Introduction

Bezoars are concretions of foreign material in the gastrointestinal tract, mainly the stomach.

Chewing on and eating hair or any indigestible materials lead to the formation of a bezoar. Trichobezoar is a ball of swallowed hair that collects in the stomach and fails to pass through the intestines. They are confined within the stomach in most of the cases. However, rarely there is contiguous extension of trichobezoar through the pylorus into jejunum, ileum and even up to the colon. Such a condition is called the Rapunzel syndrome. The term comes from a story written by the Grimm brothers in 1812 about Rapunzel who was a long-haired maiden. She lowered her tresses to allow her prince charming to climb up to her prison tower to rescue her. This syndrome was first described in 1968 by Vaughan and since then till date just about 30 cases have been described in the literature.1

Case report

A 24-year-old female patient presented with pain in the abdomen, vomiting of 10 days duration, and constipation of three days duration. She was ill looking, dehydrated and had pallor. Abdomen was non-tender and distended. Bowel sounds were absent. Apart from haemoglobin which was 8 g% rest of the haematological and biochemical investigations were within normal limits. Plain radiograph of the abdomen showed three air fluid levels. Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CECT) abdomen revealed a large, well-circumscribed, non- homogeneous lesion in the lumen of the stomach that was composed of concentric whorls of different densities that had pockets of air enmeshed within it. This was suggestive of trichobezoar (Fig. 1). The patient underwent exploratory laparotomy through upper mid line incision. An intraluminal mass was seen and felt in the stomach and in the jejunum (Figs. 2 and 3). The jejunal lesion measuring 3 x 3 cm2 was located 3 ft from the duodeno-jejunal junction. The stomach was opened between the two stay sutures and a huge trichob- ezoar taking the shape of the stomach was seen. There was a long tail of hair extending through the pylorus into the small bowel. This was a case of a Rapunzel syndrome (Fig. 4). The trichobezoar of the stomach was removed. The remaining jejuna part was dislodged gently by milking it proximally and finally taken out through the gastrotomy opening. Gastrotomy was closed in two layers. The patient had an uneventful postoperative course and was placed under psychiatric care. In spite of repeated enquiry she as well as her relatives denied history of trichophagia.

Fig. 1.

Computed tomography scan suggesting trichobezoar.

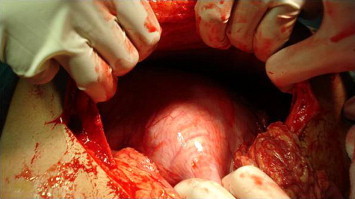

Fig. 2.

Body of trichobezoar in stomach.

Fig. 3.

Tail of trichobezoar obstructing the jejunum.

Fig. 4.

The complete trichobezoar with its tail.

Discussion

Trichobezoars are most commonly seen in females (approximately 90%) aged between 10 and 19 years but only in half of these patients is a history of trichophagia found. Around 30% of the patients with trichotillomania, a psychological condition that involves strong urges to pull hair, will engage in tri- chophagia. It is reported that only around 1% of patients who engage in trichophagia will go on to eat their hair to the extent that they require surgical removal.2 Trichobezoar form because hair being slippery get retained in gastric folds, escaping peristaltic propulsion. More and more hair accumulates and gets enmeshed into a ball and assumes the shape of the stomach. Decomposition and fermentation of trapped food often gives the bezoar, and the patient's breath, a putrid smell.3 Rapunzel syndrome is a rare form of trichobezoar, and various criteria have been used in its description in the literature. Some define it as a gastric trichobezoar with a tail extending up to the jejunum or beyond; and some still define it as a bezoar of any size which can cause intestinal obstruction.3 Both these criteria were met with in the case we encountered.

Trichobezoars can present with anaemia, abdominal pain, haematemesis, nausea and/or vomiting, bowel obstruction, gastric ulcers, perforation, gastrointestinal bleeding, acute pancreatitis, and obstructive jaundice.4 The complications of Rapunzel syndrome ranges from attacks of incomplete pyloric obstruction to complete obstruction of the bowel to perforation peritonitis and death.5

Examination of the patient in whom trichobezoar is suspected may reveal severe halitosis and patchy alopecia. Our patient did not have either of these findings. Imaging may show the bezoar as a mass or filling defect as seen by the CECT scan done by us. The gold standard for diagnosis though is upper gastrointestinal endoscopy.5-7

Successful management and treatment of a bezoar requires removal of the mass and prevention of recurrence. Method of removal depends on its consistency, size, and location. In the early stages endoscopic removal is possible, though however it should be reserved for small trichobezoars. Various other methods like extracorporeal shock wave lithotripsy, laser ignited mini-explosive technique, intragastric administration of enzymes (pancreatic lipase, cellulose), and medications (metoclopra- mide, acetylcysteine) have been reported with varying results. Open surgery still remains the corner stone of large trichobezoar removal especially if it has an extension into the bowel, which might be missed with other methods of treatment. Laparoscopy has been also used with limited success.3,6 Recurrences have been reported in the literature after the initial removal of bez- oars hence long-term psychiatric follow-up is advised.3,7

Conclusion

Trichobezoars are a bizarre medical problem, and Rapunzel syndrome is an extremely uncommon variety of trichobezoar. The diagnosis of trichobezoar is possible on imaging in a proper clinical setting. However, Rapunzel syndrome is most often an intraoperative finding. Even today open surgical removal forms the main stay of treatment. All patients with trichobez- oar should be referred for psychiatric evaluation after surgery to avoid recurrence.

Conflicts of interest

None identified.

References

- 1.Naik S., Gupta V., Naik S. Rapunzel syndrome reviewed and redefined. Dig Surg. 2007;24:157–161. doi: 10.1159/000102098. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Frey A.S., McKee M., King R.A., Martin A. Hair apparent: Rapunzel syndrome. Am J Psychiatry. 2005;162:242–248. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.242. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gonuguntla V., Joshi D.D. Rapunzel Syndrome—A Comprehensive Review of an Unusual Case of Trichobezoar. Clin Med Res. 2009;7:99–102. doi: 10.3121/cmr.2009.822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zent R.M., Cothren C.C., Moore E.E. Gastric trichobezoar and Rapunzel syndrome. J Am Coll Surg. 2004;199:990. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2004.03.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mohite P.N., Gohil A.B., Wala H.B., Vaza M.A. Rapunzel syndrome complicated with gastric perforation diagnosed on operation table. J GastrointestSurg. 2008;12:2240–2242. doi: 10.1007/s11605-007-0460-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gorter R.R., Kneepkens C.M.F., Mattens E.C.J.L., Aronson D.C., Heij H.A. Management of trichobezoar: case report and literature review. PediatrSurg Int. 2010;26:457–463. doi: 10.1007/s00383-010-2570-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Coulter R., Antony M.T., Bhuta P., Memon M.A. Large Gastric Trichobezoar in a Normal Healthy Woman: Case Report and Review of Pertinent Literature. South Med J. 2005;98:1042–1044. doi: 10.1097/01.smj.0000182175.55032.4a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]