Abstract

The eyes are our window to the world and offer us an island of vision in the sea of darkness. Equally, the eyes are also a window to peep into what is going on in the milieu interior.

Pregnancy is a natural state of physiological stress for the body. Each organ system of the body in a pregnant lady behaves at variation than in a non-pregnant state. A complex interplay exists between how the pregnancy affects the eye and how ocular physiology and pathology may lead to the modification of the management of pregnancy. Added to this is the effect of systemic conditions on the eye which gets modified by pregnancy.

An awareness of the interaction of Ophthalmology and Obstetrics for the benefit of the mother and the child requires a basic understanding of these complex interactions. This article aims at presenting to the reader in a simplified and organized manner the common ophthalmic issues encountered in a pregnant woman, their management and the effect of various ophthalmic medication on the fetus.

Keywords: Eye diseases in pregnancy, Pregnancy complications, Pregnancy physiology

“The woman about to become a mother, or with her newborn infant upon her bosom, should be the object of trembling care and sympathy wherever she bears her tender burden or stretches her aching limbs…. God forbid that any member of the profession to which she trusts her life, doubly precious at that eventful period, should hazard it negligently, unadvisedly or selfishly.”

- Oliver Wendell Holmes

Introduction

Pregnancy is a physiological situation which places abnormal stress and demands on a body otherwise maintained in harmony between the milieu interior and exterior, with or without medications. Each organ system of the body in a pregnant lady behaves at variation than in a non-pregnant state. The physiological, hematological, hormonal, immunological, metabolic changes in the body of a pregnant lady merit a special consideration, as also the eye.1 The maternal endocrine system and the placenta (the hormone factory) along with other changes cause ocular abnormalities which are reversible and rarely permanent.

In pregnancy, the risks to the fetus preclude the conduction of certain tests, mainly invasive. In addition various, pre-existing diseases in a non-pregnant lady may behave differently, some getting aggravated or ameliorated. The prescription to a pregnant lady also requires special considerations.

The effects of pregnancy on the eye can be divided into:

-

1.

The physiological changes which occur during pregnancy

-

2.

Disorders of the eye occurring due to pregnancy

-

3.

Disorders of the eye already present but getting modified by the pregnancy.

Any or all of these can lead to visual symptoms (Table 1). The following paragraphs bring out these vagaries involved in treating ophthalmic disorders in a pregnant lady1 and the effect of use of various ophthalmic drugs on the fetus.

Table 1.

Causes of vision loss in pregnancy.

|

Physiological ophthalmic changes in pregnancy

Intra Ocular Pressure (IOP) modifying changes

The IOP is known to decline in pregnancy to the tune of 10%, with the peak decline in the 12th to 18th week in the ocular hypertensive group. This drop may last for several months post-partum period.2 The pregnant ladies also have a reduced diurnal fluctuation in their IOP as compared to their pre-pregnancy diurnal variation.3

This drop in IOP in pregnancy is a result of an increased outflow facility, caused by an increased uveo-scleral outflow and a decrease in the episcleral venous pressure consequent to the decreased venous pressure in the upper part of the body. While, pregnancy induced acidosis adds to this IOP fall, change in ocular rigidity is not a factor in this IOP fall as the measurements by indentation and applanation have been comparable. Thus the pre-existing glaucoma tends to improve during the pregnancy. Hørven and Halvard found a moderate decrease in intra ocular pressure during both the second part of pregnancy and the first two months after delivery.

Dynamic tonometry performed in pregnant women revealed increased corneal indentation pulse (CIP) amplitudes in the first part of pregnancy, however, a steady decrease occurred thereafter until the CIP amplitudes at term measured one third of the non-pregnant value.2 The CIP amplitudes were still below the normal average half a year after delivery. The form of the CIP amplitudes changed in pregnancy, with a marked decrease in the relative crest time during the entire pregnancy and was so characteristic that the authors suggested that dynamic tonometry might be introduced as a diagnostic test for pregnancy!

Eyelids & conjunctiva

Chloasma, the “mask of pregnancy” is generally limited to the cheeks, but may extend on to the eyelids and fades post-partum. Conjunctival blood vessels show an increased granularity due to the decreased blood flow rate.

Cornea & refraction

The corneal sensitivity progressively decreases in pregnancy and reaches its pre-pregnancy levels 4–6 weeks after delivery. A 3% increase in corneal thickness with insignificant fluctuation through each trimester of pregnancy has been seen and its return to baseline thickness shortly after delivery suggests a hormonal influence on corneal fluid retention.4 This increase in pachymetry values is thought to be due to corneal edema, and this also causes a change in refractive index of the cornea, thus changing the refraction. A pregnant contact lens user might land up with contact lens intolerance due to increased corneal thickness, altered tear composition and consequent corneal edema. It is ideal to abstain from contact lenses during pregnancy and early post-partum and if unavoidable refitting with a custom made soft contact lenses 1.2 mm flatter than flat K. For this reason, prescription/re-prescription of spectacles should be deferred till at least 2 months post-partum. Laser surgery for the refraction correction is contraindicated.

In pregnancy, Krukenberg's spindle is seen without the associated outflow obstruction or rise in IOP (Fig. 1). This occurs generally in the first two trimesters of pregnancy and the spindle decreases in size or vanish in the third trimester and early post-partum period. The increased outflow facility and the increased progesterone levels inherent in the third trimester help in clearing the pigment from the angle, preventing an IOP rise.2

Fig. 1.

Slit Lamp photograph of Krukenberg spindle in a pregnant lady (POG 22 5/7 weeks).

There is a transient loss of accommodation in pregnancy and occasionally accommodative weakness and paralysis has been described during lactation. Tear production tends to decrease during the pregnancy with altered composition leading to dry eyes, infection and local trauma.

Visual fields

There is a physiological increase in the size of the pituitary gland in pregnancy, but this increase itself is not sufficient to cause a visual field defect unless accompanied by an abnormal anatomical relationship between the optic chiasma and the pituitary gland. Various, visual field changes like bitemporal contraction, concentric contraction have been noted in studies. If visual field loss is a symptom with which the patient reports, she merits investigation for unmasked tumors.5

Pathological ophthalmic conditions occuring in pregnancy

Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (CSCR)

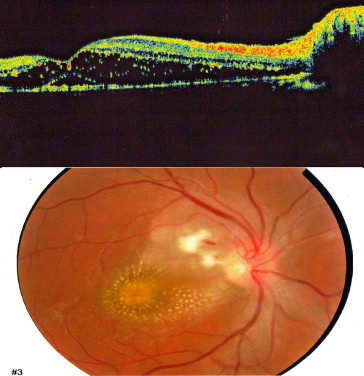

CSCR is universally considered to be a disease of the males (10:1), one might not think of the diagnosis of CSCR in a pregnancy. The onset of visual symptoms usually occurs during the third trimester. CSCR should be considered in a pregnant patient complaining of diminution of vision, central scotoma or metamorphopsia especially if systemic steroids have been exhibited for any associated disease. CSCR during pregnancy is usually associated with white sub retinal exudation surrounding the RPE detachment. CSCR development in pregnancy has been attributed to multiple factors such as hemodynamic and hormonal alterations, hypercoagulability, increased vascular permeability, decreased colloidal osmotic pressure, and changes in prostaglandin levels. Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) is the investigation of choice.6 The detachment resolves spontaneously toward the end of the pregnancy or soon after delivery. CSCR may or may not recur during subsequent pregnancies (Fig. 2).7

Fig. 2.

Fundus photograph and Optical Coherence Tomography (OCT) of a pregnant lady who developed Central Serous Chorioretinopathy (CSCR). The lady was on oral steroids and steroid skin ointment for a dermatological condition (POG 32 2/7 weeks).

Uveal melanoma

Incidence of ocular melanoma and reactivation of quiescent melanomas has been noted to be higher in pregnant women when compared to age matched non-pregnant women.8 More recent studies have found no evidence of any hormonal dependence on uveal melanomas, unlike cutaneous melanomas.9

Hypertension and pregnancy

Hypertension and pregnancy can co-exist in varied scenarios. A previously normotensive lady may develop hypertension on conceiving or may aggravate the pre-existing hypertension.10 Pre-eclampsia is a term used for hypertension along with proteinuria after 20 weeks POG. Extremes of maternal age, parity, multifetal pregnancy and concurrent diabetes mellitus, chronic hypertension and renal disease are independent risk factors. Eclampsia is the occurrence of convulsions in a pre-eclamptic patient. Pregnancy aggravated hypertension is pre-eclampsia or eclampsia superimposed on chronic hypertension.

The visual symptoms are in the form of transient scotoma, diplopia, diminution of vision and photopsiae. These ocular symptoms may be features of impeding seizure in a pre-eclamptic patient, particularly in the post-partum period. Although, light stimuli gives a risk of precipitating seizures, an ophthalmoscopic examination should not be avoided since retinal changes mirror placental vascular changes and in-utero sustained vascular insufficiency may cause permanent changes in the fetus. These changes are attributed to change in the hormonal milieu, endothelial damage, hypoperfusion ischemia, hyperperperfusion edema and abnormal auto-regulation.

The retinal changes of pre-eclampsia are the same as those of hypertensive retinopathy, except that they occur over a much shorter span of time. The earliest changes are focal arteriolar spasms, which occur in 50–100% of pre-eclamptic patients followed by arteriolar attenuation. These changes are reversible. This is followed by the appearance of hemorrhages, soft exudates, and in severe cases retinal edema and papilledema.7 A positive correlation has been established between the degree of retinopathy, the severity of pre-eclampsia, maternal blood pressure and fetal mortality.

Exudative retinal detachment (RD) occurs in advanced cases of pre-eclampsia/eclampsia. It is seen in 1% of pre-eclamptic patients and 10% eclamptic patients.7 The detachment is generally bilateral, bullous, and sometimes cyst like and localized. The presence of RD in a pregnant lady has no deleterious effect on the fetus. It occurs due to choroidal vascular changes. Fundus Flourescein Angiography shows areas of focal choroidal non-perfusion and flourescein leakage. After the RD settles, Elschnig pearl like spots are seen representing focal choroidal infarcts. The prognosis is good.

Transient cortical blindness has been noted in eclampsia and severe pre-eclampsia in late pregnancy and early post-partum. This is caused by cerebral edema and returns to normal in a few weeks. MRI shows hyperintense and hypointense signals on T2 and T1 weighted images respectively.1

Over a period of the last three decades, there has been a paradigm shift in the indications for termination of pregnancy based on maternal ophthalmic conditions. This has occurred mainly due to better survival rates of smaller and premature babies due to rapid strides in neonatal care prompting the obstetrician to bring out the baby before the mother or baby suffers any permanent damage on one hand and the ability of modern medicine to tackle much of the pregnancy linked morbidity much more effectively without jeopardizing maternal or fetal well being on the other hand.

Due to this there can be no watertight list of indications for termination of pregnancy and the decision will have to be taken by the obstetrician and the ophthalmologist in unison. The generally accepted indications for termination of pregnancy include:

-

1.

Fetal safety-severe retinopathy with rapidly progressing arteriospasm denotes a compromise in the maternal circulation and is a harbinger of poor fetal prognosis, and is therefore an indication for termination of pregnancy.7a

-

2.

Maternal safety – the presence of extensive cotton–wool spots in all quadrants and long standing arteriolar changes indicate maternal vascular and renal compromise. As these changes regress on termination, there is a case for termination of pregnancy if fetus has reached a stage of viability.1

-

3.

Presence of diabetes mellitus and/or renal disease leading to a severe sight threatening proliferative retinopathy with an imminent risk of vitreous hemorrhage.7a

Disseminated Intra-vascular Coagulation (DIC)

DIC occurs in obstetric complications like, placenta abruptio, retained products of conception and severe pre-eclampsia. Ophthalmic changes generally occur in the choroid due to thrombotic occlusion of the capillaries leading to RPE atrophy and serous retinal detachment over the involved areas causing partially reversible diminution of vision.11

Thrombotic Thrombocytopenic Purpura (TTP)

Ocular changes occur in 10% of TTP patients. The ophthalmic changes include serous RD, retinal hemorrhages, exudates and arteriolar constriction. Anisocoria, subconjunctival hemorrhage, scintillating scotoma and extra-ocular muscle paresis may be present.12 Homonymous hemianopia and optic atrophy may also be seen if vessels supplying optic nerve are involved.

Amniotic fluid embolism

It is a disastrous event which occurs during labor, delivery or early post-partum period with 85% mortality. It presents with chills, cyanosis, convulsions and shock. It can cause Central Retinal Artery Occlusion (CRAO).13 Due to rapid worsening in the patient's condition, little attention has been given to ocular changes.

Antiphospholipid antibody syndrome (APLA)

APLA is a condition with a thrombophilic state and patients are prone to recurrent arterial and/or venous thrombosis. Ocular manifestations may present in the form of vascular thrombosis of the retina, the choroid, the optic nerve and visual pathway, and ocular motor nerves.14

Ptosis

Ptosis, generally aponeurotic, presents or gets aggravated in pregnancy due to increased interstitial fluid and hormonal effects.15

Hyperemesis gravidarum

Severe hyperemesis gravidarum can lead to Wernicke's encephalopathy with nystagmus, extra-ocular muscle palsies which generally resolve with treatment using vitamin supplements.

Optic neuropathy

The optic neuropathy encountered in pregnancy is generally ischemic due to the hypercoagulable state associated with pregnancy. This is linked to increased incidence of Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (AION). Also, severe APH/PPH can cause a Posterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy (PION).16

Idiopathic Intra-cranial Hypertension (IIH)

IIH is known to get precipitated/aggravated in pregnancy due to increased weight gain and managed by keeping a strict check on the weight gain.17

Purtscher's retinopathy

Patients complain of decreased vision, often from 20/200 (6/60) to counting fingers. Fundus examination usually reveals numerous white retinal patches or confluent cotton–wool spots around the disc, as well as superficial retinal hemorrhages.18 A Purtscher's-like fundus picture may occur in nontraumatic settings, like acute pancreatitis, chronic renal failure, and labor.

Effect of pregnancy on pre-existing ocular conditions

Diabetic retinopathy

Pregnancy is a major and independent risk factor for the development and progression of diabetic retinopathy. Various studies give conflicting results regarding the effect of diabetes on pregnancy and pregnancy on diabetes, but there is general consensus on the following aspects.19

-

1.

Gestational diabetes is not at risk for Diabetic Retinopathy (DR).

-

2.

Diabetic ladies need to plan their pregnancies in the third decade and need to be counseled regarding the same. The risk of diabetes related complications increases exponentially with increasing maternal age.

-

3.

Tight diabetic control is required during the peri-natal period. Increased severity of diabetic retinopathy has shown to adversely affect the outcome of pregnancy in form of congenital malformations or fetal deaths.

-

4.In all diabetic pregnant ladies, a baseline ophthalmic examination needs to be done in the first trimester of pregnancy. Further follow up needs to be planned according to the ocular condition:

-

a.No DR/Mild Non Proliferative Diabetic Retinopathy (NPDR): two large studies have found no increase in the DR during pregnancy in a majority of the patients. A repeat ophthalmic examination is required in the third trimester or whenever the patient has visual complaints.

-

b.Moderate NPDR: the DR is seen to worsen with or without macular edema in the second trimester and regress in the third trimester and post-partum. Ophthalmic examination is recommended once in every trimester.

-

c.Severe NPDR: there is an increase in the number of cotton–wool spots and blot haemorrhages in the second trimester which regresses in the post-partum period. Ophthalmic examination is recommended once every 2–3 months.19

-

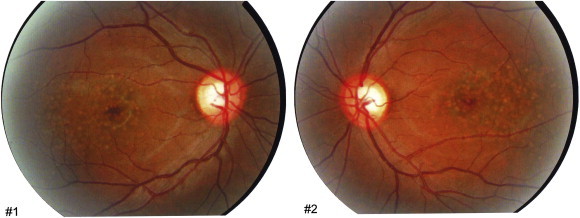

d.Proliferative diabetic retinopathy (PDR): it is ideal to treat the PDR prior to conception. Parity has no influencing effect on the progress of PDR. A pregnant lady with neo-vascularisation in the retina is at an increased risk of vitreous hemorrhage during labor and delivery due to the valsalva phenomenon. However, PDR is not an indication for termination of pregnancy. Pan-retinal photocoagulation (PRP) is equally effective. PDR should be completely treated with PRP with green laser till the neo-vascularization regresses or an elective LSCS should be performed when the pregnancy reaches term. Repeated Fundus Fluorescein Angiography (FFA) is not recommended, fluorescein being in Class C of drugs. Ophthalmic examination is recommended every month (Fig. 3).

-

a.

Fig. 3.

Retinal pigment epithelial changes in the macula of both eyes of a pregnant lady (POG 33 weeks) who had severe pre-eclampsia. The baseline fundoscopy of the same patient in the first trimester was normal.

Intra-cerebral tumors

Pituitary adenoma

In pregnancy, the pituitary gland increases in volume by about 30% above the pre-gestational levels due to the increase in prolactin secreting cells. Similarly a pre-existing pituitary adenoma may also increase in size to become symptomatic during pregnancy.20 The diagnosis of pituitary adenoma is made when the patient is pregnant and develops headache, visual disturbances, bitemporal field defects, diminution of vision and diplopia. If a pituitary adenoma is detected during pregnancy, careful observation suffices, unless the symptoms develop early in pregnancy and there is increasing visual field defect, decreasing visual acuity unexplained by any other reason and a decreased Kistenbaum count of small vessels on the optic nerve.

The accepted modality of treatment of pituitary adenomas is surgery and bromocriptine. No increase in the risk to fetus has been found in patients on bromocriptine. Steroids are used as a short term measure to decrease the size of the tumor in pregnancy.

All patients on treatment for Amenorrhea should be screened for pituitary tumors radiologically and serologically (Prolactin levels) prior to inducing ovulation. If adenoma is detected, it is prudent to watch for a few months to see if it grows. If there appears to be no growth, ovulation may be induced safely.

Meningioma

A pre-existing meningioma may present in the latter half of the pregnancy due to the growth and increased vascularity of the tumor. Estrogen and progesterone receptors have been attributed for the same.21

Grave's disease

Thyroid associated ophthalmopathy may present/get aggravated in early pregnancy with amelioration in the third trimester and resurgence in the post-partum period. Propylthiouracil is the drug of choice for these patients (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4.

Gadolinium enhanced MRI of a lady with Thyroid Associated Ophthalmopathy (TAO) who had an acute exacerbation of proptosis and diplopia two weeks after delivering a live healthy girl child.

Posterior scleritis

Posterior scleritis is known to get aggravated during pregnancy.16 The standard treatment of posterior scleritis is oral steroids. In pregnancy a posterior subtenon injection of triamcinolone is drug of choice. Recurrences are more common in pregnancy.1

Vogt Koyanagi Harada syndrome (VKH)

VKH is characterized by bilateral granulomatous panuveitis, exudative retinal detachments, meningeal signs, hearing loss, and pigment loss. It tends to regress or totally disappear during pregnancy and post-partum.22

Immunological diseases

There is an improvement in both ocular and systemic manifestations of the sarcoidosis, spondyloarthropathy, rheumatoid arthritis during pregnancy probably due to the increased amount of endogenous corticosteroids during pregnancy. Post-partum recurrence or flare-ups are noticeable.

Latent ocular toxoplasmosis

This may reactivate during pregnancy in the mother. Spiramycin is used which is safe and effective.23 The risk to the fetus of congenital toxoplasmosis in these cases is negligible.

Effects of ophthalmic drugs on the fetus

Topical medication use in pregnancy – to ensure a decreased incidence of systemic absorption and toxicity it is advisable to use the minimal concentration and dose. The patient should be told the right way of punctual occlusion, naso-lacrimal pressure and the extra drug should be wiped to prevent systemic absorption.

In-depth knowledge of the effect of ophthalmic medications in pregnancy and lactation is lacking. The recommendations of the National Registry of Drug-Induced Ocular Side Effects are summarized below.24

Glaucoma medications: Beta-blockers should be used with caution in the first trimester of pregnancy and be discontinued 2–3 days prior to delivery to avoid beta-blockade in the infant. Beta-blockers are concentrated in breast milk, hence should be avoided in lactating mothers.

Topical and systemic carbonic anhydrase inhibitors are contraindicated during pregnancy and lactation due to their potential teratogenic effects and hepato-renal effects on the infants.25

Miotics – appear to be safe during pregnancy. Prostaglandins use can lead to abortion and labor induction.

Mydriatics – use of occasional dilating drops during pregnancy for the purposes of ocular examination is safe.

Corticosteroids: Systemic corticosteroids are a relative contraindication in pregnancy due to teratogenecity and their role in CSCR; there are no known teratogenic effects of topical steroids.

Antibiotics and antivirals:-Drugs that are known to be safe during pregnancy include erythromycin, ophthalmic tobramycin, ophthalmic gentamicin, polymyxin B, acyclovir and the quinolones. Antibiotics that should be avoided during pregnancy include the–chloramphenicol, neomycin, and tetracycline.26,27 All topical antivirals should be used with caution during pregnancy and lactation because of teratogenic effects.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Sunness J.S. The pregnant woman's eye. Surv Ophthalmol. 1988;32:219–238. doi: 10.1016/0039-6257(88)90172-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Horven I., Gjonnaess H., Kroese A. Corneal indentation pulse and intraocular pressure in pregnancy. Arch Ophthalmol. 1974;91:92–98. doi: 10.1001/archopht.1974.03900060098002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cantor L.B., Harris A., Harris M. Glaucoma medications in pregnancy. Rev Ophthalmol. 2000:91–99. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Millodot M. The influence of pregnancy on the sensitivity of the cornea. Br J Ophthalmol. 1977;61:646–649. doi: 10.1136/bjo.61.10.646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brewington T.E., Clark C.C., Amin N., Venable H.P. The effect of pregnancy on the peripheral visual field. J Natl Med Assoc. 1974;66:330–331. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Razai K.A., Eliott D. Optical coherence tomographic findings in pregnancy associated central serous chorioretinopathy. Graefes Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol. 2004;242:1014–1016. doi: 10.1007/s00417-003-0850-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perkins Stephen L., Kim Judy E., Pollack John S., Merrill Pauline T. Clinical characteristics of central serous chorioretinopathy in women. Ophthalmology. 2002;109:262–266. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(01)00951-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]; a Singerman L.J., Aiello L.M., Rodman H.M. Diabetic retinopathy: effects of pregnancy and laser therapy. Diabetes. 1980;29(suppl 2):3. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Seddon J.M., MacLaughlin D.T., Albert D.M., Gragoudas E.S., Ference M. Uveal melanomas presenting during pregnancy and the investigation of estrogen receptors in melanomas. Br J Ophthalmol. 1982;66:695–704. doi: 10.1136/bjo.66.11.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Grostern Richard J., Shternfeld Ilona Slusker, Bacus Sarah S., Gilchrist Kennedy, Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study Group Absence of type I estrogen receptors in choroidal melanoma: analysis of Collaborative Ocular Melanoma Study (COMS) eyes. Am J Ophthalmol. 2001;131:788–791. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9394(00)00959-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Thornburg K.L., Jacobson S.L., Giraud G.D., Morton M.J. Hemodynamic changes in pregnancy. Semin Perinatol. 2000;24:11–14. doi: 10.1016/s0146-0005(00)80047-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patchett R.B., Wilson W.B., Ellis P.P. Ophthalmic complications with disseminated intravascular coagulation. Br J Ophthalmol. 1988;72:377–379. doi: 10.1136/bjo.72.5.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Percival S.P. Ocular findings in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (Moschcowitz's disease) Br J Ophthalmol. 1970;54:73–78. doi: 10.1136/bjo.54.2.73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chang M., Herbert W.N. Retinal arteriolar occlusions following amniotic fluid embolism. Ophthalmology. 1984;91:1634–1637. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(84)34092-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Primary anti-phospholipid antibody syndrome (APS)-current concepts. Surv Ophthalmol. 2002;47:215–238. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(02)00289-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sanke R.F. Blepharoptosis as a complication of pregnancy. Ann Ophthalmol. 1984;16:720–722. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dinn R.B., Harris A., Marcus P.S. Ocular changes in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2003;58:137–144. doi: 10.1097/01.OGX.0000047741.79433.52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Huna-Baron R., Kupersmith M.J. Idiopathic intracranial hypertension in pregnancy. J Neurol. 2002;249:1078–1081. doi: 10.1007/s00415-002-0791-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Blodi B.A., Johnson M.W., Gass J.D., Fine S.L., Joffe L.M. Purtscher’s-like retinopathy after childbirth. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:1654–1659. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32365-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheth B.P. Does pregnancy accelerate the rate of progression of diabetic retinopathy? an update. Curr Diab Rep. 2008;8:270–273. doi: 10.1007/s11892-008-0048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Magyar D.M., Marshall J.R. Pituitary tumors and pregnancy. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1978;132:739–748. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(78)80008-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wan W.L., Geller J.L., Feldon S.E., Sadun A.A. Visual loss caused by rapidly progressive intracranial meningiomas during pregnancy. Ophthalmology. 1990;97:18–21. doi: 10.1016/s0161-6420(90)32634-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Nohara M., Norose K., Segawa K. Vogt-Koyanagi-Harada disease during pregnancy. Br J Ophthalmol. 1995;79(1):94–95. doi: 10.1136/bjo.79.1.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Bonfioli A.A., Orefice F. Toxoplasmosis. Semin Ophthalmol. 2005;20:129–141. doi: 10.1080/08820530500231961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on Drugs Transfer of drugs and other chemicals into human milk. Pediatrics. 2001;108:776–789. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Johnson S.M., Martinez M., Freedman S. Management of glaucoma in pregnancy and lactation. Surv Ophthalmol. 2001;45:449–454. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6257(00)00209-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Samples J.R., Meyer S.M. Use of ophthalmic medications in pregnant and nursing women. Am J Ophthalmol. 1988;106:616–623. doi: 10.1016/0002-9394(88)90597-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chung C.Y., Kwok A.K., Chung K.L. Use of ophthalmic medications during pregnancy. Hong Kong Med J. 2004;10:191–195. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]