Abstract

Public health professionals face many challenges in infectious disease cluster case identification and partner notification (PN), especially in populations using social media as a primary communication venue. We present a method using Facebook and social network diagram illustration to identify, link, and notify individuals in a cluster of syphilis cases in young black men who have sex with men (MSM). Use of Facebook was crucial in identifying two of 55 individuals with syphilis, and the cooperation of socially connected individuals with traditional PN methods yielded a high number of contacts per case. Integration of PN services for HIV and sexually transmitted diseases, as well as collaboration between the city and state information systems, assisted in the cluster investigation. Given that rates of syphilis and HIV infection are increasing significantly in young African American MSM, the use of social media can provide an additional avenue to facilitate case identification and notification.

Syphilis rates nationally are increasing among men who have sex with men (MSM), especially young black MSM aged 20–29 years. From 1999 to 2008, there was an eightfold increase in the rate of syphilis among black MSM over the absolute increase in the rate among white MSM.1 The Wisconsin Division of Public Health (WDPH) also reported an increase in syphilis diagnoses among young black MSM in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. From 2000 to 2008, there was a 144% increase in human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) diagnoses among black MSM aged 15–19 years in Milwaukee County.2 In the summer of 2011, staff at the City of Milwaukee Health Department (MHD) began linking cases of syphilis among young black MSM into the cluster described in this article and searching for better tools to improve the process of case identification and partner notification (PN). PN is the process of identifying the partners, suspects, and associates of people diagnosed with sexually transmitted diseases (STDs) to notify them of their exposure to disease and to convince them to seek evaluation and treatment.3

BACKGROUND

Sexually active people, especially MSM, are increasingly finding sexual partners via the Internet, through geosocial global positioning system networking applications (e.g., Grindr) that facilitate proximity-based sexual partnering,4,5 personal advertisements on sites such as craigslist.org and manhunt.net, and other Internet forums.6–8 Such online venues for meeting partners may be associated with more risky sexual behaviors, such as unprotected anal intercourse,9,10 and are associated with syphilis infection among MSM.11 At the same time, traditional PN methods, such as phone calls, field visits, and mailing letters, while productive in many situations, are not keeping up with these trends. For example, current methods of PN for MSM with syphilis in the United States reaches only about 14% of partners.12 Anonymous partners, insufficient locating information, and limited rapport between interviewer and interviewee can make disease investigation among MSM difficult. Public health practitioners have developed Web-based tools such as inSPOT13 to conduct PN, but these tools have yielded low contact rates.14,15 In outbreaks of syphilis and other STDs, PN strategies have included sending e-mail messages to partners, albeit with limited success.13

Public health professionals have used social media tools16 for interventions involving health communication, survey research, and information dissemination. Social media tools refer to communication methods involving the Internet and mobile technologies that involve social interaction and/or regularly updated information. Examples include downloadable products (e.g., buttons and badges), image and video sharing, syndication (e.g., rich-site summary feeds, podcasts, and widgets), eCards, mobile technologies, Twitter, blogs, and social network sites (e.g., Facebook). In STD prevention, public health practitioners have used the Internet to collect information from target groups such as MSM, provide information regarding STD prevention, engage risk groups in interventions, and link users to testing services.17 However, such innovative public health practices may encounter barriers from organizational human resource policies that limit the use of online social media sites18 and block websites with explicit sexual content.19

As of late 2012, Facebook had approximately 1 billion users, 584 million of whom were active daily users.20 In 2010, 75% of those aged 18–29 years had a social network profile, with Facebook overwhelmingly the most commonly used site.21 Little is known about the use of Facebook as a PN tool, as few published examples exist.17 However, Internet-based PN methods for MSM have been shown to be well accepted22 and effective.23 We describe the experience of the MHD in using Facebook as a complementary approach to traditional tools to investigate, notify, and elicit partners in a syphilis cluster primarily involving young African American MSM.

METHODS

General approach to PN

Disease intervention specialists (DISs) at MHD follow up on newly identified early syphilis cases in eight counties in southeastern Wisconsin, newly identified HIV cases in Milwaukee County, and reported gonorrhea and chlamydia cases in Milwaukee. DISs are public health workers who interview patients for their sex partners' identifying and locating information. They find and notify those partners and try to convince partners to seek evaluation and treatment.3 At the MHD, PN services for HIV and STDs are integrated. In syphilis PN, MHD staff and supervisors aim for the following local performance measures: a contact index (i.e., the number of sexual partners named with sufficient information to initiate an investigation per infected individual who was interviewed) of 2.0, a cluster index (i.e., the number of suspects and associates named with sufficient information to initiate an investigation per infected individual who was interviewed) of 0.5, and a treatment index (i.e., the number of partners, suspects, and associates treated per infected individual) of 1.25. Due to limited cooperation in naming sexual partners, achieving these goals has been difficult in past investigations.

Two DISs investigated almost all of the syphilis cases in this cluster identified by the MHD from July 2011 to June 2012, using traditional PN techniques along with Facebook as described hereafter. Both DISs were women older than 25 years of age of who have lived in Milwaukee more than 15 years. One DIS identified herself as African American and the other as biracial with African American heritage. They received formal training in PN methods from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and have 16 combined years of field experience. All PN services at MHD are supervised and coordinated by three CDC Public Health Advisors who are assigned to MHD, each with more than 20 years of field experience.

Cluster definitions

We included individuals in this cluster if they were linked to the index case as a sexual partner, suspect, or associate (Table 1) and if there was enough information (e.g., name, telephone number, address, or Facebook name) to initiate an investigation.24 We defined a sexual partner as a person named by the case as a sexual partner. A suspect was a person named by the infected individual as someone who had symptoms, was a partner of other people known to be infected, or might benefit from evaluation for syphilis (e.g., pregnant females and roommates). An associate was a person named by noninfected individuals as someone who had symptoms, was a partner of other people known to be infected, or might benefit from evaluation for syphilis (e.g., pregnant females and roommates). As the investigation is ongoing, for the purposes of this article, inclusion in this cluster was limited to individuals identified as partners, suspects, or associates as of June 22, 2012.

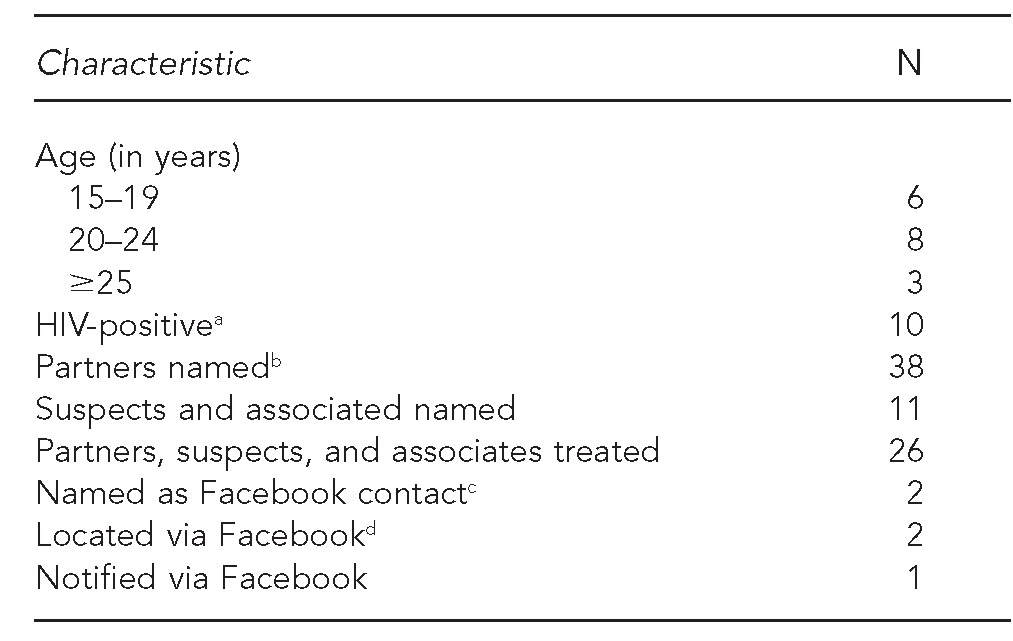

Table 1.

Characteristics of cases (n=17) in a syphilis cluster in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2011–2012

aOne individual refused HIV testing.

bNamed with enough information to initiate an investigation

cIdentified as case because named as Facebook contact of another individual in the cluster

dPhoto from Facebook used to identify one case at initial in-person contact.

HIV = human immunodeficiency virus

Using Facebook as an adjunct for PN

In the fall of 2011, DIS staff at the STD/HIV program at MHD began using Facebook in addition to traditional methods to locate and notify partners of patients infected with syphilis. During interviews early in the cluster investigation, DIS staff found that several of the young men used social networking sites, including Facebook, Gay Black Chat, and Men4RentNow, rather than e-mail for general communication and specifically for finding sexual partners. According to the administrative protocol at MHD, e-mail communication (via inSPOT) involves passing information to a client via a third party, a process that DIS staff noted in past investigations slowed PN and decreased confidentiality. Following standard practice to protect confidentiality, DIS staff at MHD did not use text messaging or e-mail for PN or for reporting test results while investigating this cluster of syphilis.

A DIS staff member set up an account and profile on Facebook. The account name used a male pseudonym based on very common names in America. The profile included a moniker and links that emphasized general health promotion, not specifically related to STDs or the MSM community. The account settings eliminated the account from Internet search engines.

With administrative oversight and approval, the DIS staff discussed and agreed on a brief, generic message template they used in Facebook messages to ask clients to “call about an important issue regarding [their] health.” Messages were sent privately in a manner that could not be mistakenly posted by the receiving individual to a public forum. Sending messages typically did not require establishing a social network connection (i.e., friending). In the few cases in which individuals had privacy settings to block messages, DIS staff requested “friend” status with individuals in the cluster to send the generic messages. If Facebook friending was required to send messages, DIS staff “de-friended” (i.e., severed the Facebook connection with) the individual after receiving a phone call from the individual or after the individual did not reply to multiple messages. To protect privacy, DIS staff never “friended” more than one individual at a time, thereby preventing social contacts (i.e., friends) of the account from viewing a list of other friends to the account. DIS staff turned down all unsolicited requests to establish social connections (i.e., friend requests) to the Facebook account.

City (MHD) and state (WDPH) public health staff met in spring 2012 to review cases in the cluster. MHD staff provided information on syphilis, gonorrhea, and chlamydia infections from one information system (STD*MIS). WDPH provided HIV statuses from another information system (LUTHER).

RESULTS

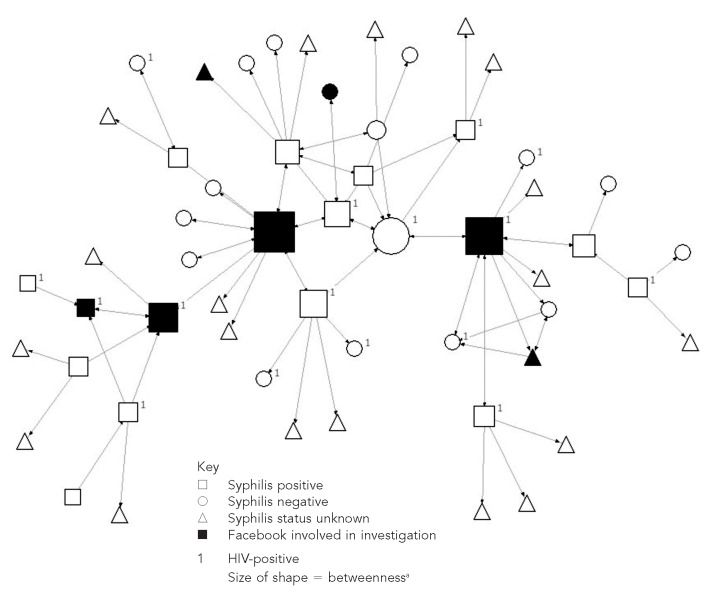

A total of 55 individuals met the cluster definition (Figure). Fifty-one of the 55 individuals had known ages: 20 were aged 15–19 years, 25 were aged 20–24 years, and six were aged ≥25 years (age range: 15–48 years; median: 20 years). Of the 55 individuals, 17 tested negative for syphilis, 21 were not tested (data not shown), and 17 test positive for syphilis (Table 1). Fifteen of the 17 infected individuals resided in Milwaukee, and the other two resided elsewhere in southeastern Wisconsin. All 55 individuals in the cluster were African American. Of the four women in the cluster, none was actually a partner of the men in the cluster, two tested negative, and two were not tested. Coinfections included two with chlamydia and 10 with HIV. Five men in the cluster had HIV only. Venues for meeting sexual partners did not include bars or bathhouses (data not shown).

Figure.

Social network diagram of syphilis cases and contacts in a 2011–2012 cluster in Milwaukee, Wisconsin

NOTE: Chart created with UCINET. Borgatti SP, Everett MG, Freeman LC. UCINET for Windows: software for social network analysis. Harvard (MA): Analytic Technologies; 2002.

aMimiaga MJ, Tetu AM, Gortmaker S, Kroenen KC, Fair AD, Novak DS, et al. HIV and STD status among MSM and attitudes about Internet partner notification for STD exposure. Sex Transm Dis 2008;35:111-6.

Within this cluster, DIS staff at MHD were able to complete epidemiologic follow-up on 37 partners, suspects, and associates. Among these 37 individuals, MHD staff were able to link 17 new cases of syphilis to this cluster; 20 other individuals tested negative (data not shown). Epidemiologic follow-up was not completed on the other 18 individuals because they could not be located, they refused clinical evaluation, they were out of jurisdiction, or there was unverifiable or false information provided by cases about partners, suspects, and associates.

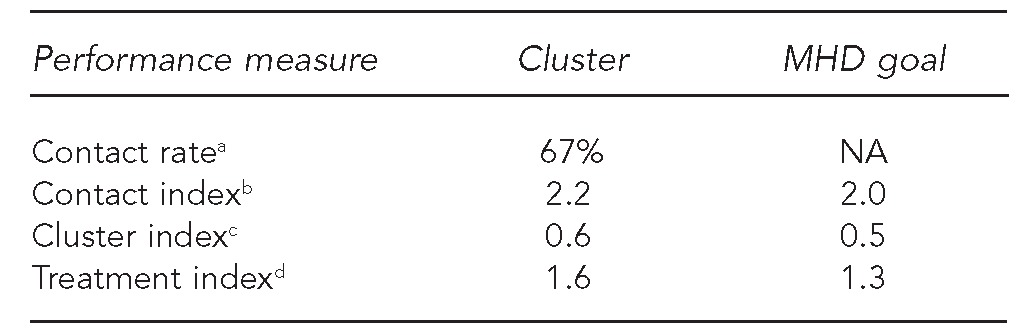

Performance measures of the PN efforts exceeded local goals (Table 2). Anecdotally, DIS staff noted that a few of the young MSM in this cluster were unusually cooperative in naming partners, especially compared with older cases and contacts in numerous previous investigations.

Table 2.

Performance measures for a syphilis cluster investigation in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, 2011–2012

NOTE: Performance measures are defined using: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US), Division of STD Prevention, National Center for HIV/AIDS, STD, and TB Prevention. 2007 performance measures companion guidance: comprehensive STD prevention systems, prevention of STD-related infertility, and syphilis elimination program announcement. Atlanta: CDC; November 2006. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/std/program/2007PMguidance1-3-07.pdf [cited 2013 Feb 8].

aThe contact rate was based on 17 infected individuals plus 20 who tested negative divided by 55.

bThe contact index was based on 38 partners named by infected individuals divided by 17 infected individuals.

cThe cluster index was based on 10 suspects and associates divided by 17 infected individuals.

dThe treatment index was based on 27 partners, suspects, and associates treated divided by 17 infected individuals.

MHD = Milwaukee Health Department

NA = not applicable

DIS staff identified two of the 17 infected individuals in the cluster solely on the basis of being named by a partner as a Facebook contact. In five other individuals in the cluster, DIS staff found that the use of Facebook augmented traditional partner investigation and notification methods by helping the staff to:

Reach partners more quickly than by phone, thereby shortening the time to testing and treatment;

Contact individuals who change addresses and phone numbers frequently, but who consistently access and maintain their Facebook accounts, sometimes via computers at libraries or at schools;

Identify individuals in person by viewing photos online; and

Identify friends and family who could help contact the individual in the cluster.

Facebook also allowed individuals to respond privately and at their convenience.

The following anecdote illustrates how Facebook augmented traditional methods. While attempting to contact an individual named as a partner of another individual in the cluster, the DIS sent several private Facebook messages from the Facebook account set up for this purpose. The individual did not respond to these messages. The DIS also viewed photos of the individual on his Facebook profile. Months later, the DIS recognized the individual in the hallway of the STD clinic and expedited his testing and presumptive treatment for syphilis.

DIS staff also noted the following limitations of Facebook in PN:

Some individuals do not access their account with any regularity.

Individuals may not respond at all, even though repeated messages are sent.

Because nicknames or tag names are often used, it can be difficult to confirm the identity of a partner.

Some individuals adjust the privacy settings on their Facebook accounts such that they will not appear in general searches.

Two new HIV infections were identified during this investigation, including one individual who seroconverted three months after counseling. One individual who was HIV-positive but syphilis negative was a key connector between otherwise unconnected parts of the cluster. His central location appears in the social network diagram (Figure) as a large empty circle between two large filled squares.25 By correlating data from STD and HIV information systems, MHD and WDPH staff linked previously unconnected HIV cases using information from the syphilis cluster, as was accomplished in a previous study.26

DISCUSSION

In this cluster of syphilis cases, a combination of traditional and Facebook-augmented methods of PN yielded large numbers of partners, suspects, and associates of index cases being investigated, as demonstrated by high performance measures relative to established local aims at MHD. We believe that this effective PN effort resulted from both the use of Facebook and greater-than-usual cooperation by individuals in the cluster. Factors that may have led to the increased cooperation included younger age, comfort with DIS staff, and several individuals who were particularly socially connected and cooperative in naming multiple partners.

An additional asset that facilitated understanding the importance of Facebook-augmented methods of PN was a visualization of the cluster. The network diagram (Figure) depicts the partnerships that constitute the cluster. A metric called “betweenness”25 emphasizes individuals who are key in holding together subsets of a cluster. In clusters of infectious disease, key connectors with positive disease status can introduce infections to otherwise unconnected subsets of people. In the current cluster, two of the most significant connectors had positive syphilis tests, as well as Facebook involved in their identification as members of the cluster. They appear in the network diagram as large filled squares. The network diagram offers additional key information. For example, between the two filled squares or connector individuals, appearing as a large empty circle with a “1,” is another key connector who tested negative for syphilis, did not have Facebook involved in his PN, but was known to be HIV-positive. This individual's positioning within the network as a key connector makes focused intervention efforts all the more vital. Although using Facebook was instrumental in investigating some key connectors in this syphilis cluster, further research is needed to specifically examine how to optimize the use of Facebook as a PN tool, and more broadly to address social media as a tool for epidemiologic investigation and follow-up.

Because syphilis and HIV coinfection is common,27 integration of STD and HIV PN services at the local level (MHD) facilitated rapid recognition of this cluster and allowed disparate parts of this cluster to be connected. However, separate STD and HIV information systems presented challenges that required significant efforts by city (MHD) and state (WDPH) public health staff to correlate information on the individuals in this cluster. Better communication through electronic bridges between databases would help with integrating HIV and syphilis services in future investigations.

Although DIS staff identified and located the majority of individuals in this syphilis cluster using traditional methods of PN, augmenting this approach with Facebook not only yielded improved PN outcomes, but also demonstrated that enhanced techniques serve to connect parts of the sexual networks that otherwise would not have been connected. Such enhanced techniques have previously shown similar improved outcomes in Chlamydia contact tracing28 and investigating hepatitis C connections in injection drug users.29 In addition, by using Facebook, DIS staff found two individuals, or 3.6% of 55 individuals in the cluster, who were not reachable using traditional methods. In five other instances, DIS staff used Facebook to augment traditional methods of PN. Research has shown that e-mail-based PN may not reach young people who use social media as a communication method. A recent study found that 29% of teens aged 12–17 years send daily messages via social networking sites such as Facebook, while only 6% of them send daily e-mails.30 Adults aged 18–29 years use social networking sites significantly more (92%) than any other age group.31 Because of increasing rates of syphilis and HIV in younger subpopulations that increasingly use social media to locate sexual partners, public health officials might consider whether to incorporate Facebook into PN for both infections.

Limitations

This study was subject to several limitations. For one, the results MHD staff achieved with PN in this cluster may not apply outside of a similar population of young, urban, Midwestern, African American MSM. Secondly, DIS staff members with different training, personal backgrounds, experience, supervision, and protocols may achieve different results. Furthermore, future research should address whether PN augmented by social media is cost-effective or consistently improves outcomes of contact investigations

CONCLUSIONS

Our experience, along with limited evidence from previous studies, suggests that traditional methods should not be discarded and that social media may complement the identification and notification of additional individuals. Systematic study in a variety of settings is needed to clarify the roles of traditional PN and social media tools in achieving outcomes of rapid disease identification and subsequent reduction in community transmission. We encourage public health practitioners to continue to share their professional experiences with social media tools through professional organizations and at related training sessions.32

In addition, our experiences suggest that health departments interested in proactively using new media to enhance contact investigations should carefully assess the effectiveness of such efforts in improving health outcomes.

As occurred in this cluster investigation, DIS staff accessing social media, especially sites with explicit sexual content, need to follow organizational confidentiality policies to maintain clients' trust and not reveal private information within online venues. Given the ongoing demographic trends of increasing use of Facebook and similar or future social media technologies, combining traditional PN methods and using social networking sites may be an effective strategy in improving the outcomes of integrated STD and HIV prevention efforts by public health agencies within the communities they serve.

Footnotes

The authors thank Sandra Mattson, BA, Darlene Turner-Harper, MPA, and Thomas Peterman, MD, of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), Office of Infectious Diseases, National Center for HIV/AIDS, Viral Hepatitis, STD, and TB Prevention; and James Vergeront, MD, Mari Gasiorowicz, MA, and Marissa Stanley, MPH, of the Wisconsin Division of Public Health (WDPH).

The findings and conclusions in this article are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of CDC or WDPH. Institutional review board approval was not sought because the analysis of the information related to the cluster was conducted as quality improvement of partner services provided at the City of Milwaukee Health Department.

REFERENCES

- 1.Su JR, Beltrami JF, Zaidi AA, Weinstock HS. Primary and secondary syphilis among black and Hispanic men who have sex with men: case report data from 27 states. Ann Intern Med. 2011;155:145–51. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-155-3-201108020-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Increase in newly diagnosed HIV infections among young black men who have sex with men—Milwaukee County, Wisconsin, 1999–2008. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2011;60(4):99–102. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Recommendations for partner services programs for HIV infection, syphilis, gonorrhea, and Chlamydial infection. MMWR Recomm Rep. 2008;57(RR-9):1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Landovitz RJ, Tseng CH, Weissman M, Haymer M, Mendenhall B, Rogers K, et al. Epidemiology, sexual risk behavior, and HIV prevention practices of men who have sex with men using GRINDR in Los Angeles, California. J Urban Health. 2012 Sep 15; doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9766-7. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rudy E, Beymer M, Aynalem G, Rodriguez J, Plan A, Bolan R, et al. Grindr and other geosocial networking applications: advent of a novel, high-risk sexual market place. Proceedings of the 2012 National STD Prevention Conference; 2012 May 12–15; Minneapolis. Also available from: URL: https://cdc.confex.com/cdc/std2012/webprogram/Paper29712.html [cited 2012 Jun 23] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Newman LM, Dowell D, Bernstein K, Donnelly J, Martins S, Stenger M, et al. A tale of two gonorrhea epidemics: results from the STD Surveillance Network. Public Health Rep. 2012;127:282–92. doi: 10.1177/003335491212700308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McFarlane M, Bull SS, Rietmeijer CA. The Internet as a newly emerging risk environment for sexually transmitted diseases. JAMA. 2000;284:443–6. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.443. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Benotsch EG, Kalichman S, Cage M. Men who have met sex partners via the Internet: prevalence, predictors, and implications for HIV prevention. Arch Sex Behav. 2002;31:177–83. doi: 10.1023/a:1014739203657. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liau A, Millett G, Marks G. Meta-analytic examination of online sex-seeking and sexual risk behavior among men who have sex with men. Sex Transm Dis. 2006;33:576–84. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000204710.35332.c5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.White JM, Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Mayer KH. HIV sexual risk behavior among black men who meet other men on the Internet for sex. J Urban Health. 2012 Jun 12; doi: 10.1007/s11524-012-9701-y. [epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.California Department of Public Health, Center for Infectious Diseases. California syphilis elimination surveillance data, 2010. Sacramento (CA): California Department of Public Health; 2010. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdph.ca.gov/data/statistics/Documents/STD-Data-Syphilis-Elimination-Surveillance-Data.pdf [cited 2012 Jun 23] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hogben M, Paffel J, Broussard D, Wolf W, Kenney K, Rubin S, et al. Syphilis partner notification with men who have sex with men: a review and commentary. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32(10 Suppl):S43–7. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000180565.54023.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Plant A, Rotblatt H, Montoya JA, Rudy ET, Kerndt PR. Evaluation of inSPOTLA.org: an internet partner notification service. Sex Transm Dis. 2012;39:341–5. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e31824e5150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Internet use and early syphilis infection among men who have sex with men—San Francisco, California, 1999–2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52(50):1229–32. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Using the Internet for partner notification of sexually transmitted diseases—Los Angeles County, California, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2004;53(6):129–31. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (US) The health communicator's social media toolkit. Atlanta: CDC; 2011. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/socialmedia/Tools/guidelines/pdf/SocialMediaToolkit_BM.pdf [cited 2012 Jun 23] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Jenkins WD, Wold B. Use of the Internet for the surveillance and prevention of sexually transmitted diseases. Microbes Infect. 2012;14:427–37. doi: 10.1016/j.micinf.2011.12.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sharing Mayo Clinic. Guidelines for Mayo Clinic employees and students who participate in social media [cited 2012 Nov 27] Available from: URL: http://sharing.mayoclinic.org/guidelines/for -mayo-clinic-employees.

- 19.OpenDNS®. OpenDNS 2010 report: Web content filtering and phishing. San Francisco: OpenDNS; 2011. Also available from: URL: http://www.opendns.com/pdf/opendns-report-2010.pdf [cited 2012 Nov 27] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Facebook. Newsroom: key facts [cited 2012 Nov 24] Available from: URL: http://newsroom.fb.com/content/default.aspx?News AreaId=22.

- 21.Taylor P, Keeter S, editors. Millennials: a portrait of generation next: confident. Connected. Open to change. Washington: Pew Research Center; 2010. Also available from: URL: http://www.pewsocialtrends.org/files/2010/10/millennials-confident-connected-open-to -change.pdf [cited 2012 Jun 23] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mimiaga MJ, Tetu AM, Gortmaker S, Kroenen KC, Fair AD, Novak DS, et al. HIV and STD status among MSM and attitudes about Internet partner notification for STD exposure. Sex Transm Dis. 2008;35:111–6. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3181573d84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Klausner JD, Wolf W, Fischer-Ponce L, Zolt I, Katz MH. Tracing a syphilis outbreak through cyberspace. JAMA. 2000;284:447–9. doi: 10.1001/jama.284.4.447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) Program operations: guidelines for STD prevention: partner services. Atlanta: CDC; 2011. Also available from: URL: http://www.cdc.gov/std/program/partners.pdf [cited 2012 Jun 23] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hanneman RA, Riddle M. Introduction to social network methods: chapter 10—centrality and power. Riverside (CA): University of California, Riverside; 2005. Also available from: URL: http://faculty.ucr.edu/~hanneman/nettext/C10_Centrality.html#Betweenness [cited 2012 Jun 23] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Potterat JJ, Phillips-Plummer L, Muth SQ, Rothenberg RB, Woodhouse DE, Maldonado-Long TS, et al. Risk network structure in the early epidemic phase of HIV transmission in Colorado Springs. Sex Transm Infect. 2002;78(Suppl 1):i159–63. doi: 10.1136/sti.78.suppl_1.i159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Karp G, Schlaeffer F, Jotkowitz A, Riesenberg K. Syphilis and HIV co-infection. Eur J Intern Med. 2009;20:9–13. doi: 10.1016/j.ejim.2008.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Brewer DD, Potterat JJ, Muth SQ, Malone PZ, Montoya P, Green DL, et al. Randomized trial of supplementary interviewing techniques to enhance recall of sexual partners in contact interviews. Sex Transm Dis. 2005;32:189–93. doi: 10.1097/01.olq.0000154492.98350.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Brewer DD, Hagan H, Hough ES. Improved injection network ascertainment with supplementary elicitation techniques. Int J STD AIDS. 2008;19:188–91. doi: 10.1258/ijsa.2007.007167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lenhart A. Teens, smartphones and texting. Washington: Pew Research Center; 2012. Also available from: URL: http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2012/Teens-and-smartphones/Summary -of-findings.aspx [cited 2012 Jun 23] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brenner J. Washington: Pew Research Center; 2012. Pew Internet: social networking (full detail) Also available from: URL: http://pewinternet.org/Commentary/2012/March/Pew-Internet-Social -Networking-full-detail.aspx [cited 2012 Jun 23] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), National Network of STD/HIV Prevention Training Centers. Core training programs: partner services and program support [cited 2012 Jun 23] Available from: URL: http://depts.washington.edu/nnptc/core_training/partner/index.html.