L., Jr. Treatment of endometrial stromal tumors. Gynecol. Oncol. 1990;36:60–65. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohr L., Thomsen C.F. Low-grade stromal sarcoma: a benign appearing malignant uterine tumour; a review of current literature. Differential diagnostic problems illustrated by four cases. Eur. J. Obstet. Gynecol. Reprod. Biol. 1991;39:63–69. doi: 10.1016/0028-2243(91)90144-a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Delaney A.A., Gubbels A.L., Remmenga S., Tomich P., Molpus K. Successful pregnancy after fertility-sparing local resection and uterine reconstruction for low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012 Aug;120:486–489. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31825a7397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park J.Y., Kim D.Y., Suh D.S., Kim J.H., Kim Y.M., Kim Y.T., Nam J.H. Prognostic factors and treatment outcomes of patients with uterine sarcoma: analysis of 127 patients at a single institution, 1989–2007. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2008;134:1277–1287. doi: 10.1007/s00432-008-0422-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich O., Regauer S. Hormonal therapy of endometrial stromal sarcoma. Curr. Opin. Oncol. 2007;19:347–352. doi: 10.1097/CCO.0b013e3281a7ef3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salman M.C., Guler O.T., Kucukali T., Karaman N., Ayhan A. Fertility-saving surgery for low-grade uterine leiomyosarcoma with subsequent pregnancy. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2007;98:160–161. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2007.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shah J.P., Bryant C.S., Kumar S., Ali-Fehmi R., Malone J.M., Jr., Morris R.T. Lymphadenectomy and ovarian preservation in low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Obstet. Gynecol. 2008;112:1102–1108. doi: 10.1097/AOG.0b013e31818aa89a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadsvold J.L., Molpus K.L., Baker J.J., Michael K., Remmenga S.W. Conservative management of a myxoid endometrial stromal sarcoma in a 16-year-old nulliparous woman. Gynecol. Oncol. 2005;99:243–245. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2005.06.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weitmann H.D., Kucera H., Knocke T.H., Pötter R. Surgery and adjuvant radiation therapy of endometrial stromal sarcoma. Wien. Klin. Wochenschr. 2002;114:44–49. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan L., Tian Y., Fu Y., Zhao X. Successful pregnancy after fertility-preserving surgery for endometrial stromal sarcoma. Fertil. Steril. 2010;93 doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2009.09.024. (269e13) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]