Graphical abstract

Highlights

► The first report of turtle haemogregarines in Central America. ► 100% prevalence in black river, scorpion mud, and white-lipped mud turtles. ► Surprisingly, higher parasitemias noted in black river turtles compared with white-lipped mud turtles. ► Differences in parasitemia may be due to host natural history or parasite biology.

Keywords: Turtle, Haemoparasite, Haemogregarine, Protozoa, Leech, Vector-borne

Abstract

Twenty-five black river turtles (Rhinoclemmys funerea) and eight white-lipped mud turtles (Kinosternon leucostomum) from Selva Verde, Costa Rica were examined for haemoparasites. Leeches identified as Placobdella multilineata were detected on individuals from both species. All turtles sampled were positive for intraerythrocytic haemogregarines (Apicomplexa:Adeleorina) and the average parasitemia of black river turtles (0.34% ± 0.07) was significantly higher compared to white-lipped mud turtles (0.05% ± 0.006). No correlation was found between parasitemia and relative body mass of either species or between black river turtles from the two habitats. In addition, one scorpion mud turtle (Kinosternon scorpioides) examined from La Pacifica, Costa Rica, was positive for haemogregarines (0.01% parasitemia). Interestingly, parasites of the scorpion mud turtle were significantly smaller than those from the other two species and did not displace the erythrocyte nucleus, whereas parasites from the other two species consistently displaced host cell nuclei and often distorted size and shape of erythrocytes. This is the first report of haemogregarines in turtles from Central America and of haemogregarines in K. leucostomum, K. scorpioides, and any Rhinoclemmys species. Additional studies are needed to better characterise and understand the ecology of these parasites.

1. Introduction

The haemogregarines (Apicomplexa:Adeleorina) are protozoan, intraerythrocytic parasites that infect a wide variety of vertebrates (Davies and Johnston, 2000, Telford, 2009) and are considered common haemoparasites of reptiles. There are currently four recognised genera of haemogregarines that infect reptiles and Haemogregarina is the most common genus reported in aquatic turtles. Since first described in European pond turtles (Emysorbicularis), numerous species of Haemogregarina have been documented; however, description of species based solely on vertebrate host stages is discouraged and should include stages in invertebrate hosts (Ball, 1967, Telford, 2009). In addition, molecular characterisation may provide additional data on host specificity and species diversity (Barta et al., 2012).

Among aquatic turtles, Haemogregarina spp. have been reported from numerous countries in North America, Europe, Asia, and in Australia (Telford, 2009). For haemogregarines with known life cycles, leeches are the invertebrate hosts and vectors for parasites of aquatic turtles and ticks are hosts for parasites of terrestrial reptiles (Siddall and Desser, 1991, Siddall and Desser, 2001, Cook et al., 2009). Although there are no previous reports of haemogregarines in aquatic turtles from Central America, Placobdella leeches have been reported on black river turtles from Costa Rica (Ernst and Ernst, 1977). In addition, haemogregarines have been reported in numerous species of aquatic turtles in North America and the Geoffroy’s Toadhead turtle (Phrynops geoffroanus) in South America (De Campos Brites and Rantin, 2004, Telford, 2009).

Major conservation threats for chelonians in Costa Rica include habitat destruction, use of turtles for food, and harvesting of sea turtle eggs. Excluding sea turtles, there are eight native aquatic/terrestrial turtles in Costa Rica including three species of mud turtles (Kinosternon spp.), two species of wood/river turtles (Rhinoclemmys spp.), two species of sliders (Trachemys spp.), the South American snapping turtle (Chelydra acutirostris), and an introduced, established species (red-eared slider, Trachemys scripta elegans). Data on haemoparasites of aquatic turtles in Central America are scant; therefore, we conducted this study to determine if aquatic turtles of riverine and pond habitats in Selva Verde, Costa Rica, were infected with haemogregarines. Furthermore, because aquatic turtle health may be influenced by parasitism in Costa Rica where natural habitat is shrinking, we determined if habitat or body mass were associated with differences in prevalence or intensity of infection.

2. Methods

2.1. Study site

Selva Verde (10° 27′ 4″N, 84° 4′ 10″W) is a Costa Rican eco-lodge and rainforest reserve that spans 500 acres of the Sarapiquí Canton in the northern Caribbean lowlands (Fig. 1). The reserve has obtained Costa Rica’s Certification for Sustainable Tourism and is dedicated to maintaining biodiversity. However, the reserve itself is bordered by pineapple and banana agriculture to the east and cattle pasture to the west. Black river turtles and white-lipped mud turtles were trapped at two sites within Selva Verde:Site 1 was a natural creek that runs through the reserve and ends in the Sarapiquí River and Site 2 was a small man-made pond located across a highway and 0.45 km from the creek.

Fig. 1.

Satellite image of Selva Verde and surrounding area showing the property of Selva Verde (outlined in yellow) with the creek site marked with narrow arrow and the pond marked with the thick arrow. White bar is 100 m. Inset: map of Costa Rica showing location of Selva Verde (black box) and La Pacifica (black star).

In addition, a single specimen of scorpion mud turtle (Kinosternon scorpioides) was collected from a small creek at La Pacifica (10° 28′ 32″N, 85° 8′ 41″W), an ecological farm and hotel in the Guanacaste Province in western Costa Rica (Fig. 1). This site is classified as a deciduous, dry tropical forest surrounded by fragmented forest and commercial tilapia (Oreochromis niloticus) farms.

2.2. Animal capture and sampling

Turtles were captured in 81 × 51 × 30 cm nylon mesh crab traps (Promar, Gardena, CA) baited with banana, papaya, and tuna. Two traps were used simultaneously at each site. The traps were initially monitored every 50 min at both sites, but the frequency of monitoring was increased to every 15–30 min in the creek due to the higher frequency of captures of black river turtles at this site.

Upon capture, turtles were placed in individual holding containers and the following physical parameters were collected: body weight, curved carapace and plastron length and width. Each individual was identified to species (Savage, 2005), marked with identification numbers on the carapace with nail polish, and photographed. A sample of blood was collected from either the ventral tail vein or the subcarapacial sinus, depending on species, and placed in tubes lined with lithium heparin (Becton, Dickinson and Company, Franklin Lakes, NJ) (Hernandez-Divers et al., 2002). The skin of the head, limbs and tail of each turtle was examined for leeches. Collected leeches were identified using morphologic characters (Sawyer, 1986). All black river turtles were fully examined for leeches, but only two white-lipped mud turtles could be examined because complete physical exams required general anesthesia (5 mg/kg propofol IV; PropoFlo™, Abbott, Abbott Park, IL) to open the double-hinged shell, which proved impractical for the rest of the animals. After processing, all black river turtles and nonanesthetised white-lipped mud turtles were immediately released near the site of capture. The time until release for anesthetised white-lipped mud turtles was increased to three hours to ensure full recovery before return to their normal environment.

Two thin blood smears were immediately made for each turtle, air dried, fixed in 100% methanol, and stained with a modified Giemsa stain (DipQuick, Jorgensen Laboratories, Inc., Loveland, CO). Parasitemia was determined by counting the number of parasites observed during examination of at least 5,000 erythrocytes (Davis and Sterrett, 2011). If no haemogregarines were observed during the first screening, a second count was conducted with the other slide (total of 10,000 erythrocytes examined).

Differences in parasitemia between sites (only for black river turtles) and species were tested using paired t-tests using SAS/STAT, Version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Inc., 2011). A p-value < 0.05 was considered significant. To determine if there was a relationship between parasitemia and body mass (weight (kg)/plastron length (cm)), we graphed both normal and log-transformed data. A single black river turtle collected from the creek habitat was not included in the linear regression analyses due to the lack of body mass data for this specimen.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Physical exams and ectoparasites

A total of 33 turtles were captured from the two sites at Selva Verde, 25 black river turtles from the creek (Site 1; n = 19) and the man-made pond (Site 2; n = 6) and eight white-lipped mud turtles, all from the pond. All turtles appeared healthy but several black river turtles were missing limbs (n = 3), missing a lower beak (n = 1), or had past evidence of shell fracture (n = 5) possibly from intraspecific aggression or attempted predation by spectacled caiman (Caiman crocodilus), which were observed in the creek. Leeches identified as Placobdella multilineata were detected on three black river turtles and one white-lipped turtle, but detailed analysis of the relationship between leech loads and parasitemia was not conducted due to a lack of standardised effort devoted to counting leeches. Interestingly, no ticks were detected on the black river turtles, although a previous study detected Amblyomma sabanerae ticks on this species from Límon, Costa Rica (Ernst and Ernst, 1977). Two P. multilineata were collected from the scorpion mud turtle from La Pacifica.

3.2. Prevalence and parasitemia of haemogregarines

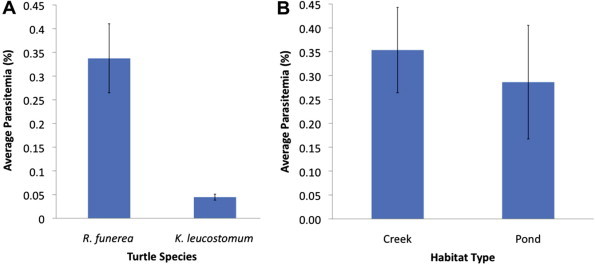

All turtles sampled were positive for haemogregarines (Fig. 2) which represents the first report of haemogregarines in free-ranging aquatic turtles from Central America, specifically Costa Rica. Additionally, this is the first report of haemogregarines in the white-lipped mud turtle, scorpion mud turtle, and the genus Rhinoclemmys. Surprisingly, the average parasitemia of black river turtles (0.34% ± 0.073, maximum 2.2%) was significantly higher than that of white-lipped mud turtles (0.05% ± 0.006, maximum 0.08%) (Fig. 3A) (t = 2.04; df = 31; p = 0.032). The single scorpion mud turtle had a parasitemia of 0.01%.

Fig. 2.

Haemogregarines from black river turtles, Rhinoclemmys funera (A–C) all parasites shown are premeronts except for a meront in B (arrow), white-lipped mud turtle, Kinosternon leucostomum (D–E) premeronts; (F) early meront (arrow), and scorpion mud turtle, K. scorpioides (G–I) all premeronts. Scale bar in panel I is 10 μm and applies to all micrographs.

Fig. 3.

(A) Average haemogregarine parasitemias (±SD) between black river turtles, Rhinoclemmys funerea, collected from creek and pond sites. (B) Average haemogregarine parasitemias (±SD) of black river turtles, Rhinoclemmys funerea, and white-lipped mud turtles, Kinosternon leucostomum, were significantly different (p = 0.032).

The higher average parasitemia in black river turtles, compared with white-lipped mud turtles, did not support our initial hypothesis that predicted basking behaviour would be linked to prevalence and/or intensity of infection. Because black river turtles frequently bask and forage for vegetation out of the water, leech infestation rates were anticipated to be lower, resulting in lower prevalence and/or parasitemia (Moll and Jansen, 1995, Savage, 2005, Readel et al., 2008). This theory has been supported by work in the United States, where basking turtles (Chrysemys picta and/or Trachemys scripta) have lower parasitemias compared with non-basking species (Sternotherus odoratus and/or Chelydra serpentina) (McAuliffe, 1977, Davis and Sterrett, 2011). Alternatively, McCoy et al. (2007) proposed that the total skin surface area of a turtle could be responsible for higher leech burdens by providing more area for parasite attachment. Of our species, black river turtles have unhinged plastrons and were considerably larger than white-lipped mud turtles. Therefore, it is possible that the larger available skin surface area allows more leeches to feed while in the water, overcoming the effects of basking. This may translate to an increased infection with haemogregarines.

The very low parasitemias noted in white-lipped mud turtles (and the single scorpion mud turtle) were surprising. Although no previous work has been conducted on parasitemias of haemogregarines in mud turtles (Kinosternon spp.), we expected high parasitemias based on data from related species in the Family Kinosternidae (e.g., Sternotherus spp.) that have similar behaviour (Herban and Yaeger, 1969, Strohlein and Christensen, 1984, Davis and Sterrett, 2011; Yabsley et al., unpublished). Mud turtles rarely leave the water and/or bask, which should theoretically increase their exposure to leeches (Morales-Verdeja and Vogt, 1997, Savage, 2005). Although the reason for lower parasitemias is not known, one mechanism could be aestivation, a behaviour that white-lipped mud turtles in Mexico undertakes during the dry season (Morales-Verdeja and Vogt, 1997). It is currently unknown if white-lipped mud turtles populations in Costa Rica undergo aestivation.

3.3. Morphology of haemogregarine parasites

Parasites from black river turtles and white-lipped mud turtles were morphologically similar and consistently displaced the host cell nuclei whereas parasites from the scorpion mud turtle never displaced the host cell nuclei (Fig. 2). Premeronts from black river turtles and white-lipped mud turtles measured an average of 12.4 μm ± 0.22 × 6.13 μm ± 0.14 and 12.8 μm ± 0.25 × 6.1 μm ± 0.11, respectively. Interestingly, many of the infected host cells from black river turtles and white-lipped mud turtles were distorted in size and were either elongated (e.g., Fig. 2B, infected cell on left, and Fig. 2E) or were more round (e.g., Fig. 2A and B, infected cell on right; and Fig. 2C, infected cell on right). However, some infected cells were similar in size to uninfected erythrocytes (Fig. 2C, infected cell on left). Premeronts from the scorpion mud turtle (9.8 μm ± 0.5 × 6.1 μm ± 0.25) were significantly shorter than premeronts from the other two turtle species (t = 11.86; df = 8; p < 0.0001). Premeronts were the predominate stage observed in all three turtle species, but rare gamonts (<1%) were also observed in all three species and trophozoites (<1%) were observed in the scorpion mud turtle.

Assignment of parasites to genus was not possible because leeches were not dissected to examine sporogonic stages. Future studies are needed to determine the generic status of the parasites and if they represent different species or pleomorphic forms of a single species, the vectors involved in transmission, and to explore the causative mechanism(s) for the difference in parasitemias between the turtle species.

3.4. Association of body mass and habitat type with parasitemias

No correlation was found between parasitemia and relative body mass in any of the sampled populations, creek-dwelling black river turtles (R2 = 4.5 × 10−5; df = 17; p = 0.98), pond-dwelling black river turtles (R2 = 0.02; df = 6; p = 0.82), and pond-dwelling white-lipped mud turtles (R2 = 0.14; df = 7; p = 0.37). Similarly, no difference was found between the mean parasitemia of the black river turtles collected from the creek (0.35% ± 0.09) compared to the pond (0.29% ± 0.12) (Fig. 3B) (t = 0.39; df = 23; p = 0.70). The habitat use and movement patterns of black river turtles are poorly understood and it is possible that there were movements between the two sampled habitats.

In general, haemogregarines are considered to be of low pathogenicity for their vertebrate hosts (Brown et al., 1994, Knotkova et al., 2005), but some fitness effects have been noted in other reptiles (Oppliger et al., 1996). The lack of correlation between relative body mass and parasitemia suggests haemogregarines may not affect the health of these species of turtles, but additional research is needed to examine perhaps more subtle effects.

4. Conclusions

In summary, we detected ubiquitous infections of three turtle species with haemogregarines at two locations in Costa Rica. Although haemogregarines are not usually associated with clinical disease, baseline knowledge of the normal parasite fauna of these turtles is necessary to better understand disease threats that may emerge in the future as a result, for example, of habitat degradation. This is especially true for species of concern. Currently R. funerea is listed as near threatened and, although the statuses of K. leucostomum and K. scorpioides have not been evaluated, most turtles in Central America are in need of conservation (IUCN, 2012). Importantly, the ecology of these turtle species is not well understood, and future work on their behaviour and ecology may provide insights into the epidemiology of haemogregarines, as well as other potential conservation threats.

Acknowledgements

We thank the management of Selva Verde and La Pacifica for permission to work on their properties.

References

- Ball G.H. Some blood sporozoa from East African reptiles. J. Protozool. 1967;14:198–210. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.1967.tb01983.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barta J.R., Ogedengbe J.D., Martin D.S., Smith T.G. Phylogenetic position of the adeleorinid coccidia (Myzozoa, Apicomplexa, Coccidia, Eucoccidiorida, Adeleorina) inferred using 18S rDNA sequences. J. Eukaryot. Microbiol. 2012;59:171–180. doi: 10.1111/j.1550-7408.2011.00607.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown G.P., Brooks R.J., Siddall M.E., Desser S.S. Parasites and reproductive output in the snapping turtle, Chelydra serpentine, in southeastern Ontario. J. Parasitol. 1994;76:190–195. [Google Scholar]

- Cook C.A., Smit N.J., Davies A.J. A redescription of Haemogregarina fitzsimonsi Dias, 1953 and some comments on Haemogregarina parvula Dias, 1953 (Adeleorina: Haemogregarinidae) from southern African tortoises (Cryptodira: Testudinidae), with new host data and distribution records. Folia Parasitol. 2009;56:173–179. doi: 10.14411/fp.2009.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies A.J., Johnston M.R.L. The biology of some intraerythrocytic parasites of fishes, amphibia and reptiles. Adv. Parasitol. 2000;45:1–107. doi: 10.1016/s0065-308x(00)45003-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis A.K., Sterrett S.C. Prevalence of haemogregarine parasites in three freshwater turtle species in a population in Northeast Georgia. Int. J. Zool. Res. 2011;7:156–163. [Google Scholar]

- De Campos Brites V.L., Rantin F.T. The influence of agricultural and urban contamination on leech infestation of freshwater turtles, Phrynops geoffroanus, taken from two areas of the Uberabinha River. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2004;96:273–281. doi: 10.1023/b:emas.0000031733.98410.3c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ernst C.H., Ernst E.M. Ectoparasites associated with neotropical turtles of the genus Callopsis (Testudines, Emydidae, Batagurinae) Biotropica. 1977;9:139–142. [Google Scholar]

- Herban N.L., Yaeger R.G. Blood parasites of certain Louisiana reptiles and amphibians. Am. Midl. Nat. 1969;82:600–601. [Google Scholar]

- Hernandez-Divers S.M., Hernandez-Divers S.J., Wyneken J. Angiographic, anatomic, and clinical technique descriptions of a subcarapacial venipuncture site for chelonians. J. Herp. Med. Surg. 2002;12:32–37. [Google Scholar]

- IUCN, 2012. Rhinoclemmys funerea. IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. Version 2012.2. <http://www.iucnredlist.org> (Downloaded on 05 December 2012).

- Knotkova Z., Mazanek S., Hovorka M., Sloboda M., Knotek Z. Haematology and plasma chemistry of Bornean river turtles suffering from shell necrosis and haemogregarine parasites. Vet. Med. Czech. 2005;50:421–426. [Google Scholar]

- McAuliffe J.R. An hypothesis explaining variations of hemogregarine parasitemia in different aquatic turtle species. J. Parasitol. 1977;63:580–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCoy J.C., Failey E.L., Price S.J., Dorcas M.E. An assessment of leech parasitism on semi-aquatic turtles in the Western Piedmont of North Carolina. Southeast. Nat. 2007;6:191–202. [Google Scholar]

- Moll D., Jansen K.P. Evidence for a role in seed dispersal by two tropical herbivorous turtles. Biotropica. 1995;27:121–127. [Google Scholar]

- Morales-Verdeja S.A., Vogt R.C. Terrestrial movements in relation to aestivation and the annual reproductive cycle of Kinosternon leucostomum. Copeia. 1997;1997:123–130. [Google Scholar]

- Oppliger A., Célérier M.L., Clobert J. Physiological and behaviour changes in common lizards parasitized by haemogregarines. Parasitology. 1996;13:433–438. [Google Scholar]

- Readel A.M., Phillips C.A., Wetzel M.J. Leech parasitism in a turtle assemblage: effects of host and environmental characteristics. Copeia. 2008;1:227–233. [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute Inc. SAS Institute Inc.; Cary, NC: 2011. SAS/STAT 9.3 User’s Guide. [Google Scholar]

- Savage J.M. University of Chicago Press; Chicago: 2005. The Amphibians and Reptiles of Costa Rica: A Herpetofauna Between Two Continents, Between Two Seas. [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer R.T. Oxford University Press; Oxford, UK: 1986. Leech Biology and Behaviour. 1065pp. [Google Scholar]

- Siddall M.E., Desser S.S. Merogonic development of Haemogregarina balli (Apicomplexa, Adeleina, Haemogregarinidae) in the leech Placobdella ornata (Glossiphoniidae), its transmission to a chelonian intermediate host and phylogenetic implications. J. Parasitol. 1991;77:426–436. [Google Scholar]

- Siddall M.E., Desser S.S. Transmission of Haemogregarina balli from painted turtles to snapping turtles through the leech Placobdella ornata. J. Parasitol. 2001;87:1217–1218. doi: 10.1645/0022-3395(2001)087[1217:TOHBFP]2.0.CO;2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strohlein D.A., Christensen B.M. Haemogregarina sp. (Apicomplexa: Sporozoea) in aquatic turtles from Murphy’s pond, Kentucky. Trans. Am. Micro. Soc. 1984;103:98–101. [Google Scholar]

- Telford S.R. CRC Press; Boca Raton, London, and New York: 2009. Hemoparasites of the Reptilia: Color Atlas and Text. [Google Scholar]