Abstract

Background

von Willebrand disease Vicenza is characterized by low plasma VWF levels, the presence of ultra-large (UL) VWF multimers and less prominent satellite bands on multimer gels, and the heterozygous amino acid substitution R1205H in the VWF gene. The pathogenesis of VWD Vicenza has been elusive. Accelerated clearance is implicated as a cause of low VWF level.

Objectives

We addressed the question, whether the presence of ultra-large multimers is a cause, or a result of accelerated VWF clearance, or whether it is an unrelated phenomenon.

Patients/Methods

We studied the detailed phenotype of three Hungarian patients with VWD Vicenza, expressed the mutant VWF-R1205H in 293T cells, and developed a mathematical model to simulate VWF synthesis and catabolism.

Results

We found that the half life of VWF after DDAVP was approximately one tenth of that after the administration of Haemate P, a source of exogenous wild type VWF (0.81±0.2 vs. 7.25±2.38 hours). An analysis of recombinant mutant VWF-R1205H showed that the biosynthesis and multimer structure of WT and mutant VWF were indistinguishable. A mathematical model of the complex interplay of VWF synthesis, clearance and cleavage showed that decreasing VWF half life to one tenth of normal reproduced all features of VWD Vicenza including low VWF level, ultra-large multimers and a decrease of satellite band intensity.

Conclusion

We conclude that accelerated clearance alone may explain all features of VWD Vicenza.

Keywords: von Willebrand disease, von Willebrand factor, Clearance

Introduction

VWD Vicenza was originally described in 1988 in the Italian province Vicenza[1], followed by reports of families from Germany[2], Turkey[2], and Hungary[3]. This variant is classified as type 1 VWD[4]. VWD Vicenza is characterized by highly penetrant autosomal dominant inheritance, low plasma and normal platelet VWF levels, proportional decrease of VWF antigen and activity, and the presence of ultra-large VWF multimers (ULVWF)[1] in the plasma of some individuals. Some authors note less prominent satellite bands on multimer gels[5]. This peculiar phenotype has been linked to the heterozygous amino acid substitution R1205H [6].

The pathogenesis of VWD Vicenza has been elusive since its description. A recent report described shortened survival of freshly secreted VWF after administration of DDAVP[5], but this study has been criticized for using individuals with normal plasma VWF concentration as controls instead of other type 1 patients with similarly reduced baseline levels[7]. Indeed, two type 1 patients with the C1130F mutation seemed to have rapid VWF clearance similar to that of patients with the Vicenza phenotype[7]. Comparisons of plasma VWF half lives between only a few individuals are especially difficult, because normal VWF levels are known to have a broad range, reflecting wide variations in production and/or clearance. The problem is compounded by the complex course of the response to DDAVP and the need to sample many time points to determine the VWF half life accurately. Finally, although increased clearance could account for the low VWF levels observed among VWD Vicenza patients, it remained unclear whether the presence of ULVWF multimers is a cause, a result, or an unrelated phenomenon[5]. Likewise, the subtle change in satellite band pattern was left unexplained. Two hypotheses have been advanced to explain ULVWF multimers. Impaired constitutive secretion was presumed to result in the multimer profile of these patients which is reminiscent of the ULVWF multimers observed in platelets or immediately after the release of VWF stored in Weibel-Palade bodies[6]. Alternatively, the mutant subunits were proposed to have a propensity for ectopic multimerization in the ER, which could explain both the shift in multimer distribution towards unusually large molecules and, in analogy to some highly penetrant type 1 VWD variants, cause low VWF levels by intracellular retention of mutant-containing multimers[3].

In order to address these problems, we studied two Hungarian families with VWD Vicenza, in which we compared the rate of decline in VWF levels after DDAVP to that after the administration of Haemate P, a source of exogenous wild type (WT) VWF. Since there is no known method to dissect constitutive and regulated secretion in vivo, we set out to test the hypothesis of ectopic multimer formation by analyzing recombinant mutant VWF-R1205H containing the R1205H mutation in exon 27. Finally, to elucidate the effect of VWF survival on multimeric structure, we developed a mathematical model of VWF secretion and catabolism. Our findings confirm that VWF survival is indeed shortened in patients with VWD Vicenza, and indicate that ectopic multimerization does not play a role in the phenotype. Mathematical modeling strongly suggests that increased clearance alone can explain the combination of low VWF levels and the presence of ultra-large multimers as well as less apparent satellite bands in VWD Vicenza.

Patients and methods

Patients

Two families with VWD Vicenza were identified during a study of families with highly penetrant VWD and very low levels of VWF in Hungary[3]. In both families, the entire VWF gene was sequenced. All participating patients signed an informed consent and the institutional ethical committee approved the current study.

DDAVP was administered at a dose of 0.3 μg/kg intravenously, in a 15-minute infusion. All patients who received Haemate P in this study had received Haemate P during bleeding episodes previously. Haemate P was administered in a dose of 60 IU/kg (given as units for VWF:RCof).

Ivy bleeding time

Standard procedure was used utilizing a standardized 1 mm incision on the ventral surface of the forearm during venous stasis provided by a blood pressure cuff inflated to 40 mm Hg. Blood was gently removed with a filter paper every 30 seconds. The timer was stopped the first time when no fresh blood was seen on the filter paper.

Expression of recombinant VWF

293T human kidney cells[8] or COS-7 monkey kidney cells were transiently transfected in 6-well plates with pSVHVWF1, or pSVHR1205H, using a calcium phosphate method [9] and culture conditions described previously[10]. Cells were washed in phosphate-buffered saline 24 hours after transfection and grown an additional 48 hours in 1 mL serum-free medium (Opti-MEM I, Life Technologies, Gaithersburg, MD). Some of the expression experiments were performed in the presence of monensin (Sigma, St. Louis, MO), a cationic ionophore that inhibits Golgi functions. Conditioned media and cell lysates (0.5 mL) were collected as described[11]. The lysis buffer contained 0.6% Triton X-100, 10 μg/mL aprotinin (Sigma, St Louis, MO), and 100 μg/mL phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (Sigma) in 0.1 M Tris-HCl, pH 8.0.

Protein gel electrophoresis and VWF:Ag immunoassay

Analysis of recombinant VWF multimers was performed by sodium dodecyl sulfate (SDS)-agarose (1.5 %) gel electrophoresis and Western blotting as previously described[12]. VWF multimers were visualized with rabbit polyclonal horseradish peroxidase-labeled antihuman VWF antibody P0226 (Dako, Denmark) and the ECL chemiluminescence system (Amersham Pharmacia Biotech).

Recombinant VWF antigen concentrations were measured by an enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) method[13] using rabbit polyclonal antihuman VWF antibody 082 and rabbit polyclonal horseradish peroxidase-labeled antihuman VWF antibody P226 (Dako).

Ristocetin cofactor activity, collagen binding and FVIII measurements

Ristocetin cofactor activity (VWF:RCof) was measured in a standard fashion, using the slope of the time-curve of ristocetin-induced platelet agglutination. Lyophilized platelets, ristocetin and calibration standards were all purchased from Helena, Gateshead, UK. Collagen binding activity (VWF:CB) was determined in an ELISA system. Briefly, ELISA microplates were coated with 5 μg/ml human placental collagen (Sigma) in PBS for 48 hour at 4 °C. After a blocking step with 1% BSA and appropriate washing, human citrated plasma samples were tested against a standard curve in 1:100 and 1:200 dilutions in two parallel dilutions each. Samples were incubated for two hours at room temperature. After washing, bound VWF was detected with a HRP-peroxidase labelled rabbit-anti-human VWF (Dako). FVIII levels were detected with a CA 1500 coagulometer using a standard protocol with FVIII-deficient plasma (Behring).

Mathematical model

Details of the mathematical model are reported separately[14]. Briefly, the model simulates secretion, cleavage and clearance of circulating VWF molecules. Secretion is assumed to occur at a constant rate, or is increased acutely after DDAVP. Secreted multimers are assumed to have two conformations, “open” or “closed”. Only “open” VWF molecules may undergo cleavage, with a probability of pclv (see below). The probability of “open” conformation (pop) increases with increasing multimer size, and the association is described by the opening function. Above a certain multimer size (ultra large, i.e. multimers containing ≥ Nop subunits), all multimers are always in the “open” conformation (pop=1). All simulations in this paper were performed with two opening functions: f(n)=kop*n3 and f(n)=kop*1.05n, (where the factor kop is optimized to match patient or normal plasma multimer patterns). Basically similar results were obtained with both functions. However, for the sake of simplicity, and because the exponential function resulted in gel patterns slightly more similar to the VWF multimer gels of patients, only results with f(n)=kop*1.05n are shown.

Clearance is assumed to be independent of multimer size [15], and occurs with a time constant Rclr. T1/2 is determined in simulated DDAVP tests by acutely increasing the rate of production approximately 30 times for 35 minutes in a way similar to clinical practice. Clearance kinetics also follows the Michaelis Menten equation. EC50 is the plasma VWF concentration at which the clearance mechanism is half saturated. EC50 was arbitrarily set at 400 % of normal steady-state VWF level, because our data (not shown in this paper) suggest second order clearance kinetics for VWF[16].

To visualize the simulations, the GelWizard module of the program software transforms numeric data into gel patterns [14].

Results

Identification of the causative mutation in two highly penetrant type 1 VWD families

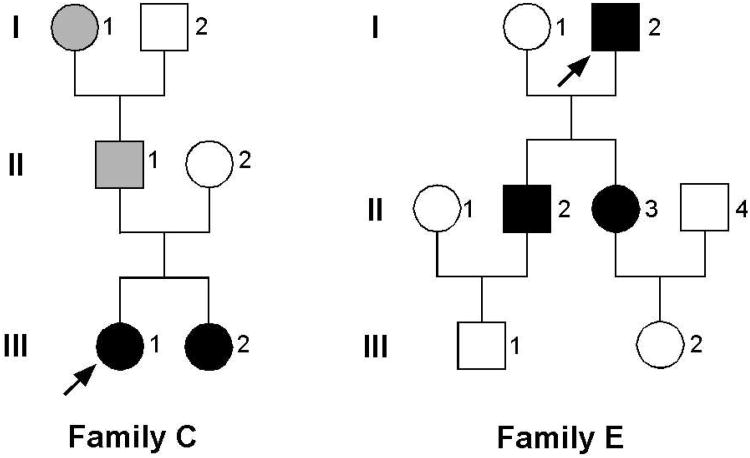

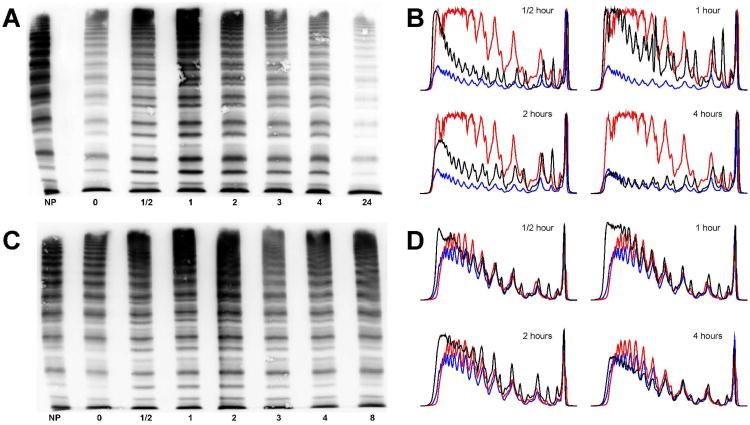

These families were recruited to a study designed to identify the cause of severe type 1 VWD with high penetrance. The entire coding region was sequenced from the selected 5 families. In two families, R1205H mutation was found in exon 27 with no other candidate mutations identified. A second substitution, M740I, described in some but not all families with VWD Vicenza[17], was not found in either of the Hungarian patients. Family trees, laboratory and clinical characteristics are shown in Figure 1 and Table 1. Multimer patterns of a VWD Vicenza patient before and after the administration of DDAVP are compared to a normal control in Figure 2. As seen in the figure, patient E-II-3 has low levels of VWF with a relatively high proportion of ULVWF. Also, satellite bands, representing proteolytic fragments, are faint. After the administration of DDAVP, however, these satellite bands become transiently prominent, but are again faint in the steady-state reached beyond 4 hours.

Figure 1. Family trees of two VWD-Vicenza families.

Affected family members are shown in black. Family members with a history of bleeding, but no laboratory data are marked in grey. The proposita is marked with an arrow.

Table 1. Clinical and laboratory† details of members of the two Vicenza families.

| Family member | ABO | VWF:Ag (%) | VWF:RCo (%) | VWF:CB (%) | FVIII (%) | aPTT (sec) | Ivy (min) | Multimer‡ | PFA* | Bleeding |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C-III-1 | 0 | 17 | <10 | ND | 9 | 34.7 | 12 | UL | ND | N-E-T |

| C-III-2 | 0 | 8 | <10 | ND | ND | ND | 14.5 | UL | Abnorm | none |

| E-I-2 | A | 14 | <10 | 6.8 | 12 | 48 | 12 | UL | Abnorm | N-G-B-GI |

| E-II-2 | 0 | 6 | <10 | 8.5 | 17 | 45.8 | 20 | UL | Abnorm | N-B |

| E-II-3 | A | 16 | <10 | 8 | 20 | 49.6 | 15 | UL | Abnorm | N-M-P |

| E-III-1 | 0 | 83 | 64 | ND | 148 | 37.5 | ND | Norm | ND | N-B |

| E-III-2 | 0 | 116 | 122 | ND | 206 | 41.2 | ND | Norm | ND | none |

N=nosebleed; E=post-extraction bleed; T=post-tonsillectomy bleed; G=gum bleed; M=menorrhagia; B=easy bruising; GI= GI bleed; P=post-partum bleed (bold face type= major bleeding).

Normal ranges are as follows: VWF:Ag: 50-150; VWF:RCo: 50-150; VWF:CB: 50-150; FVIII: 50-150; aPTT: 25-35; Ivy bleeding time: <10 min.

UL – Ultra-large multimers present

Cartridges for PFA-100 Collagen/epinephrine and Collagen/ADP were used with congruous results.

Figure 2. Multimer patterns before and after DDAVP in a patient with VWD Vicenza.

Panels A and C show multimeric structures of patient E-II-3 and a normal control, respectively. Densitometric analysis of the multimer gels shown in Panel A (Panel B) and of the gels in Panel C (Panel D) at time points 0, ½, 1, 2, and 4 hours. The densitometric tracing of patient (or control) time point 0 is shown in blue, while the normal plasma control is red for comparison. NP: Normal plasma. Numbers under each gel indicate time points in hours.

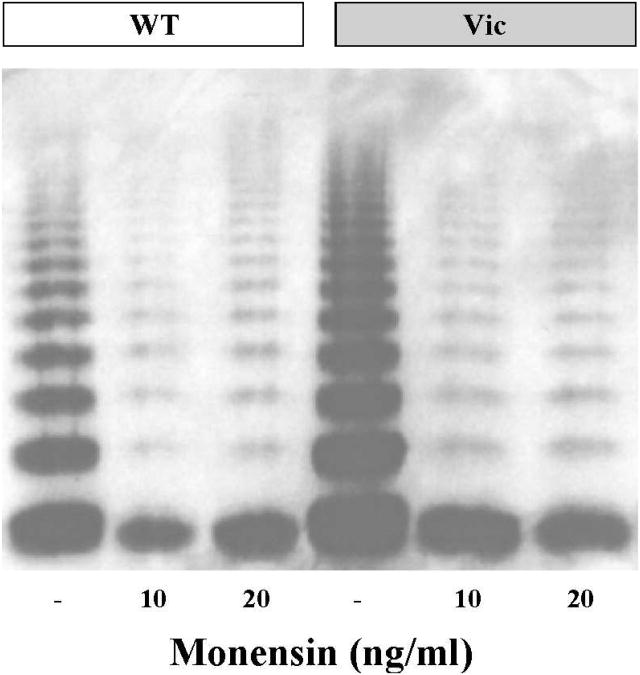

Synthesis and multimeric structure of hrVWF-R1205H is identical to hrVWF-WT

To study the impact of R1205H on the synthesis of VWF, we expressed rVWF-WT and rVWF-R1205H in 293T cells. In addition, we addressed the question of whether rVWF-R1205H has an increased ability to form multimers in the cells by inhibiting Golgi functions using the cationic ionophore monensin[21]. As determined by ELISA in transfected 293T cell supernatants, mutant and VWF-WT were produced at comparable rates (data not shown), and the addition of monensin had a similar inhibitory effect on the multimerization and secretion of both mutant and VWF-WT. (Figure 3) Therefore, ectopic multimer formation in the ER as the main mechanism for the Vicenza phenotype seems highly unlikely.

Figure 3. Multimer structure of WT and R1205H rVWF produced by 293T cells.

Multimeric patterns and production rates of WT and mutant cells are indistinguishable under baseline conditions, or after the addition of monensin, an ionophore that disrupts Golgi function and prevents multimer assembly in the Golgi.

Clearance of endogenous (R1205H) VWF is increased compared to exogenous (WT) VWF in patients with VWD Vicenza

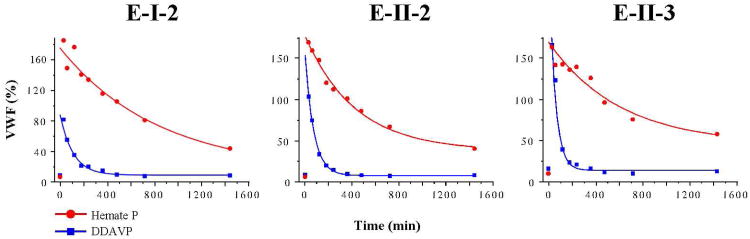

Three Vicenza patients from family E were administered DDAVP in standard dose (0.3 μg/kg) in a 15-min infusion. Blood samples were drawn at the following time points: 0, 30 60 minutes and 2, 3, 4, 6, 8 12 and 24 hours. Haemate P (HP) was administered after a washout period of at least two weeks in a dose of 25 U/kg (Units given for FVIII:C). VWF:Ag levels decreased with a half life of (mean ± SD): 0.72±0.12 and 5.93±2.28 hours after DDAVP and HP, respectively (Figure 4). The difference was statistically significant. Mean VWF:Ag half life was approximately 9 times shorter in Vicenza patients for endogenous VWF than for exogenous VWF-WT, which, in turn, was similar to VWF half life calculated for normal controls (n=5) after DDAVP (Table 2). The changes in multimer pattern after the administration of DDAVP are depicted in Figure 2. In addition to normal controls, we tested two additional patients with known molecular VWF defects; A-II-1 with heterozygous C1130Y severe type 1, and B-III-2 with heterozygous R1597Q type 2A VWD. VWF-C1130 half life was decreased to a quarter of VWF-WT (T1/2 being 1.2 and 4.79 hours for DDAVP and Haemate P, respectively), while R1597Q half life was similar to VWF-WT (4.33 and 5.3 hours) in these patients (Table 2). Similar results were obtained for VWF:RCo and FVIII (data not shown) with the exception of VWF:RCo for R1597Q, which was significantly shortened (0.78 vs. 3.18 hours). This is in line with the known increased susceptibility to cleavage in VWD type 2A patients. The two patients from Vicenza family C declined to participate in the DDAVP/Haemate P part of the study.

Figure 4. Clearance of R1205H-VWF is increased in patients with VWD Vicenza.

DDAVP and Haemate P was administered to patients, at least two weeks apart. VWF levels were measured at 0, 0.5, 1, 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, 12, and 24 hours. Endogenous VWF-R1205H is cleared from the plasma much faster than exogenous VWF-WT contained in transfused Haemate P.

Table 2. Clearance of VWF:Ag in various subtypes of VWD.

| Family | Member | Mutation | T1/2-DDAVP (hours) | T1/2-HP (hours) | VWF:Ag Baseline (%) | VWF:Ag Peak* (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E | I-2 | R1205H | 0.99 | 9.71 | 10 | 97 |

| E | II-2 | R1205H | 0.84 | 4.96 | 8 | 103 |

| E | II-3 | R1205H | 0.59 | 7.09 | 16 | 165 |

| Mean±SD | 0.81±0.2 | 7.25±2.38 | 11.3±4.2 | 121.7±37.7 | ||

| A | II-1 | C1130Y | 1.20 | 4.79 | 12 | 27 |

| B | III-2 | R1597Q | 4.33 | 5.3 | 84 | 198 |

| Control (n = 5) | – | 5.59±2.22 | N/A | 70±21 | 181±33 |

The highest VWF Ag concentration measured after DDAVP administration.

In a mathematical model, increased clearance alone reproduces the multimer pattern of VWD Vicenza patients

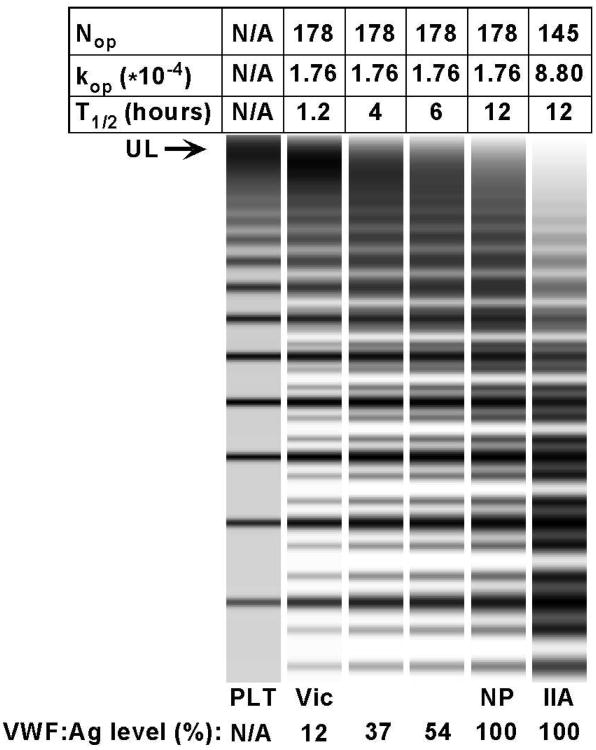

In our simulations, the following parameters were empirically found to produce a multimer pattern closely resembling that of normal plasma: kop1.76*10-4(corresponding to Nop = 178); pclv: 0.06, Km: 9e13; T1/2: 12 h, EC50: 400 %. These values were also chosen to match the VWF half life described in the literature. The same experiments were repeated with changing only one parameter at a time (Figure 5). Decreasing the half life by a factor of ten: from the normal 12 hours to 1.2 (a change of similar magnitude to what we observed in our patients) reproduced the VWD Vicenza multimer pattern. This increase in clearance resulted in a steady-state VWF level of 12%, also a typical value for VWD Vicenza patients. Conversely, when we increased kop by a factor of five (corresponding to a decrease of Nop from 178 to 145), we observed a typical VWD type 2A multimer pattern (Figure 5).

Figure 5. Simulation of VWF production and catabolism under five different conditions.

Normal plasma has a half life of 12 hours, and a Nop/kop of 178/1.76*10-4. If half life is decreased by a factor of ten, a typical Vicenza multimer pattern is produced. Decreasing the half life to a lesser degree (to half or a third) results in VWF:Ag levels of 54 and 37 %, respectively, but the upward shift in multimers is much less apparent. Conversely, when kop is increased by a factor of 5 (corresponding to a decrease of Nop from 178 to 145), a typical 2A (variant IIA) pattern is produced.

Discussion

In this paper we explore the mechanism by which the heterozygous amino acid substitution R1205H results in the Vicenza phenotype: low levels of plasma VWF, normal platelet VWF and the presence of ultra large multimers in plasma. First we showed that the biosynthesis of recombinant rVWF-R1205H is identical to VWF-WT. Furthermore, multimer assembly of mutant and VWF-WT is equally sensitive to monensin, a Golgi inhibitor. In addition, the cell lysates contained no detectable multimers (data not shown). Taken together, these findings make it very unlikely that ectopic multimer formation in the ER should be responsible for the presence of unusually large multimers, as was hypothesized before[3]. In looking for another mechanism, we confirmed and extended Casonato and coworkers' observation[5] that the plasma survival of VWF is reduced in patients with VWD Vicenza. In particular, this study was criticized for using individuals with normal VWF concentration as controls instead of other type 1 patients with similarly reduced baseline levels of VWF[7]. Therefore we chose to compare the clearance of mutant and VWF-WT in the very same patients: endogenous VWF clearance was compared to clearance of Haemate P, which contains VWF-WT. Clearly, VWF-R1205H has a half life approximately one order of magnitude shorter than VWF-WT in the same patients. We also point out that the measurement of VWF clearance is technically difficult. Even a small laboratory error in one of the time points may result in a relatively large deviation of the estimated half life. Therefore, for accurate comparisons, it is essential to use a DDAVP (or Haemate P) curve with as many points as feasible. To this end, we designed a curve with ten points, which helped to decrease the internal imprecision of clearance estimation. Taken together, our data unequivocally show in humans that VWF-R1205H is cleared an order of magnitude more rapidly than VWF-WT. This result is consistent with a report that human VWF-R1205H has shortened intravascular survival in rodents[18].

Although the large increase in clearance rate explains the low VWF level in these patients, it was not clear whether the presence of ULVWF multimers is a cause, a result, or an unrelated epiphenomenon in VWD Vicenza[7]. Mathematical modeling provides some insight into this question. For example, decreasing the half life of VWF will cause a shift toward ULVWF multimers even if no other parameter is changed. One has to be careful interpreting the behavior of any complex model that has several parameters to consider. For this reason, we used an extensive validation process to ascertain that simulations correspond to measurable biological processes[14]. When its parameters were optimized to matched published data and our independent results on VWF survival, the model generated the expected multimer patterns at steady state and during DDAVP trials. In the case of VWD Vicenza, changing the clearance rate alone reproduced the observed ULVWF pattern, resting plasma VWF level, and time course of VWF clearance after DDAVP. In addition, the clearance of transfused wild type VWF (Haemate P) was normal in patients with VWD Vicenza. Therefore, the observed shift towards ULVWF multimers appears to be explained solely by increased clearance. This result also makes intuitive sense, because shortening the time during which newly secreted VWF is exposed to ADAMTS13 cleavage will cause a shift towards the initial ULVWF multimer distribution that is secreted from endothelial cells.

In addition, modeling predicts that the VWF multimer satellite bands, which reflect subunit proteolysis, should be somewhat less apparent in patients with VWD Vicenza. In fact, decreased satellite bands have been reported previously in VWD Vicenza[5] and we have observed this as well (Figure 2). When numeric calculations were made, compared to a normal control, the satellite/main band ratio for dimers was decreased by 20 % in patient E-II-3, and by 38 % in the mathematical model for Vicenza conditions (data not shown). This phenomenon is a logical consequence of the rapid clearance of VWF-R1205H, which results in a decreased opportunity for proteolytic cleavage. It should be kept in mind that the effects discussed of accelerated clearance on VWF proteolysis apply to the steady state only. After the DDAVP-triggered release of stored VWF, ULVWF will be exposed to the same cleavage as normal VWF, until steady state is reached again (see early time points, Figure 2).

Some patients with the R1205H mutation have not shown ULVWF multimers even when a very sensitive multimer technique was used. The reason for this variation in the relationship between genotype and phenotype is currently unknown. To our knowledge, information about the precise half life of plasma VWF in the patients with normal multimers is not available. Although it is clear that R1205H decreases VWF half life in all patients in whom it has been determined, VWF clearance may have other determinants (e.g. variations in the currently unknown clearance receptor), and mathematical modeling suggests that a small increase in half life is sufficient to shift the multimer distribution towards normal. When the plasma VWF half life is varied between 1.2 hours (VWD Vicenza) and 12 hours (normal), a very narrow “multimer transition zone” is observed in which the predicted multimer pattern shifts from ULVWF to normal. A very short half life of 1.2 hours produced ULVWF multimers, whereas an intermediate half life of 4 to 6 hours produced patterns that were difficult to distinguish from normal (Figure 5). In addition, the multimer size may also have other determinants (such as ADAMTS13 level). These factors may account for the variation in plasma VWF multimer distribution observed among patients with the VWF-R1205H mutation.

VWF-R1205H is not the only subtype of VWD in which shortened survival has been observed. Patients with the mutation C1130F [7] or C1149R[19] had a VWF:Ag half-life of 1.5 h, and patients with the mutations W1144G and S2179F in the D3 and D4 domains, respectively, had VWF:Ag half-lives of 1-3.6 h [23, 24]. Other patients with VWD type 1 have also been described with increased VWF clearance after DDAVP, using the VWF propeptide to VWF antigen ratio[20, 21] or the VWF decline after a DDAVP response[22], and the VWF:Ag half-life appears to correlate with the baseline VWF level[23, 24].The question is logical: why don't these patients have ULVWF multimers? We cannot exclude the possibility that some mutations produce a normal multimer distribution through several counterbalancing effects on VWF biology. For example, a mutation might increase clearance and also interfere with multimer assembly, resulting in the net effect of a nearly normal multimer pattern. However, as discussed in the previous paragraph, mathematical modeling suggests another explanation for at least some of these mutations. The relatively modest decrease in half life associated with these mutations may simply not be sufficient to shift the multimer distribution to ULVWF. The narrow multimer transition zone is a feature inherent in the exponential dependence of cleavage on VWF multimer length. Therefore, VWF clearance may increase over a wide range producing decreased VWF plasma levels, before it reaches an extreme value that will also produce a noticeable shift in multimer distribution. Real-life plasma VWF multimer gels will be even less able to identify the subtle shifts in multimer distribution than are these simulated gels.

The mechanism of VWF clearance is currently uncharacterized. It is likely to take place in the liver[18], presumably mediated by a receptor on macrophage-like cells[25] that has not been identified. The R1205H mutation results in a gain of function, and we hypothesize that VWF-R1205H binds to a clearance receptor with increased avidity. From this viewpoint, it is noteworthy that all mutations reported to cause increased clearance have been found in the D3 and D4 domains.

A single patient has so far been described with the VWD Vicenza phenotype but no mutation in the VWF gene[26]. Haemate P was also rapidly cleared in this patient. Based on analogy with the VWF-GPIb interaction, and the relationship between VWD type 2B and pseudo-VWD, this variant could be called pseudo-Vicenza VWD or pseudo-VWD type 1C[20]. Such a phenotype might be caused by a gain-of-function mutation in a VWF clearance receptor in the liver.

The therapeutic implication of finding a short VWF survival after DDAVP is unclear, and awaits future studies. Pending more information, we adopted a policy to administer DDAVP every 4 hours to these patients prior to and during surgery, with good results in the few instances. Obviously, proper precautions need to be taken to insure the maintenance of fluid and electrolyte balance, and, the safety and efficacy of this approach needs to be proven by a properly designed study. When such an approach is unsatisfactory, these patients may require factor replacement.

In summary, we have demonstrated that VWF-R1205H is cleared rapidly from plasma with a half life approximately one-tenth that of transfused wild type VWF in the same patients. Mathematical modeling provides a conceptual framework to understand this behavior, reproducing the multimer patterns and VWF levels at steady state or after DDAVP infusions in healthy controls and in all VWD variants tested so far. In particular, decreasing the VWF half life to one tenth of normal reproduced the features of VWD Vicenza including low VWF levels, the presence of ULVWF, and reduced intensity of satellite bands. The interplay between alterations in synthesis, clearance and proteolysis lends support to a dynamic view of VWD pathogenesis.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are deeply indebted to Elodee Tuley for her invaluable technical assistance, and to Gábor Balázsi for his insightful help in developing the mathematical model.

This work was supported in part by National Institutes of Health grant HL72917 (J.E.S.), and the Hungarian National Scientific Research Foundation grant OTKA T-047340 (I.D.)

Footnotes

Contribution: A.G. designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, U.B. performed research, and contributed vital analytical tools, I.D. analyzed and interpreted data, E.N., A.M. performed some of the research, analyzed and interpreted data, A.S., Z.B. contributed vital new reagents, T.M. analyzed and interpreted data, J.E.S. designed research, analyzed and interpreted data, and I.B. designed and performed research, analyzed and interpreted data, contributed vital new reagents or analytical tools, and wrote the manuscript.

Conflict-of-interest disclosure: J.E.S. is a consultant for Baxter BioSciences.

References

- 1.Mannucci PM, Lombardi R, Castaman G, Dent JA, Lattuada A, Rodeghiero F, Zimmerman TS. von Willebrand disease “Vicenza” with larger-than-normal (supranormal) von Willebrand factor multimers. Blood. 1988;71:65–70. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zieger B, Budde U, Jessat U, Zimmermann R, Simon M, Katzel R, Sutor AH. New families with von Willebrand disease type 2M (Vicenza) Thrombosis Research. 1997;87:57–64. doi: 10.1016/s0049-3848(97)00104-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bodó I, Katsumi A, Tuley E, Schlammadinger Á, Boda Z, Sadler JE. Mutations causing dominant type 1 von Willebrand disease with high penetrance. Blood. 1999;94:373a. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sadler JE, Budde U, Eikenboom JC, Favaloro EJ, Hill FG, Holmberg L, Ingerslev J, Lee CA, Lillicrap D, Mannucci PM, Mazurier C, Meyer D, Nichols WL, Nishino M, Peake IR, Rodeghiero F, Schneppenheim R, Ruggeri ZM, Srivastava A, Montgomery RR, Federici AB. Update on the pathophysiology and classification of von Willebrand disease: a report of the Subcommittee on von Willebrand Factor. J Thromb Haemost. 2006;4:2103–14. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2006.02146.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Casonato A, Pontara E, Sartorello F, Cattini MG, Sartori MT, Padrini R, Girolami A. Reduced von Willebrand factor survival in type Vicenza von Willebrand disease. Blood. 2002;99:180–4. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.1.180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Schneppenheim R, Federici AB, Budde U, Castaman G, Drewke E, Krey S, Mannucci PM, Riesen G, Rodeghiero F, Zieger B, Zimmermann R. Von Willebrand Disease type 2M “Vicenza” in Italian and German patients: identification of the first candidate mutation (G3864A; R1205H) in 8 families. Thromb Haemost. 2000;83:136–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Castaman G, Rodeghiero F, Mannucci PM. The elusive pathogenesis of von Willebrand disease Vicenza. Blood. 2002;99:4243–4. doi: 10.1182/blood.v99.11.4243. author reply 4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.DuBridge RB, Tang P, Hsia HC, Leong PM, Miller JH, Calos MP. Analysis of mutation in human cells by using an Epstein-Barr virus shuttle system. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:379–87. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.1.379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen C, Okayama H. High-efficiency transformation of mammalian cells by plasmid DNA. Mol Cell Biol. 1987;7:2745–52. doi: 10.1128/mcb.7.8.2745. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Matsushita T, Sadler JE. Identification of amino acid residues essential for von Willebrand factor binding to platelet glycoprotein Ib. Charged-to-alanine scanning mutagenesis of the A1 domain of human von Willebrand factor. J Biol Chem. 1995;270:13406–14. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.22.13406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lyons SE, Bruck ME, Bowie EJ, Ginsburg D. Impaired intracellular transport produced by a subset of type IIA von Willebrand disease mutations. J Biol Chem. 1992;267:4424–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Raines G, Aumann H, Sykes S, Street A. Multimeric analysis of von Willebrand factor by molecular sieving electrophoresis in sodium dodecyl sulphate agarose gel. Thromb Res. 1990;60:201–12. doi: 10.1016/0049-3848(90)90181-b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tuley EA, Gaucher C, Jorieux S, Worrall NK, Sadler JE, Mazurier C. Expression of von Willebrand factor “Normandy”: an autosomal mutation that mimics hemophilia A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1991;88:6377–81. doi: 10.1073/pnas.88.14.6377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Gézsi A, Budde U, Deák I, Nagy E, Mohl A, Schlammadinger Á, Boda Z, Masszi T, Sadler JE, Bodó I. VWFWizard – A Software Program Simulating VWF Multimer Assembly, Secretion, Cleavage and Clearance. J Thromb Haemost. 2009 doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2010.03753.x. Submitted. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lenting PJ, Westein E, Terraube V, Ribba AS, Huizinga EG, Meyer D, de Groot PG, Denis CV. An experimental model to study the in vivo survival of von Willebrand factor. Basic aspects and application to the R1205H mutation. J Biol Chem. 2004;279:12102–9. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gézsi A, Mohl A, Sallai K, Nagy E, Szabó T, Sadler JE, Bodó I. Modeling VWF catabolism predicts the multimer pattern and subunit degradation in VWD Vicenza, type 1, type 2A, and healthy controls after DDAVP infusion. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:P1476. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Castaman G, Missiaglia E, Federici AB, Schneppenheim R, Rodeghiero F. An additional unique candidate mutation (G2470A; M740I) in the original families with von Willebrand disease type 2 M Vicenza and the G3864A (R1205H) mutation. Thromb Haemost. 2000;84:350–1. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lenting PJ, Westein E, Terraube V, Ribba AS, Huizinga EG, Meyer D, De Groot PG, Denis CV. An experimental model to study the in vivo survival of Von Willebrand Factor: basic aspects and application to the Arg1205His mutation. J Biol Chem. 2003;12 doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310436200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Schooten CJ, Tjernberg P, Westein E, Terraube V, Castaman G, Mourik JA, Hollestelle MJ, Vos HL, Bertina RM, Berg HM, Eikenboom JC, Lenting PJ, Denis CV. Cysteine-mutations in von Willebrand factor associated with increased clearance. J Thromb Haemost. 2005;3:2228–37. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2005.01571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Haberichter SL, Balistreri M, Christopherson P, Morateck P, Gavazova S, Bellissimo DB, Manco-Johnson MJ, Gill JC, Montgomery RR. Assay of the von Willebrand factor (VWF) propeptide to identify patients with type 1 von Willebrand disease with decreased VWF survival. Blood. 2006;108:3344–51. doi: 10.1182/blood-2006-04-015065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Haberichter SL, Castaman G, Budde U, Peake I, Goodeve A, Rodeghiero F, Federici AB, Batlle J, Meyer D, Mazurier C, Goudemand J, Eikenboom J, Schneppenheim R, Ingerslev J, Vorlova Z, Habart D, Holmberg L, Lethagen S, Pasi J, Hill FG, Montgomery RR. Identification of type 1 von Willebrand disease patients with reduced von Willebrand factor survival by assay of the VWF propeptide in the European study: molecular and clinical markers for the diagnosis and management of type 1 VWD (MCMDM-1VWD) Blood. 2008;111:4979–85. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-09-110940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Castaman G, Lethagen S, Federici AB, Tosetto A, Goodeve A, Budde U, Batlle J, Meyer D, Mazurier C, Fressinaud E, Goudemand J, Eikenboom J, Schneppenheim R, Ingerslev J, Vorlova Z, Habart D, Holmberg L, Pasi J, Hill F, Peake I, Rodeghiero F. Response to desmopressin is influenced by the genotype and phenotype in type 1 von Willebrand disease (VWD): results from the European Study MCMDM-1VWD. Blood. 2008;111:3531–9. doi: 10.1182/blood-2007-08-109231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Brown SA, Eldridge A, Collins PW, Bowen DJ. Increased clearance of von Willebrand factor antigen post-DDAVP in Type 1 von Willebrand disease: is it a potential pathogenic process? J Thromb Haemost. 2003;1:1714–7. doi: 10.1046/j.1538-7836.2003.00359.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rodeghiero F, Castaman G, Di Bona E, Ruggeri M, Lombardi R, Mannucci PM. Hyper-responsiveness to DDAVP for patients with type I von Willebrand's disease and normal intra-platelet von Willebrand factor. Eur J Haematol. 1988;40:163–7. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0609.1988.tb00815.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lenting PJ, CJ VANS, Denis CV. Clearance mechanisms of von Willebrand factor and factor VIII. J Thromb Haemost. 2007;5:1353–60. doi: 10.1111/j.1538-7836.2007.02572.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Casonato A, Pontara E, Sartorello F, Cattini MG, Gallinaro L, Bertomoro A, Rosato A, Padrini R, Pagnan A. Identifying type Vicenza von Willebrand disease. J Lab Clin Med. 2006;147:96–102. doi: 10.1016/j.lab.2005.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.