Abstract

A structured discussion of End-of-Life (EOL) issues is a relatively new phenomenon in India. Personal beliefs, cultural and religious influences, peer, family and societal pressures affect EOL decisions. Indian law does not provide sanction to contentious issues such as do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders, living wills, and euthanasia. Finally, published data on EOL decisions in Indian ICUs is lacking. What is needed is a prospective determination of which patients will benefit from aggressive management and life-support. A consensus regarding the concept of Medical Futility is necessary to give impetus to further discussion on more advanced policies including ideas such as Managed Care to restrict unnecessary health care costs, euthanasia, the principle of withhold and/or withdraw, ethical and moral guidelines that would govern decisions regarding futile treatment, informed consent to EOL decisions and do-not-resuscitate orders. This review examines the above concepts as practiced worldwide and looks at some landmark judgments that have shaped current Indian policy, as well as raising talking points for possible legislative intervention in the field.

Keywords: End of life, Intensive care unit, Medical Futility, Do-not-Resuscitate Orders

Introduction

Consideration of End-of-Life (EOL) issues is a relatively new phenomenon in the Indian context. This assumes great importance in Intensive Care Units (ICUs), where the mortality figures account for 10–36% of the total deaths in an institution.1 While critical management is usually aggressive, a debate regarding continuation of life-support arises in a subset of critically ill patients, where it may be obvious (as per the existing evidence on the disease's severity and reversibility) that the chances of meaningful survival and/or return to an economically viable life are limited.

Intensive care resource allocation is both expensive and limited (<1 hospital bed/1000 people and an even lower number of ICU beds in India). Consequently, the concept of “Managed Care” is emerging worldwide based on the notion that unnecessary Health-care costs can be reduced through a variety of mechanisms, including programs for reviewing the medical necessity of specific services, economic incentives for physicians and patients to select less costly forms of care; and controls on inpatient admissions and lengths of stay.2 In countries such as Argentina, Mexico and USA, this is being enforced by laws such as the US Health Maintenance Act of 1973. In countries such as India where ∼80% of the total health care bill is paid by the patient or their relatives, the concept is informal. In countries such as UK, Canada, Germany and Australia, where health care is largely government-funded, Managed Care is restricted to financial auditing only. Entitled patients in the Armed Forces Medical Services (AFMS) hospitals have access to unlimited government-funded medical care.

Legal provisions too should be kept in sharp focus while dealing with issues of life-support, life sustenance and termination of care. In India, the Fundamental Right to Life (Article 21 of the Constitution of India) limits the role of patients/next-of-kin (NOK, which includes spouse, parents or any other legally appointed surrogate) in EOL decisions. Practices such as euthanasia and Physician-Assisted Suicide (PAS) are not followed as they violate the Indian Penal Code, 1860 (IPC).3 Autonomy (see below) is not legally sanctioned and so, a physician is not obliged to accept choices made by a patient which are deemed self-destructive. Patient and family choices are framed, and in cases limited, by physician beliefs regarding what is appropriate, and where the law and social norms are not clear, what is allowed.1

Magnitude of problem

Western data shows that termination of medical treatments is currently the norm. In Australia, 72.6% deaths are preceded by limitation of treatment. Withholding of therapy is reported in 38% of patients and withdrawal of treatment in 33% in European ICUs, although there were considerable variations according to country. More than 85% of Americans die without cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), and ∼90% of decedents in American ICUs have withholding or withdrawal of medical treatments, with an average of 2.6 interventions being withheld or withdrawn per decedent. As per the British Medical Association, the Resuscitation Council (UK), and the Royal College of Nursing Joint Study, do-not-resuscitate (DNR) orders are more commonly used for older people, colored people, alcohol misusers, non-English speakers and people infected with human immunodeficiency virus—suggesting that doctors do have stereotypes of who is not worth saving.3,4

There is a paucity of data on EOL decisions in Indian ICUs. Only two studies1,5 have been performed. A uni-centric survey on the practices of EOL decision-making in North India noted that 78% patients received full resuscitation; in the 22% who were classified as receiving limitation of care, 18.8% were transferred out of ICU terminally for financial or other reasons. Only 1.6% of ICU deaths had DNR orders. Life-support was withheld in another 1.6%.1

A second study revealed that 34% of deaths in Mumbai had terminal limitation of therapy. 25% patients were not intubated; 67% were initially intubated and ventilated but had no further escalation of therapy and 8% had withdrawal of therapy.5 These studies are limited because, in India, approaches such as DNR orders, living will, euthanasia and advance directives are not legally acceptable. Doctors are reluctant to reveal individual EOL practices for fear of punitive action. Life-support systems are rarely withdrawn; though not starting therapies tends to be more acceptable. These decisions, when made, are usually based on institutional policies for want of a uniform Governmental policy as existing in the West.1,6

Additionally, from the patient's point of view, a host of uncontrolled factors have effects on EOL issues including personal beliefs, cultural and religious influences, peer and family pressure. Indian cultural values are reflected in the practices of advance care planning, informed consent, individual decision-making and candid communication of the patient's condition. The average Indian has great respect for learning and the learned, which includes the doctors. Secondly, they are guided by familism, particularly respect for elders and ancestors. Finally, they prefer to avoid conflicts. These three values have a profound influence in their approach towards EOL decisions. Terminally ill patients and/or their families may themselves prefer to take the patient home, to perform socially pertinent rituals or due to the exorbitant cost of critical care in most civilian institutions.6,7

Concept of euthanasia and medical futility

Euthanasia (Greek ‘Eu’ = good; ‘thanatos’ = death), by definition, is an intentional killing of a person whose life is perceived to be not worth living by an act of commission or omission. Active euthanasia is an act of commission when termination of life is done at the patient's request. If the means whereby a patient can end his/her life is supplied by a doctor, it is termed assisted suicide. Medical futility (MF) implies pointlessness of continued care and is an act of omission under directives of a doctor. Schneiderman and colleagues described MF as “quantitatively futile when it is shown to be useless in the last 100 cases in which it has been tried and qualitatively futile when it would result in nothing better than permanent unconsciousness or persistent dependence on intensive care”.8 However, most cases are too complex and nuanced to be resolved by such blunt definitions.9

Futility is a professional judgment that permits doctors to withhold/withdraw care deemed inappropriate without subjecting such a decision to patient/NOK approval. Two major determinants of MF are length of life and quality of life. In resuscitation a qualitative definition of futility must include low chance of survival and low quality of life afterward. Key factors are the underlying disease before cardiac arrest and expected state of health after resuscitation. Qualitative futility implies the possibility of hidden-value judgments. Treatments should be defined as futile only when the intended goal will, in all probabilities, not be accomplished.10 In the face of inevitable death, allowing a patient to die by forgoing or withdrawing failed/futile treatment is not euthanasia; unfortunately, MF is sometimes referred to as passive euthanasia.

The Consensus Statement of the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine's (ISCCM) Ethics Committee regarding guidelines for limiting life-prolonging interventions and providing palliative EOL care (itself based on American College of Critical Care Medicine recommendations11) is given in Table 1.12 Each situation should be evaluated on a case-by-case basis and careful procedural safeguards should be in place to assure that futility determinations are just and fair.

Table 1.

Consensus Statement of the Indian Society of Critical Care Medicine's Ethics Committee regarding futile treatment in Indian Intensive Care Units.

| 1. The physician has a moral obligation to inform the capable patient/family, with honesty and clarity, the poor prognostic status of the patient when further aggressive support appears non-beneficial. The physician is expected to initiate discussions on the treatment options available including the option of no specific treatment. 2. When the fully informed capable patient/family desires to consider comfort care, the physician should explicitly communicate the available modalities of limiting life-prolonging interventions. If the patient or family do not desire the continuation of life-supporting interventions the available options for limiting the supports should be identified as follows: (i) withdrawal of life-support (ii) withholding of life-support and (iii) do-not-resuscitate status. 3. The physician must discuss the implications of forgoing aggressive interventions through formal counseling sessions with the capable patient/family, and work toward a shared decision-making process. Thus, he accepts patient's autonomy in making an informed choice of therapy, while he fulfills his obligation of providing beneficent care. 4. Pending consensus decisions or in the event of conflicts between the physician's approach and the family's wishes, all existing supportive interventions should continue. The physician however, is not morally obliged to institute new therapies against his better clinical judgment. 5. The proceedings of the counseling sessions, the decision-making process, and the final decision should be clearly documented in the case records, to ensure transparency and to avoid future misunderstandings. 6. The overall responsibility for the decision rests with the attending physician/intensivist of the patient, who must ensure that all members of the caregiver team including the medical and nursing staff represent the same approach to the care of the patient. 7. If the capable patient/family consistently desires that life-support be withdrawn, in situations in which the physician considers aggressive treatment non-beneficial, the treating team is ethically bound to consider withdrawal within the limits of existing laws. 8. In the event of withdrawal or withholding of support, it is the physician's obligation to provide compassionate and effective palliative care to the patient as well as attend to the emotional needs of the family. |

In India, a debate on euthanasia was kick-started after 25-year-old Kolavennu Venkatesh pleaded that doctors be allowed to harvest his organs for transplantation so that other lives would be saved. He suffered from muscular dystrophy and was aware that he would soon die. Since there was a grave risk that in his enfeebled state, widespread infection could occur that would make transplantation of organs impossible, he and his mother, K Sujatha pleaded that his organs be harvested by terminating his life. Unfortunately, he died two days after the Andhra Pradesh High Court rejected his plea for euthanasia. Apart from his eyes, Venkatesh left behind a debate on the ethical and legal aspects of euthanasia.13,14

Withholding or withdrawal

Withholding or withdrawal of life-sustaining treatments in the ICU typically occurs in two situations: when prognosis for survival with/without treatment is poor, or when potential benefits of treatment, in terms of quantity and quality of life, are not, in the judgment of the patient or the surrogate decision-maker (not the doctor!), worth the financial (and emotional) burden.15

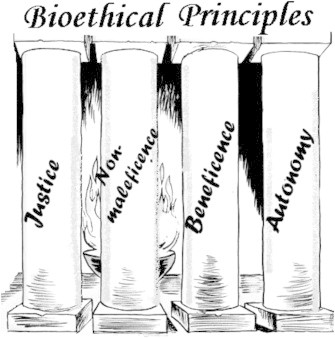

All ethical codes applicable to doctors including the International Code of Medical Ethics and the Hippocratic Oath are based on what is referred to as “Humanist Philosophy”.16 These share along with the Bioethical Principle of Beneficence, the concept that a doctor is expected to alleviate pain and suffering of patients on one hand, and to protect and prolong lives on the other.17 Even the Bioethical Principle of Justice, (“similar patients should receive similar care”, forming the basis of Principles of Triage), lay down guidelines for allocation of health care resources. These two Principles form part of the “Four Pillars” of Bioethics, the other two being the Principle of Autonomy (see later) and Principle of Nonmaleficence (“do no harm”) (Fig. 1). However, conventional thinking on Bioethical issues does not justify termination of life-sustaining care, merely on the plea that the resources could be better employed elsewhere. Doctors, even with legal sanction, typically withhold/withdraw only life-sustaining measures such as CPR, life-saving surgery, intrusive palliative procedures, balloon pumps, ventilators, dialysis, pacemakers, vasopressors, blood, antibiotics and insulin. Parenteral and enteral fluids or nutrition are usually not withheld/withdrawn.18,19

Fig. 1.

Four cardinal pillars of bioethical principles: justice (similar patients should receive similar care), nonmaleficence (do no harm), beneficence and autonomy (see text). (Taken with permission from Beauchamp, Tom; Childress James. Principles of Biomedical Ethics, Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press; 2001, ISBN 0-19-514332-9.)

No legal directives are available the world over for those situations when financial implications assume importance to the patient/family. The consensus statement provided by the American College of Chest Physicians/SCCM Consensus Panel on Ethical and Moral Guidelines specifies that “A patient's productivity or economic value must play no role in the decision whether to undertake or withdraw intensive care”.11 If a competent, informed patient asks that support be withdrawn because it is economically burdensome, patient's autonomy should take precedence over the physician's concept of what is beneficial for the patient. However, the treating doctor has an obligation to ameliorate the patient's financial concerns by all means possible, including waiving of fees and involving other members of the health care team to help resolve the perceived problem.11,20 When the patient is incompetent and NOK expresses financial concerns, the physician's obligation becomes to ensure that there is no conflict of interest between NOK's economic concerns and patient's benefit before withdrawing support.

Advanced directives and do-not-resuscitate orders

Another paradigm shift is the increasing legal acceptance of the Bioethical Principle of Autonomy which focuses on the limit to which a patient can exercise his right to decide what is to become of his/her body. With autonomy being practiced through the Doctrine of Informed Consent, a competent individual can give advance consent as well as express advance refusal to treatment of any nature for a subsequent period of decisional incapacity. Such documents signed by the patient are called Advance Directives (ADs). USA has legalized this by the Patient Self Determination Act (1990) and the Uniform Rights of the Terminally Ill Act (1985, revised 1989). European countries have similar laws also (e.g., Mental Capacity Act, 2005, UK). ADs can be for specific refusal of life-support if terminally ill or in coma (“Living Will”) or can be for nominating spouse, relative or other person entrusted to make medical decisions when he/she would be unable to do so (“Durable Power of Attorney for Health Care”).1,4,15,21

ADs are legally binding for a clinician if the patient is incapacitated or unconscious, irrespective of the outcome. Doctors can and have been penalized for institution of life-saving treatment as it amounts to interference with the patient's bodily integrity.

A specialized documented AD is the Do-Not-Resuscitate (DNR) Directives which are a well documented and accepted concept in most developed countries. It originated with American Society of Anaesthesiologists Guidelines (1993) for DNR directives for cardiac arrest under anesthesia in the operating room only where the chance of survival in “witnessed arrests” is high. These evolved into the Limited Aggressive Therapy Order (LATO) (2003) in the US in which the range of where the range of “higher-success” situations was increased to include witnessed cardiopulmonary arrest where the initial cardiac rhythm is ventricular tachycardia or fibrillation and cardiac arrest resulting from a readily identifiable iatrogenic cause.22

ADs including DNR and LATO have no legal sanction in India.3 Therefore, doctors may be held to have violated the law should they issue even unwritten, verbal DNR recommendations to the patient's caregiver or relative for terminally ill or patients with poor prognosis. Many hospitals are now adopting local futility policies based upon ISCCM ICU guidelines. However, similar guidelines by any national reputed clinical body are lacking in an operating room set-up.1,15,19

Implications to Human Organ Transplantation Act (HOTA) (1994)

Under HOTA, human organs can be legally removed from the body of a person pronounced brain-dead by a board of medical experts constituted in accordance with the provisions of the Act. The valid consent for the same should have been given by the person during his lifetime or by the NOK if person is less than 18 years of age.23 There are a few ambiguities in HOTA. HOTA is silent on stopping life-support treatment in a certified brain-dead individual if consent for organ harvesting is not forthcoming. That would account as euthanasia and is punishable.

‘Non-Heart-Beat Donors’ (NHBD) do not fall under the purview of the Act. In these donors, a person is declared dead by cardiopulmonary criteria after establishing that circulation and respiration have permanently ceased. This by itself raises a number of ethical issues. Postmortem invasive procedures to minimize organ damage (interventions such as putting the dead on ventilation and cardiopulmonary bypass, or in-situ preservation) without the consent of NOK might amount to assault to the “property” of NOK. Also, the act can be construed as indignity if done with intention (under section 297 IPC). Similarly the deceased's relative may file a claim for mental trauma, particularly if the interference has been witnessed.

Consensus is also lacking on the time before any intervention geared towards organ retrieval is attempted (heparin to prevent intravascular clotting and phentolamine to maintain vascular perfusion) as these cannot be considered as beneficial to the patient. The Maastricht Workshop considered that a period of 10 min without brain perfusion was necessary before starting any intervention toward organ retrieval. The Institute of Medicine recommends a 5-min observation period. The Pittsburgh Protocol sanctions surgical retrieval of organs at 2 min after asystole.24,25

Legal aspects of End of Life issues in India

The Constitution of India not only guarantees the right to live but also provides directives to the State to provide health care to all citizens. This is illustrated in the following provisions:

-

•

Article 21 – Protection of life and personal liberty: No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedure established by law.

-

•

Article 14 – Equality before law: The state shall not deny to any person equality before the law or equal protection of the laws within the territory of India.

-

•

Articles 39 and 47 of the Directive Principles of State Policy.

The Supreme Court of India in its landmark judgment in Pt Parmanand Katara vs. Union of India and others (AIR 1989, SC 2039), ruled that every doctor whether at a Government hospital or otherwise has the professional obligation to extend his services with due expertise for protecting life. Not only is every citizen given a constitutional guarantee to live, the medical profession is also charged with the responsibility to protect the life of all citizens by providing medical attention.

A physician who practices euthanasia would be charged under Sec 299 or Sec 304 A, IPC, depending on the method used as the intent to kill qualifies euthanasia as a crime. All people including relatives who participated or were aware of such intent on the part of the physician could be charged under Sec 107 and 202 IPC and in cases where the entire process is undertaken at their behest, relatives could be charged under Sec 299 or 304 IPC as well. A physician might cite the provisions of Sec 87, Sec 88 and Sec 92, IPC to defend himself in cases where he is alleged to have used terminal sedation for an act of mercy killing. Intent will become a material consideration in such a case.1,3,20

The distinction between suicide and euthanasia has been elucidated in the case of Naresh Marotrao Sakhre vs. Union of India (1994) where it has been held that, “Euthanasia or mercy killing is nothing but homicide whatever the circumstances in which it is effected.”

A Constitution Bench of the Supreme Court in Gian Kaur vs. the State of Punjab, (1996) 2 SCC 648 ruled that permitting termination of life in the dying or vegetative state is not compatible with Article 21 stating, “The court clearly mentioned in this case that Article 21 only guarantees right to life and personal liberty and in no case can the right to die be included in it.”26

Future directives

There is a felt need to review the legal position in situations where medical futility is certain. In India, the law regarding EOL issues is predominantly silent and relatively archaic at places with a paucity of case laws on this subject. On 07 Mar 2011, the Supreme Court (Aruna Shanbaug vs. Union of India and others) took a tentative step in this direction. As per this landmark judgement, the decision for withdrawal of life support of a patient in a ‘permanent vegetative state’ can be taken only by the NOK (specified by the Court as parents or the spouse or other close relatives, or in the absence of any of them, a person or a body of persons acting as a ‘next friend’) or the attending doctor with the caveat that the decision should be taken bonafide in the best interest of the patient. These guidelines will be the law until Parliament enacts a legislation on the subject. Briefly, an application is to be filed to the Chief Justice of the High Court who will constitute a bench of at least two judges to decide on the issue. Before doing so they will consult a panel of at least three experts, consisting of a neurologist, psychiatrist and a physician as recommended by the State, who will examine the patient and submit their report to the Court. Simultaneously, notice will be issued to the State, near relations or in their absence, close friends. The views of the near relatives and committee of doctors would be given due weight by the High Court before pronouncing a final verdict which shall not be summary in nature.

To formulate uniform national guidelines, it is imperative to have a multitude of deliberations at all levels as which took place in the developed world which ultimately lead to legislative adoption of certain EOL policies. These deliberations should have legal experts and representatives of the Health Ministry, NGOs and Human Right Activists and religious leaders. It would help to have terminally sick individuals also on board. An initial prerequisite is an acceptable legal definition of ‘medical futility’ as well as elucidation of brain death and clinical death.

AFMS and EOL issues

AFMS being the largest medical body in the country needs to take an initiative towards this end. A general AFMS protocol can be formulated for withdrawal of active treatment in special circumstances on lines of the Aruna Shanbaug case with an absolute prohibition on active euthanasia. Distinction should be made between withholding and withdrawing treatments, between consequences that are intended vs. those that are merely foreseen (Doctrine of Double Effect).27 EOL care continues even after the death of the patient, and AFMS ICUs should consider developing comprehensive bereavement programs to support both families and the needs of the clinical staff.

Conclusions

A structured discussion of EOL issues is a relatively new phenomenon in India. There is also a need for emphasis on education in bioethics starting from the undergraduate levels.

Until then, in the current legal scenario, while dealing with EOL issues, effective communication remains the key. Talks should be “bilateral”, addressing overtreatment by both clinicians and families. There must be clear documentation of efforts to achieve resolution with the patient and family, emphasizing that limiting the use of life-sustaining treatments will not lead to abandonment. Only if repeated efforts fail, should the case be referred to the institutional Ethics Advisory Committee.

Similarly, if the withdrawal of active treatment is being considered for harvesting organs or as a medical futility, it should be mandatory that the decision should be communicated to the family by the clinician and should be documented in the clinical notes. Organ transplant team should not be involved in any decision to withdraw treatment. This ensures that the interest of the dying patient remains paramount. Additionally, there is a pressing need for hospice services in India. These measures are essential to give death a dignity.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have none to declare.

References

- 1.Mani R.K. Limitation of life support in the ICU: ethical issues relating to end of life care. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2003;7:112–117. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cooper C.C., Gottlieb M.C. Ethical issues with managed care: challenges facing counseling psychology. Couns Psychol. 2000;28:179–236. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rudra A. Euthanasia and physician assisted suicide. In: Dogra T.D., Rudra A., editors. Lyons Medical Jurisprudence & Toxicology. 11th ed. Delhi Law House; 2005. pp. 236–243. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Prendergast T.J., Claessens M.T., Luce J.M. A national survey of end-of-life care for critically ill patients. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1998;158:1163–1167. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.158.4.9801108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sprung C.L., Cohen S.L., Sjokvist P. End-of-life practices in European intensive care units: the Ethicus Study. JAMA. 2003;290:790–797. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.6.790. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kapadia F., Singh M., Divatia J. Limitation and withdrawal of intensive therapy at the end of life: practices in intensive care units in Mumbai, India. Crit Care Med. 2005;33:1272–1275. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000165557.02879.29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Barnett V.T., Aurora V.K. Physician beliefs and practice regarding end-of-life care in India. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2008;121(3):109–115. doi: 10.4103/0972-5229.43679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Carey S.M., Cosgrove J.F. Cultural issues surrounding end-of-life care. Curr Anaesth Crit Care. 2006;17:263–270. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schneiderman L.J., Jecker N.S., Jonsen A.R. Medical futility: its meaning and ethical implications. Ann Intern Med. 1990;112:949–954. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-112-12-949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Helft P.R., Siegler M., Lantos J. The rise and fall of the futility movement. N Engl J Med. 2000;343:293–296. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200007273430411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mohindera R.K. Medical futility: a conceptual model. J Med Ethics. 2007;33:71–75. doi: 10.1136/jme.2006.016121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ethical and moral guidelines for the initiation, continuation, and withdrawal of intensive care: American College of Chest Physicians/Society of Critical Care Medicine Consensus Panel. Chest. 1990;97(4):949–958. doi: 10.1378/chest.97.4.949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mani R.K., Amin P., Chawla R. ISCCM position statement: limiting life-prolonging interventions and providing palliative care towards the end of life in Indian intensive care units. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2005;9:96–107. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bansal R.K., Das S., Dayal P. Death wish. JK Sci J Med Educ Res. 2005;7(3):169–171. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Venkatesh is Gone, But His Struggle Lives. The Times of India. Dec 18, 2004.

- 16.Puri V.K. End-of-life issues for a modern India – lessons learnt in the West. Indian J Crit Care Med. 2005;9:81–85. [Google Scholar]

- 17.International code of medical ethics of the World Medical Association. World Med Assoc Bull. 1949;1(3):109–111. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Fraenkel L., Fried T.R. Individualized medical decision making: necessary, achievable, but not yet attainable. Arch Intern Med. 2010;170:566–569. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2010.8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mack J.W., Weeks J.C., Wright A.A., Block S.D., Prigerson H.G. End-of-life discussions, goal attainment, and distress at the end of life: predictors and outcomes of receipt of care consistent with preferences. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:1203–1208. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.25.4672. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mani R.K., Mandal A.K., Bal S. End-of-life decisions in an Indian intensive care unit. Intensive Care Med. 2009;35(10):1713–1719. doi: 10.1007/s00134-009-1561-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Troug R.D., Campbell M.L., Curtis J.R. Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit: a consensus statement by the American College [corrected] of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008;36(3):953–963. doi: 10.1097/CCM.0B013E3181659096. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jeong S.Y., Higgins I., McMillan M. The essentials of advance care planning for end-of-life care for older people. J Clin Nurs. 2010 Feb;19(3–4):389–397. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2009.03001.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choudhry N.K., Choudary S., Singer P.A. CPR for patients labeled DNR: the role of the limited aggressive therapy order. Ann Intern Med. 2003;138(1):65–68. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-138-1-200301070-00014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ministry of Law. Justice and Company Affairs. Government of India . Government of India; New Delhi: 1994. The Transplantation of Human Organs Act 1994 No.42 of 1994.http://india.gov.in/allimpfrms/allacts/2606.pdf [Internet] [cited 2010 Mar 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bardale R. Issues related with non-heart-beating organ donation. Indian J Med Ethics. 2010;7(2):104–106. doi: 10.20529/IJME.2010.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Doig C.J., Rocker G. Retrieving organs from non-heart-beating organ donors: a review of medical and ethical issues. Can J Anaesth. 2003;50:1069–1076. doi: 10.1007/BF03018376. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Court Ruling, Aruna Shanbaug vs. Union of India, March 7, 2011 at Supreme Court of India.