Abstract

Emerging research suggests that antisocial behavior in youth is linked to abnormal brain white matter microstructure, but the extent of such anatomical connectivity abnormalities remain largely untested because previous Conduct Disorder (CD) studies typically have selectively focused on specific frontotemporal tracts. This study aimed to replicate and extend previous frontotemporal diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) findings to determine whether noncomorbid CD adolescents have white matter microstructural abnormalities in major white matter tracts across the whole brain. Seventeen CD-diagnosed adolescents recruited from the community were compared to a group of 24 non-CD youth which did not differ in average age (12–18) or gender proportion. Tract-based spatial statistics (TBSS) fractional anisotropy (FA), axial diffusivity (AD), and radial diffusivity (RD) measurements were compared between groups using FSL nonparametric two-sample t test, clusterwise whole-brain corrected, p<.05. CD FA and AD deficits were widespread, but unrelated to gender, verbal ability, or CD age of onset. CD adolescents had significantly lower FA and AD values in frontal lobe and temporal lobe regions, including frontal lobe anterior/superior corona radiata, and inferior longitudinal and fronto-occpital fasciculi passing through the temporal lobe. The magnitude of several CD FA deficits was associated with number of CD symptoms. Because AD, but not RD, differed between study groups, abnormalities of axonal microstructure in CD rather than myelination are suggested. This study provides evidence that adolescent antisocial disorder is linked to abnormal white matter microstructure in more than just the uncinate fasciulcus as identified in previous DTI studies, or frontotemporal brain structures as suggested by functional neuroimaging studies. Instead, neurobiological risk specific to antisociality in adolescence is linked to microstructural abnormality in numerous long-range white matter connections among many diverse different brain regions.

Introduction

Conduct Disorder (CD) is defined by the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (4th Edition; DSM-IV) as characterized by a pattern of antisocial behavior before age 18, including aggression, damage of property, deceitfulness or theft, and rules violations. Because early life onset of antisocial behavior increases the risk for persistent disorder, other mental health problems, and delinquency (Moffitt et al., 2008; Moffitt et al., 2001), researchers have sought to identify neural correlates of antisocial behavior that might clarify etiological mechanisms, or represent risk for antisociality. Studies of brain structure in antisocial adults consistently have found grey matter volume deficits in orbitofrontal and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (Yang et al., 2009) and in medial and lateral temporal lobe regions (Weber et al., 2008). Studies of antisocial youth typically have confirmed adult findings with evidence for orbitofrontal, anterior cingulate, insular cortex, and bilateral temporal lobe (amygdala, hippocampus, and lateral surface) volume reductions (Passamonti et al.; Vloet et al., 2008a) (see (De Brito et al., 2009) for a contrary report). Review of functional neuroimaging CD literature has noted that many of these regions have abnormal activation in antisocial samples (Rubia, 2011), particularly medial temporal lobe (e.g., amygdala) and prefrontal regions (e.g., anterior cingulate (Passamonti et al., 2012; Weber et al., 2008; Yang & Raine, 2009) and orbitofrontal cortex (Finger et al., 2008; Rubia et al., 2009b)).

This evidence supports theories that frontotemporal brain abnormalities are associated with antisocial behavior disorders (Vloet et al., 2008b), driven in large part because frontotemporal regions have been linked to cognitive and emotional functions impaired in antisocial behavior (Blair et al., 2009). In accord with these findings, studies using diffusion tensor imaging (DTI) methods to measure white matter microstructure (Basser et al., 1996) in antisocial adults scoring high on the Psychopathy Checklist-Revised (Hare, 2003) had reduced fractional anisotropy (FA) values measuring preferential diffusivity along white matter structures in the uncinate fasciculus – a tract that connects limbic system brain regions in the temporal lobe to orbitofrontal cortex (Craig et al., 2009; Sundram et al., 2012). Attempts to replicate this in youth diagnosed with Conduct Disorder using tractography methods either have found no uncinate abnormalities (Finger et al., 2012) or increased FA (Passamonti et al., 2012; Sarkar et al., 2013), interpreted as abnormal maturation of neural pathways involved in emotion or emotional control. Recent studies of antisocial adults have found numerous other DTI-measured white matter deficits (Sundram et al., 2012). However, little is known about whether other white matter tracts are abnormal in antisocial youth. One whole brain DTI study of CD/Oppositional Defiant Disorder (ODD)-diagnosed youth high on callous/unemotional traits found no abnormalities when testing other major tracts in the brain (Finger et al., 2012), while another found only external capsule FA differed from controls after correcting for multiple comparisons (Passamonti et al., 2012).

Despite the unencouraging lack of findings from some previous CD DTI studies, it is important to note that they all examined antisocial samples highly comorbid with Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD), or that had high rates of ADHD symptoms. As we (Stevens et al., 2012) and others (Rubia et al., 2010; Rubia et al., 2009a; Rubia et al., 2009b) have previously shown, examination of noncomorid CD samples can reveal important brain structure and function distinctions between relatively “pure” samples of CD and ADHD, as statistical covariance methods cannot completely control for neurodevelopmental differences arising from distinct etiological contributions to each disorder. The present study used DTI to determine whether CD-diagnosed adolescents had clearer evidence for white matter microstructural abnormalities. Our primary hypothesis was that CD adolescents who were largely free of other psychopathology would indeed show FA deficits in the major tracts connecting frontal and temporal lobe brain regions most often implicated by functional neuroimaging studies to be abnormal in adolescent and adult antisocial samples (e.g., unicinate fasiculus). We also predicted FA abnormalities in tracts that connect frontal lobe with other brain regions (e.g., superior longitudinal fasciculi or fronto-occpital fasciculi) or temporal lobe with other regions (e.g., inferior longitudinal fasciculus). Our second aim was to determine whether or not FA-measured white matter microstructure was abnormal in other major tracts throughout the brain. Such findings would be important, as current neurobiological theories of CD do not emphasize the anatomical connectivity of other brain regions. We therefore hypothesized that CD-diagnosed adolescents would have decreased FA in other major white matter connections among posterior brain regions, subcortical structures, or the cerebellum. Finally, because recent research has suggested that other DTI diffusivity indices might capture neurobiologically-specific aspects of microstructural abnormality, we supplemented the FA analyses with analyses of axial diffusivity (AD) or radial diffusivity (RD) to aid interpretation of any study findings.

Methods and Materials

Participants

Participants were recruited as part of a National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH)-funded study of brain structure and function (K23MH070036). Participants for this CD versus non-CD study were recruited using community advertisements (controls) and letters sent to families of youth on probation in the Connecticut Court Support Services Division following adjudication (CD). Written informed assent and parental permission to participate were obtained jointly from participants and a parent/legal guardian. All consent and study procedures were approved by the Hartford Hospital Institutional Review Board.

Although CD is commonly associated with other psychiatric diagnoses when presenting clinically (Ollendick et al., 2008b), numerous studies have reported comorbidity rates of as low as 7–28% for ADHD, depression or anxiety in community-recruited CD youth (Angold et al., 1999). Therefore, our objective was to assess relatively “pure” (i.e., noncomorbid) CD youth so that any abnormal findings could be more confidently ascribed to neurobiological factors contributing to antisociality itself and not another disorder. This approach can be a significant strength when attempting to distinguish complex, multifactorial etiological influences on disorders defined by broad behavioral phenotypes. Psychiatric diagnoses for research purposes were established uniformly using the Kiddie Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (Present and Lifetime Version; K-SADS-PL) semi-structured interview, which provides reliable and valid DSM-IV diagnoses based on multiple informants (Kaufman et al., 1997) to discriminate CD from other disruptive disorders (e.g., ADHD or ODD). Interviews of each participant and a parent/guardian were conducted by experienced bachelor’s- and master’s-level research assistants supervised by a clinical psychologist experienced in supervising K-SADS-PL interviews (MCS). Information from both informants was synthesized, then discussed within weekly research group consensus meetings for final formulation once sufficient information was judged present to have diagnostic confidence. If K-SADS-PL identified other (even marginally subthreshold) diagnoses, these participants did not undergo MRI. N=17 CD adolescents without any significant psychiatric or substance disorder comorbidities provided usable DTI data. As intended, CD participants typically had no other lifetime or current diagnosable psychiatric or substance disorders. For example, nearly all CD participants reported only 0 or 1 ADHD symptoms, the disorder most frequently comorbid with CD (Ollendick et al., 2008a) (CD group mean = 1.06 of 18 ADHD symptoms). One exception was a single CD participant who met criteria for cannabis abuse. This participant was retained because studies have not confirmed an effect of even prolonged regular use on brain structure (Quickfall et al., 2006). Indeed, when the primary study analysis was re-run omitting this subject, the results did not change. Seven CD participants would have qualified for ODD diagnosis if not better accounted for by CD, as per DSM-IV guidelines. CD participants were compared to n=24 non-CD control participants without current/lifetime DSM-IV diagnoses or meaningful sub-threshold symptomatology. All participants were 12–18 years old. Final CD and non-CD study dataset sizes differed for several reasons, including study attrition over a multi-day assessment protocol, failure to provide adequate quality MRI data, or time constraints on MR assessment days. All participants were medically healthy as determined from medical questionnaire parent responses. All tested negative for recent marijuana, cocaine, and heroin use on a urine drug screen the day of MRI. All participants received identical clinical and cognitive evaluations.

Sample demographic and clinical characteristics are listed in Table 1. The groups did not significantly differ by age or gender proportion. Verbal ability was estimated using the Wide Range Achievement Test (3rd Edition) (WRAT-3) (Jastak, 1993) because numerous CD participants did not exert adequate effort on the more challenging Wechsler Intelligence Scale for Children (3rd Edition; WISC-III) or Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale (3rd Edition; WAIS-III) Vocabulary subtests originally intended to estimate verbal-conceptual ability (i.e., many refused to complete the tests or did not provide credible answers as test items became difficult). The WRAT-3 has a moderately strong correlation with IQ (Griffin et al., 2002; Strauss et al., 2006). Consistent with previous research (Moffitt, 1993b; Moffitt et al., 1994), verbal ability was significantly lower in CD relative to controls (t39=5.09, p<.001). Nonverbal intelligence (estimated by the WASI Matrix Reasoning subtest) did not differ between groups. Number of ADHD symptoms did not significantly differ between groups. Roughly half (9 of 17) of CD youth had CD onset in adolescence; the rest childhood. CD age onset classifications did not differ by gender or age.

Table 1.

Sample demographic and clinical characteristics.

| Conduct Disorder Mean (SD) |

Healthy Controls Mean (SD) |

p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 15.9 (1.0) | 15.6 (1.7) | ns |

| Gender (M/F) | 10/7 | 15/9 | ns |

| WRAT-3 Reading Scaled Score | 86.6 (9.5) | 104.2(11.8) | <0.00001 |

| Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence – Matrix Reasoning subtest T-Scorea | 47.9 (7.72) | 51.8 (6.41) | ns |

| K-SADS-PL | |||

| CD symptoms | 5.6 (2.1) | 0.0 (0) | <0.00001 |

| AD/HD Inattentive symptoms | 0.7 (1.4) | 0.05 (0.2) | <0.05 |

| AD/HD Hyperactivity/Impulsivity symptoms | 0.4 (0.9) | 0.1 (0.4) | ns |

| CD Age of Onset | |||

| Childhood | 47% | ||

| Adolescent | 53% | ||

WASI MR data was not collected for 3 CD and 5 non-CD participants.

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) Data Collection and Data Preparation

MRI data were obtained on a Siemens 3T Allegra MRI machine located at the Olin Neuropsychiatry Research Center at The Institute of Living/Hartford Hospital. The pulse sequence was single-shot spin echo planar imaging sequence, repetition time (TR)/echo time (TE)=6300/82 ms, field of view (FOV)=200 mm, matrix = 128×128, 8 averages, diffusion sensitizing orientations=12 with b=1000 s/mm2, and one with b=0 s/mm2, 45 contiguous axial slices with 1.6×1.6×3.0 mm resolution. To minimize blood flow and cerebrospinal fluid pulsation effects, scanning was gated with peripheral arterial pulse. Total scan time 11:02 min. Participants also underwent several other research scans as part of a larger NIMH-funded project that will be described in other reports.

MRI DTI images were prepared for analysis using several steps within the FMRIB Software Library v5.0 (FSL) (Jenkinson et al., 2012). An initial data quality check ensured that gradient direction measurements with excessive motion artifacts or noise were identified and removed. Next, motion and eddy current correction was done by registering diffusion weighted images to a common non-diffusion weighted image by FLIRT/FSL with a mutual information cost function. We then calculated diffusion tensor and scalar FA measures for voxels within a mask created from the B0 image. These data were spatially normalized to a common Montreal Neurological Institute (MNI) space template using FNIRT/FSL. For TBSS, we calculated a subject specific mean FA image from the 41 participants, then applied tract based spatial statistics (TBSS/FSL) method (Smith et al., 2006) to calculate subject specific skeletons. The TBSS algorithm searches for the maximum FA in the direction perpendicular to the skeleton within a limited range and projects it onto the skeleton. Thus, we created subject-specific FA values defined on one common skeleton for the whole group. These skeletonized FA images were used in subsequent random effects analyses to test study hypotheses. Subject-specific RD and AD skeleton images also were created by this approach and used for supplemental random effects analyses, intended to clarify the likely nature of any CD abnormalities detected by FA. AD and RD indices are believed to capture different aspects of white matter microstructure abnormality. For instance, Song and colleagues (Song et al., 2003; Song et al., 2002; Song et al., 2005) have presented a model in which the primary DTI eigenvalue (‘axial diffusion’) and the average of the secondary and tertiary eigenvalues (‘radial diffusion’) are thought to be differentially sensitive to axonal integrity and myelination, respectively.

Hypothesis Testing and Supplemental Analyses

Study hypotheses were tested using two-sample t test on participants’ individual FA skeleton images using FSL’s ‘randomise’ program (Jenkinson et al., 2012). Relevant t contrasts were Controls > CD and Controls < CD. Statistical significance was evaluated using non-parametric, permutation-based (5000 permutations) threshold-free cluster enhancement (TFCE) (Smith et al., 2009), using options that optimally evaluated the 2D connectivity structure found in skeletonized images. Primary group contrast results are presented if they survived corrections for searching the entire skeleton, p<.05 TFCE. Findings were illustrated using relevant 3 mm axial slices after “thickening” the comparison results for display purposes by smoothing the statistical image and multiplying by the mean FA image to constrain the width of the enlarged clusters. The FA study group comparison was supplemented by FSL t tests on AD and RD skeleton images, using identical models and significance thresholds as in the primary analysis. We also computed Cohen’s d effect sizes (Cohen, 1988) based upon the uncorrected peak t statistic for reported clusters ( ) for all significant findings to help differentiate weaker findings from more robust effects that might best guide future research effort. An exploratory FSL regression examined regions of CD FA deficits to see if any were significantly associated with CD severity (i.e., sum of threshold DSM-IV symptoms). Because this question entailed examination of only brain regions where there were CD abnormalities, we masked the results of this correlation with results from the primary study group comparison. Clusterwise statistical corrections were less relevant when using an arbitrarily constrained search space, so we report any areas of association between CD severity and FA values that reached p < .05 uncorrected, >20 contiguous voxels.

Finally, verbal abilities, gender, and CD age of onset deserve careful consideration in any comparison of CD and non-CD adolescents, as they possibly reflect etiologically important influences on brain structure/function. Verbal intelligence and executive abilities are often lower in DSM-IV CD (Moffitt, 1993b; Moffitt & Lynam, 1994). Gender and age of CD onset also may play a role in CD etiology given the greater 4:3 CD male gender ratio (Merikangas et al., 2010) and the proposal that early onset CD could involve a greater neurobiological loading (Moffitt, 1993a; Moffitt et al., 2008). In case-control designs where random assignment to experimental condition is not possible to control for factors such as gender or age of onset, ANCOVA is well argued to be inappropriate (Miller et al., 2001) as it can obscure true relationships among etiological influences. We therefore examined gender, CD age of onset and the linear relationship of WRAT-3 Reading score with FA within CD participants post hoc in voxelwise analyses to determine if these factors might modify our understanding of any identified CD vs non-CD FA differences. Because we were interested in possible effects of these factors across brain, these post hoc analyses used TFCE-clusterwise p<.05 thresholds corrected for searching the entire FA skeleton, with uncorrected effects noted if theoretically relevant.

Results

FSL analyses on the skeletonized FA maps found numerous brain regions where FA was significantly reduced in CD-diagnosed adolescents compared to controls. The results are presented in Tables 2 and 3 as anatomically distinct loci at least > 5 mm apart), and depicted in Figure 1. Table 2 presents major tracts that could be localized with reasonable certainty through comparison to visual and electronic atlases (Hua et al., 2008; Mori et al., 2005), including region labels, peak t scores from group comparison, TFCE-clusterwise significance level, and Cohen’s d effect sizes. Where relevant, the labels list which lobe the effects were found within (an absence of location tag indicates sub-lobar deep white matter). Table 3 presents the same information for CD FA deficits located in subgyral white matter regions or within subcortical structures.

Table 2.

Significant clusters of voxels proximal to major white matter tracts along the TBSS-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) and axial diffusivity (AD) skeletons where Conduct Disorder < Healthy Control participants. Results depict peak x,y,z coordinates, peak t scores, threshold-free cluster-enhancement corrections for searching the entire skeleton (p < .05 or better), and Cohen’s effect size for each regional finding. Note, there were no group differences for radial diffusivity (RD).

| White matter label | Fractional Anisotropy (FA) | Axial Diffusivity (AD) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| Peak x,y,z | Peak t | TFCE-corrected cluster p | Cohen’s d | Peak x,y,z | Peak t | TFCE-corrected cluster p | Cohen’s d | |

| Left superior corona radiata | −29,−5,19 | 4.63 | 0.024 | 1.46 | 29,−4,21 | 3.01 | 0.004 | 0.95 |

| −29,−16,20 | 2.89 | 0.031 | 0.91 | 29,−17,18 | 1.09 | 0.016 | 0.34 | |

| Right superior corona radiata | 25,−2,20 | 2.72 | 0.031 | 0.86 | 25,−3,21 | 3.05 | 0.004 | 0.96 |

| Left anterior corona radiata (frontal) | −28,36,−1 | 2.83 | 0.046 | 0.89 | −28,36,−1 | 2.09 | 0.006 | 0.66 |

| Left anterior corona radiata | −28,19,19 | 2.41 | 0.040 | 0.76 | − | - | - | - |

| −21,30,−6 | 2.31 | 0.033 | 0.73 | −23,31,−4 | 1.93 | 0.004 | 0.61 | |

| −20,21,−11 | 3.03 | 0.032 | 0.96 | −22,22,−11 | 2.52 | 0.005 | 0.80 | |

| Right anterior corona radiata (frontal) | 26,17,20 | 3.00 | 0.029 | 0.95 | 27,17,22 | 1.71 | 0.005 | 0.54 |

| 27,22,18 | 2.26 | 0.033 | 0.71 | 27,21,18 | 2.75 | 0.004 | 0.87 | |

| 17,32,−11 | 2.88 | 0.038 | 0.91 | 17,33,−10 | 3.18 | 0.006 | 1.01 | |

| Right anterior corona radiata | 26,18,15 | 3.08 | 0.029 | 0.97 | 24,18,16 | 4.19 | 0.004 | 1.32 |

| Right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (frontal) | 24,35,3 | 2.52 | 0.039 | 0.80 | 26,35,1 | 2.36 | 0.006 | 0.75 |

| Right superior longitudinal fasciculus (frontal) | 32,8,17 | 2.27 | 0.034 | 0.72 | 32,10,16 | 3.53 | 0.011 | 1.12 |

| Right superior longitudinal fasciculus | 32,−2,19 | 3.26 | 0.028 | 1.03 | 33,−2,19 | 1.67 | 0.007 | 0.53 |

| Left superior longitudinal fasciculus (parietal) | −31,−35,39 | 2.11 | 0.043 | 0.67 | −30,−36,39 | 2.28 | 0.005 | 0.72 |

| −44,−39,34 | 2.97 | 0.047 | 0.94 | −44,−40,33 | 2.72 | 0.004 | 0.86 | |

| −47,−22,29 | 3.43 | 0.043 | 1.08 | −46,−23,29 | 3.48 | 0.005 | 1.10 | |

| −35,−28,28 | 2.39 | 0.042 | 0.76 | −35,−28,27 | 3.22 | 0.005 | 1.02 | |

| −35,−48,28 | 3.20 | 0.036 | 1.01 | −35,−47,30 | 3.61 | 0.003 | 1.14 | |

| Left inferior/superior longitudinal fasiculus (temporal) | −36,−50,10 | 3.20 | 0.037 | 1.01 | −36,−50,11 | 3.33 | 0.003 | 1.05 |

| Left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (temporal) | −36,−53,−4 | 2.93 | 0.037 | 0.93 | −37,−53,−3 | 3.21 | 0.003 | 1.02 |

| −35,−32,6 | 2.91 | 0.033 | 0.92 | −34,−32,7 | 2.03 | 0.004 | 0.64 | |

| Left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus | −33,−23,−3 | 3.50 | 0.033 | 1.11 | −34,−23,−3 | 3.23 | 0.003 | 1.02 |

| Left saggital stratum (inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus) | −37,−19,−8 | 3.10 | 0.033 | 0.98 | −37,−19,−8 | 2.07 | 0.004 | 0.65 |

| Right saggital stratum (inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus) | 35,−54,−2 | 4.97 | 0.013 | 1.57 | - | - | - | - |

| Left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus | −33,−6,−9 | 2.96 | 0.036 | 0.94 | −33,−7,−8 | 2.41 | 0.004 | 0.76 |

| Right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus | 35,−11,−7 | 4.69 | 0.020 | 1.48 | 35,−11,−6 | 4.24 | 0.007 | 1.34 |

| Right inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (temporal) | 41,−30,−7 | 2.86 | 0.026 | 0.90 | 41,−31,−7 | 1.49 | 0.010 | 0.47 |

| Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (temporal) | −46,−34,−9 | 3.88 | 0.014 | 1.23 | −47,−34,−11 | 3.17 | 0.004 | 1.00 |

| −47,−29,−13 | 2.89 | 0.014 | 0.91 | −47,−31,−13 | 2.87 | 0.004 | 0.91 | |

| −49,−24,−18 | 2.75 | 0.015 | 0.87 | −49,−23,−19 | 1.82 | 0.008 | 0.58 | |

| Right saggital stratum (inferior fronto-occipital/inferior longitudinal fasciculi) | 38,−49,−4 | 6.21 | 0.013 | 1.96 | - | - | - | - |

| Right inferior longitudinal fasciculus (temporal) | 35,−68,−6 | 3.91 | 0.024 | 1.24 | - | - | - | - |

| Right inferior longitudinal fasciculus | 42,−21,−6 | 2.77 | 0.026 | 0.88 | 42,−21,−6 | 2.85 | 0.009 | 0.90 |

| Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (occipital) | −33,−68,−4 | 3.29 | 0.037 | 1.04 | −33,−67,−4 | 3.18 | 0.003 | 1.01 |

| Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (temporal) | −33,−62,−10 | 2.50 | 0.038 | 0.79 | −34,−62,−9 | 1.68 | 0.004 | 0.53 |

| Left anterior limb of internal capsule | −21,7,20 | 2.83 | 0.035 | 0.89 | −21,8,22 | 2.63 | 0.005 | 0.83 |

| −15,8,6 | 2.75 | 0.034 | 0.87 | −15,8,7 | 3.21 | 0.003 | 1.02 | |

| −13,6,5 | 2.84 | 0.035 | 0.90 | −13,7,4 | 2.28 | 0.004 | 0.72 | |

| Right anterior limb of internal capsule | 23,6,17 | 3.35 | 0.029 | 1.06 | 23,5,18 | 5.12 | 0.004 | 1.62 |

| 14,8,6 | 2.97 | 0.036 | 0.94 | 15,9,6 | 3.26 | 0.004 | 1.03 | |

| 12,9,1 | 2.62 | 0.036 | 0.83 | 12,10,2 | 1.85 | 0.005 | 0.59 | |

| Midbrain | 1,−18,−8 | 3.14 | 0.008 | 0.99 | 2,−19,−6 | 1.95 | 0.006 | 0.62 |

| −2,−30,−14 | 3.50 | 0.007 | 1.11 | - | - | - | - | |

| Left superior cerebellar peduncle | −5,−31,−18 | 3.82 | 0.007 | 1.21 | −5,−30,−19 | 3.43 | 0.005 | 1.08 |

| −6,−41,−25 | 4.40 | 0.011 | 1.39 | −6,−44,−26 | 3.59 | 0.008 | 1.14 | |

| Right superior cerebellar peduncle | 6,−31,−20 | 4.89 | 0.006 | 1.55 | 6,−31,−19 | 4.04 | 0.022 | 1.28 |

| 7,−40,−26 | 3.78 | 0.008 | 1.20 | 7,−38,−23 | 5.48 | 0.019 | 1.73 | |

| Left middle cerebellar peduncle | −17,−50,−29 | 3.49 | 0.010 | 1.10 | - | - | - | - |

| −20,−53,−31 | 4.20 | 0.010 | 1.33 | - | - | - | - | |

| −30,−54,−42 | 3.36 | 0.013 | 1.06 | - | - | - | - | |

| Right middle cerebellar peduncle | 17,−48,−31 | 2.98 | 0.013 | 0.94 | 17,−48,−31 | 3.5 | 0.005 | 1.11 |

| 20,−52,−31 | 2.57 | 0.013 | 0.81 | 20,−52,−31 | 2.41 | 0.049 | 0.76 | |

Table 3.

Significant clusters of voxels within gyral or subcortical white matter on the TBSS-derived fractional anisotropy (FA) or axial diffusivity (AD) skeletons where Conduct Disorder < Healthy Control participants. Results depict peak x,y,z coordinates, peak t scores, threshold-free cluster-enhancement corrections for searching the entire skeleton (p < .05 or better), and Cohen’s effect size for each regional finding.

| Fractional Anisotropy (FA) | Axial Diffusivity (AD) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

| ||||||||

| White matter label | Peak x,y,z | Peak t | TFCE-corrected cluster p | Cohen’s d | Peak x,y,z | Peak t | TFCE-corrected cluster p | Cohen’s d |

| Right middle frontal gyrus | 29,16,39 | 3.41 | 0.046 | 1.08 | 29,17,39 | 3.59 | 0.004 | 1.14 |

| 31,6,41 | 2.69 | 0.046 | 0.85 | 31,8,42 | 2.69 | 0.023 | 0.85 | |

| Left cerebral white matter | −18,8,40 | 4.11 | 0.049 | 1.30 | −18,8,40 | 1.78 | 0.049 | 0.56 |

| Left inferior frontal gyrus/frontal pole | −36,39,11 | 3.47 | 0.046 | 1.10 | −33,43,11 | 1.90 | 0.006 | 0.60 |

| Left inferior frontal gyrus | −38,24,16 | 2.47 | 0.047 | 0.78 | - | - | - | - |

| −33,19,21 | 1.98 | 0.047 | 0.63 | - | - | - | - | |

| Left subcallosal cortex/ventromedial prefrontal | −15,20,−22 | 2.46 | 0.046 | 0.78 | - | - | - | - |

| Left frontal orbital | −14,23,−22 | 2.92 | 0.046 | 0.92 | - | - | - | - |

| Left gyrus rectus | −4,31,−23 | 2.47 | 0.042 | 0.78 | - | - | - | - |

| Left orbitofrontal cortex | −35,31,−6 | 2.09 | 0.047 | 0.66 | - | - | - | - |

| Right parietal white matter | 22,−61,36 | 2.89 | 0.036 | 0.91 | 22,−60,35 | 2.01 | 0.014 | 0.64 |

| 33,−62,24 | 2.99 | 0.036 | 0.95 | - | - | - | - | |

| Left precuneus | −15,−57,30 | 2.50 | 0.044 | 0.79 | −15,−57,30 | 2.59 | 0.008 | 0.82 |

| −4,−64,20 | 3.41 | 0.045 | 1.08 | - | - | - | - | |

| Left middle temporal gyrus | −56,−32,−10 | 2.58 | 0.046 | 0.82 | - | - | - | - |

| Right middle temporal gyrus | 53,−46,0 | 3.93 | 0.033 | 1.24 | - | - | - | - |

| Left inferior temporal gyrus | −49,−26,−24 | 2.90 | 0.015 | 0.92 | −50,−26,−25 | 2.21 | 0.009 | 0.70 |

| −49,−38,−22 | 2.94 | 0.013 | 0.93 | −50,−38,−21 | 1.67 | 0.009 | 0.53 | |

| −44,−31,−27 | 2.67 | 0.017 | 0.84 | −44,−31,−28 | 2.94 | 0.009 | 0.93 | |

| Right inferior temporal gyrus | 52,−38,−19 | 4.06 | 0.045 | 1.28 | - | - | - | - |

| 53,−47,−21 | 4.29 | 0.046 | 1.36 | - | - | - | - | |

| Left fusiform gyrus | −37,−15,−25 | 4.00 | 0.045 | 1.26 | - | - | - | - |

| Left lateral occipital cortex | −37,−80,3 | 2.68 | 0.046 | 0.85 | −36,−80,3 | 3.26 | 0.002 | 1.03 |

| Right Heschel’s Gyrus | 51,−18,2 | 3.04 | 0.046 | 0.96 | 50,−20,3 | 2.58 | 0.023 | 0.82 |

| Right temporal-occipital fusiform gyrus | 41,−49,−17 | 2.45 | 0.038 | 0.77 | - | - | - | - |

| Left thalamus | −3,−6,2 | 2.93 | 0.009 | 0.93 | −3,−7,1 | 1.58 | 0.012 | 0.50 |

| −6,−16,1 | 4.31 | 0.008 | 1.36 | - | - | |||

| Right thalamus | 4,−8,2 | 2.93 | 0.009 | 0.93 | 4,−6,−1 | 2.59 | 0.006 | 0.82 |

| 8,−14,2 | 3.92 | 0.008 | 1.24 | 8,−13,3 | 2.80 | 0.005 | 0.89 | |

| Right pallidum | 16,−3,−10 | 2.75 | 0.039 | 0.87 | - | - | - | - |

| Left pallidum | −18,−5,−10 | 3.63 | 0.033 | 1.15 | - | - | - | - |

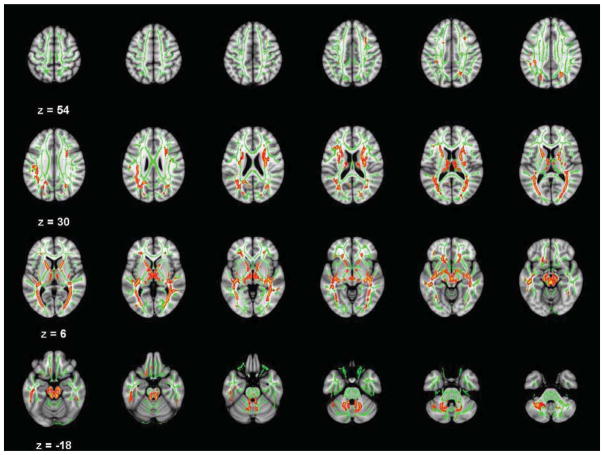

Figure 1.

Axial slices (3 mm) of significant Conduct Disorder fractional anisotropy (FA) deficits relative to controls (TFCE-clusterwise p<.05 corrected for searching the entire white matter skeleton). Significance level of the finding is indicated by red-yellow color scheme. All findings are overlaid on a green outline of the TBSS-generated tract skeleton.

Several major tracts connecting frontal lobe to other brain regions had significantly reduced FA in CD relative to controls. These included fibers within the anterior and superior corona radiata bilaterally, bilateral fronto-occipital fasciculi in both frontal and temporal lobe areas, bilateral superior longitudinal fasciculi in the parietal lobe and the left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (primarily in temporal and occipital regions). Significant CD FA reductions also were noted in the bilateral anterior limbs of the internal capsule, bilateral midbrain, bilateral posterior thalamic radiation/sagittal strata, and bilateral superior and middle cerebellar peduncles. The corpus callosum had FA deficits in CD in the genu, but these did not survive clusterwise corrections for multiple comparisons. There were no significant findings of greater FA in CD relative to controls.

Supplemental analyses found no evidence for adolescent CD abnormalities in RD. However, there were widespread abnormalities in AD. Because there was substantial overlap with the FA findings, peak t scores from group comparison, TFCE-clusterwise significance level, and Cohen’s d effect sizes for AD analyses are also presented in Tables 2 and 3. Nearly all the FA abnormalities that were localized to major labeled tracts also had overlapping or highly proximal CD AD deficits. However, only about half of the subgyral white matter regions identified in the FA analysis also showed evidence for lower AD. Specifically, there was no corresponding evidence for lower CD AD in several areas where CD FA deficits were found, including left inferior frontal gyrus, ventromedial prefrontal cortex white matter, bilateral middle temporal gyrus, right inferior temporal gyrus, or pallidum.

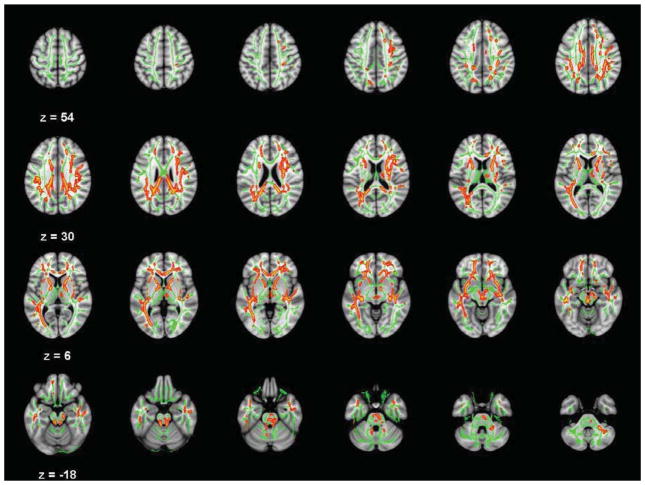

Table 4 lists numerous additional brain regions where lower AD was found in CD in regions that did not co-localize with FA deficits. AD analysis identified CD abnormalities in bilateral uncinate, bilateral cingulum, bilateral forceps minor, bilateral inferior longitudinal fasciculus, the genu, body, and splenium of the corpus callosum in both hemispheres, right superior longitudinal fasciculus, right white matter in posterior corona radiata, several subgyral white matter regions in middle frontal and middle temporal gyri, and some clusters in the right cerebellum and brainstem. The AD study group comparisons results are depicted in Figure 2.

Table 4.

Significant clusters of voxels proximal to major white matter tracts along the TBSS-derived axial diffusivity (AD) skeleton or in subgyral white matter where Conduct Disorder < Healthy Control participants in regions that did not overlap with FA abnormalities. Results depict peak x,y,z coordinates, peak t scores, threshold-free cluster-enhancement corrections for searching the entire skeleton (p < .05 or better), and Cohen’s effect size for each regional finding.

| Description | Peak x,y,z | Peak t | TFCE-corrected cluster p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Left uncinate fasciculus | −16,47,−8 | 4.59 | 0.043 | 1.45 |

| −28,9,−10 | 3.68 | 0.004 | 1.16 | |

| Right uncinate fasciculus | 15,47,−12 | 2.16 | 0.009 | 0.68 |

| 29,10,−10 | 3.38 | 0.008 | 1.07 | |

| Left corpus callosum genu | −7,31,3 | 1.55 | 0.006 | 0.49 |

| Right corpus callosum genu | 9,31,3 | 3.93 | 0.004 | 1.24 |

| 11,31,10 | 2.99 | 0.004 | 0.95 | |

| Left corpus callosum body | −9,−19,32 | 1.84 | 0.005 | 0.58 |

| −12,−29,28 | 3.34 | 0.004 | 1.06 | |

| Right corpus callosum body | 10,−5,33 | 2.06 | 0.012 | 0.65 |

| 13,−29,28 | 3.18 | 0.011 | 1.01 | |

| Left corpus callosum splenium | −15,−45,18 | 1.59 | 0.005 | 0.50 |

| Right corpus callosum splenium | 15,−43,19 | 2.42 | 0.011 | 0.77 |

| Right cingulum | 20,15,42 | 2.83 | 0.032 | 0.89 |

| 13,45,34 | 2.15 | 0.033 | 0.68 | |

| Left cingulum | −6,−8,36 | 1.20 | 0.009 | 0.38 |

| Right forceps minor | 19,44,19 | 2.76 | 0.031 | 0.87 |

| Left forceps minor | −18,42,20 | 2.45 | 0.012 | 0.77 |

| Right superior longitudinal fasciculus | 36,11,19 | 2.90 | 0.005 | 0.92 |

| 39,−15,30 | 2.43 | 0.007 | 0.77 | |

| 44,−40,30 | 2.50 | 0.013 | 0.79 | |

| 33,−24,26 | 2.23 | 0.007 | 0.71 | |

| 38,−34,30 | 1.81 | 0.012 | 0.57 | |

| Right inferior longitudinal fasciculus | 42,1,−24 | 2.87 | 0.010 | 0.91 |

| Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus | −41,0,−25 | 2.40 | 0.048 | 0.76 |

| Right posterior corona radiata | 25,−34,28 | 2.83 | 0.011 | 0.89 |

| Left middle frontal gyrus | −24,48,−6 | 1.50 | 0.008 | 0.47 |

| Right middle frontal gyrus | 25,46,−6 | 3.54 | 0.006 | 1.12 |

| 36,34,−4 | 2.27 | 0.006 | 0.72 | |

| Right middle temporal gyrus (posterior) | 58,−22,−16 | 1.65 | 0.012 | 0.52 |

| 53,−11,−21 | 3.00 | 0.009 | 0.95 | |

| Right pontine crossing tract | 6,−31,−41 | 1.62 | 0.009 | 0.51 |

| 4,−30,−29 | 1.67 | 0.023 | 0.53 | |

| Right corticospinal tract | 10,−25,−30 | 1.76 | 0.009 | 0.56 |

| Right middle cerebellar peduncle | 3,−18,−30 | 2.33 | 0.008 | 0.74 |

| Right cerebellum crus II | 35,−48,−42 | 2.40 | 0.049 | 0.76 |

Figure 2.

Axial slices (3 mm) of significant Conduct Disorder axial diffusivity (AD) deficits relative to controls (TFCE-clusterwise p<.05 corrected for searching the entire white matter skeleton). Significance level of the finding is indicated by red-yellow color scheme. All findings are overlaid on a green outline of the TBSS-generated tract skeleton.

Preliminary evidence for associations between high CD severity and lower FA was found in several white matter regions listed in Table 5. The strongest effect was found for the sagittal stratum in the right hemisphere. In addition, lower FA in small regions of anterior, superior and posterior corona radiata, left hemisphere tracts between the frontal and posterior brain regions, and several subgyral white matter regions in the frontal and parietal lobes also were linked to a greater DSM IV CD symptom count. Only two regions in the thalamus were found at these exploratory thresholds where greater CD symptoms correlated with higher FA values.

Table 5.

Brain regions within CD > Control fractional anisotropy (FA) effects where CD DSM IV symptom counts had a significant relationship with less FA in the CD study group. Results depict peak x,y,z coordinates, peak t scores, uncorrected significance levels, and Cohen’s effect size for each regional finding.

| White matter label | Peak x,y,z | # voxels | Peak t | Uncorrected p | Cohen’s d |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative FA correlation with CD severity | |||||

| Right anterior corona radiata | 27,17,10 | 33 | 3.70 | 0.0012 | 1.91 |

| 25,12,20 | 55 | 2.90 | 0.0052 | 1.50 | |

| Left superior corona radiata | −18,10,41 | 22 | 2.42 | 0.0116 | 1.25 |

| Right superior corona radiata | 28,−2,21 | 45 | 3.06 | 0.0028 | 1.58 |

| Right orbitofrontal cortex | −34,31,−6 | 35 | 4.86 | 0.0002 | 2.51 |

| Right saggital stratum (inferior fronto-occipital/inferior longitudinal fasciculi) | 34,−60,7 | 412 | 4.45 | 0.0002 | 2.30 |

| 37,−39,6 | 23 | 2.63 | 0.0094 | 1.36 | |

| 41,−40,−4 | 56 | 2.86 | 0.0064 | 1.48 | |

| Left fusiform gyrus | −38,−13,−25 | 21 | 2.95 | 0.003 | 1.52 |

| Left inferior fronto-occipital fasciculus (temporal) | −33,−30,3 | 62 | 3.23 | 0.0042 | 1.67 |

| Left inferior longitudinal fasciculus (temporal) | −42,−22,−16 | 42 | 3.86 | 0.0004 | 1.99 |

| −32,−57,−12 | 25 | 2.68 | 0.0064 | 1.38 | |

| Left corpus callosum splenium | −18,−51,24 | 33 | 3.00 | 0.0036 | 1.55 |

| Left lateral occipital/precuneus | −21,−77,34 | 26 | 3.64 | 0.0022 | 1.88 |

| Left precuneus | −8,−56,15 | 23 | 2.90 | 0.0074 | 1.50 |

| Right precuneus | 22,−65,34 | 30 | 3.18 | 0.0026 | 1.64 |

| Left posterior corona radiata | −32,−50,23 | 25 | 3.54 | 0.0026 | 1.83 |

| Positive FA correlation with CD severity | |||||

| Right anterior thalamic radiation (thalamus) | 8,−4,11 | 26 | 3.65 | 0.0016 | 1.88 |

| Left anterior thalamic radiation (thalamus) | −7,−6,12 | 25 | 3.54 | 0.0002 | 2.30 |

No white matter regions in CD were significantly associated with WRAT-3 Reading subtest score, nor were gender FA differences observed in the CD group at either corrected or non-corrected p<.05 TFCE thresholds. At corrected significance levels, there were no FA differences between early- and adolescent-onset CD youth. At exploratory uncorrected levels, two areas of reduced FA in early-onset CD were found within bilateral medial temporal lobe (x,y,z=−15,−6,−24, t16=2.83, p<.002 and x,y,z=16,−4,−23, t16=2.97, p<.018) and in left gyrus rectus white matter (x,y,z=7,19,−19, t16=2.78, p<.033). CD adolescent-onset youth had FA deficits relative to early-onset in left forceps minor (x,y,z=−14,40,−13, t16=1.84, p<.042) left internal capsule (x,y,z=−19,0,12, t16=2.60, p<.038) and left superior corona radiata (x,y,z=−21,3,24, t16=3.10, p<.031).

Discussion

The major finding of this study was that CD adolescents had decreased FA and AD in numerous major white matter tracts, implicating a greater number of neural systems than suggested by previous DTI studies of antisocial youth. As expected, there were abnormalities within tracts connecting frontal and temporal lobes to other brain regions – regions already known through functional neuroimaging or grey matter volumetric studies to be abnormal in antisocial disorders (Gao et al., 2009; Glenn et al., 2008; Moffitt et al., 2008; Rubia, 2010; Vloet et al., 2008a; Weber et al., 2008) and linked to emotion and social deficits. A recent study showed a relationship between right inferior longitudinal fasciculus association fiber FA (bidirectional temporal and occipital lobe connections) and the ability to recognize negative emotions like fear, anger, and sadness in brain-lesioned patients (Philippi et al., 2009), supporting a possible role for these CD deficits in guiding behavior using emotional cues. We also found evidence for CD FA and AD deficits in other long association fibers – the superior (frontal and parietal lobe connections), fronto-occipital fasiculi (lateral prefrontal and parietal-occipital connections), and two dense white matter bundles interconnecting numerous cortical regions through thalamic networks. The latter included bilateral anterior limbs of the internal capsule, known to have numerous cortical projections (including those from frontal and temporal cortex) to the thalamus, and then ultimately to the brainstem (Mori et al., 2005; Schmahmann et al., 2006). Some of these CD deficits previously have been linked to social information processing impairments. A study of youth at high risk for psychotic illness found FA deficits in superior longitudinal fasciculi (Karlsgodt et al., 2009), which along with lower FA in inferior longitudinal fasciuli predicted deterioration of social functioning throughout longitudinal follow-up. Another study linked “mentalizing” task performance (i.e., the ability to consciously recognize others’ motivations) to FA measured within deep brain white matter regions-of-interest (Charlton et al., 2009). This relationship was statistically mediated by verbal intelligence and executive ability, which ultimately might help explain the relationship of often-reported CD verbal deficits (Moffitt, 1993b; Moffitt & Lynam, 1994) with brain structural abnormalities. CD FA and AD deficits also were found in the sagittal stratum, another major cortico-subcortical bundle of tracts from parietal, occipital, cingulate, and temporal regions to the thalamus and brainstem, and back to cortex from the thalamus (Schmahmann & Pandya, 2006). There also was ample evidence for FA (and to a lesser extent AD) deficits in frontal and temporal lobe subgyral white matter (possibly implicating short association fibers), as well as CD deficits in the brainstem, including the superior cerebellar peduncles. The latter form the major connections from cerebellar dentate nucleus to the thalamus, and the middle cerebellar peduncles that interconnect cerebellum and pons. Finally, bilateral midbrain CD FA and AD deficits also were found, implicating one or more of several tracts connecting cortex and spinal cord. Many of the CD deficits found correspond to abnormalities found in antisocial adults (Sundram et al., 2012), but the TBSS methods used in this study provide greater specificity of findings to specific tracts than the large clusters detected in that study.

The dispersion of abnormalities across many brain regions in CD raises the interesting possibility that a generalized vulnerability to optimal white matter development might be present in CD – either a biological factor that might be tracked back to genetically-influenced mechanisms that directly compromise neuronal structure or function, or perhaps differences that confer heightened susceptibility to detrimental environmental effects on cellular growth and organization. Because FA differences could represent myelination, axon density, axon diameter, membrane permeability, or even axonal orientation (Jones et al., 2013), simple DTI tensor calculations as employed here cannot conclusively link the regional abnormalities found in this study to any specific mechanism. However, models derived from animal research have shown that RD increases can reflect demyelination, while lower AD implicates abnormalities of the axon structure itself (Song et al., 2003; Song et al., 2002; Song et al., 2005). In our study, the absence of any RD abnormalities in CD, coupled with relatively lower AD in regions that closely corresponded to CD FA deficits point away from myelination interpretations and towards widespread abnormalities of axonal soma. Therefore, more recently developed MR techniques like magnetization transfer ratio (MTR) and diffusion tensor spectroscopy (DTS) (Du et al., 2013), or even ultrastructural white matter analysis of post mortem tissue, would likely be profitable to better characterize the exact nature of the DTI-measured deficits detected here.

Moreover, these extensive abnormalities suggest white matter pathophysiology in CD could affect numerous types of information processing beyond just social and emotional function. For instance, there is evidence linking greater FA in left superior longitudinal fasciculi, and bilateral forceps minor in anterior brain to lower “switch costs” (i.e., slower performance) on a task switching paradigm (Gold et al., 2010). Such performance would be expected in psychopathy, which is theorized to involve problems with response reversal linked to ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and other brain regions (Mitchell et al., 2002). In another study, FA measurements in right fronto-occipital fasciculi were related to right inferior frontal cortex activation during response inhibition (Forstmann et al., 2008). FMRI studies focusing on noncomorbid CD youth also have reported reduced activation in bilateral temporal-parietal regions during a visual Stop-Signal task (Rubia et al., 2008), insular, anterior cingulate, cerebellum, and hippocampus deficits during sustained attention, right orbitofrontal deficits during reward processing (Rubia et al., 2009b), and reduced lateral superior temporal lobe, precuneus, and right medial prefrontal cortex during interference inhibition (Rubia et al., 2009a). CD FA and AD deficits were found in many major white matter pathways connecting these brain regions and short associational fibers within gyral white matter thought to facilitate local processing in regions engaged for these forms of cognition. For example, CD cerebellar functional abnormalities (Rubia et al., 2009b) might be (perhaps causally) related to bilateral superior and middle cerebellar peduncle FA and AD abnormalities detected in this study.

Unlike studies employing tractographic methods (Passamonti et al., 2012; Sarkar et al., 2013), there was no evidence that the direct uncinate fasciculi tracts between amygdala and frontal lobe brain regions had increased FA in CD relative to controls. Nor did we find greater external capsule FA as in one study (Passamonti et al., 2012). However, our AD analyses found significant, large effect size CD deficits in bilateral unicinate, consistent with DTI findings in antisocial adults (Craig et al., 2009; Sundram et al., 2012). We also found CD AD deficits in several other tracts that were not detected by FA, including other tracts connecting the frontal and temporal lobes with other brain structures (e.g., bilateral cingulum, bilateral forceps minor, bilateral inferior longitudinal fasciculus, right superior longitudinal fasciculus, and several subgyral white matter regions in middle frontal and middle temporal gyri), as well as clusters along entire extent of the corpus callosum in both hemispheres. It is interesting that AD rather than FA identified a greater number of CD abnormalities. This indicates that AD measurements thought to be most sensitive to axonal structural integrity seem to be preferentially sensitive to CD microstructural abnormalities instead of FA measurements of overall anisotropy, despite the popularity of the latter. The uncinate and external capsule results from this study stand in contrast to previous reports describing antisocial youth (Passamonti et al., 2012; Sarkar et al., 2013). Methodological differences (TBSS vs tractrography and FA vs AD) represent possible explanations for the differences. However, because another study using similar TBSS methods found no CD FA abnormalities in any tract (Finger et al., 2012) in a sample comorbid for CD and ADHD, it also is possible that our overall sensitivity to CD deficits was the result of our studying noncomorbid CD. Indeed, our results are similar to those recently found in a sample of antisocial adults that had a relatively low proportion of participants who were diagnosed with ADHD in childhood (Sarkar et al., 2013).

Future research should attempt to determine how early such CD deficits can be detected, as this will have important implications for understanding the complex relationships between neuorobiological risk and actual disorder onset. In addition, if DTI-measured deficits can be tracked longitudinally in young CD-diagnosed children throughout adolescence to see whether they evolve in severity or localization, major questions regarding the type, timing and impact of these abnormalities on ongoing neural development could be clarified. Recent insights into genetic control of white matter development also represent a profitable line of research for psychiatric disorders such as CD (Feng, 2008). As research further characterizes the specific cellular mechanisms involved in building white matter axons, it should be possible to determine whether disruption of gene expression by environmental or other intrinsic biological factors produces the CD white matter abnormalities identified here.

The primary study strengths are the CD sample’s lack of comorbid symptomatology, its careful analyses to ensure CD deficits were unrelated to gender and verbal intelligence, its examination of multiple diffusivity indices, and its evidence for substantial group differences. The average effect size for significant FA results was d=1.01 (range 0.63–1.96), which represent relatively large and meaningful effects despite the modest sample size for a brain structure study. Reported effects for AD were lesser, but still of moderate magnitude (average AD d=0.87; range 0.34–1.73). Evidence linking specific FA deficits to CD severity was found as high as d=2.51. Although these associations consistently showed greater CD symptom counts reflected lower FA implying greater white matter microstructural disorganization, we also found evidence for a positive association between CD severity and white matter in bilateral anterior thalamic radiation. The significance of this latter finding is unclear, possibly reflecting a relationship between antisociality and enhanced information transmission between the thalamus and prefrontal cortex. Particularly given the more liberal statistical thresholds used, these associations require replication before being incorporated into neurobiological theories of antisociality. Study limitations include the low number of diffusion directions, which prevented confident use of tractography methods. Using a DTI MR sequence with a sufficiently high number of diffusion directions (e.g., 128) would make it possible to employ recent analytic advances in fiber tractography to link suspected poor inter-regional communication with specific brain region function, as was the goal in similar studies (Finger et al., 2012). It also is worth noting the TBSS approach is limited to analysis of major tracts, which might miss detecting abnormality in terminating white matter fibers that innervate grey matter within the cortical mantle. Although our post hoc comparison of CD age of onset ensured our findings were not weighted towards one subgroup or another, CD subgroups sizes were too small to conclude that age of CD onset is unrelated to white matter microstructure. Indeed, several exploratory effects were noted showing specific abnormalities in adolescent-onset CD. Moreover, strong conclusions about the presence or absence of CD age of onset differences should be tempered by the fact this was a cross-sectional study done in adolescence. A prospective study beginning in childhood not only would provide more confidence in age of onset findings (or lack thereof), but also would be important to disentangle any early CD white matter abnormalities from abnormal maturation that might interact in unpredictable ways. We also did not have information available regarding callous/unemotional traits, which represents an important CD subtype indicator (Frick et al., 2009; Moffitt & Caspi, 2001) with possibly distinct neural correlates. It also would be useful for future studies to replicate these findings in a comparison of CD participants to non-CD controls drawn directly from an adjudicated population, instead of the community. This would ensure that the findings cannot be attributed to unknown factors related to circumstances that led to legal involvement.

In conclusion, this study found evidence for extensive white matter microstructure abnormalities in CD adolescents that were unrelated to gender, verbal abilities, or CD age of onset. The widespread nature of the abnormalities raises the possibility of a generalized influence on white matter structure, possibly interacting with development or environment in ways that create a “disconnection” that underlies numerous social, emotional, or cognitive deficits found in antisocial samples. Indeed, various white matter regional abnormalities found in this study were consistent with emerging evidence for relationships between specific white matter tracts and various forms of cognition already known to be abnormal in antisocial groups. The pattern of widespread AD CD deficits in the absence of RD group differences directs future inquiry to study etiological mechanisms that affect axonal integrity rather than factors that disrupt myelination development. These DTI results stand in stark contrast to the typical lack of white matter volume differences in previous studies of antisocial samples (Huebner et al., 2008; Kruesi et al., 2004), highlighting the importance of considering microstructural properties when examining the role of white matter in studies of neuropsychiatric disorder liability.

Acknowledgments

Appreciation is offered to the Connecticut Court Support Services Division and Ms. Rena Goldwasser for assistance with recruitment, as well as research staff who collected and helped to prepare the data for analysis, including Ms. Sandra Navarro, Laura Miller, Abigail Quish, and Sara Beyor.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Angold A, Costello EJ, Erkanli A. Comorbidity. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 1999;40:57–87. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Basser PJ, Pierpaoli C. Microstructural and physiological features of tissues elucidated by quantitative-diffusion-tensor mri. J Magn Reson B. 1996;111:209–219. doi: 10.1006/jmrb.1996.0086. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blair RJ, Mitchell DG. Psychopathy, attention and emotion. Psychol Med. 2009;39:543–555. doi: 10.1017/S0033291708003991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Charlton RA, Barrick TR, Markus HS, Morris RG. Theory of mind associations with other cognitive functions and brain imaging in normal aging. Psychol Aging. 2009;24:338–348. doi: 10.1037/a0015225. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences. 2. Hillsdale, N.J: L. Erlbaum Associates; 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Craig MC, Catani M, Deeley Q, Latham R, Daly E, Kanaan R, Picchioni M, McGuire PK, Fahy T, Murphy DG. Altered connections on the road to psychopathy. Mol Psychiatry. 2009;14:946–953. 907. doi: 10.1038/mp.2009.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De Brito SA, Mechelli A, Wilke M, Laurens KR, Jones AP, Barker GJ, Hodgins S, Viding E. Size matters: Increased grey matter in boys with conduct problems and callous-unemotional traits. Brain. 2009;132:843–852. doi: 10.1093/brain/awp011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Du F, Ongur D. Probing myelin and axon abnormalities separately in psychiatric disorders using mri techniques. Frontiers in integrative neuroscience. 2013;7:24. doi: 10.3389/fnint.2013.00024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Feng Y. Convergence and divergence in the etiology of myelin impairment in psychiatric disorders and drug addiction. Neurochem Res. 2008;33:1940–1949. doi: 10.1007/s11064-008-9693-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger EC, Marsh A, Blair KS, Majestic C, Evangelou I, Gupta K, Schneider MR, Sims C, Pope K, Fowler K, Sinclair S, Tovar-Moll F, Pine D, Blair RJ. Impaired functional but preserved structural connectivity in limbic white matter tracts in youth with conduct disorder or oppositional defiant disorder plus psychopathic traits. Psychiatry Res. 2012;202:239–244. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2011.11.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finger EC, Marsh AA, Mitchell DG, Reid ME, Sims C, Budhani S, Kosson DS, Chen G, Towbin KE, Leibenluft E, Pine DS, Blair JR. Abnormal ventromedial prefrontal cortex function in children with psychopathic traits during reversal learning. Arch Gen Psychiatry. 2008;65:586–594. doi: 10.1001/archpsyc.65.5.586. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forstmann BU, Jahfari S, Scholte HS, Wolfensteller U, van den Wildenberg WP, Ridderinkhof KR. Function and structure of the right inferior frontal cortex predict individual differences in response inhibition: A model-based approach. J Neurosci. 2008;28:9790–9796. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.1465-08.2008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Frick PJ, Viding E. Antisocial behavior from a developmental psychopathology perspective. Dev Psychopathol. 2009;21:1111–1131. doi: 10.1017/S0954579409990071. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gao Y, Glenn AL, Schug RA, Yang Y, Raine A. The neurobiology of psychopathy: A neurodevelopmental perspective. Can J Psychiatry. 2009;54:813–823. doi: 10.1177/070674370905401204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glenn AL, Raine A. The neurobiology of psychopathy. Psychiatr Clin North Am. 2008;31:463–475. vii. doi: 10.1016/j.psc.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gold BT, Powell DK, Xuan L, Jicha GA, Smith CD. Age-related slowing of task switching is associated with decreased integrity of frontoparietal white matter. Neurobiol Aging. 2010;31:512–522. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2008.04.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffin SL, Mindt MR, Rankin EJ, Ritchie AJ, Scott JG. Estimating premorbid intelligence: Comparison of traditional and contemporary methods across the intelligence continuum. Arch Clin Neuropsychol. 2002;17:497–507. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hare R. The hare psychopathy checklist-revised. 2. Toronto, Ontario, Canada: Multi-Health Systems; 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hua K, Zhang J, Wakana S, Jiang H, Li X, Reich DS, Calabresi PA, Pekar JJ, van Zijl PC, Mori S. Tract probability maps in stereotaxic spaces: Analyses of white matter anatomy and tract-specific quantification. Neuroimage. 2008;39:336–347. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2007.07.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huebner T, Vloet TD, Marx I, Konrad K, Fink GR, Herpertz SC, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Morphometric brain abnormalities in boys with conduct disorder. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2008;47:540–547. doi: 10.1097/CHI.0b013e3181676545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jastak J, Wilkinson G. Wrat-3: Wide range achievement test administration manual. Wide Range, Inc; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Jenkinson M, Beckmann CF, Behrens TE, Woolrich MW, Smith SM. Fsl. Neuroimage. 2012;62:782–790. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.09.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones DK, Knosche TR, Turner R. White matter integrity, fiber count, and other fallacies: The do’s and don’ts of diffusion mri. Neuroimage. 2013;73:239–254. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.06.081. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karlsgodt KH, Niendam TA, Bearden CE, Cannon TD. White matter integrity and prediction of social and role functioning in subjects at ultra-high risk for psychosis. Biol Psychiatry. 2009;66:562–569. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaufman J, Birmaher B, Brent D, Rao U, Flynn C, Moreci P, Williamson D, Ryan N. Schedule for affective disorders and schizophrenia for school-age children-present and lifetime version (k-sads-pl): Initial reliability and validity data. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 1997;36:980–988. doi: 10.1097/00004583-199707000-00021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kruesi MJ, Casanova MF, Mannheim G, Johnson-Bilder A. Reduced temporal lobe volume in early onset conduct disorder. Psychiatry Res. 2004;132:1–11. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2004.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Merikangas KR, He JP, Burstein M, Swanson SA, Avenevoli S, Cui L, Benjet C, Georgiades K, Swendsen J. Lifetime prevalence of mental disorders in u.S. Adolescents: Results from the national comorbidity survey replication--adolescent supplement (ncs-a) J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2010;49:980–989. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller GA, Chapman JP. Misunderstanding analysis of covariance. J Abnorm Psychol. 2001;110:40–48. doi: 10.1037//0021-843x.110.1.40. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell DG, Colledge E, Leonard A, Blair RJ. Risky decisions and response reversal: Is there evidence of orbitofrontal cortex dysfunction in psychopathic individuals? Neuropsychologia. 2002;40:2013–2022. doi: 10.1016/s0028-3932(02)00056-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. Adolescence-limited and life-course-persistent antisocial behavior: A developmental taxonomy. Psychol Rev. 1993a;100:674–701. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE. The neuropsychology of conduct disorder. Development and Psychopathology. 1993b;5:133–151. [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Arseneault L, Jaffee SR, Kim-Cohen J, Koenen KC, Odgers CL, Slutske WS, Viding E. Research review: Dsm-v conduct disorder: Research needs for an evidence base. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2008;49:3–33. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2007.01823.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Caspi A. Childhood predictors differentiate life-course persistent and adolescence-limited antisocial pathways among males and females. Dev Psychopathol. 2001;13:355–375. doi: 10.1017/s0954579401002097. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moffitt TE, Lynam D. Neuropsychology of delinquent behavior: Implications for understanding the psychopath. In: Fowles D, Sutker P, Goodman S, editors. Psychopathy and antisocial personality: A developmental perspective. Progress in experimental personality and psychopathology research. Vol. 18. New York: Springer; 1994. pp. 233–262. [Google Scholar]

- Mori S, Wakana S, Nagae-Poetscher LM, van Zijl PCM. Mri atlast of human white matter. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier, B.V; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Jarrett MA, Grills-Taquechel AE, Hovey LD, Wolff JC. Comorbidity as a predictor and moderator of treatment outcome in youth with anxiety, affective, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional/conduct disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008a;28:1447–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ollendick TH, Jarrett MA, Grills-Taquechel AE, Hovey LD, Wolff JC. Comorbidity as a predictor and moderator of treatment outcome in youth with anxiety, affective, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and oppositional/conduct disorders. Clin Psychol Rev. 2008b;28:1447–1471. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passamonti L, Fairchild G, Fornito A, Goodyer IM, Nimmo-Smith I, Hagan CC, Calder AJ. Abnormal anatomical connectivity between the amygdala and orbitofrontal cortex in conduct disorder. PloS one. 2012;7:e48789. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0048789. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Philippi CL, Mehta S, Grabowski T, Adolphs R, Rudrauf D. Damage to association fiber tracts impairs recognition of the facial expression of emotion. J Neurosci. 2009;29:15089–15099. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.0796-09.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quickfall J, Crockford D. Brain neuroimaging in cannabis use: A review. J Neuropsychiatry Clin Neurosci. 2006;18:318–332. doi: 10.1176/jnp.2006.18.3.318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K. “Cool” inferior frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus “hot” ventromedial orbitofrontal-limbic dysfunction in conduct disorder: A review. Biol Psychiatry. 2010;69:e69–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K. “Cool” inferior frontostriatal dysfunction in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder versus “hot” ventromedial orbitofrontal-limbic dysfunction in conduct disorder: A review. Biol Psychiatry. 2011;69:e69–87. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2010.09.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Halari R, Cubillo A, Mohammad AM, Scott S, Brammer M. Disorder-specific inferior prefrontal hypofunction in boys with pure attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder compared to boys with pure conduct disorder during cognitive flexibility. Hum Brain Mapp. 2010;31:1823–1833. doi: 10.1002/hbm.20975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Halari R, Smith AB, Mohammad M, Scott S, Brammer MJ. Shared and disorder-specific prefrontal abnormalities in boys with pure attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder compared to boys with pure cd during interference inhibition and attention allocation. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2009a;50:669–678. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2008.02022.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Halari R, Smith AB, Mohammed M, Scott S, Giampietro V, Taylor E, Brammer MJ. Dissociated functional brain abnormalities of inhibition in boys with pure conduct disorder and in boys with pure attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Am J Psychiatry. 2008;165:889–897. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.07071084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rubia K, Smith AB, Halari R, Matsukura F, Mohammad M, Taylor E, Brammer MJ. Disorder-specific dissociation of orbitofrontal dysfunction in boys with pure conduct disorder during reward and ventrolateral prefrontal dysfunction in boys with pure adhd during sustained attention. Am J Psychiatry. 2009b;166:83–94. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.2008.08020212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkar S, Craig MC, Catani M, Dell’acqua F, Fahy T, Deeley Q, Murphy DG. Frontotemporal white-matter microstructural abnormalities in adolescents with conduct disorder: A diffusion tensor imaging study. Psychol Med. 2013;43:401–411. doi: 10.1017/S003329171200116X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmahmann J, Pandya D. Fiber pathways of the brain. New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Jenkinson M, Johansen-Berg H, Rueckert D, Nichols TE, Mackay CE, Watkins KE, Ciccarelli O, Cader MZ, Matthews PM, Behrens TE. Tract-based spatial statistics: Voxelwise analysis of multi-subject diffusion data. Neuroimage. 2006;31:1487–1505. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2006.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith SM, Nichols TE. Threshold-free cluster enhancement: Addressing problems of smoothing, threshold dependence and localisation in cluster inference. Neuroimage. 2009;44:83–98. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.03.061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SK, Sun SW, Ju WK, Lin SJ, Cross AH, Neufeld AH. Diffusion tensor imaging detects and differentiates axon and myelin degeneration in mouse optic nerve after retinal ischemia. Neuroimage. 2003;20:1714–1722. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2003.07.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SK, Sun SW, Ramsbottom MJ, Chang C, Russell J, Cross AH. Dysmyelination revealed through mri as increased radial (but unchanged axial) diffusion of water. Neuroimage. 2002;17:1429–1436. doi: 10.1006/nimg.2002.1267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Song SK, Yoshino J, Le TQ, Lin SJ, Sun SW, Cross AH, Armstrong RC. Demyelination increases radial diffusivity in corpus callosum of mouse brain. Neuroimage. 2005;26:132–140. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2005.01.028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens MC, Haney-Caron E. Comparison of brain volume abnormalities between adhd and conduct disorder in adolescence. J Psychiatry Neurosci. 2012;37:389–398. doi: 10.1503/jpn.110148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strauss E, Sherman EMS, Spreen O. A compendium of neuropsychological tests: Administration, norms, and commentary. 3. New York: Oxford University Press; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Sundram F, Deeley Q, Sarkar S, Daly E, Latham R, Craig M, Raczek M, Fahy T, Picchioni M, Barker GJ, Murphy DG. White matter microstructural abnormalities in the frontal lobe of adults with antisocial personality disorder. Cortex. 2012;48:216–229. doi: 10.1016/j.cortex.2011.06.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vloet TD, Konrad K, Huebner T, Herpertz S, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Structural and functional mri-findings in children and adolescents with antisocial behavior. Behav Sci Law. 2008a;26:99–111. doi: 10.1002/bsl.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vloet TD, Konrad K, Huebner T, Herpertz S, Herpertz-Dahlmann B. Structural and functional mri-findings in children and adolescents with antisocial behavior. Behav Sci Law. 2008b;26:99–111. doi: 10.1002/bsl.794. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weber S, Habel U, Amunts K, Schneider F. Structural brain abnormalities in psychopaths-a review. Behav Sci Law. 2008;26:7–28. doi: 10.1002/bsl.802. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang Y, Raine A. Prefrontal structural and functional brain imaging findings in antisocial, violent, and psychopathic individuals: A meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res. 2009;174:81–88. doi: 10.1016/j.pscychresns.2009.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]