Abstract

Aim

This paper describes our experience of 20 cases identified in the FEA vacuum core biopsy.

Background

Screening mammography has contributed to the increased recognition of early cancer, premalignant and preinvasive breast lesions. A premalignant lesion called FEA (flat epithelial atypia), although rarely recognized as the only lesion in the core biopsy, is a major challenge in clinical proceedings. Increasing recognition is associated with an increasing use of the vacuum core biopsy as a tool for verifying nonpalpable lesions identified by mammography, and suspected of being breast cancer.

Materials and methods

Of 4326 mammotome biopsies performed at our institution in 2000–2006, FEA was diagnosed in 20 patients (0.46%). These patients underwent surgery for reexcsion. Data were collected for clinical, radiological and pathological findings to assess factors associated with the underestimation of invasive lesions.

Results

Among 20 patients with FEA diagnosis, the mean age was 59.6, range 52–71. When compared to the ADH group (mean age 55.45), the FEA patients were found to be statistically significantly older (p = 0.0002). Two patients 2/20 (10%) showed underestimation, with invasive cancer on the final pathology were G1 tubular cancer T1b, and G2 lobular cancer T1a.

Conclusion

Although FEA is rarely diagnosed as the only lesion in a core biopsy, the ever more common use of this diagnostic technique forces us to establish a clear clinical practice. The problem is the underestimation of invasive lesions in the case of primary diagnosis of FEA. It seems that some percent of these cases can be identified by certain radiological or pathological features, thus helping implement appropriate clinical management.

Keywords: Flat epithelial atypia, Breast cancer, Core needle biopsy

1. Background

In 1979, Azzopardi described intraepithelial neoplasia which he called “clinging carcinoma in situ”.1 She regarded the lesion as a variant of DCIS (ductal carcinoma in situ), which is easy to overlook in histopathology, and is due to cellular rather than architectural changes. Currently, FEA is the earliest, morphologically recognizable neoplastic lesion in the breast. It is characterized by medium to large cellular atypia epithelial single layer of cells. The degree of cellular atypia should be a determinant of the division of FEA into 2 groups – a high (pleomorphic variant) and a low degree of atypia (monomorphic variant). Azzopardi suggested new type of DCIS as 1, 2 or more layers of atypical cell lines without the presence of intraepithelial proliferation. It differs from the CCC (columnar cell changes) in the presence of cellular atypia, and from the ADH (atypical ductal hyperplasia) in the existence of a comprehensive architectural atypia. Over the years, the importance of recognizing clinging DCIS has been a matter of discussion. Only results of molecular level research showed the association between this early neoplastic change and invasive breast cancer.2 A link was also shown between lobular and tubular cancer and changes in the type of clinging. In the course of years, many different terms have been used to describe the lesion. At present, two names are used – flat epithelial atypia, or flat DIN (ductal intraepithelial neoplasia) – DIN1 (in accordance with the guidelines of the WHO classification of 2003).3 Patients who are diagnosed with FEA are just a few years younger than the group with ADH (an average of 44–51 years versus an average of 54 years in the case of ADH).4–8 The most common radiographic presence of FEA are microcalcifications.9 They occur in approximately 74% of patients with FEA.10 Observed ultrasound, they present a poorly demarcated nodular mass with irregular shape, sometimes with arched or spicular border.9 The aim of this study is to evaluate the underestimation of invasive lesions after the initial diagnosis of FEA in mammotome vacuum core biopsy.

2. Materials and methods

Retrospectively analyzed 20 patients with a primary diagnosis of FEA on the basis of mammotome vacuum assisted 11 gauge core needle biopsies. A biopsy was performed in the mammtome biopsy outpatient clinic in the Department of Surgical Oncology and General Surgery, Wielkopolska Cancer Centre. For six and a half years, 4326 biopsies were done. Biopsies were performed in patients with nonpalpable breast lesions. In other cases, ultrasound-guided core needle biopsies were performed (this group of patients is not the subject of the present study). Mammotome biopsy was performed on the table, where patients were turned to face downwards (Fisher Imaging, Denver, CO, USA) using 11 gauge directional vacuum assisted biopsy systems (Mammotome Biopsy/Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Cinncinatti, OH). They obtained an average of 12 cores (from 7 to 30). Biopsies were performed by three oncological surgeons. In most cases, patients were referred with a suspicious mammogram image detected in a nationwide screening program. Patients with diagnosis of FEA were treated surgically by excision of the area where FEA was diagnosed. In the case of finding the cancer re-excision if no clear margins were found was performed together with sentinel node biopsy for axillary nodal staging. For all cases, pictures and descriptions of mammography, or ultrasound data were collected for review (Figs. 1 and 2). The patients were re-examined and verified for clinical data such as age, oncological history, family burden, mammography, concomitant benign lesions of the breast, type of operation.

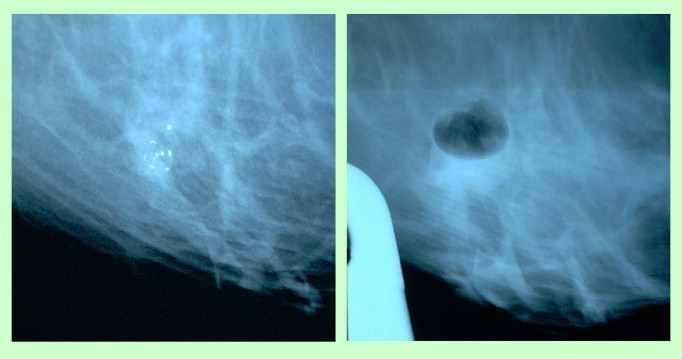

Fig. 1.

View on the mammotome monitor-microcalcifications before and after biopsy.

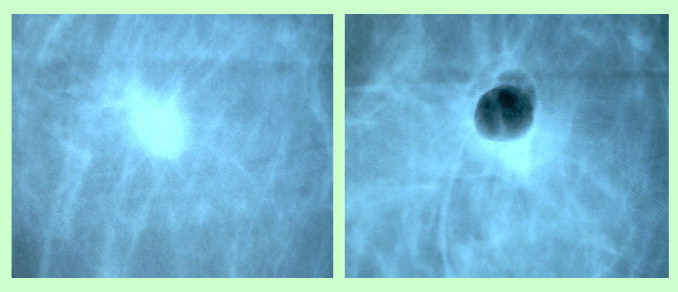

Fig. 2.

Tumor mass before and after biopsy.

3. Results

Among 20 patients with FEA diagnosis a mean age was 59.6, ranging from 52 to 71. When compared to the ADH group (mean age 55.45), the FEA patients are found to be statistically significantly older (p = 0.0002). The two patients showed underestimation 2/20 (10%) with invasive cancer on final pathology. Two patients with invasive cancer on the final pathology were G1 tubular invasive cancer T1b, and G2 lobular invasive cancer T1a. After lymph node sampling, only the lobular cancer patient showed lymph node metastasis in one node. Radiological features showed tumor mass in 7 patients, density in 2 patients, and microcalcifications in 11 patients. Underestimated patients had tumor mass and density. From the pathological point of view, concomitant benign features were observed: adenosis sclerosans in 4 patients, fibrosis in 1 patient, mastopathia fibrosa in 8 patients, mastopatia cystica in 5 patients, adenosis microglandularis in 3 patients. Underestimated patients did not show concomitant pathological features.

4. Discussion

Discovering suspected microcalcifications detected at screening mammography leads to diagnosis by stereotactic core needle biopsy. Currently, we can use stereotactic or ultrasound-guided core needle biopsy for many different breast lesions.10,11 In case of the FEA, cancerous lesions of the breast should be searched. In addition to problems related to the very procedure of biopsy, destruction of specimens and a small amount of tissue collected at biopsy, we must also handle with its twisting, or crushing. All this makes it difficult to adequately assess results of histopathological examination. Owing to the use of thicker biopsy needles (11 G instead of 14 G), greater number of biopsy fragments retrieved, and the routine use of radiographs of collected tissue fragments, the accuracy of microscopic examination has improved. There are still no clear guidelines for the diagnosis of FEA in the stereotactic biopsy. In only a few studies in small numbers of patients lesions of invasive and preinvasive pattern occurred in 13–30% of cases.8,12–17 DCIS and LN (lobular neoplasia) were present along with FEA in 22–36% of cases.18 In the study by Guerra-Wallace et al. describing the frequency of coexistence of tumor diagnosis in the case of intraductal hyperplasia (Columnare cell lesions) on the basis of core biopsy, the final excision was followed by a higher incidence of tumor in the group with atypia (FEA-11/60–18%) compared to patients without atypia – (UDH 10/135–7%).14 The report by Bonnet et al., nine cases with FEA were found in 167 biopsies. Of these patients, two were detected to have DCIS, and three ADH (atypical ductal hyperplasia) after radical surgery.12 In the paper by Kunju and Kleer, out of 14 patients diagnosed with FEA in core biopsy (14 G), after surgical excision of the lesion, one was found to show concomitant DCIS, and in two cases invasive cancers were detected.8 Underestimation of invasive lesions amounted to 21%. It should also be noted that in other five cases (36%) ADH was found, and LN and in one case (8%). Usability testing of Ki-67 has been demonstrated as negative, because regardless of whether additional clusters were found cancerous or not, the results were similar.15 It is important to demonstrate the presence of chronic inflammation (29%) and stromal changes (36%), such as myxoid changes and periductal fibrosis, which are associated with FEA. The study by Piubello et al. reported 875 patients who underwent core biopsy (11 G). 33 cases were diagnosed with FEA.17 None of these patients showed concomitant cancer after surgical excision. However, in the case of coexistent FEA and ADH found in 11 patients, underestimation of cancer was 30%. In the study by Chivukula et al. on a group of 35 patients diagnosed with FEA, underestimation of the tumor was 14%, while in the presence of FEA together with ADH underestimation was 16.3%.13 There was no statistical significance between the underestimation of cancer in the group with FEA, FEA + ADH and ADH alone.13 In the study by Lim et al. on five patients with CCL and atypia, in one (20%) DCIS lesion were found after surgical excision.19 Labbe-DeVilliers et al. described two subgroups of patients: CCH with atypia – 25 cases, CCC with atypia – 15 patients.20 Invasive lesions were diagnosed in 4 patients (10%), and DCIS in 3 (8%), accounting for a total underestimation of the tumor of 18%. All tumors were found in the group of CCH with atypia. If the CCC with atypia in mammography images outbreak was less than 10 mm, there was no concomitant cancer changes. In the study by de Mascarel et al. on the basis of 2833 biopsies due to suspected microcalcifications, FEA was found in 101 patients.21 Underestimation of the tumor occurred in 17 of them (17%). Among the concomitant cancers were 12 cases of DCIS or invasive ductal cancer, four cases of tubular cancer and one of lobular carcinoma. In our study, FEA was diagnosed in 20 patients, representing 0.5% of all cases diagnosed in the mammotome biopsy. Studies with a percent of underestimation in the case of FEA diagnosis are summarized in Table 1. Underestimation of invasive lesions occurred in two patients (10%), both diagnosed with invasive cancer. There was a significant difference in age between the group of patients with the diagnosis of FEA and a group with a diagnosis of ADH, where the average age in the FEA group was 59.6 years and versus 55.45 years in the ADH group. It is in opposition to other results where patients with more advanced pathological findings, like ADH, are statistically older than FEA patients.4–8 The reason for this finding in our population is unclear, but probably can be accounted for by a small number of patients diagnosed with FEA. The question of eligibility of patients for radical removal of the lesion remains unresolved. Does the complete removal of microcalcifications due to core biopsy eliminate the need for surgical resection of the area? Will greater amount of tissue collected during biopsy allow for close observation of patients, instead of surgery? According to Ho et al., even total resection of an area of microcalcifications in the case of ADH is associated with a 17% underestimation of invasive cancer.7 In the case of FEA, the risk may be the same. Magnetic resonance might be a useful tool in diagnosis of premalignant lesions. But additional research is required on the usefulness of this test. We should also consider better information for the patient as well as support, especially in the case of increased risk of breast, cancer in the future.22

Table 1.

Underestimation of a cancer in case of FEA diagnosis.

| Study | Number of patients with FEA | Underestimation of a cancer |

|---|---|---|

| Guerra-Wallace et al. | 60 | 11 (18%) |

| Bonnet et al. | 9 | 2 (22%) |

| Kunju and Kleer | 14 | 3 (21%) |

| Piubello et al. | 33 | 0 |

| Chivukula et al. | 35 | 5 (14%) |

| Lim et al. | 5 | 1 (20%) |

| Labbe-DeVilliers et al. | 40 | 7 (18%) |

| Mascarel et al. | 101 | 17 (17%) |

| Current study | 20 | 2 (10%) |

Conflict of interest

None of the Authors have a conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Azzopardi J.G. Clining carcinoma. In: Azzopardi J.G., Ahmed A., Millis R.R., editors. Problems in breast pathology. Saunders Co. Ltd.; Philadelphia: 1979. pp. 193–203. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Moinfar F., Man Y.G., Bratthauser G.L. Genetic abnormalities in mammary ductal intraepithelial neoplasia-flat type (clinging ductal carcinoma in situ) a simulator of normal mammary epithelium. Cancer. 2000;88:2072–2081. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tavassoli F.A., Hoefler H., Rosai J. Intraductal proliferative lesions. In: Tavassoli F.A., Devilee P., editors. Pathology and genetics tumors of the breast and female genital organs. IARC Press; Lyon: 2003. pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eusebi V., Betts G., Haagensen D.E., Jr. Apocrine, differentiation in lobular carcinoma oft he breast: a morphologic, immunologic, and ultrastructural study. Hum Pathol. 1984;15(2):134–140. doi: 10.1016/s0046-8177(84)80053-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Eusebi V., Feudale E., Foschini M.P. Long term follow up of in situ carcinoma of the breast. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1994;11:223–235. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eusebi V., Foschini M.P., Cook M.G. Long term follow up of in situ carcinoma of the breast with special emphasis on clinging carcinoma. Semin Diagn Pathol. 1989;6:165–173. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho B.C., Tan P.H. Flat epithelial atypia: concepts and controversies of an intraductal lesion of the breast. Pathology. 2005;37:105–111. doi: 10.1080/00313020500058532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kunju L., Kleer C. Significance o flat epithelial atypia on mammotome core needle biopsy: should it be excised? Hum Pathol. 2007;38:35–41. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2006.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kim M.J., Kim E.K., Oh K.K., Park B.W., Kim H. Columnar cell lesions of the breast: mammographic and US features. Eur J Radiol. 2006;449:609–616. doi: 10.1016/j.ejrad.2006.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fraser J.L., Raza S., Chorny K., Connolly J.L., Schnitt S.J. Columnar alteration with prominent atypical snouts and secretions: a spectrum of changes frequently present in breast biopsies performed for microcalcifications. Am J Surg Pathol. 1998;22:1521–1527. doi: 10.1097/00000478-199812000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Polom K., Murawa D., Nowaczyk P. Vacuum-assisted core-needle biopsy as a diagnostic and therapeutic method in lesions radiologically suspicious of breast fibroadenoma. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2011;16:32–35. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2010.12.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bonnet M., Wallis T., Rossmann M. Histologic analysis of atypia diagnosed on needle core breast biopsies. Mod Pathol. 2002;15:29. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chivukula M., Bhargava R., Tseng G., Dabbs D.J. Clinicopathologic implications of “flat epithelial atypia” in core needle biopsy specimens of the breast. Anat Pathol. 2009;131:802–808. doi: 10.1309/AJCPLDG6TT7VAHPH. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guerra-Wallace M.M., Christensen W.N., White R.L. A retrospective study of columnar alteration with prominent apical snouts and secretions and the association with cancer. Am J Surg. 2004;188:395–398. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2004.06.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lara J.F., Young S.M., Velilla R.E. The relevance of occult axillary micrometastasis in ductal carcinoma in situ: a clinicopathologic study with long-term follow-up. Cancer. 2003;98:2105–2113. doi: 10.1002/cncr.11761. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Martel M., Barron-Rodriguez P., Tolgay Ocal I. Flat DIN 1 (flat epithelial atypia) on core needle biopsy: 63 cases identified retrospectively among 1751 core biopsies performed over an 8-year period (1992–1999) Virchows Arch. 2007;451:883–891. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0499-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Piubello Q., Parisi A., Eccher A., Barbazeni G., Franchini Z., Iannucci A. Flat epithelial atypia on core needle biopsy. Which is the right management? Am J Surg Pathol. 2009;33(7):1078–1084. doi: 10.1097/PAS.0b013e31819d0a4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oyama T., Iijima K., Takei H. Atypical cystic lobule of the breast: an early stage of low grade ductal carcinoma in situ. Breast Cancer. 2000;7:326–331. doi: 10.1007/BF02966399. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lim C.N., Ho B.C.S., Bay B.H., Yip G., Tan P.H. Nuclear morpholometry in columnar cell lesions of the breast: is it useful? J Clin Pathol. 2006;59:1283–1286. doi: 10.1136/jcp.2005.035428. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Labbe-Devilliers D.N., Moreau C., Loussouarn D., Campin L. Diagnosis of flat epithelial atypia after stereotactic vacuum-assisted biopsy of the breast: what is the best management: systematic surgery for all or follow up? Clin Imaging. 2007;31:220–223. doi: 10.1016/s0221-0363(06)74145-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.de Mascarel I., MacGrogan G., Mathoulin-Pellisier S., Vincent-Salomon A., Soubeyran I., Picot V. Epithelial atypia in biopsies performed for microcalcifications. Practical consideration about 2833 serially sectioned surgical biopsies with a long follow-up. Virchows Arch. 2007;451:1–10. doi: 10.1007/s00428-007-0408-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bernad D., Zysnarska M., Adamek R. Social support to oncological patients—selected problems. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2010;15(2):47–50. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2010.02.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]