Graphical abstract

Highlights

► We highlight current knowledge on the plasmodial proteasome. ► We compile evidence for UPS-mediated protein recycling in Plasmodium parasites. ► We discuss the potential role of the proteasome as a multi-stage target for antimalarial drugs.

Keywords: Plasmodium falciparum, Proteasome, Ubiquitin, Inhibitor

Abstract

The ubiquitin/proteasome system serves as a regulated protein degradation pathway in eukaryotes, and is involved in many cellular processes featuring high protein turnover rates, such as cell cycle control, stress response and signal transduction. In malaria parasites, protein quality control is potentially important because of the high replication rate and the rapid transformations of the parasite during life cycle progression. The proteasome is the core of the degradation pathway, and is a major proteolytic complex responsible for the degradation and recycling of non-functional ubiquitinated proteins. Annotation of the genome for Plasmodium falciparum, the causative agent of malaria tropica, revealed proteins with similarity to human 26S proteasome subunits. In addition, a bacterial ClpQ/hslV threonine peptidase-like protein was identified. In recent years several independent studies indicated an essential function of the parasite proteasome for the liver, blood and transmission stages. In this review, we compile evidence for protein recycling in Plasmodium parasites and discuss the role of the 26S proteasome as a prospective multi-stage target for antimalarial drug discovery programs.

1. Introduction

The proteasome is a major proteolytic complex responsible for the degradation and recycling of proteins and therefore plays an important role in intracellular protein quality control. The proteasome mediates the degradation of many short-lived proteins that are involved in cell cycle regulation, signal transduction and apoptosis, and is also responsible for the recycling of abnormal or damaged proteins, which would otherwise accumulate and become harmful to the cell (reviewed in Pickart and Cohen, 2004). The proteasome is part of the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), which manages proteostasis in the cell. Via an UPS-specific enzymatic cascade, proteins become labelled with a small ubiquitin (Ub) tag. The type of ubiquitination then determines whether a protein is designated for further roles in cellular processes like DNA repair, trafficking or signal transduction, or whether it will be degraded by the proteasome (reviewed in Hendil and Hartmann-Petersen, 2004; Pickart and Cohen, 2004; Clague and Urbe, 2010). Because eukaryotic proteostasis is central to cell development, deficiencies can lead to metabolic, oncogenic, neurodegenerative and cardiovascular disorders (reviewed in Balch et al., 2008).

Protein regulation appears to be important for the rapid transformations of the malaria parasite during life cycle progression in target organs of the human host and the mosquito vector, including stages having high replication rates. Shifts in temperature, to which the parasite is exposed when rapidly adapting from human to mosquito, and vice versa, might additionally induce a stress response requiring management by the UPS. In silico predictions indicate that over half of the parasite proteins represent targets for ubiquitination (Ponts et al., 2011). The human malaria parasite, Plasmodium falciparum, appears to possess a functional eukaryotic proteasome and a bacterial ClpQ/hslV threonine peptidase-like protein complex (reviewed in Chung and Le Roch, 2010; Tschan et al., 2011), but their specific roles within the parasite are not known.

The proteasome has long been explored as an anti-cancer drug target (reviewed in Kisselev and Goldberg, 2001), based upon the observation that proteasome inhibition can induce apoptosis preferentially in cancer cells. In 2003 the proteasome inhibitor bortezomib (Velcade®, PS-341) was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of multiple myeloma (Kane et al., 2003). Since then, a stream of new proteasome inhibitors have been pursued in clinical trials (reviewed in Orlowski and Kuhn, 2008; de Bettignies and Coux, 2010).

In Plasmodium, inhibitor studies reveal an essential role of the proteasome for the liver, blood and transmission stages (Gantt et al., 1998; Lindenthal et al., 2005; Reynolds et al., 2007; Kreidenweiss et al., 2008; Prudhomme et al., 2008; Czesny et al., 2009; Schoof et al., 2010; Aminake et al., 2011), thus suggesting the proteasome as a promising multi-stage target in malaria therapy. The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends artemisinin-based combination therapies for the treatment of malaria, with component drugs having independent targets in order to gain control of drug-resistant parasites (WHO Guidelines for the Treatment of Malaria 2010). Ideally, such antimalarials would further exhibit activities against the liver and transmission stages of the pathogen. Inhibitors targeting the plasmodial proteasome might well fulfill these requirements, and antimalarial drug development programs might benefit from developments in anti-cancer proteasome inhibitors having improved specificity, tolerance and bioavailability.

While the Plasmodium proteasome begins to draw attention as an antimalarial drug target, our understanding of protein regulation in malaria parasites remains rudimentary. It is inferred that the structure and function of the plasmodial UPS is similar to other eukaryotes, based on a generally high level of conservation. However, primary data on these assumptions are fragmented, and it is not clear to what degree the UPS has adapted to the requirements of the highly specialized malaria parasite. To reveal detailed function of the parasite UPS, it will be necessary to study UPS-mediated protein regulation and proteasomal degradation of target proteins. This review highlights current knowledge of the plasmodial proteasome; investigates the range of UPS proteins in the parasite; and discusses the potential role of the proteasome as a target for antimalarial drugs.

2. The composition of the proteasome

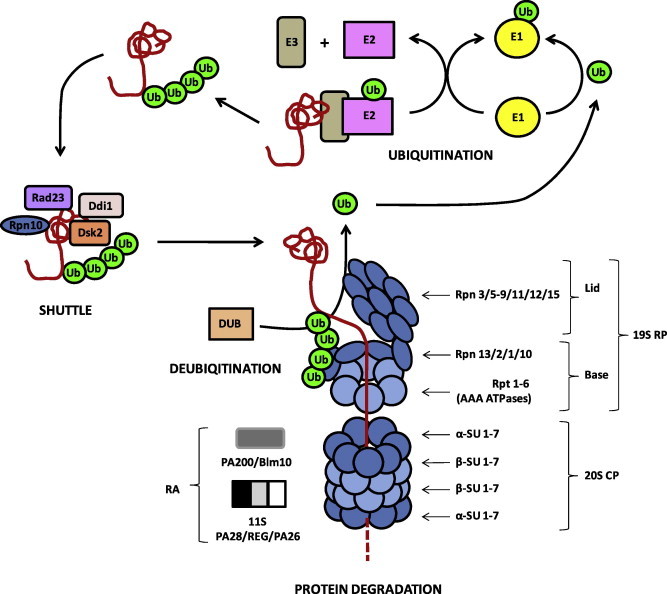

The 26S proteasome is a 2.5 MDa complex involved in the regulated degradation of ubiquitinated proteins. It is composed of more than 33 subunits (SUs), which form a proteolytic barrel-like 20S core particle (CP), capped by two 19S regulatory particles (RPs) (Fig. 1). The RP is involved in ATP-dependent recognition, binding and unfolding of ubiquitinated proteins, while the CP is important for proteolysis (reviewed in Marques et al., 2009; Bedford et al., 2010; Xie, 2010). The CP is formed by four staged heptameric rings: two outer rings, consisting of seven α-SUs per ring, and two inner rings composed of seven β-SUs each. Substrate peptide bonds are hydrolyzed by N-terminal active site threonine residues, which are embedded in the core of the CP’s β-SUs. Three of the seven different β-SUs are proteolytically active; namely, β1, β2 and β5, displaying caspase-, trypsin-, and chymotrypsin-like activities, respectively (Arendt and Hochstrasser, 1997; Heinemeyer et al., 1997). More recent data suggest that the performance of the different active sites are interdependent and may have specific functional relevance (Kisselev et al., 2006; Britton et al., 2009).

Fig. 1.

The UPS of eukaryotes. The schematic depicts the structure of the 26S proteasome as well as protein ubiquitination, shuttle and deubiquitination, as experimentally demonstrated in human and yeast. UPS proteins identified in P. falciparum are framed in black, proteins without homologs in P. falciparum are framed in grey. CP, core particle; DUB, deubiquitinating enzyme; E, ubiquitinating enzyme; RA, regulatory activator; RP, regulatory particle; SU, subunit; Ub, ubiquitin.

Because the proteolytic sites are sequestered in the closed barrel, activators are required to facilitate access to the CP, thus ensuring that protein degradation occurs only if the substrate is unfolded (reviewed in Gallastegui and Groll, 2010). In addition to the 19S RP, it was shown for the human and yeast proteasomes that the CP is able to associate with one of two known ATP-independent activators, the 11S/PA28 heteroheptamer complex and the large heat-repeat containing protein PA200/Blm10 (reviewed in Stadtmüller and Hill, 2011). While 11S/PA28 and PA200/Blm10 are reported to preferentially support hydrolysis of peptides, the RP is involved in the degradation of proteins with higher complexity (reviewed in O’Donoghue and Gordon, 2006).

The CP can associate with one or two of the 19S RPs. The RP recognizes the ubiquitinated protein, assists in deubiquitination and unfolds the substrate, which is subsequently translocated into the CP cavity. The RP is divided into two sub-complexes, the base and the lid (Fig. 1; reviewed in Bedford et al., 2010; Gallastegui and Groll, 2010). The RP base comprises six different AAA-type ATPase SUs, the regulatory particle triple A proteins (Rpt1-6), as well as four non-ATPase SUs, the regulatory particle non-ATPase proteins Rpn1, Rpn2, Rpn10 and Rpn13. Rpn10 and Rpn13 are ubiquitin receptors, while Rpn1 and Rpn2 function as scaffold. Rpn10 acts as a linker protein between the base and the lid. The lid consists of nine Rpn-type SUs; namely, Rpn3, Rpn5-9, Rpn11, Rpn12 and Rpn15.

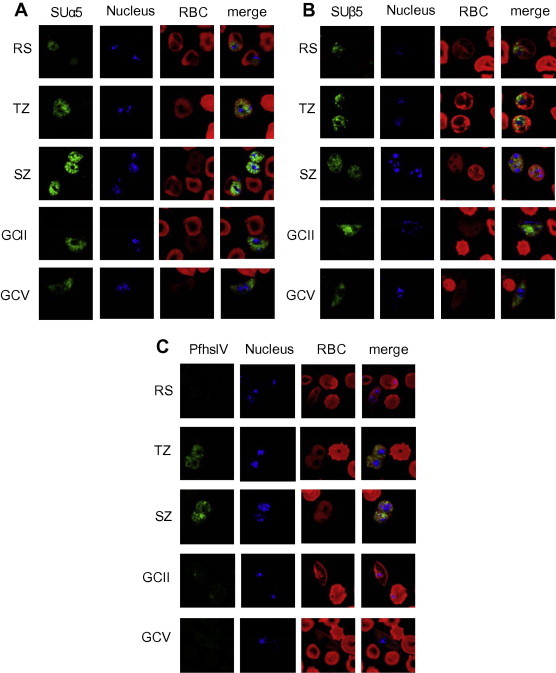

In P. falciparum, 14 putative proteins homologous to the yeast CP were identified (Mordmüller et al., 2006). CP-SUs α5 and β5 were recently shown to be present in the cytoplasm and nucleus of blood stage parasites, particularly in trophozoites and schizonts (Fig. 2A, B; Aminake et al., 2011; Aminake and Pradel, unpublished observations). This is in accordance with recent findings reporting a peak of ubiquitinated proteins in these stages (Ponts et al., 2011). The proteasome is further expressed in gametocytes of both genders during their differentiation from stage I to stage V (Fig. 2A, B; Aminake et al., 2011; Aminake and Pradel, unpublished observations), pointing to high protein turnover activities in these stages.

Fig. 2.

(A) Subcellular localization of proteasome SUs and of PfhslV in the blood and gametocyte stages of P. falciparum. Indirect immunofluorescence assays, using mouse polyclonal antisera against α-SU type 5 (A) and β-SU type 5 (B) revealed localization of the two proteins in the asexual blood stages as well as in the gametocyte stages (stages IIb and V depicted). Antibodies antisera against PfhslV (C) labeled the protein in the trophozoite and schizont stages, but not in gametocytes (green). Nuclei were highlighted by Hoechst nuclear staining (blue); and erythrocytes were counterstained by Evans Blue (red). GC, gametocyte; RBC, red blood cell; RS; ring stage, SZ, schizont; TZ, trophozoite. Bar, 5 μm. For detailed methods, see Supplementary data. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

In order to identify parasite homologs to proteasomal SUs, we performed a BLAST search using human proteasome SU proteins (http://www.uniprot.org) as queries against the P. falciparum 3D7 genome (http://plasmodb.org; Aurrecoechea et al., 2009). Predicted homologs of proteasome precursor or SU sequences were ranked as having high score segment pairs and low P-values. The computational analysis revealed plasmodial homologs for all of the human 26S proteasome SUs (Table 1). These in silico results provide a first indication for the presence of a 26S proteasome in malaria parasites. Biochemical studies will be required to provide direct evidence for the physical presence, interaction and proteolytic activities of the predicted SUs.

Table 1.

Homologs of human proteasome subunits α and β identified in P. falciparum.

| Proteasome subunits | Homo sapiens (accession number) | P. falciparum (Plasmodb code) | Identities (%) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CP subunitso | ||||

| Proteasome subunit α type 1 | P25786 | PF14_0716 | 44 | 8.7 e−52 |

| Proteasome subunit α type 2 | P25787 | PFF0420c | 57 | 3.2 e−70 |

| Proteasome subunit α type 3 | P25788 | PFC0745c | 34 | 3.7 e−44 |

| Proteasome subunit α type 4 | P25789 | PF13_0282 | 53 | 3.4 e−66 |

| Proteasome subunit α type 5 | P28066 | PF07_0112 | 54 | 5.5 e−66 |

| Proteasome subunit α type 6 | P60900 | MAL8P1.128 | 45 | 3.1 e−56 |

| Proteasome subunit α type 7 | O14818 | MAL13P1.270 | 53 | 2.6 e−59 |

| Proteasome subunit β type 1 | P20618 | PFE0915c | 43 | 4.0 e−47 |

| Proteasome subunit β type 2 | P49721 | PF14_0676 | 37 | 6.3 e−33 |

| Proteasome subunit β type 3 | P49720 | PFA0400c | 43 | 3.7 e−44 |

| Proteasome subunit β type 4 | P28070 | MAL8P1.142 | 42 | 6.0 e−41 |

| Proteasome subunit β type 5 | P28074 | PF10_0111 | 53 | 1.2 e−59 |

| Proteasome subunit β type 6 | P28072 | PFI1545c | 29 | 8.3 e−27 |

| Proteasome subunit β type 7 | Q99436 | PF13_0156 | 53 | 1.6 e−66 |

| RP base subunits | ||||

| 26S protease regulatory subunit 7 or RPT1 | P35998 | PF13_0063 | 70 | 1.2 e−159 |

| 26S protease regulatory subunit 4 or RPT2 | P62191 | PF10_0081 | 77 | 1.5 e−168 |

| 26S protease regulatory subunit 6B or RPT3 | P43686 | PFD0665c | 64 | 4.6 e−133 |

| 26S protease regulatory subunit 10B or RPT4 | P62333 | PF13_0033 | 67 | 2.8 e−142 |

| 26S protease regulatory subunit 6A or RPT5 | P17980 | PF11_0314 | 71 | 7.3 e−158 |

| 26S protease regulatory subunit 8 or RPT6 | P62195 | PFL2345c | 74 | 2.0 e−155 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 2 or RPN1 | Q13200 | PFB0260w | 37 | 1.5 e−143 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 1 or RPN2 | Q99460 | PF14_0632 | 43 | 1.3 e−161 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 4 or RPN10 | P55036 | PF08_0109 | 41 | 4.6 e−37 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit RPN13 | Q16186 | PF14_0138 | 35 | 6.6 e−17 |

| RP lid subunits | ||||

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 3 or RPN3 | O43242 | MAL13P1.190 | 35 | 3.4 e−73 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 12 or RPN5 | O00232 | PF10_0174 | 39 | 1.6 e−82 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 4 or RPN6 | O00231 | PF14_0025 | 35 | 5.3 e−51 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 6 or RPN 7 | Q15008 | PF11_0303 | 37 | 1.1 e−76 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 7 or RPN8 | P51665 | PFI0630w | 39 | 9.3 e−55 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 13 or RPN9 | Q9UNM6 | PF10_0298 | 26 | 1.2 e−38 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 14 or RPN 11 | O00487 | MAL13P1.343 | 63 | 1.2 e−100 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit 8 or RPN 12 | P48556 | PFC0520w | 32 | 1.6 e−25 |

| 26S proteasome non-ATPase regulatory subunit RPN 15 or DSS1 | P60896 | MAL7P1.117 | 61 | 0.53 |

We further identified a homolog to the human ATP-independent activator 11S/PA28, PFI0370c, showing an identity of 33% (P-value of 2.1e−24), indicating that the plasmodial CP might also be regulated independently from the RP. No homolog of PA200/Blm10 was identified.

3. HslV: ancestral relict or essential enzyme?

In addition to homologs of the eukaryotic proteasome SUs, a predicted bacteria-like proteasomal predecessor was identified with similarity to ClpQ/hslV threonine peptidase of Escherichia coli, which was termed PfhslV (PFL1465c; Mordmüller et al., 2006). Bacterial HslV exhibits moderate sequence similarities with eukaryotic β-SUs (Rohrwild et al., 1996). The threonine peptidase typically associates with the ATPase HslU, and the HslV/U complex consists of two inner rings of six HslV-SUs per ring and two outer rings of six HslU-SUs each. In E. coli, HslV is involved in the degradation of regulatory or misfolded proteins, but it appears unessential for the bacterium (Missiakas et al., 1996; Kanemori et al., 1997; Seong et al., 1999). In P. falciparum, an HslU homolog, PfhslU (PFI0355c), was recently identified and in silico analyses predicted an interaction between PfhslU and PfhslV (Subramaniam et al., 2009).

The HslV threonine-peptidase has been identified in a variety of protists (reviewed in Tschan et al., 2011), including localization within the kinetoplast of Trypanosoma brucei, where it is involved in replication of mitochondrial minicircles (Li et al., 2008). In P. falciparum, PfhslV was originally described to localize to the cytoplasm of blood stage parasites, where it is proteolytically active and exhibiting threonine protease, chymotrypsin-like and peptidyl glutamyl peptide hydrolase activities (Ramasamy et al., 2007). A follow-up study assigned the nucleus-encoded PfhslV to the mitochondrion, to which it is transported by an N-terminal targeting sequence (Tschan et al., 2010).

While PfhslV is abundantly expressed in the asexual blood stages, new data from our laboratory indicate that PfhslV expression decreases in gametocytes (Fig. 2C; Aminake and Pradel, unpublished observations). Considering that in gametocytes the mitochondrion becomes highly branched (Okamoto et al., 2009) while the parasite shifts from glycolysis towards mitochondrial respiration (van Dooren et al., 2006), the down-regulation of the mitochondrion-assigned enzyme in these stages warrants future study.

The attractiveness of PfhslV as a drug target is based on the absence of a homolog in the human host (Ramasamy et al., 2007). However, it is not clear whether PfhslV is essential for the blood stages or other life cycle stages of Plasmodium parasites. It might be investigated if protease/proteasome inhibitors, discussed below in Section 7, exert their effect on PfhslV instead of the 26S proteasome. Reverse genetics approaches to disrupt the PfhslV gene locus should shed light on these questions, and within the next years we can expect to better understand the prokaryotic proteasome.

4. Ubiquitin-tagging of proteins

Protein degradation is triggered by the carboxy-terminal tagging of the 76 amino acid long protein Ub to surface-exposed lysine residues of redundant or misfolded proteins, thereby marking them for degradation by the proteasome. Once the initial Ub is attached, poly-ubiquitination of the substrate can occur through the sequential transfer of additional Ubs. Substrates targeted for degradation require an Ub chain of at least four residues. Proteins might also be mono-ubiquitinated at single or multiple sites without being targeted for degradation, and then function in cellular signaling processes like DNA repair, endocytosis or trafficking (reviewed in Hicke, 2001; Hofmann, 2009; Clague and Urbe, 2010; Grabbe et al., 2011).

Ub can be isolated as an 8.5 kDa protein from the cell either by degradation of poly-Ub proteins or by proteolytic cleavage of Ub-fusion proteins. In P. falciparum, a poly-ubiquitin encoding gene, pfpUb, comprises five tandem repeats of the Ub open reading frame (Table 2; Horrocks and Newbold, 2000). PfpUb is expressed in all life cycle stages with a predominant expression in intraerythrocytic parasites (Bozdech et al., 2003; Le Roch et al., 2003). Genes encoding two additional Ub-fusion proteins are present in P. falciparum, the uba52 homolog L40/UBI and S31/UBI (Table 2; Ponts et al., 2008). The Ubs are fused to ribosomal proteins L40 and S27a. The P. falciparum genome also encodes for an 8.5 kDa Nedd8 ortholog, an ubiquitin-like protein (ULP) which becomes covalently conjugated to a limited number of cellular proteins in a manner analogous to ubiquitination. Lastly, the genome encodes for a number of additional ULPs, including homologs to SUMO, Hub1, Urm1 and Atg8 (Table 2; Ponts et al., 2008). Proteins conjugated by ULPs are generally not targeted for degradation by the proteasome, but rather function in diverse regulatory activities.

Table 2.

UPS components identified in P. falciparum.

| UPS component | Plasmodb code | UPS component | Plasmodb code |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ub and ULPsa | E3 Ub-ligasesa | ||

| polyUb | PFL0585w | HECT | MAL8P1.23 |

| L40/UBI | PF13_0346 | HECT | PF11_0201 |

| S31/UBI | PF14_0027 | HECT | MAL7P1.19 |

| Nedd8 | MAL13P1.64 | HECT | PFF1365c |

| SUMO | PFE0285c | Cullin | PF08_0094 |

| Hub1 | PFL1830w | Cullin | PFF1445c |

| Atg8 | PF10_0193 | F-box | PFF0960c |

| Urm1 | PF11_0393 | F-box | PFF0710w |

| E1 Ub-activating enzymesa | F-box | PFL1565c | |

| UBA1 | PFL1245w | U-box | PF08_0020 |

| UBA2 | PFL1790w | U-box | PFC0365w |

| UBA3 | MAL8P1.75 | U-box | PF07_0026 |

| UBA4 | PF13_0344 | RING finger | PFL2440w |

| UBA1-like | PF13_0182 | RING finger | PF11_0330 |

| Atg7 | PF11_0271 | RING finger | PFI0470w |

| Other | PF13_0264 | RING finger | MAL13P1.405 |

| Other | PF11_0457 | RING finger | PFE1490c |

| E2 Ub-conjugating enzymesa | RING finger | PF14_0215 | |

| UBC9 | PFI0740c | RING finger | PFF1325c |

| UBC12 | PFL2175w | RING finger | PFC0610c |

| UBC13 | PFE1350c | RING finger | PFL0275w |

| UEV | PFC0255c | RING finger | PFF0165c |

| Other | PFL0190w | RING finger | PF10_0117 |

| Other | PF13_0301 | RING finger | PF11_0244 |

| Other | PFF0305c | RING finger | PFF0355c |

| Other | PF10_0330 | RING finger | PF10_0046 |

| Other | PF08_0085 | RING finger | PF14_0054 |

| Other | PFC0855w | RING finger | PFC0740c |

| Other | PFI1030c | RING finger | PF10_0276 |

| Other | PFL2100w | RING finger | PFD0765w |

| Other | PF14_0128 | RING finger | PF10_0072 |

| Other | MAL13P1.227 | RING finger | PFE0610c |

| DUBsa | RING finger | PFB0440c | |

| UCH | PF13_0096 | RING finger | PFC0510w |

| UCH | PFE0835w | RING finger | MAL13P1.216 |

| UCH | MAL7P1.147 | RING finger | PFL0440c |

| UCH | PFD0655c | RING finger | PF13_0188 |

| UCH | PFA0220w | RING finger | PFE0100w |

| UCH | PF14_0145 | RING finger | PF14_0416 |

| UCH | PFD0165w | RING finger | PFF1180w |

| UCH | PFI0225w | RING finger | PFF0755c |

| PfUCHL3 | PF14_0576 | RING finger | MAL13P1.302 |

| PfUCH54 | PF11_0177 | RING finger | MAL13P1.345 |

| USP14 | PFE1355c | RING finger | MAL7P1.155 |

| Josephin | PFL1295w | RING finger | PFC0690c |

| Josephin | PF11_0125 | RING finger | PFL1705w |

| Mov34 | MAL13P1.343 | RING finger | PFC0845c |

| Mov34 | PFI0630w | RING finger | PFI0805w |

| Mov34 | PFI0895c | RING finger | PFL1620w |

| Mov34 | PFD0265w | RING finger | PFC0175w |

| Mov34 | PF10_0233 | RING finger | PF14_0139 |

| Mov34 | PF11_0409 | RING finger | PFC0425w |

| DUF862 | PFL0865w | RING finger | MAL13P1.224 |

| DUF862 | PF10_0069 | RING finger | MAL13P1.122 |

| DUF862 | PFI0940c | Shuttle proteins | |

| OTU | PF10_0308 | Rad23 | PF10_0114 |

| OTU | PFI1135c | Dsk2 | PF11_0142 |

| OTU | PF11_0428 | Ddi1 | PF14_0090 |

| WLM | PF10_0092 | ||

| Peptidase_C48 | PFL1635w | ||

| Peptidase_C48 | MAL8P1.157 | ||

| Peptidase_C54 | PF14_0171 | ||

Modified from Ponts et al. (2008).

Ub conjugation involves three groups of serially-connected enzymes, the Ub-activating enzyme E1, the Ub-conjugating enzyme E2 and the Ub ligase E3 (Fig. 1). In an initial step, E1 binds Ub to form an Ub-E1 thioester and transfers the residue to E2. Subsequently, E3 interacts with both E2 and the target protein, resulting in the transfer of Ub from E2 to the substrate lysine residue. Unlike E1 and E2, the E3 enzymes are specific to the protein substrate. The E3 ligases provide substrate selectivity through a specific substrate recognition domain or via other cofactors; and can accordingly be divided into four major classes, the HECT, the RING, the PHD and the U-box E3 enzymes (reviewed in Shi and Grossman, 2010).

In P. falciparum, eight putative E1-like enzymes, 14 putative E2-like enzymes and 54 putative E3 ligases were identified (Table 2; Ponts et al., 2008, reviewed in Chung and Le Roch, 2010). Only limited information is available on the functionality of these enzymes in malaria parasites. A homolog for the Ub-conjugating enzyme 13 was identified in P. falciparum (PfUBC13, Table 2), and it was shown that the PfUBC13 activity is regulated by the protein kinase PfPK9 (Philip and Haystead, 2007). Le Roch and co-workers recently reported ubiquitination activity and an essential function of three of the parasite-specific E3 ligases (Chung and Le Roch, 2010). The authors pointed out that these enzymes might represent a prospective novel type of drug target due to their high divergence and essentiality for the malaria parasite. In accordance with this statement, recent studies on the human E3 ligase MDM2 and the small molecule inhibitor MI-63 indicated that the targeted inhibition of E3 enzymes can be achieved (Canner et al., 2009).

The transport of ubiquitinated substrate to the proteasome is mediated by shuttle proteins (Fig. 1). Rpn10, described above as a 19S RP base protein, is also present in the cell without any proteasome association and appears to function as a substrate shuttle. Other extra-proteasomal Ub-binding proteins functioning as shuttles are Rad23, Dsk2 or Ddi1 (reviewed in Hartmann-Petersen and Gordon, 2004; Madura, 2004; Welchman et al., 2005). These proteins contain an Ub-like domain UbL, which can bind to the Ub receptors of the proteasome, as well as the Ub-binding domain, UbA (reviewed in Bedford et al., 2010). Orthologs of Rad23, Dsk2 and Ddi1 (Table 2) can be identified in P. falciparum; namely, PF10_0114, PF11_0142 and PF14_0090, exhibiting 29%, 27% and 34% identities, respectively (P-values of 1.0 e−24, 5.2 e−34 and 3.5 e−32).

As the delivery of Ub-tagged proteins to the proteasome is essential for proteolysis, drug targeting of the shuttle proteins would in theory be an attractive approach to interfere with the UPS. However, little is known on their suitability as drug targets. One compound, termed girolline, is linked with blocking the delivery of Ub-tagged proteins to the proteasome (Tsukamoto et al., 2004). However, its exact mode of action is not well known, and in malaria parasites could also involve translation termination (Benoit-Vical et al., 2008).

5. Protein deubiquitination

Prior to degradation by the proteasome, the Ubs are removed from the substrate to make them available for subsequent ubiquitination cycles. Ub removal is mediated by de-ubiquitinating enzymes (DUBs; Fig. 1). DUBs are proteases involved in ULP maturation, Ub removal and pUb chain editing (proof-reading; reviewed in Bedford et al., 2011). While some DUBs disassemble Ub chains non-specifically, the majority of them exhibit substrate-specificity. In humans, DUBs are classified into five conserved families, JAMM, UCH, USP, OTU and MJD. All DUBs are cysteine proteases, with the exception of the JAMM zinc metalloproteases (reviewed in Shi and Grossman, 2010).

The 19S RP lid component Rpn11 exhibits de-ubiquitinating activity. Other DUBs are not part of the proteasome, but interact with the complex (proteasome-interacting proteins, PIPs; reviewed in Xie, 2010); among them Ubp6/USP14 and Uch2/Uch37 of yeast and human. Uch2/Uch37 interacts with the proteasomal Ub receptor Rpn13, and both Ubp6/USP14 and Uch2/Uch37 may serve as “proof-reading” enzymes to remove Ub chains from proteins that are mistakenly encountered and ubiquitinated by the UPS (reviewed in Kraut et al., 2007).

In P. falciparum, two independent studies identified 18 and 29 DUBs, respectively (Table 2; Ponder and Bogyo, 2007; Ponts et al., 2008). Homologs of human UCH37, PfUCH54; and of UCHL3, PfUCHL3 (Table 2), were identified in P. falciparum and known to exhibit deubiquitinating and deNeddylating activities (Artavanis-Tsakonas et al., 2006, 2010; Frickel et al., 2007). A putative homolog of human USP14 (PFE1355c) is also present in P. falciparum (33% identities, P-value = 6.9 e−43).

Due to their intrinsic protease activity, plasmodial DUBs might represent excellent targets for antimalarial drug discovery. Parasite cysteine proteases have been of interest due to their involvement in hemoglobin degradation (reviewed in Rosenthal, 2011). Comprehensive studies in malaria parasites would be feasible to determine the effect on Ub-protein accumulation of antiplasmodial cysteine protease inhibitors and currently available DUB inhibitors (such as Ubal, UbVS or cyclopentenon; reviewed in Daviet and Colland, 2008). The deNeddylating activities of PfUCH54 and PfUCHL3 might be of particular interest for drug design, since such activity is not known for the mammalian homologs of the two DUBs.

6. Inhibitors of the 20S proteasome

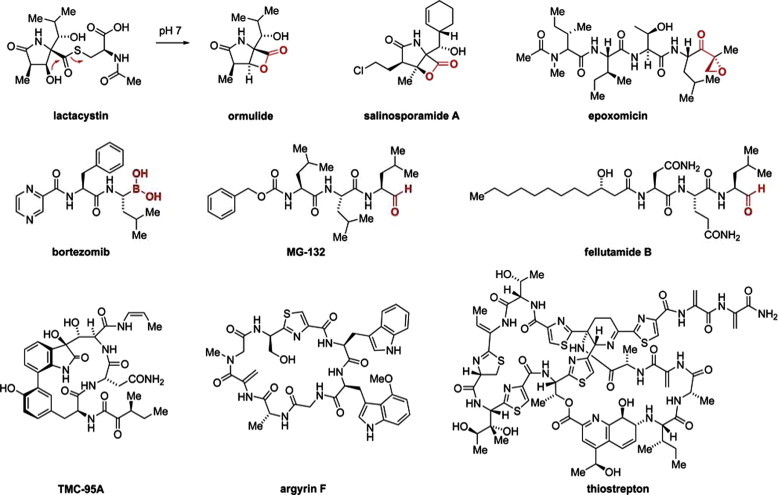

Several distinct kinds of proteasome inhibitors can be discerned (reviewed in Verdoes et al., 2009). First, chemically reactive β-lactone natural products such as lactacystin or salinosporamide A have been found (Fig. 3). These mechanism-based “suicide” inhibitors undergo covalent attachment to the threonine in the active centers of the β-SUs by nucleophilic opening of the β-lactone ring. For lactacystin, the β-lactone containing intermediate ormulide is formed slowly in situ from its cystein thioester. These compounds are of high appeal in basic science, but their reactive promiscuity and high toxicity render potential applications remote.

Fig. 3.

Chemical structures of proteasome inhibitors. Functional groups undergoing covalent attachment to the proteasome active centers are highlighted in red. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Secondly, a large variety of substrate mimetics has been reported which emulate the endogenous peptides processed by the proteasome and thereby achieve higher selectivity amongst other cellular proteases. Both natural products (epoxomicin, fellutamide B) and designed compounds (MG-132, bortezomib) have been developed and intensively characterized (Fig. 3), in some cases leading to success in the clinic (bortezomib). Most of these substrate-competitive molecules carry a chemically reactive “warhead” at the C-terminus to deactivate the proteasome (e.g. epoxyketone, aldehyde, boronic acid) intermittently or even irreversibly. However, recently reversible high-affinity inhibitors of this kind have been reported as well (Blackburn et al., 2010), which do not undergo a covalent attachment. Furthermore, by appropriate tailoring of the chemical structures, subsite-specificity for the CP-SUs β1, β2, or β5 was achieved (Britton et al., 2009).

Thirdly, several complex natural products of the cyclic peptide (argyrins) or peptide alkaloid type (TMC compounds, thiostrepton) inhibit proteasome function (Fig. 3). Apparently, none of these inhibitors undergoes covalent attachment to the proteasome, but rather high activity was found for these compounds or their derivatives. In the case of the argyrins, efficacy in cancer-focused animal models was demonstrated (Nickeleit et al., 2008). While the binding site for TMC-95A was structurally characterized and found to be located at the active centers of the β-SUs (Groll et al., 2006), the site of action is much less clear for argyrin and thiostrepton. Both compounds are quite large and might not easily pass the entry rim formed by the α-SUs. Hence, although potential binding of argyrin at the active centers was recently suggested by molecular modeling (Stauch et al., 2010), other less direct or allosteric modes of action could also be involved, especially for thiostrepton derivatives.

Overall, the intense search for drug candidates in the anti-cancer area has generated a constant stream of non-covalent and covalent inhibitors of the 20S proteasome, accompanied by constantly improving structural data. While it remains to be clarified to which degree functional or molecular inter-species selectivity between humans and Plasmodium parasites can be achieved, this broad basis of bioactive lead compounds with broadly tested toxicity profiles will be highly useful in the future to inspire new compound designs and support screening campaigns in Plasmodium infection models.

7. The plasmodial proteasome: a multi-stage drug target?

Due to the essential roles of the UPS in all eukaryotic cells, one might expect that proteasome inhibitors show activities against malaria parasites as well. While it was shown in yeast and human that the CP-SUs β1, β2 and β5 display caspase-like, trypsin-like and chymotrypsin-like activities, respectively, such distinct activities have not been confirmed for Plasmodium, and interaction of active site-targeting inhibitors with CP-SUs have yet to be demonstrated. However, epoxomicin was reported to bind parasite CP-SUs β2 and β5 (Mordmüller et al., 2006) and bortezomib, which exhibits antiplasmodial activities, has a high specificity for β5 (Oerlemans et al., 2008), providing indirect evidence for the proteolytically active sites of the plasmodial proteasome.

Among active-site targeting proteasome inhibitors, lactacystin, salinosporamide A, MG 132, epoxomicin, and bortezomib were tested for efficacy against P. falciparum and reported to inhibit parasite growth in vitro at low nanomolar concentrations (Table 3; Gantt et al., 1998; Reynolds et al., 2007; Kreidenweiss et al., 2008; Prudhomme et al., 2008; Aminake et al., 2011). Proteasome inhibitors are fast acting, and drug-treated parasites were reported to be arrested prior to DNA replication (Reynolds et al., 2007; Kreidenweiss et al., 2008; Aminake et al., 2011), thus at a time point when protein ubiquitination is at a peak (Ponts et al., 2011). Ubiquitinated protein accumulation was observed in the parasite lysate after treatment of the parasite with proteasome inhibitors, providing indirect evidence that the proteasome is affected (Lindenthal et al., 2005; Aminake et al., 2011).

Table 3.

The antimalarial effect of selected proteasome inhibitors.

| Liver stages (100% inhibition) [μM] | Blood stages (IC50) [μM] | Gametocytes (100% elimination) [μM] | Transmission (100% reduction) [μM] | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bortezomib | n.d. | 0.03–0.56c,d | n.d. | n.d. |

| Epoxomicin | n.d. | 0.002–0.03d,g | 0.03f,g | 0.1f |

| Lactacystin | 9.0a | 1.2–1.5a | n.d. | n.d. |

| MG-132 | n.d. | 0.04–0.05e,g | 0.5g | n.d. |

| MLN273 | 1.0b | 0.04b | n.d. | n.d. |

| Salinosporamide A | n.d. | 0.01e | n.d. | n.d. |

| Thiostrepton | n.d. | 8.9–16.7g | 8.9g | n.d. |

n.d., not determined.

In addition to their effect on blood stage parasites, the proteasome inhibitors lactacystin and MLN273 (a compound related to bortezomib) were reported to have an effect on the liver stages in vitro, when applied in the micromolar range (Table 3; Gantt et al., 1998; Lindenthal et al., 2005). Both inhibitors blocked the development of exoerythrocytic forms in liver hepatoma cells in vitro, and lactacystin was further shown to inhibit infectivity in the P. berghei mouse model in vivo (Gantt et al., 1998). The effect of other proteasome inhibitors on the liver stages of Plasmodium has not been tested. Few antimalarials known to target liver stage are available; for example, the 8-aminoquinolines primaquine and tafenoquine. The fact that proteasome inhibitors exhibit activities against the liver and blood stages, makes them particularly interesting for malaria therapy. MG-132 and epoxomicin were recently reported to exhibit gametocytocidal activities in vitro in their IC50-90 concentrations, thereby eliminating the gametocytes from the cultures within two days of drug incubation, and in consequence reducing parasite transmission from the human to the mosquito (Table 3; Czesny et al., 2009; Aminake et al., 2011). Gametocytocidal activities have been demonstrated for few antimalarials, including primaquine and artemisinin (Pukrittayakamee et al., 2004). The development of novel antimalarials with gametocytocidal activities is therefore urgently needed and is currently promoted by the WHO and the Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation.

Gametocytes are the sexual precursor cells of the malaria parasite, which form in the human blood in response to stress, and likely other unknown cues (reviewed in Talman et al., 2004). Gametocytes develop from stage I to stage V during a period of approximately 10 days, before continuing their life cycle in the mosquito vector (reviewed in Pradel, 2007; Kuehn and Pradel, 2010). When investigating the gametocytocidal effect of epoxomicin in detail, we recently observed that the inhibitor exerted its effect on gametocytes during maturation from the early to the mature stages (Aminake et al., unpublished observations). The maturation of gametocytes is accompanied by high protein turnover rates, which is particularly reflected by the sequential expression of a high number of surface-associated proteins, like Pfs16, Pfs230, Pfs48/45 and the LCCL-domain proteins (reviewed in Pradel, 2007; Kuehn and Pradel, 2010), and these changes in the composition of surface proteins might be regulated by the plasmodial UPS.

Thiostrepton was recently identified as an inhibitor of the proteasome, although the compound was described in the 1950s as a strong antibiotic with high activity against Gram-positive strains (reviewed in Bagley et al., 2005) and is used as a topical antibiotic in veterinary medicine. Its activity is mediated by tight binding to the GTPase-associated region of the bacterial 70S ribosome, which then stalls during protein translocation (Harms et al., 2008; Jonker et al., 2011). Due to genetic and functional similarity of the ribosomes in bacteria and eukaryotic organelles, thiostrepton impairs protein biosynthesis in the mitochondrion and in the apicoplast of malaria parasites (McConkey et al., 1997; Tarr et al., 2011). However, the rapid killing induced by thiostrepton and its derivatives is contrary to the delayed death effect of other apicoplast-targeting antibiotics (reviewed in Pradel and Schlitzer, 2010), and this might be explained by invoking an additional target. The target was recently identified as the proteasome by cell microscopy, enzymatic activity studies and phenotype profiling (Schoof et al., 2010; Aminake et al., 2011). While thiostrepton exhibits only moderate antiplasmodial activities in vitro, derivatives are active in the low micromolar range (Table 2; Schoof et al., 2010; Aminake et al., 2011). Taken together, thiostrepton derivatives combine in one molecular structure two modes of action against P. falciparum, and this unique duality might reduce the likelihood of resistance.

8. Future perspectives

The plasmodial proteasome can be viewed as a candidate multi-stage drug target, and progression of our understanding might benefit from the experience and reagents gained during the development of anti-cancer proteasome inhibitors. It will nonetheless remain challenging to identify inhibitors which are sufficiently specific to the microorganism; that is, with a high therapeutic index allowing treatment of human malaria. In the case of aggressively dividing myeloma a sufficient therapeutic window was found for bortezomib, which suggests that proteasome inhibitors could become an effective treatment or at least component for an acute therapy against the rapidly developing blood stages of Plasmodium. To reach a sufficient therapeutic index and to target also the more hidden and diluted liver and gametocyte stages, species-selective agents would be highly desirable. Along this line, encouraging data was recently reported for Mycobacterium tuberculosis, for which a species-selective proteasome inhibitor was found (Lin et al., 2009). Therefore, further characterization of the biochemistry and cell biology of the UPS in Plasmodium will not only help unravel its unique biology in a multi-stage parasitic organism, but also potentially enable the discovery of new antimalarial drugs.

Acknowledgements

We thank Tom Templeton for critical review of the manuscript. G.P. and H.-D.A. gratefully acknowledge the Emmy-Noether Young Investigator awards from the Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft (DFG). M.N.A. was supported by the IRTG1522 of the DFG (to G.P.).

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The document containing the supplementary data.

References

- Aminake M.N., Schoof S., Sologub L., Leubner M., Kirschner M., Arndt H.D., Pradel G. Thiostrepton and derivatives exhibit antimalarial and gametocytocidal activity by dually targeting parasite proteasome and apicoplast. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011;55:1338–1348. doi: 10.1128/AAC.01096-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arendt C.A., Hochstrasser M. Identification of the yeast 20S proteasome catalytic centers and subunit interactions required for active-site formation. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1997;94:7156–7161. doi: 10.1073/pnas.94.14.7156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas K., Misaghi S., Comeaux C.A., Catic A., Spooner E., Duraisingh M.T., Ploegh H.L. Identification by functional proteomics of a deubiquitinating/deNeddylating enzyme in Plasmodium falciparum. Mol. Microbiol. 2006;61:1187–1195. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2958.2006.05307.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Artavanis-Tsakonas K., Weihofen W.A., Antos J.M., Coleman B.I., Comeaux C.A., Duraisingh M.T., Gaudet R., Ploegh H.L. Characterization and structural studies of the Plasmodium falciparum ubiquitin and Nedd8 hydrolase UCHL3. J. Biol. Chem. 2010;285:6857–6866. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.072405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aurrecoechea C., Brestelli J., Brunk B.P., Dommer J., Fischer S., Gajria B., Gao X., Gingle A., Grant G., Harb O.S., Heiges M., Innamorato F., Iodice J., Kissinger J.C., Kraemer E., Li W., Miller J.A., Nayak V., Pennington C., Pinney D.F., Roos D.S., Ross C., Stoeckert C.J., Jr, Treatman C., Wang H. PlasmoDB: a functional genomic database for malaria parasites. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009;37:D539–543. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagley M.C., Dale J.W., Merritt E.A., Xiong X. Thiopeptide antibiotics. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:685–714. doi: 10.1021/cr0300441. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Balch W.E., Morimoto R.I., Dillin A., Kelly J.W. Adapting proteostasis for disease intervention. Science. 2008;319:916–919. doi: 10.1126/science.1141448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford L., Paine S., Sheppard P.W., Mayer R.J., Roelofs J. Assembly, structure, and function of the 26S proteasome. Trends Cell. Biol. 2010;20:391–401. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2010.03.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedford L., Lowe J., Dick L.R., Mayer R.J., Brownell J.E. Ubiquitin-like protein conjugation and the ubiquitin-proteasome system as drug targets. Nat. Rev. Drug Discov. 2011;10:29–46. doi: 10.1038/nrd3321. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benoit-Vical F., Salery M., Soh P.N., Ahond A., Poupat C. Girolline: a potential lead structure for antiplasmodial drug research. Planta Med. 2008;74:438–444. doi: 10.1055/s-2008-1034348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackburn C., Gigstad K.M., Hales P., Garcia K., Jones M., Bruzzese F.J., Barrett C., Liu J.X., Soucy T.A., Sappal D.S., Bump N., Olhava E.J., Fleming P., Dick L.R., Tsu C., Sintchak M.D., Blank J.L. Characterization of a new series of non-covalent proteasome inhibitors with exquisite potency and selectivity for the 20S beta5-subunit. Biochem. J. 2010;430:461–476. doi: 10.1042/BJ20100383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bozdech Z., Llinas M., Pulliam B.L., Wong E.D., Zhu J., DeRisi J.L. The transcriptome of the intraerythrocytic developmental cycle of Plasmodium falciparum. PLoS Biol. 2003;1:E5. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0000005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Britton M., Lukas M., Downey S.L., Screen M., Pletnev A.A., Verdoes M., Tokhunts R.A., Amir O., Goddard A.L., Pelphrey P.M., Wright D.L., Overkleeft H.S., Kisselev A.F. Selective inhibitor of proteasome’s caspase-like sites sensitizes cells to specific inhibition of chymotrypsin-like sites. Chem. Biol. 2009;16:1278–1298. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2009.11.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Canner J.A., Sobo M., Ball S., Hutzen B., DeAngelis S., Willis W., Studebaker A.W., Ding K., Wang S., Yang D., Lin J. MI-63: a novel small-molecule inhibitor targets MDM2 and induces apoptosis in embryonal and alveolar rhabdomyosarcoma cells with wild-type p53. Br. J. Cancer. 2009;101:774–781. doi: 10.1038/sj.bjc.6605199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chung D.W., Le Roch K.G. Targeting the Plasmodium ubiquitin/proteasome system with anti-malarial compounds: promises for the future. Infect. Disord. Drug Targets. 2010;10:158–164. doi: 10.2174/187152610791163345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clague M.J., Urbe S. Ubiquitin: same molecule, different degradation pathways. Cell. 2010;143:682–685. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2010.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Czesny B., Goshu S., Cook J.L., Williamson K.C. The proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin has potent Plasmodium falciparum gametocytocidal activity. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2009;53:4080–4085. doi: 10.1128/AAC.00088-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daviet L., Colland F. Targeting ubiquitin specific proteases for drug discovery. Biochimie. 2008;90:270–283. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2007.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Bettignies G., Coux O. Proteasome inhibitors: dozens of molecules and still counting. Biochimie. 2010;92:1530–1545. doi: 10.1016/j.biochi.2010.06.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frickel E.M., Quesada V., Muething L., Gubbels M.J., Spooner E., Ploegh H., Artavanis-Tsakonas K. Apicomplexan UCHL3 retains dual specificity for ubiquitin and Nedd8 throughout evolution. Cell. Microbiol. 2007;9:1601–1610. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-5822.2007.00896.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallastegui N., Groll M. The 26S proteasome: assembly and function of a destructive machine. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2010;35:634–642. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2010.05.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gantt S.M., Myung J.M., Briones M.R., Li W.D., Corey E.J., Omura S., Nussenzweig V., Sinnis P. Proteasome inhibitors block development of Plasmodium spp. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2731–2738. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.10.2731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grabbe C., Husniak K., Dikic I. The spatial and temporal organization of ubiquitin networks. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2011;12:295–307. doi: 10.1038/nrm3099. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groll M., Gotz M., Kaiser M., Weyher E., Moroder L. TMC-95-based inhibitor design provides evidence for the catalytic versatility of the proteasome. Chem. Biol. 2006;13:607–614. doi: 10.1016/j.chembiol.2006.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harms J.M., Wilson D.N., Schlünzen F., Connell S.R., Stachelhaus T., Zaborowska Z., Spahn C.M., Fucini P. Translational regulation via L11: molecular switches on the ribosome turned on and off by thiostrepton and micrococcin. Mol. Cell. 2008;30:26–38. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2008.01.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann-Petersen R., Gordon C. Protein degradation: recognition of ubiquitinylated substrates. Curr. Biol. 2004;14:R754–756. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2004.09.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinemeyer W., Fischer M., Krimmer T., Stachon U., Wolf D.H. The active sites of the eukaryotic 20 S proteasome and their involvement in subunit precursor processing. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:25200–25209. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.40.25200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendil K.B., Hartmann-Petersen R. Proteasomes: a complex story. Curr. Protein Pept. Sci. 2004;5:135–151. doi: 10.2174/1389203043379747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hicke L. A new ticket for entry into budding vesicles-ubiquitin. Cell. 2001;106:527–530. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(01)00485-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofmann K. Ubiquitin-binding domains and their role in the DNA damage response. DNA Repair (Amst) 2009;8:544–556. doi: 10.1016/j.dnarep.2009.01.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horrocks P., Newbold C.I. Intraerythrocytic polyubiquitin expression in Plasmodium falciparum is subjected to developmental and heat-shock control. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2000;105:115–125. doi: 10.1016/s0166-6851(99)00174-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jonker H.R.A., Baumann S., Wolf A., Schoof S., Hiller F., Schulte K.W., Kirschner K.N., Schwalbe H., Arndt H.D. NMR structures of thiostrepton derivatives for characterization of the ribosomal binding site. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2011;50:3308–3312. doi: 10.1002/anie.201003582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kane R.C., Bross P.F., Farell A.T., Pazdur R. Velcade((R)): USFDA approval for the treatment of multiple myeloma progressing on prior therapy. Oncologist. 2003;8:508–513. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.8-6-508. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanemori M., Nishihara K., Yanagi H., Yura T. Synergistic roles of HslVU and other ATP-dependent proteases in controlling in vivo turnover of sigma32 and abnormal proteins in Escherichia coli. J. Bacteriol. 1997;179:7219–7225. doi: 10.1128/jb.179.23.7219-7225.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisselev A.F., Goldberg A.L. Proteasome inhibitors: from research tools to drug candidates. Chem. Biol. 2001;8:739–758. doi: 10.1016/s1074-5521(01)00056-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kisselev A.F., Callard A., Goldberg A.L. Importance of the different proteolytic sites of the proteasome and the efficacy of inhibitors varies with the protein substrate. J. Biol. Chem. 2006;281:8582–8590. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M509043200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraut D.A., Prakash S., Matouschek A. To degrade or release: ubiquitin-chain remodeling. Trends Cell. Biol. 2007;17:419–421. doi: 10.1016/j.tcb.2007.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kreidenweiss A., Kremsner P.G., Mordmüller B. Comprehensive study of proteasome inhibitors against Plasmodium falciparum laboratory strains and field isolates from Gabon. Malar. J. 2008;7:187. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-7-187. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuehn A., Pradel G. The coming-out of malaria gametocytes. J. Biomed. Biotechnol. 2010;2010:976827. doi: 10.1155/2010/976827. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Le Roch K.G., Zhou Y., Blair P.L., Grainger M., Moch J.K., Haynes J.D., De La Vega P., Holder A.A., Batalov S., Carucci D.J., Winzeler E.A. Discovery of gene function by expression profiling of the malaria parasite life cycle. Science. 2003;301:1503–1508. doi: 10.1126/science.1087025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Lindsay M.E., Motyka S.A., Englund P.T., Wang C.C. Identification of a bacterial-like HslVU protease in the mitochondria of Trypanosoma brucei and its role in mitochondrial DNA replication. PLoS Pathog. 2008;4:e1000048. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin G., Li D.J., De Cavalho L.P.S., Deng H.T., Tao H., Vogt G., Wu K., Schneider J., Chidawanyika T., Warren J.D., Li H., Nathan C. Inhibitors selective for mycobacterial versus human proteasomes. Nature. 2009;461:621–626. doi: 10.1038/nature08357. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindenthal C., Weich N., Chia Y.S., Heussler V., Klinkert M.Q. The proteasome inhibitor MLN-273 blocks exoerythrocytic and erythrocytic development of Plasmodium parasites. Parasitology. 2005;131:37–44. doi: 10.1017/s003118200500747x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Madura K. Rad23 and Rpn10: perennial wallflowers join the melee. Trends Biochem. Sci. 2004;29:637–640. doi: 10.1016/j.tibs.2004.10.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marques A.J., Palanimurugan R., Mathias A.C., Ramos P.C., Dohmen R.J. Catalytic mechanism and assembly of the proteasome. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:1509–1536. doi: 10.1021/cr8004857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McConkey G.A., Rogers M.J., McCutchan T.F. Inhibition of Plasmodium falciparum protein synthesis: targeting the plastid-like organelle with thiostrepton. J. Biol. Chem. 1997;272:2046–2049. doi: 10.1074/jbc.272.4.2046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Missiakas D., Schwager F., Betton J.M., Georgopoulos C., Raina S. Identification and characterization of HsIV HsIU (ClpQ ClpY) proteins involved in overall proteolysis of misfolded proteins in Escherichia coli. EMBO J. 1996;15:6899–6909. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mordmüller B., Fendel R., Kreidenweiss A., Gille C., Hurwitz R., Metzger W.G., Kun J.F., Lamkemeyer T., Nordheim A., Kremsner P.G. Plasmodia express two threonine-peptidase complexes during asexual development. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2006;148:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2006.03.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nickeleit I., Zender S., Sasse F., Geffers R., Brandes G., Sörensen I., Steinmetz H., Kubicka S., Carlomagno T., Menche D., Gütgemann I., Buer J., Gossler A., Manns M.P., Kalesse M., Frank R., Malek N.P. Argyrin A reveals a critical role for the tumor suppressor protein p27kip1 in mediating antitumor activities in response to proteasome inhibition. Cancer Cell. 2008;14:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2008.05.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Donoghue J.E., Gordon C. Proteasome-interacting proteins. In: Mayer R.J., Ciechanover A., Rechsteiner M., editors. Protein Degradation: The Ubiquitin-Proteasome System. Wiley-VCH; 2006. pp. 157–182. [Google Scholar]

- Oerlemans R., Franke N.E., Assaraf Y.G., Cloos J., van Zantwijk I., Berkers C.R., Scheffer G.L., Debipersad K., Vojtekova K., Lemos C., van der Heijden J.W., Ylstra B., Peters G.J., Kaspers G.L., Dijkmans B.A., Scheper R.J., Jansen G. Molecular basis of bortezomib resistance. proteasome subunit beta5 (PSMB5) gene mutation and overexpression of PSMB5 protein. Blood. 2008;112:2489–2499. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-104950. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Okamoto N., Spurck T.P., Goodman C.D., McFadden G.I. Apicoplast and mitochondrion in gametocytogenesis of Plasmodium falciparum. Eukaryot. Cell. 2009;8:128–132. doi: 10.1128/EC.00267-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlowski R.Z., Kuhn D.J. Proteasome inhibitors in cancer therapy: lessons from the first decade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2008;14:1649–1657. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-07-2218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philip N., Haystead T.A. Characterization of a UBC13 kinase in Plasmodium falciparum. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2007;104:7845–7850. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0611601104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pickart C.M., Cohen R.E. Proteasomes and their kin: proteases in the machine age. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2004;5:177–187. doi: 10.1038/nrm1336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponder E.L., Bogyo M. Ubiquitin-like modifiers and their deconjugating enzymes in medically important parasitic protozoa. Eukaryot. Cell. 2007;6:1943–1952. doi: 10.1128/EC.00282-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponts N., Yang J., Chung D.W., Prudhomme J., Girke T., Horrocks P., Le Roch K.G. Deciphering the ubiquitin-mediated pathway in apicomplexan parasites: a potential strategy to interfere with parasite virulence. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2386. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002386. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ponts N., Saraf A., Chung D.W., Harris A., Prudhomme J., Washburn M.P., Florens L., Le Roch K.G. Unraveling the human malaria parasite’s ubiquitome. J. Biol. Chem. 2011;286:40320–40330. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.238790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradel G. Proteins of the malaria parasite sexual stages: expression, function and potential for transmission blocking strategies. Parasitology. 2007;134:1911–1929. doi: 10.1017/S0031182007003381. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pradel G., Schlitzer M. Antibiotics in malaria therapy and their effect on the parasite apicoplast. Curr. Mol. Med. 2010;10:335–349. doi: 10.2174/156652410791065273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prudhomme J., McDaniel E., Ponts N., Bertani S., Fenical W., Jensen P., Le Roch K. Marine actinomycetes: a new source of compounds against the human malaria parasite. PLoS One. 2008;3:e2335. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0002335. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pukrittayakamee S., Chotivanich K., Chantra A., Clemens R., Looareesuwan S., White N.J. Activities of artesunate and primaquine against asexual- and sexual-stage parasites in falciparum malaria. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2004;48:1329–1334. doi: 10.1128/AAC.48.4.1329-1334.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramasamy G., Gupta D., Mohmmed A., Chauhan V.S. Characterization and localization of Plasmodium falciparum homolog of prokaryotic ClpQ/HslV protease. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2007;152:139–148. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2007.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds J.M., El Bissati K., Brandenburg J., Gunzl A., Mamoun C.B. Antimalarial activity of the anticancer and proteasome inhibitor bortezomib and its analog ZL3B. BMC Clin. Pharmacol. 2007;7:13. doi: 10.1186/1472-6904-7-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rohrwild M., Coux O., Huang H.C., Moerschell R.P., Yoo S.J., Seol J.H., Chung C.H., Goldberg A.L. HslV-HslU: A novel ATP-dependent protease complex in Escherichia coli related to the eukaryotic proteasome. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 1996;93:5808–5813. doi: 10.1073/pnas.93.12.5808. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenthal P.J. Falcipains and other cysteine proteases of malaria parasites. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 2011;712:30–48. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4419-8414-2_3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schoof S., Pradel G., Aminake M.N., Ellinger B., Baumann S., Potowski M., Najajreh Y., Kirschner M., Arndt H.D. Antiplasmodial thiostrepton derivatives: proteasome inhibitors with a dual mode of action. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:3317–3321. doi: 10.1002/anie.200906988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seong I.S., Oh J.Y., Yoo S.J., Seol J.H., Chung C.H. ATP-dependent degradation of SulA, a cell division inhibitor, by the HslVU protease in Escherichia coli. FEBS Lett. 1999;456:211–214. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(99)00935-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shi D., Grossman S.R. Ubiquitin becomes ubiquitous in cancer: emerging roles of ubiquitin ligases and deubiquitinases in tumorgenesis and as therapeutic targets. Cancer Biol. Ther. 2010;10:737–747. doi: 10.4161/cbt.10.8.13417. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stadtmüller B.M., Hill C.P. Proteasome activators. Mol. Cell. 2011;41:8–19. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2010.12.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stauch B., Simon B., Basile T., Schneider G., Malek N.P., Kalesse M., Carlomagno T. Elucidation of the structure and intermolecular interactions of a reversible cyclic-peptide inhibitor of the proteasome by NMR spectroscopy and molecular modeling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2010;49:3934–3938. doi: 10.1002/anie.201000140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Subramaniam S., Mohmmed A., Gupta D. Molecular modeling studies of the interaction between Plasmodium falciparum HslU and HslV subunits. J. Biomol. Struct. Dyn. 2009;26:473–479. doi: 10.1080/07391102.2009.10507262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Talman A.M., Domarle O., McKenzie F.E., Ariey F., Robert V. Gametocytogenesis: the puberty of Plasmodium falciparum. Malar. J. 2004;3:24. doi: 10.1186/1475-2875-3-24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tarr S.J., Nisbet R.E., Howe C.J. Transcript-level responses of Plasmodium falciparum to thiostrepton. Mol. Biochem. Parasitol. 2011;179:37–41. doi: 10.1016/j.molbiopara.2011.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschan S., Kreidenweiss A., Stierhof Y.D., Sessler N., Fendel R., Mordmüller B. Mitochondrial localization of the threonine peptidase PfHslV, a ClpQ ortholog in Plasmodium falciparum. Int. J. Parasitol. 2010;40:1517–1523. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpara.2010.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tschan S., Mordmüller B., Kun J.F. Threonine peptidases as drug targets against malaria. Expert Opin. Ther. Targets. 2011;15:365–378. doi: 10.1517/14728222.2011.555399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsukamoto S., Yamashita K., Tane K., Kizu R., Ohta T., Matsunaga S., Fusetani N., Kawahara H., Yokosawa H. Girolline, an antitumor compound isolated from a sponge, induces G2/M cell cycle arrest and accumulation of polyubiquitinated p53. Biol. Pharm. Bull. 2004;27:699–701. doi: 10.1248/bpb.27.699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Dooren G.G., Stimmler L.M., McFadden G.I. Metabolic maps and functions of the Plasmodium mitochondrion. FEMS Microbiol. Rev. 2006;30:596–630. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2006.00027.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Verdoes M., Florea B.I., van der Marel G.A., Overkleeft H.S. Chemical tools to study the proteasome. Eur. J. Org. Chem. 2009;20:3301–3313. [Google Scholar]

- Welchman R.L., Gordon C., Mayer R.J. Ubiquitin and ubiquitin-like proteins as multifunctional signals. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2005;6:599–609. doi: 10.1038/nrm1700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xie Y. Structure, assembly and homeostatic regulation of the 26S proteasome. J. Mol. Cell. Biol. 2010;2:308–317. doi: 10.1093/jmcb/mjq030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

The document containing the supplementary data.