Abstract

Injection drug users are at a high risk for a number of preventable diseases and complications of drug use. This article describes the implementation of a nurse-led health promotion and disease prevention program in New Jersey's syringe access programs. Initially designed to target women as part of a strategy to decrease missed opportunities for perinatal HIV prevention, the program expanded by integrating existing programs and funding streams available through the state health department. The program now offers health and prevention services to both men and women, with 3,488 client visits in 2011. These services extend the reach of state health department programs, such as adult vaccination and hepatitis and tuberculosis screening, which clients would have had to seek out at multiple venues. The integration of prevention, treatment, and health promotion services in syringe access programs reaches a vulnerable and underserved population who otherwise may receive only urgent and episodic care.

Syringe access programs (SAPs) provide a unique opportunity to increase access to integrated health promotion and disease prevention services among the hard-to-reach population of active injection drug users (IDUs). SAP clients are at a high risk for a number of preventable infectious diseases, including human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), hepatitis B virus (HBV), hepatitis C virus (HCV), sexually transmitted infections (STIs), and infectious complications of drug use, which can range from minor skin infections to life-threatening bacteremia. Women who are actively using substances or who are partners of active substance users represent a particularly hard-to-reach population at high risk for unintended pregnancy and HIV infection. Nationally, a majority of SAPs report providing some health-related services, such as HIV testing and hepatitis screening.1 However, a full range of health interventions that include health promotion, education, HIV prevention, and targeted health services is infrequently integrated into SAP programs in the United States.

Injection drug use has been a major risk factor for HIV transmission in New Jersey since early in the HIV epidemic, accounting for 37% of cumulative HIV cases.2 Internationally, there is clear evidence that SAPs, including needle-exchange programs, have reduced HIV transmission rates among IDUs in areas where they have been established. One of the most definitive studies of SAPs, conducted in 1997, focused on 81 cities worldwide. It found that HIV infection rates increased by 5.9% per year in 52 cities without SAPs and decreased by 5.8% per year in 29 cities with SAPs.3 Another study of HIV among IDUs in New York City from 1990 to 2001 found that HIV prevalence fell from 54% to 13% following the introduction of SAPs.4 Access to clean needles and syringes is an important public health strategy not only to decrease HIV but also to decrease HBV and HCV transmission among IDUs. A study in Baltimore, Maryland, demonstrated decreases in HIV and HCV infection incidence over time among IDUs recruited during four time periods from 1988 to 2008 but noted a lesser impact on HCV infection.5 The reported high of 5.5 cases of HIV per 100 person-years and 22 cases of HCV per 100 person-years in the 1988–1989 cohort decreased to 0.0 HIV infections per 100 person-years and 7.2 cases of HCV infection per 100 person-years in the 2005–2008 cohort.

New Jersey's SAPs were authorized by the New Jersey State Legislature through a 2006 statute,6 which decriminalized possession of a hypodermic syringe or needle by a consumer if the individual was carrying an identification card from the SAP. The first of five SAPs was established in Atlantic City, New Jersey, in late 2007. Programs in three other New Jersey cities—Camden, Paterson, and Newark—were opened in 2008, with a fifth opening in Jersey City in 2009. Each SAP is a program within an existing community-based organization that provides other services, such as outreach to the homeless and HIV counseling and testing (HCT).

This article describes the development and implementation of a nurse-led health promotion and disease prevention program in five New Jersey cities that demonstrates how a wide range of services can be provided at SAPs by integrating existing programs and funding streams available through the state health department. The Access to Reproductive Care and HIV Services (ARCH) program began in December 2009 when the New Jersey Department of Health (NJDOH) Division of HIV, STD, and TB Services approached New Jersey SAPs and offered funding to hire a nurse at each site to provide health promotion services. The program was initially designed to address missed opportunities to reduce perinatal HIV transmission by targeting women of childbearing age. By offering perinatal HIV prevention services, the program was designed to reach high-risk women before they were either HIV-positive or pregnant, to identify HIV-positive women and pregnant women in this high-risk setting, and to link them into appropriate care. Over time, the program has built on this mission to address a broad range of health issues for both women and men by integrating services supported through a number of NJDOH divisions, including hepatitis screening, adult immunizations, gonorrhea/chlamydia testing and treatment, and tuberculosis (TB) testing.

The ARCH program is a model example of a program collaboration and service integration (PCSI) initiative in that it maximizes the health benefits received by clients of SAPs by providing a range of prevention and treatment services in a single setting. Not only do these services benefit the recipients directly, but, on a public health level, the program provides a strategy to reduce infectious diseases, complications of drug use, unintended pregnancy, and perinatal HIV transmission by reaching a population at high risk for these problems.

METHODS

Development and implementation

All five SAP agencies agreed to be part of the ARCH program. SAPs are administered by community-based agencies that provide a varying range of hours and services (e.g., drop-in centers, case management, outreach, and HIV testing). One SAP is held in a mobile outreach van. By March 2010, a registered nurse was hired for each of the programs to provide health -services during the operating hours of each SAP. While the SAP services are provided anonymously, the ARCH nurses maintain confidential health records to document services they provide and to ensure continuity of care.

NJDOH contracted with an established resource center for HIV provider education based in a university school of nursing to provide ongoing training and technical assistance for the ARCH nurses. Nurse educators from the resource center organized an orientation program for the nurses and scheduled bimonthly meetings for education and collaborative learning. The resource center also helped the nurses identify local resources, establish standing orders for nursing interventions, and develop a standard client health record. Standing orders are reviewed, approved, and signed by the physicians affiliated with each agency. A nurse educator and NJDOH nurse visit each site twice each year for on-site mentoring and review of policies and procedures.

The nurses began offering a range of health promotion services at the sites, starting with basic nursing interventions, such as wound assessment and care; counseling on safer injection techniques and overdose prevention; and safer sex and reproductive counseling, including preconception and birth-control education. The nurses provided point-of-care pregnancy testing and linkages for pregnant women to prenatal care (PNC), reproductive health services, and substance use treatment. Women seeking pregnancy testing and referrals to PNC included female SAP clients, sexual partners of SAP clients, and women accessing other services in the agency.

As these initial services were accepted by clients, the steering committee, comprising the nurses and health department and resource center staff, began to explore other opportunities for services that could be integrated into ARCH through existing health department funding streams. NJDOH facilitated linkages to other health department services and projects so that, within a few months, the ARCH nurses were able to initiate HBV and HCV testing (with funding from the hepatitis screening program) and screening and treatment for gonorrhea and chlamydia (funded by the STI program). Laboratory testing was provided by the health department laboratory, and specimens were transported by state couriers. For each new service, standing orders based on national recommendations were developed by the resource center and standardized across sites. By the end of the second year, some ARCH sites were also providing TB screening and referral in conjunction with the state TB-control program.

Clients and services

To monitor and evaluate program implementation, a standardized template was developed for weekly reporting of aggregate numbers of ARCH client visits and services. These reports also included narratives about notable activities, and nurses were asked specifically to report on encounters with pregnant women. In March 2011, the template was modified to collect information about the number and demographic characteristics of new clients. In this article, we present data from January through December 2011 to characterize ARCH program clients and describe the integration of health services.

OUTCOMES

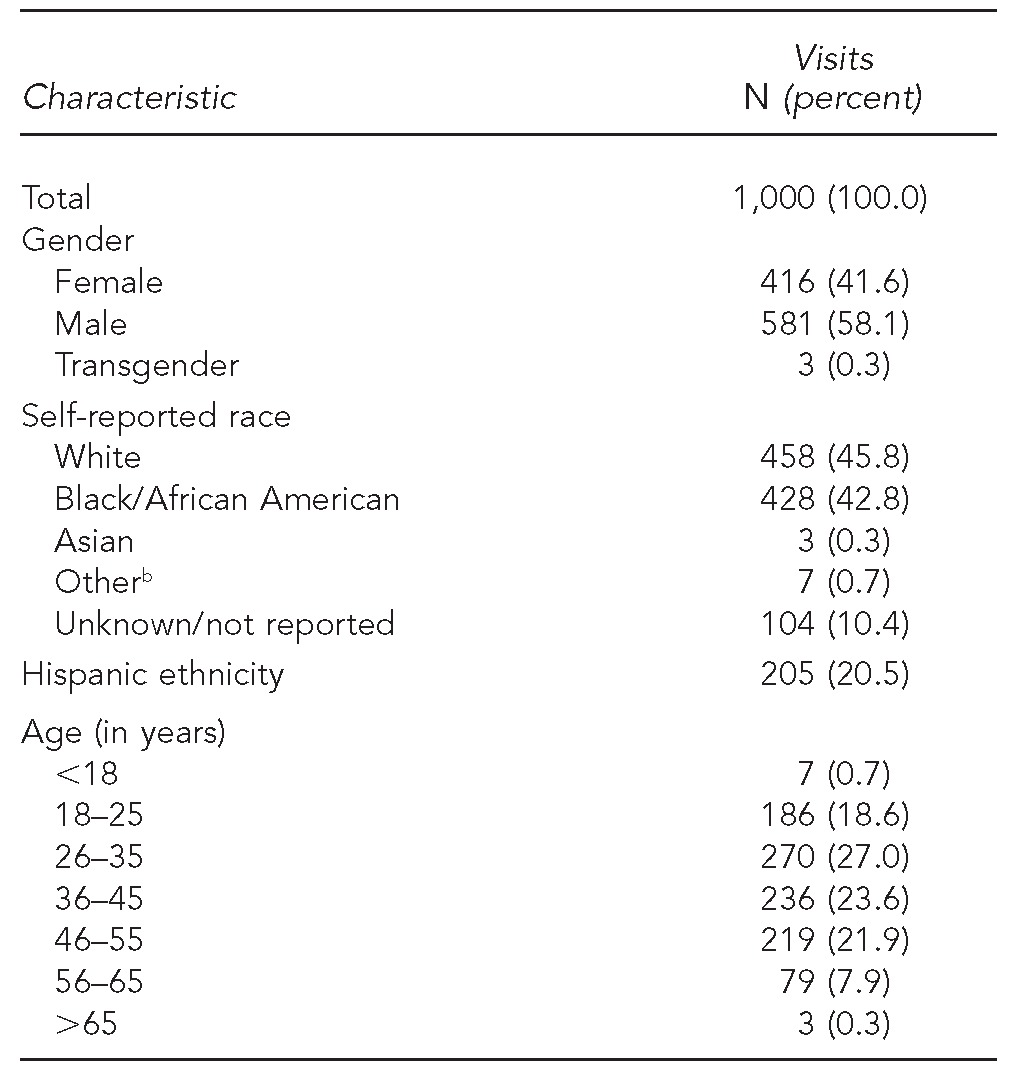

Nurses in the five ARCH sites had a total of 3,488 client visits in 2011; 38% of those visits were with women. The percentage of client visits with women ranged from a low of 27% to a high of 45% across the sites. From March through December 2011, 1,000 new clients entered the ARCH program. As shown in Table 1, 41.6% of new clients were female. Nearly half (45.8%) of the new clients were white, 42.8% were black/African American, and 20.5% identified as Hispanic.

Table 1.

Characteristics of new clients at five syringe access programs: ARCH program, New Jersey,a March 7–December 25, 2011

The syringe access programs were in five New Jersey cities: Atlantic City, Camden, Paterson, Newark, and Jersey City.

bIncludes Native American, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or Pacific Islander

ARCH = Access to Reproductive Care and HIV Services

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

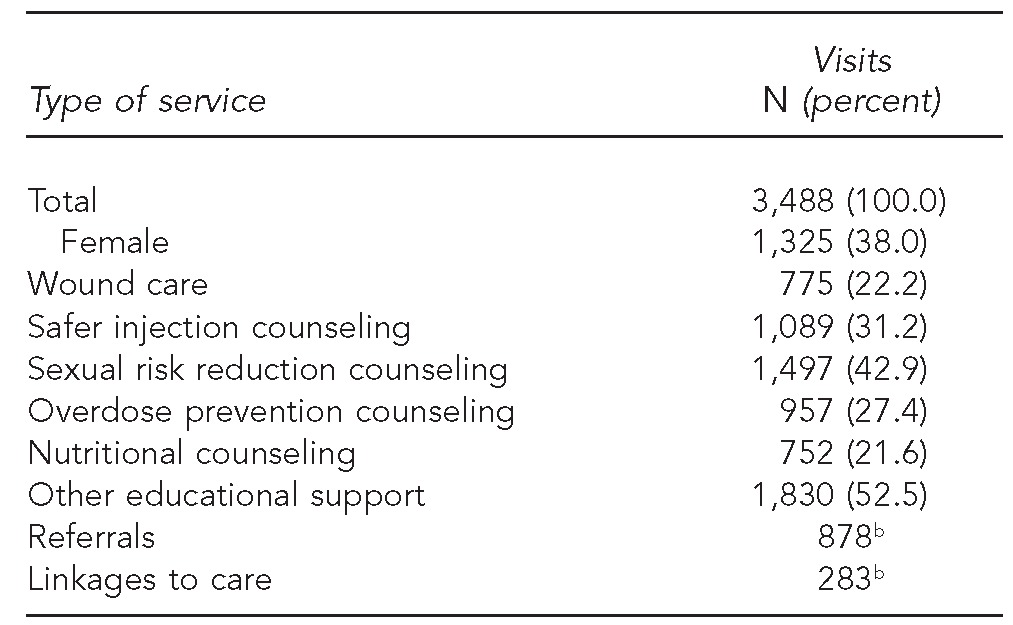

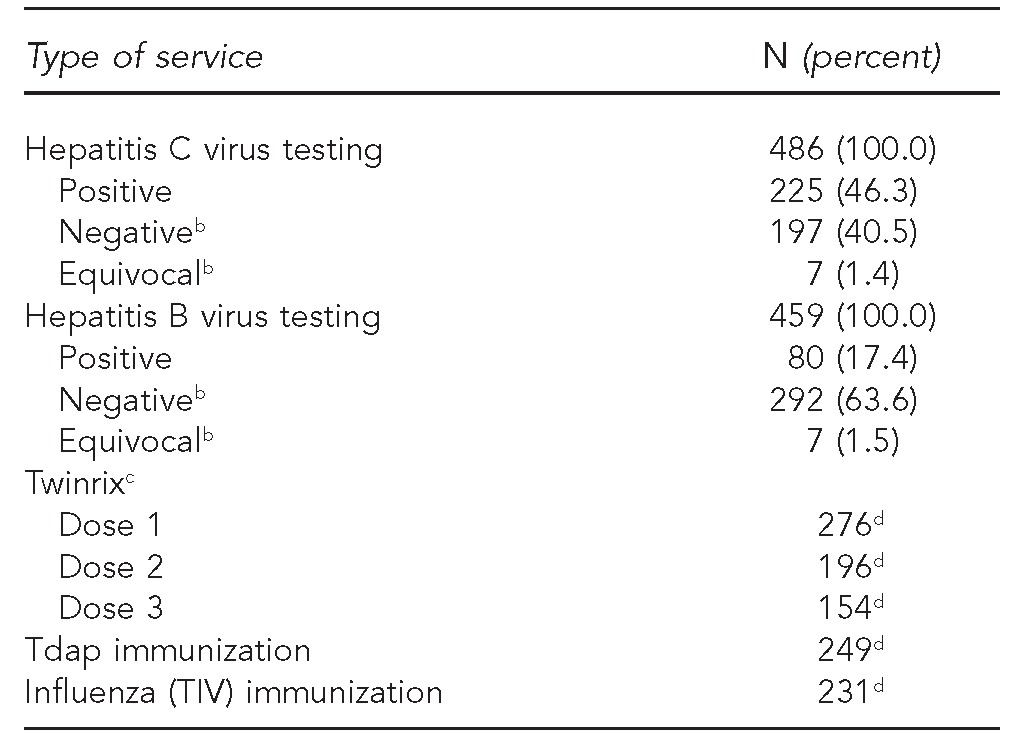

ARCH nurses provided a range of counseling and health promotion services. As shown in Table 2, wound care was provided during 22.2% of visits, overdose prevention counseling was provided at 27.4% of visits, and counseling on safer injection techniques was provided during 31.2% of visits. These services were targeted specifically toward IDUs, and the nurses reported that those services often laid the foundation for the provision of a range of other services. Screening for HBV and HCV and immunization against hepatitis A virus and HBV were seen by clients as particularly valuable and were often the initial reason for visits to the nurse. A total of 486 screening tests for HCV and 459 screening tests for HBV were conducted in 2011; 46.3% of clients tested positive for HCV, and 17.4% of clients tested positive for HBV (Table 3).

Table 2.

Nursing services provided at five syringe access programs: ARCH program, New Jersey,a January through December 2011

The syringe access programs were in five New Jersey cities: Atlantic City, Camden, Paterson, Newark, and Jersey City.

bPercentages are not provided for referrals and linkages to care because more than one referral or linkage could have been made at any visit.

ARCH = Access to Reproductive Care and HIV Services

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Table 3.

Hepatitis testing and adult immunizations at five syringe access programs: ARCH program, New Jersey,a January through December 2011

The syringe access programs were in five New Jersey cities: Atlantic City, Camden, Paterson, Newark, and Jersey City.

bAdded to reporting template in March 2011

cTwinrix is an immunization against hepatitis A virus and hepatitis B virus.

dPercentages not given for immunizations because each immunization is a freestanding event.

ARCH = Access to Reproductive Care and HIV Services

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Tdap = tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis

TIV = trivalent inactivated influenza vaccine

ARCH nurses provided educational support on a wide range of other health issues, as well as linkages and referrals to service. The nurses' notations in the weekly reports documented education about the management of chronic illness such as hypertension and heart disease, referrals after reported sexual assault, and support for continuing mental health treatment.

ARCH nurses did not directly offer HCT because HIV counselors were funded in the agencies to offer those services and the necessary follow-up. However, nurses provided counseling on HIV sexual risk reduction at 42.9% of visits, making that intervention the most frequently provided service (Table 2). The nurses administered more than 200 pregnancy tests, of which 47 were positive. Fifty-five clients were referred to PNC, including some who knew they were pregnant and came to see the ARCH nurse for help in accessing PNC (data not shown). The nurses noted in their reports that some of the clients whose pregnancy tests were positive decided to terminate the pregnancy and were given appropriate referrals.

A review of the weekly reports revealed 40 notations of visits with pregnant clients. Nurses routinely referred pregnant clients who were in an SAP or were using illicit drugs to methadone maintenance or in-patient drug treatment programs that included PNC. The nurses also saw a number of clients who were not IDUs but visited the ARCH nurse specifically to have a pregnancy test. The ARCH nurses linked the pregnant clients to PNC services. On at least four occasions, mothers who had been referred to drug treatment and PNC returned to see the ARCH nurse to thank her and the SAP staff for their help during the pregnancy and to introduce their healthy infants (data not shown).

Data from the aggregate weekly reports allow evaluation of program implementation in terms of numbers of clients and services, but additional work is needed to assess the program's effectiveness and its public health impact. A Web-based system for program reporting of anonymous individual-level data is currently being implemented and will provide a mechanism for enhanced evaluation of specific issues, including receipt of services over time.

LESSONS LEARNED

The ARCH program demonstrates that nurse-led health promotion services provided through SAPs can effectively reach large numbers of IDUs, including pregnant women. For clients from marginalized populations with limited access to health care (e.g., substance users), integration of services can mean that clients receive services that would otherwise be difficult to access. Little is reported in the literature on the inclusion of reproductive health or preconception care in the health services offered by SAPs. However, SAPs offer an opportunity to implement strategies to prevent perinatal HIV transmission by reaching out to women who are IDUs and might not otherwise access preconception or PNC services.

The Pediatric Spectrum of Disease project analyzed data from 4,755 HIV-exposed singleton deliveries during 1996–2000.7 The study found that maternal illicit drug use was a significant factor associated with lack of PNC. While maternal drug use did not have an independent effect on perinatal HIV transmission, lack of testing prior to delivery and lack of prenatal antiretroviral therapies were significantly associated with transmission. More recently, a review of 15 U.S. jurisdictions for birth years 2005–2008 found that HIV-positive mothers who reported substance use (i.e., drugs, alcohol, or tobacco) were twice as likely to have an HIV-infected child as those who did not report substance use.8 Reproductive health services offered through SAP initiatives such as ARCH provide a strategy to address missed opportunities for perinatal HIV prevention by offering education on safer sex and contraception; early identification of pregnancy; and linkages to PNC services, HIV testing, and treatment.

The literature documents the unmet health-care needs of IDUs and SAP clients.9 Heinzerling and colleagues interviewed 560 clients of 23 SAPs in California and asked about their receipt of 10 recommended preventive services.10 Clients reported receiving only 13% of recommended services, and 76% of those services were received at SAP visits. Nearly half of clients received none of the recommended services. A multivariate analysis found that more frequent SAP visits and use of drug treatment were associated with clients receiving recommended services.

Studies have examined various approaches to delivering health care to IDUs. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) reported on 184 SAPs operating in 2009 and found that the majority offered some preventive health and clinical services.1 Eighty-nine percent provided referrals to drug treatment, 87% offered HCT, 65% offered HCV counseling and testing, 55% offered STI screening, and 31% offered TB screening. A study from Australia reported on an SAP offering nurse-led primary health-care services. Clinic services had been used by 417 clients since the SAP opened in 2006. A review of the 200 most recent charts found that 64.5% of visits were to screen for bloodborne viruses and STIs. Ninety percent of clients returned for a follow-up visit. The authors concluded that health-care services run by nurses and co-located with SAPs fill an important gap in delivering health care.11

Health services are an integral component of care provided at the Insite Supervised Injecting Facility (SIF) in Vancouver, Canada, which offers injection stalls where IDUs can inject pre-obtained illicit drugs under the supervision of nurses.12 Nurses educate IDUs about safer injection practices, offer care for injection site infections, and refer clients for detoxification services and a range of other community and medical services. Compared with other health-care settings, clients reported that the SIF was a welcoming and nonjudgmental environment where they accessed a variety of services and received more timely access to primary health care and referrals as well as counseling and social services.13 Like the ARCH program, the Insite model addresses important barriers by providing multiple services at one convenient location, as well as addressing social factors that hinder clients' access to health services.

The findings of a CDC survey of HIV-associated behaviors and HIV prevalence among IDUs in 20 metropolitan statistical areas in 2009 underscore the need for increased HIV prevention and testing efforts. Sixty-nine percent of the 9,565 respondents who were HIV-negative or had unknown status reported having unprotected vaginal sex, 34% reported syringe sharing, but only 49% had ever been tested for HIV.14 A review of service models in New York State that integrate HCV prevention and care into SAPs, drug treatment, and HIV services found that a comprehensive, public health approach using a range of strategies enhanced access to HCV prevention and care for IDUs.15 Another approach to integrating services in New York City offered hepatitis screening and vaccines at publicly funded STI clinics.16 Sixty percent of IDUs attending the clinics reported that the availability of hepatitis services was the primary reason for their clinic visit. Of these clients, 54% had an STI exam and 59% had HCT. The authors concluded that integrated hepatitis services attracted IDUs to the STI clinic, where they benefited from services they might otherwise not have received. This finding is consistent with requests for hepatitis screening and vaccinations being the reason for many clients' initial contacts with ARCH nurses.

Available data clearly illustrate that SAPs have the potential to act as a gateway through which users learn about safe injection practices, safer sex education, and access to other prevention services, such as immunizations and referrals to HIV, hepatitis, and STI treatment. From an international perspective, the World Health Organization has stated that syringe access programs need to be supported by a range of complimentary services because syringe access alone will not control HIV infection among IDUs.17

CONCLUSIONS

The integrated services the ARCH program provided to SAP clients were initially targeted toward women as part of a strategy to decrease missed opportunities for perinatal HIV prevention. As the program was implemented and services evolved, it became clear that the ARCH program also offered an opportunity to provide an expanded range of integrated services in addition to reproductive health care to both men and women, including the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of HIV, hepatitis, and STIs; health education about safer injection and wound management; and linkages of clients into services such as PNC, hepatitis management, and TB treatment.

The ARCH program found that clients seek out and are receptive to services that will benefit them immediately, such as wound assessments and hepatitis immunizations. These services lay the groundwork for a relationship between the nurse and client and provide a gateway to other services, such as HIV risk reduction and reproductive health counseling, that can improve clients' health in the long term. ARCH services also extended the reach of state health department programs, such as adult vaccination and hepatitis and TB screening, which SAP clients would have had to seek out at multiple venues. By integrating prevention, treatment, and health promotion services provided by ARCH nurses, SAPS can reach a vulnerable and underserved population that otherwise may receive only urgent and episodic care.

The ARCH program represents an innovative model for PCSI. Services are delivered in a community setting that is accessible to a high-risk, vulnerable population of IDUs. A broad range of services is provided by establishing linkages with health department-funded programs that target this population. This initial evaluation of the ARCH project demonstrates that program integration for IDUs is feasible, acceptable to the clients, and has the potential to benefit the larger community by enhancing access to disease prevention and health promotion services among this underserved population. However, additional work is needed to evaluate program benefits and client outcomes.

Footnotes

The authors thank the current and past Access to Reproductive Care and HIV Services nurses for their contributions. A retrospective program evaluation was approved by the Institutional Review Board at the University of Medicine & Dentistry of New Jersey.

This project was supported in part through a memorandum of agreement between the François-Xavier Bagnoud Center, Rutgers School of Nursing, and the New Jersey Department of Health (NJDOH), Division of HIV, STD, and TB Services. The findings and conclusions in this article represent the views of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of NJDOH.

REFERENCES

- 1.Syringe exchange programs—United States, 2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2010;59(45):1488–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services, Public Health Services Branch, Division of HIV, STD, and TB Services. New Jersey HIV/AIDS report. Trenton (NJ): New Jersey Department of Health and Senior Services; 2011. Also available from: URL: http://www.state.nj.us/health/aids/documents/qtr0611.pdf [cited 2013 Feb 7] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hurley SF, Jolley DJ, Kaldor JM. Effectiveness of needle-exchange programmes for prevention of HIV infection. Lancet. 1997;349:1797–800. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(96)11380-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Des Jarlais DC, Perlis T, Arasteh K, Torian LV, Hagan H, Beatrice S, et al. Reductions in hepatitis C virus and HIV infections among injecting drug users in New York City, 1990–2001. AIDS. 2005;19(Suppl 3):S20–5. doi: 10.1097/01.aids.0000192066.86410.8c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mehta SH, Astemborski J, Kirk GD, Strathdee SA, Nelson KE, Vlahov D, et al. Changes in blood-borne infection risk among injection drug users. J Infect Dis. 2011;203:587–94. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiq112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. State of New Jersey Pub. L. 2006, c. 99, Bloodborne Disease Harm Reduction Act.

- 7.Peters V, Liu KL, Dominguez K, Frederick T, Mellville S, Hsu HW, et al. Missed opportunities for perinatal HIV prevention among HIV-exposed infants born 1996–2000, Pediatric Spectrum of HIV Disease Cohort. Pediatrics. 2003;111(5 Pt 2):1186–91. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Whitmore SK, Taylor AW, Espinoza L, Shouse RL, Lampe MA, Nesheim S. Correlates of mother-to-child transmission of HIV in the United States and Puerto Rico. Pediatrics. 2012;129:e74–81. doi: 10.1542/peds.2010-3691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Islam MM, Topp L, Day CA, Dawson A, Conigrave KM. The accessibility, acceptability, health impact and cost implications of primary healthcare outlets that target injecting drug users: a narrative synthesis of literature. Int J Drug Policy. 2012;23:94–102. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2011.08.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Heinzerling KG, Kral AH, Flynn NM, Anderson RL, Scott A, Gilbert ML, et al. Unmet need for recommended preventive health services among clients of California syringe exchange programs: implications for quality improvement. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2006;81:167–78. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2005.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Day CA, Islam MM, White A, Reid SE, Hayes S, Haber PS. Development of a nurse-led primary healthcare service for injecting drug users in inner-city Sydney. Aust J Prim Health. 2011;17:10–5. doi: 10.1071/PY10064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wood E, Tyndall MW, Montaner JS, Kerr T. Summary of findings from the evaluation of a pilot medically supervised safer injecting facility. CMAJ. 2006;175:1399–404. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.060863. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Small W, Van Borek N, Fairbairn N, Wood E, Kerr T. Access to health and social services for IDU: the impact of a medically supervised infection facility. Drug Alcohol Rev. 2009;28:341–6. doi: 10.1111/j.1465-3362.2009.00025.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.HIV infection and HIV-associated behaviors among injecting drug users—20 cities, United States, 2009. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2012;61(08):133–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Birkhead GS, Klein SJ, Candelas AR, O'Connell DA, Rothman JR, Feldman IS, et al. Integrating multiple programme and policy approaches to hepatitis C prevention and care for injection drug users: a comprehensive approach. Int J Drug Policy. 2007;18:417–25. doi: 10.1016/j.drugpo.2007.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hennessy RR, Weisfuse IB, Schlanger K. Does integrating viral hepatitis services into a public STD clinic attract injection drug users for care? Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):31–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.World Health Organization. Geneva: WHO; 2004. Policy Brief: Effectiveness of sterile needle and syringe programming in reducing HIV/AIDS among injecting drug users. Also available from: URL: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2004/9241591641.pdf [cited 2013 Feb 7] [Google Scholar]