Abstract

The virus validation of three steps of Biotest Pharmaceuticals IGIV production process is described here. The steps validated are precipitation and removal of fraction III of the cold ethanol fractionation process, solvent/detergent treatment and 35 nm virus filtration. Virus validation was performed considering combined worst case conditions. By these validated steps sufficient virus inactivation/removal is achieved, resulting in a virus safe product.

Keywords: Intravenous immunoglobulin, Cold ethanol fractionation, Virus filtration, Solvent/detergent, Low pH, Virus inactivation

Highlights

► Virus validation for a new immunoglobulin preparation for intravenous use. ► A combination of three different and robust virus inactivation/removal procedures is incorporated in the production process. ► Effective inactivation or removal of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses is demonstrated. ► The tested procedures have the potential to remove a broad range of emerging pathogens.

1. Introduction

One of the most important clinical applications of intravenous immunoglobulin (IGIV) is to supply antibodies to patients who are antibody deficient. Patients with inherited (primary) antibody deficiencies are treated throughout their lives with relatively high doses of IGIV. Patients who develop secondary antibody deficiencies because of disease or disease therapy may also receive high dose IGIV for long periods of time. Since regular exposure to human plasma protein therapy carries the risk of infection with blood-borne pathogens, increasing the pathogen safety of IGIV, without diminishing its clinical efficacy, is essential and required by regulatory authorities for marketing authorization. Validation of virus inactivation and removal should be performed in compliance with current guidelines [1,2].

All plasma used for the production of Biotest IGIV1 is obtained from licensed plasmapheresis centers. Plasma donations are made by qualified, selected donors and all donations are carefully screened serologically and minipools by nucleic acid amplification technique (NAT) for HIV, Hepatitis A virus (HAV), Hepatitis B virus (HBV), Hepatitis C virus (HCV) and Parvovirus B19. As all screening is limited by the sensitivity of the screening assays and the viruses screened for, virus removal and inactivation during the production of Biotest IGIV significantly contribute to the virus safety of the product. The steps of virus inactivation and removal of Biotest IGIV and their efficacy are described here.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Scale down

The studies were performed in compliance with current guidelines [1,2] in a scaled-down version of the production process using the same parameters and controls that are used in large-scale manufacturing. Scale-down reduction factors were based on the equipment used for virus validation studies and considered the volumes of reaction containers, the size of filter disks with a defined filtration area, the size of 35 nm filter cartridges and the available volume of test materials. The scale down factor for each process step was defined by comparing the production scale to virus validation scale. Scale-down runs were performed for each production step prior to virus validation studies, controlling the process parameters such as pH, temperature, protein concentration, concentration of alcohol, tri-n-butyl phosphate (TNBP) or Triton X-100 to demonstrate comparability to production scale.

2.2. Manufacturing description

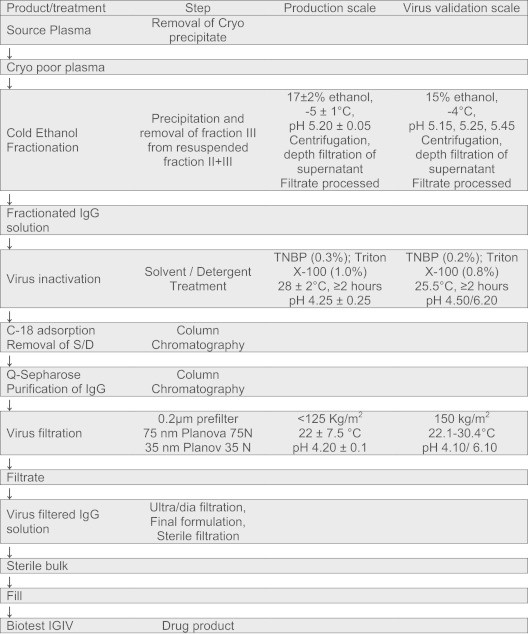

The manufacturing process is illustrated in Fig. 1 and is described as follows: the plasma is tempered at 2–8 °C for up to 16 h and the cryoprecipitate is removed by centrifugation. Cold ethanol fractionation of the cryo poor plasma is performed, including the most effective and crucial step of precipitation and removal of fraction III. From resuspended fraction II+III, fraction III is precipitated with 17% ethanol at −5 °C and removed by centrifugation. The centrifugate is clarified by depth filtration using filter aid, the pH is adjusted and the protein solution is ultrafiltered and sterile filtered.

Fig. 1.

Biotest IGIV production process and virus validation conditions.

The final IgG solution is subjected to virus inactivation using TNBP and Triton X-100 at pH 4.25 and 28 °C for a minimum of 2 h and solvent/detergent (S/D) is removed by C18 (Waters Corp.; Taunton, MA, USA) chromatography. For virus filtration, the IgG solution is prefiltered through a 0.2 μm filter, followed by a 75 nm filter and a 35 nm filter (Planova 75 N and 35 N; Asahi Kasei Bioprocess).

2.3. Process intermediates studied

Test materials for virus validation studies were produced in the Process Development Department at Biotest Pharmaceuticals Corporation, Boca Raton, Florida, USA, using a development scale manufacturing process that had been validated against the full scale manufacturing process of Biotest IGIV.

The following process steps were studied:

-

•

Precipitation and removal of fraction III and Depth Filtration.

-

•

Treatment with TNBP–Triton X-100 (S/D treatment).

-

•

Nanofiltration (35 nm virus filtration).

2.4. Equipment used in scale down studies

Scale-down studies and virus validation studies were performed using similar equipment. Test materials were transferred into specially designed, double-jacketed reaction containers, made from glass with a V-shaped bottom and connected to cooling or heating devices. Reaction containers were equipped with nozzles for adding test materials, reagents or for taking samples.

2.5. Viruses studied

Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV-1): HIV was used as a relevant virus for validation studies. The strain BRU was obtained from Georg Speyer House, Frankfurt, Germany. The virus (RNA, enveloped) was propagated and titrated on C8166 cells.

Pseudorabies Virus (PRV): PRV, an enveloped double-stranded DNA virus, was used to represent the herpesviruses and was obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC) (VR-135; strain Aujeszky). Human herpesviruses are not suitable for the studies due to interference by antibodies in human plasma. For virus titration BHK cells (CCL-10) were obtained from ATCC.

Bovine Viral Diarrhea Virus (BVDV): BVDV (pestivirus) was obtained from the ATCC (VR-534; strain NADL). For virus titration EBTr cells (ATCC; CCL-44) were used for virus titration. BVDV, an enveloped single-stranded RNA virus, is a model virus for Hepatitis C Virus.

Sindbis Virus (SinV): Sindbis Virus (ATCC: VR-1248) was obtained from Prof. Chr. Kempf, Central Laboratory of the Swiss Red Cross, Bern. For virus titration Vero cells (ATCC: CCL 81) were obtained from ATCC. Sindbis (an alphavirus) is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus that is also used as a model for Hepatitis C Virus.

West Nile Virus (WNV): WNV strain Uganda, obtained from ATCC (956), is an enveloped, single-stranded RNA virus. WNV is a relevant virus and its transmission by blood transfusion has been reported.

Porcine Parvovirus (PPV): PPV, a non-enveloped, small single-stranded DNA virus, was obtained from ATCC (VR-742; strain NADL-2) and was used as a model for Parvovirus B19. PPV is titrated on PK 13 cells (ATCC/CRL-6489) and does not cross react with antibodies to B19 Parvovirus. Parvoviruses are highly resistant to heat and to solvent/detergent treatment.

Murine Encephalomyelitis Virus (MEV): MEV was obtained from A. Scheidler (Robert-Koch-Institute) and is used as a model virus for Hepatitis A Virus. MEV is propagated and titrated on BHK cells (ATCC: CCL-10). MEV is a non-enveloped, small single-stranded RNA virus (Picorna virus) and is not neutralized by cross-reacting antibodies to Hepatitis A virus.

Bovine Parvovirus (BPV): BPV, a small, non-enveloped single-stranded DNA virus, was obtained from ATCC (VR-767; strain Haden) and is used as a model virus for parvovirus B19. It is propagated and titrated on KL-2 cells. BPV cross reacts with antibodies to B19 Parvovirus. This virus was used for virus filtration studies to test the potential influence of neutralizing antibodies on virus removal by virus filtration.

Simian Virus 40 (SV 40): SV40 was obtained from ATCC (SV40-PML 2, ATCC VR-821). It is highly resistant to chemical or physical treatment. For virus titration CV-1 cells from ATCC (CCL-70) were used. SV40, a double-stranded DNA virus, is used as a model for non-enveloped, highly resistant DNA viruses.

2.6. Virus titration and calculation of inactivation

Virus titers, prior to and after virus reduction or virus inactivation treatment, were determined by tissue culture infectious dose assays at 50% infectivity and calculated by the Spearman and Kaerber method [3]. Virus titers are expressed as the negative decadic logarithm. Virus clearance was calculated by comparing the virus titers prior to and after the virus removal or inactivation step.

2.7. Virus validation studies

Virus validation studies were conducted in the Pathogen Safety Department of Biotest, Dreieich, Germany. Virus validation studies addressed the worst case conditions (Fig. 1) assumed to be low concentrations of alcohol in precipitation studies, reduced S/D concentrations in inactivation studies and elevated temperatures or high volumes per filter area in filtration studies. Studies per step and virus were performed at least in duplicate to demonstrate the reproducibility of results.

2.7.1. Combination of fraction III precipitation and depth filtration of fraction III supernatant

Resuspended fraction II+III was spiked with test virus, fraction III was precipitated at assumed worst case conditions, using 15% ethanol at −4 °C. Tests were performed at pH 5.15, pH 5.25 and at pH 5.45. The precipitated fraction III was removed by centrifugation and the supernatant was filtered through a depth filter and was tested for virus removal. Same was done without depth filtration. Precipitation of fraction III, centrifugation, filtration and collection of filtrate was done at −4 °C.

2.7.2. Depth filtration of fraction III supernatant

Fraction III supernatant (17% ethanol) was spiked with test virus and filtered at −4 °C through a Cuno SP depth filter (Cuno, Meriden CT, USA) and tested under worst case conditions, i.e. elevated volume per filter area of ∼500 kg/m2 and pH 5.10, beyond the lower limit of production scale and at pH 5.45, beyond upper limit.

2.7.3. Solvent/detergent treatment

For S/D treatment, test material was spiked with test virus and treated at combined worst case conditions with a reduced concentration of 0.2% (w/w) TNBP and 0.8% (w/w) Triton X-100 and at a reduced temperature of 25.5 °C. The concentrations of S/D are at the lower end of the production range. To prevent potential inactivation of viruses by low pH during S/D treatment, runs were performed at neutral pH 6.20.

2.7.4. Virus filtration with a 35 nm Planova filter

Eluate from Q Sepharose (GE Healthcare Bio-Sciences; Uppsala, Sweden) was spiked with test virus and passed through a 75 nm prefilter followed by a 35 nm filter (Asahi Kasei Bioprocess; Brussels, Belgium) at worst case conditions, such as high temperature of ≤29.5 °C, high volume per filter area (150 kg/m2) and constant high pressure of ≥0.8 to ≤1.0 bar. Filtration was performed in dead end mode, where the feed is pumped directly against the filter membrane without any tangential flow.

3. Results

3.1. Precipitation and removal of fraction III

The conditions for validation of fraction III precipitation included lowering the ethanol concentration, shortening the precipitation time and increasing the temperature. The virus reductions observed at pH 5.10 are shown in Table 1 as a worst case condition.

Table 1.

Virus removal and inactivation during Biotest IGIV production.

| Virus reduction (log10) |

|||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enveloped viruses | Non-enveloped viruses | ||||||||

| Relevant virus | HIV | HBV | HCV |

WNV | B19 Parvovirus |

HAV | Resistant DNA viruses | ||

| Test virus | HIV | PRV | BVDV | Sindbis | WNV | PPV | BPV | MEV | SV40 |

| Fraction III precipitation and removala | 1.87 | 2.83 | <1.55 | 2.00 | |||||

| Fraction III precipitation and depth filtration combineda | 4.00 | 5.29 | |||||||

| Solvent–detergent treatmenta | >4.43 | >4.01 | >5.04 | >7.11 | >4.96b,a | ||||

| 35 nm Virus filtrationa | >5.19 | >4.64 | >4.88 | <1.0 | 6.18 | <1.0 | >5.02 | ||

| Low pH (as part of S/D or virus filtration) | 2.43 | 3.20 | <1.0 | 4.91 | 2.08 | <1.0 | <1.0 | ||

| Total clearance (log10)a | >9.62 | >8.65 | >11.79 | >7.11 | >4.96 | 10.18c | 5.29 | >7.02 | |

| Total clearance including low pH | >12.05 | >11.85 | >11.79 | >12.02 | >4.96 | 10.18c | 5.29 | >7.02 | |

Figures in bold are used for calculation of total clearance.

Even more effective reduction of WNV by >6.32 log10 was achieved when S/D treatment was combined with C-18 chromatography for removal of S/D.

Reduction of 10.18 log10 Parvo virus achieved by fraction III+depth filtration (PPV) and 35 nm virus filtration (BPV).

3.2. Depth filtration of fraction III supernatant

Validation of virus removal was tested at low pH of 5.10, reduced amount of filter aid and at a ratio of sample volume to filter area that was higher than the ratio used in manufacturing. Virus reductions were less than 1 log10 at every condition tested and none of the data were used to estimate total virus clearance.

3.3. Combination of fraction III precipitation and depth filtration of fraction III supernatant

Conditions for validating the combined steps of fraction III precipitation and depth filtration (Cuno) of the fraction III supernatant were essentially the same as those used for each step performed separately. Precipitation was performed at varied pH (pH 5.15, 5.25 and 5.45) to test pH values above and below the target pH for their effect in removing PPV and MEV. Of these variations, pH changes were the only parameters that had a significant effect on virus removal. The minimum virus removal values at pH 5.15 are reported in Table 1. Non-enveloped viruses, i.e. PPV and MEV are removed by ≥4.0 log10 at the worst case conditions tested. As shown in Table 2, pH can influence the efficacy of virus removal by this step.

Table 2.

Virus removal (log10) by precipitation and removal of fraction III at different pH, followed by depth filtration.

| Virus | pH 5.15 | pH 5.25 | pH 5.45 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PPV | 4.00 | 4.02 | >4.20 |

| MEV | 5.29 | 5.29 | >5.55 |

3.4. Solvent-detergent treatment

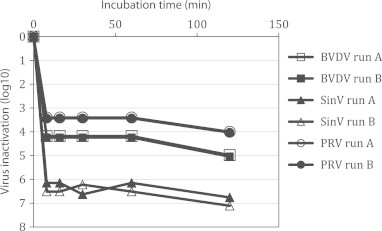

For S/D treatment, validation studies were performed using the lower limit of S/D concentration in IVIG manufacturing. The pH in validation studies was elevated to pH 6.20 to avoid any inactivation by low pH. The temperature was reduced to 25.5 °C, to below the minimum used in production. S/D inactivation was stopped by treating the test sample with C-18 Sepharose beads to remove the S/D reagents. Viruses were rapidly inactivated by S/D to below the limit of detection (Fig. 2). Inactivation of all test viruses was in the range of >4 to >7 log10 and the results are summarized in Table 1.

Fig. 2.

Inactivation of BVDV, SinV and PRV by TNBP/Triton X-100 at combined worst case conditions (0.2/0.8%, 25.5±0.5 °C and pH 6.20±0.05). BVDV run B was performed at pH 4.50. Inactivation below the limit of detection of all viruses was achieved after 8 min treatment. The demonstrated inactivation values depend on the titer of the stocks of the different test viruses.

3.5. 35 nm Virus filtration

Virus filtration studies were performed at high and low pH and with an excess of test sample with respect to filter surface area. Values at high pH were reported in Table 1. The data show that 35 nm filtration removed significant titers of all the enveloped viruses tested (HIV, PRV and BVDV) and also of non-enveloped viruses (BPV and SV40), depending on the size of the virus particles. Although BPV is small (18–24 nm), BPV virus particles are complexed with antibodies to Parvovirus B19 and their effective diameter is increased.

4. Discussion

4.1. Virus inactivation and removal

During plasma fractionation, classes of proteins are precipitated and separated from proteins in solution by centrifugation or filtration. Viruses are distributed into the fibrinogen precipitate (Cohn–Oncley fraction I) and the IgG fraction (Cohn–Oncley fractions II+III). The most effective virus removal step during cold ethanol fractionation to produce IgG is precipitation of fraction III [4]. This step was investigated at worst case conditions, i.e. reduced concentration of ethanol (15% instead of 17%), elevated temperature (−4 °C instead of −5 °C), reduced amount of filter aid and reduced filter area per volume.

The virus reduction data observed in this study showed that fraction III precipitation and removal by centrifugation when combined with the clarification by depth filtration in the presence of a filter aid was effective in removing two non-enveloped viruses that were used as models for B19 parvovirus and hepatitis A virus, i.e. PPV and MEV. Of these variations, pH changes were the only parameters that had an effect on virus removal. For each virus tested, the reduction in virus levels in the fraction III supernatant at pH 5.45 was greater than at pH 5.15. For the combination of precipitation of fraction III and depth filtration, less virus removal (PPV=4.00 log10; MEV=5.29 log10) was observed at the lowest pH tested and virus removal increased as the pH increased (Table 2). However, even at the lowest pH an effective removal of PPV by 4 log10 was demonstrated.

Solvent/detergent virus inactivation of enveloped viruses has been used to produce safe plasma products since 1985 when it was licensed in the manufacture of factor VIII, a product that carried a high risk of transmitting blood-borne viruses in the past, before specific virus inactivation steps were introduced. In 1985 and before, Horowitz and his group reported that the solvent/detergent process was an effective virus inactivation process for plasma derivatives, including IGIV [5–8]. Subsequently, virus inactivation by solvent/detergent was incorporated into other products [9–11]. S/D treatment in this study was performed at worst case conditions, i.e. reduced concentrations of TNBP and Triton X-100 (0.2% and 0.8% instead of 0.3% and 1.0%), reduced temperature of 25.5 °C (instead of 28 °C) and short incubation time of 2 h. In addition, the pH was increased to neutral range. Inactivation of enveloped viruses by S/D is fast and inactivation below the limit of detection is achieved after few minutes of treatment (Fig. 2). The S/D inactivation data reported in this study confirm the robust inactivation of enveloped viruses reported in the literature for IGIV and other plasma derivatives [12].

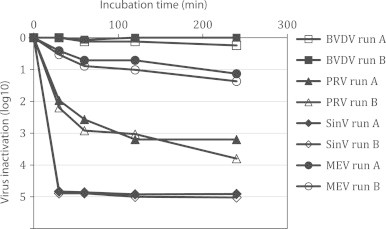

Low pH is not a designated virus inactivation step in the production process of Biotest IGIV. However, several steps in the production process are performed at low pH, e.g. S/D treatment. The potential influence of low pH on virus inactivation during S/D treatment was investigated. Testing was done using the same conditions as for S/D treatment but without the addition of S/D reagents. The protein concentration was elevated, the temperature was lowered to 25.5 °C and the pH was adjusted to the upper production limit of pH 4.5. As shown in Table 1, PRV and Sindbis virus were inactivated by 3.2 log10 and 4.91 log10, respectively (Fig. 3). Not inactivated at pH 4.50 were BVDV and MEV. Inactivation of the other test viruses (no kinetics tested) ranged from <1 to 2.43 log10.

Fig. 3.

Inactivation of BVDV, PRV SinV and MEV at pH 4.5±0.05 and 25±0.5 °C. Inactivation below the limit of detection was not achieved. Residual infectivity was detected in all samples. Bench controls at pH 6.20 for BVDV: 0.3 log10, for PRV: 1.14 log10, for SinV: 0.0 log10, for MEV: 0.43 log10.

Low pH inactivation was first observed by Reid et al. in 1988 [13], who reported that enveloped viruses such as Vaccinia, herpes simplex (HSV), mumps and Semliki Forest virus (SFV) were inactivated by pepsin treatment at pH 4. The data were confirmed by Kempf and others [14–16]. The data in this study confirm previous observations that incubation of IgG solutions at low pH inactivates some enveloped viruses but is less effective or even ineffective for non-enveloped viruses.

Virus filtration is a simple, robust, non-destructive process that adds size exclusion to conventional virus inactivation and partitioning procedures. The use of filtration with defined pore sizes in the nanometer range for removal of adventitious viruses is the first major advance in virus elimination since development of solvent-detergent procedures. As shown in Table 1, filtration performed in validation studies reported here removed all of the enveloped viruses studied (HIV, PRV and BVDV) but also a small non-enveloped virus, BPV. Although BPV is 18–24 nm in size, removal of viruses smaller than the nominal pore size of the nanofilter was due to antibody-complexed virus particles [17–19].

The results presented here demonstrate that the production process of Biotest IGIV employs three effective steps for inactivation and/or removal of enveloped and non-enveloped viruses. Virus reduction is caused by different mechanisms of action, thus viruses, which might escape one procedure, are inactivated or removed by one of the subsequent procedures. In addition to the three virus inactivating/removing steps, low pH, although not a dedicated inactivation step, can also contribute to virus inactivation of some sensitive viruses in a limited range.

Guidelines on virus validation for plasma derivatives [1,2] require a capacity of virus removal and inactivation, which can reliably remove a potential load of adventitious viruses. Virus inactivation or removal of enveloped viruses of at least 4.0 log10 by two steps and for non-enveloped viruses by one step of is considered as sufficient. The virus validation results for the IGIV presented here fulfills those requirements.

In conclusion, the robust virus removal and inactivation procedures used in Biotest Pharmaceuticals IGIV production remove the enveloped and non-enveloped blood-borne viruses that are known today and has the potential to remove a broad range of emerging pathogens that might contaminate future blood supplies. The three virus inactivation and/or removal procedures described here show high efficacy in inactivation and/or removal of test viruses and relevant viruses and in combination with selection of donors, careful screening serologically and by NAT, a virus safe final IGIV product results.

4.2. Prion removal

The production process of Biotest IGIV employs several steps, which are capable to remove prions. Those steps are cold ethanol fractionation, nanofiltration and column chromatography [20–22], as reported in abundance in the literature. However, product specific studies on the removal of prions were not performed, as Biotest IGIV is produced from US plasma only. In the US until today not a single native case of variant Creutzfeldt Jakob Disease (vCJD) was reported. Consequently, the probability of a plasma donation at risk for vCJD entering a plasma pool is extremely low. The risk R, calculated using the formula R=1−(1–p)n [23], is less than 1 donation at risk per 100,000 plasma pools for a prevalence p of <1 case of vCJD per 305,000,000 US residents and plasma pools of n=3000 donations. Therefore the risk of a vCJD donation in an US plasma pool can be considered as theoretical only. In case of such an unlikely event, the production steps have sufficient capacity to remove prions.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported in its entirety by Biotest AG, Dreieich, Germany and Biotest Pharmaceuticals, Boca Raton, FL, USA.

We also thank NewLab; Cologne, Germany for excellently performing the studies on HIV, WNV and BPV, and all technicans in the Pathogen Safety Lab at Biotest Dreieich. The technical support provided by John Hooper (BioCatalyst LLC, Liberty, Missouri, USA) is greatfully appreciated.

Footnotes

Biotest IGIV, manufactured by Biotest Pharmaceuticals; Boca Raton, FL, USA.

References

- 1.Guidelines on viral inactivation and removal procedures intended to assure the viral safety of human blood plasma products; WHO Technical Report series no. 924, 2004.

- 2.Guideline on Plasma Derived Medicinal Products; CPMP/BWP/269/95, rev. 3, 25 January 2001.

- 3.Cavalli-Sforza L. Gustav Fischer; Stuttgart: 1974. Biometrie Grundzuge Biologisch-medizinischer Statistik [Biometry, the basics of biological and medical statistics] [p. 171–3] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dichtelmüller H.O., Biesert L., Fabbrizzi F., Falbo A., Flechsig E., Gröner A. Contribution to safety of immunoglobulin and albumin from virus partitioning and inactivation by cold ethanol fractionation: a data collection from Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association member companies. Transfusion. 2011;51:1412–1430. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2010.03003.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Prince A.M., Horowitz B., Horowitz M.S., Zang E. The development of virus-free labile blood derivatives—a review. European Journal of Epidemiology. 1987;3:103–118. doi: 10.1007/BF00239746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Prince A.M., Horowitz B., Brotman B., Huima T., Richardson L., van den Ende M. Inactivation of Hepatitis B and Hutchinson strain non-A, non-B hepatitis viruses by exposure to Tween 80 and ether. Vox Sanguinis. 1984;46:36–43. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1984.tb00045.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Prince A.M., Horowitz B., Dichtelmüller H., Stephan W., Gallo R.C. Quantitative assays for evaluation of HTLV III inactivation procedures: tri(N-butyl) phosphate:sodium cholate and β-propiolactone. Cancer Research. 1985;45:4592s–4594ss. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Horowitz B., Wiebe M.E., Lippin A., Stryker M.H.G. Inactivation of viruses in labile blood products I. Disruption of lipid enveloped viruses by tri (n-butyl) phosphate detergent combinations. Transfusion. 1985;25:516–522. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1985.25686071422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Alonso W.R., Trukawinski S., Savage M., Tenold R.A., Hammond D.J. Viral inactivation of intramuscular immune serum globulins. Biologicals. 2000;28:5–15. doi: 10.1006/biol.1999.0234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Biesert L. Virus validation studies of immunoglobulin preparations. Clinical and Experimental Rheumatology. 1996;14(Suppl. 15):s47–s52. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rabenau H.F., Biesert L., Schmidt T., Bauer G., Cinatl J., Doerr H.W. SARS-corona virus (SARS-CoV) and the safety of a solvent/detergent treated immunoglobulin preparation. Biologicals. 2005;33:95–99. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2005.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dichtelmüller H.O., Biesert L., Fabbrizzi F., Gajardo R., Gröner A., von Hoegen I. Robustness of solvent/detergent treatment of plasma derivatives: a data collection from Plasma Protein Therapeutics Association member companies. Transfusion. 2009;49:1931–1943. doi: 10.1111/j.1537-2995.2009.02222.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Reid K.G., Cuthbertson B., Jones A.D.L., McIntosh R.V. Potential contribution of mild pepsintreatment at pH 4 to the viral safety of human immunoglobulin products. Vox Sanguinis. 1988;55:75–80. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.1988.tb05140.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Omar A., Kempf C., Immelmann A., Rentsch M., Morgenthaler J.J. Virus inactivation by pepsin treatment at pH 4 of IgG solutions: factors affecting the rate of virus inactivation. Transfusion. 1996;36:866–872. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1996.361097017171.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Louie R.E., Galloway C.J., Dumas M.L., Wong M.F., Mitra G. Inactivation of hepatitis C virus in low pH intravenous immunoglobulin. Biologicals. 1994;22:13–19. doi: 10.1006/biol.1994.1003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bos O.J.M., Sunye D.G.J., Nieuweboer C.E.F., van Engelenburg F.A.C., Schuitemaker H., Over J. Virus validation of pH 4-treated human immunoglobulin products produced by the Cohn Fractionation Process. Biologicals. 1998;26:267–276. doi: 10.1006/biol.1998.0148. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Troccoli N.M., McIver J., Losikoff A., Poiley J. Removal of viruses from human intravenous immune globulin by 35 nm nanofiltration. Biologicals. 1998;26:321–329. doi: 10.1006/biol.1998.0164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Caballero S., Nieto S., Gajardo R., Jorquera J.I. Viral safety characteristics of Flebogamma® DIF, a new pasteurized, solvent-detergent treated and Planova 20 nm nanofiltered intravenous immunoglobulin. Biologicals. 2010;38:486–493. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2010.02.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Poelsler G., Berting A., Kindermann J., Spruth M., Hämmerle T., Teschner W. A new liquid intravenous immunoglobulin with three dedicated virus reduction steps: virus and prion reduction capacity. Vox Sanguinis. 2008;94:184–192. doi: 10.1111/j.1423-0410.2007.01016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lee D.C., Stenland C.J., Miller J.L.C., Cai K. A direct relationship between partitioning of the pathogenic prion protein and transmissible spongiform encephalopathy infectivity during the purification of plasma proteins. Transfusion. 2000;41:449–455. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.2001.41040449.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Foster P.R., Welch A.G., McLean C., Griffin B.D. Distribution of a bovine spongiform encephalopathy – derived agent over ion – exchange chromatography used in the preparation of concentrates of fibrinogen and factor VIII. Vox Sanguinis. 2004;86:92–99. doi: 10.1111/j.0042-9007.2004.00403.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yunoki M., Tanaka H., Urayama T., Hattori S. Prion removal by nanofiltration under different experimental conditions. Biologicals. 2008;36(1):27–36. doi: 10.1016/j.biologicals.2007.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown P. Donor pool size and the risk of blood-borne Creutzfeldt–Jakob disease. Transfusion. 1998;38(3):312–315. doi: 10.1046/j.1537-2995.1998.38398222878.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]