Abstract

Background

Healthcare associated infections (HAI) have taken on a new dimension with outbreaks of increasingly resistant organisms becoming common. Protocol-based infection control practices in the intensive care unit (ICU) are extremely important. Moreover, baseline information of the incidence of HAI helps in planning-specific interventions at infection control.

Methods

This hospital-based observational study was carried out from Dec 2009 to May 2010 in the 10-bedded surgical intensive care unit of a tertiary care hospital. CDC HAI definitions were used to diagnose HAI.

Results

A total of 293 patients were admitted in the ICU. 204 of these were included in the study. 36 of these patients developed HAI with a frequency of 17.6%. The incidence rate (IR) of catheter-related blood stream infections (CRBSI) was 16/1000 Central Venous Catheter (CVC) days [95% C.I. 9–26]. Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTI) 9/1000 urinary catheter days [95% C.I. 4–18] and ventilator-associated pneumonias (VAP) 32/1000 ventilator days [95% confidence interval 22–45].

Conclusion

The HAI rates in our ICU are less than other hospitals in developing countries. The incidence of VAP is comparable to other studies. Institution of an independent formal infection control monitoring and surveillance team to monitor & undertake infection control practices is an inescapable need in service hospitals.

Keywords: Hospital acquired infections, ICU care, Infection control

Introduction

Health care-associated infections (HAI) are leading causes of morbidity and mortality among hospitalized patients.1 Five to 10% of patients admitted to acute care wards acquire one or more infections during their stay according to European prevalence surveys.2–5 This proportion is greater in immunocompromised patients and patients with underlying diseases, undergoing invasive procedures, admitted to an intensive care unit (ICU) and the elderly. In a multicentre study of tertiary care hospitals, HAI contributed to the death of 2.8% of patients that died 48 h after admission. Outbreaks of HAI are frequent and may spread between health care facilities (HCF) through patient transfers.6 Also HAI cause disability, reduce quality of life and create emotional stress.7

Effective infection control measures may prevent 20–30% HAI.8,9 Surveillance is a key element of the control and prevention of HAI because it provides data relevant for appropriate intervention methods.10 HAI has a growing social and political impact in today's day and age with burgeoning ageing populations because the elderly are more susceptible to infections and require increasingly intensive health care.11,12

HAI is defined as an infection which develops 48 h after hospital admission or within 48 h after being discharged that was not incubating at the time of admission at hospital.13 The risk of nosocomial infection in ICU is 5–10 times greater than those acquired in general medical and surgical wards.14 A likely explanation for this increased risk is that critically ill patients frequently require invasive medical devices such as urinary catheters, central venous and arterial catheters and endotracheal tubes thus compromising normal skin and mucosal barriers.

There is ample evidence from several countries that HAI are avoidable and costly to the health service and to patients.15 They are also a source of disability and distress to the individuals affected. Keeping these facts in mind the present study was designed to evaluate the prevalence of HAI in the ICU of a tertiary service hospital.

Aims

The aims of the study were:

To provide baseline information on the total incidence of HAI in the ICU of a tertiary service hospital and its burden in terms of increase in the length of stay. This information would be available to guide priority setting in the development of strategy and policy.

To develop a consistent methodology for incidence surveys which would represent a baseline to start from and would when repeated at intervals allow the impact of measures taken to reduce the burden of HAI to be evaluated through an analysis of trends.

Objectives

The objectives of the study were to answer the following questions.

What is the overall incidence of HAI and what are the specific types of HAI in adult inpatients in the surgical intensive care unit of a tertiary care service hospital?

What is the impact of HAI in terms of length of stay?

What are the priority areas for interventions to prevent and control HAI?

Furthermore, the objectives were:

To sensitize personnel to infection problems (e.g. micro-organisms, antibiotic resistance).

To provide relevant information to monitor and target infection control policies:

-

-

The compliance with existing guidelines and good practices,

-

-

The correction or improvement of specific practices,

-

-

The development, implementation and evaluation of new practices.

Patients and methods

This hospital-based observational study was conducted from December 2009 to May 2010 at a 10-bedded surgical intensive care unit (ICU) of a tertiary service hospital. Patients who were shifted out of the ICU within 48 h of admission were excluded from the study. All patients who were above 16 years of age, admitted in the surgical ICU with different complaints and presentations and developed clinical evidence of infection that did not originate from patient's original admitting diagnosis, were included in the study. These critical patients were referred for monitoring, observation and management from different departments, e.g., general surgery, neurosurgery, gynaecology/obstetric, reconstructive surgery, urology and accident/emergency departments. A proforma was designed and used for data collection. All data items were collected for all patients in the ICU, irrespective of their length of stay. Data for all patients who developed an infection was collected, irrespective of when the infection occurred. Infections studied were catheter-related blood stream infection (CRBSI), catheter-associated urinary tract infection (CAUTI), and ventilator-associated pneumonias (VAP).

Diagnosis of ICU acquired infections

For the purposes of surveillance, infections were diagnosed according to the HELICS infection definitions. This did not influence any aspect of clinical diagnosis and clinical decision-making.

HAI definitions

In this survey an HAI was an infection which arose ≥48 h or more after admission to hospital and which was not present or incubating on admission. A prevalent HAI was considered present when the patient had signs and symptoms which met one of the CDC definitions, or had one or more signs or symptoms included in one of the CDC definitions and was being treated for the infection (with therapy). CDC's HAI case definitions16 were adopted as these are widely used internationally. These definitions comprehensively categorize HAI according to the organ/tissue system affected.

A detailed history of patients was taken and thorough clinical examination was performed. Patients were examined on daily basis to assess the treatment response and to detect the evidence of development of any new infection. The temperature chart was also maintained and updated regularly. All the routine investigations such as complete blood picture, blood sugar level, urine analysis and chest radiograph were also done. The relevant investigations were performed according to the clinical presentation of patients and also after taking opinion from consultants of relevant departments. The frequency was assessed by number of patients who acquired infection; the pattern was determined by the type of acquired infection while aetiological agents were assessed by determining the pathogens or sources responsible for infection.

Results

Statistical analysis to calculate 95% confidence intervals for incidence of infections was done using EpiTable and chi square test for linear trend applied to length of stay and incidence of infection along with calculation of odds ratio was done using EPI Info software.

During our study period, total admissions to our ICU were 293. Patients admitted for more than 48 h were 204. 138 (67.64%) were males and 66 (32.35%) were females. Thirty Six (36) out of two hundred and four (204) patients were identified to acquire infection during their stay in the ICU. Thus the frequency of nosocomial infection was 17.64%. Demographic data of patients who acquired nosocomial infection are summarized in Table 1. Hospital acquired pneumonia was observed in 18 (50%) (Fig. 1) of the infected patients all of these had undergone or were on mechanical ventilatory support. The total number of days that all patients were ventilated amounted to 562.12 days. Thus it amounted to 32 infections per 1000 ventilator days [95% confidence interval 22–45] (Table 2). They developed signs of consolidation after 5–7 days and we categorized them as ventilator-associated pneumonia (VAP). The identified pathogens on broncho-alveolar lavage (BAL) in such patients were Acinetobacter sensitive only to imipenem and polymixin in 7 patients, Pseudomonas resistant to all antibiotics in one patient, Proteus in 2 patients and Klebsiella in 2 patients the other six patients did not grow any organism.

Table 1.

Demographic data of patients with nosocomial infection.

| Age (in yrs) | Number | % | Male n (%) | Female (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 16–29 | 8 | 22.2% | 25 (69.4%) | 11 (30.6%) |

| 30–39 | 6 | 16.67% | ||

| 40–49 | 8 | 22.2% | ||

| 50–59 | 6 | 16.67% | ||

| 60–69 | 5 | 13.89% | ||

| 70–79 | 3 | 8.33% | ||

| 80+ | ||||

| Total | 36 | 100% |

Fig. 1.

Pie chart showing the distribution of HAI based on the type of infection.

Table 2.

Common infections observed in ICU patients.

| Type of infection | Total no. & (%) | Infections per 1000 intervention days | 95% confidence interval |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pneumonia | 18 (50%) | 32/1000 vent days | (22–45) |

| Blood stream infection | 10 (27.77%) | 16/1000 catheter days | (9–26) |

| Urinary catheter infection | 8 (22.22%) | 9/1000 urinary catheter days | (4–18) |

| Total | 36 (100%) | 31/1000 days in ICU | |

| % of infection | 36/204 | 17.64% |

Blood stream infection was detected in 10 out of 36 (27.77%) (Fig. 1) infected patients. The source of such blood stream infections was central venous lines. The total number of days that all patients had indwelling Central Venous Catheters amounted to 627 days. Thus it amounted to 16 fresh infections per 1000 Central Venous Catheter days [95% C.I. 9–26] (Table 2).

Urinary tract infection was observed in 8 (22.22%) (Fig. 1) of the infected patients. Since all these patients were catheterized, Foley's catheter was considered as the source of infection. The total number of days that all patients had indwelling Foley's catheters was 955 days. Thus it amounted to 9 fresh infections per 1000 catheter days [95% C.I. 4–18] (Table 2). Only three were detected to be culture positive with Burkholderia cepacia, Escherichia coli & Pseudomonas aeruginosa grown in one patient each.

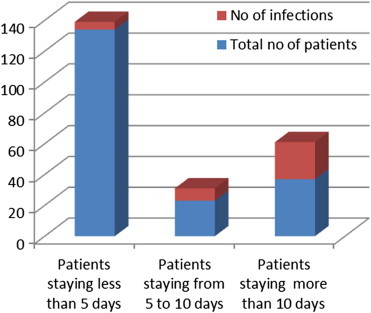

The total number of patients who stayed for less than 5 days in the ICU was 139 out of which 5 developed HAI. 26 patients stayed from 5 to 10 days out of which 7 developed HAI and of the 39 patients who stayed more than 10 days 24 developed HAI. This data was subjected to statistical analysis using chi square test for association between length of stay and the risk of developing HAI. Chi square value for linear trend was found to be 71.29, p value <0.001, odds ratio 1 for stay less than 5 days, 9.87 for stay between 5 and 10 days and 42.8 for stay beyond 10 days (Fig. 2). Thus proving that there is a highly significant risk of developing HAI as the length of stay in the ICU increased.

Fig. 2.

Bar chart showing length of stay (LOS) for all patients & infected patients based on the subspecialty.

Discussion

Critically ill patients in intensive care unit are at a higher risk of nosocomial infection due to multiple causes including disruption of barriers to infection by endotracheal intubation and tracheostomy, urinary bladder catheterization and central venous catheterization.17 The most common reported nosocomial infection in ICUs is urinary tract infection, followed by pneumonia and primary blood stream infection.18 The most common infection detected in our study was, however, ventilator-associated pneumonias (VAP) followed by catheter-associated blood stream infections (CRBSI) then catheter-related urinary tract infections (CAUTI). The frequency of nosocomial infection reported in the current study was 17.64% this is comparable to infection rates reported in other studies. In a relatively recent study by Rizvi et al, the frequency of nosocomial infection at two ICUs of a tertiary care hospital was 39.7%.19 The higher frequency of nosocomial infection in the latter study was attributed to the fact that a number of patients were on immunosuppressant drugs (Table 2).

CAUTI is the most common and frequent nosocomial infection seen in critically ill patients as reported in various studies.20,21 In our study only 8 (3.9%) patients were diagnosed to acquire urinary tract infection. The source of nosocomial UTIs was placement of Foley's catheter for a longer duration. Richards and colleagues reported in the National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System (NNIS) database that UTI was responsible for 20–30% of nosocomial infections in medical/surgical ICUs.18 Finkelstein and colleagues determined an incidence of 10–14% among 337 patients in a single Israeli ICU.22 The lower rates of CAUTI in our study were probably because most catheterizations were done by OT matrons or residents in the operation theatre under strict aseptic cover.

Nosocomial pneumonia is the second most frequent nosocomial infection in critically ill patients, and represents the leading cause of death from infection acquired in hospital.23 Over 90% of ICU acquired pneumonia develops during mechanical ventilation (VAP), and 50% cases of VAP occur in first 4 days after intubation.24 The predominant pathogens isolated in VAP are Pseudomonas aeruginosa, Staphylococcus aureus and Streptococcus pneumoniae.25

In our study of the 18 cases of VAP 12 were culture positive with one growing Pseudomonas aeruginosa, two growing Proteus mirabilis, two growing Klebsiella pneumoniae and a disturbingly high number of Acinetobacter at 7.

The frequency of VAP reported in different studies was 9%26, 18%27 and 21% (19). In our study, the frequency was 8.8% but this could be due to lesser number of more sick patients admitted to our ICU. The incidence rate (IR) reported in various studies per 1000 ventilated days ranges from 2.1 to 49.5 per 1000 ventilator days.28,29 The IR for VAP in our study was on the higher side at 32/1000 ventilator days.

Thus the relatively higher incidence of VAP in our study (32/1000 ventilator days) could probably be because of inadequate nursing manpower. Steps to further decrease the incidence have been instituted like: education of nursing staff regarding hand washing, suction protocols, meticulous change of ventilator tubing and HME as per protocols, propping up all patients in ICU, regular mouth care & hygiene.

Catheter-related blood stream infection is a common nosocomial infection acquired in the ICU, and in the USA, central venous catheterization is the cause of up to 28,000 deaths annually among patients in ICU's.30 Out of the ten cases of blood stream infections in our study, eight were culture positive with Pseudomonas aeruginosa accounting for six of them, Coagulase negative Staph aureus in one case, Burkholderia cepacia in two patients and E. coli in one patient. The incidence rate of blood stream infection in our study was 16/1000 catheter days. In the study by Rizvi et al,19 the frequency was 27%, probably because this study was conducted among critically ill patients admitted in nephrology and neurology intensive care units.

Our study showed an interesting finding as can be seen in the bar chart in Fig. 2 and Table 3 the average length of stay (LOS) in hospital was significantly higher for patients suffering from HAI as compared to the uninfected patients. Moreover, as can be seen from Table 3 and Fig. 3. The incidence of HAI also increased as the duration of stay in ICU increased (p < 0.001).

Table 3.

Showing the distribution of HAI based upon the number of days spent in ICU.

| Serial no | No. of patients | Patients staying less than 5 days | No of infections less than 5 days stay | Patients staying 5–10 days | No of infections 5–10 days stay | Patient staying more than 10 days | No of infections more than 10 days stay |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neuro | 96 | 67 | 2 | 10 | 3 | 19 | 7 |

| Onco | 30 | 24 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 6 | 5 |

| GI | 34 | 20 | 2 | 8 | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Gynae | 14 | 10 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Uro | 8 | 5 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Ortho | 4 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Vasc | 4 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Gen surg | 12 | 7 | 0 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| ENT | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| RSC | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

Fig. 3.

Component chart showing increased HAI in patients staying longer in the ICU.

Limitations of the study

The study was carried out over a period of 6 months to look at the incidence of HAI since the number of patients was small it is possible that the incidence rates may not be extremely accurate. However, with this small study a baseline level of information of HAI's in the service setting can be gathered.

Conclusion

From this observational study, we concluded that critically ill patients admitted to ICU are at a greater risk of acquiring nosocomial infection. HAI increases the length of stay in the ICU. Moreover, patients staying in ICU for a longer period of time are at a higher risk of acquiring HAI. The common nosocomial infections we identified in our study were nosocomial pneumonia including VAP, catheter-related urinary infections (CAUTIs) and blood stream infections.

The HAI rates in our tertiary care hospital ICU are marginally less than other hospitals in developing countries. The incidence of VAP is on the higher side as compared to other studies. Thus various interventions have been instituted. A similar study to assess the effectiveness of these interventions is being planned.

We recommend that efforts to increase the manpower situation, education and awareness among health care workers as well as adherence to standard guidelines for prevention of nosocomial infection should be used to reduce frequency of nosocomial infection in the intensive care unit.

Institution of an independent infection control monitoring and surveillance team to monitor & undertake infection control practices is now an inescapable need in the service hospitals.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Burke J.P. Infection control – a problem for patient safety. N Engl J Med. 2003;348(7):651–656. doi: 10.1056/NEJMhpr020557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lizioli A., Privitera G., Alliata E. Prevalence of nosocomial infections in Italy: result from the Lombardy survey in 2000. J Hosp Infect. 2003;54(2):141–148. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(03)00078-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lyytikainen O., Kanerva M., Agthe N., Möttonen T., Ruutu P., Finnish Prevalence Survey Study Group Healthcare-associated infections in Finnish acute care hospitals: a national prevalence survey, 2005. J Hosp Infect. 2008;69(3):288–294. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2008.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sax H., Pittet D., pour le comité de rédaction de Swiss-NOSO et le réseau SWISS-NOSO Surveillance Résultats de l'enquête nationale de prévalence des infections nosocomiales de 2004 (snip04) Swiss-NOSO. 2005;12(1):1–4. http://www.chuv.ch/swiss-noso/f121a1.htm [Article in French]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kaoutar B., Joly C., L'Heriteau F. Nosocomial infections and hospital mortality: a multicentre epidemiology study. J Hosp Infect. 2004;58(4):268–275. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2004.06.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Naas T., Coignard B., Carbonne A. VEB-1 extended-spectrum beta-lactamase-producing Acinetobacter baumannii, France. Emerg Infect Dis. 2006;12(8):1214–1222. doi: 10.3201/eid1208.051547. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Whitehouse J.D., Friedman N.D., Kirkland K.B., Richardson W.J., Sexton D.J. The impact of surgical-site infections following orthopedic surgery at a community hospital and a university hospital: adverse quality of life, excess length of stay, and extra cost. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002;23(4):183–189. doi: 10.1086/502033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Grundmann H., Barwolff S., Tami A. How many infections are caused by patient-to-patient transmission in intensive care units? Crit Care Med. 2005;33(5):946–951. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000163223.26234.56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Harbarth S., Sax H., Gastmeier P. The preventable proportion of nosocomial infections: an overview of published reports. J Hosp Infect. 2003;54(4):258–266. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(03)00150-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gastmeier P., Geffers C., Brandt C. Effectiveness of a nationwide nosocomial infection surveillance system for reducing nosocomial infections. J Hosp Infect. 2006;64(1):16–22. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2006.04.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Naiditch M. Patient organizations and public health. Eur J Public Health. 2007;17(6):543–545. doi: 10.1093/eurpub/ckm105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Farr B.M. Political versus epidemiological correctness. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2007;28(5):589–593. doi: 10.1086/515710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ferrer M., Valencia M., Torres A. Management of ventilator associated pneumonia. In: Vincent J.L., editor. 2008 Year Book of Intensive Care and Emergency Medicine. Verlag Berlin Heidelberg: Springer; 2008. pp. 353–364. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vincent J.L., Bihari D.J., Suter P.M. The prevalence of nosocomial infection in intensive care units in Europe. Results of the European prevalence of infection in intensive care (EPIC) study. EPIC International Advisory Committee. JAMA. 1995;274:639–644. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gastmeier P., Kampf G., Wischnewski N. Prevalence of nosocomial infections in representative German hospitals. J Hosp Infect. 1998;38(1):37–49. doi: 10.1016/s0195-6701(98)90173-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Atlanta: 1999. NNIS Manual. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Shannon S.C. Chronic critical illness. In: Jesse B.H., Gregory A.S., Lawrence D.H., editors. Principles of Critical Care. 3rd ed. McGraw Hill; 2005. pp. 207–215. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Richards M.J., Edwards J.R., Culver D.H., Gaynes R.P. Nosocomial infections in medical intensive care units in the United States. National Nosocomial Infections Surveillance System. Crit Care Med. 1999;27:887–892. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199905000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rizvi M.F., Hasan Y., Memon A.R. Pattern of nosocomial infection in two intensive care units of a tertiary care hospital in Karachi. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak. 2007;17:136–139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Laupland K.B., Zygun D.A., Davies H.D., Church D.L., Louie T.J., Doig C.J. Incidence and risk factors for acquiring nosocomial urinary tract infection in the critically ill. J Crit Care. 2002;17:50–57. doi: 10.1053/jcrc.2002.33029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Erbay H., Yalcin A.N., Serin S. Nosocomial infections in intensive care unit in a Turkish university hospital: a 2-year survey. Intensive Care Med. 2003;29:1482–1488. doi: 10.1007/s00134-003-1788-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Finkelstein R., Rabino G., Kassis I., Mahamid I. Device associated, device-day infection rates in an Israeli adult general intensive care unit. J Hosp Infect. 2000;44:200–205. doi: 10.1053/jhin.1999.0682. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jean Y.F., Jean C. Nosocomial pneumonia. In: Mitchell P.F., Edward A., Vincent J.L., Patrick M.K., editors. Text Book of Critical Care. 5th ed. Elsevier; 2005. pp. 663–677. [Google Scholar]

- 24.American Thoracic Society and Infectious Diseases Society of America Guidelines for the management of adults with hospital acquired, ventilator-associated and healthcare associated pneumonia. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2005;171:388–416. doi: 10.1164/rccm.200405-644ST. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chastre J., Wolff M., Fagon J.Y. Comparison of 8 vs. 15 days of antibiotic therapy for ventilator-associated pneumonia in adults: a randomized trial. JAMA. 2003;29:2558–2598. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.19.2588. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rello J., Ollendorf D.A., Oster G. Epidemiology and outcomes of ventilator-associated pneumonia in a large US database. Chest. 2002;122:2115–2121. doi: 10.1378/chest.122.6.2115. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cook D.J., Walter S.D., Cook R.J. Incidence of and risk factors for ventilator associated pneumonia in critically ill patients. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:433–440. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-129-6-199809150-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Edwards J.R., Peterson K.D., Andrus M.L., Dudeck M.A., Pollock D.A., Horan T.C. National Healthcare Safety Network (NHSN) report, data summary for 2006 through 2007. Am J Infect Control. 2008 Nov;36(9):609–626. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Rosenthal V.D., Maki D.G., Graves N. The International Nosocomial Infection Control Consortium (INICC): goals and objectives, description of surveillance methods, and operational activities. Am J Infect Control. 2008 Nov;36(9):e1–e12. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2008.06.003. (Review) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.O'Grady N.P., Alexander M., Dellinger E.P., Gerberding J.L., Heard S.O., Maki G.D. Guidelines for the prevention of intravascular catheter related infections. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 2002 Dec;23(12):759–769. doi: 10.1086/502007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]