Abstract

Oxycodone, an opioid with known abuse liability, is misused by the intranasal route. Our objective was to develop a model of intranasal oxycodone self-administration useful for assessing the relative reinforcing effects of opioids and potential pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorders. Healthy, sporadic intranasal opioid abusers (n=8; 7 M, 1 F) completed this inpatient 2.5-week, randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, crossover study. Each intranasal oxycodone dose (0, 14 & 28 mg) was tested in a separate 3-day block of sessions. The first day of each block was a sample session in which the test dose was given. Two randomized progressive ratio sessions were conducted on the next 2 days: 1) subjects could work for the test dose over 7 trials (1/7th of total dose/trial), and 2) subjects could work for either a portion of the dose (1/7th) or money ($3) over 7 trials. Physiological and subjective measures were collected before and after drug administration for all sessions. Subjects never worked to self-administer placebo regardless of whether money was available. In both self-administration sessions, oxycodone self-administration was dose-dependent. Subjects worked less for drug (28 mg oxycodone) when money was available, but only modestly so. Oxycodone dose-dependently increased VAS ratings of positive drug effects (e.g., ‘like’) during sample sessions (p<0.05). These reports were positively correlated with self-administration behavior (e.g., ‘like’, r=0.65). These data suggest that both procedures are sensitive for detecting the reinforcing properties of intranasal oxycodone and may be employed to further explore the characteristics of opioid compounds and potential pharmacotherapies for treatment.

Keywords: self-administration, intranasal, oxycodone, progressive-ratio, reinforcing efficacy

There is a rich literature supporting the effectiveness of opioids as analgesics for acute and chronic pain disorders (Berman et al., 1990; Eisenberg, Midbari, Haddad, & Pud, 2010; King, Reid, Forbes, & Hanks, 2011; Mercadante, 2010; Parker, Holtmann, & White, 1991). However, opioids exert their analgesic effects primarily through binding to mu opioid receptors (Pasternak, 2005), the same receptor system that contributes to their abuse liability. Rates of prescription opioid abuse have been on the rise in the United States for the past several years (SAMHSA, 2011a). It is estimated that there are 1.9 million individuals with prescription opioid abuse or dependence disorders in the United States (SAMHSA, 2011b). The rates of prescription opioid use, dependence, and diversion are recognized as particularly endemic among adolescents and younger adults. One opioid, oxycodone, is an effective prescription analgesic with a high potential for opioid abuse and physical dependence (DEA, 2009). Oral, intravenous and intranasal oxycodone administration have all been shown to be associated with substantial abuse liability in laboratory studies of non-dependent opioid abusers, who subjectively report dose-dependent increases in ratings on key measures, such as ‘liking’ and ‘good drug effects’ (Lofwall, Nuzzo, & Walsh, 2011; Stoops, Hatton, Lofwall, Nuzzo, & Walsh, 2010; Walsh, Nuzzo, Lofwall, & Holtman, 2008; J. P. Zacny & Gutierrez, 2009). Oxycodone abuse is on the rise, as evidenced by over 148,000 emergency room visits related to nonmedical use of oxycodone in 2009 (SAMHSA, 2011a). Furthermore, the number of oxycodone-related deaths has risen significantly since 1999 (CDC, 2011; Cone et al., 2003). For decades, there have been numerous unsuccessful attempts to develop a mu opioid analgesic, which lacks abuse liability while retaining potent analgesic properties. Development of valid and reliable experimental models that can assess abuse liability and reinforcing efficacy of both current and novel pharmacotherapies for pain and opioid addiction is necessary for the drug development process.

Non-human studies of drug self-administration have served for more than 40 years as the gold standard procedure for assessing abuse liability of drugs with CNS activity (Ator & Griffiths, 2003; Carter & Griffiths, 2009). Self-administration studies, typically conducted in rodent and non-human primates, are a required preclinical step in the Food and Drug Administration approval process for drugs with abuse potential (FDA, 2003). The paradigm is widely accepted as having excellent face validity with a high concordance rate between drugs self-administered in laboratory animals and those showing epidemiological evidence of abuse (Carter & Griffiths, 2009). Self-administration has been successfully adapted for use in the human laboratory to study the reinforcing efficacy of opioids, including heroin and prescription opioids (e.g., oxycodone) and to assess potential pharmacotherapies for substance use disorders (Comer et al., 2008). The earliest human studies examined the reinforcing efficacy of heroin, methadone or hydromorphone under an array of conditions, including detoxification (Altman, Meyer, Mirin, & McNamee, 1976; Meyer, Mirin, Altman, & McNamee, 1976) and maintenance with methadone (Jones & Prada, 1975; Stitzer, McCaul, Bigelow, & Liebson, 1983), buprenorphine (Mello & Mendelson, 1980; Mello, Mendelson, & Kuehnle, 1982) and naltrexone (Altman, et al., 1976; Mello, Mendelson, Kuehnle, & Sellers, 1981; Meyer, et al., 1976). More recent studies have employed various self-administration procedures to expand findings with pharmacotherapies including methadone (Donny, Brasser, Bigelow, Stitzer, & Walsh, 2005) and buprenorphine/naloxone (Comer, Walker, & Collins, 2005). With regard to oxycodone specifically, Comer and colleagues have demonstrated that intravenous oxycodone is self-administered by opioid-dependent individuals (Comer, Sullivan, Whittington, Vosburg, & Kowalczyk, 2008) and oral oxycodone is self-administered by non-dependent individuals (Comer, Sullivan, Vosburg, Kowalczyk, & Houser, 2010). While intranasal administration (i.e., snorting) of oxycodone is a common route of abuse and has been shown in the laboratory to be associated with significant abuse liability (Lofwall, et al., 2011; Walsh, Heilig, Nuzzo, Henderson, & Lofwall, 2012), no studies to date have examined self-administration of intranasal oxycodone in prescription opioid abusers.

Many self-administration studies employ alternative reinforcers as they can be used to examine the motivational factors involved in the reinforcing efficacy of drugs of abuse. To our knowledge, this is the first study to compare directly in the same study the presence and absence of an alternative reinforcer on intranasal opioid self-administration. The purpose of this study was to examine key parameters of intranasal oxycodone self-administration, including dose and influence of alternative reinforcers, with the aim of developing a model of intranasal prescription opioid self-administration useful for assessing the relative reinforcing effects of opioids and potential pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorders. The hypotheses of the study were that oxycodone would be self-administered following intranasal administration in a dose-dependent fashion, and that the presence of an alternative reinforcer (i.e., money) would result in completion of fewer ratios for active drug compared to the ratios completed for drug in the absence of an alternative reinforcer.

METHODS

Subjects

Eight (7 males, 1 female) recreational prescription opioid users were recruited by advertisements and admitted as inpatients. All were in good health according to medical history, physical examination, electrocardiogram and laboratory tests. Exclusion criteria included significant ongoing medical problems requiring daily medication, cardiovascular disease, hypertension, history of respiratory disorders and serious psychiatric illness outside of drug use. All subjects reported illicit opioid use (confirmed by urinalysis during multi-day intake). An opioid-negative urine sample also was required during screening in the absence of withdrawal symptoms to exclude opioid physical dependence. Individuals seeking treatment or successfully sustaining abstinence were excluded. Female patients were tested during screening, on entry and at weekly intervals for pregnancy with no positive results. The University of Kentucky (UK) Institutional Review Board approved this study; all subjects gave sober written informed consent and were paid for their participation. This study was conducted in accordance with the Helsinki guidelines for ethical human research. A Certificate of Confidentiality was obtained from the National Institutes of Health.

Drugs

This study was performed under an investigator-initiated Investigational New Drug Application (#69,214) with the Food and Drug Administration. Oxycodone hydrochloride powder was purchased from Spectrum Chemical Mfg. Corp. (Gardena, CA). All doses were fixed (not weight-based) and of equal volume to maintain the study blind. Lactose monohydrate powder (Mallinckrodt Chemical, Paris, KY) was used as the placebo.

Study Design

This 2.5-week study employed a randomized, double blind, placebo-controlled, within-subject design. It was conducted at the Clinical Research and Development Operations Center (CR-DOC), an inpatient research unit in the UK Hospital.

Experimental Sessions

Following admission, subjects were familiarized with and trained on all study procedures. Subjects were maintained on a caffeine-free diet, allowed a light breakfast 2 hours before session, and could smoke up to 30 minutes before session. Subjects participated in three sets of sessions (each set consisting of 1 sample session and 2 self-administration sessions [conducted on 3 consecutive days]) during the study. The first day of each set was a sample session during which subjects sampled an intranasal dose of oxycodone powder (0, 14 or 28 mg); these were presented in random order across session sets. Subjects split the powder into two lines and snorted one line through each nostril using a straw. Subjects were instructed that they could work for this dose during the self-administration sessions occurring on each of the following two days. Doses of oxycodone were chosen based upon a previous study from our laboratory demonstrating that similar intranasal doses (15 and 30 mg) produced significant increases in subjective ratings associated with abuse liability (Lofwall, et al., 2011) and would likely demonstrate reinforcing efficacy. Moreover, these doses are within the range of reported illicit intranasal doses used locally. Subject- and observer-rated measures (described below) were collected at baseline and at 5–30 minute intervals for 5 hours after drug administration. Questionnaires were presented electronically and completed by the subjects using a keyboard and/or computer mouse. A trained research assistant used a keyboard to initiate tasks and to enter observer-rated measures. Physiological measures were collected as described below.

Self-administration sessions were performed on the two days immediately following each sample session. Self-administration sessions utilized a progressive ratio schedule in which subjects were given the opportunity to work for the preceding sample dose. Subjects had the opportunity to work during each of seven trials. For each trial, the amount of required work (i.e., button pressing on the computer mouse) increased using a progressive ratio schedule (50, 250, 500, 1000, 1500, 2000 and 2500 responses). The number of button presses (with a programmed inter-response interval of 0.5 seconds) was displayed on the computer monitor until the response requirement was met. Two different self-administration procedures were examined under each dose condition. In the drug only procedure, subjects could work only for the test drug (i.e., no alternative reinforcer present), and each of the seven trials completed earned 1/7th of the total available dose. For example, completion of three trials when the sample dose was 28 mg would yield 3 × 1/7th of 28 mg or 12 mg total. In the drug/money procedure, subjects could work on the same response schedule, but were given the choice to respond for either 1/7th of the dose or a fixed amount of money during each trial (i.e., $3). The choice on each of the seven trials was independent (i.e., they could choose to work for any combination of money and/or drug over the seven trials). Thus, subjects could receive the full dose of oxycodone, a combination of oxycodone and money or the full payment of money (totaling $21 if the subject chose money during all work periods). Self-administration ended when the subject completed all trials, reported that they would no longer work, or after 30 minutes of no button pressing. If drug was chosen, subjects administered the appropriate dose based on the number of ratios completed. If money was chosen, the subjects were given the amount in cash (to increase salience of the reinforcer). The money was collected from the subject at the end of the session, and participants were given a receipt that recorded the amount of money added to their overall earnings. Subjects completed behavioral tasks every 15–30 minutes for up to 2 hours after their choice delivery. In an attempt to prevent lack of trial completion due to indolence, if subjects did not complete any trials during the drug only session or completed trials only for money during the drug/money session, subjects were required to remain in the session room for at least one hour. Behavioral tasks were not completed during this time. The order of self-administration sessions was randomized and counterbalanced so that one-half was drug only followed by drug versus money and the other half was the reverse.

Subject- and Observer-Rated Measures

Subject-rated measures included a visual analog scale (VAS), the Addiction Research Center Inventory (ARCI) short form, street value questionnaire and a subject- and observer-rated adjective checklist. The VAS questions were: “Do you feel any DRUG EFFECT?, How HIGH are you?, Does the drug have any GOOD effects?, Does the drug have any BAD effects?, How much do you LIKE the drug?, and How much do you DESIRE OPIATES right now?” (Walsh, et al., 2008). The subjects responded by positioning an arrow along a 100-point line ranging from 0 (‘not at all’) to 100 (‘extremely’). The street value questionnaire asked subjects to rate the street value of the dose they just received. The subject-rated adjective checklist consisted of 17 items rated from 0 (‘not at all’) to 4 (‘extremely’). The items were: skin itchy, turning of stomach, nodding, relaxed, coasting or spaced out, pleasant sick, talkative, heavy or sluggish feeling, dry mouth, drive, sleep, carefree, drunken, good mood, energetic, nervous and friendly (Fraser, Van Horn, Martin, Wolbach, & Isbell, 1961). The observer-rated opioid adjective checklist used the same 5-point scale described above, and items included nervous, skin itchy/scratching, friendly, nodding, relaxed, coasting or spaced out, talkative, heavy or sluggish feeling, sleepy, drunken, good mood and energetic (Fraser, et al., 1961). The ARCI short form was performed as previously described (Martin, Sloan, Sapira, & Jasinski, 1971). These have all been adapted and used in our previous work (Middleton, Nuzzo, Lofwall, Moody, & Walsh, 2011; Walsh, et al., 2008).

Physiological Measures

Oxygen saturation, heart rate and blood pressure were collected every minute using a Dinamap Non-Invasive Patient Monitor (GE Medical Systems, Tampa, FL). Recordings were made for 30 minutes before drug administration during the sample session and before the first trial of the self-administration sessions. Recordings continued for 5 hours and 2 hours after drug administration in the sample and self-administration sessions, respectively. Respiratory rate was determined by counting the number of breaths within 30 seconds and multiplying by 2. Pupil diameter was determined using a pupillometer (NeurOptics, San Clemente, CA) in constant lighting conditions. Respiratory rate and pupil diameter were collected on the same schedule as the subject- and observer-rated measures for all experimental sessions.

Statistical Analysis

All subject- and observer-rated measures from the sample sessions were analyzed as raw time-course data with two-factor within-subject analysis of variance (ANOVA; dose [3 levels] x time). Physiological measures collected every minute were averaged across time intervals (5–30 minutes) corresponding to collection of subjective reports. Peak scores following drug administration (maximum or minimum depending upon the a priori predicted direction of effect) were derived from time-course data and analyzed using one-factor ANOVA (dose [3 levels]). Subjective data from self-administration sessions were not analyzed as subjects could receive different doses. Number of trials completed for drug or money during self-administration sessions was analyzed using one-factor ANOVA (dose [3 levels]). Comparison of number of trials completed for each dose between the two types of self-administration sessions (drug only vs. drug/money) was performed using two-factor ANOVA (procedure [2 levels] x dose [3 levels]). Tukey post hoc tests were performed to explore main effects and interactions. Correlational analyses of subjective reporting during sample session to number of trials completed for drug during both self-administration sessions were performed using Spearman correlations. All ANOVA models were run with SAS 9.1 Proc-Mixed software for Windows and were considered significant when p < 0.05.

RESULTS

One subject was discharged before study completion for personal reasons. Of the eight who completed (seven male, one female), all were Caucasian with a mean [± standard error of the mean (SEM)] age of 35.5 (± 2.8) years. Subjects reported using illicit opioids 8 (± 1.4) days of the preceding 30 days. All subjects reported past or current intranasal opioid use. Average reported age of first use of illicit opioids was 21 (± 2) years, with a lifetime history use of opioids of 7.6 (± 2.7) years. Subjects also reported using cigarettes (n = 7), alcohol (n = 3), cocaine (n = 1), sedatives/hypnotics/tranquilizers (n = 3), marijuana (n = 2), methadone (n = 1) and heroin (n = 1) in the preceding 30 days.

Physiological and Subjective Outcomes: Sample Sessions

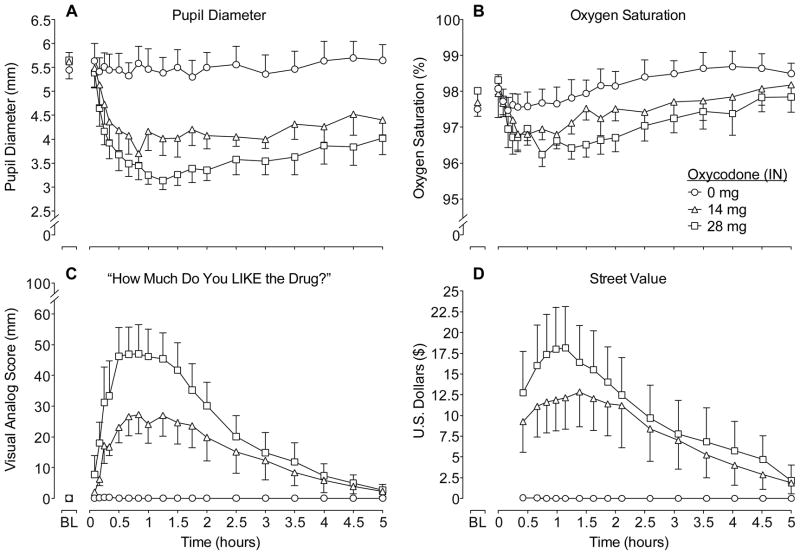

Figure 1 illustrates mean values for the time action curves for oxycodone and placebo during the first 5 hours after intranasal dosing on four outcomes. There were significant effects of dose and time on pupil diameter and a significant dose x time interaction (see figure legend for statistical outcomes; Figure 1A). Significant miosis was observed after both oxycodone doses compared to placebo; however, oxycodone doses did not differ significantly from one another. Analysis of trough pupil diameter revealed a main effect of dose (p<0.0001; Table 1) with both active doses different from placebo (p<0.0001) and from one another (p<0.05). There were modest, but insignificant, decreases on oxygen saturation in time-course (Figure 1B) and peak analyses (Table 1) as a function of oxycodone dose. Time-course and peak analyses of respiration rate revealed dose-dependent decreases following intranasal oxycodone (14 and 28 mg) administration compared to placebo (p<0.05; Table 1). Time-course analyses revealed no significant dose effects for heart rate, systolic or diastolic blood pressure. However, oxycodone significantly decreased peak heart rate (p<0.01; Table 1).

Figure 1.

Data shown are mean (n=8) values for pupil diameter (A), oxygen saturation (B), visual analog ratings of “How much do you LIKE the drug?” (C) and street value (D) for 5 hrs after drug administration during sample sessions. Error bars are SEM and presented unilaterally for clarity. Significant main effects of dose (F(2,14)=11.03; p<0.01) and time (F(18,126)=4.59; p<0.0001) and a dose x time interaction (F(36,252)=1.86; p<0.01) were found for pupil diameter. Significant main effects were found for oxygen saturation for time (F(19,133)=3.82; p<0.0001). Significant main effects of dose (F(2,14)=12.63; p<0.01), time (F(18,126)=6.51; p<0.0001) and a dose x time interaction (F(36,252)=2.34; p<0.0001) were found for visual analog ratings of “liking.” Significant main effects were found for street value for dose (F(2,14)=8.53; p<0.01) and time (F(14,98)=3.45; p<0.0001).

Table 1.

Peak scores for physiological, subjective and objective measures (n=8).

| Oxycodone Dose (mg)

|

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| 0

|

14

|

28

|

|

| Physiological | |||

| Pupil Diameter* | 5.1 (0.86) |

|

|

| Oxygen Saturation | 97.1 (0.43) | 96.4 (0.48) | 95.9 (0.35) |

| Respiration Rate* | 13.1 (0.86) | 11.3 (0.65) | 11.0 (0.76) |

| Heart Rate* | 65.4 (2.21) | 60.9 (2.59) | 60.3 (2.31) |

| Subject-Rated | |||

| VAS | |||

| Like* | 0.38 (0.38) | 33.88 (6.93) | 51.13 (9.04) |

| High* | 0.5 (0.5) | 33.00 (6.82) | 45.88 (10.0) |

| Good* | 0.38 (0.38) | 33.63 (6.91) | 46.63 (10.4) |

| Drug Effect* | 1.38 (1.02) | 32.88 (6.82) | 45.13 (9.99) |

| Street Value* | 0.08 (0.08) | 14.5 (4.91) | 18.2 (4.96) |

| Opioid Adjectives | |||

| Itchy* | 0.13 (0.12) | 1.13 (0.23) | 1.50 (0.27) |

| Relaxed* | 1.25 (0.25) | 1.88 (0.23) | 2.13 (0.23) |

| Coasting/Spaced Out* | 0.0 (0.0) | 0.50 (0.27) | 0.63 (0.26) |

| Talkative* | 0.25 (0.16) | 1.13 (0.13) | 1.50 (0.33) |

| Dry Mouth* | 0.13 (0.13) | 0.63 (0.26) | 0.75 (0.16) |

| Drive* | 0.63 (0.32) | 1.00 (0.33) | 1.50 (0.38) |

| Carefree* | 0.63 (0.38) | 1.00 (0.33) | 1.50 (0.38) |

| Friendly* | 1.38 (0.18) | 1.88 (0.23) | 2.25 (0.25) |

| Agonist* | 7.00 (1.67) | 13.6 (1.83) | 16.3 (2.09) |

| Observer-Rated Adjectives | |||

| Itchy* | 0.13 (0.13) |

|

|

| Friendly* | 1.63 (0.18) | 1.75 (0.25) | 2.25 (0.16) |

| Talkative* | 0.63 (0.18) | 1.50 (0.33) | 1.75 (0.25) |

| Good Mood* | 1.38 (0.18) | 1.88 (0.23) | 2.13 (0.13) |

| Energetic* | 0.25 (0.16) | 0.63 (0.18) | 1.25 (0.31) |

| Agonist* | 5.63 (0.98) | 9.00 (1.23) | 12.00 (0.78) |

Data are presented as mean (SEM).

Asterisk (*) indicates significant main effect of dose (p<0.05). Bold numbers indicate significant post-hoc difference from placebo (p<0.05). Boxed numbers indicate a significant post-hoc difference between the 14 and 28 mg oxycodone doses (p<0.05). Peak maximum scores are reported for all subject- and observer-rated measures. Nadir is reported for all physiological measures.

Data shown in Figure 1C illustrate mean VAS ratings for “How much do you LIKE the drug?” Oxycodone dose-dependently increased ratings of ‘like’ (p<0.001). While the 28 mg dose of oxycodone had higher peak ratings of ‘like’ (51.1±9.04) compared to 14 mg (33.9±6.93), this difference did not reach statistical significance. Subjective ratings of ‘high,’ ‘drug effect’ and ‘good drug effects’ also revealed significant dose-dependent effects (p<0.01; data not shown) over time. Peak analyses of VAS measures revealed significant dose effects for ratings of ‘high’, ‘drug effect’ and ‘good’ (p<0.01; Table 1). There were significant dose-dependent increases in ratings of street value in time-course and peak analyses (p<0.01; Figure 1D and Table 1), whereby the peak values were $14.50 (± 4.91) and $18.16 (± $4.96) for the 14 and 28 mg oxycodone doses, respectively.

Time-course analyses revealed significant dose effects for a number of prototypic opioid agonist symptoms including itchy, talkative, dry mouth and on the composite Agonist scale (p<0.05). Similarly, peak score analyses revealed endorsement of typical mu agonist effects as a function of dose including, itchy, relaxed, coasting or spaced out, talkative, dry mouth, drive, carefree, friendly and on the composite Agonist scale (p<0.05; Table 1). Time-course and peak analyses of the observer-rated signs revealed dose-related increases on itchy, talkative, good mood, energetic and on the composite Agonist scale (p<0.05; Table 1). Peak analyses also revealed a significant increase in observer ratings of friendly.

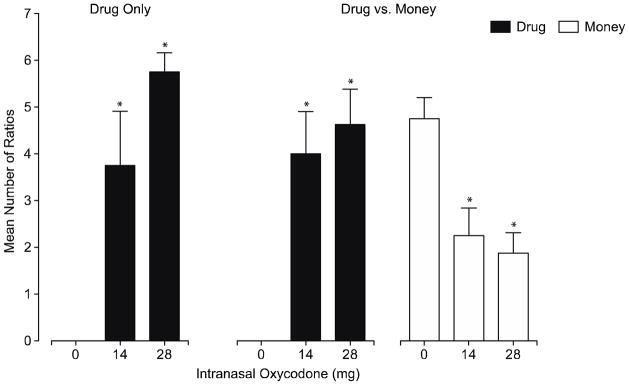

Self-administration: Progressive ratio sessions

Figure 2 shows the mean number of ratios completed for placebo and oxycodone during the sessions when only drug was available (left panel) versus sessions when subjects were able to work for either drug or money (right panels). In both experimental procedures, no subject ever worked for placebo. Subjects completed significantly more ratios for both the 14 and 28 mg oxycodone doses compared to placebo (p<0.01) in both procedures, and oxycodone self-administration was dose-dependent. When money was available as an alternative reinforcer to placebo, subjects worked for money an average of 4.75 of 7 possible trials. Significantly fewer trials were completed for money when 14 mg (2.25±0.59) and 28 mg (1.88±0.44) of oxycodone were available compared to placebo (p<0.01). Subjects worked less for drug when money was an available alternative reinforcer after the 28 mg dose (completed 4.63±0.75 trials) compared to the drug only session (5.75±0.41 trials), but this did not reach significance. This is also reflected in breakpoint values whereby the breakpoint for 28 mg during the drug/money session was lower (1438±274) than the breakpoint for the same dose during the drug only session (1875±206). Subjects self-administered 18.5 (±3.0) out of 28 mg oxycodone during the drug/money session compared to 23.0 mg (±1.65) during the drug only session. Breakpoint values and total oxycodone self-administered were similar regardless of the absence or presence of an alternative reinforcer in the 14-mg test condition. There was a significant (p<0.01) positive correlation between total ratios completed for drug and subjective ratings of positive drug effects collected in sample sessions, including ‘drug effect’ (r=0.65), ‘high’ (r=0.66), ‘good effects’ (r=0.65), ‘like’ (r=0.63) and ‘street value’ (r=0.66). Of the 32 total active drug progressive ratio sessions (this excludes all sessions when placebo was available), subjects completed all ratios for drug in only seven sessions and completed 0 ratios for drug in only six sessions.

Figure 2.

Data shown are number of ratios completed for drug during the drug only sessions (left panel) and for drug (middle panel) and money (right panel) during the drug vs. money sessions. Data are mean + SEM (n=8). Asterisk (*) indicates significant difference from placebo (within panel).

DISCUSSION

This study was designed to develop a valid method of intranasal opioid self-administration, a route by which opioids are often misused. We evaluated two self-administration procedures utilizing progressive ratio schedules in the presence and absence of an alternative reinforcer (i.e., money) to test the reinforcing efficacy of three oxycodone doses (0, 14 and 28 mg). During sample sessions, oxycodone (14 and 28 mg) produced prototypical dose-dependent mu opioid agonist effects on subjective ratings associated with abuse liability (e.g., ‘like’, ‘street value’) and on physiological measures including pupil diameter and respiratory rate. Subjects never worked to self-administer placebo under either schedule of reinforcement. However, subjects did work for money when placebo was available. In contrast to placebo, subjects reliably worked to self-administer intranasal oxycodone in both procedures, demonstrating that both models were sensitive at detecting the reinforcing effects of oxycodone. Subjects tended to work more for the high dose of oxycodone compared to the low dose (particularly during the drug only session); however, the number of ratios completed did not statistically differ between doses. Furthermore, there was a small, although insignificant, decrease in the number of ratios completed for drug when money was available as an alternative reinforcer. There was a significant correlation between subjective reporting during sample session and the number of ratios completed for drug during the self-administration sessions. The schedule utilized in the current study was sufficiently difficult such that not all subjects were completing every ratio for drug, but not so difficult that all ratios could not be completed if subjects were motivated to receive the full dose of drug.

In the current study, money was employed as the alternative reinforcer. There are several other reinforcers that have been used in human self-administration studies with alcohol and cocaine, including food (Stoops, Lile, & Rush, 2010; J.P. Zacny, Divane, & de Wit, 1992) and vouchers for merchandise (Hart, Haney, Foltin, & Fischman, 2000). However, results from these studies demonstrate that money is generally one of the most efficacious alternative reinforcers for reducing drug-taking behavior. For example, Hart and colleagues (2000) determined that both vouchers for money and merchandise decreased cocaine self-administration, but vouchers for money did so to a greater extent. Prior studies have explored the use of alternative reinforcers with opioid self-administration. Specifically, Comer and colleagues conducted a study in morphine-maintained individuals in which the intranasal heroin dose response curve for breakpoint was shifted successively downward as the value of the alternative reinforcer ($10, $20 & $40) increased (Comer, Collins, & Fischman, 1997). A similar result was found with methadone, where methadone self-administration decreased as the amount of money as an alternative reinforcer increased (Stitzer, et al., 1983). However, in a different study, morphine-maintained subjects were given the opportunity to self-administer intravenous heroin versus varying amounts of money (Comer et al., 1998). In this instance, subjects completed more ratios for heroin when $10 was available compared to when $20 was available (as expected), but self-administration when $40 was available was comparable to the $10 condition. It is unclear what accounted for the lack of orderliness for these functions (e.g., a small N [5], carryover effects from more than once daily drug administration), but these data suggest that the amount of money should be explored carefully in the context of the other experimental conditions under study.

One potential limitation of the current study is that the amount of money that was offered as an alternative reinforcer was carefully selected to reflect the street value of an oxycodone dose if purchased in the Central Kentucky area (where individuals pay approximately $1/mg of oxycodone). Studies conducted elsewhere may need to customize the values of alternative reinforcers to reflect the local street value and other economic factors. Subjects completed ratios for the amount of money ($3) offered as a reinforcer, suggesting that the amount of money offered was, in fact, reinforcing. Interestingly, in the condition where subjects could work for only money or placebo, subjects did not complete all of the ratios to earn the maximum amount of money available. Another limitation is low enrollment of females in this study precluding any exploration of potential gender differences.

The progressive ratio procedure was chosen for the current study because it has been shown to be sensitive and efficient, and it yields orderly outcomes. Other procedures, such as choice procedures, have been employed to examine opioids, but because of their typically long duration of action, these studies can be cumbersome in design and require a lengthy inpatient stay for completion (Donny, et al., 2005). In typical progressive ratio studies, completion of a single ratio results in immediate delivery of the dose, with multiple doses administered within the same session, to determine breaking point. This is easily accomplished with very short-acting drugs (Walsh, Donny, Nuzzo, Umbricht, & Bigelow, 2010). However, to preclude cumulative drug effects when studying longer acting agents (this would include most opioids), conditions have been modified to allow subjects to work through the progressive ratio schedule earning a portion of the total dose with each completed ratio, with the total dose earned delivered only after the work requirements are completed (Comer, et al., 1998).

Employing this modification, the present data reveal that progressive ratio responding for intranasal oxycodone is orderly and dose-dependent, and readily discriminates placebo from active drug. Moreover, self-administration of active drug was modestly reduced by an alternative reinforcer (i.e., money); however, money did not completely suppress drug taking suggesting that greater amounts of money (i.e., higher than the estimated street value) may be required to achieve that goal. Importantly, these oxycodone doses under the present test conditions did not produce, on average, maximal drug taking behavior, suggesting that these test procedures would be sensitive for assessing outcomes of either increased or decreased drug taking. Therefore, these procedures may be useful for future studies that examine the relative reinforcing efficacy of existing or novel opioids and for investigating potential pharmacotherapies for opioid use disorders.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Rebecca Jude and Victoria Vessels for their technical research support, and Stephen Sitzlar, Pharm.D. for pharmacy services. The authors are indebted to the UK Clinical Research Development and Operations Center for in-patient services, nursing supervision and nutritional services.

Footnotes

Disclosures

This project was supported by the National Institute on Drug Abuse (R01-DA016718, S.L.W.; R01-DA027031, S.L.W.) and National Institutes of Health (UL1RR033173). The funding source had no other role other than financial support.

All authors contributed in a significant way to the manuscript and all authors have read and approved the final manuscript.

There are no conflicts of interest to report.

References

- Altman JL, Meyer RE, Mirin SM, McNamee HB. Opiate antagonists and the modification of heroin self-administration behavior in man: an experimental study. The International Journal of the Addictions. 1976;11:485–499. doi: 10.3109/10826087609056165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ator NA, Griffiths RR. Principles of drug abuse liability assessment in laboratory animals. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2003;70:S55–72. doi: 10.1016/S0376-8716(03)00099-. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berman ML, Briggs GG, Bogh P, Mannel R, Manetta A, DiSaia PJ. Simplified postoperative patient-controlled analgesia on a gynecologic oncology service. Gynecologic Oncology. 1990;38:55–58. doi: 10.1016/0090-8258(90)90011-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carter LP, Griffiths RR. Principles of laboratory assessment of drug abuse liability and implications for clinical development. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;105:S14–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.04.003. doi:10.1016/j.drugalcdep. 2009.04.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- CDC. Drug Overdose Deaths - Florida, 2003–2009. Center for Disease Control and Prevention. MMWR. 2011;60:869–872. [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Ashworth JB, Foltin RW, Johanson CE, Zacny JP, Walsh SL. The role of human drug self-administration procedures in the development of medications. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;96:1–15. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.03.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Collins ED, Fischman MW. Choice between money and intranasal heroin in morphine-maintained humans. Behavioural Pharmacology. 1997;8:677–690. doi: 10.1097/00008877-199712000-00002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Collins ED, Wilson ST, Donovan MR, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Effects of an alternative reinforcer on intravenous heroin self-administration by humans. European Journal of Pharmacology. 1998;345:13–26. doi: 10.1016/S0014-2999(97)01572-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Vosburg SK, Kowalczyk WJ, Houser J. Abuse liability of oxycodone as a function of pain and drug use history. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;109:130–138. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.12.018. doi:10.1016/j.drug alcdep.2009.12.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Walker EA, Collins ED. Buprenorphine/naloxone reduces the reinforcing and subjective effects of heroin in heroin-dependent volunteers. Psychopharmacology. 2005;181:664–675. doi: 10.1007/s00213-005-0023-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cone EJ, Fant RV, Rohay JM, Caplan YH, Ballina M, Reder RF, Haddox JD. Oxycodone involvement in drug abuse deaths: a DAWN-based classification scheme applied to an oxycodone postmortem database containing over 1000 cases. Journal of Analytical Toxicology. 2003;27:57–67. doi: 10.1093/jat/27.2.57. discussion 67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DEA. Drugs and Chemicals of Concern: Oxycodone. Office of Diversion Control. 2009 http://www.deadiversion.usdoj.gov/drugs_concern/oxycodone/summary.htm.

- Donny EC, Brasser SM, Bigelow GE, Stitzer ML, Walsh SL. Methadone doses of 100 mg or greater are more effective than lower doses at suppressing heroin self-administration in opioid-dependent volunteers. Addiction. 2005;100:1496–1509. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2005.01232.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eisenberg E, Midbari A, Haddad M, Pud D. Predicting the analgesic effect to oxycodone by ‘static’ and ‘dynamic’ quantitative sensory testing in healthy subjects. Pain. 2010;151:104–109. doi: 10.1016/j.pain.2010.06.02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- FDA. Abuse Liability Assessment and Drug Dependence: Scientific and Regulatory Considerations in Drug Development. 2003 http://www.fda.gov/downloads/AboutFDA/CentersOffices/OfficeofMedicalProductsandTobacco/CDER/UCM180870.pdf.

- Fraser HF, Van Horn GD, Martin WR, Wolbach AB, Isbell H. Methods for evaluating addiction liability. (A) “Attitude” of opiate addicts toward opiate-like drugs. (B) a short-term “direct” addiction test. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1961;133:371–387. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart CL, Haney M, Foltin RW, Fischman MW. Alternative reinforcers differentially modify cocaine self-administration by humans. Behavioural Pharmacology. 2000;11:87–91. doi: 10.1097/00008877-200002000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones BE, Prada JA. Drug-seeking behavior during methadone maintenance. Psychopharmacologia. 1975;41:7–10. doi: 10.1007/BF00421297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King SJ, Reid C, Forbes K, Hanks G. A systematic review of oxycodone in the management of cancer pain. Palliative Medicine. 2011;25:454–470. doi: 10.1177/0269216311401948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lofwall MR, Nuzzo PA, Walsh SL. Effects of cold pressor pain on the abuse liability of intranasal oxycodone in male and female prescription opioid abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2011 doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2011.11.01. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martin WR, Sloan JW, Sapira JD, Jasinski DR. Physiologic, subjective, and behavioral effects of amphetamine, methamphetamine, ephedrine, phenmetrazine, and methylphenidate in man. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1971;12:245–258. doi: 10.1002/cpt1971122part1245. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH. Buprenorphine suppresses heroin use by heroin addicts. Science. 1980;207:657–659. doi: 10.1126/science.7352279. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Kuehnle JC. Buprenorphine effects on human heroin self-administration: an operant analysis. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1982;223:30–39. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mello NK, Mendelson JH, Kuehnle JC, Sellers MS. Operant analysis of human heroin self-administration and the effects of naltrexone. The Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics. 1981;216:45–54. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercadante S. Management of cancer pain. Internal and Emergency Medicine. 2010;5:S31–35. doi: 10.1007/s11739-010-0448-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer RE, Mirin SM, Altman JL, McNamee HB. A behavioral paradigm for the evaluation of narcotic antagonists. Archives of General Psychiatry. 1976;33:371–377. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.1976.01770030073011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Middleton LS, Nuzzo PA, Lofwall MR, Moody DE, Walsh SL. The pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic profile of intranasal crushed buprenorphine and buprenorphine/naloxone tablets in opioid abusers. Addiction. 2011;106:1460–1473. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2011.03424.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker RK, Holtmann B, White PF. Patient-controlled analgesia. Does a concurrent opioid infusion improve pain management after surgery? Journal of the American Medical Association. 1991;266:1947–1952. doi: 10.1001/jama.266.14.1947. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pasternak GW. Molecular biology of opioid analgesia. Journal of Pain and Symptom Management. 2005;29:S2–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2005.01.011. doi:10.1016/j.jpain symman.2005.01.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2009: National Estimates of Drug-Related Emergency Department Visits. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011a. HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4659, DAWN Series D-35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAMHSA. Results from the 2010 National Survey on Drug Use and Health: Summary of National Findings. Rockville, MD: Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration; 2011b. NSDUH Series H-41, HHS Publication No. (SMA) 11-4658. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stitzer ML, McCaul ME, Bigelow GE, Liebson IA. Oral methadone self-administration: effects of dose and alternative reinforcers. Clinical Pharmacology and Therapeutics. 1983;34:29–35. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1983.124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Hatton KW, Lofwall MR, Nuzzo PA, Walsh SL. Intravenous oxycodone, hydrocodone, and morphine in recreational opioid users: abuse potential and relative potencies. Psychopharmacology. 2010;212:193–203. doi: 10.1007/s00213-010-1942-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stoops WW, Lile JA, Rush CR. Monetary alternative reinforcers more effectively decrease intranasal cocaine choice than food alternative reinforcers. Pharmacology, Biochemistry, and Behavior. 2010;95:187–191. doi: 10.1016/j.pbb.2010.01.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Donny EC, Nuzzo PA, Umbricht A, Bigelow GE. Cocaine abuse versus cocaine dependence: cocaine self-administration and pharmacodynamic response in the human laboratory. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2010;106:28–37. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.07.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Heilig M, Nuzzo PA, Henderson P, Lofwall MR. Effects of the NK(1) antagonist, aprepitant, on response to oral and intranasal oxycodone in prescription opioid abusers. Addiction Biology, ePub ahead of print. 2012 doi: 10.1111/j.1369-1600.2011.00419.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh SL, Nuzzo PA, Lofwall MR, Holtman JR., Jr The relative abuse liability of oral oxycodone, hydrocodone and hydromorphone assessed in prescription opioid abusers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2008;98:191–202. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.05.00. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Divane WT, de Wit H. Assessment of magnitude and availability of a non-drug reinforcer on preference for a drug reinforcer. Human Psychopharmacology. 1992;7:281–286. [Google Scholar]

- Zacny JP, Gutierrez S. Within-subject comparison of the psychopharmacological profiles of oral hydrocodone and oxycodone combination products in non-drug-abusing volunteers. Drug and Alcohol Dependence. 2009;101:107–114. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2008.11.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]