Abstract

Objectives

We evaluated emergency department (ED) provider adherence to guidelines for concurrent HIV-sexually transmitted disease (STD) testing within an expanded HIV testing program and assessed demographic and clinical factors associated with concurrent HIV-STD testing.

Methods

We examined concurrent HIV-STD testing in a suburban academic ED with a targeted, expanded HIV testing program. Patients aged 18–64 years who were tested for syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia in 2009 were evaluated for concurrent HIV testing. We analyzed demographic and clinical factors associated with concurrent HIV-STD testing using multivariate logistic regression with a robust variance estimator or, where applicable, exact logistic regression.

Results

Only 28.3% of patients tested for syphilis, 3.8% tested for gonorrhea, and 3.8% tested for chlamydia were concurrently tested for HIV during an ED visit. Concurrent HIV-syphilis testing was more likely among younger patients aged 25–34 years (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.36, 95% confidence interval [CI] 0.78, 2.10) and patients with STD-related chief complaints at triage (AOR=11.47, 95% CI 5.49, 25.06). Concurrent HIV-gonorrhea/chlamydia testing was more likely among men (gonorrhea: AOR=3.98, 95% CI 2.25, 7.02; chlamydia: AOR=3.25, 95% CI 1.80, 5.86) and less likely among patients with STD-related chief complaints at triage (gonorrhea: AOR=0.31, 95% CI 0.13, 0.82; chlamydia: AOR=0.21, 95% CI 0.09, 0.50).

Conclusions

Concurrent HIV-STD testing in an academic ED remains low. Systematic interventions that remove the decision-making burden of ordering an HIV test from providers may increase HIV testing in this high-risk population of suspected STD patients.

Individuals with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) are at an increased risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) acquisition.1 Inflammatory STDs (e.g., gonorrhea and chlamydia) are associated with HIV viral shedding and releasing high concentrations of HIV.2,3 Viral shedding is observed in the ulcer exudates of syphilis patients; ulcers disrupt the mucosal membranes of the genital regions, thereby increasing the potential for STD and HIV transfer between sexual partners.2,4 These biological mechanisms could explain why both ulcerative and non-ulcerative STDs are associated with an increased risk of HIV seroconversion.1–3,5–7

In addition to biological factors, HIV and STDs share similar risk behaviors, including high-risk sexual behaviors and substance abuse.4 HIV-STD prevention efforts are an ideal target for program collaboration and service integration (PCSI) because of the overlap in these high-risk populations. When financial and personnel resources are limited, integrated prevention efforts have the potential to be high-yield and prevent disease transmission. In recognition of the importance of STD infection in HIV transmission, in 1987, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Public Health Service recommended that all people seeking treatment for an STD should be routinely tested for HIV.8 In 1998, the Advisory Committee for HIV and STD Prevention recommended the early detection and treatment of STDs as a prevention mechanism for HIV, and highlighted the importance of HIV testing for all people who attend STD clinics and seek STD treatment.4

Despite these recommendations, HIV testing of suspected or diagnosed STD patients remained low. Among Medicaid enrollees and privately insured people diagnosed with an STD, HIV testing ranged from 10% to 20%.9,10 Inadequate concurrent HIV-STD testing was also observed in emergency departments (EDs), ranging from 3% to 16%.11,12 Among adolescent ED patients diagnosed with an STD, HIV testing rates as low as 0.3% have been observed.13

Surveys of ED providers during the previous decade indicate that HIV testing of STD patients is not a priority in the ED. Although 55% of providers would warn STD patients of their HIV risk, only 10% routinely encouraged their patients to receive an HIV test during their ED visit.14 When given a clinical scenario that included a patient with STD symptoms, only 13% of ED providers would test the patient for HIV.15 Even with the introduction of improved testing technologies in more recent years, only 4% of academic EDs recommended HIV testing for patients presenting with uncomplicated STDs.16

Of the 1.2 million people living with HIV in the United States, 20% are unaware of their HIV infection.17 Transmission from people with undiagnosed HIV infection accounts for 50% of new HIV transmission events.18 Evidence of missed opportunities for HIV diagnosis in clinical settings led CDC, in 2006, to release revised recommendations to promote routine, opt-out HIV testing in all clinical settings.19,20 Despite these recommendations for routine HIV testing, many EDs instead adopted targeted HIV testing programs due to financial, personnel, and other logistical challenges.21–25

In June 2008, an academic ED in North Carolina began a targeted, expanded HIV testing program. This program included a guideline that ED providers offer opt-out HIV testing to all patients who may be infected with an STD, in addition to other symptom- and behavior-based indicators for HIV testing. Shortly after introducing this expanded HIV testing program, a syphilis outbreak with high HIV coinfection rates was observed in North Carolina. Reported syphilis cases increased 84% to nearly 1,000 cases in 2009; more than 35% of these syphilis cases were coinfected with HIV. Among male cases in this outbreak, HIV/syphilis coinfection reached nearly 45%.26

In this study, our primary objective was to evaluate ED provider adherence to guidelines for concurrent HIV-STD testing. Our secondary objective was to assess the demographic and clinical factors associated with concurrent HIV-STD testing.

METHODS

Setting

In June 2008, the Emergency Medicine Department and the Infectious Diseases Department at a suburban academic hospital system together implemented an expanded HIV testing program in the ED. This ED facility is a level-one trauma center with approximately 65,000 adult patient visits annually that supports an emergency medicine residency program. While the HIV and syphilis case rate in the hospital's county is moderate (HIV: 10.1 per 100,000 population; primary/early/latent syphilis: 63.5 per 100,000 population), the hospital borders a county with some of North Carolina's highest HIV/STD rates (HIV: 29.7 per 100,000 population; primary/early/latent syphilis: 208.0 per 100,000 population) and sees many patients from surrounding areas. General consent procedures for the hospital (including the ED) were revised in January 2008 to include HIV, allowing for opt-out HIV testing with verbal consent. The program was designed to use existing staff and infrastructure, so as to be sustainable without external funding. Blood-based HIV testing was conducted by existing ED providers.

Prior to program implementation, ED providers were notified of the revised CDC guidelines for HIV testing in health-care settings. HIV testing was recommended for patients for whom the standard medical history discovered symptoms of a sexually transmitted infection, HIV/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)-related illness, or HIV-related risk behavior. ED providers were not asked to conduct a risk assessment. A third-generation HIV-1/2 enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) was used for testing, and positive results were confirmed by Western blot. ELISA-negative samples were pooled for HIV ribonucleic acid testing to detect acute HIV infection. Infectious diseases clinic providers were responsible for offering posttest counseling, notifying patients with positive results, and linking infected patients to HIV care. Posttest counseling for HIV-negative patients was available on a walk-in basis in the infectious diseases clinic at no charge.

Study population

This analysis included all patients aged 18–64 years who were tested for syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia from January 1 through December 31, 2009. Previously known HIV-positive patients (n=62), determined via medical record review, were excluded. As per the program's protocol, any patient tested for HIV in the study hospital within six months of their ED visit was also excluded (n=25). Patients tested for an STD as part of a standard organ-transplant screen (n=155) were not included in the expanded HIV testing program and were, therefore, excluded from this study.

Analysis

All data were collected via abstraction from ED medical records. The outcome of interest in this analysis was concurrent HIV-STD testing, defined as an HIV test ordered at the same ED visit as an STD diagnostic test. All laboratory data were collected from the hospital laboratory database.

We evaluated demographic and clinical factors for their association with concurrent HIV-STD testing. Demographic factors included sex (male or female), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic white, non-Hispanic black, Hispanic, or other), and age (18–24, 25–34, 35–44, 45–54, and 55–64 years of age).

Clinical factors included the patient's chief complaint at triage, acuity level at triage, and disposition. Patient chief complaint at triage was based on a text field completed when the patient enters the ED, prior to contact with any ED provider. This variable was grouped into four STD-focused categories: directly STD-related (genitourinary complaints, rash/skin issues, STD exposure, sexual assault, or substance abuse), potentially STD-related (abdominal pain, nausea/vomiting/diarrhea, psychological issues, or fever/flulike symptoms), pregnancy-related, or unrelated (chest pain, cerebrovascular complaints, headache, weakness, or other complaints). Acuity level at triage was measured by the Emergency Severity Index (ESI), a standardized five-level triage scale.27,28 The ESI was collapsed into a three-level variable for this analysis, where most severe = ESI levels 1 and 2, moderately severe = ESI level 3, and least severe = ESI levels 4 and 5. Disposition captured whether the patient was admitted or discharged after the ED visit.

Statistical methods

Results were a priori stratified by type of STD test ordered (syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia). Therefore, the unit of analysis was the individual STD test ordered and not the individual patient visit. The outcomes were the proportion of patients receiving an STD test who were concurrently tested for HIV and the corresponding 95% confidence interval (CI) (primary outcome: among all patients; secondary outcome: among patients testing STD-positive).

We used multivariate logistic regression to assess demographic and clinical factors associated with concurrent HIV-STD testing. Robust variance estimators accounted for potentially correlated observations in patients who were tested multiple times during the study period. If the multivariate logistic regression models did not converge due to small sample size or zero cell counts, multivariate exact logistic regression was used. Covariates were selected for inclusion in the final multivariate models via backwards elimination, with a change-in-estimate criteria of 10%.

Sensitivity analyses explored the inclusion of additional patient age ranges (13–17 and >64 years of age). Alternate categorizations of patients' chief complaints were also explored. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS® version 9.2.29

RESULTS

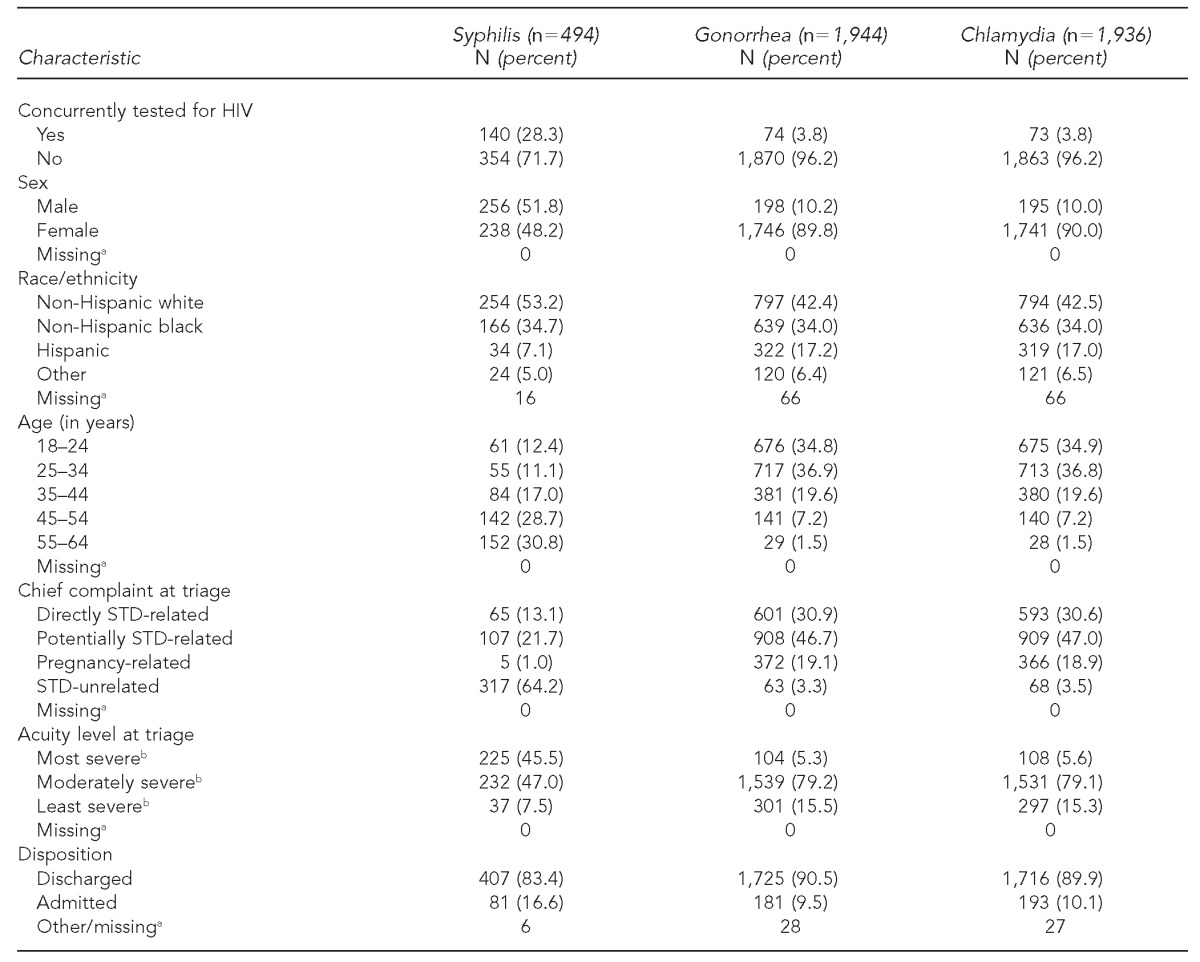

There were 2,395 patient visits in which an ED physician ordered an STD test, including 494 syphilis tests, 1,944 gonorrhea tests, and 1,936 chlamydia tests (Table 1). During this time period, 588 HIV tests were performed (data not shown).

Table 1.

Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients tested for STDs in a suburban emergency department in North Carolina, 2009

aThe number of patients missing demographic and clinical characteristics is presented for informational purposes only. As these patients were excluded from multivariate regression analysis, they do not contribute to the proportions presented in this table.

bThe ESI is a standardized five-level triage scale that was collapsed into a three-level variable for this analysis, where 1 and 2 = most severe, 3 = moderately severe, and 4 and 5 = least severe. Gilboy N, Tanabe T, Travers D, Rosenau AM. Emergency Severity Index (ESI): a triage tool for emergency department care, Version 4. Implementation handbook, 2012 ed. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0014. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011.

STD = sexually transmitted disease

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

ESI = Emergency Severity Index

Patients tested for gonorrhea and chlamydia were nearly all female (89.8% and 90.0%, respectively); 48.2% of patients tested for syphilis were female. Patients tested for gonorrhea and chlamydia tended to be younger than patients tested for syphilis; 71.7% of those tested for gonorrhea and chlamydia were 18–34 years of age vs. 23.5% of those tested for syphilis. The majority of patients tested for syphilis presented with symptoms unrelated to STD infection (64.2%), while almost all patients tested for gonorrhea (96.7%) and chlamydia (96.5%) presented with either directly or potentially STD-related symptoms. Nearly half (45.5%) of patients tested for syphilis presented with the highest acuity level at triage, while only 5.3% of patients tested for gonorrhea and 5.6% of patients tested for chlamydia were considered similarly as severe at triage (Table 1).

Patients tested for syphilis

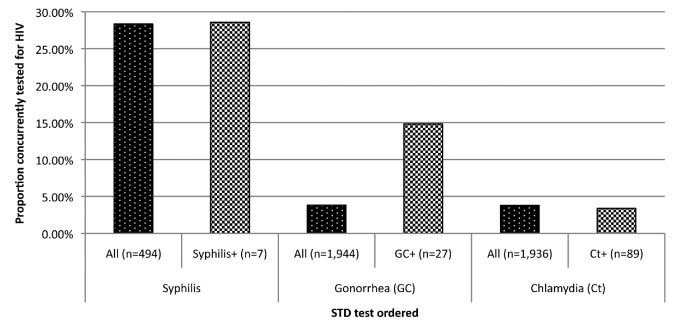

Nearly one-third (n=140/494, 28.3%) of patients tested for syphilis were concurrently tested for HIV in the ED (Table 1). Seven positive syphilis tests were detected (1.4% positivity), of which two were concurrently tested for HIV (Figure).

Figure.

Concurrent HIV-STD testing for all patients tested for STDs and STD-positive patients in a suburban emergency department in North Carolina, 2009a

aConcurrent HIV screening among all people tested for an STD was lacking (dark bars). Only 28.3%, 3.8%, and 3.8% of patients tested for syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia, respectively, were concurrently tested for HIV. Patients who tested positive for syphilis or chlamydia were no more or less likely to have a concurrent HIV test than all patients tested for syphilis or chlamydia (light bars). Patients who tested positive for gonorrhea were more likely to have a concurrent HIV test than all patients tested for gonorrhea (14.8% vs. 3.8%).

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

STD = sexually transmitted disease

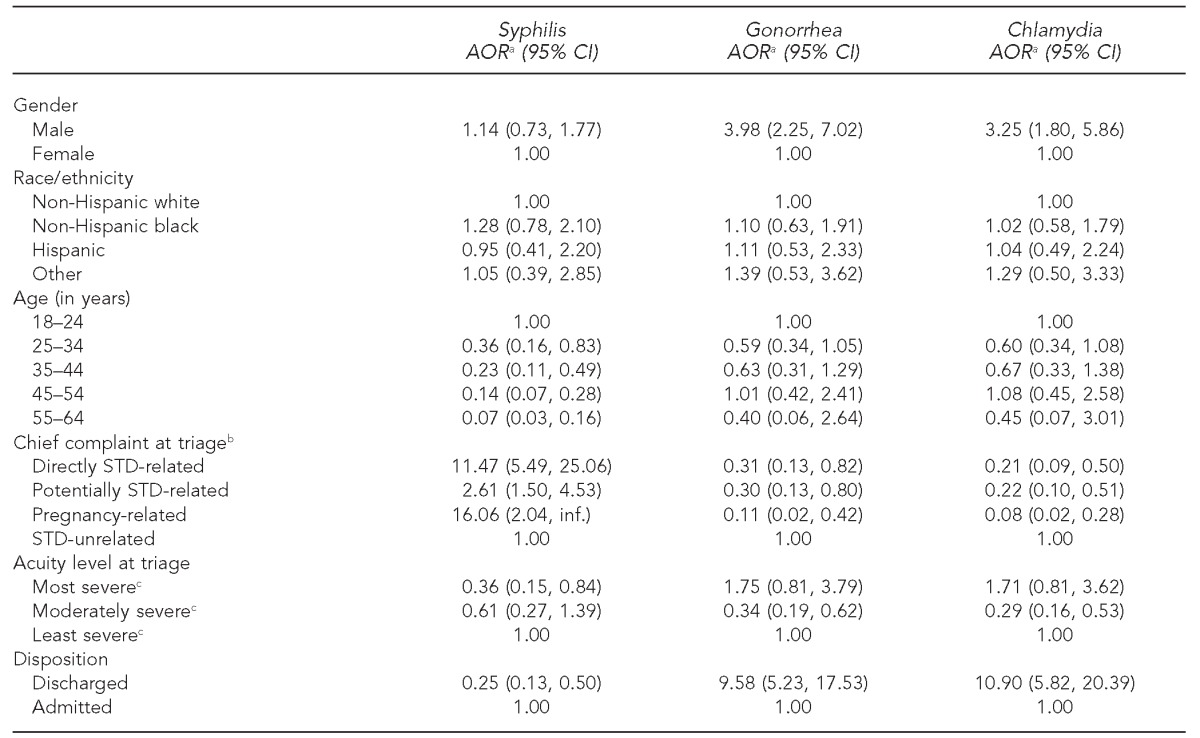

Younger patients tested for syphilis were more likely to receive a concurrent HIV test than older patients (Table 2). No other demographic characteristics were associated with concurrent HIV testing.

Table 2.

Demographic and clinical factors associated with concurrent HIV testing among patients tested for STDs in a suburban emergency department in North Carolina, 2009

aAll measures adjusted for gender, race/ethnicity, and age

bExact logistic regression used for these estimates due to small numbers and/or zero cell counts

cThe Emergency Severity Index is a standardized five-level triage scale that was collapsed into a three-level variable for this analysis, where 1 and 2 = most severe, 3 = moderately severe, and 4 and 5 = least severe. Gilboy N, Tanabe T, Travers D, Rosenau AM. Emergency Severity Index (ESI): a triage tool for emergency department care, Version 4. Implementation handbook, 2012 ed. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0014. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

STD = sexually transmitted disease

AOR = adjusted odds ratio

CI = confidence interval

Inf. = infinity

Patients tested for syphilis presenting with any STD-related condition were more likely to receive a concurrent HIV test than those presenting with unrelated conditions. All five pregnant women who were tested for syphilis were tested for HIV. Patients who presented with the most severe conditions at triage were less likely (adjusted odds ratio [AOR] = 0.36, 95% CI 0.15, 0.84) to receive an HIV test than patients presenting with the least severe conditions. Those who were discharged after their ED visit were less likely (AOR=0.25, 95% CI 0.13, 0.50) to receive an HIV test than those who were admitted (Table 2).

Patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia

Less than 4% of patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia were concurrently tested for HIV in the ED (gonorrhea: n=74/1,944, 3.8%; chlamydia: n=73/1,936, 3.8%) (Table 1). Twenty-seven patients tested positive for gonorrhea (1.4% positivity) and 89 patients tested positive for chlamydia (4.6% positivity)(Figure). Concurrent HIV testing was more frequent for gonorrhea-positive patients (n=4/27, 14.8%). No patients were coinfected with HIV and gonorrhea/chlamydia (data not shown).

Male patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia were more likely to have a concurrent HIV test than females (gonorrhea: AOR=3.98, 95% CI 2.25, 7.02; chlamydia: AOR=3.25, 95% CI 1.80, 5.86) (Table 2). No other demographic factors were associated with concurrent HIV-STD testing.

Patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia who presented with any level of STD-related complaint were less likely to receive a concurrent HIV test than those who presented with unrelated conditions. Women presenting with pregnancy-related complaints were the least likely to receive a concurrent HIV test (gonorrhea: AOR=0.11, 95% CI 0.02, 0.42; chlamydia: AOR=0.08, 95% CI 0.02, 0.28). Patients who presented with moderately severe conditions were less likely to receive a concurrent HIV test than those presenting with less severe conditions (gonorrhea: AOR=0.34, 95% CI 0.19, 0.62; chlamydia: AOR=0.29, 95% CI 0.16, 0.53). People who were discharged after their ED visit were more likely to have a concurrent HIV test than patients who were admitted (gonorrhea: AOR=9.58, 95% CI 5.23, 17.53; chlamydia: AOR=10.90, 95% CI 5.82, 20.39]) (Table 2).

Sensitivity analyses

Alternate inclusion criteria were explored in a sensitivity analysis: people aged 13–64 years, 18–≥65 years, and 13–≥65 years. None of the results differed when these younger and/or older age groups were included. Alternate categorizations of patient chief complaint at triage were also explored and did not yield significantly different results.

DISCUSSION

Despite the close interaction between HIV and STD transmission and the presence of an ED-based HIV testing program that specifically targeted suspected STD patients, concurrent HIV-STD testing was inadequate. Less than 30% of patients tested for syphilis and less than 4% of patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia were concurrently tested for HIV. In particular, HIV testing of older patients tested for syphilis and male patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia was low.

Measuring the success of a targeted HIV testing program is difficult when the denominator of patients to be tested is unclear. However, evaluating concurrent HIV-STD testing can be accomplished with existing laboratory data. In this analysis, we identified a measurable outcome of program success in a high-risk population: concurrent HIV-STD testing at a single ED visit. Improvements in concurrent HIV-STD testing through PCSI will hopefully interrupt disease transmission.

Low concurrent HIV-STD testing could be attributed in part to the independence given to ED providers. The ED providers were responsible for identifying individual patients to target for HIV testing. ED providers are trained to focus on the acute life- or limb-threatening problem that brought the patient to the ED. Preventive services, such as HIV testing, may not be a priority. Although ED providers were informed of the key target populations for the HIV testing program and of the rise in syphilis cases in 2009, continued educational campaigns to emphasize concurrent HIV-STD testing and the syphilis outbreak were not implemented during the time frame of this analysis. Further, practitioners in EDs may lack awareness of the close interrelationship between HIV and STDs.

Although concurrent HIV-STD testing was inadequate for all studied STDs, HIV testing among patients tested for syphilis was more successful than among patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia. The comparatively high rate of HIV testing among patients tested for syphilis could be attributed to the close link between HIV and syphilis, as well as the presence of the syphilis outbreak in North Carolina during the study period, including in the ED's catchment area. ED patients may be tested for syphilis due to the presence of particular risk factors or, as our data indicate, an STD-related symptom.

The urine-based gonorrhea/chlamydia diagnostic tests may result in low HIV testing if a blood sample is not drawn for other reasons. The number of patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia who had blood drawn in the ED was unavailable. Additionally, patients tested for gonorrhea/chlamydia may capture a broader cross-section of the ED population, including patients complaining of general abdominal pain and/or pregnancy-related complaints. The perceived link between general abdominal pain and/or pregnancy-related complaints and HIV/STDs may be weaker than the perceived link between a genital rash and HIV/STDs. Patients presenting with pregnancy-related complaints may be more likely to be engaged in regular medical care than other patients. Because HIV testing is a standard part of prenatal care, providers may not perceive as great a need for ED HIV screening.

Our results showing inadequate concurrent HIV-STD testing in an ED population are congruent with similar analyses conducted prior to the introduction of the 2006 CDC recommendations for routine HIV screening. Despite the public focus on and awareness of expanded HIV testing with the 2006 CDC recommendations and the presence of our own targeted, expanded HIV testing program, our data indicate that key, high-risk populations are still not adequately tested for HIV.

The stagnancy of concurrent HIV-STD testing over time could be attributed to a shift in focus from testing high-risk patients in high-prevalence clinical settings (e.g., STD clinics and prisons) to expanded HIV screening in all clinical settings. High-risk patients in more general clinical settings, such as suspected STD patients in EDs, may have been overlooked during both of these periods. Before the revised CDC recommendations, very few EDs promoted HIV testing for any patients other than those with clear AIDS-defining illness.14–16 After the 2006 CDC recommendations, EDs were encouraged to implement routine HIV screening in an effort to disassociate HIV from stigmatized high-risk behaviors.20 In practice, routine HIV screening may be realistically implemented as a convenience HIV testing protocol for all ED patients only on certain days or during certain time periods, based on availability of testing staff.30–38 Attempts to routinize testing, therefore, may have had the unintended consequence of neglecting to consistently provide HIV testing for a high-risk population.

The HIV testing program was specifically designed to function without external support and to use existing infrastructure and staff. However, the program evaluation component of this expanded HIV testing program is supported by dedicated funds that currently provide delivery of results in the University of North Carolina infectious diseases clinic at no charge to patients and fund personnel for program evaluation. If this funding decreases, the continued evaluation of program improvements will be in jeopardy, thereby hampering our ability to assess the HIV testing program for this at-risk population and coordinate further collaborative HIV-STD prevention efforts.

Limitations

Limitations of this analysis arose from the restrictions of the available data source. Hospital electronic medical records only provide information regarding health-care access at our clinical facility. It is unknown if patients sought recent HIV- or STD-related testing or medical care at another clinical facility. Data were not linked to the North Carolina surveillance database; therefore, we were unable to confirm the self-reported HIV-positive status of patients.

Our analysis also did not distinguish between patients who refused HIV testing and those who were not concurrently tested for HIV. Patient refusal of HIV testing was not routinely collected in the electronic medical record. We do not believe that our results were biased on HIV test refusal; less than 3% of the study population had documentation of HIV test refusal (syphilis: 0.2%; gonorrhea/chlamydia: 2.8%). ED patients may refuse HIV testing for any number of reasons, including recent HIV testing, low perceived HIV risk, lack of knowledge, fear of HIV testing, or a desire to focus on their acute health matter.33,36,39–43 Additionally, because blood-based diagnostic tests were used, patients who did not require a blood draw for other clinical reasons may have refused HIV testing. Patient educational campaigns and the systematic routinization of HIV testing for suspected STD patients may have increased patient acceptance of HIV testing. The small number of patients concurrently tested for HIV yielded imprecise effect estimates that may be exaggerated. However, the observed associations are so strong that mild attenuation would not change the interpretation of the results.

CONCLUSIONS

Implementation of an expanded HIV testing program in an ED setting is a complex undertaking. In this testing program, a large proportion of patients who should have been targeted were not tested. We recognize the potential limitations of targeted HIV testing, including patients with asymptomatic HIV or STD infection, patients who do not disclose their risky behaviors, and provider barriers to HIV testing. However, rather than transition to a routine HIV testing model, we remain committed to the concept of targeted testing, so as to prioritize our testing resources for suspected STD patients who participate in high-risk sexual behaviors. We plan to remove provider barriers to concurrent HIV-STD testing and limitations of patient risk disclosure by focusing on systematic changes that lessen the decision-making burden on ED providers. To improve upon our current targeted testing strategy, reflexive HIV testing for all patients in the ED who are tested for syphilis, gonorrhea, or chlamydia will be introduced. Patients will be notified of this reflexive testing and will have the opportunity to refuse HIV testing. This systematic change will be accompanied by an updated educational campaign for all ED providers and staff members to increase awareness of the interrelationship between HIV and STDs.

All patients evaluated for an STD should receive a concurrent HIV test. Despite the presence of CDC recommendations for routine HIV screening and a targeted HIV testing program, concurrent HIV-STD testing in the ED remains inadequately low. The relationship between HIV and syphilis appears to be better understood by ED providers than the relationship between HIV and gonorrhea/chlamydia. Systematic changes, such as reflexive HIV testing for all patients receiving an STD test, may remove ED provider barriers and increase concurrent HIV-STD testing in this high-risk population.

Footnotes

The authors thank the following individuals for their assistance in this research: Brooke Hoots, Janet Young, and Peter Gilligan for irreplaceable assistance in the design and initial implementation of the expanded human immunodeficiency virus testing program; Sergio Rabinovich and Bill Learning for facilitating data acquisition; Evelyn Foust, Jacquelyn Clymore, and Aaron Fleischauer for manuscript review; and Jan Scott, Pete Moore, and Lynne Sampson for funding and programmatic support.

Funding for this research came from grants PS #07-768, PS #10-10138, and PS #12-1201 from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Klein is also supported by a National Institutes of Health institutional predoctoral training grant (T32A1070114-06).

This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Office of Human Ethics Research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sexton J, Garnett G, Røttingen JA. Metaanalysis and metaregression in interpreting study variability in the impact of sexually transmitted diseases on susceptibility to HIV infection. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:351–7. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000154504.54686.d1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Fleming DT, Wasserheit JN. From epidemiological synergy to public health policy and practice: the contribution of other sexually transmitted diseases to sexual transmission of HIV infection. Sex Transm Infect. 1999;75:3–17. doi: 10.1136/sti.75.1.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kassler WJ, Zenilman JM, Erickson B, Fox R, Peterman TA, Hook EW., 3rd Seroconversion in patients attending sexually transmitted disease clinics. AIDS. 1994;8:351–5. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199403000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.HIV prevention through early detection and treatment of other sexually transmitted diseases—United States. Recommendations of the Advisory Committee for HIV and STD Prevention. MMWR Recomm Rep. 1998;47(RR-12):1–24. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cameron DW, Simonsen JN, D'Costa LJ, Ronald AR, Maitha GM, Gakinya MN, et al. Female to male transmission of human immunodeficiency virus type 1: risk factors for seroconversion in men. Lancet. 1989;2:403–7. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(89)90589-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Otten MW, Jr, Zaidi AA, Peterman TA, Rolfs RT, Witte JJ. High rate of HIV seroconversion among patients attending urban sexually transmitted disease clinics. AIDS. 1994;8:549–53. doi: 10.1097/00002030-199404000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Telzak EE, Chiasson MA, Bevier PJ, Stoneburner RL, Castro KG, Jaffe HW. HIV-1 seroconversion in patients with and without genital ulcer disease. A prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 1993;119:1181–6. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-119-12-199312150-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Public Health Service guidelines for counseling and antibody testing to prevent HIV infection and AIDS. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1987;36(31):509–15. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rust G, Minor P, Jordan N, Mayberry R, Satcher D. Do clinicians screen Medicaid patients for syphilis or HIV when they diagnose other sexually transmitted diseases? Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30:723–7. doi: 10.1097/01.OLQ.0000078652.66397.4C. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Tao G, Zhang CX. HIV testing of commercially insured patients diagnosed with sexually transmitted diseases. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:43–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318148c35a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Merchant RC, Catanzaro BM. HIV testing in US EDs, 1993–2004. Am J Emerg Med. 2009;27:868–74. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2008.06.019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Merchant RC, Depalo DM, Stein MD, Rich JD. Adequacy of testing, empiric treatment, and referral for adult male emergency department patients with possible chlamydia and/or gonorrhoea urethritis. Int J STD AIDS. 2009;20:534–9. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2008.008395. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Beckmann KR, Melzer-Lange MD, Gorelick MH. Emergency department management of sexually transmitted infections in US adolescents: results from the National Hospital Ambulatory Medical Care Survey. Ann Emerg Med. 2004;43:333–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2003.10.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Fincher-Mergi M, Cartone KJ, Mischler J, Pasieka P, Lerner EB, Billittier AJ., 4th Assessment of emergency department health care professionals' behaviors regarding HIV testing and referral for patients with STDs. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2002;16:549–53. doi: 10.1089/108729102761041100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wilson SR, Mitchell C, Bradbury DR, Chavez J. Testing for HIV: current practices in the academic ED. Am J Emerg Med. 1999;17:354–6. doi: 10.1016/s0735-6757(99)90085-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ehrenkranz PD, Ahn CJ, Metlay JP, Camargo CA, Jr, Holmes WC, Rothman R. Availability of rapid human immunodeficiency virus testing in academic emergency departments. Acad Emerg Med. 2008;15:144–50. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2008.00028.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, Del Rio C, Burman WJ. The spectrum of engagement in HIV care and its relevance to test-and-treat strategies for prevention of HIV infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52:793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marks G, Crepaz N, Janssen RS. Estimating sexual transmission of HIV from persons aware and unaware that they are infected with the virus in the USA. AIDS. 2006;20:1447–50. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000233579.79714.8d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Missed opportunities for earlier diagnosis of HIV infection—South Carolina, 1997–2005. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2006;55(47):1269–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Branson BM, Handsfield HH, Lampe MA, Janssen RS, Taylor AW, Lyss SB, et al. Revised recommendations for HIV testing of adults, adolescents, and pregnant women in health-care settings. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2006;55(RR14):1–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rothman RE, Hsieh YH, Harvey L, Connell S, Lindsell CJ, Haukoos J, et al. 2009 US emergency department HIV testing practices. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kelen GD, Rothman RE. Emergency department-based HIV testing: too little, but not too late. Ann Emerg Med. 2009;54:65–71. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2009.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.White DA, Cheung PT, Scribner AN, Frazee BW. A comparision of HIV testing in the emergency department and urgent care. J Emerg Med. 2010;39:521–8. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.04.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Arbelaez C, Block B, Losina E, Wright EA, Reichmann WM, Mikulinsky R, et al. Rapid HIV testing program implementation: lessons from the emergency department. Int J Emerg Med. 2009;2:187–94. doi: 10.1007/s12245-009-0123-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Arbelaez C, Wright EA, Losina E, Millen JC, Kimmel S, Dooley M, et al. Emergency provider attitudes and barriers to universal HIV testing in the emergency department. J Emerg Med. 2012;42:7–14. doi: 10.1016/j.jemermed.2009.07.038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, Communicable Disease Surveillance Unit. North Carolina special report: syphilis morbidity 2009. Raleigh (NC): North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wuerz RC, Milne LW, Eitel DR, Travers D, Gilboy N. Reliability and validity of a new five-level triage instrument. Acad Emerg Med. 2000;7:236–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2000.tb01066.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Gilboy N, Tanabe T, Travers D, Rosenau AM. Rockville (MD): Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (US); 2011. Emergency Severity Index (ESI): a triage tool for emergency department care, Version 4. Implementation handbook, 2012 ed. AHRQ Publication No. 12-0014. [Google Scholar]

- 29.SAS Institute, Inc. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2008. SAS®: Version 9.2 for Windows. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Calderon Y, Leider J, Hailpern S, Chin R, Ghosh R, Fettig J, et al. High-volume rapid HIV testing in an urban emergency department. AIDS Patient Care STDS. 2009;23:749–55. doi: 10.1089/apc.2008.0270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brown J, Shesser R, Simon G, Bahn M, Czarnogorski M, Kuo I, et al. Routine HIV screening in the emergency department using the new US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines: results from a high-prevalence area. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2007;46:395–401. doi: 10.1097/qai.0b013e3181582d82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chen JC, Goetz MB, Feld JE, Taylor A, Anaya H, Burgess J, et al. A provider participatory implementation model for HIV testing in an ED. Am J Emerg Med. 2011;29:418–26. doi: 10.1016/j.ajem.2009.11.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Christopoulos KA, Schackman BR, Lee G, Green RA, Morrison EA. Results from a New York City emergency department rapid HIV testing program. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2010;53:420–2. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e3181b7220f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Freeman AE, Sattin RW, Miller KM, Dias JK, Wilde JA. Acceptance of rapid HIV screening in a southeastern emergency department. Acad Emerg Med. 2009;16:1156–64. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2009.00508.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lubelchek RJ, Kroc KA, Levine DL, Beavis KG, Roberts RR. Routine, rapid HIV testing of medicine service admissions in the emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S65–70. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lyss SB, Branson BM, Kroc KA, Couture EF, Newman DR, Weinstein RA. Detecting unsuspected HIV infection with a rapid whole-blood HIV test in an urban emergency department. J Acquir Immun Defic Syndr. 2007;44:435–42. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e31802f83d0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Sattin RW, Wilde JA, Freeman AE, Miller KM, Dias JK. Rapid HIV testing in a southeastern emergency department serving a semiurban-semirural adolescent and adult population. Ann Emerg Med. 2011;58(1 Suppl 1):S60–4. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2011.03.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Silva A, Glick NR, Lyss SB, Hutchinson AB, Gift TL, Pealer LN, et al. Implementing an HIV and sexually transmitted disease screening program in an emergency department. Ann Emerg Med. 2007;49:564–72. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2006.09.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lyons MS, Lindsell CJ, Ledyard HK, Frame PT, Trott AT. Emergency department HIV testing and counseling: an ongoing experience in a low-prevalence area. Ann Emerg Med. 2005;46:22–8. doi: 10.1016/j.annemergmed.2004.12.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Merchant RC, Seage GR, Mayer KH, Clark MA, DeGruttola VG, Becker BM. Emergency department patient acceptance of opt-in, universal, rapid HIV screening. Public Health Rep. 2008;123(Suppl 3):27–40. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brown J, Kuo I, Bellows J, Barry R, Bui P, Wohlgemuth J, et al. Patient perceptions and acceptance of routine emergency department HIV testing. Public Health Rep. 2008;123:21–6. doi: 10.1177/00333549081230S304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Pisculli ML, Reichmann WM, Losina E, Donnell-Fink LA, Arbelaez C, Katz JN, et al. Factors associated with refusal of rapid HIV testing in an emergency department. AIDS Behav. 2011;15:734–42. doi: 10.1007/s10461-010-9837-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Christopoulos KA, Weiser SD, Koester KA, Myers JJ, White DA, Kaplan B, et al. Understanding patient acceptance and refusal of HIV testing in the emergency department. BMC Public Health. 2012;12:3. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-12-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]