Abstract

The presence of DNA in the cytoplasm of mammalian cells is a danger signal that triggers the host immune responses such as the production of type-I interferons (IFN). Cytosolic DNA induces IFN through the production of cyclic-GMP-AMP (cGAMP), which binds to and activates the adaptor protein STING. Through biochemical fractionation and quantitative mass spectrometry, we identified a cGAMP synthase (cGAS), which belongs to the nucleotidyltransferase family. Overexpression of cGAS activated the transcription factor IRF3 and induced IFNβ in a STING-dependent manner. Knockdown of cGAS inhibited IRF3 activation and IFNβ induction by DNA transfection or DNA virus infection. cGAS bound to DNA in the cytoplasm and catalyzed cGAMP synthesis. These results indicate that cGAS is a cytosolic DNA sensor that induces interferons by producing the second messenger cGAMP.

DNA was known to stimulate immune responses long before it was shown to be a genetic material, but the mechanism by which DNA functions as an immune stimulant remains poorly understood(1). Although DNA can stimulate the production of type-I interferons in dendritic cells through binding to Toll-like receptor 9 (TLR9) in the endosome, how DNA in the cytosol induces IFN is still unclear. In particular, the sensor that detects cytosolic DNA in the interferon pathway remains elusive (2). Although several proteins, including DAI, RNA polymerase III, IFI16, DDX41 and several other DNA helicases, have been suggested to function as the potential DNA sensors that induce IFN, none has been met with universal acceptance(3).

Purification and identification of cyclic GMP-AMP synthase (cGAS)

We showed that delivery of DNA to mammalian cells or cytosolic extracts triggered the production of cyclic GMP-AMP (cGAMP), which bound to and activated STING, leading to the activation of IRF3 and induction of IFNβ (4). To identify the cGAMP synthase (cGAS), we fractionated cytosolic extracts (S100) from the murine fibrosarcoma cell line L929, which contains the cGAMP synthesizing activity. This activity was assayed by incubating the column fractions with ATP and GTP in the presence of herring testis DNA (HT-DNA). After digesting the DNA with Benzonase and heating at 95°C to denature proteins, the heat-resistant supernatants that contained cGAMP were incubated with Perfringolysin O (PFO)-permeabilized Raw264.7 cells (transformed mouse macrophages). cGAMP-induced IRF3 dimerization in these cells were analyzed by native gel electrophoresis (4). Using this assay, we carried out three independent routes of purification, each consisting of four steps of chromatography but differing in the columns or the order of the columns that were used (fig. S1A). In particular, the third route included an affinity purification step using a biotinylated DNA oligo (a 45-bp DNA known as Immune Stimulatory DNA or ISD). We estimated that we achieved a range of 8000 – 15,000 fold purification and 2–5% recovery of the activity from these routes of fractionation. However, in the last step of each of these purification routes, silver staining of the fractions did not reveal clear protein bands that co-purified with the cGAS activity, suggesting that the abundance of the putative cGAS protein might be very low in L929 cytosolic extracts.

We developed a quantitative mass spectrometry strategy to identify a list of proteins that co-purified with the cGAS activity at the last step of each purification route. We reasoned that the putative cGAS protein must co-purify with its activity in all three purification routes, whereas most ‘contaminating’ proteins would not. Thus, from the last step of each purification route, we chose fractions that contained most of the cGAS activity (peak fractions) and adjacent fractions that contained very weak or no activity (fig. S1B). The proteins in each fraction were separated by SDS-PAGE and identified by nano liquid chromatography mass spectrometry (nano-LC-MS). The data were analyzed by label-free quantification using the MaxQuant software (5), and the proteins that co-purified with the cGAS activity are shown in Supplementary Table 1 and illustrated in a Venn diagram (fig. S1C). Remarkably, although many proteins co-purified with the cGAS activity in one or two purification routes, only three proteins co-purified in all three routes. All three were putative uncharacterized proteins: E330016A19 (accession #: NP_775562), Arf-GAP with dual PH domain-containing protein 2 (NP_742145) and signal recognition particle 9 kDa protein (NP_036188). Among these, more than 24 unique peptides were identified in E330016A19, representing 41% coverage in this protein of 507 amino acids (fig. S2A).

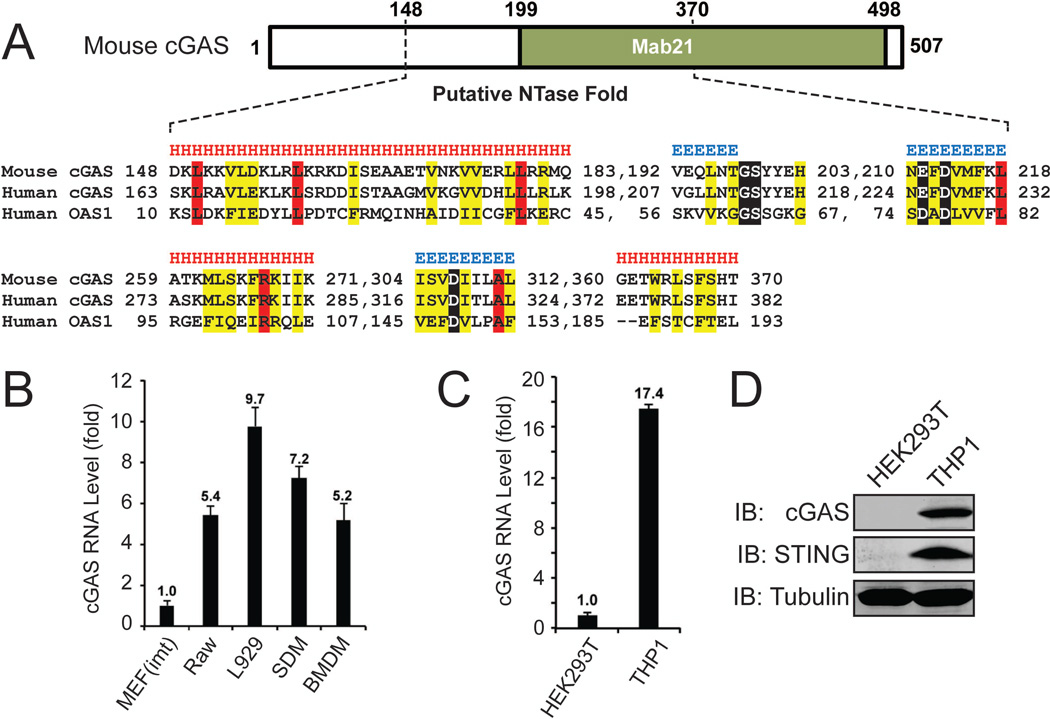

Bioinformatic analysis drew our attention to E330016A19, which exhibited structural and sequence homology to the catalytic domain of oligoadenylate synthase (OAS1) (Fig. 1A). In particular, E330016A19 contains a conserved G[G/S]x9–13[E/D]h[E/D]h motif, where x9–13 indicates 9–13 flanking residues consisting of any amino acid and h indicates a hydrophobic amino acid. This motif is found in the nucleotidyltransferase (NTase) family(6). Besides OAS1, this family includes adenylate cyclase, poly[A] polymerase and DNA polymerases. The C-terminus of E330016A19 contained a Male Abnormal 21 (Mab21) domain, which was first identified in the C. elegans protein Mab21 (7). Sequence alignment revealed that the C-terminal NTase and Mab21 domains are highly conserved from zebrafish to human (fig. S2B and S2C), whereas the N-terminal sequences are much less conserved (8). Interestingly, the human homologue of E330016A19, C6orf150 (also known as MB21D1) was recently identified as one of several positive hits in a screen for interferon-stimulated genes (ISGs) whose overexpression inhibited viral replication (9). For clarity and on the basis of evidence presented in this paper, we propose to name the mouse protein E330016A19 as m-cGAS and the human homologue C6orf150 as h-cGAS. Quantitative RT-PCR showed that the expression of m-cGAS was low in immortalized MEF cells but high in L929, Raw264.7 and bone marrow-derived macrophages (BMDM) (Fig. 1B). Similarly, the expression of h-cGAS RNA was very low in HEK293T cells but high in the human monocytic cell line THP1 (Fig. 1C). Immunoblotting further confirmed that h-cGAS protein was expressed in THP1 but not HEK293T cells (Fig. 1D; no mouse cGAS antibody is available yet.). Thus, the expression levels of m-cGAS and h-cGAS in different cell lines correlated with the ability of these cells to produce cGAMP and induce IFNβ in response to cytosolic DNA (4, 10).

Figure 1. Identification of a cGAMP synthase (cGAS).

(A) Multiple sequence and structure alignment of putative nucleotidyltransferase (NTase) domain of mouse cGAS, human cGAS and human OAS1 using the PROMALS3D program. Conserved active site residues of NTase superfamily are highlighted in black, identical amino acids in red and conserved amino acids in yellow. Predicted secondary structure is indicated above the alignment as alpha helices (H) and beta strands (E). (B and C) Quantitative RT-PCR analyses of cGAS RNA levels in different murine (B) and human (C) cell lines. MEF (imt): immortalized MEF; Raw: Raw264.7; SDM: spleen-derived macrophage; BMDM: bone marrow-derived macrophage. The error bars in this and all other q-RT-PCR assays represent standard errors of the mean (n=3). (D) Immunoblotting of endogenous human proteins in HEK293T and THP1 cells with the indicated antibodies.

Catalysis by cGAS triggers type-I interferon production

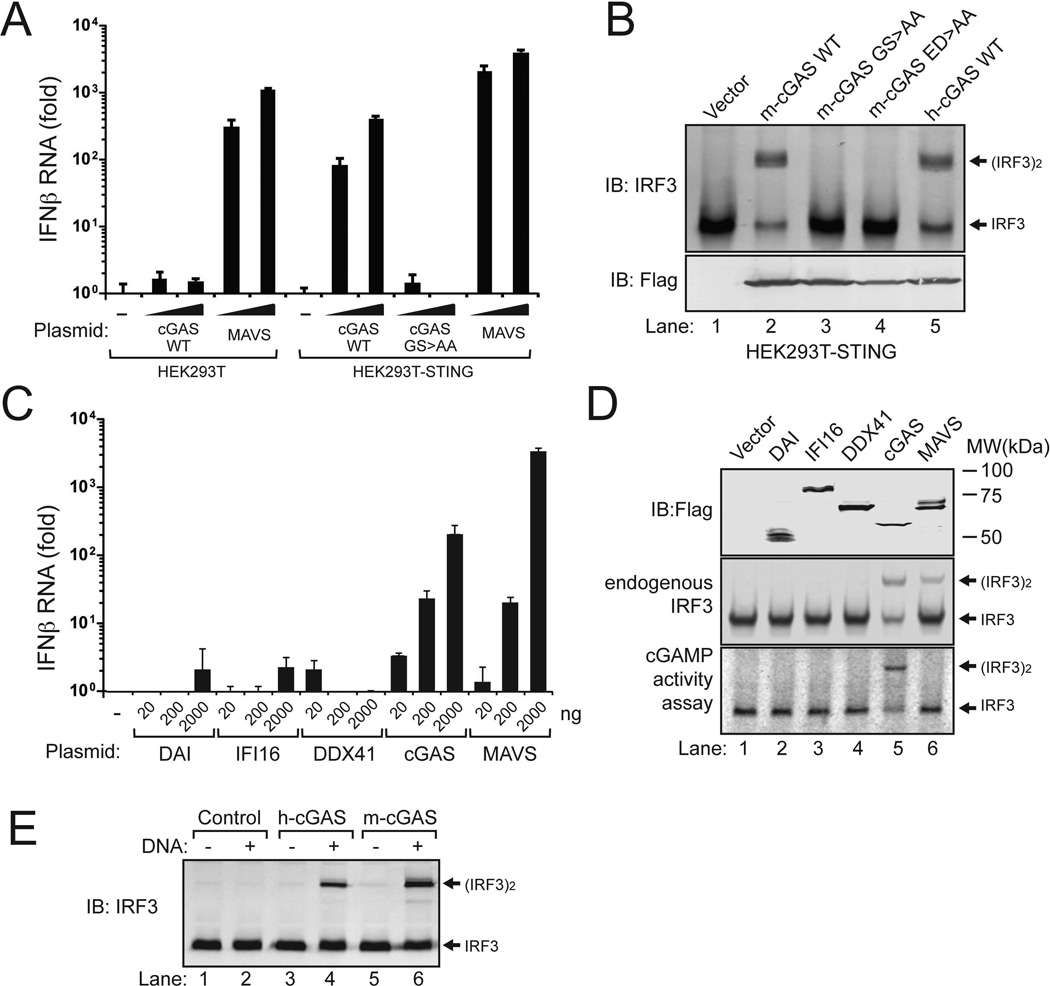

Overexpression of m-cGAS in HEK293T, which lacks STING expression (Fig. 1D), did not induce IFNβ, whereas stable expression of STING in HEK293T cells rendered these cells highly competent in IFNβ induction by m-cGAS (Fig. 2A). Importantly, point mutations of the putative catalytic residues G198 and S199 to alanine abolished the ability of m-cGAS to induce IFNβ. These mutations, as well as mutations of the other putative catalytic residues E211 and D213 to alanine, also abrogated the ability of m-cGAS to induce IRF3 dimerization in HEK293T-STING cells (Fig. 2B). The magnitude of IFNβ induction by c-GAS was comparable to that induced by MAVS (an adaptor protein that functions downstream of the RNA sensor RIG-I) and was several orders higher than those induced by other putative DNA sensors, including DAI, IFI16 and DDX41 (Fig. 2C). To determine if overexpression of cGAS and other putative DNA sensors led to the production of cGAMP in cells, supernatants from heat-treated cell extracts were incubated with PFO-permeabilized Raw264.7 cells, followed by measurement of IRF3 dimerization (Fig. 2D, bottom). Among all the proteins expressed in HEK293T-STING cells, only cGAS was capable of producing the cGAMP activity in the cells.

Figure 2. cGAS activates IRF3 and induces IFNβ.

(A) Expression plasmids (100 and 500 ng) encoding Flag-tagged mouse cGAS (m-cGAS), its active site mutants G198A/S199A (designated as GS>AA), and MAVS were transfected into HEK293T cells or the same cell line stably expressing STING (HEK293T-STING). 24 hr after transfection, IFNβ RNA was measured by q-RT-PCR. (B) Similar to (A), except that cell lysates were analyzed for IRF3 dimerization by native gel electrophoresis (top). The expression levels of the transfected genes were monitored by immunoblotting with a Flag antibody (bottom). h-cGAS: human cGAS; ED>AA: E211A/D213A in mouse cGAS. (C) Expression vectors for the indicated proteins were transfected into HEK293T-STING cells, followed by measurement of IFNβ by q-RT-PCR. (D) Cell lysates shown in (C) were immunoblotted with antibodies against Flag and IRF3 after SDS-PAGE and native PAGE, respectively (top two panels). Aliquots of the cell extracts were assayed for the presence of cGAMP activity, which was measured by detecting IRF3 dimerization after delivery into permeabilized Raw264.7 cells (bottom). (E) Human and mouse cGAS were expressed in HEK293T cells and affinity purified using a Flag antibody. The proteins were incubated with ATP and GTP in the presence or absence of HT-DNA, and the synthesis of cGAMP was assessed by its ability to induce IRF3 dimerization in Raw264.7 cells.

To test if cGAS could synthesize cGAMP in vitro, we purified wild-type (WT) and mutant Flag-cGAS proteins from transfected HEK293T cells. WT m-cGAS and h-cGAS, but not the catalytically inactive mutants of cGAS, were able to produce the cGAMP activity, which stimulated IRF3 dimerization in permeabilized Raw264.7 cells (fig. S3A). Importantly, the in vitro activities of both m-cGAS and h-cGAS were dependent on the presence of HT-DNA (Fig. 2E). To test if DNA enhances IFNβ induction by cGAS in cells, different amounts of cGAS expression plasmid was transfected with or without HT-DNA into HEK293T-STING cells (fig. S3B). HT-DNA significantly enhanced IFNβ induction by low (10 and 50 ng) but not high (200 ng) doses of cGAS plasmid. It is possible that the transfected cGAS plasmid DNA activated the cGAS protein in the cells, resulting in IFNβ induction. In contrast to cGAS, IFI16 and DDX41 did not induce IFNβ even when HT-DNA was co-transfected.

cGAS is required for IFNβ induction by DNA transfection and DNA virus infection

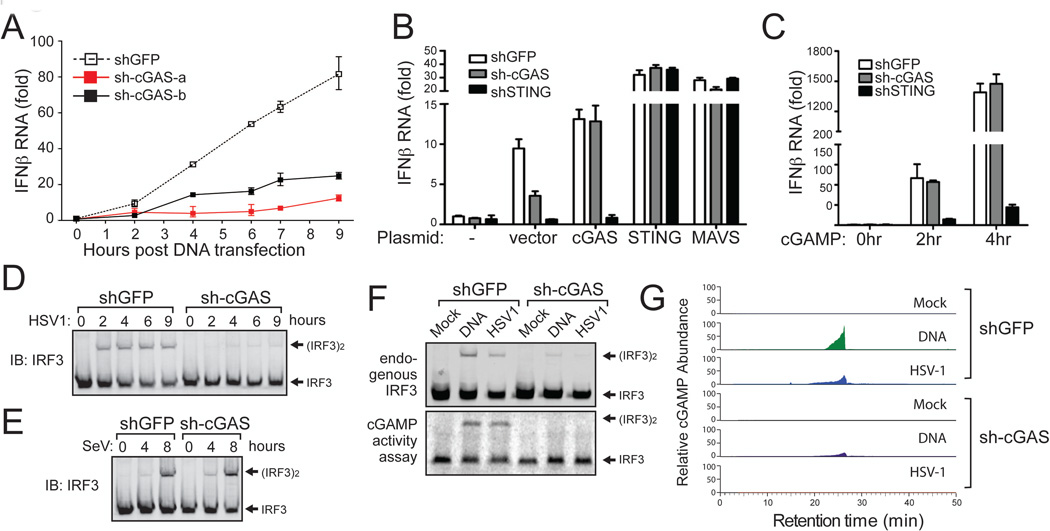

We used two different pairs of siRNA to knock down m-cGAS in L929 cells, and found that both siRNA oligos significantly inhibited IFNβ induction by HT-DNA, and that the degree of inhibition correlated with the efficiency of knocking down m-cGAS RNA (fig. S4A). We also established two L929 cell lines stably expressing shRNA sequences targeting distinct regions of m-cGAS (fig. S4B). The ability of these cells to induce IFNβ in response to HT-DNA was severely compromised as compared to another cell line expressing a control shRNA (GFP; Fig. 3A). Importantly, expression of cGAS in the L929-sh-cGAS cells restored IFNβ induction (Fig. 3B). Expression of STING or MAVS in L929-sh-cGAS cells (Fig. 3B) or delivery of cGAMP to these cells (Fig. 3C) also induced IFNβ. In contrast, expression of cGAS or delivery of cGAMP failed to induce IFNβ in L929-shSTING cells, whereas expression of STING or MAVS restored IFNβ induction in these cells (Fig. 3B and 3C). Quantitative RT-PCR analyses confirmed the specificity and efficiency of knocking down cGAS and STING in the L929 cell lines stably expressing the corresponding shRNAs (fig. S4C). These results indicate that cGAS functions upstream of STING and is required for IFNβ induction by cytosolic DNA.

Figure 3. cGAS is essential for IRF3 activation and IFNβ induction by DNA transfection and DNA virus infection.

(A) L929 cell lines stably expressing shRNA targeting GFP (control) or two different regions of m-cGAS were transfected with HT-DNA for indicated times, followed by measurement of IFNβ RNA by q-RT-PCR. See fig. S4B for RNAi efficiency. (B) L929 cells stably expressing shRNA against GFP, cGAS or STING were transfected with pcDNA3 (vector) or the same vector driving the expression of indicated proteins. 24 hr after transfection, IFNβ RNA was measured by q-RT-PCR. see fig. S4C for RNAi efficiency. (C) cGAMP (100 nM) was delivered to digitoninpermeabilized L929/shRNA cells as indicated. IFNβ RNA was measured by q-RT-PCR at indicated times following cGAMP delivery. (D and E) L929-shRNA cells as indicated were infected with HSV1 (ΔICP34.5) or Sendai virus (SeV) for indicated times followed by measurement of IRF3 dimerization. (F) L929/shRNA cells were transfected with HT-DNA or infected with HSV1 for 6 hr, followed by measurement of IRF3 dimerization (top). Extracts from these cells were used to prepare heat-resistant supernatants, which were delivered to permeabilized Raw264.7 cells to stimulate IRF3 dimerization (bottom). (G) The heat-resistant supernatants in (F) were fractionated by HPLC using a C18 column and the abundance of cGAMP was quantitated by mass spectrometry using SRM.

Herpes simplex virus 1 (HSV-1) is a DNA virus known to induce IFNs through the activation of STING and IRF3(3). Importantly, shRNA against m-cGAS, but not GFP, in L929 cells strongly inhibited IRF3 dimerization induced by HSV-1 infection (Fig. 3D). In contrast, knockdown of cGAS did not affect IRF3 activation by Sendai virus, an RNA virus (Fig. 3E). To determine if cGAS is required for the generation of cGAMP in cells, we transfected HT-DNA into L929-shGFP and L929-sh-cGAS or infected these cells with HSV-1, then prepared heat-resistant fractions that contained cGAMP, which was subsequently delivered to permeabilized Raw264.7 cells to measure IRF3 activation. Knockdown of cGAS largely abolished the cGAMP activity generated by DNA transfection or HSV-1 infection (Fig. 3F, bottom). Quantitative mass spectrometry using selective reaction monitoring (SRM) showed that the abundance of cGAMP induced by DNA transfection or HSV-1 infection was markedly reduced in L929 cells depleted of cGAS (Fig. 3G). Taken together, these results demonstrate that cGAS is essential for producing cGAMP and activating IRF3 in response to DNA transfection or HSV-1 infection.

To determine if cGAS is important in the DNA sensing pathway in human cells, we established a THP1 cell line stably expressing a shRNA targeting h-cGAS (fig. S4D). The knockdown of h-cGAS strongly inhibited IFNβ induction by HT-DNA transfection or infection by vaccinia virus, another DNA virus, but not Sendai virus (fig. S4D). The knockdown of h-cGAS also inhibited IRF3 dimerization induced by HSV-1 infection in THP1 cells (fig. S4E). This result was further confirmed in another THP1 cell line expressing a shRNA targeting a different region of h-cGAS (fig. S4F). The strong and specific effects of multiple cGAS shRNA sequences in inhibiting DNA-induced IRF3 activation and IFNβ induction in both mouse and human cell lines demonstrate a key role of cGAS in the STING-dependent DNA sensing pathway.

Recombinant cGAS protein catalyzes cGAMP synthesis from ATP and GTP in a DNA-dependent manner

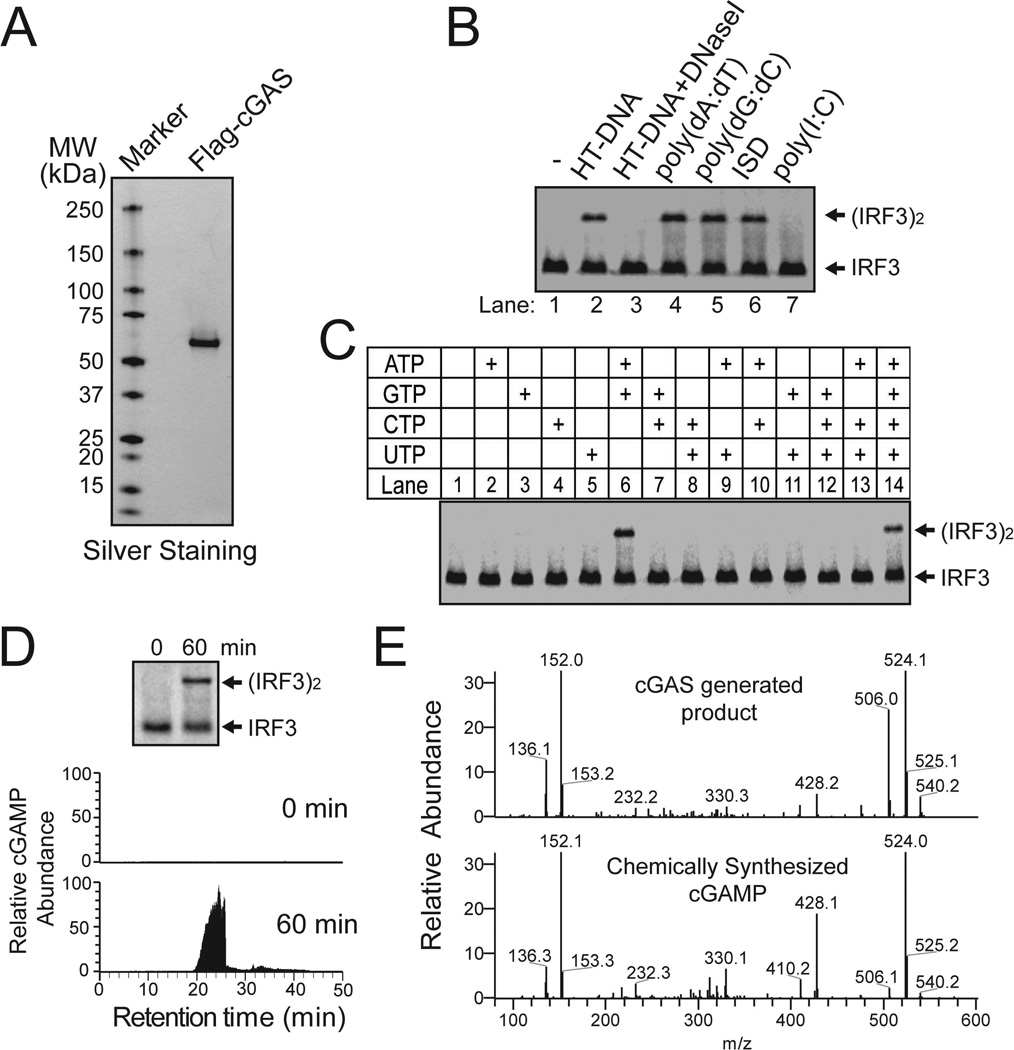

To test if cGAS is sufficient to catalyze cGAMP synthesis, we expressed Flag-tagged h-cGAS in HEK293T cells and purified it to apparent homogeneity (Fig. 4A). In the presence of HT-DNA, purified c-GAS protein catalyzed the production of cGAMP activity, which stimulated IRF3 dimerization in permeabilized Raw264.7 cells (Fig. 4B). DNase-I treatment abolished this activity. The cGAS activity was also stimulated by other DNA, including poly(dA:dT), poly(dG:dC) and ISD, but not the RNA poly(I:C). The synthesis of cGAMP by cGAS required both ATP and GTP, but not CTP or UTP (Fig. 4C). These results indicate that the cyclase activity of purified cGAS protein was stimulated by DNA but not RNA.

Figure 4. DNA-dependent synthesis of cGAMP by purified cGAS.

(A) Silver staining of Flag-h-cGAS expressed and purified from HEK293T cells. (B) Purified Flag-h-cGAS as shown in (A) was incubated with ATP and GTP, in the presence of different forms of nucleic acids as indicated. Generation of cGAMP was assessed by its ability to induce IRF3 dimerization in Raw264.7 cells. (C) Similar to (B), except that reactions contained HT-DNA and different combinations of NTP as indicated. (D) Similar to (B), except that WT and mutant cGAS proteins were expressed and purified from E. coli and assayed for their activities at indicated concentrations. (E) Purified m-cGAS from E coli was incubated with ATP, GTP and DNA for 0 or 60 min, and the production of cGAMP was analyzed by IRF3 dimerization assay (top) and mass spectrometry using SRM (bottom).

We also expressed m-cGAS in E. coli as a SUMO fusion protein. After purification, Sumo-m-cGAS generated the cGAMP activity in a DNA-dependent manner (fig. S5, A and C). However, after the SUMO tag was removed by a Sumo protease, the m-cGAS protein catalyzed cGAMP synthesis in a DNA-independent manner (fig. S5, B and C). The reason for this loss of DNA dependency is unclear, but could be due to some conformational changes after Sumo removal. Titration experiments showed that less than 1 nM of the recombinant cGAS protein led to detectable IRF3 dimerization, whereas the catalytically inactive mutant of cGAS failed to activate IRF3 even at high concentrations (Fig. 4D). To formally prove that cGAS catalyzes the synthesis of cGAMP, the reaction products were analyzed by nano-LC-MS using SRM. cGAMP was detected in a 60-min reaction containing purified cGAS, ATP and GTP (Fig. 4E). The identity of cGAMP was further confirmed by ion fragmentation using collision-induced dissociation (CID). The fragmentation pattern of cGAMP synthesized by purified cGAS revealed product ions whose m/z values matched those of chemically synthesized cGAMP (fig. S5D). Collectively, these results demonstrate that purified cGAS catalyzes the synthesis of cGAMP from ATP and GTP.

cGAS binds to DNA

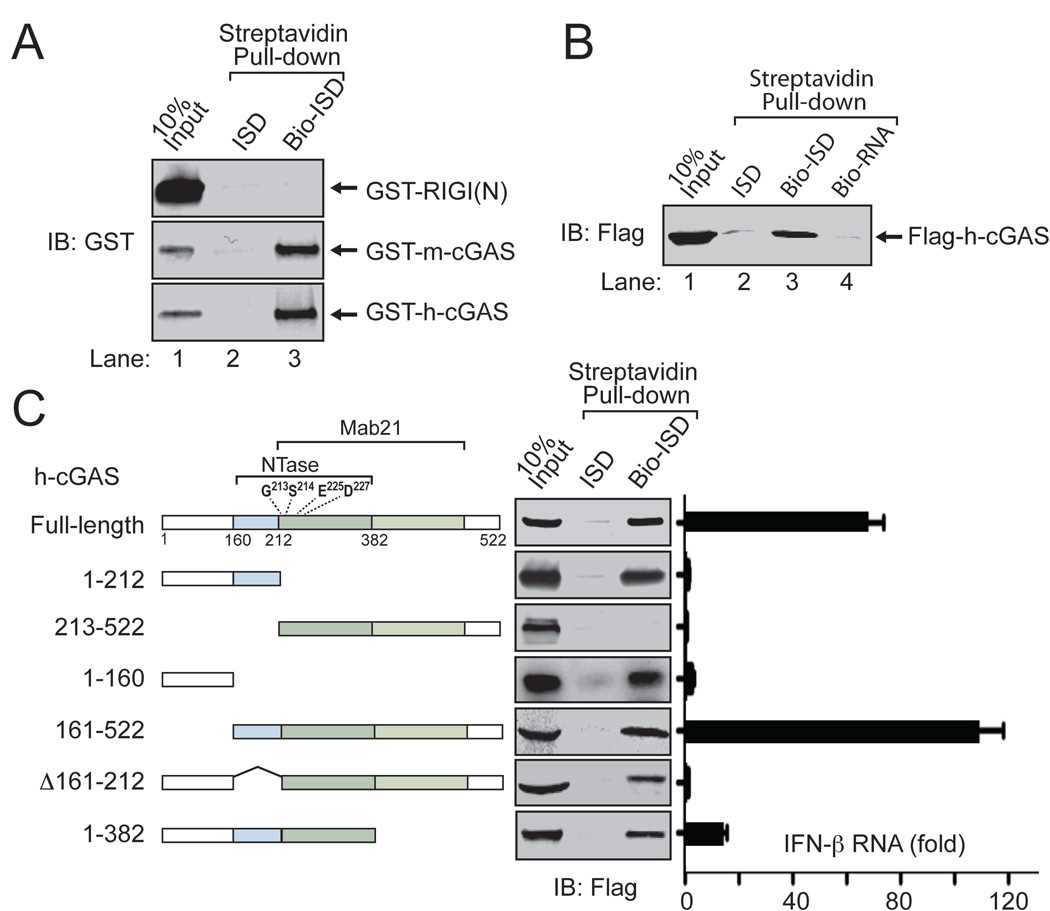

The stimulation of cGAS activity by DNA suggests that c-GAS is a DNA sensor (Fig. 4B). Indeed, both GST-m-cGAS and GST-h-cGAS, but not GST-RIG-I N-terminus [RIG-I(N)], were precipitated by biotinylated ISD (Fig. 5A). In contrast, biotinylated RNA did not bind cGAS (Fig. 5B). Deletion analyses showed that the h-cGAS N-terminal fragment containing residues 1–212, but not the C-terminal fragment 213–522, bound to ISD (Fig. 5C). A longer C-terminal fragment containing residues 161–522 did bind to ISD, suggesting that the sequence 161–212 may be important for DNA binding. However, deletion of residues 161–212 from h-cGAS did not significantly impair ISD binding, suggesting that cGAS contains another DNA binding domain at the N-terminus. Indeed, the N-terminal fragment containing residues 1–160 also bound ISD (Fig. 5C). Thus, cGAS may contain two separate DNA binding domains at the N-terminus. However, our attempts to express the cGAS fragment 161–212 in E. coli or HEK293T cells have not been successful, so at present we do not know if this sequence alone is sufficient to bind DNA. Nevertheless, it is clear that the N-terminus of h-cGAS containing residues 1–212 is both necessary and sufficient to bind DNA.

Figure 5. cGAS is a DNA binding protein.

(A) Indicated GST fusion proteins were expressed and purified from E. coli and then incubated with Streptavidin beads in the presence of ISD or biotin-ISD. Bound proteins were eluted with SDS sample buffer and detected by immunoblotting with a GST antibody. (B) Flag-h-cGAS was expressed and purified from HEK293T cells and then incubated with streptavidin beads as described in (A) except that a Flag antibody was used in immunoblotting and a biotin-RNA was also tested for binding to cGAS. (C) Flag-tagged full-length or truncated human cGAS proteins were expressed in HEK293T cells and affinity purified. Their ability to bind biotin-ISD was assayed as described in (B). Right panel: Expression plasmids encoding full-length and deletion mutants of h-cGAS were transfected into HEK293T-STING cells followed by measurement of IFNβ RNA by q-RT-PCR.

Different deletion mutants of h-cGAS were overexpressed in HEK293T-STING cells to determine their ability to activate IRF3 and induce IFNβ and the cytokine tumor necrosis factor α (TNFα) (Fig. 5C and fig. S6A). The protein fragment 1–382, which lacks the C-terminal 140 residues including much of the Mab21 domain, failed to induce IFNβ (Fig. 5C, right) or TNFα or to activate IRF3 (fig. S6A), suggesting that an intact Mab21 domain is important for cGAS function. As expected, deletion of the N-terminal 212 residues (fragment 213–522), which include part of the NTase domain, abolished the cGAS activity (Fig. 5C and fig. S6A). An internal deletion of just four amino acids (KLKL, Δ171–174) within the first helix of the NTase fold preceding the catalytic residues also destroyed the cGAS activity (fig. S6A). Interestingly, deletion of the N-terminal 160 residues did not affect IRF3 activation or cytokine induction by cGAS (Fig. 5C and fig. S6A). In vitro assay showed that this protein fragment (161–522) still activated the IRF3 pathway in a DNA-dependent manner (fig. S6B). Thus, the N-terminal 160 amino acids of h-cGAS, whose primary sequence is not highly conserved evolutionarily, appears to be largely dispensable for DNA binding and catalysis by cGAS. In contrast, the NTase and Mab21 domains are important for cGAS activity.

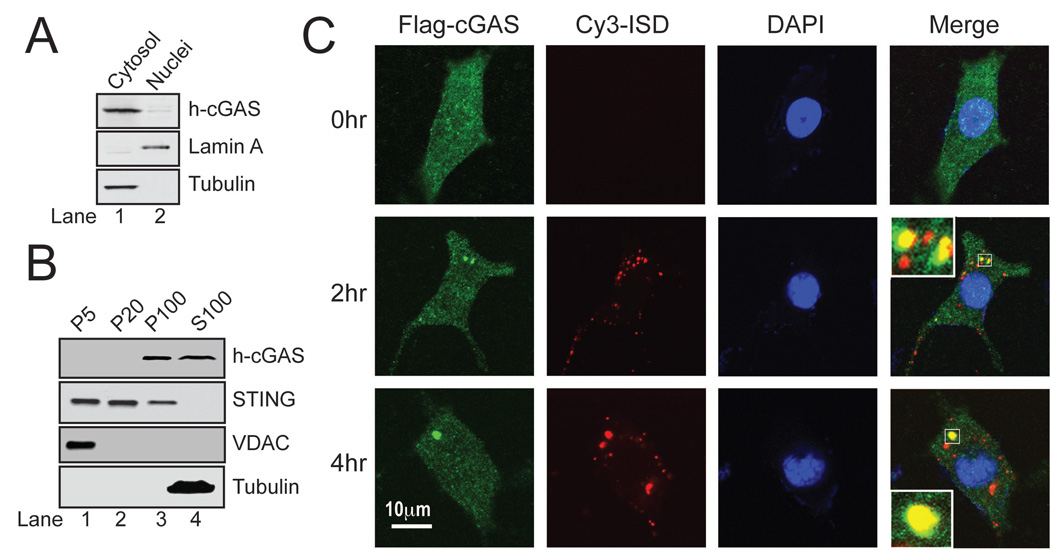

cGAS is predominantly localized in the cytosol

To determine if cGAS is a cytosolic DNA sensor, we prepared cytosolic and nuclear extracts from THP1 cells and analyzed the localization of endogenous h-cGAS by immunoblotting. h-cGAS was detected in the cytosolic extracts, but barely detectable in the nuclear extracts (Fig. 6A). The THP1 extracts were further subjected to differential centrifugation to separate subcellular organelles from one another and from the cytosol (Fig. 6B). Similar amounts of h-cGAS were detected in S100 and P100 (pellet after 100,000 × g centrifugation), suggesting that this protein is soluble in the cytoplasm but a significant fraction of the protein is associated with light vesicles or organelles. The cGAS protein was not detected in P5, which contained mitochondria and ER as evidenced by the presence of VDAC and STING, respectively. cGAS was also not detectable in P20, which contained predominantly ER and heavy vesicles (Fig. 6B).

Figure 6. cGAS binds to DNA in the cytoplasm.

(A) Nuclear and cytoplasmic fractions were prepared from THP-1 cells and analyzed by immunoblotting with the indicated antibodies. (B) THP-1 cells were homogenized in hypotonic buffer and subjected to differential centrifugation. Pellets at different speeds of centrifugation (e.g, P100: pellets after 100,000 × g) and S100 were immunoblotted with the indicated antibodies. (C) L929 cells stably expressing Flag-cGAS (green) were transfected with Cy3-ISD (red). At different time points after tranfection, cells were fixed, stained with the Flag antibody or DAPI and imaged by confocal fluorescence microscopy. Inset: magnification of the area outlined in the merged images. These images are representative of at least 10 cells at each time point (representing > 50% of the cells under examination).

We also examined the localization of cGAS by confocal immunofluorescence microscopy using L929 cells stably expressing Flag-m-cGAS (Fig. 6C). The cGAS protein distributed throughout the cytoplasm but could also be observed in the nuclear or peri-nuclear region. Interestingly, after the cells were transfected with Cy3-labelled ISD for 2 or 4 hours, punctate forms of cGAS were observed and they overlapped with the DNA fluorescence. Such co-localization and apparent aggregation of cGAS and Cy3-ISD was observed in more than 50% of the cells under observation. These results, together with the biochemical evidence of direct binding of cGAS with DNA, suggest that cGAS binds to DNA in the cytoplasm.

Discussion

In this report, we developed a strategy that combined quantitative mass spectrometry with conventional protein purification to identify biologically active proteins that were partially purified from crude cell extracts. This strategy may be generally applicable to proteins that are difficult to be purified to homogeneity due to very low abundance, labile activity or scarce starting materials. As a proof of principle, we used this strategy to identify the mouse protein E330016A19 as the enzyme that synthesizes cGAMP. This discovery led to the identification of a large family of cGAS that is conserved from fish to human, formally demonstrating that vertebrate animals contain evolutionarily conserved enzymes that synthesize cyclic di-nucleotides, which were previously found only in bacteria, archaea and protozoan (11–13). Vibrio cholera can synthesize cGAMP through its cyclase DncV (VC0179), which contains an NTase domain, but lacks significant primary sequence homology to the mammalian cGAS(12).

Our results not only demonstrate that cGAS is a cytosolic DNA sensor that triggers the type-I interferon pathway, but also reveal a novel mechanism of immune signaling in which cGAS generates the second messenger cGAMP, which binds to and activates STING (4), thereby triggering type-I interferon production. It remains to be determined whether STING evolved first to detect cyclic di-nucleotides from bacteria, or endogenous cGAMP in the host as a mechanism of responding to cytosolic DNA. The deployment of cGAS as a cytosolic DNA sensor greatly expands the repertoire of microorganisms detected by the host immune system. In principle, all microorganisms that can carry DNA into the host cytoplasm, such as DNA viruses, bacteria, parasites (e.g, malaria) and retroviruses (e.g, HIV), could potentially trigger the cGAS-STING pathway (14, 15). The enzymatic synthesis of cGAMP by cGAS provides a mechanism of signal amplification for a robust and sensitive immune response. However, the detection of self DNA in the host cytoplasm by cGAS could also lead to autoimmune diseases, such as systemic lupus erythematosus, Sjögren’s syndrome, and Aicardi-Goutières syndrome (16–18).

Several other DNA sensors, such as DAI, IFI16 and DDX41, have been reported to induce type-I interferons (19–21). Overexpression of DAI, IFI16 or DDX41 did not lead to the production of cGAMP. We also found that knockdown of DDX41 and p204 (a mouse homologue of IFI16) by siRNA did not inhibit the generation of cGAMP activity in HT-DNA transfected L929 cells (fig. S7). Nevertheless, it is possible that distinct DNA sensors exist in different cell types. Unlike other putative DNA sensors and most pattern recognition receptors (e.g, TLRs), cGAS is a cyclase that is likely more amenable to inhibition by small molecule compounds. These inhibitors may be developed into therapeutic agents for the treatment of human autoimmune diseases.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We thank W. Li for helpful discussion on bioinformatics analyses. The data presented in this paper are tabulated in the main paper and in the supplementary materials. The GenBank accession numbers for human and mouse cGAS sequences are KC294566 and KC294567. This work was supported by a grant from NIH (AI-093967). Z. J. C is an investigator of Howard Hughes Medical Institute.

References and Notes

- 1.O'Neill LA. DNA makes RNA makes innate immunity. Cell. 2009 Aug 7;138:428. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.07.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Barber GN. Cytoplasmic DNA innate immune pathways. Immunological reviews. 2011 Sep;243:99. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01051.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Keating SE, Baran M, Bowie AG. Cytosolic DNA sensors regulating type I interferon induction. Trends in immunology. 2011 Dec;32:574. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wu J, et al. Cyclic-GMP-AMP is an endogenous second messenger in innate immune signaling by cytosolic DNA. Science. 2012 doi: 10.1126/science.1229963. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cox J, Mann M. MaxQuant enables high peptide identification rates, individualized p.p.b.-range mass accuracies and proteome-wide protein quantification. Nat Biotechnol. 2008 Dec;26:1367. doi: 10.1038/nbt.1511. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuchta K, Knizewski L, Wyrwicz LS, Rychlewski L, Ginalski K. Comprehensive classification of nucleotidyltransferase fold proteins: identification of novel families and their representatives in human. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009 Dec;37:7701. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkp854. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chow KL, Hall DH, Emmons SW. The mab-21 gene of Caenorhabditis elegans encodes a novel protein required for choice of alternate cell fates. Development. 1995 Nov;121:3615. doi: 10.1242/dev.121.11.3615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pei J, Kim BH, Grishin NV. PROMALS3D: a tool for multiple protein sequence and structure alignments. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008 Apr;36:2295. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkn072. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schoggins JW, et al. A diverse range of gene products are effectors of the type I interferon antiviral response. Nature. 2011 Apr 28;472:481. doi: 10.1038/nature09907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chiu YH, Macmillan JB, Chen ZJ. RNA polymerase III detects cytosolic DNA and induces type I interferons through the RIG-I pathway. Cell. 2009 Aug 7;138:576. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2009.06.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pesavento C, Hengge R. Bacterial nucleotide-based second messengers. Curr Opin Microbiol. 2009 Apr;12:170. doi: 10.1016/j.mib.2009.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Davies BW, Bogard RW, Young TS, Mekalanos JJ. Coordinated regulation of accessory genetic elements produces cyclic di-nucleotides for V. cholerae virulence. Cell. 2012 Apr 13;149:358. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chen ZH, Schaap P. The prokaryote messenger c-di-GMP triggers stalk cell differentiation in Dictyostelium. Nature. 2012 Aug 30;488:680. doi: 10.1038/nature11313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sharma S, et al. Innate immune recognition of an AT-rich stem-loop DNA motif in the Plasmodium falciparum genome. Immunity. 2011 Aug 26;35:194. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2011.05.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Yan N, Chen ZJ. Intrinsic antiviral immunity. Nat Immunol. 2012;13:214. doi: 10.1038/ni.2229. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pascual V, Farkas L, Banchereau J. Systemic lupus erythematosus: all roads lead to type I interferons. Current opinion in immunology. 2006 Dec;18:676. doi: 10.1016/j.coi.2006.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao Y, Liu Z, Jallal B, Shen N, Ronnblom L. Type I Interferons in Sjogren's Syndrome. Autoimmunity reviews. 2012 Nov 29; doi: 10.1016/j.autrev.2012.10.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rigby RE, Leitch A, Jackson AP. Nucleic acid-mediated inflammatory diseases. Bioessays. 2008 Sep;30:833. doi: 10.1002/bies.20808. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Takaoka A, et al. DAI (DLM-1/ZBP1) is a cytosolic DNA sensor and an activator of innate immune response. Nature. 2007 Jul 26;448:501. doi: 10.1038/nature06013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Unterholzner L, et al. IFI16 is an innate immune sensor for intracellular DNA. Nature immunology. 2010 Nov;11:997. doi: 10.1038/ni.1932. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zhang Z, et al. The helicase DDX41 senses intracellular DNA mediated by the adaptor STING in dendritic cells. Nature immunology. 2011 Oct;12:959. doi: 10.1038/ni.2091. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.