Abstract

Objectives

We identified the level and type of program collaboration and service integration (PCSI) among HIV prevention programs in 59 CDC-funded health department jurisdictions.

Methods

Annual progress reports (APRs) completed by all 59 health departments funded by CDC for HIV prevention activities were reviewed for collaborative and integrated activities reported by HIV programs for calendar year 2009. We identified associations between PCSI activities and funding, AIDS diagnosis rate, and organizational integration.

Results

HIV programs collaborated with other health department programs through data-related activities, provider training, and providing funding for sexually transmitted disease (STD) activities in 24 (41%), 31 (53%), and 16 (27%) jurisdictions, respectively. Of the 59 jurisdictions, 57 (97%) reported integrated HIV and STD testing at the same venue, 39 (66%) reported integrated HIV and tuberculosis testing, and 26 (44%) reported integrated HIV and viral hepatitis testing. Forty-five (76%) jurisdictions reported providing integrated education/outreach activities for HIV and at least one other disease. Twenty-six (44%) jurisdictions reported integrated partner services among HIV and STD programs. Overall, the level of PCSI activities was not associated with HIV funding, AIDS diagnoses, or organizational integration.

Conclusions

HIV programs in health departments collaborate primarily with STD programs. Key PCSI activities include integrated testing, integrated education/outreach, and training. Future assessments are needed to evaluate PCSI activities and to identify the level of collaboration and integration among prevention programs.

In the past 30 years, health departments have played a central role in the nation's response to the domestic human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) epidemic. The federal government provides leadership in the form of guidance, technical support, and funding; however, the health department workforce at the state and local level implements these guidelines and HIV interventions. To address public health needs, health departments must adapt programmatic activities and services to changes in the local epidemic, scientific advances, and their fiscal situations. Recent discussions about optimizing health departments' efforts to address HIV prevention have included developing program collaboration and service integration (PCSI) approaches.1,2

In 2002, suggested integration strategies were identified in a joint statement by the National Association of State and Territorial AIDS Directors and the National Coalition of STD Directors.3 The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention's (CDC's) National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention (NCHHSTP) developed a conceptual framework for PCSI in 2007.1 NCHHSTP subsequently released a white paper in 2009 that refined these concepts and outlined NCHHSTP's vision for PCSI efforts. In this white paper, PCSI is defined as “a mechanism for organizing and blending interrelated health issues, activities, and prevention strategies to facilitate a comprehensive delivery of services.” Potential benefits of PCSI include maximizing opportunities for people to receive the best care and treatment when they interact with providers, eliminating duplicative services, and lowering costs.2

The momentum for more collaboration and service integration is grounded in a number of factors, including enhancing the capacity to address multiple health-related goals, decreasing barriers to providing services, maximizing federal and state resources, and responding to syndemics with similar risks for acquisition.2 The release of new CDC funding announcements supporting integrated approaches to service delivery, as well as the National HIV/AIDS Strategy4 in 2010, provides a great opportunity to enhance HIV prevention initiatives by collaborating and integrating with other programs.

HIV prevention services have been consistently included in recommendations related to PCSI activities; however, the scale to which PCSI efforts occur among HIV programs at health departments across the United States is unknown. The purpose of this study was to identify collaborative and integrative activities among CDC HIV prevention health department grantees and other health department programs, including viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), and tuberculosis (TB). In addition, we sought to determine if HIV funding, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) diagnosis rate, and organizational integration are factors that affect the level of PCSI activities. We used one year, 2009, to gain a general understanding of the type and scope of PCSI activities occurring in health departments. The data reviewed and analyzed in this study will (1) provide a picture of health department PCSI activities in 2009 and (2) serve as a baseline for future assessments of integration and collaboration among health departments.

METHODS

In 2009, CDC's Division of HIV/AIDS Prevention (DHAP) supported HIV prevention efforts funded under Program Announcement (PA) #04012 in all 50 states, Washington, D.C., six cities, the Virgin Islands, and Puerto Rico through cooperative agreements; each of these jurisdictions submitted an annual progress report (APR) to CDC regarding these activities. This analysis focused on three components of the 2009 APRs for PA #04012:5 (1) a series of open-ended questions regarding meaningful collaboration and service integration occurring among HIV, STD, viral hepatitis, and TB prevention efforts (Figure 1); (2) questions about HIV testing by type of location (e.g., STD clinic); and (3) representation on HIV community planning groups (a collaboration between health departments and communities to address the population needs of those infected with or at risk for HIV6) by other programs.

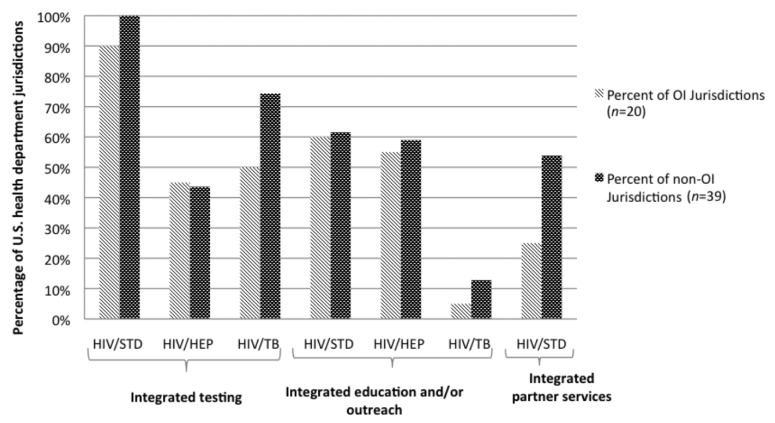

Figure 1.

Open-ended questions on meaningfula coordination and collaboration efforts in U.S. health departments (n=59) funded by CDC: PA #04012 annual progress reports, 2009

aFor example, joint testing, joint training of staff, joint training of providers, joint monitoring of data for trends, and integrated educational messages to common populations

bJurisdictions were asked to describe meaningful coordination and collaboration conducted in 2009 for each of these programs and facilities.

CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

PA = program announcement

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

STD = sexually transmitted disease

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

APRs were uploaded into NVivo® 8, a qualitative data management and analysis software.7 The responses to questions in Figure 1 were reviewed to create a codebook using a combination of emergent and a priori codes based on definitions and examples of PCSI strategies provided in the PCSI white paper.2 For this analysis, and to help categorize activities, program collaboration was defined as a mutually beneficial and well-defined relationship between two or more programs to achieve common goals, including joint funding of activities, sharing or joint analysis of surveillance and case-management data, creating joint data-collection systems, developing partnerships and coalitions with broad representation, and cross-training of providers and staff. Service integration was defined as the provision of seamless comprehensive services from multiple programs without repeated registration procedures, waiting periods, or other administrative barriers. Service integration includes the integration of HIV prevention, screening, testing, or treatment services with other health services in one clinical care setting.2

Three researchers reviewed the final qualitative codebook and applied codes to the text. After coding was complete, codes were combined into more general thematic categories. Frequencies were calculated for each category. Jurisdictions were then categorized by the funding level awarded by CDC in 20098 (low-level: $583,000–$2,060,000; mid-level: $2,060,001–$4,600,000; and high-level: $4,600,001–$27,200,000), rate of AIDS diagnosis per 100,000 population9 (low: 1.1–5.5; moderate: 5.6–10.3; and high: 10.4–27.0), and organizational integration (yes/no). Funding and AIDS diagnoses categories were calculated using 33rd and 66th percentiles. We defined organizational integration as health department programs that were integrated on an administrative level; program names in the APRs that included HIV and another disease or with a general name that included more than one disease were considered organizationally integrated. Funding level, AIDS diagnosis rate, and organization integration were selected for the analysis because information on each variable was readily available online or in the APR. We conducted Fisher's exact tests using SAS® version 9.310 to determine the association between PCSI activities and organizational integration, and Fisher-Freeman-Halton tests to determine the association between PCSI activities and funding and PCSI activities and AIDS diagnosis rate.

RESULTS

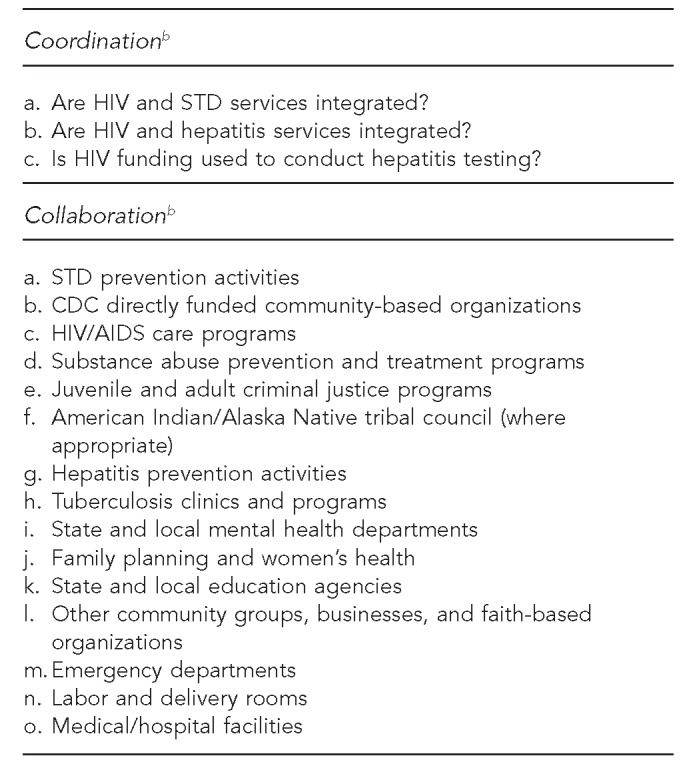

The main strategies identified for collaborative activities in health departments were non-HIV representation on HIV community planning groups, cross-training of staff and providers, collaborative funding, and staff sharing among programs. The primary service integration strategies were integrated testing, integrated education/outreach activities, and partner services (PS) activities (Table 1).

Table 1.

Main collaborative and integrative activities reported by HIV prevention programs in U.S. health departments (n=59) responding to annual progress reports: PA #04012, 2009

aNine jurisdictions either did not have representation from any of the programs listed or did not report enough detail to be included in the analysis on community planning groups.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

PA = program announcement

STD = sexually transmitted disease

TB = tuberculosis

DIS = disease intervention specialist

Program collaboration

Community planning groups and data.

In 50 (85%) jurisdictions, HIV community planning groups had representation from other programs: substance abuse (71%), STD (63%), mental health (54%), viral hepatitis (44%), and/or TB (17%). Twenty-four (41%) jurisdictions reported collaborative activities related to data, specifically data sharing, joint surveillance activities, and cross-matching cases. Twelve jurisdictions (20%) reported HIV programs sharing disease-related data with or receiving data from STD, TB, and/or viral hepatitis units of the health department. Joint surveillance activities were shared by the HIV program and at least one other program in three (5%) jurisdictions. Cross-matching cases of HIV with STD, TB, and/or viral hepatitis cases was found in seven (12%) jurisdictions (Table 1).

Training.

HIV prevention training for non-HIV prevention or care providers was reported in 49 (83%) jurisdictions. Providers working in the following areas received HIV prevention or testing training: prenatal or family planning (66%), labor and delivery (32%), substance abuse (31%), emergency rooms (19%), correctional facilities (17%), hospitals (17%), STD (14%), TB (12%), and mental health (10%). Trainings that focused on HIV and one other disease for providers of any specialty were reported in 31 (53%) jurisdictions. Multi-topic trainings occurred in 31 (53%) jurisdictions. Jurisdictions most often reported combined HIV and STD (39%) and HIV and viral hepatitis (27%) trainings. HIV prevention providers were trained in other disease areas in 19 (32%) jurisdictions. Twelve (20%) jurisdictions reported training HIV providers on viral hepatitis, nine (15%) trained HIV providers on STDs, and one (2%) trained providers on TB (Table 1).

Funding and staff sharing.

HIV prevention programs reported funding STD and viral hepatitis testing and education/outreach activities and sharing staff members with other programs. Among the 59 jurisdictions, 16 (27%) HIV prevention programs provided funds for STD testing and/or STD education/outreach activities. Twenty-seven (46%) HIV prevention programs provided funding for viral hepatitis testing and education/outreach. Staff sharing was most commonly reported between HIV prevention and STD programs (44%). The majority of HIV/STD staff sharing (n=23, 39%) occurred with disease intervention specialists (DISs) (Table 1).

Service integration

Testing.

Overall, integrated testing, or offering HIV testing with one or more other tests for STD, viral hepatitis, or TB infections, was reported by 58 (98%) of the 59 jurisdictions. Fifty-seven (97%) jurisdictions reported integrated HIV and STD testing. Integrated testing for HIV and TB was reported in 39 (66%) jurisdictions, while HIV and viral hepatitis testing was reported in 26 (44%) jurisdictions. Only nine (15%) jurisdictions reported HIV testing with two or more other tests at the same venue. Most integrated HIV/STD testing (n=54, 92%) occurred in STD clinics.

Education/outreach and PS.

Integrated education/outreach activities were reported by 45 (76%) jurisdictions. Thirty-six (61%) reported integrated HIV and STD education/outreach activities, 34 (58%) had integrated HIV and viral hepatitis activities, and six (10%) had integrated HIV and TB activities. Integrated PS among HIV and STD programs was reported in 26 (44%) jurisdictions (Table 1).

HIV funding, AIDS diagnosis rate, and organizational integration

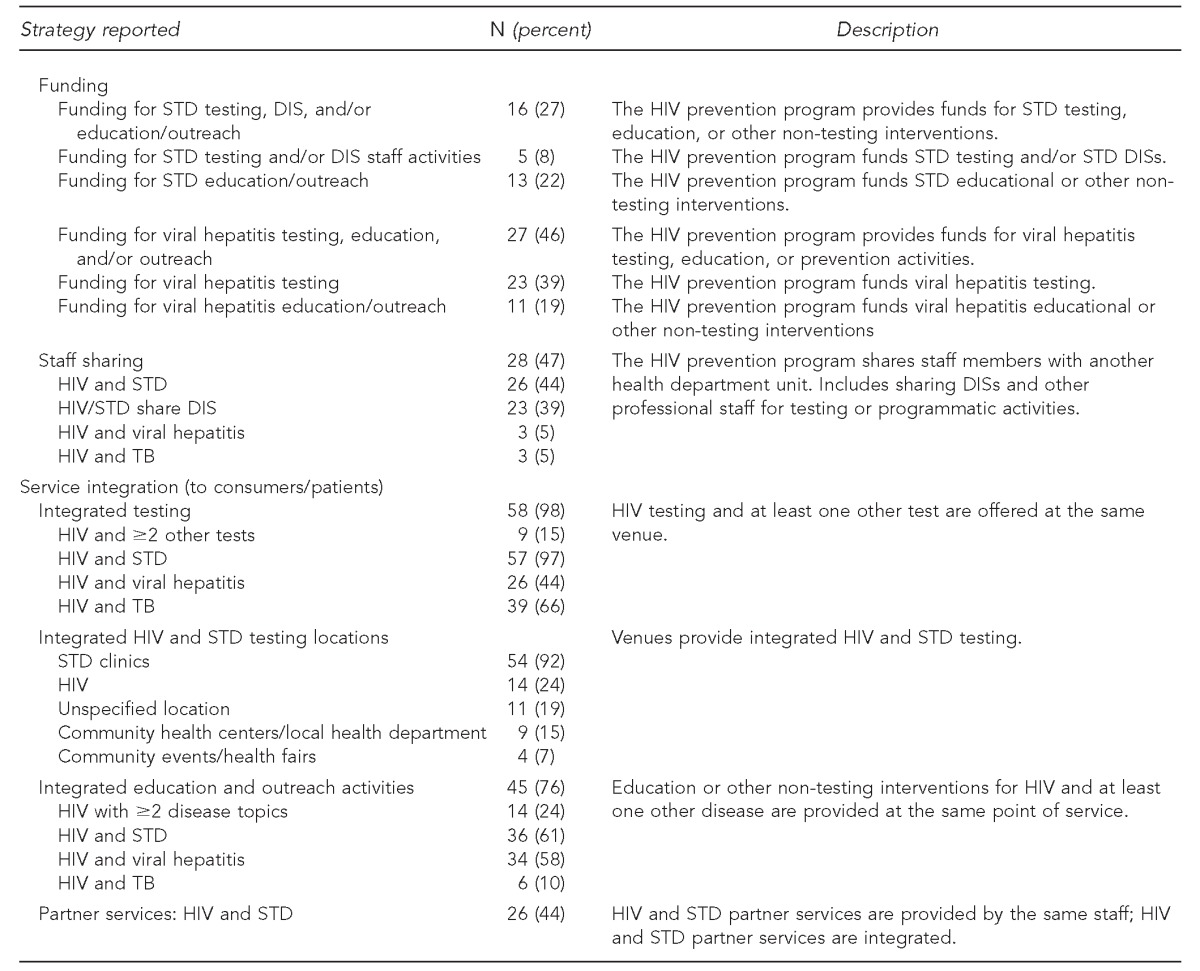

HIV funding and service integration.

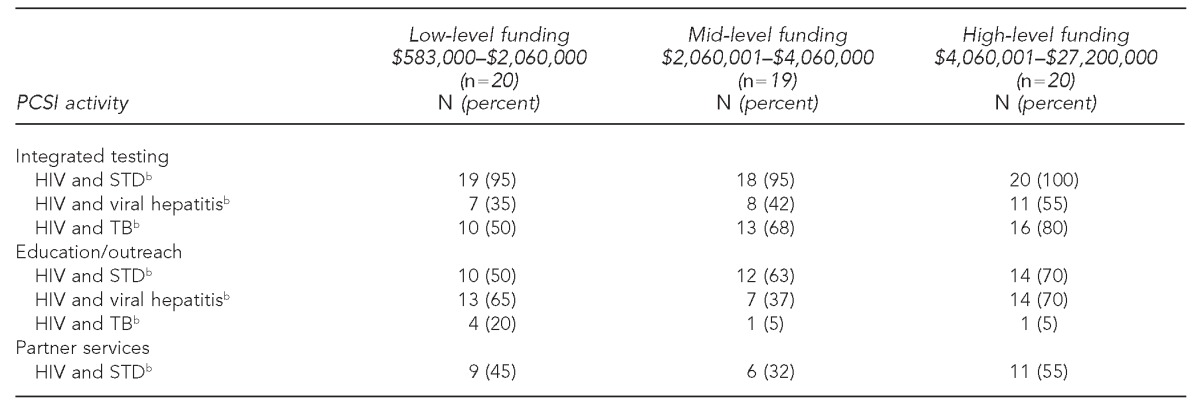

Twenty jurisdictions were categorized as low-level funded ($583,000–$2,060,000), 19 as mid-level funded ($2,060,001–$4,600,000), and 20 as high-level funded ($4,600,001–$27,200,000) (Table 2). Integrated HIV/STD testing was the most frequent type of integrated testing across all funding levels: 19 (95%) low-level funded, 18 (95%) mid-level funded, and 20 (100%) high-level funded jurisdictions. Eleven (55%) high-level funding jurisdictions reported integrated HIV/viral hepatitis testing. Integrated HIV/TB testing was reported in 10 (50%), 13 (68%), and 16 (80%) of low-, mid-, and high-level funding jurisdictions, respectively. No significant association was found between funding level and integrated testing activities.

Table 2.

Integrated HIV/STD, viral hepatitis, and TB testing, education/outreach, and partner services at U.S. health departments (n=59) in 2009, by PA #04012 funding levela

Funding levels were developed for this analysis using 33rd and 66th percentiles and do not reflect categories developed by the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

bAll analyses in the table were not significant (p>0.05) using the Fisher-Freeman-Halton test.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

STD = sexually transmitted disease

TB = tuberculosis

PA = program announcement

PCSI = program collaboration and service integration

Integrated education/outreach activities for HIV and STD were reported in 10 (50%) low-level funded jurisdictions, 12 (63%) mid-level funded jurisdictions, and 14 (70%) high-level funded jurisdictions. Education and outreach activities for HIV and viral hepatitis were found in 13 (65%), seven (37%), and 14 (70%) jurisdictions with low-, mid-, and high-level funding, respectively. HIV and TB education/outreach activities were found in four (20%) low-level funded jurisdictions, one (5%) mid-level funded jurisdiction, and one (5%) high-level funded jurisdiction. No significant association was found between funding level and integrated education/outreach activities.

Integrated HIV and STD PS were reported in nine (45%) low-level funded jurisdictions, six (32%) mid-level funded jurisdictions, and 11 (55%) high-level funded jurisdictions. No significant association was found between funding level and integrated PS (Table 2).

AIDS diagnosis rate and service integration.

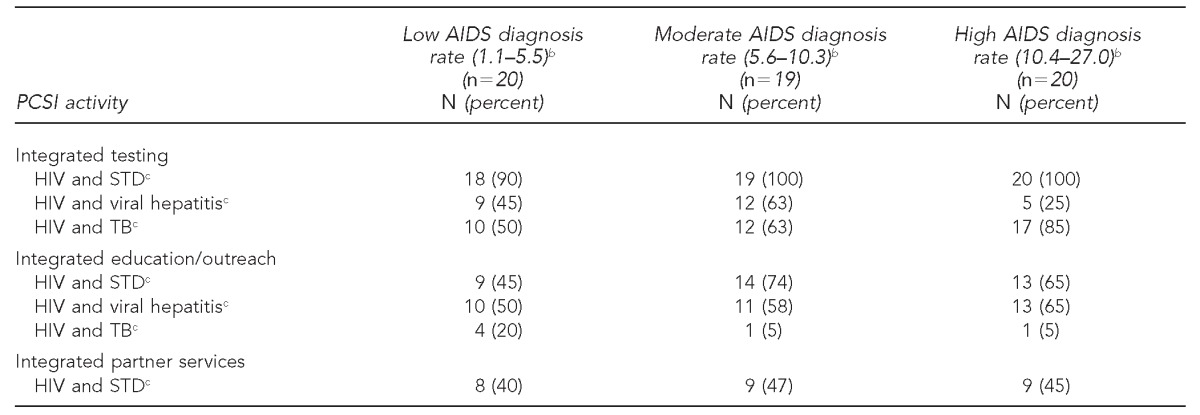

Of the 59 jurisdictions, 20 were categorized as having a low rate of AIDS diagnoses (1.1–5.5 per 100,000 population), 19 as having a moderate rate of AIDS diagnoses (5.6–10.3 per 100,000 population), and 20 as having a high rate of AIDS diagnoses (10.4–27.0 per 100,000 population). All jurisdictions with moderate and high rates of AIDS diagnoses, and almost all with low rates of AIDS diagnoses, had integrated HIV and STD testing programs (Table 3). Integrated testing activities for HIV and viral hepatitis were found in nearly two-thirds (63%) of jurisdictions with moderate AIDS diagnosis rates. Integrated HIV and TB testing activities were found in 10 (50%), 12 (63%), and 17 (85%) jurisdictions with low, moderate, and high rates of AIDS diagnoses, respectively. No significant associations were found between AIDS diagnosis rate and integrated testing activities.

Table 3.

Number of U.S. health departments (n=59) reporting integrated HIV, STD, viral hepatitis, and TB testing, education/outreach, and partner services in 2009, by AIDS diagnosis ratea

Categories for AIDS diagnoses were developed for this analysis using the 33rd and 66th percentiles and do not reflect how the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention defines a state's level of AIDS diagnosis rates. The 2009 AIDS diagnosis rates were taken from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/pdf/table20.pdf and http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report/pdf/table24.pdf

bPer 100,000 population

cAll analyses in the table were not significant (p>0.05) using the Fisher-Freeman-Halton test.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

STD = sexually transmitted disease

TB = tuberculosis

AIDS = acquired immunodeficiency syndrome

PCSI = program collaboration and service integration

Integrated education/outreach activities for HIV and STD programs were found in nine (45%) jurisdictions with low AIDS diagnosis rates, 14 (74%) jurisdictions with moderate AIDS diagnosis rates, and 13 (65%) jurisdictions with high AIDS diagnosis rates. Integrated HIV and viral hepatitis education/outreach programs were found in 10 (50%) jurisdictions with low AIDS diagnosis rates, 11 (58%) jurisdictions with moderate rates of AIDS diagnoses, and 13 (65%) jurisdictions with high AIDS diagnosis rates. Few jurisdictions across all categories of AIDS diagnosis rates reported having integrated HIV and TB education/outreach activities. No significant associations were found between education and outreach activities and AIDS diagnosis rates.

PS for HIV and STD programs were found in eight (40%), nine (47%), and nine (45%) jurisdictions with a low, moderate, and high AIDS diagnosis rate, respectively. No significant associations were found between AIDS diagnosis rate and HIV/STD PS integration (Table 3).

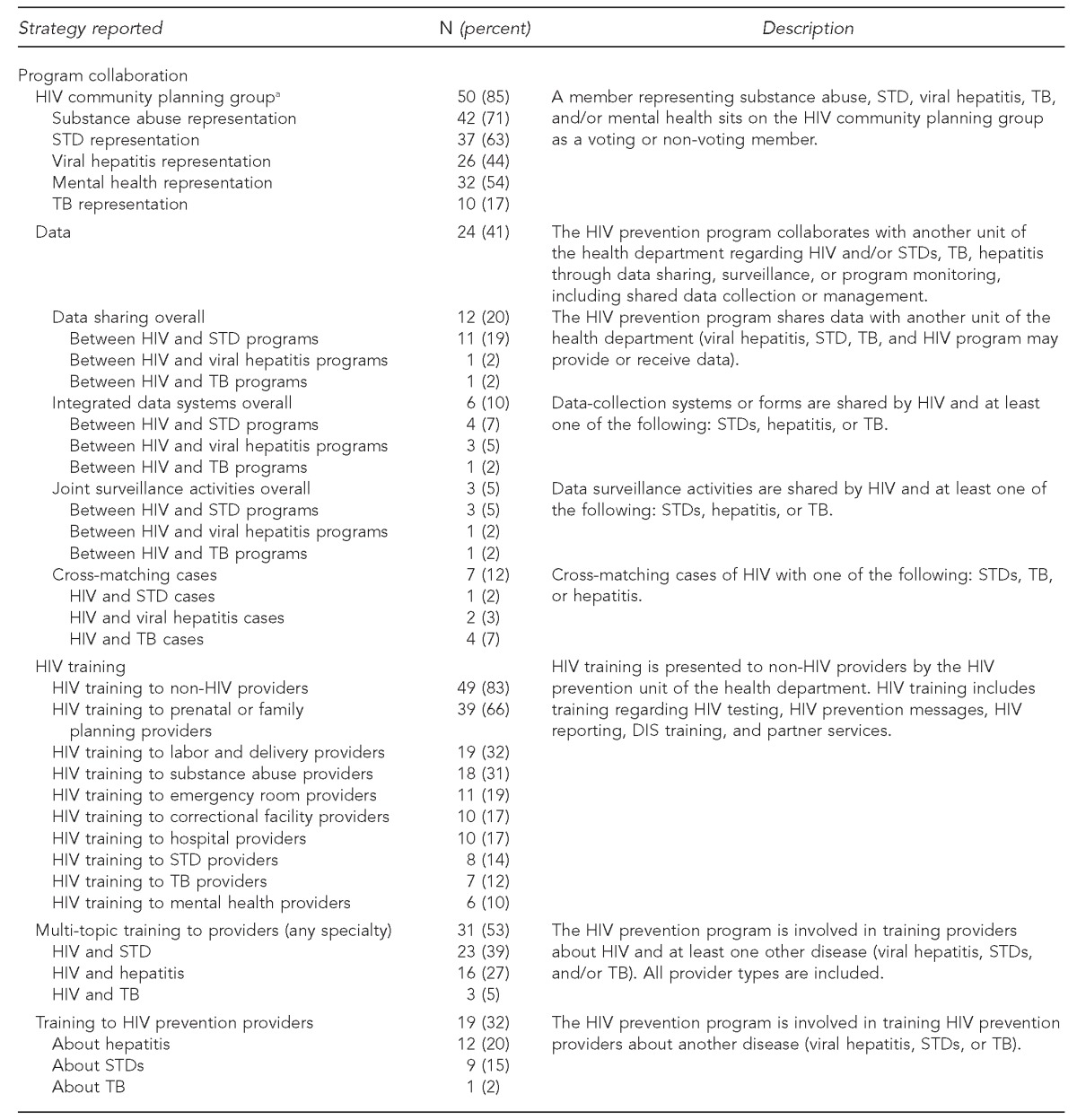

Organizational integration.

Twenty (34%) of the 59 HIV prevention programs were organizationally integrated (OI) with another infection program (Figure 2). Among jurisdictions that were OI, 18 (90%) reported integrated HIV/STD testing. All (100%) non-OI jurisdictions reported integrated HIV/STD testing. Nine (45%) OI jurisdictions and 17 (44%) non-OI jurisdictions reported integrated HIV/viral hepatitis testing. HIV/TB integrated testing activities were found in 10 (50%) OI jurisdictions and 29 (74%) non-OI jurisdictions (p>0.05).

Figure 2.

Percent of U.S. health department jurisdictions (n=59) reporting integrated testing, education/outreach, and partner services activities, by organizational integration,a 2009b

aOrganizational integration occurs when health department programs are administratively integrated. For this study, program names in the annual progress reports were used to determine the presence of organizational integration: program names that included HIV and another disease (e.g., HIV/STD program) or programs with an inclusive general name (e.g., communicable disease prevention program) were considered OI.

bA greater proportion of non-OI jurisdictions than OI jurisdictions reported integrated testing, education/outreach, and partner services for HIV and all diseases with the exception of HIV and hepatitis testing. None of these results was statistically significant.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

STD = sexually transmitted disease

HEP = hepatitis

TB = tuberculosis

OI = organizationally integrated

Integrated HIV and STD education/outreach programs were found in 12 (60%) OI jurisdictions and 24 (62%) non-OI jurisdictions. HIV and hepatitis education or outreach activities were found in 11 (55%) OI jurisdictions and 23 (59%) non-OI jurisdictions. Integrated education or outreach programs for HIV and TB were found in one (5%) OI jurisdiction and five (13%) non-OI jurisdictions. Twenty-one (54%) non-OI and five (25%) OI jurisdictions reported integrated HIV/STD PS.

Although a greater proportion of non-OI jurisdictions reported integrated activities than OI jurisdictions in nearly every category, none of these results were statistically significant (Figure 2).

DISCUSSION

This review of health departments' progress reports found that all jurisdictions conducted some level of PCSI activities. Integrated testing, education and outreach activities, and PS were the main service integration activities found in the review. HIV prevention programs were involved in collaborative activities with other health department programs around provider training, community planning groups, and data sharing, in addition to allocating staff and HIV funds for non-HIV-specific activities. HIV and STD programs were the most frequent partnerships found in both service integration and program collaboration, while HIV programs worked with TB programs least often. This finding has been found in at least one other external survey.11 The levels of HIV funding, AIDS diagnosis rate, and OI among health department programs were not found to be individually significant factors in the level of PCSI activities reported; however, it is likely that a combination of factors including others not examined, such as size of health departments and staff interest, contribute to integration and collaboration.

The opportunities around integrating surveillance data to help direct interventions and resources are highlighted in other publications,12–14 as is the success of locally driven initiatives to integrate, match, and share data.12,15,16 However, the findings in this study of APRs showed that only 20% (n=12) of health departments shared data with another health department program. A 2009 survey of 47 federally funded STD programs found that 28% reported having “limited integration,” defined as maintaining separate surveillance systems but comparing select data to guide interventions.12 Matching data sources for coinfection was reported for 26% of these STD programs, while cross-matching cases in our study was reported for 12% of the jurisdictions. The low number of health departments sharing information and data may indicate a need for -enhancing communication and cross-sharing of data, when appropriate. The impact of PCSI efforts for public health action is likely limited if data are not shared between programs.

Barriers to developing and sustaining PCSI activities will need to be addressed. Structural challenges such as incompatible data systems13 and policies and laws that restrict combining funding streams and sharing data can inhibit efforts to form a PCSI approach to address disease burden in a jurisdiction.4,17 All levels of government will need to address these and other challenges and to support local and state PCSI initiatives to provide comprehensive services to communities.

Some action has been taken to mitigate obstacles. In November 2008, CDC released updated guidelines for delivering integrated PS.18 CDC also established data security standards for all programs in 201119 to address inconsistent data security and confidentiality procedures across different disease programs that impede data sharing and other collaborative work with data. Additionally, a summary guidance for integrated services for people who use illicit drugs was published in 2012.20 Because of the time frame in which these guidelines were released, jurisdictions may have initiated more integrated activities around PS, data collaboration, and illicit drug use after completion of the 2009 APRs. Future surveys are needed to assess the implementation of these guidelines.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. First, the table included in the APR asked about coordination and collaboration; it was not intended to be a survey of PCSI efforts. Second, some questions were more specific than others, such as asking directly about HIV funding used for hepatitis testing, which may yield a more accurate response from health departments. Third, the analysis represents cross-sectional data. We did not have the ability in this analysis to link dependent and independent variables. Fourth, information on target populations and those receiving services were not consistently available in the APRs for analysis. Additionally, because the APRs were completed from the HIV program's perspective at the state level, this review most likely does not capture all PCSI-related activities occurring within health departments and at the local level. Lastly, jurisdictions sometimes used the terms collaboration, integration, and coordination interchangeably. Although this limitation was addressed in the analysis by using formal definitions previously defined in the PCSI white paper2 to assign activities as either collaboration or integration, it suggests that any future assessments or surveys of PCSI activities should clearly define which activities are considered collaboration or integration.

CONCLUSION

This article describes the primary ways HIV programs collaborated and integrated services with other disease programs and in other settings in 2009. This review will allow future assessments of PCSI to identify trends and driving factors for collaboration and integration. Additionally, it will inform the development of improved tools to evaluate PCSI activities. State health departments differ structurally and fiscally and have distinct epidemics to address; thus, the type and level of PCSI activities will vary across jurisdictions. Because of these differences, it is important for government agencies at all levels to work together to evaluate PCSI activities and identify the appropriate level and types of collaboration and integration to maximize resources, sustain programs, and meet the needs of communities.

Footnotes

It was determined by the National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention, in lieu of Institutional Review Board review, that this study was a public health program activity and was not considered research. The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

REFERENCES

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2007. Program collaboration and service integration: enhancing the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, STD, and TB in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2009. Program collaboration and service integration: enhancing the prevention and control of HIV/AIDS, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis in the United States. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wohlfeiler D HIV/STD Workgroup. STD/HIV prevention integration. Washington: National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors and National Coalition of STD Directors; 2002. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Office of National AIDS Policy (US) National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States. Washington: ONAP; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2003. US program announcement #04012 (2004–2008), HIV prevention projects, notice of availability of funds. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) 2003–2008 HIV prevention community planning guidance. Atlanta: CDC; 2003. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/pubs/hiv-cp.pdf [cited 2012 Oct 23] [Google Scholar]

- 7.QSR International Pty Ltd. Burlington (MA): QSR International Pty Ltd.; 2008. NVivo®: Version 8. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) DHAP HIV funding awards by state and dependent area (fiscal year 2009) 2010. [cited 2012 May 7]. Available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/topics/funding/state-awards/2009/index.htm.

- 9.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2011. HIV surveillance report: diagnoses of HIV infection and AIDS in the United States and dependent areas, 2009. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/hiv/surveillance/resources/reports/2009report [cited 2013 Feb 1] [Google Scholar]

- 10.SAS Institute, Inc. SAS®: Version 9.3 for Windows. Cary (NC): SAS Institute, Inc.; 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Alliance of State and Territorial AIDS Directors and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. Washington and Menlo Park (CA): NASTAD and Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2009. The national HIV prevention inventory: the state of HIV prevention across the U.S. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dowell D, Gaffka NH, Weinstock H, Peterman TA. Integration of surveillance for STDs, HIV, hepatitis, and TB: a survey of U.S. STD control programs. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(Suppl 2):31–8. doi: 10.1177/00333549091240S206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Weinstock H, Douglas JM, Jr, Fenton KA. Toward integration of STD, HIV, TB, and viral hepatitis surveillance. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(Suppl 2):5–6. doi: 10.1177/00333549091240S202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ward JW, Fenton KA. CDC and progress toward integration of HIV, STD, and viral hepatitis prevention. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):99–101. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stenger MR, Courogen MT, Carr JB. Trends in Neisseria gonorrhoeae incidence among HIV-negative and HIV-positive men in Washington State, 1996–2007. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(Suppl 2):18–23. doi: 10.1177/00333549091240S204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gaffga NH, Samuel MC, Stenger MR, Stover JA, Newman LM. The OASIS project: novel approaches to using STD surveillance data. Public Health Rep. 2009;124(Suppl 2):1–4. doi: 10.1177/00333549091240S203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Whiticar P, Liberti T. Advancing integration of HIV, STD, and viral hepatitis services: state perspectives. Public Health Rep. 2007;122(Suppl 2):91–5. doi: 10.1177/00333549071220S218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Recommendations for partner services programs for HIV infection, syphilis, gonorrhea, and Chlamydial infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR09):1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) Atlanta: CDC; 2011. Data security and confidentiality guidelines for HIV, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted disease, and tuberculosis programs: standards to facilitate sharing and use of surveillance data for public health action. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/nchhstp/programintegration/docs/PCSIDataSecurityGuidelines.pdf [cited 2013 Jan 9] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Belani H, Chorba T, Fletcher F, Hennessey K, Kroeger K, Lansky A, et al. Integrated prevention services for HIV infection, viral hepatitis, sexually transmitted diseases, and tuberculosis for persons who use drugs illicitly: summary guidance from CDC and the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2012;61(RR-5):1–47. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]