Abstract

Objective

To determine feeding practices and selected health-related behaviours in New Zealand families following a ‘baby-led’ or more traditional ‘parent-led’ method for introducing complementary foods.

Design, setting and participants

199 mothers completed an online survey about introducing complementary foods to their infant. Participants were classified into one of four groups: ‘adherent baby-led weaning (BLW)’, the infant mostly or entirely fed themselves at 6–7 months; ‘self-identified BLW’, mothers reported following BLW at 6–7 months but were using spoon-feeding at least half the time; ‘parent-led feeding’, the mother reported not having tried BLW; and ‘unclassified method’, the mother reported they were not following BLW at 6–7 months but reported the infant mostly or entirely fed themselves at 6–7 months.

Results

8% were following ‘adherent BLW’, 21% ‘self-identified BLW’ and 0% were following the ‘unclassified method’. Compared with ‘self-identified BLW’ and ‘parent-led feeding’, a higher proportion of the ‘adherent BLW’ met the WHO recommendations to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months and to introduce complementary foods at 6 months. The ‘adherent BLW’ group was more likely to have family foods (p=0.018), and less likely (p=0.002) to have commercially prepared baby food. Both BLW groups were more likely to share meals with the family compared with ‘parent-led feeding’. In contrast to ‘self-identified BLW’ and ‘parent-led feeding’, the ‘adherent BLW’ group did not offer iron-fortified cereal as a first food.

Conclusions

This study suggests that although many parents consider they follow BLW, a very few are following it strictly. The extent to which BLW was followed was associated with potential benefits (eg, sharing family meals) and risks (eg, low iron first foods) highlighting the importance for health professionals and researchers of accurately determining the extent of adherence to BLW.

Keywords: NUTRITION & DIETETICS, Complementary feeding, Baby-Led Weaning

Strengths and limitations of this study.

This is the first study to investigate baby-led weaning in the general population.

The survey was advertised in main urban centres of New Zealand and may not be representative of rural families.

As the sample size is small, the results should be interpreted with caution.

Introduction

Baby-led weaning (BLW) is an alternative method for introducing complementary foods to infants in which the infants feed themselves hand-held foods instead of being spoon-fed by an adult.1 Unlike the traditional method of infant feeding where infants may be given finger foods alongside spoon-feeding, and in many countries their introduction is delayed to 7 or 8 months of age,2 3 BLW, in its purest form, does not include any spoon-feeding by the adult. The infant is only offered pieces of food, appropriately prepared, so that they can feed themselves.

Although anecdotal evidence suggests that BLW is becoming popular with parents, scientific research is limited to eight publications.4–11 The small body of existing research suggests that BLW is feasible for most 6-month-old infants from a motor development point of view.7 8 It also suggests that BLW is associated with potential benefits including lower levels of maternal anxiety, restriction, pressure to eat and monitoring during the complementary feeding period,4 and perhaps healthier eating patterns and body mass index.9 However, none of the studies to date have drawn their BLW cases and parent-led controls from the same population. Given the paucity of the current research and the lack of randomised controlled trials, healthcare professionals10 and health governing bodies12 are unwilling to support BLW as a population recommendation. Anecdotal reports suggest that the use of BLW is increasing in New Zealand (NZ) and other countries including the UK.

BLW in its strictest form requires that the infant has complete control over their own eating from the beginning of the complementary feeding period.1 In theory, BLW is therefore a distinctly different method of infant feeding compared with the traditional method of spoon-feeding purées.1 However, essential questions, such as how parents actually follow BLW in practice and the extent to which BLW is associated with health-related behaviours in the general population, remain unanswered.

The aim of this survey was to determine feeding practices and selected health-related behaviours in NZ families following ‘baby-led’ or more traditional ‘parent-led’ methods for introducing complementary foods.

Methods

Participants

Two hundred and thirty parents who had an infant aged 6–12 months were recruited from four main urban centres in NZ (Auckland, Wellington, Christchurch, Dunedin) by newspaper advertisement. The inclusion criteria were that participants had a healthy child aged 6–12 months who was born full term and was currently living in NZ, with no diagnosed neurological or developmental condition. Recruitment for the study stated that we were interested in when and how complementary foods were introduced to babies. To reduce selection bias, BLW was not mentioned. Advertisements for the study provided a web link to the online questionnaire.

Data collection

The population-based, cross-sectional survey was administered from May 2010 to August 2010 (3 months in total). The participants could complete the survey only once for one child. Consent and eligibility were established using check boxes that had to be completed before the participants were allowed entry to the survey.

The survey

The current survey questions were based on a web-based infant feeding survey previously administered in the UK,5 current infant nutrition literature, and consultation with a paediatrician, a paediatric dietitian and health researchers. The survey was designed and hosted using http://www.SurveyMonkey.com (SurveyMonkey Copyright 1999–2009). A pretest was electronically administered to 15 parents with young children aged 1–10 years to verify survey functionality and understandability and the survey was modified based on the pretesting results. The modifications included deleting a repeated question and rephrasing some questions to improve clarity.

The online survey was divided into four main sections (table 1 and box 1):

Starting complementary foods;

BLW;

Attitudes towards, and experiences of, feeding the infant;

Demographic information.

Table 1.

Overview of data collected in the survey

| Survey section | Data collected |

|---|---|

| Section 1: Starting complementary foods |

Timing and type of complementary food Participants were asked: Age (months) when the infant first had complementary food, main reason(s) for starting food at this age, the type of food given, form the food was in (puréed, mashed, whole), whether the food was homemade or commercially prepared. Mealtimes and eating patterns* Participants were asked: Frequency with which they ate with the infant (could have been different foods but baby ate at the same time), frequency infant ate family foods (could have been at a different time but they ate the same food that the rest of the family ate). Gagging and choking Many parents confuse gagging with choking or find it hard to differentiate between the two.13 We provided a written description before asking about gagging and choking. Participants were asked: If the child had ever gagged or choked and if so, how often, the form (purée, mashed, whole) of food that was involved, child's age when choked. |

| Section 2: BLW | Participants were asked: Had they tried BLW, the extent to which they had followed BLW, whether they would recommend the method to other parents. The participants who reported not having tried BLW were directed to questions asking their opinion of BLW based on a brief description (box 1) and short ‘introduction to BLW’ video, which was embedded in the survey. They were asked whether they would try BLW if they had another child and to provide reasons why they would or would not try it. |

| Section 3: Attitudes towards, and experiences of, feeding the infant | Participants were asked about their satisfaction with their choice of infant feeding method for the current infant, whether they would consider changing the feeding methods if they had another child, reasons for liking or disliking the method of feeding used. |

| Section 4: Demographic information | Participants were asked about age, sex, ethnicity, education, household, number of other children, employment status and region of New Zealand they lived in. |

*To obtain data for all infants at 6–7 months of age, parents were asked to answer questions relating to current age and also when the child was 6–7 months of age. Parents whose child was currently 6–7 months of age only completed this section once and then skipped to the following section.

BLW, baby-led weaning.

Box 1. Description of baby-led weaning included in the survey.

Traditional infant feeding involves offering the baby puréed foods first, then gradually increasing the texture from purée to mash, to lumpy and then to family foods. Baby-led weaning is different and involves the infants feeding themselves right from the start. You offer your baby pieces of soft food of a size and shape that the baby can handle (eg, steamed broccoli or carrots). The baby is allowed to explore the food at their own pace and they decide how much they will eat. Rather than preparing separate meals for your baby, they are offered foods similar to what the rest of the family is eating.

Data analysis

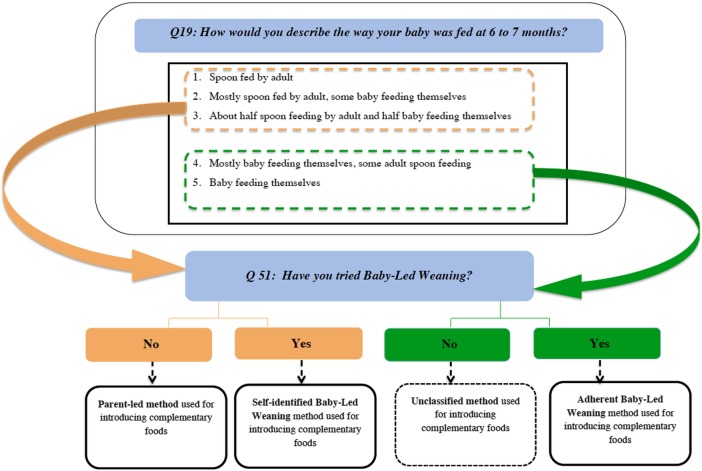

To compare those who considered themselves to be following BLW with those who met stricter criteria for BLW at 6–7 months of age we defined two BLW groups. Figure 1 shows the questions that determined which of the methods parents were considered to have used for introducing complementary foods.

Figure 1.

Survey questions used to classify infant feeding method.

The adherent BLW group consisted of those who reported having tried BLW and whose infant mostly or always self-fed at 6–7 months (figure 1). A broader definition of BLW was used to assign parents to the self-identified BLW group. These participants reported having tried BLW, but spoon-fed their infant at least half the time. All other participants who reported not having tried BLW were classified as either: (1) parent-led feeding (if they reported spoon-feeding their infant at least half the time), or (2) unclassified method (if they reported their infant mostly or always self-fed at 6–7 months). This group was named ‘unclassified’ as they were allowing their infant to self-feed (a key premise of BLW) but did not identify themselves as following BLW.

Information on ethnicity was collected using the 2006 NZ Census of Populations and Dwellings question as recommended by Statistics NZ.14 The participants who nominated two or more ethnic groups were assigned to a single group using the prioritisation system recommended by Statistics NZ, with the following order of priority (from highest to lowest): Māori, Pacific, Asian, Other and NZ European.14

Statistical analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata V.12 (STATA Corporation, College Station, Texas, USA). Descriptive statistics were tabulated and Pearson's χ2 tests and Fishers exact test (when cell counts were less than 10) were performed to examine the differences in proportions. A p value <0.05 was considered to indicate statistical significance. Characteristics, and feeding and health-related practices were compared across three groups: (1) ‘adherent BLW’, (2) ‘self-identified BLW’ and (3) ‘parent-led feeding’.

Results

A total of 199 participants completed the online survey (20 of the 230 people recruited did not meet the eligibility criteria and 11 people did not complete the entire survey). Most (n=140, 70%) of the sample were classified as ‘parent-led feeding’, 42 (21%) as ‘self-identified BLW’, 17 (9%) as ‘adherent BLW’ and 0 (0%) as ‘unclassified method’. Table 2 presents the participant characteristics. All participants who answered the survey were mothers. The mean age of the infants was 8.6 months. Approximately half of the mothers in the sample were 30–39 years of age, 66% had a tertiary qualification and 55% had more than one child. Maternal age (p=0.047; a greater proportion of mothers aged 20–29 followed ‘self-identified BLW’) and residing region (p=0.001; ‘adherent BLW’ was most likely among those living in Christchurch and least likely among those living in Auckland) were significantly associated with the feeding method. There were no other significant differences in participant characteristics between feeding methods (p≥0.05). Compared with recent national maternity data, the current sample had a higher proportion of NZ European (61% vs 55%), and a lower proportion of Māori (6% vs 20%) women.15 The sample also had a higher proportion of mothers with tertiary level education (66% vs 45%)16 and a lower proportion of single parents (23% vs 31%).17

Table 2.

Characteristics of participants

| All (n=199) | Parent-led feeding (n=140) | Self-identified BLW (n=42) | Adherent BLW (n=17) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Maternal age at child's birth (years) | 0.005 | ||||

| <20 | 13 | 11 (8.2) | 1 (2.4) | 1 (6.25) | |

| 20–29 | 49 | 28 (20.0) | 17 (40.5) | 4 (23.5) | |

| 30–39 | 103 | 71 (50.7) | 24 (57.1) | 8 (47.1) | |

| 40–49 | 28 | 24 (17.1) | 0 | 4 (23.5) | |

| Missing | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Infant age (months) | 0.194 | ||||

| 6–7 | 52 | 36 (25.7) | 13 (30.9) | 3 (17.6) | |

| 7–8 | 23 | 18 (12.9) | 2 (4.8) | 3 (17.6) | |

| 8–9 | 34 | 27 (19.3) | 5 (11.9) | 2 (11.8) | |

| 9–10 | 31 | 18 (12.9) | 12 (28.6) | 1 (5.9) | |

| 10–11 | 29 | 19 (13.6) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (29.4) | |

| 11–12 | 30 | 22 (15.7) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Maternal education | 0.572 | ||||

| Year 11 or below† | 6 | 3 (2.1) | 3 (7.1) | 0 | |

| Year 12 or 13‡ | 55 | 39 (27.9) | 11 (26.2) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Postsecondary school | 34 | 27 (19.3) | 5 (11.9) | 2 (11.8) | |

| University degree or higher | 98 | 65 (46.4) | 23 (54.8) | 10 (58.8) | |

| Missing | 6 | 6 | 0 | 0 | |

| Ethnicity | 0.966 | ||||

| NZ European | 121 | 78 (55.7) | 32 (76.2) | 11 (64.7) | |

| NZ Māori | 12 | 8 (5.7) | 4 (9.5) | 0 | |

| Samoan | 2 | 2 (1.4) | 0 | 0 | |

| Indian | 4 | 4 (2.9) | 0 | 0 | |

| Chinese | 2 | 1 (0.7) | 0 | 1 (5.9) | |

| English | 8 | 6 (4.3) | 2 (4.8) | 0 | |

| Other | 10 | 6 (4.3) | 3 (7.1) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Missing | 40 | 35 | 1 | 4 | |

| Parity | 0.240 | ||||

| Primiparous | 89 | 66 (47.1) | 14 (33.3) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Multiparous | 110 | 74 (52.9) | 28 (66.7) | 8 (47.1) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Household composition | 0.271 | ||||

| Mother and father | 160 | 115 (82.1) | 30 (71.4) | 15 (88.2) | |

| Single parent | 23 | 17 (12.1) | 6 (14.3) | 0 | |

| Missing | 16 | 8 | 6 | 2 | |

| Residing region | 0.001 | ||||

| Auckland | 78 | 61 (43.6) | 17 (43.6) | 0 | |

| Wellington | 42 | 28 (20.0) | 12 (28.6) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Christchurch | 29 | 17 (12.1) | 4 (9.5) | 8 (47.1) | |

| Dunedin | 31 | 21 (15.0) | 5 (11.9) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Other | 8 | 7 (5.0) | 1 (2.4) | 0 | |

| Missing | 11 | 6 | 3 | 2 | |

| Maternal employment status | 0.119 | ||||

| Currently in paid employment | 44 | 25 (18.7) | 15 (35.7) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Not in paid employment | 89 | 62 (46.3) | 21 (50.0) | 6 (35.3) | |

| On parental leave, returning to paid employment | 40 | 32 (23.9) | 5 (11.9) | 3 (17.6) | |

| On parental leave, not returning to paid employment | 18 | 15 (11.2) | 1 (2.4) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Missing | 8 | 6 | 0 | 2 | |

*p Value compares feeding methods, bold indicates significance.

†Year 11 is usually at age 15–16 years.

‡Years 12 and 13 are usually at ages 16–18 years.

BLW, baby-led weaning; NZ, New Zealand.

More than half (58%) of the sample surveyed exclusively breastfed their infant to 5 months of age, and only 4% reported never exclusively breastfeeding. However, 63% of infants received complementary food before the recommended age of 6 months. A greater number in the ‘adherent BLW’ group (53%) met the WHO recommendation to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months18 compared with the ‘self-identified’ (28%) and ‘parent-led feeding’ (21%) groups (p=0.026). Similarly, the number managing to meet the recommendation to introduce complementary foods at 6 months was significantly greater in the ‘adherent BLW’ group. A total of 65% in the ‘adherent BLW’ compared with the 33% in the ‘self-identified BLW’ and 34% in the ‘parent-led feeding’ group introduced complementary food at ≥6 months (p=0.044).

Table 3 summarises a range of feeding practices and health-related behaviours. Compared with the ‘self-identified BLW’ and ‘parent-led feeding’ groups, the ‘adherent BLW’ group was more likely to be having foods that the family ate (ie, the same food but not necessarily at the same time as the rest of the family; p=0.018), more likely to begin eating family foods when they started complementary foods or within the first month of starting (p<0.001) and were less likely to be offering their baby commercially prepared baby food (p=0.002). Both BLW groups were more likely to be sharing all or most of their meals with the family (ie, having meals at the same time but not necessarily the same food) compared with ‘parent-led feeding’ (p=0.040). In contrast to the ‘self-identified BLW’ and ‘parent-led feeding’ groups, ‘adherent BLW’ children were not offered infant iron-fortified cereal as their first food.

Table 3.

Feeding practices and health-related behaviours by feeding method used to introduce complementary foods

| All (n=199) | Parent-led feeding (n=140) | Self-identified BLW (n=42) | Adherent BLW (n=17) | p Value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |||

| Baby eats family food (may be modified or eaten at a different time) | 0.018 | ||||

| Doesn't eat family foods | 8 | 2 (1.4) | 6 (14.3) | 0 | |

| Occasionally | 150 | 113 (80.7) | 28 (66.7) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Most of the time or all of the time | 41 | 25 (17.8) | 8 (19.0) | 8 (47.1) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Age baby started eating family food | <0.001 | ||||

| When started CF or within 1 month | 20 | 7 (5.0) | 4 (9.5) | 9 (52.9) | |

| 2–4 months after starting CF | 68 | 50 (35.7) | 13 (31.0) | 5 (31.3) | |

| Doesn't eat with family | 111 | 83 (59.3) | 25 (59.5) | 3 (18.8) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Baby shares their meal with the family (even if food is different) | 0.040 | ||||

| None of their meals | 43 | 34 (24.2) | 7 (16.7) | 2 (11.5) | |

| Some of their meals | 90 | 67 (47.8) | 19 (45.2) | 4 (23.5) | |

| Most of their meals | 48 | 28 (20.0) | 12 (28.6) | 8 (47.1) | |

| All of their meals | 16 | 9 (6.5) | 4 (9.5) | 3 (17.6) | |

| Missing | 2 | 2 | 0 | 0 | |

| First food offered | 0.001 | ||||

| Baby rice cereal | 100 | 75 (53.6) | 24 (57.1) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Fruit | 70 | 48 (34.3) | 12 (28.6) | 10 (58.8) | |

| Vegetables | 29 | 17 (12.1) | 6 (14.3) | 6 (35.3) | |

| Meat | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Amount of commercially prepared baby food | 0.002 | ||||

| All of it | 14 | 11 (7.9) | 3 (7.1) | 0 | |

| Most of it | 34 | 21 (15.0) | 11 (26.2) | 2 (11.8) | |

| Half of it | 47 | 38 (27.0) | 8 (19.0) | 1 (5.9) | |

| Hardly any of it | 78 | 58 (41.4) | 15 (35.7) | 5 (29.4) | |

| None of it | 26 | 12 (8.6) | 5 (11.9) | 9 (52.9) | |

| Missing | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Reported a choking episode | 0.567 | ||||

| No | 130 | 95 (69.3) | 24 (60.0) | 11 (68.8) | |

| Yes | 63 | 42 (30.7) | 16 (40.0) | 5 (31.3) | |

| Missing | 7 | 3 | 2 | 2 | |

| Reported a gagging episode | 0.286 | ||||

| No | 51 | 39 (27.9) | 7 (16.6) | 5 (29.4) | |

| Yes | 143 | 99 (70.7) | 34 (81.0) | 10 (58.8) | |

| Missing | 5 | 2 | 1 | 2 | |

*p Value compares feeding methods, bold indicates significance.

BLW, baby-led weaning; CF, complementary foods.

Across the whole sample, 32.6% of participants reported at least one choking episode, and most (71.4%) of these participants reported that choking had occurred with whole food. There was no difference between groups for the proportion reporting at least one choking episode, the form (puréed, mashed or whole) that the food was in or the method of feeding (spoon-feeding or self-feeding) when the choking episode occurred (p>0.05). There was also no group difference in the proportion reporting at least one gagging episode (p>0.05).

Thirty-eight per cent of all participants had not heard of BLW, 7.6% reported knowing a lot about it and the remaining 54.1% reported knowing a moderate or small amount. A large proportion of the ‘parent-led feeding’ group had never heard of BLW (64.4%). The participants reported hearing about BLW through a friend or family member rather than from a healthcare professional.

All families who had followed BLW reported that they would recommend the method, but interestingly more than half (59.6%) would recommend that BLW be used in combination with spoon-feeding. Forty-six per cent of those who had followed ‘parent-led feeding’ would be willing to try BLW if they had another child. The main reasons reported for not wanting to try BLW were fear of their infant choking (55.3%), concern about the infant's ability to eat enough (44.2%), reservation that the infant would not have the necessary motor skills to self-feed (27.6%) or considering that ‘parent-led feeding’ had worked fine, so there was no need to change (27.1%).

Discussion

This is the first study to describe BLW and parent-led feeding in a sample from the general population. In contrast, the previous studies have recruited participants separately from BLW-specific groups or websites, with controls coming from other sources such as patient lists,9 and nurseries and community centres.4–6 We found that the association between infant feeding method and health-related behaviours differed depending on the extent to which families followed BLW. This indicates that it is essential for healthcare professionals, as well as researchers, to collect information on the extent of infant self-feeding when parents report following BLW. Compared with the ‘self-identified BLW’ and ‘parent-led feeding’ group, the ‘adherent BLW’ group were more likely to meet the WHO recommendations to exclusively breastfeed for 6 months, and to begin complementary foods at 6 months of age.18 The ‘adherent BLW’ group were also more likely to be having foods that the family ate, and were less likely to be offering their baby commercially prepared baby food. Both BLW groups were more likely to be sharing all or most of their meals with the family compared with the ‘parent-led feeding’ group. In contrast to the ‘self-identified BLW’ and ‘parent-led feeding’, children, ‘adherent BLW’ children were not offered infant iron-fortified cereal as their first food.

In this study, adherent BLW was defined as the baby feeding themselves all or most of the time at 6–7 months of age (ie, little or no parent spoon-feeding). The previous studies4 5 have defined BLW according to the extent of spoon-feeding and/or purées consumed. As our previous work10 had suggested that purées could be offered to the self-feeding infant (for instance puréed mince on toast) the definition used here related only to the method of feeding (self-feeding vs spoon-feeding) and not the form of food (purée, mashed or whole). In practice, only a small number of families (8% of this sample) were classified as following adherent BLW. A large proportion (21%) of families who reported using BLW was instead following a more flexible approach that included a combination of self-feeding and spoon-feeding. This agrees with our earlier qualitative study,10 in which families following BLW also reported using some spoon-feeding. Generally this occurred at times when their infant appeared unable to feed themselves (eg, during illness) or specifically to ensure appropriate iron intake (parents spoon-fed iron-fortified baby cereal at breakfast). This suggests that BLW and spoon-feeding are not viewed as dichotomous methods within the community but instead as styles of infant feeding that can be combined to suit the needs of the child and the family in each feeding situation.

A concern that is commonly expressed about BLW10 is the potential increased risk of choking when infants self-feed whole foods. In the period when infants transition from milk to solid foods they are at increased risk of choking because they may not have developed the coordination of chewing, breathing and swallowing needed to eat food safely.19 20 Choking is caused when the airway is obstructed and respiration is interrupted,21 and food-related choking can lead to death.20 22 Prevalence data on choking are limited, and no data exist on the rates of choking when complementary foods are being introduced, whether using the traditional or a BLW method. The most relevant data available show that in NZ in the period from 2002 to 2009, nine deaths occurred in children under 6 years of age as a result of the inhalation of food, specifically meat, sausage, peanuts, apple and grapes.22 In contrast, gagging, which is very common among all infants, is less serious.23 The gag reflex very effectively keeps large pieces of food well to the front of the mouth, only allowing well-masticated food to reach the back of the mouth for swallowing.1 24–26 In this survey, we found no difference between the groups in the proportion reporting at least one gagging or choking episode. However, more than 30% of the total sample reported at least one choking episode, and this most commonly involved whole foods. Since choking can be very serious it would be of concern if these reports reflect the actual choking rates. Parents often find it difficult to distinguish between choking and gagging, and therefore, although we included a definition of choking and gagging in our survey, it is likely that the parents have incorrectly identified choking, in particular mistaking gagging for choking. It is also important to note that because serious choking episodes are rare, this relatively small study was not powered to identify differences in these rates between the complementary feeding groups.

We found a number of important associations between the feeding method and the likelihood of achieving the nutrition recommendations for infants as outlined by the NZ Ministry of Health and WHO.3 18 The ‘adherent BLW’ group were more likely to meet the recommendation to exclusively breastfed to 6 months and to introduce complementary foods at 6 months. Two possible explanations for this finding are that the desire to follow BLW results in parents waiting until 6 months, which is the age when it is considered that most healthy infants are developmentally ready to self-feed,7 27 28 or that parents who choose BLW are more aware of and adhere to health recommendations. However, it is also feasible that parents who follow a parent-led method are able to encourage their infant to begin complementary foods earlier by feeding purées or infant cereal by spoon, which requires little input from the infant and therefore is not reliant on their developmental ability to actively participate in feeding. The results from the current study are consistent with a cross-sectional study from the UK where BLW (defined as less than 10% spoon-feeding or less than 10% purée use for total food intake) was associated with a later introduction of complementary foods.5 Furthermore, a UK-based survey examining the knowledge of infant feeding guidelines and the influence of healthcare professionals identified BLW as the strongest predictor for introducing complementary foods at the recommended age.29

The feeding method used by families was associated with many other potentially health-related behaviours. Those in the ‘adherent BLW’ group were most likely to offer fruits and vegetables as first complementary foods, and not iron-fortified cereal. It is of concern that for the ‘adherent BLW group’ the first foods reported in this survey were poor sources of iron, as this increases the infant's risk of suboptimal iron status.3 30–33 Although fruits and vegetables are nutrient-rich foods, they do not provide all the nutrients necessary for 6-month-old children.3 In particular, infants should receive iron-rich complementary foods such as meat, meat alternatives or iron-fortified foods immediately when starting complementary foods to supply necessary iron.3 30–33 We are unable to determine how long only fruit and vegetables were offered, and at what age iron-rich foods, such as meat, were introduced. However, spoon-feeding iron-fortified baby rice cereal is a popular way for parents to increase their infant's iron intake,3 and the semiliquid form of infant cereals makes them a difficult food for infants to feed themselves at 6 months. In this survey, none of the ‘adherent BLW’ group offered infant cereal as a first food. In contrast, some of the ‘self-identified BLW’ group did—presumably by spoon. Conversely, because the infant following BLW is eating family foods there may be a greater potential for a wider variety of iron-rich foods such as pieces of cooked red meat to be offered. The bioavailability of iron from these foods is also much higher (15.5%) than from infant cereals (3%).34 However, biochemical iron status was not determined in this study, hence we were unable to determine whether the risk of iron deficiency differed among the different complementary feeding groups.

Family meals have been linked to healthier eating patterns including greater intake of fruits and vegetables and lower intake of unhealthy foods.35–37 However, this relationship has been examined only in older children (2 years and over) and the benefits of family meals for younger children (ie, 6–12 months) are yet to be determined. Furthermore, no longitudinal studies have investigated whether the health benefits associated with sharing family meals track into later life. Besides the potential nutritional benefits associated with sharing family meals, there are other important reasons why infants should eat with the family, such as mealtimes providing an opportunity to communicate, learn and develop family rituals.38 Our results showed that the ‘adherent BLW’ parents were sharing a greater number of meals with their infant, and were likely to be doing this within 1 month of the initiation of complementary feeding. Brown and Lee6 reported similar results in their qualitative study. The results from the pilot study (n=10) of Rowan and Harris11 also showed that BLW families were sharing most meals (average of 3 of the 3.5 meals/day) with their child by 9 months of age.

In addition to sharing family meals, exposure to family foods (the same foods eaten by other family members) may encourage healthier long-term eating patterns.39–41 The results from a recent representative Scottish study showed that eating family foods was the most important aspect of family meals associated with a healthier diet at age 5 years (ie, it is the food choice that has greater importance than the form and function of the meal).42 In our survey, the ‘adherent BLW’ infants were having a greater amount of family foods, as well as less commercially purchased food, whereas the families who followed the ‘parent-led feeding’ method reported a greater proportion of commercially prepared food. While purchased baby food is nutritionally appropriate3 and many parents choose it for this reason, it is typically bland and of a smooth consistency. Only a longitudinal study would be able to determine the effects of early exposure to family foods compared with commercially prepared baby food on long-term dietary behaviours.

Most parents in the current study had either followed BLW or would be willing to try it with a subsequent child. All families who had followed BLW reported that they would recommend the method, but interestingly more than half would recommend that BLW be used in combination with spoon-feeding. Although more than one-third of the sample had not heard of BLW, after watching a short video and reading the brief description of BLW embedded in the survey, 46% reported being willing to try it with another child. Combining the parents who were willing to use BLW with those who reported already using it suggests that 79% of this sample would be willing to adopt, at least some aspects of, a baby-led approach, even though a large proportion had, prior to the survey, not heard of BLW. Those not willing to try BLW were concerned about choking, energy intake and developmental readiness of the infant to self-feed at 6 months or considered that the ‘parent-led feeding’ method had worked well for their family, precluding any need to change.

This study has a number of strengths and weaknesses. We attempted to improve the representativeness of our sample by advertising the study in public domains (particularly community distributed free newspapers). Recruiting participants from the general population instead of specific groups improves the likelihood of a more representative sample.43 44 We also avoided mentioning BLW in the advertisement to reduce the bias associated with recruiting only those familiar with BLW. However, as the survey was conducted through the Internet it required participants to have access to the Internet and possess computer skills. Recent figures show that 86% of NZ families have personal Internet access,45 suggesting that a large proportion could access the current survey. However, our newspaper advertising was restricted to urban areas and this may have affected our sample, as the demographic characteristics of the current sample do not reflect those of the general NZ population in some respects. In particular, the sample was highly educated with more mothers having a university degree (66%) compared with the general population (40%),46 and the rate of exclusive breastfeeding for 6 months (26%) was greater than that of the general population (16%).47 In addition, although we observed significant associations between the method used for introducing complementary foods and health outcomes, the direction of these associations cannot be determined due to the cross-sectional study design. This highlights the urgency with which prospective studies and randomised controlled trials of BLW are required so that the nature and direction of health-related associations can be firmly established. Therefore, as this study was relatively small (n=199), may have comprised participants who were more computer literate, and was cross-sectional, caution must be used when interpreting these results.

In conclusion, the majority of our sample was using the parent-led method of spoon-feeding purées to introduce complementary foods to their child. Twenty-one per cent of the sample reported using BLW but were not strictly limiting spoon-feeding, and a smaller number (8%) followed a strict BLW approach. We found several important associations between feeding method and health-related behaviours, suggesting that a greater adherence to the self-feeding tenet of BLW was associated with exclusively breastfeeding for 6 months, beginning complementary foods at 6 months, and eating the same foods as the rest of the family from the start of the complementary feeding period. However, it is concerning that these infants were not offered infant iron-fortified cereal as a first food. Both BLW groups were more likely to be sharing all or most of their meals with their family. The results of this study suggest that for many families the practice of BLW deviates substantially from the theory. It is therefore essential that health professionals, as well as researchers, do not rely on parental self-reports of BLW, but should also quantify the extent of infant self-feeding.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank all the families who contributed to this study.

Footnotes

Contributors: SLC, A-LMH and RWT were all involved with the conception and design of the study, analysis and interpretation of the data and writing and editing of this article. SLC designed and executed the online survey and was responsible for the analysis and interpretation of the data, wrote the first draft of the article, and A-LMH and RWT made important intellectual contributions to the content and approved the final version.

Funding: This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors. SLC was funded by a University of Otago PhD Scholarship.

Competing interests: None.

Ethics approval: Ethical approval was obtained from the University of Otago Ethics Committee, Dunedin, New Zealand.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data sharing statement: No additional data are available.

References

- 1.Rapley G, Murkett T. Baby-led weaning: helping your child love good food. London, UK: Vermilion, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 2.American Academy of Pediatrics Ages and stages: switching to solid food. 2008. http://www.healthychildren.org (accessed 6 Jun 2012)

- 3.New Zealand Ministry of Health Food and nutrition guidelines for healthy infants and toddlers (aged 0-2): a background paper. 4th edn Wellington, New Zealand: New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2008 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brown A, Lee M. Maternal control of child feeding during the weaning period: differences between mothers following a baby-led or standard weaning approach. Matern Child Health J 2011;15:1265–71 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brown A, Lee M. A descriptive study investigating the use and nature of baby-led weaning in a UK sample of mothers. Matern Child Nutr 2011;7:34–47 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brown A, Lee M. An exploration of experiences of mothers following a baby-led weaning style: developmental readiness for complementary foods. Matern Child Nutr 2013;9:233–43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wright CM, Cameron K, Tsiaka M, et al. Is baby-led weaning feasible? When do babies first reach out for and eat finger foods? Matern Child Nutr 2011;7:27–33 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cameron SL, Heath A-LM, Taylor RW. How feasible is baby-led weaning as an approach to infant feeding? A review of the evidence. Nutrients 2012;4:1575–609 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Townsend E, Pitchford NJ. Baby knows best? The impact of weaning style on food preferences and body mass index in early childhood in a case-controlled sample. BMJ Open 2012;2:e000298. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cameron SL, Heath A-LM, Taylor RW. Healthcare professionals’, and mothers’, knowledge of, attitudes to and experiences with, baby-led weaning: a content analysis study. BMJ Open 2012;2:e001542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rowan H, Harris C. Baby-led weaning and the family diet. A pilot study. Appetite 2012;58:1046–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.New Zealand Ministry of Health Baby-led weaning—ministry position statement. New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2010. http://www.health.govt.nz/our-work/preventative-health-wellness/nutrition/baby-led-weaning-ministry-position-statement (accessed 10 Oct 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Stratton SJ, Taves A, Lewis RJ, et al. Apparent life-threatening events in infants: high risk in the out-of-hospital environment. Ann Emerg Med 2004;43:711–17 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Statistics New Zealand Statistical standard for ethnicity. Statistics New Zealand, 2005. http://www2.stats.govt.nz/domino/external/web/carsweb.nsf/ (accessed 14 Jun 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 15.New Zealand Ministry of Health Maternity snapshot 2010: provisional data. New Zealand Ministry of Health, 2010. http://www.health.govt.nz/publication/maternity-snapshot-2010-provisional-data (accessed 4 Jun 2012) [Google Scholar]

- 16.OECD Education at a glance: OECD indicators. OECD Publishing, 2013. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/eag-2013-en (accessed 25 Jul 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 17.Statistics New Zealand Census snapshot: children. Statistics New Zealand, 2002. http://stats.govt.nz/browse_for_stats/people_and_communities/Children/census-snapshot-children.aspx (accessed 1 Mar 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 18.World Health Organization Infant and young child feeding: model chapter for textbooks for medical students and allied health professionals. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2009 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Byard RW, Gallard V, Johnson A, et al. Safe feeding practices for infants and young children. J Paediatr Child Health 1996;32:327–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Zigon G, Gregori D, Corradetti R, et al. Child mortality due to suffocation in Europe (1980–1995): a review of official data. Acta Otorhinolaryngol Ital 2006;26:154–61 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tarrago SB. Prevention of choking, strangulation, and suffocation in childhood. WMJ 2000;99:43–6, 42 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Child and Youth Mortality Review Committee Special report: unintentional suffocation, foreign body inhalation and strangulation. Wellington, New Zealand: Health Quality and Safety Commission New Zealand, 2013 [Google Scholar]

- 23.Arvedson J, Brodsky L. Pediatric swallowing and feeding: assessment and management. 2nd edn New York, USA: Singular publishing group, 2002 [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rapley G. Can babies initiate and direct the weaning process? Kent: Canterbury Christ Church University College, 2003 [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rapley G. Baby-led weaning: transitioning to solid foods at the baby's own pace. Community Pract 2011;84:20–3 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Rapley G. Talking about weaning. Community Pract 2011;84:40–1 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Northstone K, Emmett P, Nethersole F. The effect of age of introduction to lumpy solids on foods eaten and reported feeding difficulties at 6 and 15 months. J Hum Nutr Diet 2001;14:43–54 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Naylor A, Morrow A. Developmental readiness of normal full term infants to progress from exclusive breastfeeding to the introduction of complementary foods: reviews of the relevant literature concerning infant immunologic, gastrointestinal, oral motor and maternal reproductive and lactational development. Washington, DC: Wellstart International, LINKAGES Project Academy for Educational Development, 2001 [Google Scholar]

- 29.Moore AP, Milligan P, Goff LM. An online survey of knowledge of the weaning guidelines, advice from health visitors and other factors that influence weaning timing in UK mothers. Matern Child Nutr 201210.1111/j.740-8709.2012.00424.x [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Domellof M. Iron requirements in infancy. Ann Nutr Metab 2011;59:59–63 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Leong W-I, Lönnerdal B. Iron nutrition. In: Anderson G, McLaren G. eds. Iron physiology and pathophysiology in humans. New York, USA: Humana Press, 2012:81–99 [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kramer M, Kakuma R. Optimal duration of exclusive breastfeeding. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2002(1):CD003517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.World Health Organization Guiding principles for complementary feeding of the breastfed child. Geneva, Switzerland: World Health Organization, 2004 [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dube K, Schwartz J, Mueller MJ, et al. Iron intake and iron status in breastfed infants during the first year of life. Clin Nutr 2010;29:773–8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sen B. Frequency of family dinner and adolescent body weight status: evidence from the National Longitudinal Survey of Youth, 1997. Obesity 2006;14:2266–76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Utter J, Denny S, Robinson E, et al. Family meals among New Zealand young people: relationships with eating behaviors and body mass index. J Nutr Educ Behav 2013;45:3–11 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hammons AJ, Fiese BH. Is frequency of shared family meals related to the nutritional health of children and adolescents? Pediatrics 2011;127:e1565–74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Story M, Neumark-Sztainer D. A perspective on family meals: do they matter? Nutr Today 2005;40:261–6 [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hetherington MM, Cecil JE, Jackson DM, et al. Feeding infants and young children. From guidelines to practice. Appetite 2011;57:791–5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Skinner JD, Carruth BR, Bounds W, et al. Do food-related experiences in the first 2 years of life predict dietary variety in school-aged children? J Nutr Educ Behav 2002;34:310–15 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Harris G. Development of taste and food preferences in children. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care 2008;11:315–19 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Skafida V. The family meal panacea: exploring how different aspects of family meal occurrence, meal habits and meal enjoyment relate to young children's diets. Sociol Health Illn 2013;35:906–23 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tripepi G, Jager KJ, Dekker FW, et al. Selection bias and information bias in clinical research. Nephron Clin Pract 2010;115:c94–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ellenberg JH. Selection bias in observational and experimental studies. Stat Med 1994;13:557–67 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Bell A, Gibson A, Crothers C, et al. The internet in New Zealand 2011. Auckland, New Zealand Institute of Culture, Discourse & Communication, AUT University, 2011 [Google Scholar]

- 46.Statistics New Zealand QuickStats about education and training. Statistics New Zealand, 2006. http://www.stats.govt.nz/Census/2006CensusHomePage/QuickStats/quickstats-about-a-subject/education-and-training.aspx (accessed 28 May 2013) [Google Scholar]

- 47.Royal NZ Plunket Society Breastfeeding data. Analysis of 2004–2009 data. Wellington: Royal NZ Plunket Society, 2010 [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.