Abstract

Although, urethral injuries are relatively uncommon, their incidence has been increasing due to increasing incidence of road traffic accidents. Initial management of urethral injury depends upon the degree and location of the injury, patients' haemodynamic status, and any associated injuries. Besides these factors, availability of clinical infrastructure and clinical expertise also play a significant role in making appropriate management decisions at the time of injury.

Key Words: haematuria, pelvic injury, urethral disruption, urethral injury, urethral stricture, urethral trauma

Introduction

Urethral injuries have conventionally been reported to be uncommon. However, with increasing incidence of road traffic accidents, their incidence is also increasing. Majority of urethral injuries result from either blunt trauma (usually associated with a pelvic fracture) to abdomen or straddle injury to pelvis. Other rarer causes of urethral injuries include penetrating injuries and gunshot injuries. Urethral injuries from pelvic fracture are typically associated with multiple organ injuries (bladder, spleen, liver, and bowel) and high mortality rates.1,2

Urethral injuries may also lead to debilitating complications like urethral stricture, urinary incontinence, and impotence. A prompt diagnosis and grading of the injury, along with an appropriate intervention strategy is required to avoid such debilitating complications. However, expertise and resources to manage such cases are limited and not readily available in India and hence, the management strategy has to be tailored to obtain the best possible outcome. We present an overview of the approach to management of urethral injuries for general surgeons in semi-urban and rural settings.

Posterior Urethral Injuries

Posterior urethral injuries are usually associated with pelvic fracture and are detected in up to 10% of male and 6% of female patients sustaining pelvic fractures. Posterior urethral injuries are caused by shearing forces at points of fixation, which leads to prostate-membranous junction disruption. However, ‘bulbo-membranous junction avulsion’ can be an alternative mechanism for such injuries.2–5

Signs and Symptoms

The classical triad of posterior urethral injury in males includes:

-

•

Blood at the urethral meatus.

-

•

Inability to void (or distended bladder).

-

•

Pelvic fracture with pelvic haematoma.

But, there are exceptions to this. For example, patient may be able to pass urine if there is partial disruption of urethra. Other signs of urethral injury include:

-

•

Gross haematuria.

-

•

Scrotal, perineal, or penile haematoma.

-

•

Difficulty in passing Foley's catheter.

-

•

‘High riding’ or non-palpable prostate (usually unreliable).6

Amongst these signs, the presence of blood at the urethral meatus is the most important and demands a thorough evaluation to identify its origin.

Signs of urethral injury in females include:

-

•

Vaginal bleeding or laceration (80%).

-

•

Urethral bleeding.

-

•

Haematuria.

-

•

Labial swelling.

-

•

Inability to void.7

Grading

A proper and accurate grading of urethral injury is essential for planning management of urethral injuries. Urethral injuries can be graded by retrograde urethrography or flexible cystoscopy.7 Cystoscopy may be the preferred choice as it can also offer definitive treatment.

The two urethral injury scales commonly employed for grading of urethral injuries are:

-

1.Colapinto and McCallum grading. Colapinto and McCallum grading emphasises on the location of the injury in relation to the urogenital diaphragm. The original system described three types of urethral injuries.8

-

•Type I—Urethral stretch injury

-

•Type II—Urethral disruption proximal to genitourinary diaphragm

-

•Type III—Urethral disruption both proximal and distal to urogenital diaphragm.

Goldman et al later revised this classification and added two more types of urethral injuries.9

-

•

-

•

Type IV—Bladder base injuries

-

•

Type V—Straddle anterior urethral injuries.

-

2.The American Association for Surgery and Trauma (AAST) grading: The AAST grading emphasises the degree of disruption and the degree of urethral separation.10 It divides urethral injuries into the following five types:

-

•Type I—Contusion

-

•Type II—Stretch injury but no disruption of urethra

-

•Type III—Partial disruption of urethra

-

•Type IV—Complete disruption with urethral separation < 2 cm

-

•Type V—Complete disruption with urethral separation > 2 cm.

-

•

Types I and II injuries together constitute about 25% of cases, type III injuries account for another 25% of cases and the remaining 50% are types IV and V injuries (as per the AAST grading).3

Management

Goals of Treatment

-

•

Stabilise the patient's haemodynamic status and replace blood in case of massive blood loss.

-

•

Identify associated injuries and properly triage the patient.

-

•

Confirm the diagnosis of urethral injury and seek expert advice wherever needed.

Integrated Management Approach

The management of injuries to the head, thorax, and abdomen must always take precedence over any suspected urethral injury. It is vital to see the patient and his/her injuries in totality and pay due attention to any associated head/chest/limb injuries, which at times might prove to be life/limb saving.

For urethral injury, the aim of treatment is to re-establish urethral continuity while minimising chances of infecting pelvic haematoma and reducing risk of urethral stricture, incontinence and impotence. However, the ideal method as well as the timing of repair is controversial.

The definitive management of urethral injury may be:

-

•

Immediate primary treatment—within 48 hours of injury

-

•

Delayed primary treatment—2–14 days of injury

-

•

Deferred treatment—three months or more after the injury.

Due to lack of proper expertise and resources, majority of the patient in suburban India undergo delayed primary or deferred treatment.

Immediate Treatment

In any patient with suspected urethral injury, traditionally catheterisation has been avoided to prevent converting a partial tear into complete urethral injury and infecting the haematoma.1,11 However, due to relative lack of evidence of conversion of partial tear into complete rupture of urethra, and shortage of trained surgeons to carry out urethral repair in emergency settings, we recommend one gentle attempt to Foley's catheterisation. Shlamovitz and McCullough, in their study found that attempts at blind catheterisation in patients with suspected urethra injury did not increase the severity of the urethral injury, further supporting gentle trial for catheterisation in such patients.12 The urethra should be adequately anaesthetised while attempting catheterisation, in order to relax the sphincter. In patients, where Foley's catheterisation is successful, the catheter should be left in situ for at least 4–5 weeks. If the patient develops a urethral stricture, it is treated at a later date. A similar policy should be adopted for patients who are referred with a urethral catheter already in place and have a suspected urethral injury. Our recommended approach for managing posterior urethral injury is depicted in Algorithm 1.

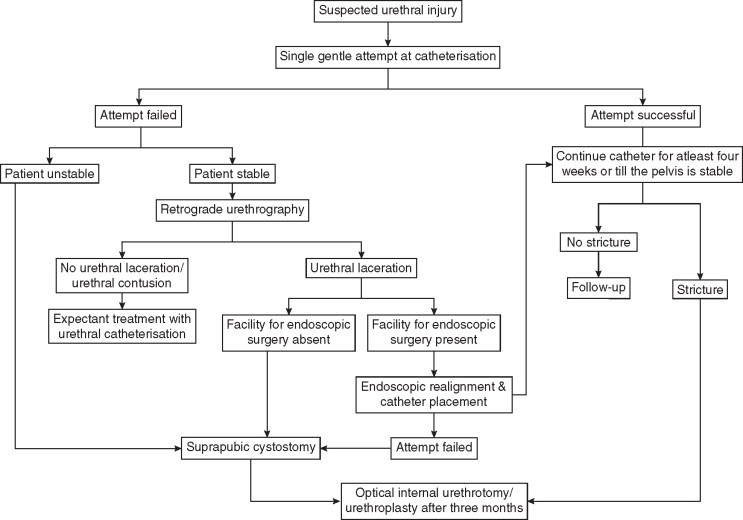

Algorithm 1.

Approach to management of posterior urethral injury.

Immediate primary open surgical repair of urethral injury is not recommended as it is technically difficult, is associated with a higher incidence of postoperative incontinence and impotence and potential release of pelvic haematoma tamponade effect leading to uncontrolled bleeding. In patients undergoing open surgery for concomitant bladder neck or rectal injuries, or other associated abdominal injuries, open urethral realignment by simply passing a catheter across the defect can be considered. However, this policy is still associated with urethral strictures in up to 50–100% of the patients.13,14

In cases, where it is not possible to negotiate the Foley's catheter, retrograde urethrogram is done for the further evaluation and staging of the injury. Endoscopic primary realignment using flexible cystoscope and guidewire is the first line of management for haemodynamically stable patients. Urethra can be realigned using either one cystoscope and guidewire to place the catheter or using two cystoscopes, one from the urethra side and the other from the bladder side, to aid catheter placement across disruption using the Seldinger technique.15 The catheter should then be left in situ for at least 4–6 weeks, over which the distracted urethral ends come together to aid healing.

Immediate endoscopic repair for posterior urethral injuries has been recommended as the standard of care by some Indian authors. However, they also appreciate that this approach can be used as the standard practice only in urban centres that have round the clock facilities of such treatment.16

Urethral realignment may be deferred in haemodynamically unstable patients by up to two weeks and attention given to more alarming life-threatening conditions. In the interim, patient can be managed with suprapubic catheter to bypass the injured urethra.

Deferred Treatment

Deferred treatment policy involves immediate urinary diversion using suprapubic catheter followed by urethral repair after three months. Suprapubic catheter can be inserted percutaneously using Seldinger technique or with help of a trocar and canula in fully distended bladder. It can be done under ultrasound guidance if the bladder is not adequately distended and facility for ultrasonography (USG) is available. When the bladder is empty and USG facility is not available, open suprapubic cystostomy may be performed to put in the catheter. Open suprapubic catheterisation should be performed through a 3 cm vertical midline incision approximately 2 cm from public symphysis (Figure 1). The suprapubic catheter should then be left in the bladder for at least three months to allow for scar maturation.

Figure 1.

Photograph of a patient with suprapubic cystostomy. Note the correct site, in the midline, 1–2 cm above the pubic symphysis. This cystostomy has been done through an incision just adequate to admit the cystostomy tube.

Complications and Prognosis

The periprostatic tissue and neurovascular bundles are not manipulated in endoscopic repair techniques. Hence, the chances of impotence and incontinence with endoscopic techniques are much less than with now historical railroading technique. On the other hand, whereas deferred treatment approach invariably causes urethral stricture, the incidence of impotence and incontinence is much less (19% and 4%, respectively).3

The Indian Experience

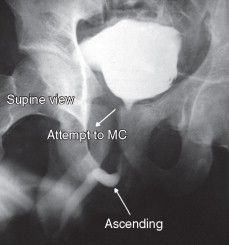

At our centres, as the facility of flexible cystoscopy is not available round the clock, most patients with urethral injuries are managed with deferred treatment approach. A trial of gentle urethral catheterisation is given to all patients with suspected urethral injuries, and if catheterisation trial fails, a retrograde urethrogram is performed. In patients with extravasation of dye, immediate urinary diversion is done via a suprapubic catheter. However, in patients who are haemodynamically unstable or who have associated life-threatening injuries, retrograde urethrography is omitted and suprapubic urinary diversion is done straightaway. A combined antegrade and retrograde urethrogram is done at 3–4 months of injury and the urethral stricture thus detected is treated accordingly (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Combined (retrograde + MC) showing non-opacification of posterior urethra suggesting stricture.

MC: micturating cystourethrogram

A total of 66 patients underwent various forms of urethroplasty for the treatment of post-traumatic posterior urethral stricture during the year 2009, at our centres, with a success rate of about 82% at one year. Ten patients had to undergo secondary procedures like optical internal urethrotomy (OIU) or urethral dilation for anastamotic site narrowing while two patients had to undergo redo-urethroplasty.

Another Indian study published in 2010 reported a similar experience from authors, who recommended delayed urethral repair as the standard of care in absence of availability of facilities and expertise for endoscopic urethral repair.17

Management of Female Urethral Injuries

Female urethral injuries are best assessed by urethroscopy. If urethroscopy cannot be performed, urethrography may be tried. In contrast to male patients, urethral trauma in females can't be managed with simple suprapubic diversion of urine, as it may lead to formation of urethrovaginal fistulae or stricture.18 Instead, in women with pelvic fractures accompanying proximal urethral disruption, immediate retropubic exploration and realignment of disrupted urethral ends with primary anastomosis over a catheter should be done. The lacerations in distal urethra can be managed by Foley's catheterisation and primary closure of the vaginal laceration.19

Anterior Urethral Injuries

Anterior urethral injuries are most often caused by ‘straddle’ injury or a kick to the perineum, which causes the bulbar urethra to crush against the pelvic bones. Other modes of anterior urethral injuries include gunshot or stab wounds, severe penile fracture or insertion of foreign bodies into the urethra resulting from direct trauma to the penis. Superficial injury to anterior urethral may also be caused iatrogenically if a Foley's catheter with an inflated balloon is pulled out; Foley's balloon is accidently inflated within the anterior urethra or during difficult cystoscopies.

Signs and Symptoms

The classical triad of bulbar urethral injuries includes:

-

•

Inability to void

-

•

Blood at meatus (most important sign)

-

•

Perineal haematoma.

Lacerations of the urethra result in extravasation of urine and blood from the urethra that spreads along the fascial planes of the perineum and penis. If Buck's fascia is intact, extravasation is confined to the penis, giving a ‘sleeve-like’ penile ecchymosis and swelling. When Buck's fascia is injured, extravasation extends into the perineum, as limited by Colle's fascia, and so creates the classical ‘butterfly sign’ haematoma. The ecchymosis can also extend on to the anterior abdominal wall, along Scarpa's fascia.1

Management

Goals of Treatment

As with posterior urethral injuries, the initial management of anterior urethral injuries is focused on detection and management of any associated life-threatening injuries and proper management of urethral injuries requires a prompt diagnosis and appropriate treatment plan. Extensive extravasation requires close observation for infection, tissue necrosis, and fasciitis.

Therapeutic Options

Simple contusion can be managed conservatively without catheterisation.1 But, urethral disruption should be managed with proper surgical repair, either immediate or delayed. Blind catheterisation may convert a partial tear into complete tear. A gentle attempt at catheterisation should be made only if facility of endoscopy is not available. If facilities are available, endoscopic primary realignment and urethral catheterisation is performed with the catheter left in situ for a minimum of four weeks.

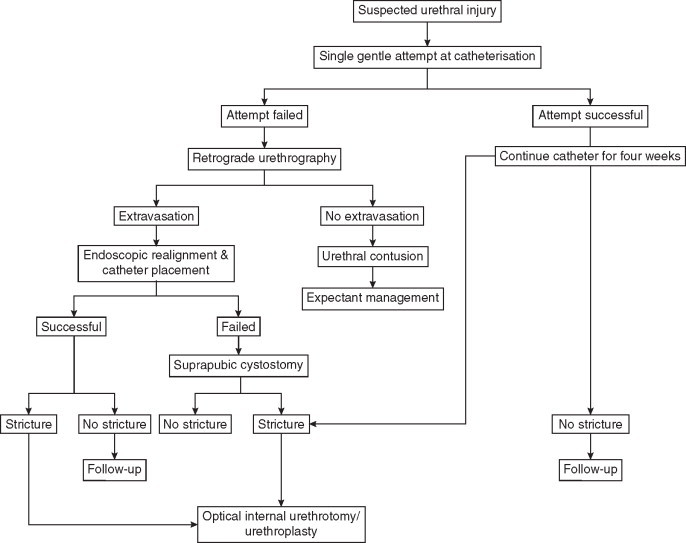

Our recommended approach to management of anterior urethral injuries is shown in Algorithm 2.

Algorithm 2.

Approach to management of anterior urethral injury.

Another option for management is by suprapubic urinary diversion for four weeks. Incomplete lacerations usually heal using this technique with a relatively low stricture rate of under 50%.20 The suprapubic tube can be removed after four weeks if normal voiding can be re-established and neither contrast extravasation nor stricture is present on urethrography. When strictures do occur they are typically short or flimsy and can be managed effectively by urethrotomy.1

For complete urethral disruption, a similar policy of either endoscopic realignment followed by catheter placement or supra pubic urinary diversion is used. Urethroplasty can then be performed as a planned second stage three or more months later.21,22 Immediate primary repair for complete anterior urethral disruption requires extensive debridement of devitalised tissue with subcutaneous drainage and can risk the integrity of corpus spongiosum.1

Conclusion

With the increase in the number of patients with trauma attending the emergency department of hospitals, the general surgeons now have to deal with complex and life-threatening injuries. In rural and semi-urban setting, management of trauma patients is all the more difficult because adequate facilities and appropriate expertise is not widely available, especially in the developing nations. For patients with urethral injuries, the management of other life-threatening injuries takes precedence. At places where appropriate facilities, instruments, and expertise for handling urethral injuries is not available, these injuries can best be managed using the Deferred Treatment Policy. The primary task of the emergency surgeon in such cases is to achieve temporary urinary diversion with a well-placed suprapubic cystostomy, done in the least traumatic way (Figure 1). The patient may then be referred to a centre with expertise in dealing with such injuries. This is the best way in which the patient can be managed, when the resources are limited.

Conflicts of Interest

None identified.

References

- 1.Klosterman PW, McAninch JW. Urethral injuries. AUA Update Series Vol. 8 Lesson. 1989;32:249–256. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Rosenstein DI, Alsikafi NF. Diagnosis and classification of urethral injuries. Urol Clin N Am. 2006;33:73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ucl.2005.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koraitim MM, Marzouk ME, Atta MA. Risk factors and mechanisms of urethral injury in pelvic fractures. Br J Urol. 1996;71:876. doi: 10.1046/j.1464-410x.1996.01119.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Andrich DE, Mundy AR. The nature of urethral injury in cases of pelvic fracture urethral trauma. J Urol. 2001;165:1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mouraviev VB, Coburn M, Santucci RA. The treatment of posterior urethral disruption associated with pelvic fractures: comparative experience of early realignment versus delayed urethroplasty. J Urol. 2005;173:873. doi: 10.1097/01.ju.0000152145.33215.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Spirnak JP. Pelvic fracture and injury to the lower urinary tract. Surg Clin North Am. 1988;68:1057. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)44636-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Perry MO, Husmann DA. Urethral injuries in female subjects following pelvic fractures. J Urol. 1992;147:139. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)37162-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Colapinto V, McCallum RW. Injury to male posterior urethra in fractured pelvis: a new classification. J Urol. 1977;118:575–580. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)58110-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goldman SM, Sandler CM, Corriere JN, McGuire EJ. Blunt urethral trauma: a unified, anatomical mechanical classification. J Urol. 1997;157:85–89. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(01)65291-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore EE, Cogbill TH, Malagoni MA. Organ injury scaling. Surg Clin North Am. 1995;75:293–303. doi: 10.1016/s0039-6109(16)46589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mitchell JP. Injuries to the urethra. Br J Urol. 1968;40:649. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shlamovitz GZ, McCullough L. Blind urethral catheterization in trauma patients suffering from lower urinary tract injuries. J Trauma-Injury Infect Crit Care. 2007;62:330–335. doi: 10.1097/01.ta.0000221768.68614.36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Onen A, Ozturk H, Kaya M, Otcu S. Long term outcome of posterior urethral rupture in boys: a comparison of different surgical modalities. Urology. 2005;65:1202–1207. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2005.01.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Martínez-Piñeiro L, Djakovic N, Plas E. EAU guidelines on urethral trauma. Eur Uro. 2010;57:791–803. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2010.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Elliott DS, Barrett DM. Long-term follow-up and evaluation of primary realignment of posterior urethral disruptions. J Urol. 1997;157:814. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shrinivas RP, Dubey D. Primary urethral realignment should be the preferred option for the initial management of posterior urethral injuries. Indian J Urol. 2010;26:310–313. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.65416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Philipraj SJ. Delayed repair is the ideal management for posterior urethral injuries-for the motion. Indian J Urol. 2010;26:305–309. doi: 10.4103/0970-1591.65414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morehouse DD. Management of posterior urethral rupture: a personal view. Br J Urol. 1988;61:375. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410x.1988.tb06578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pokorny M, Pontes JE, Pierce JM., Jr Urologic injuries associated with pelvic trauma. J Urol. 1979;121:455. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)56822-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Cass AS, Godec CJ. Urethral injury due to external trauma. Urology. 1978;11:607–611. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(78)90013-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hausmann DA, Boone TB, Wilson WT. Management of low velocity gunshot wounds to the anterior urethra: the role of primary repair versus urinary diversion alone. J Urol. 1993;150:70. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35399-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Selkowitz SM. Penetrating high velocity genitourinary injuries. Urology. 1977;9:371. doi: 10.1016/0090-4295(77)90209-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]