SUMMARY

Asymmetric self-renewing division of neural precursors is essential for brain development. Partition defective (Par) proteins promote self-renewal, and their asymmetric distribution provides a mechanism for asymmetric division. Near the end of neural development, most asymmetric division ends and precursors differentiate. This correlates with Par protein disappearance, but mechanisms that cause downregulation are unknown. MicroRNAs can promote precursor differentiation, but have not been linked to Par protein regulation. We tested a hypothesis that microRNA miR-219 promotes precursor differentiation by inhibiting Par proteins. Neural precursors in zebrafish larvae lacking miR-219 function retained apical proteins, remained in the cell cycle and failed to differentiate. miR-219 inhibited expression via target sites within the 3’ untranslated sequence of pard3 and prkci mRNAs, which encode Par proteins, and blocking miR-219 access to these sites phenocopied loss of miR-219 function. We propose that negative regulation of Par protein expression by miR-219 promotes cell cycle exit and differentiation.

INTRODUCTION

Following neural induction in vertebrate embryos, neural precursor cells initially divide symmetrically to expand the precursor population. After a period of tissue growth, many precursors switch to asymmetric division, producing both new precursors to maintain the population and cells that differentiate as neurons or glial cells, either directly or after a limited number of transit-amplifying divisions. Near the end of embryogenesis, most precursors exit the cell cycle and differentiate, although some may become quiescent or be maintained into adulthood as stem cells. A balance of symmetric proliferative divisions, asymmetric self-renewing divisions and terminal differentiation assures production of appropriate numbers of neural cells to build a functional brain (reviewed in Huttner and Kosodo, 2005; Gönczy, 2008). Mechanisms that maintain that balance remain incompletely understood.

One mechanism that clearly contributes to neural precursor maintenance and differentiation involves neuroepithelial polarity (reviewed in Shitamukai and Matsuzaki, 2012; Fietz and Huttner, 2011; Götz and Huttner, 2005). After closure of the neural tube, apical membranes of neural precursors line a lumen, which subsequently forms the ventricles and central canal of the central nervous system. Associated with the apical membrane are various protein complexes, including one consisting of the Partitioning defective (Par) proteins Pard3, Pard6 and Prcki, also known as atypical Protein Kinase C (aPKC). Experiments performed in Drosophila provide strong evidence that unequal distribution of apical Par proteins during neural precursor division determines the fate of the progeny cells. In particular, cells that inherit apical Par proteins remain as precursors whereas those that do not enter a differentiation pathway (Prehoda, 2009). Data from vertebrate models are generally compatible with the idea that, in asymmetric divisions, high levels of apical Par proteins are associated with neural precursor self-renewal whereas low levels lead to differentiation (Bultje et al., 2009; Costa et al., 2008; Kosodo et al., 2004), although studies performed in zebrafish indicated that Pard3 can inhibit self-renewal and promote differentiation (Alexandre et al., 2010; Dong et al., 2012). The basis for these apparently conflicting conclusions is not known. At the end of embryogenesis, the uniform disappearance of Par proteins from apical membranes of neural precursors correlates with their terminal exit from the cell cycle and differentiation (Costa et al., 2008). Although the mechanistic basis of unequal Par protein distribution to progeny cells undergoing asymmetric self-renewing division has been thoroughly investigated, no mechanism that promotes disappearance of Par proteins from precursors fated to undergo terminal differentiation has been described.

microRNAs (miRNAs) are small noncoding RNAs that in most circumstances inhibit gene expression by mediating degradation or translational inhibition of target mRNAs (reviewed in Bartel, 2009). miRNAs regulate numerous developmental processes, but identification of authentic miRNA targets and the mechanistic functions that targeting fulfills in vivo remains daunting because most miRNAs potentially bind dozens, if not hundreds, of target mRNAs and many mRNAs have multiple sequences that could be bound by miRNAs (reviewed in Bartel, 2009; Asuelime and Shi, 2012). Nevertheless, recent data have begun to identify some roles for miRNAs in regulating neural precursor division and differentiation. In particular, several studies using mouse, zebrafish and frog have shown that miR-9 can drive precursors from the cell cycle and promote neuronal differentiation by regulating expression of multiple transcription factors, including Foxg1, Meis2, Gsh2, Hes1, Her6, Zic5 and Hairy1 (Shibata et al., 2011; Tan et al., 2012; Coolen et al., 2012; Bonev et al., 2011). Neuronal differentiation also is driven by miR-9 and let-7b through inhibition of the nuclear receptor TLX (Zhao et al., 2009) and by miR-124, which represses expression of the RNA-binding protein PTBP (Makeyev et al., 2007) and the transcription factor Sox9 (Cheng et al., 2009). Given the large number of miRNAs expressed by neural cells and their multitudes of potential target mRNAs, these advances likely provide only a partial understanding of the mechanisms by which miRNAs regulate neural precursor maintenance and differentiation.

Here we report evidence of neural precursor regulation by miR-219, an evolutionarily conserved miRNA expressed in zebrafish brain (Kapsimali et al., 2007). We previously noted that knockdown of miR-219 in zebrafish caused a deficit of oligodendrocyte progenitor cells (OPCs) (Zhao et al., 2010), raising the possibility that miR-219 promotes formation of glial cells from neural precursors. Target prediction software identified potential miR-219 target sites within the 3’ untranslated (UTR) sequences of Pard3 and Prkci genes in multiple species. Therefore, we hypothesized that miR-219 promotes transition of neural precursors from self-renewal to differentiation by negatively regulating Pard3 and Prkci. Our work now shows that pard3 and prkci mRNAs are functionally relevant targets of miR-219 in zebrafish. Loss of miR-219 function results in prolonged maintenance of apically localized proteins and retention of neural precursors in the cell cycle at the expense of late-born neurons and glial cells, indicating that mir-219 contributes to a microRNA-based mechanism that promotes neural cell differentiation.

RESULTS

miR-219Promotes Neural Precursor Exit from Proliferative Division

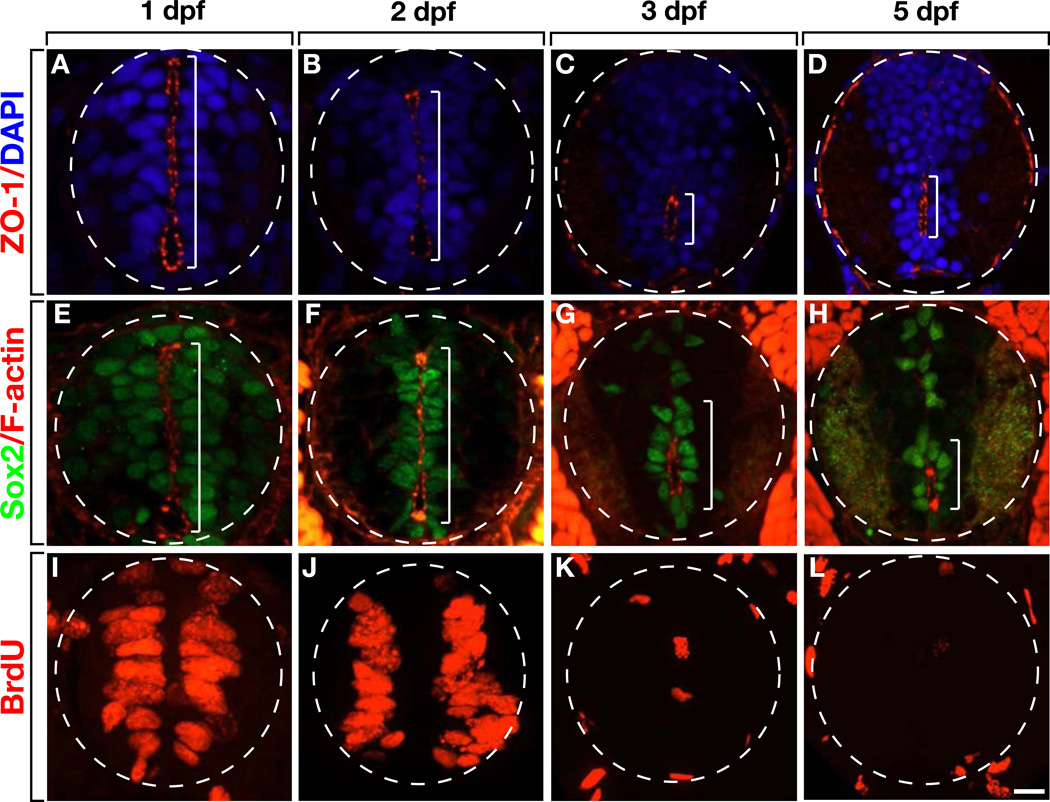

To test the hypothesis that miR-219 promotes neural precursor differentiation, we first set out to better characterize changes in precursor characteristics during zebrafish spinal cord development. In cat (Böhme, 1988) and rat (Sevc et al., 2009) a primitive lumen, extending across nearly the entire extent of the dorsoventral axis of the neural tube, transforms into a much smaller, ventrally positioned central canal. Initiation of this transformation coincides with exit of neural precursors from the cell cycle and completion of neurogenesis in late embryonic stage. The zebrafish spinal cord undergoes a similar transformation. At 1 and 2 days post fertilization (dpf), the tight junction-associated protein ZO-1 was enriched at the apical membranes of cells lining a primitive lumen spanning the spinal cord (Figures 1A and 1B). At 3 and 5 dpf, apical ZO-1 enrichment was no longer evident dorsally but remained associated with a central canal in ventral spinal cord (Figures 1C and 1D). F-actin was similarly localized, lining the primitive lumen at 1 and 2 dpf (Figures 1E and 1F) but limited to the central canal at 3 and 5 dpf (Figures 1G and 1H). This loss of apical protein enrichment coincided with loss of neural precursors. Whereas numerous cells lining the primitive lumen expressed Sox2, a marker of neural precursors (Ellis et al., 2004), at 1 and 2 dpf (Figures 1E and 1F), fewer Sox2+ cells remained at 3 and 5 dpf and these were mostly restricted to the area bordering the central canal (Figures 1G and 1H). Similarly, many cells lining the primitive lumen incorporated the thymidine analog BrdU, a marker of cells in S phase, at 1 and 2 dpf (Figures 1I and 1J), but few spinal cord cells incorporated BrdU at 3 and 5 dpf (Figures 1K and 1L). Therefore, by early larval stage most spinal cord precursors differentiate or become mitotically quiescent, concomitant with transformation of a primitive lumen to a central canal and loss of apically enriched proteins.

Figure 1. Loss of Apical Polarity Correlates With Loss of Neural Precursors and Lumen Morphogenesis.

All images show representative transverse sections at the level of the trunk spinal cord with dorsal up. (A and B) At 1 and 2 dpf, ZO-1 is concentrated at apical membranes of cells lining a primitive lumen, which extends across the dorsoventral axis of the spinal cord (brackets). (C and D) At 3 and 5 dpf the primitive lumen is replaced with a ventrally positioned central canal marked by apically localized ZO-1. (E–H) F-actin is similarly localized to apical membranes lining the primitive lumen and central canal. Additionally, most cells that express Sox2 are associated with F-actin localization. (I–L) A BrdU pulse labels numerous cells lining the primitive lumen at 1 and 2 dpf, but at 3 and 5 dpf few cells incorporate BrdU. Scale bar equals 10 µm.

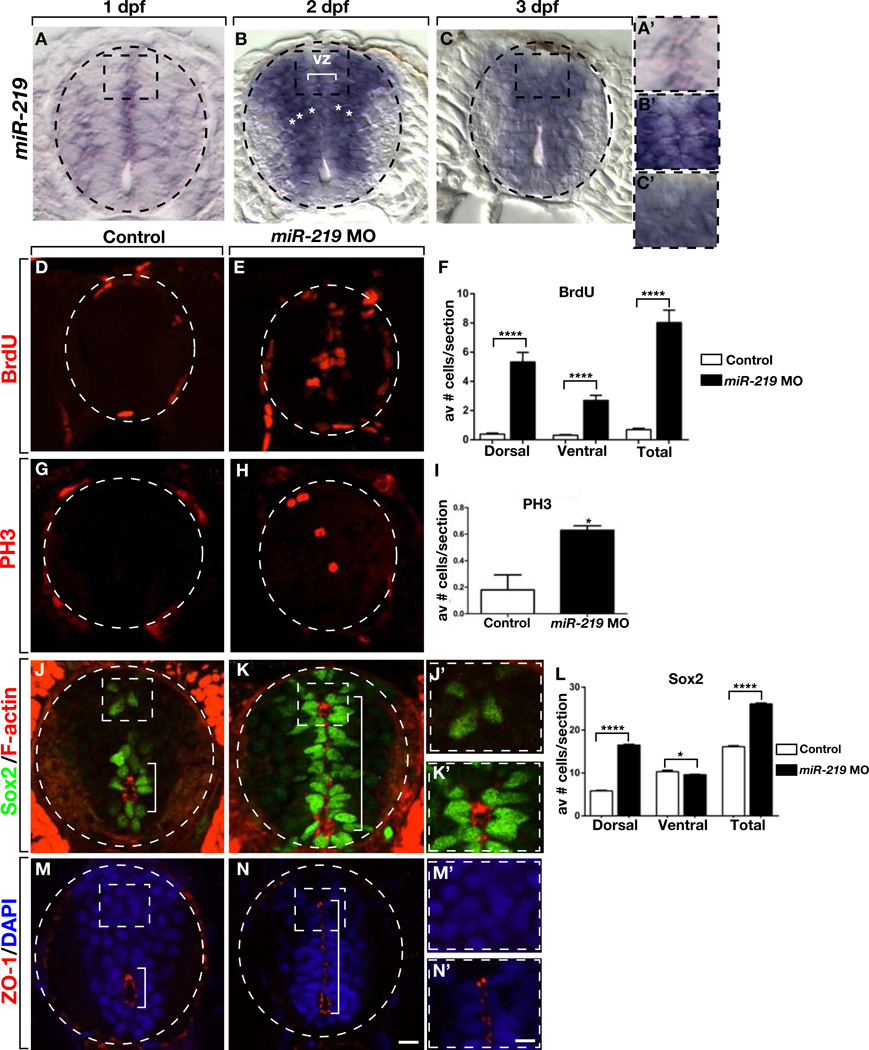

To investigate if miR-219 expression correlates with the morphological and neural precursor changes described above, we first performed quantitative PCR. This showed that miR-219 levels were relatively low prior to 1 dpf and then peaked at 2 dpf (Figure S1). We then carried out in situ hybridization using a locked nucleic acid (LNA) probe designed to detect the mature miR-219 sequence. At 1 dpf, spinal cord cells expressed mir-219 very weakly (Figure 2A) but by 2 dpf, miR-219 expression was robust (Figure 2B). Notably, miR-219 expression appeared to be highest in the cells just outside the proliferative ventricular zone and somewhat lower in the neural precursors immediately adjacent to the primitive lumen. At 3 dpf, after transformation of the primitive lumen to the central canal, cells throughout the medial spinal cord expressed miR-219 at uniform levels (Figure 2C). At 5 dpf, following completion of embryonic neurogenesis and gliogenesis, mir-219 expression in spinal cord was no longer evident (data not shown). Therefore, the pattern of miR-219 expression is consistent with the possibility that it regulates cell division and differentiation.

Figure 2. miR-219 Knockdown Causes Retention of Embryonic Spinal Cord Precursors into Postembryonic Stage.

All images show representative transverse sections through trunk spinal cord with dorsal up. (A–C) In situ hybridization to detect the mature form of miR-219 reveals low expression at 1 dpf but prominent expression at 2 dpf. Staining appears most intense in cells (asterisks) lateral to ventricular zone cells (vz, bracket) lining the primitive lumen. At 3 dpf miR-219 expression appears uniform in medial spinal cord. Boxed areas are shown in higher magnification in A’–C. (D and E) 3 dpf miR-219 MO-injected larva has more cells that incorporate BrdU than a control larva. (F) Graph showing the number of BrdU+ cells in the ventral, dorsal and entire spinal cord at 3 dpf. Data represent the mean + s.e.m. (n=10 larvae, 5–10 sections each). **** P<0.0001, unpaired t test. (G and H) 3 dpf miR-219 MO-injected larva has more PH3+ cells than a control larva. (I) Graph showing the number of spinal cord cells labeled with anti-PH3 antibody in control and miR-219 MO-injected larvae. Data represent the mean + s.e.m. (n = 10 sections obtained from 15 larvae per group, with two replicates). *P=0.0328, unpaired t test. (J–L) 3 dpf miR-219 MO injected larvae have more Sox2+ cells than control larvae. Boxed areas are shown at higher magnification in J’ and K’. Graph showing the number of Sox2+ cells in ventral, dorsal and entire spinal cord. Data in graph represent mean + s.e.m. (n = 10 sections obtained from 15 larvae per group, with three replicates). *P=0.0369, ****P<0.0001, unpaired t test. (J, K, M and N) 3 dpf miR-219 MO injected larvae maintain a primitive lumen marked by apically localized F-actin and ZO-1 (brackets). Scale bar equals 10 µm for low magnification images and 5 µm for high magnification images. See also Figure S1.

To test miR-219 function, we investigated markers of neural precursors in control larvae and larvae injected with antisense morpholino oligonucleotides (MO) (Zhao et al., 2010) designed to bind the mature form of miR-219, thereby blocking function. In 3 dpf control larvae, few spinal cord cells incorporated BrdU, indicating a low level of neural precursor division (Figure 2D). By contrast, numerous BrdU+ cells occupied the medial spinal cord of miR-219 MO-injected larvae (Figure 2E). Quantification revealed elevated number of BrdU+ cells in both dorsal and ventral spinal cord, with an approximately 2-fold greater increase in dorsal spinal cord than in ventral spinal cord (Figure 2F). Similarly, immunohistochemistry to detect phospho-histone H3 (PH3), which reveals cells in M phase, showed that miR-219 MO-injected larvae had substantially more PH3+ spinal cord cells than control larvae (Figure 2G–2I). These data indicate that miR-219 drives neural precursors from the cell cycle. To determine if neural cells retain other precursor characteristics in the absence of miR-219 function we investigated expression of Sox2 and localization of apically associated proteins. In 3 dpf control larvae, Sox2+ cells were primarily located around the central canal, revealed by F-actin labeling, in the ventral spinal cord (Figure 2J). In miR-219 MO-injected larvae, Sox2+ cells lined the entire dorsoventral axis of the medial spinal cord (Figure 2K). Quantification revealed that miR-219 MO-injected larvae had approximately 1.75-fold more Sox2+ cells than control larvae, but that the difference was limited to dorsal spinal cord (Figure 2L). Additionally, F-actin labeling revealed an enlarged lumen extending into dorsal spinal cord (Figures 2K and 2K’). Similarly, whereas ZO-1 was limited to membranes surrounding the central canal of 3 dpf control larvae (Figures 2M and 2M’), ZO-1 labeling was evident along the entire dorsoventral extent of an enlarged lumen of miR-219 MO-injected larvae (Figures 2N and 2N’). These phenotypic features are characteristic of early neural development. Therefore, loss of miR-219 function results in retention of embryonic spinal cord characteristics into post-embryonic, larval stage.

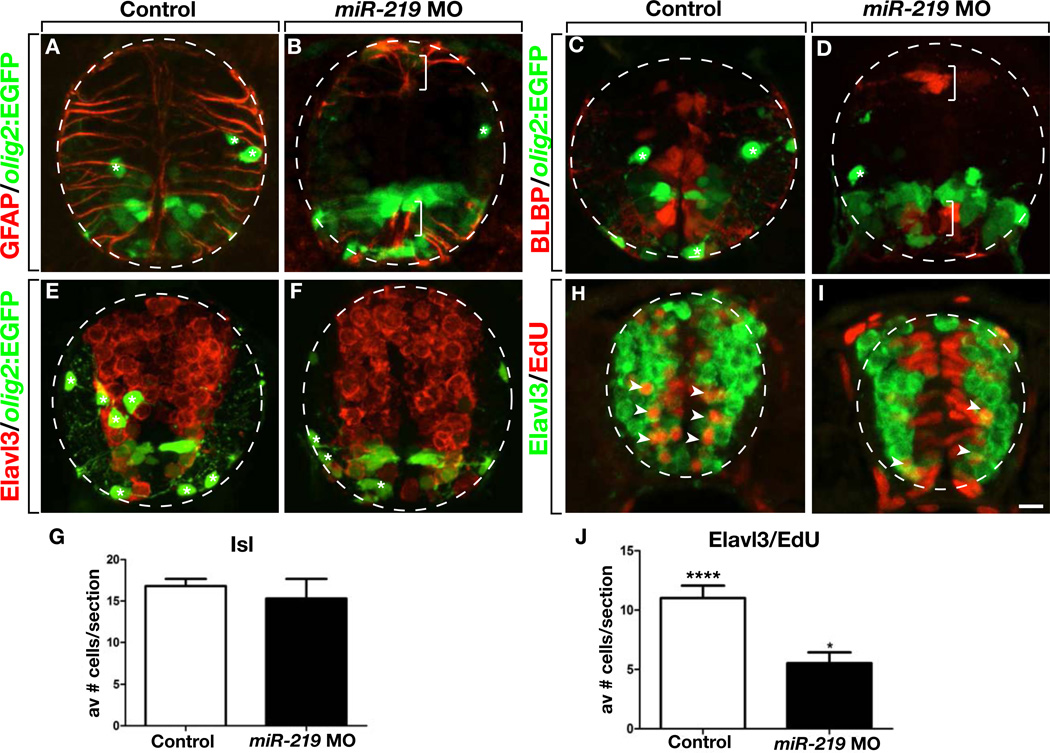

Our data show that larvae lacking miR-219 function maintain excess spinal cord precursors, raising the possibility that the OPC deficit we observed previously (Zhao et al., 2010) resulted from a failure of precursor differentiation. To test this, we examined radial glial and neuronal markers in combination with EGFP expression driven by an olig2:EGFP transgene, which marks pMN precursors, motor neurons and oligodendrocyte lineage cells (Shin et al., 2003). In wild-type zebrafish, radial glia appear by 1 dpf and persist throughout development and into adulthood (Park et al., 2007). Accordingly, numerous GFAP+ radial glia were evident in the spinal cords of 3 dpf control larvae (Figure 3A). By contrast, GFAP+ radial glia were completely absent from miR-219 MO-injected larvae, except in the most dorsal and ventral portions of the spinal cord (Figure 3B). Consistent with our previous results, miR-219 MO-injected larvae also had few OPCs. Expression of the radial glia marker BLBP showed a similar pattern, marking numerous cells in control larvae (Figure 3C), but only a few cells in the most dorsal and ventral portions of the spinal cord of miR-219 MO-injected larvae (Figure 3D). To investigate neuronal differentiation, we examined expression of Elavl3, which marks newly born neurons (Marusich et al., 1994). This revealed no obvious differences in neurons in wild-type and miR-219 MO-injected larvae (Figures 3E and 3F). To quantify a specific population of neurons we counted motor neurons, which are produced by ventral spinal cord precursors and marked by Islet (Isl) expression. Indeed, motor neuron number in miR-219 MO-injected larvae was not different from control at 3 dpf (Figure 3G). To investigate whether late stages of neurogenesis might be specifically affected by miR-219 loss of function, we performed a fate mapping experiment. In particular, we labeled dividing cells at 24 hours post fertilization (hpf) with a pulse of the thymidine analog EdU, waited 24 hours to permit cell differentiation and examined EdU distribution. In control embryos, many of the EdU+ cells were also Elavl3+, representing precursors that had left the cell cycle and differentiated as neurons (Figure 3G). By contrast, miR-219 MO-injected embryos retained most of the EdU label within the proliferative zone and had correspondingly few EdU+ Elav3+ neurons (Figure 3H). Quantification confirmed this, showing that miR-219 MO-injected embryos had approximately half as many EdU+ Elav3+ neurons as control embryos (Figure 3J). Together with the data presented above, these results indicate that miR-219 promotes exit of neural precursors from the cell cycle and their differentiation as neurons and glia at late stages of development.

Figure 3. miR-219 is Required for Differentiation of Glia and Late-born Neurons.

All images show representative transverse sections through trunk spinal cord with dorsal up. (A and B) Whereas numerous GFAP+ radial glia occupy the spinal cord of a 3 dpf control larva, a miR-219 MO-injected larva has few radial glia except for the most dorsal and ventral regions of spinal cord (brackets). Asterisks mark oligodendrocyte lineage cells. (C and D) Images showing a deficit of BLBP+ radial glia in a miR-219 MO-injected larva compared to control. (E and F) miR-219 MO-injected larvae appear to have a normal number and distribution of neurons, marked by Elavl3 expression, but fewer oligodendrocyte lineage cells (asterisks) than control larvae. (G) Graph showing number of Isl+ motor neurons in control and miR-219 MO-injected larvae. Data are presented as mean + s.e.m. (n = 10 sections obtained from 15 larvae per group, with two replicates). P>0.05, unpaired t test. (H and I) Confocal images and associated orthogonal projections of embryos pulsed with EdU at 1 dpf and fixed at 2 dpf Numerous Edu+ cells are also Elavl3+ (arrowheads) in control larvae (H) whereas most EdU label persists within cells lining the spinal cord lumen and fewer neurons are labeled by EdU in miR-219 MO-injected larva (I). Dashed lines indicate orthogonal section planes, showing co-localization of EdU and Elavl3. (J) Graph showing number of Elav3+ EdU+ neurons in control and miR-219 MO-injected larvae. Data represent mean + s.e.m. (n = 10 sections obtained from 5 larvae per group). ****P<0.0001, unpaired t test. Scale bar equals 10 µm.

miR-219 Regulates pard3 and prkci via 3’ UTR Target Sites

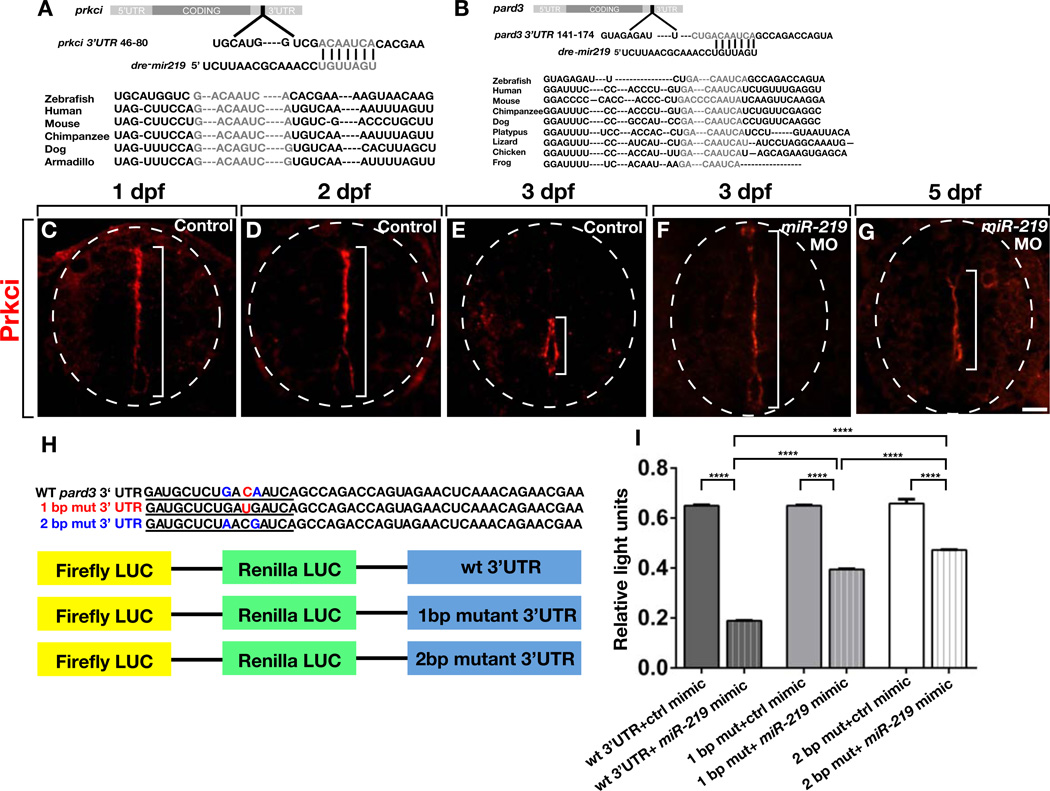

Because zebrafish larvae retain neuroepithelial precursor characteristics in the absence of miR-219 function we hypothesized that miR-219 promotes downregulation of factors necessary for maintaining precursors in an undifferentiated, dividing state. To search for such factors we used target prediction software to identify miR-219 binding sites. Strikingly, this revealed single putative target sites within the 3’ UTR sequences of the Par genes pard3 and prkci that are conserved among numerous vertebrate species (Figure 4A and 4B). Target prediction analysis also revealed single sites within the 3’ UTR sequences of pard6b and pard6ga but not those of pard6a and pard6gb. Because apical localization of Par proteins is a hallmark feature of neuroepithelial precursors and Par protein functions promote neural precursor self-renewal in flies and mice (Bultje et al., 2009; Rolls et al., 2003; Kuchinke et al., 1998; Lee et al., 2006; Costa et al., 2008), we chose pard3 and prkci for further investigation.

Figure 4. miR-219 has Single, Conserved Target Sites within prkci and pard3 3’ UTRs.

(A and B) Schematic representations of prkci and pard3 transcripts with predicted miR-219 target sites conserved among various species. (C–E) In controls at 1 and 2 dpf, Prkci protein is concentrated at apical membranes lining the primitive lumen but by 3 dpf Prkci is limited to the central canal (brackets). (F and G) Prkci labeling persists along a primitive lumen extending across the spinal cord dorsoventral axis in 3 dpf and 5 dpf miR-219 MO-injected larvae. (H) 220 bp sequences from the pard3 3’ UTR containing wild-type and mutated miR-219 target sites were cloned into dual luciferase vectors. (I) Quantification of light units revealed a miR-219-mediated reduction of reporter gene expression that was abrogated by one and two basepair mutations within the target site. Data represent + s.e.m. (3 independent experiments). Brackets indicate pairwise comparisons. ****P < 0.0001, unpaired t test. Scale bar equals 10 µm.

To investigate whether Par protein localization coincides with neural precursor state, we performed immunohistochemistry using an anti-Prkci antibody (Horne-Badovinac et al., 2001; Roberts and Appel, 2009). Similar to ZO-1 and F-actin, Prkci was enriched at apical membranes along the entire spinal cord dorsoventral axis at 1 and 2 dpf, but then limited to membranes lining the central canal by 3 dpf (Figures 4C–4E). By contrast, apical Prcki persisted throughout the spinal cord of miR-219 MO-injected larvae at 3 dpf and 5 dpf (Figures 4F and 4G). These data are consistent with the possibility that miR-219 promotes the disappearance of Prkci from differentiating neuroepithelial precursors with a concomitant loss of apical membrane characteristics.

We lack an antibody that reliably detects Pard3 protein in zebrafish tissue. Therefore, to test whether miR-219 can regulate pard3 expression, we cloned the pard3 3’ UTR sequence containing the predicted target site into a dual luciferase reporter plasmid (Figure 4H), co-transfected the construct into HEK293T cells with either a negative control mimic or miR-219 mimic and measured luciferase activity. The miR-219 mimic, but not the control mimic, reduced luciferase expression by 70% (Figure 4I). Introduction of one and two base mutations in the target site abrogated miR-219-mediated inhibition of luciferase expression (Figure 4I), indicating that miR-219 regulates pard3 expression by binding the predicted target site.

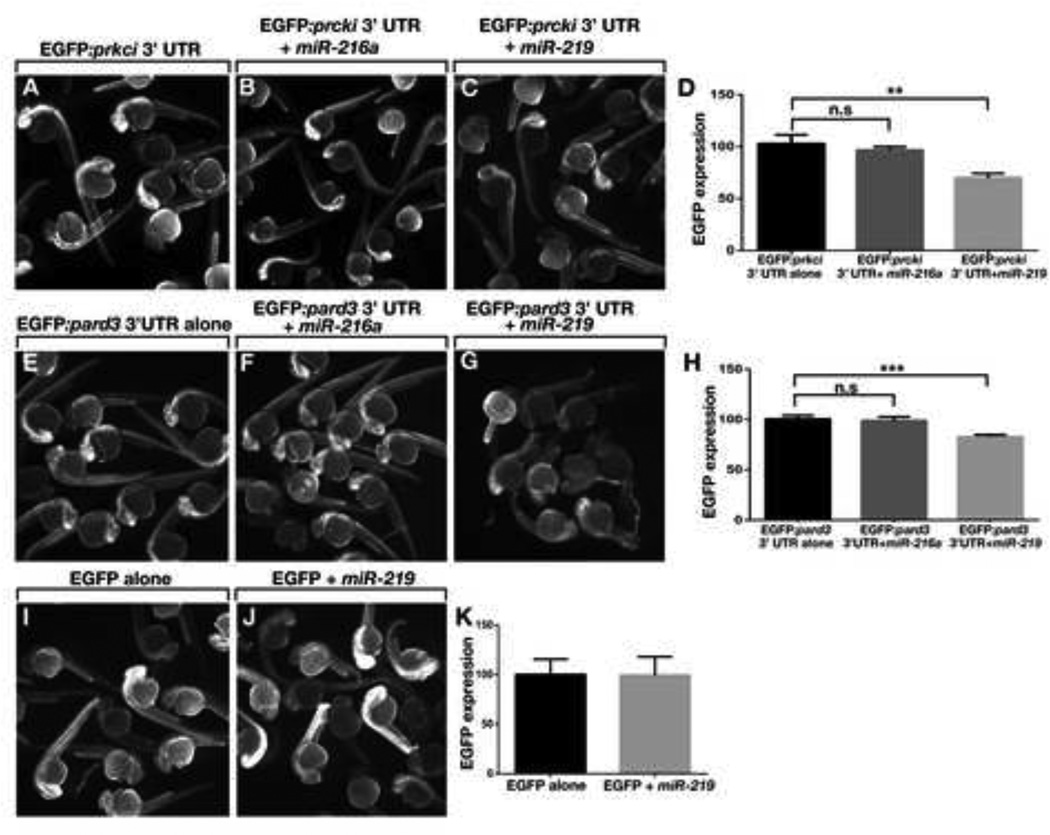

We tested the ability of mir-219 to regulate target expression in vivo by fusing the pard3 and prkci 3’ UTRs to cDNA encoding EGFP and using the constructs as templates for in vitro synthesis of mRNA, which we injected into zebrafish embryos at early cleavage stage. We co-injected some embryos with miR-219 or, as a control, miR-216a, which has no predicted target sites within the pard3 and prkci 3’ UTRs. To quantify EGFP expression, we measured fluorescence intensity within a defined region of the spinal cord. Whereas EGFP fluorescence appeared to be similar in embryos injected only with RNA including the prkci 3’ UTR and those co-injected with miR-216a, fluorescence intensity in embryos co-injected with miR-219 appeared to be less than control (Figures 5A–5C). Quantification confirmed this, revealing an approximately 30% reduction in fluorescence intensity in miR-219 injected embryos relative to the controls (Figure 5D). The pard3 3’ UTR mediated a similar effect (Figures 5E–5H), although the degree to which fluorescence intensity was reduced was less than that mediated by the prkci 3’ UTR. EGFP fluorescence produced by RNA having neither the pard3 nor prkci 3’ UTRs was not affected by co-injection of miR-219 (Figures 5I–5K).

Figure 5. mir-219 Regulates Reporter Gene Expression In Vivo via pard3 and prkci 3’ UTR Sequences.

(A–C) Fluorescence images of living embryos injected with EGFP:prkci 3’ UTR mRNA alone, miR-216a control or miR-219. (D) Graph showing EGFP fluorescence intensity values. Units represent pixel intensity and are reported as percent of control values (n = 20 embryos, with three replicates). Brackets indicate pairwise comparisons. **P=0.0014, unpaired t test. (E–G) Images of living embryos injected with EGFP:pard3 3’ UTR mRNA alone, miR-216a control or miR-219. (H) EGFP fluorescence intensity values shown as in D (n=20 embryos, with three replicates). ***P=0.0001 unpaired t test. (I and J) Images of embryos injected with EGFP mRNA alone or with miR-219. (K) EGFP fluorescence intensity values shown as in D (n = 20 embryos, with two replicates). P=0.8728, unpaired t test. Error bars represent + s.e.m.

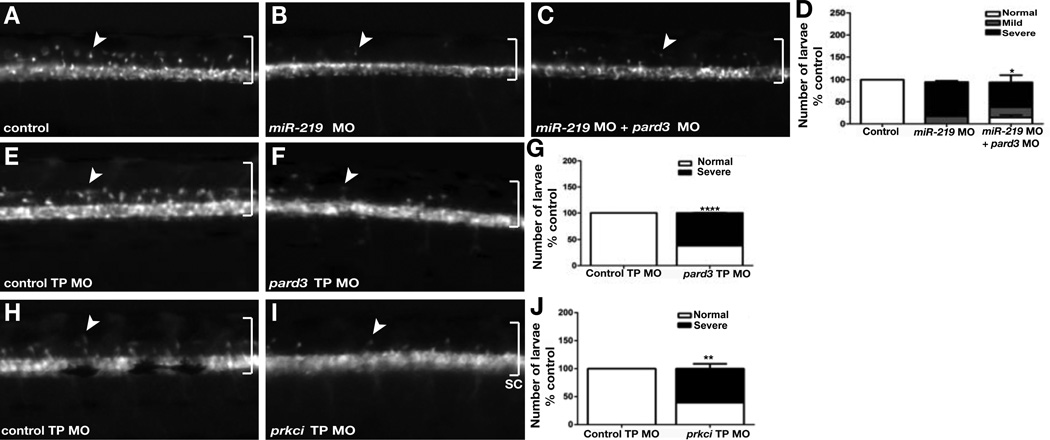

We next performed a series of experiments to investigate whether pard3 and prkci are functionally relevant, in vivo targets of miR-219. First, we reasoned that if the oligodendrocyte deficit of miR-219 MO-injected larvae results from elevated levels of Par proteins, then reduction of Par protein function should restore oligodendrocyte number. To test this prediction we assessed dorsally migrated oligodendrocytes, marked by Tg(olig2:EGFP) reporter expression, formed in larvae injected with only miR-219 MO or co-injected with miR-219 MO and MO designed to block translation of pard3 mRNA (Alexandre et al., 2010). Consistent with our previous observations, miR-219 MO-injected larvae had few dorsally migrated OPCs compared to control (Figures 6A and 6B). By contrast, co-injection of miR-219 MO and pard3 MO partially restored OPC number (Figure 6C). To quantify this effect, we classified phenotypes as normal, mild or severe based on the number of dorsally migrated OPCs. Whereas most larvae lacking only miR-219 function were classified as severe, significantly more larvae lacking both miR-219 and pard3 functions were classified as normal or mild, with a concomitant reduction of the severe class (Figure 6D). Therefore, reducing Pard3 function partially compensates for loss of miR-219 function, providing strong evidence that miR-219 regulates OPC formation by modulating Pard3 expression in vivo.

Figure 6. pard3 and prkci Are Functionally Relevant miR-219 Targets.

(A–C) Lateral images of living 3 dpf (Tg:olig2:EGFP) larvae, focused on the trunk spinal cord. Control larva, (A), shows the normal number and distribution of dorsally migrating OPCs (arrow). Whereas miR-219 MO-injected larvae have few OPCs (B), larvae co-injected with miR-219 and pard3 MOs have an intermediate number of OPCs (C). (D) Graph showing quantification of OPC phenotypic classes. Larvae classified as normal had the number of dorsally migrated OPCs typical of wild type. Larvae were classified as severe if fewer than 5 OPCs had migrated and mild in all other circumstances. P value was calculated by comparing the number of larvae with normal numbers of OPCs in the miR-219-MO alone and miR-219 MO + pard3 MO experiments. Data represent + s.e.m. (n = 25 larvae per group, with three replicates). *P=0.0324, unpaired t test. (E and F) Larvae injected with pard3 TP MO have fewer OPCs than those injected with a control TP MO. (G) Graph showing quantification of the pard3 TP MO phenotypes. Data represent + s.e.m. (n = 35 and 55 larvae in two independent experiments) ****P<0.0001, unpaired t test (H and I) Larvae injected with prkci TP MO have fewer OPCs than those injected with a control TP MO. (J) Graph showing quantification of the prkci TP MO phenotype. (n = 45–60 larvae per experiment, with three independent experiments). **P=0.0020, unpaired t test.

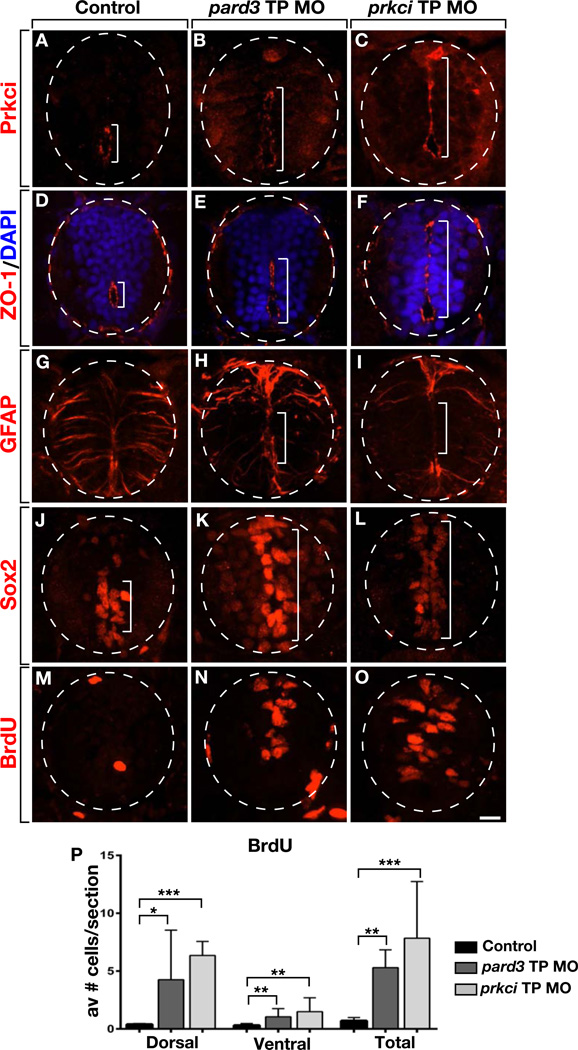

We also predicted that preventing the binding of endogenous miR-219 to its relevant target sites should cause a deficit of OPCs, similar to miR-219 knockdown. To test this we synthesized Target Protector (TP) MOs (Staton and Giraldez, 2011) designed to bind to and block the putative miR-219 target sites within the pard3 and prkci 3’ UTRs. We also synthesized a MO directed to a non-overlapping sequence within the pard3 3’ UTR to function as a control. Larvae injected with control TP MO were unaffected, forming the normal number of dorsally migrated OPCs (Figure 6E), but a significant number of pard3 TP MO-injected larvae had few OPCs (Figures 6F and 6G). Similarly, most prkci TP MO-injected larvae formed fewer OPCs than controls (Figures 6H–6J). To investigate whether the OPC deficit is linked to changes in the neural precursor population, we examined distribution of apical membrane associated proteins in TP injected larvae. 3 dpf larvae injected with either pard3 TP MO or prkci TP MO had expanded primitive lumens along which Prkci and ZO-1 were concentrated (Figures 7A–7F), phenocopying injection of miR-219 MO. TP MO-injected larvae also had fewer radial glia than controls (Figure 7G–7I). Furthermore, TP MO-injected larvae had more Sox2+ cells in dorsal spinal cord than controls (Figures 7J–7L) as well as more BrdU+ cells (Figures 7M–7O). Similarly to mir-219 MO, the increase in BrdU+ cells resulting from TP MO occurred mostly in dorsal spinal cord (Figure 7P). Therefore, blocking interaction of miR-219 with its pard3 and prkci target sites is sufficient to maintain embryonic spinal cord precursors and prevent formation of OPCs.

Figure 7. Blocking miR-219 access to pard3 or prkci 3’ UTRs phenocopies miR-219 loss of function.

All panels show representative images of spinal cord transverse sections with dorsal up. (A–C) 3 dpf larvae labeled to detect Prcki localization. In the control, Prkci is limited to a small central canal (A). By contrast, Prkci extends dorsally in pard3 TP MO and prkci TP MO injected larvae, marking a primitive lument (B and C). (D–F) Similarly to Prcki, ZO-1 is restricted to a central canal in the control larva (D) but extends more dorsally in pard3 TP MO and prkci TP MO injected larvae (E and F). (G–I) pard3 TP MO and prkci TP MO injected larvae have fewer medial spinal cord radial glia than control. (J–L) pard3 TP MO and prkci TP MO injected larvae have more Sox2+ cells in dorsal spinal cord than control. (M–O) BrdU incorporation at 3 dpf. TP MO-injected larvae have more labeled cells than control. (P) Graph showing number of BrdU+ cells in dorsal, ventral and entire spinal cord. Data represent + s.e.m. (n = 10 larvae for each experiment, 5–10 section per larva). *P<0.05, **P<0.005, ***P<0.0005, unpaired t test. Scale bar equals 10 µm. See also Figure S2.

Finally, we attempted to overexpress Pard3, predicting that it, also, would phenocopy mir-219 loss of function. To do so we used a transgenic line,Tg(hsp70l:pard3-EGFP), which expresses Pard3 fused to EGFP (Geldmacher-Voss et al., 2003) under control of a heat-responsive promoter. Although the fusion protein was evident in non-neural tissues following heat shock, it appeared to be rapidly degraded in the neural tube. Nevertheless, with repeated heat shocks we were able to obtain some embryos with fusion protein expression evident in the spinal cord. Notably, when present, EGFP was co-localized with ZO-1 to an expanded, primitive lumen (Figure S2), consistent with the idea that persistent Pard3 expression maintains spinal cord cells in a neuroepithlial precursor state. Therefore, we conclude that negative regulation of Pard3 and Prcki by miR-219 drives neural precursor differentiation at late embryonic stage.

DISCUSSION

The progression of neural precursors from symmetric proliferative to asymmetric self-renewing division and, subsequently, to symmetric cell cycle exit and differentiation represent key transitions in neural development. Data drawn from investigations of invertebrate and vertebrate neural precursors provide the basis for a model in which symmetric or asymmetric distribution of apical Par proteins to sibling cells at mitosis influences whether each remains as a precursor or enters a differentiation pathway (reviewed in Homem and Knoblich, 2012; Shitamukai and Matsuzaki, 2012; Huttner and Kosodo, 2005). Still missing from this model is a mechanism that would cause both progeny of a dividing precursor to leave behind the self-renewing activity of apical Par proteins and undergo differentiation. Here we propose that miRNA-mediated downregulation of Par proteins contributes to this transition.

In Drosophila, neuroblasts delaminate from the neuroectoderm, retaining an apicobasal polarity evident in asymmetric localization of Par proteins (reviewed in Homem and Knoblich, 2012). Apical Par proteins, through interaction with Inscutable, Gαi, Pins and Mud, position the mitotic spindle so that neuroblast division occurs perpendicularly to the plane of the neuroectoderm (reviewed in Siller and Doe, 2009). Consequently, apical Par proteins are retained within one progeny cell, which continues as a neuroblast, and absent from the other, which undergoes differentiation, indicating that apical proteins are associated with self-renewal. Consistent with this, reduction of aPKC function resulted in failure of neuroblasts to undergo self-renewing divisions whereas aPKC overexpression caused formation of excess neuroblasts (Lee et al., 2006; Haenfler et al., 2012). Neuroblasts exit the cell cycle prior to adulthood, under control of a temporally regulated sequence of transcription factors (Maurange et al., 2008), but whether apical Par proteins are downregulated to help promote this transition and the mechanisms by which this might occur remain unknown.

Although the correlation of spindle orientation, cleavage plane and cell fate are not as obvious in the vertebrate CNS as in flies, several studies provided evidence that vertical cleavage planes that bisect apical membrane of neural precursors equally are generally associated with symmetric proliferative divisions whereas oblique or horizontal cleavage planes that cause unequal segregation of apical membrane to progeny cells are asymmetric with respect to cell fate (Bultje et al., 2009; Kosodo et al., 2004; Haydar et al., 2003; Chenn and McConnell, 1995). Consistent with these observations, Pard3 can be asymmetrically localized to the progeny of dividing radial glial cells in mice, although the mechanism of unequal distribution was not clear (Bultje et al., 2009). Notably, whereas overexpression of Pard3 promoted symmetric divisions producing progenitor fate, Pard3 knockdown caused symmetric divisions producing neurons (Bultje et al., 2009). Similarly, Pard3 knockdown reduced proliferation of mouse cortical progenitors and favored formation of neurons whereas Pard3 or Pard6α overexpression drove progenitor proliferation (Costa et al., 2008). These observations support the idea that, like invertebrates, apically localized Par complex proteins promote a self-renewing precursor state in the vertebrate nervous system.

Birthdating studies showed that the majority of dividing cells within the mouse cerebral cortex ventricular zone exit the cell cycle and differentiate by the end of embryogenesis (Takahashi et al., 1996). This cessation of proliferation correlates temporally with depletion of apical Par complex proteins from the ventricular surface (Costa et al., 2008). We showed here that the zebrafish spinal cord undergoes a similar transition. During early stages of neural development, a primitive lumen occupies nearly the entire dorsoventral extent of the neural tube. Apically associated proteins, including the Par complex protein Prkci, are localized to cell membranes lining the ventricular surface of the lumen. Cells that border the lumen, and thereby have apically concentrated Par proteins, have precursor characteristics in that they divide and express the precursor marker Sox2. At the end of the embryonic period, the lumen transforms to a small central canal in the ventral spinal cord. Concomitantly, the apparent concentration of apically associated proteins is reduced from all spinal cord cells except those bordering the central canal and the number of dividing neural precursors is greatly diminished.

Our functional studies provide evidence that termination of neural precursor division and subsequent neuronal and glial differentiation at late embryonic stage is driven, in part, by negative regulation of Pard3 and Prkci by miR-219. We noted, though, that our functional manipulations affected primarily dorsal spinal cord. In fact, transitions in lumen morphogenesis, apical protein distribution and neural precursor characteristics during development occur predominantly in dorsal spinal cord. In ventral spinal cord, apical proteins and Sox2+, putative neural precursors that also express olig2 (Park et al., 2007) remain localized to the central canal into postembryonic stage, raising the possibility that ventral neural precursors are not subject to miR-219 regulation. However, most spinal cord OPCs arise from ventral cells that express olig2. Nevertheless, prkci mutant zebrafish larvae had excess OPCs (Roberts and Appel, 2009) and mir-219 knockdown larvae had a deficit of OPCs (Zhao et al., 2010). One possible explanation is that OPCs originate dorsal to the central canal from precursors that are regulated by miR-219. More careful fate-mapping of OPCs origins should resolve this question.

Our data now extend current models in which, during early stages of neural development, mechanisms that influence whether the progeny cells of dividing neural precursors receive equal or unequal amounts of apical Par proteins influence whether divisions are symmetric and proliferative or asymmetric with respect to cell fate. We now propose that, near the end of embryogenesis, inhibition of new Par protein translation by miR-219 depletes Par proteins from dividing precursors below a limit necessary for their self-renewing functions, causing precursors to exit the cell cycle and differentiate as late born neurons and glia.

Previous work identified miR-219 as an important regulator of oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination (Zhao et al., 2010; Dugas et al., 2010). Our study identifies an additional earlier and broader role for miR-219 in promoting the transition of neural precursors to specified cell types, including oligodendrocyte lineage cells. Additionally, because neural precursors continue to divide in the absence of miR-219 function, our data raise the possibility that alterations of miR-219 expression contribute to tumor formation. Consistent with this, miR-219 expression was significantly lower in childhood medulloblastoma relative to neural stem cells (Ferretti et al., 2009; Genovesi et al., 2011).

EXPERIMENTAL PROCEDURES

Zebrafish lines

The experiments conducted in this study used the following strains of zebrafish: AB, Tg(olig2:EGFP)vu12 (Shin et al., 2003) and Tg(hsp70l:pard3-EGFP)co14.

Immunohistochemistry

Immunohistochemistry was performed on frozen sections as described previously (Park et al., 2005). F-actin was labeled using Rhodamine Phalloidin (Invitrogen). To detect EdU incorporation, we used the EdU Detection Reaction mix (Invitrogen). Images were collected on a Zeiss Axio Observer microscope equipped with a PerkinElmer UltraVIEW VoX spinning disk confocal system and Volocity imaging software (PerkinElmer).

In situ RNA Hybridization

Antisense probes were transcribed using the Roche digoxigenin-labeling reagents and T3, T7, or SP6 RNA polymerases (New England Biolabs). To detect miR-219 expression, we used a dre-miR-219 miRCURY LNA probes (Exiqon 35172-01) (Kloosterman et al., 2006).

Luciferase Assay

A 220 bp sequence containing the predicted target site was placed in the 3’ UTR of a renilla luciferase reporter gene using the commercially available plasmid, psiCHECK-2 (Promega). This construct and microRNA mimics were co-transfected into HEK293T cells. Luciferase activity was detected using the SpectraMax L Luminescence microplate reader (Molecular Devices).

Morpholino Injections

Antisense morpholino oligonucleotides were purchased from Gene Tools, LLC. We injected 1–2 nl of 0.25 mM morpholino in injection buffer into the yolk just below the single cell of fertilized embryos. All morpholino oligonucleotide injected embryos were raised in embryo medium at 28.5°C.

BrdU and EdU Labeling

Dechorionated embryos were labeled with 20 mM 5-bromo-2′-deoxyuadine (BrdU) (Roche). For labeling with 5-ethynyl-2′-deoxyuridine (EdU), embryos were incubated in 2 mM EdU (Click-iT EdU Alexafluor 555 detection kit, Invitrogen #c10338).

GFP Injections and Quantification

1200 bp pard3 and 800bp prkci UTRs were cloned in a EGFP containing vector. These mRNAs were injected with or without miR-219 at one cell stage and raised to 30 hpf. Images of 20 embryos per group were collected using a Leica M165 FC microscope equipped with a SPOT RT3 camera and SPOT imaging software (Diagnostic Instruments Inc.). The experiment was performed three times and readings from 60 total embryos per group are reported.

Tg(hsp70l:pard3-EGFP) Construction and Heat Shock Procedure

53 hpf Tg(hsp70l:pard3-EGFP) and non-transgenic control embryos were placed in a 15mL conical tube in approximately 10mL of embryo medium and immersed in a 38°C water bath for one hour after which they were allowed to recover at RT for one hour.

Quantitative PCR

RNA was isolated from 15–20 pooled larvae for each control or experimental condition. Samples for each condition were collected in triplicate. Real time qPCR was performed in triplicate for each cDNA sample using an Applied Biosystems StepOne Plus machine and software version 2.1.

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

Cell counts were obtained by direct observation of sections using the microscopes described above. For Sox10, Sox2, PH-3 and Isl quantification, 10 sections per embryo from 15 embryos per group with two or three replicates were counted to produce the average number per section. P values were generated using an unpaired t-test using GraphPad Prism software. Dorsally migrated OPCs were assessed based on lateral views of Tg(olig2:EGFP) embryos at 3 dpf. olig2:EGFP positive cells were counted over the entire spinal cord. Larvae classified as normal had the number of dorsally migrated OPCs typical of wild type. Larvae were classified as severe if fewer than 5 OPCs had migrated and mild in all other circumstances. P values were generated using an unpaired t-test comparing the number of normal embryos when injected with miR-219 MO alone or miR-219 together with pard3 MO.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

miR-219 regulates neural precursor maintenance and specification

miR-219 inhibits expression of pard3 and prkci via 3’ UTR target sites

miR-219 reduction interferes with neuronal and glial cell differentiation

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank members of the Appel lab for valuable discussions and Jacob Hines and Macie Walker for comments on the manuscript. This work was supported by NIH grant RO1 NS40660 to B.A. and a gift from the Gates Frontiers Fund. L.I.H. was supported by Molecular Biology Program T32 GM008730. The University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus Zebrafish Core Facility is supported by NIH grant P30 NS048154. The anti-BrdU antibody, developed by S.J. Kaufman, and the anti-Isl antibody, developed by T.M. Jessell, were obtained from the Developmental Studies Hybridoma Bank developed under the auspices of the National Institute of Child Health and Human development and maintained by the University of Iowa, Department of Biological Sciences, Iowa City, IA. The luciferase experiments were performed in the laboratory of Lynne Bemis, who also provided important advice.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.I.H. performed all the experiments and acquired the data. A.J.B provided the transgenic line used to produce the data in Supplementary Figure S2. L.I.H. and B.A. conceived the project, analyzed data and wrote the paper.

COMPETING FINANCIAL INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing financial interests.

REFERENCES

- Alexandre P, Reugels AM, Barker D, Blanc E, Clarke JDW. Neurons derive from the more apical daughter in asymmetric divisions in the zebrafish neural tube. Nat Neurosci. 2010;13:673–679. doi: 10.1038/nn.2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Asuelime GE, Shi Y. The little molecules that could: a story about microRNAs in neural stem cells and neurogenesis. Front Neurosci. 2012;6:176. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2012.00176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bartel DP. MicroRNAs: target recognition and regulatory functions. Cell. 2009;136:215–233. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonev B, Pisco A, Papalopulu N. MicroRNA-9 reveals regional diversity of neural progenitors along the anterior-posterior axis. Dev Cell. 2011;20:19–32. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2010.11.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Böhme G. Formation of the central canal and dorsal glial septum in the spinal cord of the domestic cat. J. Anat. 1988;159:37–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bultje RS, Castaneda-Castellanos DR, Jan LY, Jan Y-N, Kriegstein AR, Shi S-H. Mammalian Par3 regulates progenitor cell asymmetric division via notch signaling in the developing neocortex. Neuron. 2009;63:189–202. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2009.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cheng L-C, Pastrana E, Tavazoie M, Doetsch F. miR-124 regulates adult neurogenesis in the subventricular zone stem cell niche. Nat Neurosci. 2009;12:399–408. doi: 10.1038/nn.2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chenn A, McConnell SK. Cleavage orientation and the asymmetric inheritance of Notch1 immunoreactivity in mammalian neurogenesis. Cell. 1995;82:631–641. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(95)90035-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coolen M, Thieffry D, Drivenes Ø, Becker TS, Bally-Cuif L. miR-9 Controls the Timing of Neurogenesis through the Direct Inhibition of Antagonistic Factors. Dev Cell. 2012;22:1052–1064. doi: 10.1016/j.devcel.2012.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Costa MR, Wen G, Lepier A, Schroeder T, Götz M. Par-complex proteins promote proliferative progenitor divisions in the developing mouse cerebral cortex. Development. 2008;135:11–22. doi: 10.1242/dev.009951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dong Z, Yang N, Yeo S-Y, Chitnis A, Guo S. Intralineage directional Notch signaling regulates self-renewal and differentiation of asymmetrically dividing radial glia. Neuron. 2012;74:65–78. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2012.01.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dugas JC, Cuellar TL, Scholze A, Ason B, Ibrahim A, Emery B, Zamanian JL, Foo LC, McManus MT, Barres BA. Dicer1 and miR-219 Are required for normal oligodendrocyte differentiation and myelination. Neuron. 2010;65:597–611. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.01.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ellis P, Fagan BM, Magness ST, Hutton S, Taranova O, Hayashi S, McMahon A, Rao M, Pevny L. SOX2, a persistent marker for multipotential neural stem cells derived from embryonic stem cells, the embryo or the adult. Dev Neurosci. 2004;26:148–165. doi: 10.1159/000082134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferretti E, De Smaele E, Po A, Di Marcotullio L, Tosi E, Espinola MSB, Di Rocco C, Riccardi R, Giangaspero F, Farcomeni A, et al. MicroRNA profiling in human medulloblastoma. Int. J. Cancer. 2009;124:568–577. doi: 10.1002/ijc.23948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fietz SA, Huttner WB. Cortical progenitor expansion, self-renewal and neurogenesis-a polarized perspective. Current opinion in neurobiology. 2011;21:23–35. doi: 10.1016/j.conb.2010.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geldmacher-Voss B, Reugels AM, Pauls S, Campos-Ortega JA. A 90-degree rotation of the mitotic spindle changes the orientation of mitoses of zebrafish neuroepithelial cells. Development. 2003;130:3767–3780. doi: 10.1242/dev.00603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Genovesi LA, Carter KW, Gottardo NG, Giles KM, Dallas PB. Integrated analysis of miRNA and mRNA expression in childhood medulloblastoma compared with neural stem cells. PLoS ONE. 2011;6:e23935. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0023935. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gönczy P. Mechanisms of asymmetric cell division: flies and worms pave the way. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2008;9:355–366. doi: 10.1038/nrm2388. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Götz M, Huttner WB. The cell biology of neurogenesis. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol. 2005;6:777–788. doi: 10.1038/nrm1739. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haenfler JM, Kuang C, Lee C-Y. Cortical aPKC kinase activity distinguishes neural stem cells from progenitor cells by ensuring asymmetric segregation of Numb. Dev Biol. 2012;365:219–228. doi: 10.1016/j.ydbio.2012.02.027. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haydar TF, Ang E, Rakic P. Mitotic spindle rotation and mode of cell division in the developing telencephalon. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003;100:2890–2895. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0437969100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Homem CCF, Knoblich JA. Drosophila neuroblasts: a model for stem cell biology. Development. 2012;139:4297–4310. doi: 10.1242/dev.080515. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horne-Badovinac S, Lin D, Waldron S, Schwarz M, Mbamalu G, Pawson T, Jan Y, Stainier DY, Abdelilah-Seyfried S. Positional cloning of heart and soul reveals multiple roles for PKC lambda in zebrafish organogenesis. Curr Biol. 2001;11:1492–1502. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(01)00458-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huttner WB, Kosodo Y. Symmetric versus asymmetric cell division during neurogenesis in the developing vertebrate central nervous system. Curr. Opin. Cell Biol. 2005;17:648–657. doi: 10.1016/j.ceb.2005.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kapsimali M, Kloosterman WP, de Bruijn E, Rosa F, Plasterk RHA, Wilson SW. MicroRNAs show a wide diversity of expression profiles in the developing and mature central nervous system. Genome Biol. 2007;8:R173. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-8-r173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kimmel CB, Ballard WW, Kimmel SR, Ullmann B, Schilling TF. Stages of embryonic development of the zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 1995;203:253–310. doi: 10.1002/aja.1002030302. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kloosterman WP, Wienholds E, de Bruijn E, Kauppinen S, Plasterk RHA. In situ detection of miRNAs in animal embryos using LNA-modified oligonucleotide probes. Nat. Methods. 2006;3:27–29. doi: 10.1038/nmeth843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kosodo Y, Röper K, Haubensak W, Marzesco A-M, Corbeil D, Huttner WB. Asymmetric distribution of the apical plasma membrane during neurogenic divisions of mammalian neuroepithelial cells. EMBO J. 2004;23:2314–2324. doi: 10.1038/sj.emboj.7600223. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchinke U, Grawe F, Knust E. Control of spindle orientation in Drosophila by the Par-3-related PDZ-domain protein Bazooka. Curr Biol. 1998;8:1357–1365. doi: 10.1016/s0960-9822(98)00016-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee C-Y, Robinson KJ, Doe CQ. Lgl, Pins and aPKC regulate neuroblast self-renewal versus differentiation. Nature. 2006;439:594–598. doi: 10.1038/nature04299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makeyev EV, Zhang J, Carrasco MA, Maniatis T. The MicroRNA miR-124 promotes neuronal differentiation by triggering brain-specific alternative pre-mRNA splicing. Mol Cell. 2007;27:435–448. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2007.07.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marusich MF, Furneaux HM, Henion PD, Weston JA. Hu neuronal proteins are expressed in proliferating neurogenic cells. J. Neurobiol. 1994;25:143–155. doi: 10.1002/neu.480250206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maurange C, Cheng L, Gould AP. Temporal transcription factors and their targets schedule the end of neural proliferation in Drosophila. Cell. 2008;133:891–902. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2008.03.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H-C, Shin J, Roberts RK, Appel B. An olig2 reporter gene marks oligodendrocyte precursors in the postembryonic spinal cord of zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2007;236:3402–3407. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park H-C, Boyce J, Shin J, Appel B. Oligodendrocyte specification in zebrafish requires notch-regulated cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor function. J Neurosci. 2005;25:6836–6844. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0981-05.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prehoda KE. Polarization of Drosophila neuroblasts during asymmetric division. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2009;1:a001388. doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a001388. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts RK, Appel B. Apical polarity protein PrkCi is necessary for maintenance of spinal cord precursors in zebrafish. Dev Dyn. 2009;238:1638–1648. doi: 10.1002/dvdy.21970. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls MM, Albertson R, Shih H-P, Lee C-Y, Doe CQ. Drosophila aPKC regulates cell polarity and cell proliferation in neuroblasts and epithelia. J Cell Biol. 2003;163:1089–1098. doi: 10.1083/jcb.200306079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sevc J, Daxnerová Z, Miklosová M. Role of radial glia in transformation of the primitive lumen to the central canal in the developing rat spinal cord. Cell. Mol. Neurobiol. 2009;29:927–936. doi: 10.1007/s10571-009-9377-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shibata M, Nakao H, Kiyonari H, Abe T, Aizawa S. MicroRNA-9 regulates neurogenesis in mouse telencephalon by targeting multiple transcription factors. J Neurosci. 2011;31:3407–3422. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.5085-10.2011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shin J, Park H-C, Topczewska JM, Mawdsley DJ, Appel B. Neural cell fate analysis in zebrafish using olig2 BAC transgenics. Methods Cell Sci. 2003;25:7–14. doi: 10.1023/B:MICS.0000006847.09037.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shitamukai A, Matsuzaki F. Control of asymmetric cell division of mammalian neural progenitors. Dev. Growth Differ. 2012;54:277–286. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-169X.2012.01345.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siller KH, Doe CQ. Spindle orientation during asymmetric cell division. Nat Cell Biol. 2009;11:365–374. doi: 10.1038/ncb0409-365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Staton AA, Giraldez AJ. Use of target protector morpholinos to analyze the physiological roles of specific miRNA-mRNA pairs in vivo. Nat Protoc. 2011;6:2035–2049. doi: 10.1038/nprot.2011.423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takahashi T, Nowakowski RS, Caviness VS. The leaving or Q fraction of the murine cerebral proliferative epithelium: a general model of neocortical neuronogenesis. J Neurosci. 1996;16:6183–6196. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.16-19-06183.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tan S-L, Ohtsuka T, González A, Kageyama R. MicroRNA9 regulates neural stem cell differentiation by controlling Hes1 expression dynamics in the developing brain. Genes Cells. 2012;17:952–961. doi: 10.1111/gtc.12009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tep C, Kim ML, Opincariu LI, Limpert AS, Chan JR, Appel B, Carter BD, Yoon SO. BDNF induces polarized signaling of small GTPase (Rac1) at the onset of Schwann cell myelination through partitioning-defective 3 (Par3) J Biol Chem. 2011 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.312736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao C, Sun G, Li S, Shi Y. A feedback regulatory loop involving microRNA-9 and nuclear receptor TLX in neural stem cell fate determination. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 2009;16:365–371. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1576. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhao X, He X, Han X, Yu Y, Ye F, Chen Y, Hoang T, Xu X, Mi Q-S, Xin M, et al. MicroRNA-mediated control of oligodendrocyte differentiation. Neuron. 2010;65:612–626. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2010.02.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.