Abstract

Background

The essence of psychological support provided to oncology patients is to adjust its methods to the needs and expectations arising from the distressful experience of cancer and its treatment.

Aim

The aim of this study is to present methods of professional psychological support to be used in work with oncology patients during the treatment and follow-up stages.

Materials and methods

The article is a review of psychological and psychotherapy methods most often applied to oncology patients.

Conclusion

Methods of psychological support depend on the current condition of a patient. The support will be effective if provided in adequate time and place with the patient's express consent and in line with their individual needs and expectations.

Keywords: Psychology, Psychological support, Psycho-oncology

1. Background

Never in our lives do we need assistance and presence of another person more than we do in the time when death is nearby, fear is paralysing while we have a strong desire to live.1

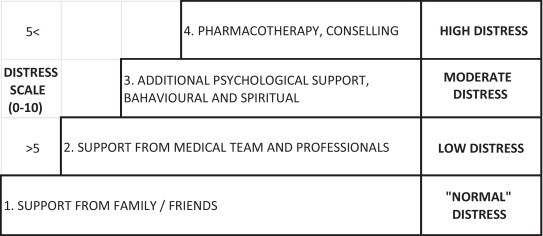

Cancer is one of the most difficult experiences in human life, causing many adverse changes. These changes relate to physical effects (pain, weakening, fatigue, change in appearance, etc.) and mental status (anxiety, fear, sorrow, despair), concerns about living conditions, existential and spiritual dilemmas arising from the disease and its treatment, which is often a long-standing and burdensome experience for the patient and their family and friends.2,3 The extent and intensity of those factors may put oncology patients into distress. Whether and what kind of support a patient needs and expects may be determined by diagnosing the degree of distress which may differ with successive stages of disease and treatment (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Degrees of distress: procedure compliant with ASCO standards and guidelines (based on the WHO analgetic scale), see: Winch B., Cancer progression rate and psychological aid [in Polish].

Professional support for oncology patients is one of the tasks of a psychologist's work. The specific nature of this support arises from the complexity of the condition a patient affected by cancer and its treatment is in. Extreme emotional responses may be evoked by other immediate or delayed side effects, related to radiotherapy, but also surgical treatment or chemotherapy, even if patients have been informed of their possible occurrence. The state of distress leads to patients’ informational and emotional disarray, disrupts their internal and external harmony or deepens a crisis existing prior to the disease. The side effects include: dermal lesions, nausea, changes in diet, weakening of the immunity system caused by reduced levels of white cells and blood platelets, decreased interest in sexual activity, loss of hair, gum oedema, xerostomia, increased dental defects, muscular stiffening. They depend not only on the treatment area and dose, but also on patient's individual reactions. The psychologist dealing with this category of patients should take into account that these effects, while deteriorating patients’ quality of life, affect their cognitive, emotional, and psycho-social functioning, as well as activate their defensive mechanisms, thus exerting an impact on their interpretation of the situation they are in. Consideration should also be taken to co-occurrence of other somatic or mental diseases and personal problems, not necessarily induced by cancer (being prior to or independent of the disease and treatment) and yet showing some feedback correlation with it.4

Having reviewed patient's status, the psychologist may try to identify objectives of psychological support to be provided for oncology patients during irradiation or follow-up, as these help determine which of many forms or methods to select for the patient or group of patients.5,6

Therefore, the variety of stages and objectives has to be accompanied by varied forms of psychological impact (as discussed in detail below):

-

•

psychological counselling;

-

•

crisis interventions;

-

•

rehabilitation;

-

•

prevention and health promotion;

-

•

psychotherapy.7

Work with oncology patients, including those treated with irradiation, requires from a psychologist not only to have a very good knowledge of the psychology of somatic patients, elements of general medicine, oncology, and radiotherapy, but also to show realistic optimism, respect for all stages of human life and readiness to help.4

It needs to be added, however, that the relationship of trust depends also on the attitude of the assisted person (helping is an interaction between the one who helps and the one who is helped plus external factors including: their self-image and self-confidence, often degraded by mutilating surgeries, the need to give up work, loss of hair and other side effects, overall trust in people, interpretation of psychologist's behaviour and negative self-perception (perceived image of the disease), individual ability to cope with the stress of the disease). This attitude may also be affected by seemingly insignificant elements of the setting: quality and comfort of the place where support is given, its decor and peace.8

2. Aim

It is well known that modern hospital treatment, in the age of advanced medical techniques and improved health care, is limited to necessary minimum. Therefore, methods of psychological support will be discussed only in those aspects where they are relevant for psychological interventions in inpatient and outpatient health care.

3. Theoretical background

3.1. Crisis intervention

Cancer is one of many crisis situations.9 Anybody can be affected by it, therefore, it can be looked upon as a threat. However, it should also be remembered that it offers an opportunity for a change. A person experiencing this condition and related emotions and feelings requires external support as they have run out of resources to cope with the problem on their own.

Crisis intervention is a form of assistance in sudden, surprising and disintegrating life events. Cancer is such kind of an event for many people, particularly in the following turning points:

-

•

when it is identified (diagnosed);

-

•

when treatment proposal, particularly operative, is given by a doctor;

-

•

in the case of a relapse (recurrence, metastasis), particularly if occurring after a long period of stability and recovery to normal life10;

Each of the above circumstances may call for a rapid, urgent psychological support (but also interdisciplinary aid including medical, nursery, social, legal, etc.). The intervention in such a case involves:

-

•

support for the patient and their family by building a good relationship, listening to their stories, encouraging them to express feelings openly;

-

•

help in making the patient understand the situation by explaining their doubts;

-

•

suggesting specific measures (e.g. additional doctor consultation; addressing an aid organisation, self-support association or disability centre; calling a voluntary social worker; reconsidering the decision to quit treatment, etc.);

-

•

building the patient's hope by showing perspectives for the nearest future (week, month).10

The fastest and most effective forms of intervention will be identified depending on the patient's individual situation, emotional status and coping. The assessment has to be adequate and prompt to prevent the patient from stepping back and isolating themselves from the disease. Such attempts at alienating oneself from cancer (manifested with the mechanism of negation, rejection of support) are immediate reactions to the diagnosis or decision to treat which are likely to bring tragic consequences (delay in treatment, losing chances for recovery or longer survival). It is clear then that time is a critical factor both for the patient and, indirectly, for the interventionist. It should be stressed, though, that a day of delay may sometimes be helpful by allowing a peaceful reflection, winning patient's approval or support from the family, a medical professional or a psychologist. A short delay may be rewarded with patient's coming to terms with their disease, which, in turn, may be a turning point to start treatment and fight for recovery.10

3.2. Psychological counselling

Psychological counselling is a form of support offered to individuals experiencing developmental crisis or adaptive difficulties.7

Developmental crises occur whenever new challenges appear in a person's life involving a natural process of entering into a new stage of life. They turn up when the person is not yet capable of coping with the challenges assigned to the stage they are entering, when they have not yet learnt to meet their new needs (e.g. in the periods of adolescence, maturity, middle-age or seniority and their respective developmental tasks upon performance of which a new stage begins, e.g.: building one's identity, sexual needs, desire for closeness, new parental roles, challenges related to work and professional career, change of parental roles with adult children, poor health performance, retirement).

In the course of life, one experiences varied circumstances. Among them are unexpected moments of joy or sorrow, such as falling in love or learning about one's own or/and beloved person's cancer. Such circumstances, especially if occurring unexpectedly, may give rise to anxiety and prevent one from using the otherwise effective ways of coping with trouble or be so different from earlier experiences as to require new strategies to tackle the crisis.

A developmental change or the accumulation of distressful life events or both of these at the same time (e.g. disease diagnosed in a patient entering the stage of adolescence, a divorce taking place soon after a mutilating mastectomy due to a diagnosed breast cancer) may require advice from a person who is able to look at the situation with an objective eye. This is a good time for psychological counselling which involves several interviews aimed to identify a problem and find a solution.

3.3. Self-support groups – clinical psychologist as a problem consultant, self-support group expert

Self-support groups play an important role in health care by providing peer assistance in solving common personal and social problems. A set of conditions has to be met for each group to start and continue its activity: voluntary membership, common problems, advice giving, altruism, self-identity, hope raising, group cohesion.7

One of the types of self-support groups comprises people living under a heavy, long-standing stress. Groups of this type have the objective to create proper conditions for their members so as to give vent to their emotions, find emotional support, share their experiences of coping with difficulties showing that this is possible. This category includes oncology patients: post-mastectomy women (Amazonki), persons after stoma surgery (POL-ILKO), etc. Members of those groups, apart from emotional support, help one another in obtaining important information, equipment, medicines, etc.7

In such groups, psychologists play the role of consultants or experts, but their task is also to provide persons at all stages of treatment and follow-up with information on opportunities7 of joining a self-support group (which very often marks the beginning of the process of revaluating the disease from a death sentence to a gift of a second better life). Psychologists often cooperate with volunteers from patient associations by inviting them to meetings with persons who have to cope or will have to cope with similar experiences of disease, mutilating surgery, difficult recovery or return to everyday life (Amazonki, Kwiat Kobiecości, POLiKO, Gladiator, Sowie Oczy, etc.).7

3.4. Clinical psychological support for disabled persons suffering from cancer or persons who have become disabled due to cancer treatment – psychological rehabilitation

Ever since its introduction, rehabilitation psychology has been an interdisciplinary and complex field. Disability may result from body defects (biological structures) or effects of a disease (including cancer) and involve physical and/or mental dysfunction in satisfying one's needs and meeting social requirements.

Psychologists are more interested in psychological consequences of body defects which fall into two categories:

-

•

direct consequences – (effects occurring in the CNS, vegetative or neurohormonal systems) likely to be manifested by: memory, thinking or speech disorders; emotional disturbance, excessive impulsiveness, hyperexcitability (these issues are dealt with by neuropsychology and other disciplines, therefore, they will not be discussed in this article, although such dysfunctions do apply for example to patients who have their heads irradiated);

-

•

indirect consequences – occurring when an affected person starts to notice, assess and take a specific approach towards their disability, also driven by other people's reactions to the new condition.8

Disabled persons experiencing cancer and its treatment or persons who have become disabled due to oncology treatment tend to perceive their experiences as traumatic physical or psychological injuries that generate many life problems and psycho-pathological implications.8 For that reason, an oncology psychologist working with oncology patients – particularly radiation patients, for whom treatment duration is relatively long as compared to oncology surgery departments (e.g. 4–6 weeks for breast irradiation) – or follow-up patients may decide to start the process of psychological rehabilitation (e.g. to prevent abnormal cancer-induced life crises,8 help overcome the sorrow for the lost fitness, physical attractiveness or labour market value, provide support for patients experiencing personal alienation or social exclusion or struggling to accept their disability).11–14

Individual psychological therapy adjusted to the needs and expectations of each patient, and oriented to achieve a higher level of personal and social adaptation, may be delivered by in-house professionals working in cooperation with qualified interdisciplinary staff (therapeutic teams) composed of doctors, nurses, rehabilitants, physiotherapists, and social workers. An example of this approach would be a comprehensive care provided by oncology centres to women with diagnosed breast cancer, from diagnosis through treatment to follow-up.11

3.5. Selected psychotherapy methods for hospitalised and follow-up patients

Psychologists employed by oncology centres often resort to varied therapy approaches as different methods prove effective for different patient groups and different disease or treatment stages.10 Although this eclectic approach is not approved by some psychotherapists,7 what really matters is that with diverse psychologists’ preferences, the patient is offered a choice. It is important that, regardless of the type of support given, hospitalised patients should be learnt to live with the disease, while recovered patients should be shown how to use their experiences, often very painful, as a source for development rather than self-destruction. This process usually takes much time and requires many meetings. Therefore, chemotherapy and radiotherapy departments, where treatment procedures are relatively long, seem to be good places at least to start the process.10

3.6. Active symptomatic psychotherapy

Abreactive psychotherapy may prove effective in all stages of the disease and treatment. Displaying strong emotions; talking about one's suffering, anxiety and its sources, fear of surgery, irradiation, chemotherapy; giving vent to tears, objection, anger – all this tends to bring relief and appeasement, be it temporary or permanent. The very permission, encouragement to or acceptance for such behaviour, and the feeling of safety during a meeting allow the patient to start building their internal harmony, help them take up a distance towards themselves and their condition and, consequently, accept the situation they are in. This method is often applied as a preparatory measure laying grounds for further methods.

3.7. Rational psychotherapy

Rational psychotherapy, delivered individually or collectively, is a form of preparing the patient for a physically or mentally burdening experience, e.g. irradiation. It consists in clear and understandable presentation of the treatment method being used, discussion of its possible immediate and delayed side effects, forms of self-support, importance of patient's involvement in the combat against cancer through mental reinforcement and adherence to the radiotherapist's recommendations. To this end, the psychologist may use audiovisual aids (brochures, information leaflets, videos, CDs, cassettes, computers). The preparation process has to contain answers to patients’ questions and doubts, even those of minor or individual nature. A doctor, rehabilitant, nurse or dietician may also be invited to cooperate.

Another technique, combining elements of rational and humanistic psychotherapies (mainly existential) proposes free conversation or discussion with the patient about their disease and related issues (existential values distorted or revealed by the disease, individual dimension of the disease). A conversation of that type, initiated by the patient, may have a therapeutic effect, but has to be conducted by an experienced, well-prepared therapist who needs to be sure of its value as a true support for the patient in their struggle to handle the disease and treatment.10

What can be achieved owing to those methods is to re-orient the patients, turn their negative, passive and pessimistic attitude towards the disease and its treatment into the attitude of activity and mobilisation, from ‘I surrender’ to ‘I fight’. It often proves to be a turning point opening way for acceptance and adaptation to the disease as an irreversible fact.10

3.8. Relaxation

Relaxation is a recommended and commonly used method not only by clinical psychologists working with somatic patients, but also by patients themselves as it reduces tension, improves well-being, helps alleviate low-intensity pain and chemotherapy-specific averse reactions, and mitigates some post-radiation symptoms. Some of the basic closed treatment techniques include Schultz's autogenic training, progressive Jacobson relaxation and elements of yoga. Psychologists and patients themselves often combine relaxation with the visualisation technique using patients’ imagination. The choice of the type of relaxation depends on the psychologist's and the patient's skills and preferences.15 It is important that after a therapy session the patient should be able do the exercises on their own, thus gaining an effective self-support method.

Relaxation is an autonomous method, but often applied as an introductory stage to the next two methods described below.10

3.9. Behavioural method of gradual desensitisation

Certain therapies entail distressing side effects, e.g. some cancer medicines and incidental stimuli, such as syringes, iv, the colour and smell of a medicine, white apron, experiences from childhood, disease of a beloved person, associated with one's own distressing reactions continually repeated in a multi-stage treatment cause the patient to develop anticipatory reactions (such as nausea or vomiting). They may impede treatment or even render it impossible, while becoming tiring or unbearable for the patient. If those adverse symptoms cannot be allayed by conventional medicine (e.g. by antiemetics), the gradual desensitisation technique preceded by relaxation might prove helpful.10

3.10. Suggestive psychotherapy and hypnotism

Suggestive techniques, as well known, are an autonomous form of psychotherapy. They usually accompany abreaction, relaxation, forms of communication and supportive psychotherapy. Properly customised suggestive measures may be very helpful in stimulating and encouraging the patient to undergo treatment, counteract adverse influence of the hospital environment (negative states and behaviours mutually induced by patients – poor well-being, bad mood or even nausea or vomiting), they may also prove an effective weapon in the combat against pain, strengthen effects of certain medicines or even allow temporary reduction of doses.10

Hipnotherapy is used to mitigate excessive tension, anxiety, pain and depression. This method, however, requires a thorough preparation, experience, and strict compliance with relevant indications and recommendations.10

3.11. Supportive psychotherapy

Supportive psychotherapy is about giving support to the patient, encouraging them to openness in the expression of feelings, attempting to reach to their strong personality assets and revealing them, referring to the current situation, building the sense of safety and trust in oneself and the social environment. The only prerequisites for this type of therapeutic contacts are truthfulness, high frequency of meetings, desire to find a place for oneself in the reality of the disease. For that reason, supportive psychotherapy is often applied with hospitalised patients.

This method is often selected as an introduction to those described above. It may, however, serve as an independent method or in combination, for instance, with informative psychotherapy, as is often practised for elderly people with low flexibility of behaviour or patients in the advanced stages of cancer, physically disabled, or those suffering from loneliness or helplessness.10 If based on good contacts and strong emotional bond, this method fosters mental balance, facilitates adaptation to hospital conditions, may help in finding hidden resources of patience or the will to act (which is particularly vital for palliative treatment).10,16

3.12. Family psychotherapy

The term family psychotherapy does not indicate a method of action but rather its subject. A cooperation of this kind usually involves one of family members (mostly somebody significant and close to the patient). In the case of a child, both parents may be involved in the psychotherapy. Family psychotherapy usually resorts to abreactive, rational and supportive psychotherapy methods. It can be delivered individually or collectively. At meetings, family members may find out about treatment methods, side effects or possibilities of nursery assistance from the family. They can also share their views about emotional difficulties experienced by the patient and their family and the importance of being open in mutual relationships.10

The stress evoked by the disease of a beloved person is so great that elementary needs of the patient are often forgotten, there comes an overwhelming feeling of helplessness bordering on apathy, attention tends to be focused on matters that are not necessarily important. The psychotherapist can help the patient's family in displaying their emotions, learning new forms of activity meant to provide the patient with a useful and comprehensive assistance during the disease, treatment or rehabilitation, or care and support, if treatment proves inefficient.10

4. Conclusion

The above-described forms and methods of psychologists’ work with oncology patients and their families during the radiation treatment and follow-up stages are used throughout the long-lasting therapy and follow-up. The specific nature of cancer, as discussed at the beginning of this article, causes patients to be hit hard with the feeling of internal chaos and uncertainty, to lose the sense of safety and experience a crisis. They want a psychologist to help them overcome fear, reduce anxiety and find hidden resources of energy and the desire to live, ever so needed to fight with the disease. If they are satisfied with the support they have been provided, if it gives them what they have expected, they start to find patience to endure the treatment and return to a normal life. They realise that something important has happened in their lives, a change for better perhaps, a change that they will benefit from for a long time.

Conflict of interest

None declared.

Financial disclosure

None declared.

References

- 1.Bryniarska K. Luxury of suffering disease with dignity. In: Krzemionka-Brózda D., Mariańczyk K., Świeboda-Toborek L., editors. Forces that overcome cancer: belief, hope, health. Wydawnictwo Charaktery; Kielce: 2005. pp. 155–163. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Winch B. National School of Psycho-Oncology, Polish Psycho-Oncology Association; Gdańsk: 2006. Cancer progression rate and psychological support. Training trainers in Psycho-Oncology. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gregurek R., Bras M., Dordević V., Ratković A.S., Brajkovic L. Psychological problems of patients with cancer. Psychiatr Danub. 2010;22(2):227–230. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turuk-Nowakowa T. Psychologist's conduct in cancer patients. In: Heszen-Niejodek I., editor. Psychologist's role in diagnostics and treatment of somatic diseases. PZWL; Warszawa: 1990. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fiore N. Fighting cancer – one patient's perspective. N Eng J Med. 1979;300(6):284–289. doi: 10.1056/NEJM197902083000604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kalvodowá L., Vorlícek J., Adam Z., Svacina P. A psychological perspective on the problems faced by the oncology patients and their care teams. Vnitřní lékařství. 2010;56(6):570–581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Czabała C.z., Sęk H. Psychological support. In: Strelau J., editor. Psychology. Student textbook, part 3. Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne; Gdańsk: 2000. pp. 605–622. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sęk H. Introduction to clinical psychology. In: Brzeziński J., editor. Lectures in psychology, part 5. Wydawnictwo Naukowe Scholar; Warszawa: 2001. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Polish Psycho-Oncology Association [Internet]. Gdańsk: Psycho-Oncology. Available from: http://www.ptpo.org.pl/index/index.php?option=com_content&task=blogcategory&id=22&Itemid=34 [accessed 19.07.12].

- 10.Turuk-Nowak T. Psychological support to oncology patients. In: Kubacka-Jasiecka D., Łosiak W., editors. Struggling with cancer. Modern psychology approach to cancer patients. Wydawnictwo Uniwersytetu Jagiellońskiego; Kraków: 1999. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kowalik S. Psychological attitudes to disability and rehabilitation. In: Strelau J., editor. Psychology. Student textbook, part 3. Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne; Gdańsk: 2000. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Izdebski P. Wydawnictwo Akademii Bydgoskiej im. Kazimierza Wielkiego; Bydgoszcz: 2002. Psychological background of breast cancer. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Andritsch E., Goldzewig G., Samonigg H. Changes in psychological distress of women in long-term remission from brest cancer in two diffrent geographical settings: a randomized study. Support Care Cancer. 2004;12(1):10–18. doi: 10.1007/s00520-003-0531-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baider L., Andritsch E., Goldzewig G. Changes in psychological distress of women with breast cancer in long-term remission and their husbands. Psychosomatics. 2004;45(1):58–68. doi: 10.1176/appi.psy.45.1.58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stanczyk M.M. Music therapy in supportive cancer care. Rep Pract Oncol Radiother. 2011;16(5):170–172. doi: 10.1016/j.rpor.2011.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bukczyński F. National School of Psycho-Oncology, Polish Psycho-Oncology Association; Warszawa: 2006. Family coping with disease. Psychological issues in palliative/hospice care. [in Polish] [Google Scholar]