Abstract

Objectives

This study assesses (a) the reciprocity between mental and physical health pre- and postretirement, and (b) the extent to which these associations vary by race.

Method

Data are from the 1994 to 2008 waves of the Health and Retirement Study.

Results

Analyses based on structural equation modeling reveal that depression and physical health exert reciprocal effects for Whites pre- and postretirement. For Blacks preretirement, physical limitations predict changes in depression but there is no evidence of the reverse association. Further, the association between physical limitations and changes in depressive symptoms among Blacks is no longer significant after retirement.

Discussion

The transition into retirement alleviates the translation of physical limitations into depressive symptoms for Blacks only. The findings underscore the relevance of retirement for reciprocity between mental and physical health and suggest that the health implications associated with this life course transition vary by race.

Keywords: retirement, health, race

Introduction

The co-occurrence of mental and physical health problems is a major public health issue in the United States, as it constitutes significant economic, social, and personal costs (Gatchel, 2004). The relationship between mental and physical health has been studied through the disablement process framework, which emphasizes that current health affects future health (Lawrence & Jette, 1996). This theoretical framework is supported by studies demonstrating reciprocal effects between depression and physical health (Aneshensel, Frerichs, & Huba, 1984; Gayman, Brown, & Cui, 2011; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005). Although it is recognized that major life course transitions may speed up or slow down the disablement process (Verbrugge & Jette, 1994), the extent to which the reciprocity between mental and physical health is altered by life transitions remains unknown. For instance, it is unclear whether the reciprocity between mental and physical health is altered after transitioning into retirement.

Race differences in the relationship between retirement and health have received even less attention. This is surprising given that there are reasons to anticipate race differences in the role of retirement for this reciprocal relationship. For example, because Blacks disproportionately experience more disadvantaged work histories and occupy jobs with lower wages and fewer health benefits (McAdoo, 2007; McLoyd, Hill, & Dodge, 2005), they may be uniquely impacted by the transition into retirement. Specifically, the potential benefits related to retirement that may mitigate the translation of mental distress into physical decline, and vice versa, may only apply to those who are socially marginalized. The extent to which retirement differentially shapes the reciprocal relationship between mental and physical health for Blacks and Whites, however, remains yet to be explored.

The current study advances existing research in two important ways. First, we use longitudinal data from a nationally representative sample of retirement-aged adults (Health and Retirement Study [HRS], 1994–2008) to evaluate the reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and physical limitations pre- and postretirement. Second, we test the extent to which the relationship between mental and physical health varies by race before and after retirement.

Background

Reciprocity Between Mental and Physical Health

The disablement process has proven useful for framing the relationship between mental and physical health (Lawrence & Jette, 1996). An underlying tenet of this process is that current health influences future health and that one type of health condition likely affects another type of health condition. For example, depression may increase risk for physical limitations through reduced interest in physical activities and social relationships. Concurrently, physical limitations can impede one’s capacity to fulfill the requirements of social roles and responsibilities, which may result in depressive mood. Indeed, recent studies employing longitudinal data have demonstrated that depression and physical health problems exert reciprocal effects over time (Gayman et al., 2011; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005; Meeks, Murrell, & Mehl, 2000; Ormel, Rijsdijk, Sullivan, van Sonderen, & Kempen, 2002). However, the extent to which these reciprocal effects are similar before and after major life course transitions, such as retirement, is unknown.

Retirement and Health

Viewed as “a primary motive for retirement” (Pienta & Hayward, 2002), poor mental and physical health have been linked to lower levels of labor force participation and early retirement (Braden, Zhang, Zimmerman, & Sullivan, 2008; Doshi, Cen, & Polsky, 2008; Kim & DeVaney, 2005). The effect of retirement on health, however, is less clear, in part because of the complex and dynamic nature of this transition (Shapiro & Yarborough-Hayes, 2008). Although some studies have found few mental or physical health differences between retirees and nonretirees (Drentea, 2002; Herzog, House, & Morgan, 1991; Midanik, Soghikian, & Tekawa, 1995; Ross & Drentea, 1998), there is evidence linking retirement to better mental and physical health (Evenson, Rosamond, Cai, Diez-Roux, & Brancati, 2002; McGarry, 2004; Mutchler, Burr, Massagli, & Pienta, 1999; Reitzes, Mutran, & Fernandez, 1996). To date, no studies have assessed the role of retirement for the reciprocal relationship between depression and physical limitations.

Consistent with the disablement process (Verbrugge & Jette, 1994), the reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and physical limitations may be altered by the sociocontextual changes associated with the transition into retirement. Given that retirement may mean the elimination of work stress, reduction in role conflict and increased healthcare access through Social Security and Medicare, this transition may mitigate the reciprocal relationship between mental and physical health for at least three reasons. First, to the extent that depressive symptoms translates into physical limitations, or vice versa, by limiting one’s capacity to fulfill the worker role, retirement may be accompanied by a reduction in stress exposure, which is known to mediate the relationship between mental and physical health (Gayman, et al., 2011). Second, instead of having to juggle between paid work and nonpaid work roles, retirement may enable people to focus their attention on their health, as well as activities that are personally meaningful and therefore, more satisfying. This flexibility to focus one’s efforts on one’s health may prevent the translation of depressive symptoms into physical limitations, and vice versa. And, third, increased access to healthcare through Social Security and Medicare may provide individuals with treatment that may deter the translation of mental health problems into physical health problems, and vice versa.

Race, Health, and Retirement

Although there is considerable evidence demonstrating that Blacks have poorer mental and physical health than their White counterparts (Williams & Mohammed, 2009; Williams & Sternthal, 2010), few studies have assessed race differences in the reciprocal relationship between depression and physical limitations. In one exception, Kelley-Moore & Ferraro (2005) found that the cyclical nature between mental and physical health over time is similar for Blacks and Whites. While this provides an important first step in assessing race patterns in health decline, much of this work has used samples of largely White older adults (e.g., Alexopoulos et al., 1996; Allair et al., 1999; Aneshensel et al., 1984; Lyness, King, Cox, Yoediono, & Caine, 1999; Simons, McCallum, Friedlander, & Simons, 2000). Moreover, it is unclear if and how the transition out of paid work affects the reciprocity between mental and physical health differentially for Blacks and Whites.

While research examining the links between health, retirement, and race is limited, there are reasons to anticipate race differences in the reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and physical limitations after transitioning into retirement. For example, the translation of depressive symptoms into physical limitations, and vice versa, may be reduced after retirement more so for Blacks because they are more likely than Whites to experience work stressors and occupy jobs that do not offer health insurance (Leigh & Huff, 2007; McAdoo, 2007; McLoyd et al., 2005; Short & Weaver, 2008). Jobs with high psychological demands and low levels of decision-making capacity are stressful and adversely affect health because they limit the experience of autonomy at work, while exerting continued pressure (Johnson & Hall, 1988; Karasek & Theorell, 1990). Because retirement may reduce (or remove) disproportionately higher levels of work stressors and increase access to health care for Blacks, Blacks may experience greater health benefits from this transition than Whites.

Summary and Hypotheses

Although recent studies demonstrate that depression and physical health problems exert reciprocal effects over time (Gayman et al., 2011; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005), it is unclear whether this reciprocal relationship varies across the retirement transition, and whether there are race differences in the role of retirement for the mental-physical health relationship. Based on the disablement process theory and prior research, we test the following hypotheses:

-

Hypothesis 1 (H1)

The transition into retirement is associated with better mental and physical health for both Whites and Blacks, but this health improvement is even greater for Blacks.

-

Hypothesis 2 (H2)

Depressive symptoms and physical limitations share reciprocal effects for both Whites and Blacks preretirement.

-

Hypothesis 3 (H3)

The reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and physical limitations persists for Whites but discontinues for Blacks after retirement.

Method

Sample

Analyses are based on data from the 1994 to 2008 waves of the HRS, a nationally representative panel study designed to investigate the physical and mental health, financial well being, and work behavior of older noninstitutionalized Americans. The core HRS sample began by interviewing 12,654 people ages 51 to 61 in 1992 (as well as their spouses), and over sampled Blacks, Hispanics, and Floridians. Follow-up interviews were done every 2 years (HRS, 2008; Juster & Suzman, 1995; RAND Center for the Study of Aging, 2008).

For purposes of the current investigation, the working sample was limited in several ways. First, because the primary sampling unit was the household, there are instances where respondents are interviewed by a proxy member of the household. In these cases, questions of mental health were not asked. Because depression is a central concern for this study, respondents were excluded in waves where their responses were given via proxy. Second, because key variables were measured differently in 1992 than in subsequent waves, the 1992 wave was excluded from the present study. Third, respondents without valid data on study outcomes (11.6% of the original sample) were also excluded from the analyses. Fourth, given that comparisons between Black and White Americans are a primary focus to this research, those self-identifying as Hispanic or of “other” race also were excluded from the sample. Fifth, although the HRS has added several additional cohorts to the original study, the analyses presented here rely solely on the original HRS sample. Sixth, since our analysis focuses on the health of individuals during the transition from work, we restricted our working sample to those individuals who were employed in the first wave of analysis and left the labor force before the last wave of the study. Finally, in order to capture as many retirement transitions as possible we included people with at least three consecutive waves of data surrounding the retirement transition (i.e., two before and one after, or one before and two after). Had we not done so, the sample size would have decreased by two thirds. Sensitivity analyses, however, restricted to only individuals with valid responses two waves pre and postretirement (N = 1,232) produced similar results in terms of the magnitude, significance, and direction of the findings presented in this study. After making these adjustments, the working sample includes 3,264 individuals, who are observed, on average, 3.6 waves.

Measures

Retirement

The transition into retirement was operationalized using self-reports on labor force status at each study wave. Respondents reported working, being retired, or disability. Respondents were coded as exiting the labor force in a given wave if they went from labor force status of working (either full or part time) to retired (either partially or fully) or disabled in a subsequent wave. A flag was created for those who reported exiting the labor force due to a disability. In this sample, the number of people exiting the labor force at each wave included 894 between 1994 and 1996, 645 between 1996 and 1998, 571 between 1998 and 2000, 472 between 2000 and 2002, 310 between 2002 and 2004, 234 between 2004 and 2006, and 138 between 2006 and 2008.

Depressive Symptoms

Depressive symptomatology was measured using a shortened version of the commonly employed and reliable Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression (CES-D) scale (Radloff, 1977). Respondents provided yes (1) or no (0) responses to whether over the past week they: felt depressed; felt everything was an effort; sleep was restless; were happy (reverse coded); felt lonely; felt sad; enjoyed life (reverse coded); and could not get going. The eight dichotomous items were summed and divided by the total number of items (α = 0.77). Thus, the measure represents the proportion of depressive symptoms from which the individual responded affirmatively. Those with missing data on any of the eight items (5.9%) were treated as missing for that study wave. There were no racial differences in the percent missing. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess variations in measurement specifications. Specifically, one set of analysis employed a simple summation of all eight items and treated those with any missing items as missing for that study wave. A second set of analysis also employed a simple summation but retained all individuals with missing data on one or more items. Findings from the sensitivity analyses were substantively identical to the results reported in the tables/figures.

Physical Limitations

Problems with physical limitations were measured using a shortened version of the activities of daily living (ADL) / instrumental activities of daily living (IADL) scales, commonly used in comparable studies measuring physical health (Fries, Spitz, Kraines, & Holman, 1980; Nagi, 1976; Rosow & Breslau, 1966). Originally, respondents were coded “1” if they reported any difficulty with: walking one block; sitting for two hours; getting up from a chair; climbing one flight of stairs; stooping, kneeling, or crouching; lifting or carrying 10 pounds; picking up a dime from the floor; reaching or extending one’s arms; and pushing or pulling a large object. The nine dichotomous items were summed (α = 0.77). Thus, the measure represents the proportion of physical limitations from which the individual responded affirmatively. Those with missing data on any of the nine items (6.3%) were treated as missing for that study wave. There were no racial differences in the percent missing. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to assess variations in measurement specifications, as described with the depressive symptoms measure. Specifically, one set of analysis employed a simple summation of all nine items and treated those with any missing items as missing for that study wave. A second set of analysis also employed a simple summation but retained all individuals with missing data on one or more items. Findings from the sensitivity analyses were substantively identical to the results reported in the tables/figures.

Control Variables

Several sociodemographic measures were used in these analyses including race (White = 1 and Black = 0), gender (men = 1 and women = 0), education (in years), and age in 1994 (in years). Because the relationship between depression and physical limitations may vary depending on whether individuals exit the labor force due to a disability, we controlled for disability exit (coded “1” for those individuals who reported their labor force status as working in wavet−1 and as disabled in wavet). Given that Blacks are more likely than Whites to experience disadvantaged work histories (McAdoo, 2007; McLoyd et al., 2005) and disadvantaged work histories are predictive of higher rates of mortality (Marshall, Clarke, & Ballantyne, 2001; Pavalko, Elder, & Clipp, 1993), racial differences in mortality may be an important factor in explaining the relationship between depression and physical limitations. Thus SEM analysis controls for whether people died during the observation period.

Analysis Plan

In order to understand racial differences in mental and physical health pre- and postretirement, we first examine descriptive statistics for depressive symptoms and physical limitations by race (Table 1). Racial differences in each of these variables are tested using two-tailed t-tests. Then, to simultaneously examine reciprocal effects for depressive symptoms and physical limitations pre- and postretirement, we utilize path analysis in a SEM framework. Since we are interested in race differences, multiple group models are employed along with χ2 difference tests to determine whether (a) the reciprocal effects between physical limitations and depressive symptoms differ significantly pre- and postretirement among Blacks and Whites and (b) whether the effects of these multiple pathways differ significantly across race (Figures 1 and 2). The χ2 tests compare overall fit in models where path effects are estimated freely (or separately) across groups to those where the effects are constrained to be equal across groups, thus yielding significance tests of these differences (Bollen, 1989). All path analyses are conducted using Mplus Version 4.21 (Muthén & Muthén, 2004).

Table 1.

Depressive symptoms and physical limitations by race within study wave pre and postretirement.

| Preretirement

|

Postretirement

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Wave 1

|

Wave 2

|

Wave 3

|

Wave 4 | |||||

| White | Black | White | Black | White | Black | White | Black | |

| Depressive symptoms | 0.11** (0.18) | 0.19 (0.23) | 0.12** (0.20) | 0.19 (0.24) | 0.13** (0.21) | 0.20 (0.24) | 0.14** (0.21) | 0.20 (0.24) |

| Physical limitations | 0.11* (0.16) | 0.14 (0.20) | 0.13* (0.18) | 0.16 (0.20) | 0.16** (0.21) | 0.21 (0.24) | 0.17** (0.21) | 0.21 (0.25) |

| N | 1,750 | 305 | 2,417 | 410 | 2,417 | 418 | 2,175 | 360 |

Notes. Shown are the proportion of depressive symptoms and physical limitations from which the individual respondent affirmatively. Wave 1 is two waves before transitioning out of the labor force, Wave 2 is the wave prior to that transition, Wave 3 is the wave after the transition, and Wave 4 is two waves after transitioning out of the labor force. Tests for differences between Blacks and Whites conducted using two-tailed t-tests.

p < .05.

p < .001.

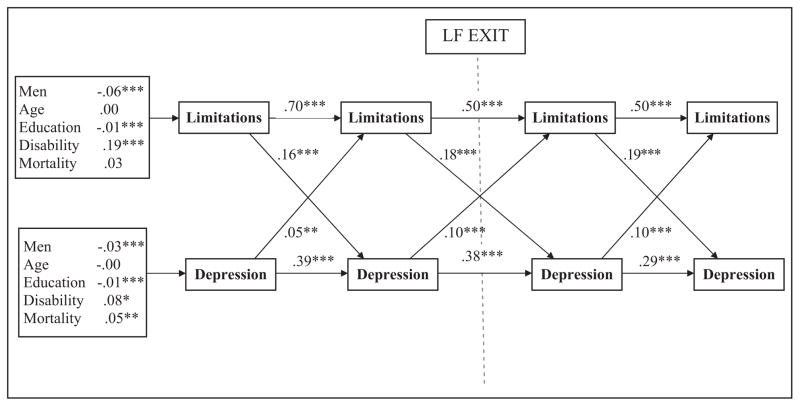

Figure 1.

Reciprocal relationship between functional limitations and depressive symptoms across labor force exit: White.

Note: All coefficients are unstandardized. Lagged effects within time varying variables and covariances between limitations and depression at the first and last waves were modeled but not shown. Group N = 2,765. Overall N = 3,264. Overall Model Fit: χ2 = 526.79, df = 72. Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.90, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

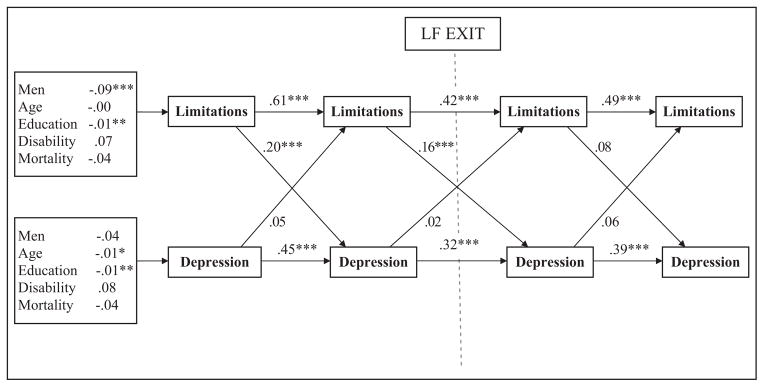

Figure 2.

Reciprocal relationship between functional limitations and depressive symptoms across labor force exit: Black.

*Note: All coefficients are unstandardized. Lagged effects within time varying variables and covariances between limitations and depression at the first and last waves were modeled but not shown. Group N = 499. Overall N = 3,264. Overall Model Fit: χ2 = 526.79, df = 72. Tucker–Lewis Index (TLI) = 0.90, Comparative Fit Index (CFI) = 0.95, Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA) = 0.06. *p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

Cases with missing data on the dependent variables were excluded from the analysis and cases with missing data on the independent variables were handled using Full Information Maximum Likelihood (FIML) estimation, which allows a likelihood estimate to be computed for each individual given all available information for that individual. The FIML estimator is preferable over multiple other methods of handling missing data as it maintains the asymptotic properties of Maximum Likelihood estimators under the less restrictive assumption of missing at random (MAR) (Bollen & Curran, 2006).

Supplementary analyses assess whether the race patterns observed in the reciprocal relationship between mental and physical health pre- and postretirement are independent of known covariates. The physical difficultly of the job from which respondents exited is measured as the sum of three dichotomously coded (yes = 1) measures: job required lifting heavy loads, job required lots of physical effort, and job required stooping, kneeling, or crouching. The stressfulness of the job is measured with one dichotomous item of whether the job involved a lot of stress. Insurance coverage was measured using one dichotomous indicator of whether people had employer provided insurance or public insurance in the wave prior to exiting the labor force and indicators of both public and private insurance in the wave postretirement.

Results

Bivariate Statistics

Table 1 provides descriptive statistics for depressive symptoms and physical limitations by race pre- and postretirement. Results indicate that depressive symptoms and physical limitations increased for both Blacks and Whites over the study period. However, Blacks responded affirmatively to significantly more depressive symptoms and physical limitations than Whites at each wave, pre- and postretirement. Analysis, not shown, also revealed that a greater proportion of Blacks (0.05) than Whites (0.02) reported retiring due to a physical disability (t = 3.84, p = .000). Taken together bivariate results indicate that Blacks generally report worse of both mental and physical health pre- and postretirement.

Health Reciprocity Pre- and Postretirement

The results of the multiple group path analysis are presented in Figures 1 and 2 for White and Black retirees, respectively. In examining the effects of control variables on the initial levels of physical limitations and depressive symptoms, men generally reported fewer physical limitations (0.06 reduced proportion of limitations for Whites, 0.09 reduced proportion for Blacks) and reported fewer depressive symptoms among Whites only. Education was protective across race categories, reducing the proportion of symptoms and limitations by 0.01 each per year. Individuals dying throughout the observation period had fewer depressive symptoms, but this was only observed for Whites.

There are a number of noteworthy findings when examining depressive symptoms and physical limitations pre- and postretirement, the reciprocity of these relationships, and race differences in these relationships. First, consistent with bivariate results, estimated mean levels of depressive symptoms (χ2 diff. = 13.16[df = 4], p = .01) and physical limitations (χ2 diff. = 10.68[df = 4], p = .03) were higher for Blacks than Whites across all waves, controlling for demographic, socioeconomic factors, and mortality. Second, the increases in depressive symptoms and physical limitations during the transition to retirement (shown in Table 1) were accounted for by study controls and prior health. In addition, adjusting for controls and prior health revealed important race differences in the change in depressive symptoms and physical limitations during the retirement transition. Specifically, difference tests reveal that after controls were included, Whites experienced a significant decrease in estimated depressive symptoms from 0.06 to 0.04 in the proportion of symptoms they reported (χ2 diff. = 5.49[df = 1], p = .02) across the retirement transition but Blacks did not, having estimated mean depression symptoms at 0.08 and 0.08, respectively (χ2 diff. = 0.01[df = 1], p = .92). Neither Whites (χ2 diff. = 0.23[df = 1], p = .63) nor Blacks (χ2 diff. = 3.12 [df = 1], p = .08) reported significant changes in physical limitations during the retirement transition once controls were included (White mean proportion of limitations = 0.05 and 0.05, Black mean = 0.06 and 0.09). This suggests that even though neither group reported significant changes in their physical limitations across this transition, Whites received a slight overall mental health benefit from retirement but Blacks, on average, did not.

Examining the effects of depressive symptoms on changes in physical limitations, results indicate a significant positive effect of mental health on physical functioning for Whites pre- and postretirement (lagged coefficients = 0.05, 0.10, 0.10) but that this mental to physical health pathway is not significant for Blacks either pre- or postretirement. However, the difference in the effects across race is not significant (χ2 diff. = 4.13[df = 3], p = .25). Together the evidence indicates that the relationship between depressive symptoms and changes in physical limitations for Whites is significant and consistent before and after retirement but there are no corresponding significant effects among Blacks, and it is unclear whether the findings are significantly different between Whites and Blacks. Therefore, while there is clear evidence among Whites, there is no clear evidence of an association between depressive symptoms and changes in physical limitations among Blacks.

Net of demographic and socioeconomic, and mortality effects, physical limitations had a significant positive effect on depressive symptoms for both groups prior to retirement (lagged coefficient = 0.16 for Whites and .20 for Blacks). Further, χ2 difference tests reveal that these effects were not significantly different across races preretirement (χ2 diff. = 0.30[df = 1], p = .58). Thus, physical limitations predicted changes in depressive symptoms for both Blacks and Whites preretirement. Assessing the effects of physical limitations on depressive symptoms pre- versus postretirement within each racial group, the effect among Whites increased slightly from 0.16 to 0.19, but remained significant. The χ2 difference test revealed that this difference over time was not significant among Whites (χ2 diff. = 0.01[df = 1], p = .92). Among Blacks, however, the effect of physical limitations on depressive symptoms decreased by more than half (from 0.20 to 0.08) and the effects became nonsignificant postretirement. The decrease in the effect was significant (χ2 diff. = 3.92 [df = 1], p = .048). We further tested the significant effect of physical limitations on depressive symptoms postretirement among Whites (lagged coefficient = 0.19) against the nonsignificant effect among Blacks (lagged coefficient = 0.08) and found the difference to be significant (χ2 diff. = 4.99[df = 1], p = .03). Thus, although there was no clear race difference before retirement, the impact of physical limitations on depressive symptoms after retirement was significantly lower for Blacks.

Based on Black-White differences in work histories and social program benefits (Leigh & Huff, 2007; McAdoo, 2007; McLoyd et al., 2005; Short & Weaver, 2008), supplemental analyses were conducted to assess whether the race patterns observed in the reciprocal relationship between mental and physical health pre- and postretirement are independent of other covariates. Specifically, adjusting for physical difficultly of the job from which the respondent exited from, stressfulness of the job from which the respondent exited from, employer or public health insurance coverage prior to retirement, and public health insurance coverage postretirement, the race patterns in the reciprocal association between mental and physical health pre- and postretirement were statistically and substantively identical to those reported above.

Discussion

The disablement process framework underscores the importance of current health for future health and the role of sociocontextual changes for health-related processes (Verbrugge & Jette, 1994). While studies have demonstrated reciprocal effects between depression and physical health (Aneshensel, Frerichs, & Huba, 1984; Gayman, Brown, & Cui, 2011; Kelley-Moore & Ferraro, 2005), no studies have assessed whether the reciprocity between mental and physical health is altered by major life course transitions. Because retirement is a major life course transition in late adult life, the current study contributed to current knowledge by (a) exploring the reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and physical limitations pre- and postretirement, and (b) assessing whether this reciprocal relationship varies by race.

Our first hypothesis stated that the transition into retirement is associated with better mental and physical health for both Whites and Blacks, but this health improvement would be even greater for Blacks. In partial support of our hypothesis, there was evidence indicating that leaving the labor force does, indeed, come with a mental health advantage. While this remains consistent with prior research (Evenson et al., 2002; McGarry, 2004; Mutchler et al., 1999; Reitzes et al., 1996), our study reveals that the mental health benefit from retirement is limited to Whites only. Although retirement often is reflective of reduced work-family conflict, decreased stress, and increased time for leisure, leaving the labor force may also mean reduction in monthly income. While both Whites and Blacks likely suffer from loss of adequate income after leaving the labor force, given that a greater proportion of Blacks are economically deprived across the life course, the reduced income in retirement may pose a greater challenge for Black than White older adults. This reflects the central premise of the resource perspective model (Hobfoll, 2002) that posits that the ease of adjustment, including health outcomes is the direct result of the individual’s access to resources. Specifically, when people have more resources to fulfill the needs they value in retirement, they will experience greater mental health benefits from this transition. Given the instability associated with unemployment and lower wages, researchers also have argued that “retirement” as it is popularly conceived (i.e., a period of consumption and leisure after career employment) is not a salient and personally satisfying event for racial minorities (Gibson 1987; Quinn and Kozy 1996). If retirement does not translate into financial comfort but instead adds to economic hardships, it is only likely then that leaving the labor force may not translate into any psychological benefits for Black older adults.

In the second hypothesis, we posited that depressive symptoms and physical limitations share reciprocal effects for both Whites and Blacks preretirement. Contrary to our expectations, the results indicate that depressive symptoms and physical limitations exert reciprocal effects prior to retirement for Whites but not Blacks. For Blacks preretirement, physical limitations were linked to changes in depressive symptoms but there was no observed relationship between depressive symptoms and changes in physical limitations. Because Blacks experience high rates of physical health problems (Hummer, Benjamin, & Rogers, 2004), symptoms of depression may have a relatively limited capacity to significantly reduce physical functioning among Blacks. Thus the observed patterns may reflect racial inequalities in physical health rather than a physical health advantage stemming from retirement for Blacks. However, it should be noted that a failure to observe a link between depressive symptoms and changes in physical limitations among Blacks may be due to the relatively small number of Black participants compared to Whites.

The third hypothesis stated that the reciprocal relationship between depressive symptoms and physical limitations would persist after retirement for Whites but not for Blacks. Our results offered support for this hypothesis. We found that for Whites the reciprocity between depressive symptoms and physical limitations persisted after leaving the labor force. For Blacks, however, the preretirement relationship between physical limitations and changes in depressive symptoms was no longer observed after retirement. In partial support of our hypothesis, this finding reveals that the reciprocal influence between mental and physical health both before and after retirement varies by race. Specifically, for Whites the transition into retirement did not alter the existing reciprocal relationship between mental and physical health but for Blacks the transition into retirement did alleviate the translation of physical limitations into depressive symptoms after retirement.

We speculated that the way retirement affects the relationship between mental and physical health differentially for Blacks and Whites is through contextual differences in job type, level of work stress, and availability of health insurance. In this vein, we conducted supplementary analyses adjusting for work histories involving physically demanding and stressful jobs, as well as pre- and postretirement health insurance. Surprisingly, however, these factors did not explain the race differences in the role of retirement for the link between mental and physical health. While not within the scope of the present investigation, future studies should consider additional factors related to work stress, namely perceptions of discrimination. Racial discrimination among African Americans has been linked to increased risk for physical health problems (Williams & Mohammed, 2009). It is likely then that perceptions of discrimination at the work place may result in physical health problems, which in turn may translate into depressive symptoms. Because retirement may eliminate work-related perceptions of discrimination, leaving the labor force may help mitigate the translation of physical health problems into mental distress.

Although in our study the overall mental health benefits stemming from retirement were limited to Whites, the transition into retirement does have health benefits for Blacks by reducing the risk of physical limitations translating into depressive symptoms. While one might be optimistic about such patterns in relation to reducing racial disparities in health, raising the average age of retirement benefits may delay this health benefit for Blacks. Although it is premature to make specific policy recommendations, especially given this is the first study to investigate the topic on hand, the findings underscore the importance of considering what such a reform would mean to disadvantaged segments of America—in terms of opportunities, constraints, and well being.

The “graying” of the workforce calls attention to the need to examine how life course transition, such as retirement, are related to health in later life. Efforts to increase the age when retirement benefits commence, due to both cohort trends and financial constraints as evidenced by the recent economic recession, is likely to result in individuals working longer into late life. It also means that individuals exposed to greater work stress are likely to experience such stressor for more prolonged periods of time. African Americans and other racial minorities often have qualitatively different experiences of both employment and retirement than their White counterparts; however, relatively little is known about the ways in which retirement influences health in later adulthood among racially marginalized groups. Considering the paucity of research that has explored the relationship between retirement, race, and health, findings presented here require replication.

Limitations and Future Directions

Our findings should be interpreted in light of important limitations. First, while the present study accounts for those exiting the labor force due to a physical disability and prior health, research has shown that involuntary job loss and retirement due to disability are associated with lower self-rated health and more depressive symptoms independent of baseline health (Burgard, Brand, & House, 2007; Gallo, Bradley, Siegel, & Kasl, 2000; Solinge, 2007). Thus further research is needed to assess the role of involuntary job loss and retirement due to disability for the reciprocal relationship between mental and physical health pre- and postretirement, as well as race differences in these relationships. Second, the importance of retirement for health also is shaped by the meaning people attach to this life course transition and the salience of the worker role to their identity (Herzog et al., 1991; Kim & Moen, 2002; Solinge & Henkens, 2005). Thus the reason for exiting the work force, salience of the worker identity, and the meaning attached to this transition are all important factors to consider when assessing the role of retirement for the reciprocal relationship between mental and physical health, as well as race differences in this relationship. Third, given that the current and projected U.S. economic environment will likely mean delays to retirement and/or returning to work for many older adults (Sterns & Chang, 2010), studies are needed to assesses the role of trends in delaying retirement and returning to work after retirement on the relationship between mental and physical health.

Acknowledgments

Funding

The authors received no financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Footnotes

Reprints and permissions: sagepub.com/journalsPermissions.nav

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The authors declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

References

- Alexopoulos CV, Kakuma T, Meyers BS, Young RC, Klausner E, Clarkin J. Disability in geriatric depression. American Journal of Psychiatry. 1996;153:877–885. doi: 10.1176/ajp.153.7.877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allair SH, LaValley MP, Evans SR, O’Connor GT, Kelly-Hayes M, Meenan RF, Felson DT. Evidence for decline in disability and improved health among persons aged 55 to 70 years: The Framingham Heart Study. American Journal of Public Health. 1999;89:1678–1683. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.11.1678. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aneshensel CS, Frerichs RR, Huba GJ. Depression and physical illness: A multiwave, nonrecursive causal model. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1984;25:350–371. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA. Structural equations with latent variables. New York, NY: Wiley; 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Bollen KA, Curran PJ. Latent curve models: A structural equation perspective. New York, NY: Wiley; 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Braden JB, Zhang L, Zimmerman FJ, Sullivan MD. Employment outcomes of persons with a mental disorder and comorbid chronic pain. Psychiatric Services. 2008;59:878–885. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.59.8.878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burgard SA, Brand JE, House JS. Toward a better estimation of the effect of job loss on health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2007;48:369–384. doi: 10.1177/002214650704800403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doshi JA, Cen L, Polsky D. Depression and retirement in late middle-aged U.S. workers. Health Services Research. 2008;43:693–713. doi: 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00782.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Drentea P. Retirement and mental health. Journal of Aging and Health. 2002;14:167–194. doi: 10.1177/089826430201400201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenson KR, Rosamond WD, Cai J, Diez-Roux AV, Brancati FL. Influence of retirement on leisure-time physical activity. American Journal of Epidemiology. 2002;155:692–699. doi: 10.1093/aje/155.8.692. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fries JF, Spitz P, Kraines RG, Holman HR. Measurement of patient outcomes in arthritis. Arthritis and Rheumatism. 1980;23:137–145. doi: 10.1002/art.1780230202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gallo WT, Bradley EH, Siegel M, Kasl SV. Health effects of involuntary job loss among older workers: Findings from the Health and Retirement Survey. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2000;55B:S131–S140. doi: 10.1093/geronb/55.3.s131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gatchel RJ. Comorbidity of chronic pain and mental health disorders: The biopsychosocial perspective. American Psychologist. 2004;59:795–805. doi: 10.1037/0003-066X.59.8.795. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gayman MD, Brown RL, Cui M. Depressive symptoms and bodily pain: The role of physical disability and social stress. Stress and Health. 2011;27:52–63. doi: 10.1002/smi.1319. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gibson R. Reconceptualizing retirement for Black Americans. Gerontologist. 1987;2:691–698. doi: 10.1093/geront/27.6.691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Health and Retirement Study (HRS) Public use dataset (Grant Number NIA U01AG009740) Ann Arbor, MI: Produced and Distributed by the University of Michigan with Funding from the National Institute on Aging; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog AR, House JS, Morgan JN. Relation of work and retirement to health and well-being in older age. Psychology and Aging. 1991;6:202–211. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.6.2.202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll SE. Social and psychological resources and adaptation. Review of General Psychology. 2002;6:307–324. [Google Scholar]

- Hummer RA, Benjamins MR, Rogers RG. Racial and ethnic disparities in health and mortality. In: Anderson NS, Bulatao RA, Cohen B, editors. Critical perspectives: On racial and ethnic differences in health in late life. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2004. pp. 53–94. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Johnson JV, Hall EM. Job strain, workplace social support and cardiovascular disease: A cross sectional study of a random sample of Swedish working population. American Journal of Public Health. 1988;78:1336–1342. doi: 10.2105/ajph.78.10.1336. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Juster FT, Suzman R. An overview of the Health and Retirement Study. Journal of Human Resources. 1995;30:7–56. [Google Scholar]

- Karasek R, Theorell T. Healthy work: Stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. New York, NY: Basic Books; 1990. pp. 89–103. [Google Scholar]

- Kelley-Moore JA, Ferraro KF. A 3-D model of health decline: Disease, disability, and depression among Black and White older adults. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2005;46:376–391. doi: 10.1177/002214650504600405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, Moen P. Retirement transitions, gender, and psychological well-being: A life-course, ecological model. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:212–222. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.3.p212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim H, DeVaney S. The selection of partial or full retirement by older workers. Journal of Family and Economic Issues. 2005;26:371–394. [Google Scholar]

- Lawrence RH, Jette AM. Disentangling the disablement process. Journal of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological and Social Sciences. 1996;51B:S173–S182. doi: 10.1093/geronb/51b.4.s173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leigh WA, Huff D. African Americans and social security disability insurance. Washington, DC: Joint Center for Political and Economic Studies; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Lyness JM, King DA, Cox C, Yoediono Z, Caine ED. The importance of subsyndromal depression in older primary care patients: Prevalence and associated functional disability. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society. 1999;47:647–452. doi: 10.1111/j.1532-5415.1999.tb01584.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshall VW, Clarke PJ, Ballantyne PJ. Instability in the retirement transition–effects on health and well-being in a Canadian study. Research on Aging. 2001;23:379–409. [Google Scholar]

- McAdoo HP. Black families. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- McGarry K. Health and retirement: Do changes in health affect retirement expectations? Journal of Human Resources. 2004;39:625–648. [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd VC, Hill NE, Dodge KA. African American family life: Ecological and cultural diversity. New York, NY: Guilford Press; 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Meeks S, Murrell SA, Mehl RC. Longitudinal relationships between depressive symptoms and health in normal older and middle-aged adults. Psychology and Aging. 2000;15:100–109. doi: 10.1037//0882-7974.15.1.100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Midanik LT, Soghikian K, Tekawa IS. The effect of retirement on mental health and health behaviors: The Kaiser Permanante Retirement Study. Journals of Gerontology. 1995;50:S59–S61. doi: 10.1093/geronb/50b.1.s59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mutchler JE, Burr JA, Massagli MP, Pienta A. Work transitions and health in later life. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 1999;54B:S232–S261. doi: 10.1093/geronb/54b.5.s252. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Muthén L, Muthén B. Mplus user’s guide. 3. Los Angeles, CA: Muthén & Muthén; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Nagi SZ. An epidemiology of disability among adults in the United States. Milbank Memorial Fund Quarterly: Health and Society. 1976;54:439–467. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ormel J, Rijsdijk FV, Sullivan M, van Sonderen E, Kempen GIJM. Temporal and reciprocal relationship between IADL/ADL disability and depressive symptoms in late life. Journal of Gerontology: Psychological Sciences. 2002;57B:338–347. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.p338. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pavalko EK, Elder GH, Jr, Clipp EC. Worklives and longevity: Insights from a life course perspective. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1993;34:363–380. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pienta AM, Hayward MD. Who expects to continue working after age 62? The retirement plans of couples. Journals of Gerontology Series B-Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences. 2002;57:S199–S208. doi: 10.1093/geronb/57.4.s199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Quinn JF, Kozy M. The role of bridge jobs in the retirement transition: Gender, race, and ethnicity. Gerontologist. 1996;36:363–372. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.3.363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radloff LS. The CES-D scale: A self-report depression scale for research in the general population. Applied Psychosocial Measurement. 1977;1:385–401. [Google Scholar]

- RAND Center for the Study of Aging. RAND HRS data (Version H) Santa Monica, CA: With Funding From the National Institute on Aging and the Social Security Administration; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Reitzes D, Mutran E, Fernandez M. Does retirement hurt well-being? Factors influencing self-esteem and depression among retirees and workers. The Gerontologist. 1996;36:649–656. doi: 10.1093/geront/36.5.649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosow I, Breslau N. A Guttman Health Scale for the aged. Journal of Gerontology. 1966;21:556–559. doi: 10.1093/geronj/21.4.556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross CE, Drentea P. Consequences of retirement activities for distress and the sense of personal control. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 1998;39:317–334. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shapiro A, Yarborough-Hayes R. Retirement and older men’s health. Generations. 2008;32:49–53. [Google Scholar]

- Short PF, Weaver FM. Transitioning to Medicare before age sixty-five. Health Affairs. 2008;27:w175–w184. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.w175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Simons LA, McCallum J, Friedlander Y, Simons J. Healthy ageing is associated with reduced and delayed disability. Age and Ageing. 2000;29:143–148. doi: 10.1093/ageing/29.2.143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- van Solinge H. Health change in retirement: A longitudinal study among older workers in the Netherlands. Research on Aging. 2007;29:225–256. [Google Scholar]

- van Solinge H, Henkens K. Couples’ adjustment to retirement: A multi-actor panel study. Journal of Gerontology: Social Sciences. 2005;60B:S11–S20. doi: 10.1093/geronb/60.1.s11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sterns HL, Chang B. Workforce issues and retirement. In: Cavanaugh JC, Cavanaugh CK, editors. Aging in America: Societal issues. Vol. 3. Santa Barbara, CA: Praeger Perspectives; 2010. pp. 81–105. [Google Scholar]

- Verbrugge LM, Jette AM. The disablement process. Social Science and Medicine. 1994;38:1–14. doi: 10.1016/0277-9536(94)90294-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: Evidence and needed research. Journal of Behavioral Medicine. 2009;32:20–47. doi: 10.1007/s10865-008-9185-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams DR, Sternthal M. Understanding racial-ethnic disparities in health: Sociological contributions. Journal of Health and Social Behavior. 2010;51:S15–S27. doi: 10.1177/0022146510383838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]