Abstract

Non puerperal uterine inversions resulting from mixed mullerian uterine sarcoma are rare. We present a case of a postmenopausal woman with a large mixed mullerian tumour presenting as a huge abdominopelvic mass. It required a challenging surgical procedure to remove the tumour which is also described along with the review of literature.

Background

Non-puerperal uterine inversions are uncommon, and most of the cases that have been reported are caused by benign tumours, including leiomyomas.1 Seldom does a malignant uterine tumour present as uterine inversion. The clinical diagnosis can be difficult due to the distorted anatomy. Owing to the rarity of this condition, most of the cases would be operated on without any surgical experience. We present a rare case with a large abdominal mass and uterine inversion caused by an uncommon tumour, that is, mixed mullerian tumour that was removed using a unique surgical technique.

Case presentation

A 60-year-old woman presented to our gynaecology outpatient clinic with postmenopausal bleeding associated with foul smelling discharge for 1 month. On examination, she was a healthy woman with a body mass index of 23. She was hypothyroid, on irregular treatment, anaemic (haemoglobin (Hb) 5 g/dL) and was found to be hypertensive with a blood pressure of 180/120. There was no obvious lymphadenopathy. An abdominal examination revealed a non-tender firm mass arising from the pelvis of about 16–18 weeks gravid uterus. A vaginal speculum examination showed a fleshy mass filling whole of vagina. Foul yellow pus mixed with blood was present. The vagina and vulva were ulcerated probably due to the intense infection. Only a gentle one finger examination per vaginum was possible due to the stenosed vagina and exquisite tenderness. The cervix was not palpable till high up. The uterus was felt about 16–18 weeks size in continuity with the vaginal mass.

Investigations

An ultrasound sonography (USG) for whole abdomen was performed, which revealed a uterine mass of heterogenous echogenicity. The fundus seemed intact. Bilateral ovaries were found normal. There was no free fluid. All other organs were normal. The MRI or CT scan was not performed due to the non-affordability by the patient.

Differential diagnosis

Our clinical differential diagnosis was a leiomyosarcoma with inversion (since cervix was not palpable) or cervical fibroid having undergone sarcomatous change.

Treatment

The patient was unfit for any surgery due to an uncontrolled blood pressure, poor respiratory reserve and uncontrolled hypothyroidism. She was started on antibiotics, antihypertensives and thyroxine. She also received three units of blood transfusion preoperatively to build up the Hb level. A severe hypertension and the associated changes in ECG and echocardiography made her a high anaesthetic risk candidate for surgery. Owing to the painful vaginal examination and high anaesthesia risk, she was posted straightforwardly to definitive surgery without a preliminary biopsy.

Intraoperatively, the patient was opened up abdominally. A complete uterine prolapse was seen with the tubes and ligaments prolapsing into the cervical ring. A posterior cervical incision was given as described in the Haultain procedure through which the fundus of the uterus was delivered only after the multiple pieces of the sarcomatous tumour were cut/separated and pushed into the vagina and removed later per vaginum. After removal of most of the sarcomatous growth, the uterus was found to be of small postmenopausal size and the growth seemed to be arising from the right cornua. Hysterectomy with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy was carried out in the usual manner. The cervical lips could not be well appreciated at the time of hysterectomy as they were completely effaced due to the large growth and the inversion.

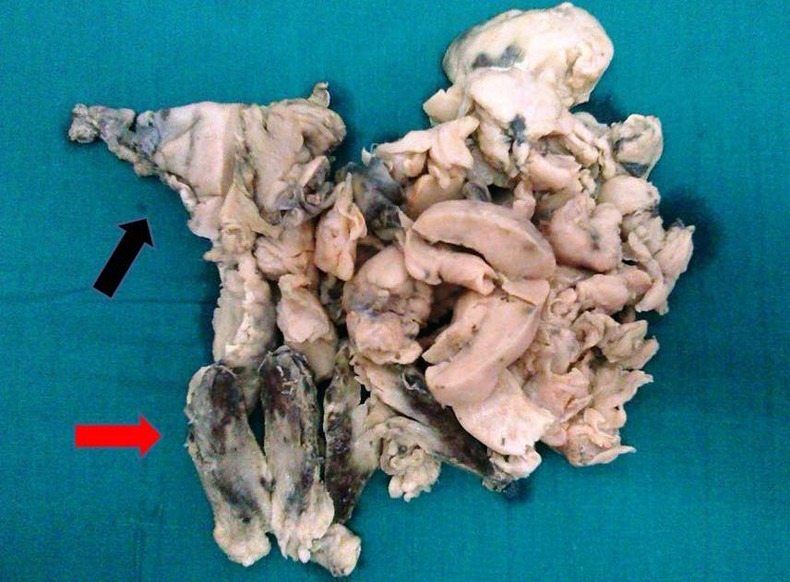

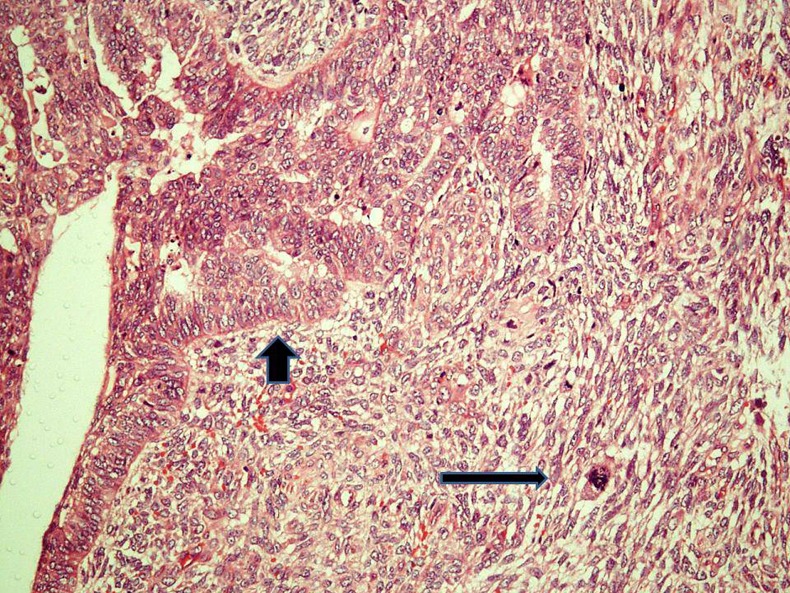

The total sarcomatous tissue when assembled together without the uterus measured 18×12×6 cm (figure 1). Histopathology revealed a tumour with biphasic appearance showing intimate admixture of carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements (figure 2). The carcinomatous component was endometroid glandular type. The sarcomatous component was of homologous type composed of round to spindle-shaped cells. Both the elements showed mitotic activity and atypical mitotic figures. Focal areas of haemorrhage and necrosis were seen. The invasion into myometrium was less than half. Cervix was involved by the tumour. Both the tubes and ovaries showed no pathological changes. The definitive diagnosis was thus given as malignant mixed mullerian tumour.

Figure 1.

Gross photograph showing uterus (black arrow) with multiple pieces of soft friable tumour with areas of haemorrhage and necrosis (red arrow).

Figure 2.

Photomicrograph showing a biphasic tumour with endometrioid type of carcinomatous component (short arrow) and a homologous sarcomatous component (long arrow; H&E, ×200).

Outcome and follow-up

The patient was discharged in a satisfactory condition on day 7. She received postoperative pelvic radiation. At the 9 months follow-up visit, however, she was found to have a 10×10 cm local pelvic recurrence. She was referred for palliative treatment to the radiotherapy department but was lost to follow-up thereafter.

Discussion

Acute inversion of the uterus is a life-threatening complication which usually occurs in the third stage of labour in which the uterus is turned inside out partially or completely. If untreated, uterine inversion can cause death, chronic uterine inversion, infection and very rarely even uterine sloughing. Non-puerperal chronic uterine inversions are rare and can be caused by benign (70%) or malignant tumours (20%).1 Fibroids have been described in some series to cause uterine inversion as they give a continuous drag at the fundus.2 Malignant mixed mesodermal tumours (MMMTs) or carcinosarcomas are even more uncommon since they are of rare occurrence (occur in 5% of all uterine tumours).3 4 They are bulky and would usually present as abnormal uterine bleeding or awareness of mass abdomen.

MMMTs are found predominantly in advanced age women as was our patient.3 4 Postmenopausal status, length more than 10 cm, cervical and peritoneal involvement carry a worse prognosis which were all present in our patient although peritoneal washings were negative and adnexa were free from disease.5 The status of the disease was at least of stage 2 in our patient due to involvement of the cervix. Lymphadenectomy was not carried out in our patient to avoid a prolonged surgery in light of her poor medical condition.

Histopathologically, MMMTs are divided into homologous or heterologous depending on the type of sarcomatous tissue.3 In our case, it was homologous of the spindle cell type. MMMTs are typically bulky, fleshier than adenocarcinomas, as was in our case. They have been associated with prolonged tamoxifen therapy, nulliparity or previous radiation though our patient had no such high risk factors.3 6 They usually present as vaginal bleeding and mass effect. An MMMT presenting as a uterine inversion is extremely rare and we could only find a few cases being reported.1 7 8 The only plausible explanation for this unusual presentation of inversion can be the rapid growth of a bulky mass originating at the fundus. An MRI or USG may suggest the diagnosis of inversion by showing the typically described U-shaped cavity or target appearance and pseudostripe, respectively.9 10 However, in our case, even though the clinical suspicion was high as the cervix was not felt per vaginum, a USG image was not suggestive and the bulky tumour (18 weeks uterine size) overstretched the inverted walls of the uterus to masquerade a large uterine heterogenous mass, though the cervix could not be appreciated.

A preoperative diagnosis of inversion is not always possible, and even if the clinical suspicion is high, definitive diagnosis would be known at the time of the surgery. Even in the case reported by Hanprasertpong et al,8 diagnostic laparoscopy was performed initially and then converted to a laparotomy. The reposition of the uterus and correcting the anatomy is vital before proceeding to hysterectomy. It would not be possible to separate and push down the bladder or clamp the uterine vessels for hysterectomy before repositing the uterus to its proper position. Reposition is difficult in view of the bulky malignancy (20 weeks in this case) invading the uterus. The tubes and ovaries were prolapsed into the constriction ring, putting the ureters also in danger. A combined abdominal and vaginal surgical approach may be required11 as in our case, that is, Haultain approach of excision of the cervical ring and excision of the pedicle performed via abdominal route followed by removing the prolapsed tumour vaginally. The preoperative biopsy helps to better plan a surgery and prognosticate the course of the disease.1 3 Our case is rare in its presentation and pathology and posed a diagnostic and surgical challenge to learn from.

Learning points.

Malignant mixed mullerian uterine tumour may present as uterine inversion in the postmenopausal patient.

Preoperative biopsy should be carried out for postmenopausal women presenting with bleeding and a uterine mass to better plan a surgery and prognosticate the disease.

The abdominopelvic surgical approach may be the best suited to remove large uterine carcinosarcomas with uterine inversion.

Footnotes

Contributors: RM and SS contributed to the write up. Pathological slides and legends were made available by RK. SA reviewed the write up.

Competing interests: None.

Patient consent: Obtained.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

References

- 1.Mwinyoglee J, Simelela N, Marivate M. Non-puerperal uterine inversions. A two case report and review of literature. Cent Afr J Med 1997;43:268–71 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Sharma JB, Kumar S, Rahman SM, et al. Non-puerperal incomplete uterine inversion due to large sub-mucous fundal fibroid found at hysterectomy: a report of two cases. Arch Gynecol Obstet 2009;279:565–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kanthan R, Senger JL. Uterine carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed müllerian tumours): a review with special emphasis on the controversies in management. Obstet Gynecol Int 2011;2011:470795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Banik T, Halder D, Gupta N, et al. Malignant mixed müllerian tumor of the uterus: diagnosis of a case by fine-needle aspiration cytology and review of literature. Diagn Cytopathol 2012;40:653–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Callister M, Ramondetta LM, Jhingran A, et al. Malignant mixed Müllerian tumors of the uterus: analysis of patterns of failure, prognostic factors, and treatment outcome. Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys 2004;58:786–96 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moe MM, El-Sharkawi S. Is there any association between uterine malignant mixed Mullerian tumour, breast cancer and prolonged tamoxifen treatment? J Obstet Gynaecol 2003;23:301–3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tjalma WA, Naik R, Monaghan JM, et al. Uterine inversion by a mixed müllerian tumor of the corpus. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2003;13:894–7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hanprasertpong J, Wootipoom V, Hanprasertpong T. Non-puerperal uterine inversion and uterine sarcoma (malignant mixed müllerian tumor): report of an unusual case. J Obstet Gynaecol Res 2004;30:105–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rana KA, Patel PS. Complete uterine inversion: an unusual yet crucial sonographic diagnosis. J Ultrasound Med 2009;28:1719–22 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lewin JS, Bryan PJ. MR imaging of uterine inversion. Comput Assist Tomogr 1989;13:357–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Moodley M, Moodley J. Non-puerperal uterine inversion in association with uterine sarcoma: clinical management. Int J Gynecol Cancer 2003;13:244–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]