Summary

BACKGROUND

ADAMTS13 proteolytic activity is controlled by the conformation of its substrate, von Willebrand factor (VWF), and changes in the secondary structure of VWF are essential for efficient cleavage. Substrate recognition is mediated through several non-catalytic domains in ADAMTS13 distant from the active site.

OBJECTIVES

We hypothesized that not all binding sites for ADAMTS13 in VWF are cryptic and analyzed binding of native VWF to ADAMTS13.

METHODS

Immunoprecipiation of VWF-ADAMTS13 complexes using anti-VWF antibodies and magnetic beads was used. Binding was assessed by western blotting and immunosorbent assays.

RESULTS

Co-immunoprecipitation demonstrated that ADAMTS13 binds to native multimeric VWF (Kd of 79 ± 11 nM) with no measurable proteolysis. Upon shear-induced unfolding of VWF, binding increased 3-fold and VWF was cleaved. Binding to native VWF was saturable, time dependent, reversible, and did not vary with ionic strength (I of 50 to 200). Moreover, results with ADAMTS13 deletion mutants indicated that binding to native VWF is mediated through domains distal to the ADAMTS13 spacer, likely thrombospondin-1 repeats. Interestingly, this interaction occurs in normal human plasma with an ADAMTS13 to VWF stoichiometry of 0.0040 ± 0.0004 (mean ± SEM, n = 10).

CONCLUSIONS

ADAMTS13 binds to circulating VWF and may therefore be incorporated into a platelet-rich thrombus, where it can immediately cleave VWF that is unfolded by fluid shear stress.

Keywords: von Willebrand factor, ADAMTS13, co-immunoprecipitation

Introduction

Von Willebrand factor (VWF) is a multimeric glycoprotein that circulates in blood and binds to subendothelium. VWF contains binding sites for both platelet receptors and subendothelial matrix proteins, so it functions to capture platelets onto injured blood vessels [1]. The growth of VWF-platelet aggregates is limited by the plasma metalloprotease ADAMTS13, which cleaves VWF multimers under conditions of high fluid shear stress [2]. ADAMTS13 is a member of the “A Disintegrin And Metalloprotease with ThromboSpondin-1 motifs” family of metalloproteases, and starting at the N-terminus it consists of a Ca2+ and Zn2+-dependent metalloprotease (M), a disintegrin-like domain (D), a thrombospondin-1 repeat (TSR, T), cysteine-rich (C) and spacer (S) domains, seven tandem TSRs, and two CUB domains [3]. Congenital or acquired deficiency of ADAMTS13 causes thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura (TTP), a frequently fatal disorder characterized by disseminated microvascular thrombosis [4].

Although ADAMTS13 is constitutively active [5] VWF is not cleaved without substantial changes in its secondary structure so to expose the cryptic cleavage site Y1605-M1606 in its A2 domain [6,7]. Proteolytic reactions in which the substrate requires activation are relatively unusual, and deciphering this phenomenon is critical for understanding the regulation of VWF proteolysis. For example, ADAMTS13 has several VWF-binding exosites that might function independently to interact with native or incompletely activated VWF. If so, then ADAMTS13-VWF complexes could occur in the circulation without causing VWF cleavage.

Binding experiments have provided mixed evidence on this point so far. For example, native VWF in solution was unable to inhibit the binding of ADAMTS13 to unfolded VWF adsorbed on a plastic surface [8]. This indicates that native VWF does not interact with all sites on ADAMTS13 that are available to unfolded VWF, but do not exclude a distinct interaction between native VWF and ADAMTS13.

A few studies support such an interaction. For example, Fujikawa et al found that ADAMTS13 and presumably native VWF can be co-purified from a commercial FVIII/VWF concentrate by size exclusion chromatography. In addition, high concentrations of VWF could shift all of the ADAMTS13 into column fractions containing VWF, which is consistent with concentration-dependent binding of ADAMTS13 to VWF [9]. Also, McKinnon et al have reported qualitatively detectable ADAMTS13 binding to immobilized but apparently native VWF [10].

We have now characterized the equilibrium binding of ADAMTS13 and truncated variants to native (i.e. folded) and unfolded VWF in solution. The results are consistent with a model involving at least two distinct interactions that depend on the conformational state of VWF. The proximal MDTCS domains of ADAMTS13 are required to recognize unfolded or sheared VWF, whereas domains distal to the spacer domain contribute to the recognition of native VWF. Interestingly, ADAMTS13 can bind native VWF without cleaving it. ADAMTS13-VWF complexes can be detected in normal human plasma (NHP), suggesting that some ADAMTS13 is already bound to VWF before incorporation into a thrombus.

Methods

Recombinant ADAMTS13 expression and purification

Human recombinant ADAMTS13 (rADAMTS13) proteins with C-terminal 6xHis and V5 epitope tags were expressed using the inducible T-REx system (Invitrogen, Carslbad, CA) as previously reported [11]. Conditioned media were diluted with two volumes of 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, and applied to a column of Q Sepharose FF (GE Healthcare, Waukesha, WI). After washing with the same buffer, bound rADAMTS13 was eluted with 25 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, containing 1 M NaCl. Pooled fractions were concentrated by ultrafiltration (Centriprep, Millipore, Billerica, MA), exchanged into 50 mM MES, pH 6.6, in desalting columns (Zeba, Thermo scientific, Waltham, MA), and adsorbed on Heparin Sepharose (GE Healthcare). After washing with 50 mM MES, pH 6.6, containing 25 mM NaCl, rADAMTS13 was eluted with 50 mM MES, pH 6.6, containing 1 M NaCl. Fractions were pooled, concentrated by ultrafiltration and dialyzed against 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2 and 150 mM NaCl.

ADAMTS13-VWF binding assays

Binding reactions (20 μL total volume) were prepared in 0.2 mL PCR tubes (MicroAmp, Applied Biosystems, Inc.) and typically contained 30 μg mL−1 VWF substrate (120 nM of VWF monomers), 30 nM rADAMTS13, 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 150 mM NaCl and 1 mg mL−1 bovine serum albumin (Sigma Aldrich, St Louis, MO). VWF was either purified recombinant VWF [12] (rVWF, provided by Dr. Peter Turecek, Baxter Innovations, Vienna, Austria) or purified plasma VWF (pVWF, Haematologic Technologies Inc., Essex Junction, VT). When used, fluid shear stress was applied to reactions essentially as described [13]. Briefly, reactions were incubated at room temperature on a bench-top vortex device (Vortex-Genie 2, Scientific Industries, Inc., Bohemia, NY) at maximal speed (3,200 rpm) for 200 seconds.

Binding reactions were incubated for 10 min with 30 μL magnetic beads (Dynabeads Protein G, Invitrogen) coupled according to the manufacturer’s directions to a mixture of monoclonal anti-VWF CK domain IgG1κ antibodies 11–29, 62-12, and 38-08. These antibodies were raised by standard methods (Green Mountain Antibodies, Burlington, VT) against recombinant VWF CK domains [14] and do not affect the cleavage of VWF by ADAMTS13 (data not shown). The magnetic beads were separated from the supernatant fraction and washed three times with 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.5% (v/v) Tween 20. Time-dependent dissociation of ADAMTS13-VWF complexes was slow compared to the time of washing (5 minutes).

Analysis of binding and activity

For Kd measurements, bound proteins were eluted with 19.2 μL 50 mM glycine, pH 2.5, followed by immediate neutralization with 0.8 μL 2 M Tris base (80 mM final concentration). Eluted ADAMTS13 antigen then was measured by ELISA with monoclonal antibody 20A5 (anti-TSR8) to immobilize, biotin-labeled 5C11 (anti-TSR2) to detect, and NHP (n=20) as a standard, containing approximately 1 μg mL−1 (6 nM) enzyme [15,16]. Eluted VWF antigen (VWF:Ag) was measured by ELISA [17]. Under these conditions, 30 μL of beads repeatedly precipitated about 1.9 pmol of VWF. Control experiments demonstrated that exposure of VWF or ADAMTS13 to the low pH conditions of elution from Dynabeads® had no effect on detection in their respective ELISAs, and had no effect on behavior in binding assays (data not shown). The apparent dissociation constant Kd for rADAMTS13 was determined by non-linear least-squares fitting to the one-site quadratic binding equation (Prism, GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA). Stoichiometry of binding was determined from the molar ratio of ADAMTS13 to VWF, each determined by ELISA.

For analysis of binding, proteins were eluted with 20 μL electrophoresis sample buffer (62.5 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.0, 1% (m/v) sodium dodecyl sulphate (SDS), 10% glycerol). If reducing conditions were required, 25 mM dithiothreitol was added to the electrophoresis sample buffer. Proteins were electrophoresed on 4% to 12% Bis-Tris gradient NuPage® gels and transferred to polyvinyldifluoride membranes (Invitrogen), which were then blocked with 0.5% casein in Tris buffered saline (TBS), pH 7.4. Recombinant ADAMTS13 was detected with Alexa Fluor 647-conjugated mouse anti-V5 antibody for fluorescent imaging and with HRP-anti-V5 for chemiluminescent imaging (Invitrogen). Plasma-derived ADAMTS13 was detected with monoclonal antibody 17B10 (anti-TSR3) and peroxidase labeled goat anti-mouse IgG (Jackson Immunoresearch, West Grove, PA). VWF was detected with a mixture of three anti-A1 monoclonal antibodies RG46, 52K-2, [18] and 52K-8 [19] with epitopes in the VWF A1 domain (provided by Dr. Zaverio Ruggeri, La Jolla, CA) and Alexa Fluor 633-conjugated goat anti-mouse IgG (Invitrogen) or peroxidase labeled polyclonal rabbit anti-VWF (Dako Cytomation, Glostrup, Denmark). Band intensities were quantitated on a Typhoon Trio scanner with ImageQuant TL software (GE Healthcare).

To analyze enzyme activity following immunoprecipitation, beads were added to a 2.0 μM FRETS-VWF73 (Peptides International, Louiville, KY) substrate solution in 50 mM HEPES, pH 7.4, 5 mM CaCl2, 1 μM ZnCl2, 150 mM NaCl. Generation of product was analyzed by measuring fluorescence every 5 min using the same settings as reported previously [11]. Initial velocities expressed as ΔF/t were used as a measure for the enzymatic activity present in the immunoprecipitate, with ΔF = F(t) – F(0). Prior to the assay, beads were precipitated on a 96-well magnet to minimize scattering of the generated signal.

VWF multimer analysis

VWF multimers were separated by SDS agarose gel electrophoresis essentially as described [20,21]. Samples were applied on a 1.5% (m/v) IEF agarose (GE Healthcare) gel fixed on a GelBondTM carrier (Cambrex Bio Science Rockland Inc., Rockland, ME). VWF was detected using anti-VWF immunoglobulins (Dako Cytomation) labeled with alkaline phosphatase and the AP conjugate substrate kit (BioRad, Hercules, CA).

Results

ADAMTS13 binds to native VWF

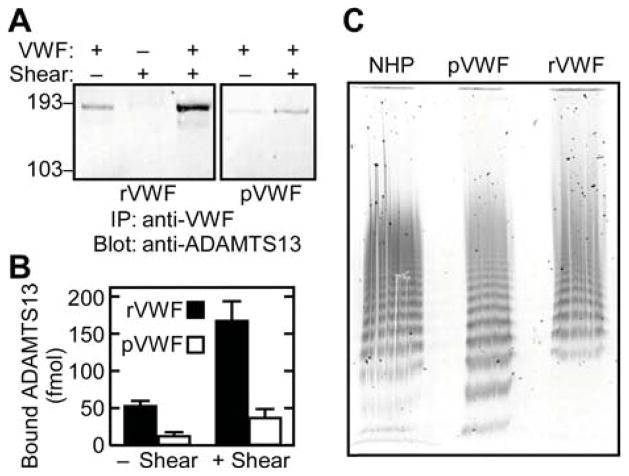

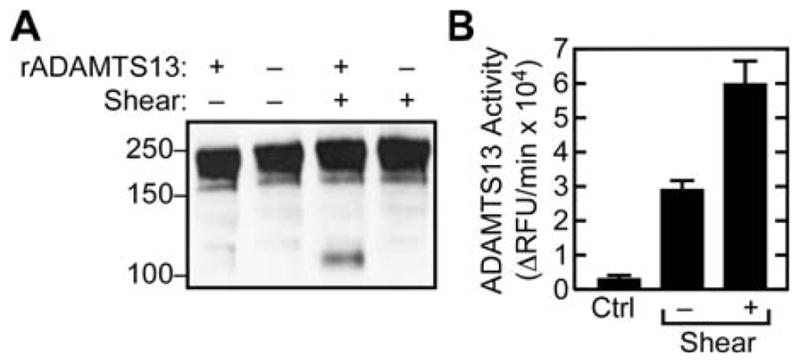

ADAMTS13 requires substantial conformational changes in the substrate to cleave VWF and uses several exosites to recognize VWF, which suggests that some ADAMTS13 exosites might bind to motifs that are accessible on native VWF. In fact, when purified rADAMTS13 (30 nM) and rVWF (30 μg mL−1) were mixed and immunoprecipitated with anti-VWF antibody, a significant amount of rADAMTS13 was pulled down (Fig. 1A). Recombinant ADAMTS13 also bound to plasma derived VWF (pVWF) albeit significantly less (Figs. 1A and 1B). Multimer analysis showed small differences between rVWF and purified pVWF (Fig 1C). Compared to VWF multimers in NHP, rVWF had slightly larger multimers and pVWF had slightly smaller multimers. In particular, pVWF and NHP contained significant amounts of dimers and tetramers that were absent in rVWF. Both pVWF and rVWF had similar collagen binding activity, with a VWF:CBA/VWF:Ag ratio of 0.6 (n = 2) compared to 1.0 for a NHP standard. As expected, VWF was not cleaved detectably in the absence of shear stress (Fig. 2A) although the co-immunoprecipitated rADAMTS13 was active, as shown by cleavage of FRETS-VWF73 substrate [22] (Fig. 2B). Thus, active rADAMTS13 can bind native VWF without cleaving it.

Figure 1. rADAMTS13 binds to native multimeric VWF.

(A) Solutions containing VWF (30 μg mL−1) and rADAMTS13 (30 nM), with or without fluid shear stress as indicated, and immunoprecipitated with anti-VWF. rADAMTS13 was analyzed by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with AlexaFluor647-conjugated anti-V5 anti-body and fluorescence imaging. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. (B) Fluorescent signals for rADAMTS13 were quantified, compared to an internal rADAMTS13 standard and expressed in fmol. Error bars display the SEM (n=9). (C) Samples of normal human plasma (NHP) (3 μL), pVWF (30 ng) and rVWF (30 ng) were analyzed by SDS-agarose gel electrophoresis and in-gel staining with phosphatase labeled anti-VWF.

Figure 2. Activity of rADAMTS13.

(A) VWF was incubated with or without rADAMTS13 (30 nM), with or without fluid shear stress, and analyzed for VWF cleavage by SDS-PAGE under reducing conditions and Western blotting with anti-VWF monoclonal antibodies recognizing the A1 domain and therefore specific for the N-terminal VWF cleavage product. Molecular weight markers are indicated on the left. (B) Following immunprecipitation, washed beads were incubated with the fluorogenic substrate FRETS-VWF73. Product generation is expressed as the change in relative fluorescence units (ΔRFU) per minute. The control condition (Ctrl) lacked VWF and indicates non-specific interaction of rADAMTS13 with beads. Error bars display the SEM (n=3).

Fluid shear stress increases rADAMTS13 binding

To assess changes in enzyme-substrate complex formation as a consequence of VWF unfolding, mixtures of rADAMTS13 and VWF were exposed briefly to high fluid shear stress. Subsequent immunoprecipitation with anti-VWF showed that rADAMTS13 binding was increased approximately three-fold (Fig. 1). In addition, application of shear stress resulted in significant proteolysis of VWF, as shown by the detection of a 140 kDa N-terminal cleavage product by SDS-PAGE (with reduction) and Western blotting (Fig. 2A). In control conditions lacking VWF, no rADAMTS13 was co-immunoprecipitated (Fig. 1A). Binding was not strongly dependent on ionic strength, yielding the same signal in the absence or presence of 150 mM NaCl (data not shown).

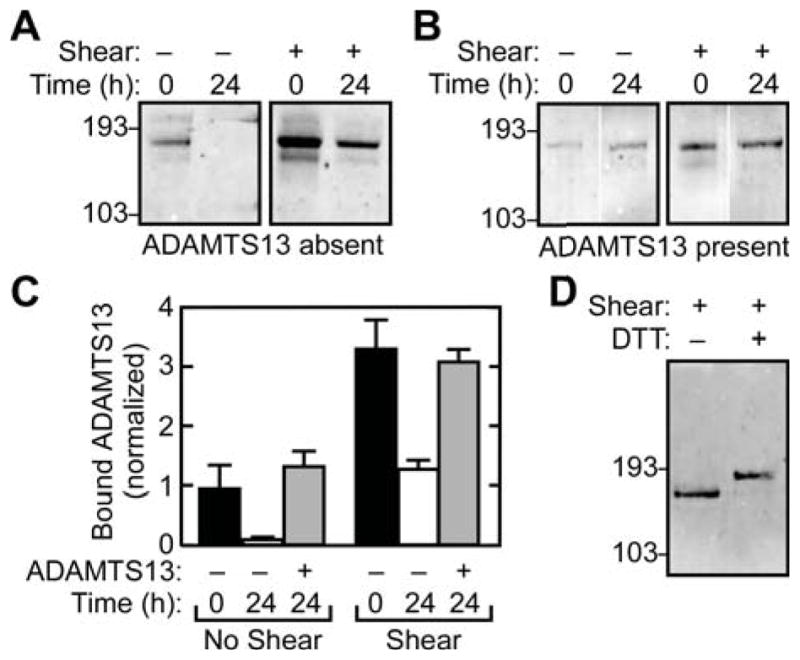

Binding is reversible and noncovalent

To illustrate reversibility, binding reactions containing VWF and rADAMTS13 were immunoprecipitated with anti-VWF, washed, incubated in buffer for 24 h, and analyzed for residual bound rADAMTS13 by Western blotting (Figs 3A and 3C). Over this time course, rADAMTS13 almost completely dissociated from native VWF. The majority of rADAMTS13 bound to sheared VWF also dissociated (Figs 3A and 3C).

Figure 3. Binding is reversible and detergent sensitive.

Solutions of rADAMTS13 (30 nM) and rVWF (30 μg mL−1), with or without shear stress, were immunoprecipitated with anti-VWF. The beads were resuspended in buffer containing no rADAMTS13 (A) or 30 nM rADAMTS13 (B). Bound rADAMTS13 was then analyzed immediately (0 h) or after 24 h by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-V5. (C) Signals for rADAMTS13 and VWF were quantified by fluorescence scanning and the amount of bound rADAMTS13 was normalized to the rADAMTS13/rVWF value obtained for binding at time = 0 h to unsheared VWF (first lane, panel A). Error bars display the SEM (n=3). (D) Samples of rADAMTS13 bound to rVWF with shear stress were immunoprecipitated with anti-VWF and analyzed by SDS-PAGE with or without 10 mM dithiothreitol, followed by Western blotting and detection of rADAMTS13 with anti-V5 antibody. Results are representative of at least three independent experiments.

Shear forces may influence VWF stability and promote disulfide bond formation or rearrangement [23,24]. It is possible that disulfide mediated enzyme-substrate complexes are formed under these conditions, since an unpaired cysteine residue is predicted to be present at the C-terminus of the first CUB domain of human ADAMTS13 [3]. However, analysis of co-immunoprecipitated rADAMTS13 under reducing and non-reducing conditions yielded indistinguishable signals (Fig. 3D), indicating that little or no rADAMT13 was sequestered in disulfide-linked complexes with VWF. In addition, no immunoreactivity for rADAMTS13 was detected under non-reducing conditions at positions larger than 193 kDa, which excludes the occurrence of covalent rADAMTS13-VWF complexes. Therefore the increased binding established during exposure to fluid shear stress is noncovalent.

VWF relaxation does not interfere with rADAMTS13 binding

At physiologically relevant levels of fluid shear stress, VWF multimers undergo reversible transitions from a globular to an extended conformation [25]. The relationship of these transformations to binding or cleavage by ADAMTS13 has not been reported. In another study, high levels of fluid shear stress were shown to induce a marked increase in susceptibility to proteolytic cleavage that appeared to be irreversible [7]. Shear stress also induces rADAMTS13 binding to VWF [13] but the stability of this change in VWF behavior has not been described. To address this question, samples of VWF and rADAMTS13 were sheared and analyzed by coimmunoprecipitation immediately or 24 h after cessation of shear stress. Interestingly, rADAMTS13 binding did not significantly change over this interval (Figs. 3B and 3C). Consequently, the rADAMTS13 binding interaction is reversible upon removal of excess free ligand (Figs. 3A and 3C) but the increased shear-induced binding in the presence of free ligand can not be reversed by cessation of shear stress (Figs. 3B and 3C).

Stoichiometry and affinity

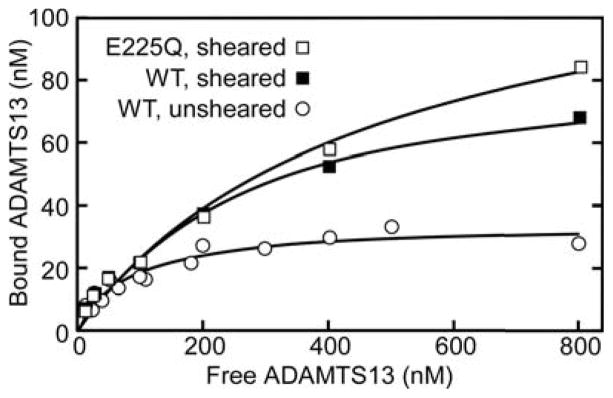

To control for the possibility that proteolysis could perturb VWF structure and binding properties, we performed detailed binding studies with mutant rADAMTS13E225Q in addition to wild type. The former construct has a single amino acid mutation at the essential active site Glu residue and is inactive against FRETS-VWF73 or denatured multimeric VWF (data not shown). Binding to unsheared VWF was measured after immunoprecipitation by ELISA, and the data are consistent with a single class of binding sites based on the high quality of the fit to the one-site binding equation. rADAMTS13E225Q has an apparent dissociation constant (Kd) of 79 ± 11 nM and a stoichiometry at saturation of 0.23 ± 0.01 (SEM, n = 3) (Fig. 4). Wild type rADAMTS13 bound to unsheared VWF with similar affinity and stoichiometry, as expected (data not shown). This result suggests that approximately one-fourth of the VWF subunits in a native multimer has functional binding sites for ADAMTS13. In contrast, ADAMTS13 bound to sheared VWF with lower affinity (Kd >500 nM) and higher stoichiometry (Fig. 4), suggesting that shear stress exposed a new class of binding sites. Interestingly, wild type rADAMTS13 and rADAMTS13E225Q gave similar binding curves, indicating that substrate cleavage has little effect on enzyme binding (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. Binding stoichiometry and affinity.

(A) Solutions of rVWF (120 nM) and varying concentrations of rADAMTS13E225Q were incubated without shear stress and immunoprecipitated with anti-VWF. Concentrations of bound rADAMTS13 and rVWF were determined by ELISA. The results were fitted to a one-site quadratic binding equation by non-linear regression. (B) A similar binding experiment was performed with rVWF and wild-type rADAMTS13 (WT) or rADAMTS13E225Q (E225Q) subjected to shear stress. Under these conditions, binding was not saturated at 800 nM rADAMTS13.

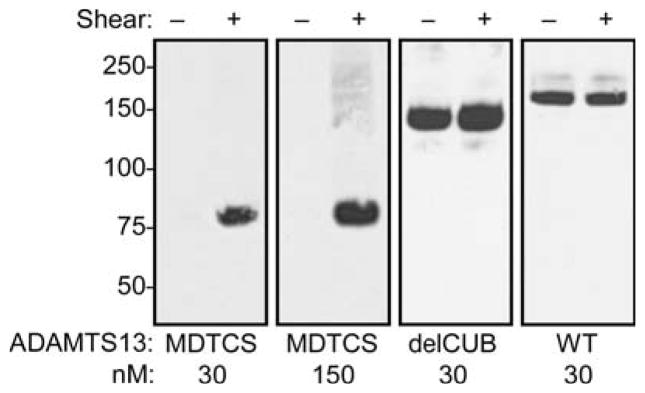

Binding without shear depends on distal TSR domains of ADAMTS13

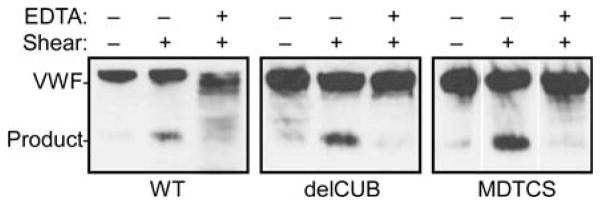

Zhang et al demonstrated that a rADAMTS13 mutant lacking domains C-terminal from the spacer (MDTCS) is inactive under conditions of mechanical shear stress. We questioned if the binding of truncated constructs MDTCS and delCUB (truncated after the eighth TSR) would also be hampered. The binding of delCUB was not different than WT (Fig. 5), and rADAMTS13 delCUB bound to VWF with a Kd of 100 ± 30 nM (SEM, n = 3). In contrast, no interaction between MDTCS and native rVWF could be detected (Fig. 5). Even at high concentrations of MDTCS (150 nM), no detectable binding took place in the absence of shear stress. These data indicate that TSR domains located between the spacer and the CUB domains are important for binding to native VWF. However, when shear stress was applied, WT ADAMTS13, delCUB and MDTCS constructs all bound to VWF similarly (Fig. 5) and cleaved pVWF (Fig. 6) or rVWF (not shown). Equal amounts of truncated rADAMTS13 variants cleaved 2.0 μM FRETS-VWF73 at equal rates (not shown).

Figure 5. Binding of truncated rADAMTS13 mutants.

Solutions of rVWF (30 μg mL−1) and the indicated rADAMTS13 variants, with or without shear stress, were immunoprecipitated with anti-VWF antibodies and bound rADAMTS13 detected by SDS-PAGE and Western blotting with anti-V5 antibody. Blots were visualized by chemiluminescence and exposure to X-ray film.

Figure 6. rADAMTS13 truncated variants cleave VWF treated with fluid shear stress.

Solutions of pVWF (30 μg mL−1) and 30 nM of wild-type rADAMTS13 (WT), rADAMTS13 truncated after TSR8 (delCUB), or rADAMTS13 truncated after the spacer domain (MDTCS) were incubated as indicated with or without 10 mM EDTA, with or without shear stress. Samples were analyzed by SDS-PAGE with reduction and Western blotting with monoclonal anti-VWF antibodies against VWF A1 domain. The results are representative for three independent experiments.

ADAMTS13-VWF complex formation in plasma

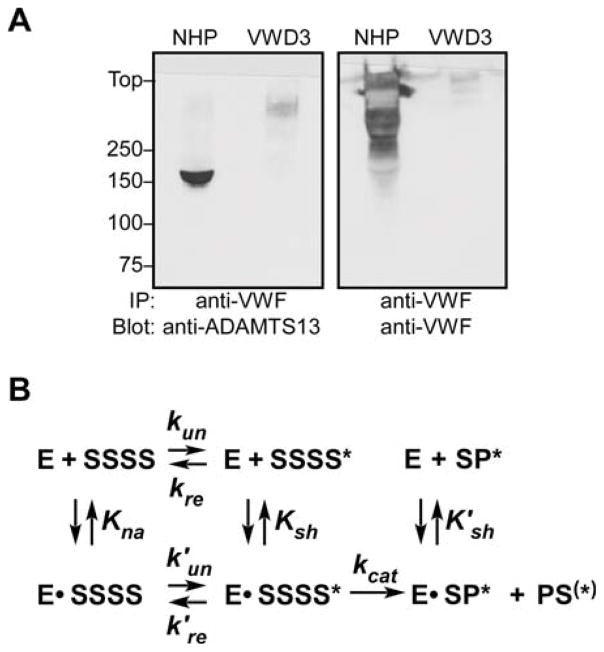

To assess whether enzyme-substrate binding occurs in plasma, VWF was immunoprecipitated from unsheared NHP and analyzed by Western blotting with anti-ADAMTS13 mAb 17B10. Significant amounts of endogenous ADAMTS13 were detected (Fig. 7A), indicating that some ADAMTS13 molecules are complexed with VWF in the circulation. As a control for specificity, no ADAMTS13 was co-immunoprecipitated from VWD type 3 plasma, which contained normal ADAMTS13 activity as determined by FRETS-VWF73 assay (data not shown). The stoichiometry of ADAMTS13-VWF binding in NHP was determined by ELISA to be 0.0040 ± 0.0004 (mean ± SEM, n=10) or approximately one ADAMTS13 molecule per 250 VWF monomers. Therefore, approximately 3 percent of circulating ADAMTS13 may be bound to endogenous VWF in plasma.

Figure 7. ADAMTS13-VWF complexes are present in plasma.

(A) Samples of normal human plasma (NHP) or VWD type 3 plasma (VWD3) were immunoprecipitated with anti-VWF. Bound proteins were analyzed by SDS-PAGE under nonreducing conditions and Western blotting with monoclonal antibody 17B10, which recognizes ADAMTS13 domain TSR3 (left), or polyclonal anti-human VWF (right). (B) A model for ADAMTS13-VWF interactions and the effects of fluid shear stress. ADAMTS13 (E) binds to subunits (S) of native multimeric VWF (SSSS) with a dissociation constant of Kna. This interaction requires distal ADAMTS13 TSR domains and does not lead to product generation. Fluid shear stress alters the conformation of some subunits (S*), which then bind ADAMTS13 with a dissociation constant Ksh and can be cleaved at a rate of kcat. The rates of shear-induced unfolding (kun, k′un) and refolding (kre, k′re) may depend on whether ADAMTS13 is bound. ADAMTS13 can bind reversibly to products (SP*, PS(*)) with a dissociation constant of K′sh, which may differ from Ksh. The multimeric VWF products can participate in further ADAMTS13-VWF interactions.

Discussion

The unfolded A2 domain presents several binding sites that interact with exosites on ADAMTS13 distal to the metalloprotease domain and facilitate attack on the Tyr1605-Met1606 peptide bond, [8,26–28] which is buried in the central β-sheet of the native structure. [29] Experiments on enzyme-substrate binding indicate that many of these ADAMTS13 binding sites are also buried in native VWF. [8] However, one of the first reported purifications of ADAMTS13 described co-elution of the enzyme and multimeric VWF upon size exclusion chromatography, suggesting some form of interaction between the native proteins. [9]

Our data show that ADAMTS13 indeed is able to bind native rVWF in solution with an apparent Kd of 79 ± 11 nM. This value is similar to the reported Kd of 90 ± 10 nM for binding of ADAMTS13 to antibody-immobilized VWF, [10] or the Kd of 50 to 80 nM for the binding of VWF to immobilized ADAMTS13 [13]. A difference in the extent of binding was observed between rVWF and pVWF but is probably not attributable to differences in multimer distribution as this differs only marginally. Variation in glycosylation [10] and/or conformation due to a history in circulation (pVWF) or not (rVWF) could potentially contribute to the observed difference. Alternatively, other proteins copurified with plasma VWF might affect ADAMTS13 binding [30]. As anticipated, no cleavage was detected in the absence of shear stress indicating that the scissile bond is unavailable in soluble native VWF. Therefore, the observed ‘baseline’ binding (not involving substrate turnover) must differ in part from the contacts required for VWF proteolysis.

The interaction of VWF with rADAMTS13 increased substantially following the application of shear force and, as expected, [13] the VWF multimers were also proteolyzed. The increase in binding is partly explained by the exposure of new binding sites as VWF unfolds. We previously showed that plastic-immobilized VWF binds ADAMTS13 with a Kd of 14 ± 1.2 nM, or a six-fold reduction compared to binding with native VWF in solution, and a stoichiometry of approximately one ADAMTS13 molecule per two VWF subunits [8]. Surface immobilization appears to evoke conformational changes in VWF analogous to those induced by fluid shear stress, increasing the number of binding sites and/or affinity for ADAMTS13. [31]

The difference in affinity implies that the binding sites are structurally different, and our results indicate that distinct ADAMTS13 domains mediate binding to sheared and native VWF. ADAMTS13 binding to sheared VWF requires the ADAMTS13 MDTCS domains, whereas binding to native VWF requires ADAMTS13 TSR repeats distal to the spacer domain. The corresponding ADAMTS13 binding sites on native VWF have not been identified, but it seems likely that domains C-terminal of VWF domain A2 mediate binding to distal TSR repeats of ADAMTS13.

Our results concerning the role of ADAMTS13 in recognizing VWF are similar to those of Zhang and colleagues, [13] with a few differences. In both studies, distal TSR repeats of ADAMTS13 were needed to bind VWF. However, we observed that full length and delCUB variants of ADAMTS13 bound similarly to native VWF (Fig. 5), whereas Zhang and colleagues found that delCUB bound 5 to 7-fold less tightly. [13] We observed that full length, delCUB and MDTCS recombinant variants of ADAMTS13 cleaved VWF comparably under conditions of high fluid shear stress (Fig. 6), whereas Zhang and colleagues reported that constructs delCUB and MDTCS had little or no activity under these conditions. [13] These different results may reflect differences in assay conditions and methods of product detection. However, the major conclusions are consistent: distal ADAMTS13 domains are required for significant binding to native VWF.

Interestingly, the inactive mutant rADAMTS13E225Q and wild type rADAMTS13 bound similarly to both native and sheared VWF. These results indicate that increased ADAMTS13 binding to sheared VWF is not explained by high affinity product binding to the enzyme [27] because substrate cleavage is not necessary for binding.

Furthermore, ADAMTS13 binding to either native or sheared VWF is reversible upon removal of excess free ligand. Yet, the high capacity binding state induced in VWF by shear stress is not reversible by simply stopping shear stress application, at least not over the time course studied. Some VWF conformational changes induced by shear stress are rapidly reversible, allowing elongated multimers to return to a globular state when shear forces decrease. [25] However, this globular-to-stretched transition probably is distinct from the unfolding of individual VWF A2 domains, which is likely to require more force and may be reversible over a longer time course. [32] Although single A2 domains clearly can unfold and refold reversibly [32], refolding of A2 domains within VWF multimers may be inhibited by interactions with other VWF domains. Also, ADAMTS13 binding to sheared VWF may involve sites outside of the A2 domain. In addition, binding of ADAMTS13 may stabilize the unfolded state of the A2 domain and prevent refolding. Whether ADAMTS13 also stabilizes the elongated conformation of VWF multimers is unknown.

Our observations and others [28] suggest a model in which substrate unfolding regulates enzyme binding affinity as well as proteolysis (Fig. 7B). Native VWF binds to distal ADAMTS13 TSR repeats with relatively low affinity (Kna) and without cleavage. The A2 domains within the VWF multimer unfold and refold with rate constants (kun, kre) that depend on the magnitude of fluid shear stress; binding of ADAMTS13 may influence these rates (k′un, k′re). Through its MDTCS domains, ADAMTS13 binds more tightly to sheared (unfolded) VWF A2 domains [8] (Ksh) and may subsequently cleave them (kcat). ADAMTS13 also binds to the products of cleavage. [25] Based on studies with model peptide substrates [26,28] the dissociation constants for binding sheared VWF (Ksh) and product (K′sh) may be comparable.

Approximately 3 percent of the ADAMTS13 in NHP is bound to endogenous VWF (Fig. 7A), suggesting that ADAMTS13-VWF complexes may be incorporated into a growing platelet-rich thrombus. This amount of ADAMTS13 is likely to be functionally significant, because shear stress increases binding only 3-fold (Fig. 1B), which is nevertheless sufficient to regulate VWF function. The fraction of ADAMTS13 bound to circulating VWF might be increased further in patients with conditions that cause pathologically increased fluid shear stress, such as stenotic heart valves or arteries narrowed by atherosclerosis. This process may facilitate the feedback inhibition of thrombus growth, bypassing a requirement for ADAMTS13 to penetrate dense thrombi by diffusion from the blood lumen. Such a mechanism is consistent with studies of a naturally occurring truncated ADAMTS13 variant in mice (Adamts13s) that lacks two C-terminal TSR repeats and both CUB domains. Homozygous Adamts13s/s mice have a thrombogenic phenotype, with accelerated thrombus growth in arterioles injured with ferric chloride. [33] The truncated Adamts13s/s also has essentially normal activity toward small peptide substrates but markedly reduced ability to cleave VWF multimers [34] or to inhibit platelet deposition at high fluid shear rates in vitro. [33] The selectively decreased activity of truncated ADAMTS13 toward VWF multimers, in vitro and in vivo, indicates that distal ADAMTS13 domains are required for normal hemostasis. Whether the physiological function of distal ADAMTS13 domains depends on binding to VWF remains to be established.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr. Peter L. Turecek (Baxter Innovations, Vienna, Austria) for recombinant VWF, and Dr. Zaverio M. Ruggeri (Scripps Research Institute, La Jolla, CA) for monoclonal antibodies against human VWF. H.B.F. and K.V. are fellows of the Research Foundation-Flanders (Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek-Vlaanderen). H.B.F. was also supported by the US commission for educational exchange (Fulbright). This work was supported in part by National Institute of Heath (Bethesda, MD) grants HL72917 and HL89746 (J.E.S.), by American Heart Association (Dallas, TX) National Scientist Development Award 0530110N (P.J.A.), and by American Heart Association Fellow to Faculty Transition Award 0475035N (E.M.M.).

References

- 1.Sadler JE. Biochemistry and genetics of von Willebrand factor. Annu Rev Biochem. 1998;67:395–424. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.67.1.395. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tsai HM. Current concepts in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. Annu Rev Med. 2006;57:419–436. doi: 10.1146/annurev.med.57.061804.084505. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng X, Chung D, Takayama TK, Majerus EM, Sadler JE, Fujikawa K. Structure of von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease (ADAMTS13), a metalloprotease involved in thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura. J Biol Chem. 2001;276:41059–41063. doi: 10.1074/jbc.C100515200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadler JE. A new name in thrombosis, ADAMTS13. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2002;99:11552–11554. doi: 10.1073/pnas.192448999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Majerus EM, Zheng XL, Tuley EA, Sadler JE. Cleavage of the ADAMTS13 propeptide is not required for protease activity. J Biol Chem. 2003;278:46643–46648. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M309872200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Furlan M, Robles R, Lammle B. Partial purification and characterization of a protease from human plasma cleaving von Willebrand factor to fragments produced by in vivo proteolysis. Blood. 1996;87:4223–4234. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tsai HM. Physiologic cleavage of von Willebrand factor by a plasma protease is dependent on its conformation and requires calcium ion. Blood. 1996;87:4235–4244. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Majerus EM, Anderson PJ, Sadler JE. Binding of ADAMTS13 to von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:21773–21778. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M502529200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fujikawa K, Suzuki H, McMullen B, Chung D. Purification of human von Willebrand factor-cleaving protease and its identification as a new member of the metalloproteinase family. Blood. 2001;98:1662–1666. doi: 10.1182/blood.v98.6.1662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.McKinnon TAJ, Chion ACK, Millington AJ, Lane DA, Laffan MA. N-linked glycosylation of VWF modulates its interaction with ADAMTS13. Blood. 2008;111:3042–3049. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-06-095042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Anderson PJ, Kokame K, Sadler JE. Zinc and calcium ions cooperatively modulate ADAMTS13 activity. J Biol Chem. 2006;281:850–857. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M504540200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Varadi K, Rottensteiner H, Vejda S, Weber A, Muchitsch EM, Turecek PL, Ehrlich HJ, Schwarz HP. Species-dependent variability of ADAMTS13-mediated proteolysis of human recombinant von Willebrand factor. J Thromb Haemost. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2009.03453.x. Prepublished on April 24, 2009 as. 10 1111/j 1538-7836 2009 03453×. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang P, Pan WL, Rux AH, Sachais BS, Zheng XL. The cooperative activity between the carboxyl-terminal TSP1 repeats and the CUB domains of ADAMTS13 is crucial for recognition of von Willebrand factor under flow. Blood. 2007;110:1887–1894. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-04-083329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Katsumi A, Tuley EA, Bodo I, Sadler JE. Localization of disulfide bonds in the cystine knot domain of human von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem. 2000;275:25585–25594. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M002654200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Feys HB, Canciani MT, Peyvandi F, Deckmyn H, Vanhoorelbeke K, Mannucci PM. ADAMTS13 activity to antigen ratio in physiological and pathological conditions associated with an increased risk of thrombosis. Br J Haematol. 2007;138:534–540. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2007.06688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feys HB, Liu F, Dong N, Pareyn I, Vauterin S, Vandeputte N, Noppe W, Ruan C, Deckmyn H, Vanhoorelbeke K. ADAMTS-13 plasma level determination uncovers antigen absence in acquired thrombotic thrombocytopenic purpura and ethnic differences. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:955–962. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.01833.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Tuley EA, Gaucher C, Jorieux S, Worrall NK, Sadler JE, Mazurier C. Expression of von Willebrand factor “Normandy”: an autosomal mutation that mimics hemophilia A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:6377–6381. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Mohri H, Fujimura Y, Shima M, Yoshioka A, Houghten RA, Ruggeri ZM, Zimmerman TS. Structure of the von Willebrand factor domain interacting with glycoprotein Ib. J Biol Chem. 1988;263:17901–17904. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Fujimura Y, Usami Y, Titani K, Niinomi K, Nishio K, Takase T, Yoshioka A, Fukui H. Studies on anti-von Willebrand factor (vWf) monoclonal antibody NMC-4, which inhibits both ristocetin-induced and botrocetin-induced vWf binding to platelet glycoprotein Ib. Blood. 1991;77:113–120. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.De Meyer SF, Vandeputte N, Pareyn I, Petrus I, Lenting PJ, Chuah MKL, VandenDriessche T, Deckmyn H, Vanhoorelbeke K. Restoration of plasma von Willebrand factor deficiency is sufficient to correct thrombus formation after gene therapy for severe von Willebrand disease. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2008;28:1621–1626. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.108.168369. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ruggeri ZM, Zimmerman TS. The complex multimeric composition of factor VIII/von Willebrand factor. Blood. 1981;57:1140–1143. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kokame K, Nobe Y, Kokubo Y, Okayama A, Miyata T. FRETS-VWF73, a first fluorogenic substrate for ADAMTS13 assay. Br J Haematol. 2005;129:93–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2005.05420.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Choi H, Aboulfatova K, Pownall HJ, Cook R, Dong JF. Shear-induced disulfide bond formation regulates adhesion activity of von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35604–35611. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M704047200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Li Y, Choi H, Zhou Z, Nolasco L, Pownall HJ, Voorberg J, Moake JL, Dong JF. Covalent regulation of ULVWF string formation and elongation on endothelial cells under flow conditions. J Thromb Haemost. 2008;6:1135–1143. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2008.02991.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schneider SW, Nuschele S, Wixforth A, Gorzelanny C, Alexander-Katz A, Netz RR, Schneider MF. Shear-induced unfolding triggers adhesion of von Willebrand factor fibers. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:7899–7903. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0608422104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gao WQ, Anderson PJ, Sadler JE. Extensive contacts between ADAMTS13 exosites and von Willebrand factor domain A2 contribute to substrate specificity. Blood. 2008;112:1713–1719. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-04-148759. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao WQ, Anderson PJ, Majerus EM, Tuley EA, Sadler JE. Exosite interactions contribute to tension-induced cleavage of von Willebrand factor by the antithrombotic ADAMTS13 metalloprotease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:19099–19104. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0607264104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wu JJ, Fujikawa K, McMullen BA, Chung DW. Characterization of a core binding site for ADAMTS-13 in the A2 domain of von Willebrand factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2006;103:18470–18474. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609190103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhang Q, Zhou YF, Zhang CZ, Zhang X, Lu C, Springer TA. Structural specializations of A2, a force-sensing domain in the ultralarge vascular protein von Willebrand factor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2009;106:9226–9231. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0903679106. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cao WJ, Krishnaswamy S, Camire RM, Lenting PJ, Zheng XL. Factor VIII accelerates proteolytic cleavage of von Willebrand factor by ADAMTS13. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 2008;105:7416–7421. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0801735105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Raghavachari M, Tsai HM, Kottke-Marchant K, Marchant RE. Surface dependent structures of von Willebrand factor observed by AFM under aqueous conditions. Colloids Surf B Biointerfaces. 2000;19:315–324. doi: 10.1016/s0927-7765(00)00140-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Zhang X, Halvorsen K, Zhang CZ, Wong WP, Springer TA. Mechanoenzymatic cleavage of the ultralarge vascular protein von Willebrand factor. Science. 2009;324:1330–1334. doi: 10.1126/science.1170905. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banno F, Chauhan AK, Kokame K, Yang J, Miyata S, Wagner DD, Miyata T. The distal carboxyl-terminal domains of ADAMTS13 are required for regulation of in vivo thrombus formation. Blood. 2009;113:5323–5329. doi: 10.1182/blood-2008-07-169359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zhou W, Bouhassira EE, Tsai HM. An IAP retrotransposon in the mouse ADAMTS13 gene creates ADAMTS13 variant proteins that are less effective in cleaving von Willebrand factor multimers. Blood. 2007;110:886–893. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-01-070953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]