Abstract

Background

Near-infrared spectroscopy is used during cardiac surgery to monitor the adequacy of cerebral perfusion. In this systematic review, we evaluated available data for adult patients to determine (1) whether decrements in cerebral oximetry during cardiac surgery are associated with stroke, postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD), or delirium and (2) whether interventions aimed at correcting cerebral oximetry decrements improve neurologic outcomes.

Methods

We searched PubMed, Cochrane, and Embase databases from inception until January 31, 2012, without restriction on languages. Each article was examined for additional references. A publication was excluded if it did not include original data (e.g., review, commentary) or if it was not published as a full-length article in a peer-reviewed journal (e.g., abstract only). The identified abstracts were screened first, and full texts of eligible papers were reviewed independently by two investigators. For eligible publications, we recorded the number of subjects, type of surgery, and criteria for diagnosis of neurologic endpoints.

Results

We identified 13 case reports, 27 observational studies, and two prospectively randomized intervention trials that met our inclusion criteria. Case reports and two observational studies contained anecdotal evidence suggesting that regional cerebral O2 saturation (rScO2) monitoring could be used to identify cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) cannula malposition. Six of nine observational studies reported an association between acute rScO2 desaturation and POCD based on the Mini-Mental Status Examination (n=3 studies) or more detailed cognitive testing (n=6 studies). Two retrospective studies reported a relationship between rScO2 desaturation and stroke or type I and II neurologic injury after surgery. The observational studies had many limitations, including small sample size, assessments only during the immediate postoperative period, and failure to perform risk adjustments. Two randomized studies evaluated the efficacy of interventions for treating rScO2 desaturation during surgery, but adherence to the protocol was poor in one. In the other study, interventions for rScO2 desaturation were associated with less major organ injury and shorter intensive care unit hospitalization compared with nonintervention.

Conclusions

Reductions in rScO2 during cardiac surgery may identify CPB cannula malposition, particularly during aortic surgery. Only low-level evidence links low rScO2 during cardiac surgery to postoperative neurologic complications, and data are insufficient to conclude that interventions to improve rScO2 desaturation prevent stroke or POCD.

INTRODUCTION

Monitoring of regional cerebral O2 saturation (rScO2) with near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) became possible following pioneering work Jöbsis1 who demonstrated that light in the near-infrared spectrum penetrates the skull allowing measurement brain oxy- and deoxy-hemoglobin concentrations. The clinical feasibility of rScO2 monitoring of the adequacy of cerebral perfusion during cardiac surgery soon followed.2,3,4 In the US clinicians can now choose from five Food and Drug Administration approved NIRS devices made by four manufacturers (INOVS™, Somanetics/Covidien, Inc, Boulder, CO; FORE-SIGHT™, CAS Medical Systems, Branford, CN; EQUANOX™, Nonin Medical Inc, Plymouth, MN; CerOx™, Ornim Medical, Lod, Isreal ). Other monitors available outside the US include the NIRO (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan) and the TOS-96 (Tostec, Tokyo, Japan) monitors. Although many difference exist between in the methods for rScO2 monitoring between manufacturer, NIRS devices all follow several basic principles as previously reviewed.35,46 Noninvasive, self-adhesive optode pads applied to the skin of the forehead emit light in the near-infrared spectrum that is measured by sensors at set distances from the light source. When the intensity of light is constant, the strength of light detected at the sensors is inversely related to the concentration of light absorbing molecules, or chromophores. Oxyhemoglobin and deoxyhemoglobin have different and characteristic peak absorption in the near-infrared spectrum, but both absorb light at an isobestic wavelength around 800 nm. The absorption of light at the isobestic wavelength allows for the measurement of total hemoglobin concentration. Thus, using a modification of the Beer-Lambert law, NIRS provides the measurement of the concentration of oxygenated hemoglobin in relation to total hemoglobin concentration. The distance of the sensor from the light source determines the spatial resolution of the emitted light.

Many clinical devices usea proprietary algorithm for subtracting O2 saturation from superficial tissue (ie, bone and extra-cerebral tissue), from that obtained from deeper tissue to yield rScO2 value from the superficial frontal cortex (Figure 1). Unlike pulse oximetry, NIRS monitoring does not distinguish between arterial and venous blood. Because approximately 70% to 80% of cerebral blood is venous blood, rScO2 provides an indicator of the balance between regional O2 supply and demand.34

Figure 1.

Graphic illustration of basic near infrared spectroscopy methods. A non-adhesive optode placed on the forehead emits light that is detected by sensors at set distances from the light source. The spacial resolution of the curvilinear light pathway is dependent on the intensity of light as well as the distance of the sensors from the light source. The light source, wavelengths utilized, as well as the number and location of the sensors in relation to the light source varies between manufacturer. Subtraction algorithms are used to account for light absorption from superficial mostly extra-cranial tissue (in this example, the proximal sensor) from light absorbed by deeper structures (in this example, the distal sensor) yielding the regional cerebral oxygen saturation.

NIRS is increasingly used to monitor patients undergoing cardiac surgery. An objective evaluation of the benefits and costs (> $200 per patient) of NIRS monitoring is needed to assess the potential added value of its use. In 2005, Taillefer and Denault7 reported a systematic review of the clinical efficacy of NIRS monitoring that included many abstracts from scientific meetings that have not since undergone peer review. Since that review was published, a variety of observational studies, case reports, and prospectively randomized studies of NIRS monitoring have been published.8,9 Therefore, we performed a systematic review of the clinical efficacy of NIRS monitoring in adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery to address (1) whether acute decrements in rScO2 during surgery are associated with perioperative stroke or other neurologic dysfunction manifest as delirium or postoperative cognitive dysfunction (POCD) and (2) whether interventions based on rScO2 monitoring during cardiac surgery lead to improved neurologic or other patient outcomes.

METHODS

We identified relevant publications by searching PubMed, Embase, and Cochrane databases from inception through January 31, 2012. Our strategy combined two broad search terms: “near infrared spectroscopy” and “cardiac surgery.” The search was not limited by languages or date, but it was limited to adult patients. The NIRS category combined the results from MeSH (medical subject headings) terms and the following keywords: “spectroscopy, near-infrared,” “spectroscopy,” “near-infrared,” “near-infrared spectroscopy,” “near infrared spectroscopy,” “NIRS,” “cerebral oximetry.” The cardiac surgery search category combined the results from MeSH terms and the following keywords: “cardiac surgery,” “heart surgery,” “cardiac surgical procedures,” “cardiac surgery,” “cardiac bypass,” “cardiopulmonary bypass,” “coronary artery bypass,” “CABG,” “coronary bypass graft,” “CAB”. These two broad categories were examined together to ensure that the resulting articles would include only studies that pertain to NIRS use in cardiac surgery patients. In addition, we looked through the secondary references in the retrieved papers to capture articles that might have been missed. Lastly, we visited web sites of manufacturers of approved NIRS monitors to ensure that no relevant articles were missed. The review was limited to adult patients as the disease processes necessitating cardiac surgery differ between pediatric and adult patients (congenital vs acquired heart disease). Further, adult patients often have co-existing diseases including diabetes, hypertension, and cerebral vascular disease that affects cerebral oxygen balance while neonates and children may have right-to-left shunting reducing rScO2. Finally, the manifestations of neurologic injury may vary between adults and pediatric patients.

Publications were included in this review if they addressed either of the following questions: (1) Do decrements in cerebral oximetry lead to stroke or other neurologic dysfunction in adult patients undergoing cardiac surgery? and (2) Do interventions performed based on NIRS results lead to improved neurologic or other patient outcomes? We excluded publications if they did not include original data (e.g., review, commentary) or if they had not been published as a full-length article in a peer-reviewed journal (e.g., abstract only). Each title and/or abstract identified was screened for eligibility, and the full text of eligible papers was then reviewed independently by two investigators (FZ, MSY, RS, MO, or YZ). Data regarding the number of subjects, type of surgery, and criteria for diagnosis of neurologic endpoints were recorded. Other study outcomes were recorded when reported. Only the latest publication was included when duplicate reporting of subjects could not be excluded. The articles were classified as case reports, observational studies, and prospectively randomizes studies.

RESULTS

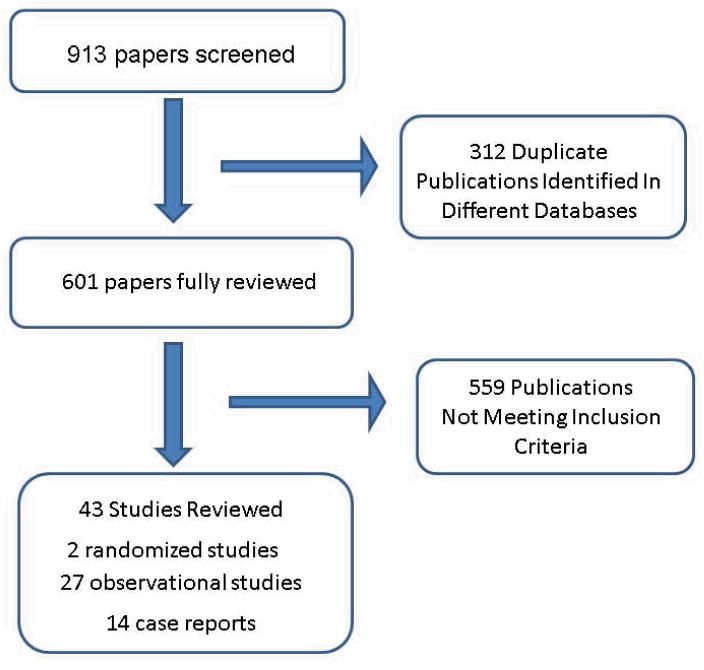

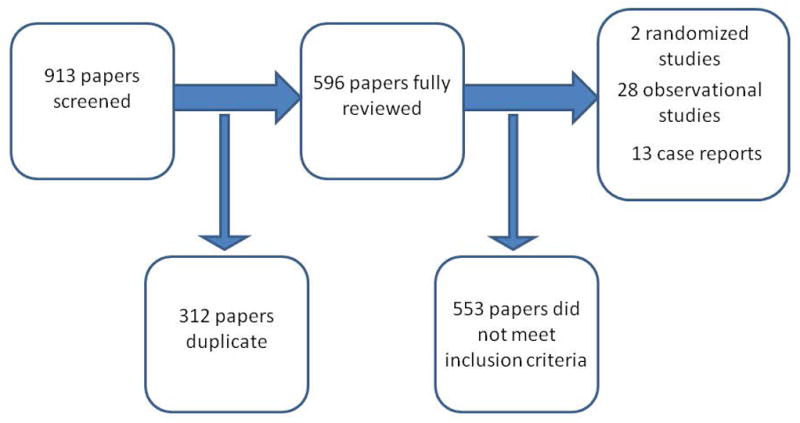

Figure 2 shows a summary of our search results. The initial strategy identified 913 citations, of which 312 were duplicated studies from the different databases. Review of the abstracts of the remaining citations led to the exclusion of an additional 559 papers for not meeting the inclusion criteria of this review. The latter included 176 papers that involved patients undergoing noncardiac surgery, 298 studies of pediatric patients, 55 animal studies, 16 studies that did not include cerebral NIRS monitoring, and 14 studies that did not assess neurologic outcomes. We reviewed the remaining 43 full-length manuscripts, which included a total of 51698 patients.

Figure 2.

Flow diagram of search results.

Case Reports

Fourteen case reports were identified that described patients undergoing coronary artery bypass surgery, valvular surgery, or aortic arch repair (Table 1).10–23 The authors of these reports suggested that rScO2 monitoring provided warning of cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) arterial or venous cannula malposition and prompted surgical correction.10,12, 14,22 In one report, oxygen delivery failure to the CPB circuit was first detected by abrupt decrease in rScO2 during surgery.20 Only clinical neurologic assessments were provided in these case reports. In one report the patient was reported to suffer from severe delirium based on clinical exam.15

Table 1.

Case reports reporting benefits of near infrared spectroscopy (NIRS), regional cerebral oxygen saturation (rScO2) monitoring.

| Article | Surgery type/NIRS device used for monitoring | Major findings |

|---|---|---|

| Aono M10 | Aortic surgery with DHCA INVOS™3100 |

Monitoring of rScO2 provided guidance on the adequacy of cerebral perfusion during selective antegrade cerebral perfusion. |

| Blas 12 | Aortic Arch Repair with DHCA INVOS™ 3100 |

Monitoring of rScO2 was useful for judging the adequacy of cerebral oxygenation during retrograde cerebral perfusion |

| Sugawara 21, | Ascending to infra-renal aortic bypass grafting combined with reconstruction of the right axillary artery TOS-96 |

Patient with Takayasu’s disease with occlusion of all aortic branches. The rScO2 was kept > 50% throughout surgery and the patient suffered no neurologic deficits. |

| Prabhune, 2002, 11957172} | CABG INVOS™ 4100 |

Monitoring of rScO2 provided early warning of O2 delivery failure to CPB oxygenator. |

| Janelle23 | AVR INVOS™ 5100 |

Monitoring of rScO2 provided an indication of aortic dissection during CPB allowing for surgical correction of the defect. |

| Kasahara Kasahara, 2007, 18292727} | MVR NIRO 200 |

Monitoring rScO2 was valuable in preventing neurological complications in patient with “porcelain” aorta and aortic regurgitation. |

| Aron 11 | CABG, MVR and Maze INVOS™ 5100 |

Reduced rScO2 saturation after separation from CPB likely indicating vasospasm in patient with Raynaud’s disease prompted vasodilator therapy with restoration of O2 saturation. |

| Cheng 13 | Aortic arch replacement INVOS™ 5100 |

Monitoring rScO2 provided feedback on the adequacy of cerebral perfusion during CPB. |

| Fujiwara 16 | Repeat MVR Not Specified |

Anaphylaxis after aprotinin administration. Persistent low rScO2 prompted immediate cardiopulmonary bypass and further resuscitatin. The patient suffered no significant neurologic deficits. |

| Paarmann Paarmann, 2010, 20576653} | Transcatheter aortic valve implantation Invos™ 5100 |

rScO2 monitoring provided guide to adequacy of CPR after cardiac arrest during aortic valve deployment. The patient was emergently placed on CPB and the aortic valve implanted. The patient recovered without a neurological deficit. |

| Hassan 17 | MVR, AVR Foresight™ |

rScO2 was used to monitor adequacy of cerebral perfusion during temporary occlusion of persistent left superior cava during surgery. |

| Vernick l22 | CABC, AVR, and and CABG Invos™ 5100 |

rScO2 monitoring provided early detection of superior vena cava obstruction. |

| Faulkner 14 | CABG, AVR, and MVR Foresight™ |

rScO2 monitoring provided early detection of superior vena cava obstruction. |

CABG=coronary artery bypass graft; AVR = aortic valve replacement; MVR = mitral valve replacement; CPB=cardiopulmonary bypass; DHCA=deep hypothermic circulatory arrest.

NIRS devices: Invos™ ( Somanetics/Covidien, Inc, Boulder, CO); Fore-Sight™( CAS Medical Systems, Branford, CN); EQUANOX™, (Nonin Medical Inc, Minneapolis, MN); CerOx™,( Ornim Medical, Lod, Isreal).

Observational Studies and Randomized Trials Reporting Secondary NIRS Endpoints

Our search identified 18 prospective observational and nine retrospective studies that included a total of 4714 patients (Table 2). We also identified two prospectively randomized studies that involved 440 patients and included NIRS endpoints.

Table 2.

Observational studies of near-infrared spectroscopy (NIRS) or other clinical trials that reported regional cerebral oxygen saturation endpoints in relation to patient outcomes

| Article | Study type/NIRS device used for monitoring | Number of subjects | Surgery type | Definition of neurologic function or other complications | Comprehensive neuropsychological testing and/or neurologic evaluation | Major findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aortic Surgery | ||||||

| Ogino68 | Prospective observational INVOS™ 3100 |

12 | Aortic arch repair | Not reported | No | NIRS monitoring is useful for detecting adequacy of cerebral perfusion. |

| Higami69 | Retrospective INVOS™ 3100 |

92 (40 retrograde cerebral perfusion; 52 selective antegrade cerebral perfusion) | Aortic arch repair | Not reported | No | rSCO2 = 57.4% in the retrograde cerebral perfusion group, 71.7% in the antegrade cerebral perfusion group. |

| Yamashita70 | Prospective observational INVOS™ 3100 |

21 (13 total arch replacement; 18 CABG/valve replacement control group) | Aortic arch replacement, CABG, valve surgery | Not reported | No | No hospital deaths or neurologic dysfunction in either group. Bilateral differences in rSCO2 between the 2 hemispheres were significantly increased during the rewarming phase of surgery. |

| Orihashi30 | Retrospective TOS-96 |

59 | Aortic arch surgery with selective cerebral perfusion | New clinical stroke or transient neurologic symptoms both confirmed with CT imaging | No | Duration of rSCO2 < 55% and <60% was longer in the 27.1% of pts who had neurologic events than in those who did not. |

| Orihashi24 | Retrospective TOS-96 |

35 | Aortic arch surgery | Not reported | No | Four of 35 pts had decreased rScO2 (1 pt had right-sided rScO2 decreased to 44% and another had bilateral rScO2 decreased to <60%) that prompted reposition/replacement of selective antegrade cerebral perfusion catheter. No adverse neurologic outcomes. |

| Orihashi71 | Retrospective TOS-96 |

75 | Femoral vs axillary artery cannulation for repair of ascending aortic dissection | Not reported | No | Right rSCO2 decreased to <55% in 1 pt with post-op speech disturbance and right frontal lobe cerebral infarction detected on CT. |

| Olsson31 | Retrospective INVOS™ 4100 |

46 | Aortic arch surgery | Stroke: new neurologic deficit that did not resolve before discharge | No | rSCO2 was lower in pts with stroke (rSCO2 decreased to 65–80% of baseline bilaterally) than in those without stroke. |

| Rubio25 | Prospective observational Invos™ |

17 (8 adults) | Aortic arch repair | Not reported | No | Decreased rScO2 (<50% = “intervention threshold”; <40% = “critical threshold”) correlated with arterial cannula malposition prompting early intervention. |

| Schön32 | Retrospective Invos™ 5100 |

51 | Aortic surgery with CPB and DHCA | Not reported | No | Two of 11 pts in the desaturation group (rScO2 < 80% of baseline) developed stroke after surgery (p = 0.043 vs pts without desaturation). |

| Schön32,72 | Retrospective Invos™ 5100 |

800 | Aortic surgery with CPB and DHCA | Not reported | No | Pts with rScO2 <50% had higher incidence of post-op organ dysfunction and longer hospital length of stay. |

| Harrer26 | Prospective observational NIRO 300 |

13 | Aortic arch surgery | Not reported | No | Twelve pts were switched from unilateral to bilateral selective antegrade perfusion based on rScO2 monitoring; rSCO2 increased to 63±5% (p < 0.001). |

| Fischer33 | Prospective observational Foresight™ |

30 | Aortic arch repair | Major complications* Minor complications# |

No | Pts with decreased rSCO2 (50%, 55%, 60%, 65%) or rSCO2 < 65% for >9 min were more likely to have major complications, prolonged mechanical lung ventilation, prolonged ICU and hospital length of stay. |

| Cardiac Surgery | ||||||

| Nollert37 | Prospective observational Not Specified |

41 | CABG and/or valve surgery | No | No | rScO2 lower in pts with decrements in MMSE after surgery (n=4). |

| Fearn62 | Prospective observational Not Specified |

70 | CABG | Not reported | Yes | Decrease in rSCO2 resulted in impaired attention 1 week after surgery. |

| Reents44 | Prospective observational INVOS™ 4100 |

47 | CABG | Decrease of >1 SD on 2 or more psychometric tests | Yes | No difference in rate of rSCO2 desaturation (>25% decrease from baseline or value <40%) between pts with and without cognitive dysfunction on post-op day 6. |

| Talpahewa29 | Prospective observational NIRO 300 |

23 | Off-pump CABG | Not reported | No | No in-hospital deaths, neurologic deficits, or myocardial infarction observed. rSCO2 decreased with heart positioning for distal CABG. |

| Yao38 | Prospective observationa INVOS™ 4100l |

101 | CABG and/or valve surgery | Decrease in MMSE from baseline by >20% 4 to 6 days after surgery or >30% decrease in ASEM 4 to 6 days after surgery | No | Pts with nadir rScO2 < 35% had higher incidence of post-op decrements in ASEM and MMSE (44% and 33%) than those with nadir rScO2 > 35% (12% and 9%, p = 0.002). AUC for rScO2 <40% for >10 min was independent predictor of MMSE and ASEM decrement (p = 0.021). |

| Goldman34 | Retrospective Invos™ 5100 |

1034 with rScO2 monitoring; 1245 historical controls without monitoring | CABG | Clinical stroke | No | Stroke rate lower in pts with rScO2 monitoring than in controls (0.97% vs 2.5%, p = 0.044). When analyzed based on baseline NYHA class, the frequencies of prolonged ventilation (6.8% vs 10.6%; p < 0.0014) and post-op hospitalization (p < 0.046) were lower in the monitored group than in the control group. |

| Talpahewa73 | Prospective observational NIRO 300 | 19 | CABG | Not reported | No | No in-hospital deaths or neurologic deficits. No late neurologic complications at follow-up. No significant changes in rScO2 in pts with/without non-neurologic complications |

| Edmonds35 | Retrospective INVOS™ 4100 |

332 | CABG | Type I injury: focal injury, stupor, or coma; Type II injury: decrease in intellectual function, memory deficit, or seizures | No | Minimum rSCO2 was significantly lower in injured pts (mean ± SD, 44 ± 11%, n= 10; p = 0.02) than in uninjured patients (54 ± 11%, n = 322). |

| Negargar27 | Patients randomized to CABG surgery with CPB or without CPB (off-pump). Control group had valve surgery. INVOS™ 4100 |

72 | CABG, valve surgery | Neurologic complications and possible cognitive decline when MMSE < 25. Definite cognitive disorder when MMSE < 20. A 20% decrease in MMSE score after surgery or scores < 20 for educated patients were also considered abnormal. | No | No difference in frequency of a decrease in rSCO2 >20% from baseline among the groups (p = 0.113). Difference in rSCO2 between the on-pump and off-pump bypass groups (p = 0.042). No relation between decrease in rSCO2 and post-op neurologic complications. |

| Hong40 | Prospective observational Invos™ 5100 |

100 | Valve repair | POCD: decrease from baseline on ≥1 of 3 tests or 20% increase from baseline in time to complete the TMT-A and GP. | No | Pts with decreased rScO2 (absolute rSCO2 < 50% or 20% decrease from baseline value for 5 min) required longer post-op hospitalization (p = 0.046). POCD was not associated with decreased rScO2 (p = 0.466). |

| de Tournay-Jetté41 | Prospective observational Invos 4100™ |

61 | CABG | Early (4–7 days) and late (1 month) POCD defined as decrease of >1 SD from baseline on ≥2 neuropsychologic tests. | Yes | Pts with rSCO2 <50% during surgery had higher rate of early POCD than did pts without rSCO2 decrement (p = 0.04). A decrease in rSCO2 >30% from baseline was associated with late POCD (p = 0.03). |

| Heringlake67 | Prospective observational Invos™ 4100 & 5100 |

1178 | CABG, valve repair, aortic arch repair, or combined surgery | Not reported | No | Mortality and morbidity were increased in pts with low baseline rSCO2 (≤51%) and who had no improvement in rSCO2 after supplemental oxygen (p = 0.0081). |

| Fudickar42 | Prospective observational NIRO™ 300 |

35 | CABG + AVR/MVR | POCD defined as decrease in test score >20% from baseline. | Yes | Frequency of POCD lower in pts with rSCO2 >80% of baseline and/or >55% absolute value during CPB than those with lowest rSCO2 (p = 0.015). |

| Schoen28 | Prospective randomized study comparing sevoflurane and propofol Invos™ 5100 |

128 | CABG | Analysis of interaction of interventions on raw cognitive test scores 2, 4, and 6 days after surgery | Yes | Thirty-four (27%) pts had rScO2 <50% during surgery. ANOVA for repeated measures showed that pts with rScO2 desaturation had worse scores than pts without desaturation. No differences were found in length of mechanical ventilation, duration of ICU stay, or major organ dysfunction between pts with and without rScO2 desaturation. |

| Schoen43 | Prospective observational Invos™ 5100 |

231 | CABG, valve repair, or combined surgery | Presence of delirium based on CAM-ICU inventory on at least 1 of first 3 days after surgery. | Yes | Decreased pre-op rSCO2 (p ≤ 0.001), older age (p ≤ 0.001), decreased MMSE scores (p ≤ 0.001), and neurologic or psychiatric disease (p ≤ 0.001), but not intraoperative rScO2 desaturation, were independent predictors of post-op delirium. |

NIRS = near-infrared spectroscopy; rScO2 = regional cerebral O2 saturation; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; pt = patient; CPB = cardiopulmonary bypass; DHCA = deep hypothermic circulatory arrest; SD = standard deviation; MMSE = Mini-Mental State Examination; ASEM = antisaccadic eye movement; AUC = area under curve; NYHA = New York Heart Association; POCD = postoperative cognitive dysfunction; TMT-A = Trail Making Test-Part A; ; AVR = aortic valve replacement; MVR = mitral valve replacement; CAM-ICU = confusion assessment method for the intensive care unit.

NIRS devices: Invos™ (Somanetics/Covidien, Inc, Boulder, CO); Fore-Sight™( CAS Medical Systems, Branford, CN); EQUANOX™, (Nonin Medical Inc, Minneapolis, MN); CerOx™,( Ornim Medical, Lod, Isreal); NIRO (Hamamatsu Photonics Ltd, Hertfordshire, UK); TOS-96 (TOSTEC Co., Tokyo, Japan. Note the NIRO and TOS-96 monitors are not available in the US

Twelve of the observational studies included patients undergoing aortic arch surgery, and one study compared femoral and axillary artery cannulation for ascending aorta dissection repair. These studies primarily evaluated the value of rScO2 monitoring for assessment of cerebral perfusion during surgery. Several authors reported that rScO2 monitoring was useful for adjusting or confirming the correct position of selective cerebral perfusion catheters during surgery.24,25 In the report by Orihashi et al.24 malposition of the selective antegrade cerebral perfusion cannula occurred in four (11%) of 35 patients and was manifest as a unilateral or bilateral decrease in rScO2 saturation. Others reported that monitoring rScO2 was beneficial for supporting decisions to switch from unilateral to bilateral antegrade cerebral perfusion in patients undergoing aortic arch surgery.26

Fifteen of the studies reported on 3472 patients undergoing coronary artery bypass graft (CABG) and/or cardiac valvular surgery. In one of these studies, patients were prospectively randomized to have surgery with or without CPB,27 and in a another study, patients were prospectively randomized to receive anesthesia with sevoflurane or propopofol.28 One study included only patients undergoing off-pump CABG surgery.29

Postoperative Stroke

Most of the studies on rScO2 monitoring during aortic arch surgery were small, and the number of strokes was too low to reliably assess any relationship between cerebral O2 desaturation and neurologic outcome. Orihashi et al.30 did report that the duration of rScO2 <55% and <60% during aortic arch surgery with selective antegrade cerebral perfusion was associated with postoperative neurologic events. Neurologic events occurred in 16 of 59 (27.1%) patients manifest as confusion (n=5), generalized seizure (n=5), anisocoria (n=4), mydriasis (n=1) and motor deficits (n=1). Evidence of stroke was found with brain CT or MRI imaging in 6 of these patients and the neurologic symptoms were described as transient. In a series of 46 patients, Olsson and Thelin31 reported that patients with postoperative stroke were more likely than those without stroke to have had a reduction in rScO2 during surgery to 65% to 85% of baseline. Schön et al.32 found that stroke after aortic arch surgery with deep hypothermic circulatory arrest was more common in patients with rScO2 <80% of baseline than in those without desaturation. In that study, 11 of 51 patients developed desaturation with rScO2 < 80% of baseline. Postoperative stroke occurred in 2 (18.1%) patients in the desaturation group but there were no strokes in the non-saturations group. Strokes were confirmed by CT brain imaging to have occurred in the hemisphere with the rScO2 desaturation. Fischer et al.33 reported that patients with reduced rScO2 during aortic arch surgery were more likely to have major organ dysfunction than those without desaturation. In that study of 30 patients, stroke occurred in 3 (10%) of patients. There was a significant relationship between area under the threshold of rScO2 and a composite outcome of severe complications for rScO2 thresholds of 60% (p=0.038) and 65% (p=0.025).

Two studies in patients undergoing cardiac surgery reported a link between decreases in rScO2 during surgery and postoperative stroke or combined type I (stroke) and type II (clinical deterioration in intellectual function, memory deficits, delirium, or seizures) neurologic injuries. After introducing a practice of rScO2 monitoring that included a treatment algorithm to maintain a patient’s rScO2 at or near baseline, Goldman et al.34 compared outcomes for 1034 patients who underwent CABG and/or valve surgery over an 18-month period with outcomes of 1245 control patients who had had similar surgery without NIRS monitoring over the previous 18 months. The stroke rate in the patients who had rScO2 monitoring was lower than that of the historical controls (0.97% vs. 2.5%, p = 0.044). The authors adjusted the findings for New York Heart Association class and whether surgery was with or without CPB. However, they did not use risk adjustment with multivariate logistic regression analysis to examine whether the use of rScO2 monitoring and an intervention was independently associated with a lower stroke rate. Further, the authors did not report compliance with the algorithm for treating reduced rScO2.

Edmonds35 reported a retrospective study of 332 patients who had undergone CABG surgery with rScO2 monitoring. In that study, 42% of patients experienced rScO2 desaturation, which was defined as a decrease from baseline of >20%. An algorithm for treating desaturation was in place. They reported that the observed frequency of type I and type II neurologic injury was less than the expected frequency estimated from the study by Roach et al.36 (3.0% vs expected 6.1%). This observation was due mostly to a reduction in type II injury. The nadir rScO2 in patients with neurologic injury (44±10) was lower than that in patients without injury (54±11, p = 0.02). Risk adjustment was not carried out to evaluate whether rScO2 values were independently associated with type I or type II neurologic injury, nor was compliance with the treatment algorithm for desaturation reported.

Postoperative Cognitive Dysfunction

Three studies that encompassed 214 cardiac surgery patients reported cognitive endpoints as assessed with the Mini-Mental Status Examination (MMSE); in one study the patients were also assessed with the antisaccadic eye movement (ASEM) test. Although Nollert et al.37 and Yao et al.38 found a link between low rScO2 and reduced MMSE, Negargar et al.27 reported that cerebral oximetry did not accurately predict postoperative neurologic complications. These studies defined desaturation at different rScO2 thresholds, and only Yao et al.38 provided a definition of what constituted a change in baseline in the MMSE or ASEM score. The ages of the patients in the studies by Nollert et al.37 (32 to 76 years) and Negargar et al.27 (mean age, 33.7±13.3 to 54.3±9.6 years) were lower than those in the study by Yao et al.38 (mean age, 66±11 years). Only Yao et al.38 performed multivariate logistic regression analysis, in which they found that area under the curve of the duration and magnitude of rScO2 <40% was an independent predictor of postoperative ASEM and MMSE impairments. Although it provides a general assessment of memory, orientation, and attention, the MMSE may be insensitive for detecting POCD.39

Investigators in six observational studies that encompassed 371 patients undergoing cardiac surgery carried out more detailed cognitive assessments with a psychometric battery in accordance with consensus statements,40 although Hong et al.40 used an abridged version of this recommended battery. Four studies did find a relationship between decrements in rScO2 from baseline and POCD,28,41–43 and two did not.40,44 The sample sizes of all six studies were small (range, 35 to 128 subjects) and they were all under-powered to exclude type II error. Furthermore, the patients in these studies were relatively young, and the threshold and/or duration of rScO2 decrement used to define significant desaturation varied. Postoperative cognitive assessments were limited to the hospitalization phase in all but one study,41 which reported cognitive results 1 month after surgery. In these studies, the definition of cognitive decline was a decrease from baseline of >1 standard deviation on two or more psychometric tests. This definition has been questioned because it does not account for correlation between tests that might result in a cognitive deficit in one domain being counted twice.45,46 In subanalysis of a randomized study that compared cognitive outcomes of patients anesthetized with sevoflurane and propofol, Schoen et al.28 used analysis of variance for repeated measures to show that patients with rScO2 desaturation had worse scores than those without desaturation.

Delirium

Several observational studies reported on postoperative delirium.26,33,43,47 Only one study provided an objective assessment for delirium by using the confusion-assessment-method for the intensive care unit inventory.43 The authors reported delirium in 62 (26.8%) of 231 patients. They found that preoperative rScO2 was lower in patients that developed postoperative delirium than in those that did not (mean±SD, 58.1% vs 63.1±7.2, p≤0.001) but that peripheral arterial oxygen saturation did not differ between the two groups. Additionally, during surgery, the area under the curve (AUC) for an rScO2 cutoff of 50% was larger (41.6±114.9 vs 19.5±94.9, p≤0.001) and the minimal rScO2 lower (48.6±9.3 vs 55.1±8.6, p≤0.001) for patients who developed delirium than for those who did not. The AUC for of the receiver operator characteristic curve for minimal intraoperative rScO2 for predicting delirium (0.73, CI: 0.66 to 0.80, p = 0.0001) showed that an rScO2 cutoff of 51% best predicted delirium (sensitivity, 60.0%; specificity, 75.6%). Based on binary logistic regression analysis, older age, lower MMSE, neurologic or psychiatric disease, and lower baseline rScO2 while breathing O2, but not intraoperative rScO2 desaturation, were independently associated with postoperative delirium.

Prospectively Randomized Intervention Trials for rScO2 Desaturation

We identified two prospectively randomized trials that evaluated interventions for correcting rScO2 desaturation during cardiac surgery (Table 3).8,9 Each trial used a similar threshold for treating decrements in rScO2. Detailed psychometric testing was carried out only in the study by Slater et al.9 In a study of 200 patients, Murkin et al.8 reported one stroke in the intervention group and four in the control group. However, that study was not powered to detect a difference in stroke rate between groups; it was powered to detect a 50% decrease in complications based on a projected complication rate of 40% in controls. The actual rate of complications, though, was only 30%, and the reduction in all complications in the intervention group decreased 23%, a value that was not statistically significant. Further, the major findings were not risk adjusted to assess whether the interventions for treating a reduction in rScO2 were independently associated with the reduction in patient morbidity or mortality. One or more episodes of desaturation occurred in 56 of 100 patients in the intervention group. Interventions corrected the desaturation with a 80.4% success rate. One intervention was needed in two patients, two interventions were needed in 10 patients, three interventions were needed in four patients, and more than three interventions were needed in 40 patients. The interventions included (efficacy in parenthesis) raising CPB flow (67%), raising mean arterial pressure (62%), normalizing PaCO2 (50%), deepening anesthesia (48%), increasing FiO2 (43%), and instituting pulsatile perfusion (17%).

Table 3.

Prospective randomized studies that evaluated the effectiveness of interventions for regional cerebral oxygen desaturation during cardiac surgery

| Article | Groups/NIRS Device Used for Monitoring | Number of subjects | Type of surgery | Endpoints | Definition of neurologic dysfunction or other complications | Comprehensive psychometric battery | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Murkin8 | Control group: blinded rSCO2 monitoring without intervention. Intervention group: rSCO2 value was kept at ≥75% of baseline. Invos™ 5100 |

200 | CABG | Major organ morbidity and mortality, ventilation time, length of ICU and hospital stay | No | No | Incidence of death, mechanical ventilation >48 h, stroke, myocardial infarction, or mediastinal re-exploration higher in controls than in intervention group (p < 0.048). Pts with major organ morbidity or mortality had lower baseline and mean rScO2, more cerebral desaturations, longer ICU length of stay, and longer postoperative hospitalization than pts without complications. |

| Slater9 | Control group: No interventions for decline in rScO2. Intervention group: protocol for treating if cerebral rSCO2 ≤ 20% of baseline. Invos™ 5100 |

240 | CABG | Postoperative complication, incidence of cognitive decline | Cognitive decline defined as a decrease of ≥1 SD in performance on ≥1 of the neuropsychologic tests | Yes | Prolonged rSCO2 desaturation associated with increased frequency of POCD and increased hospital stay. Poor compliance with protocol for treating rSCO2 desaturation precludes conclusions on protocol effectiveness. |

rScO2 = regional cerebral O2 saturation; CABG = coronary artery bypass graft; ICU = intensive care unit; pt = patient; SD = standard deviation; POCD = postoperative cognitive dysfunction

NIRS devices: Invos™ ( Somanetics/Covidien, Inc, Boulder, CO); Fore-Sight™( CAS Medical Systems, Branford, CN); EQUANOX™, (Nonin Medical Inc, Minneapolis, MN); CerOx™,( Ornim Medical, Lod, Isreal)

In their study of 240 patients, Slater et al.9 reported poor compliance with the protocol for treating rScO2 decrements during surgery. The result was similar rates of rScO2 desaturation in the intervention (30%) and control (26%) groups. They found that patients with prolonged desaturation (rScO2 > 3,000%-sec below a 50% saturation) had a higher frequency of early postoperative cognitive decline (p = 0.024) and were at higher risk for early POCD compared to those with lower desaturation scores (OR, 2.22, p = 0.024) after adjusting for other demographic and clinical variables. There was no independent relationship between POCD at 3 months after surgery and prolonged rScO2 desaturation or between randomized treatment groups.

Health Resource Utilization

Two studies have suggested a relationship between low rSCO2 and duration of mechanical lung ventilation after surgery,33,34 but a third study failed to confirm these findings.8 Seven studies reported a relationship between low rScO2 during surgery and duration of hospitalization in the intensive care unit or postoperative ward.8,9,28,33,34,40,43 However, two studies found no relationship between rSCO2 and hospital length of stay.8,34 In the study by Slater et al.,9 patients with rScO2 desaturation > 3,000%-sec had a nearly threefold increased risk for prolonged hospitalization (>6 days) compared to those without desaturation (OR, 2.71; 95% CI, 1.31 to 5.60; p = 0.007).

DISCUSSION

In this systematic review we sought to evaluate whether decrements in rScO2 from baseline were associated with stroke, POCD, and/or delirium in adult patients after cardiac or aortic surgery. While a relationship between rScO2 reductions and these outcomes have been reported, the results were not consistent. Furthermore, we found that there is no evidence currently available to support or refute the premise that interventions to correct rScO2 during surgery lead to improved neurologic outcomes.

Monitoring rScO2 with NIRS during cardiac surgery could have many potential benefits for assessing the adequacy of cerebral oxygen balance, particularly for the growing number of elderly patients undergoing surgery and for those with cerebral vascular disease that causes a predisposition to brain injury.48–50 A limitation in interpreting the existing studies that we reviewed is the variety of devices used by the different investigators and the varying definitions used to define an abnormality in rScO2. Important differences exist between NIRS monitors including in the source of light, the number of wavelengths of light emitted, and the distances between light emitting optodes and sensors. The most widely used monitors in the US are the INVOS 5100 monitor (Covidien; Boulder, CO), the FORE-SIGHT monitor (CAS Medical Systems Inc; Brandford, CT), and the the EQUANOX Classic 7600 monitor (Nonin Medical Inc; Plymouth, MN). For the INVOS monitor sensors for light detection are placed 30 mm and 40 mm from the light emitting diode, while for the FORE-SIGHT monitor the sensors are 15 mm and 50 mm from the laser generated source of light. The EQUANOX Classic 7600 monitor (Nonin Medical Inc; Plymouth, MN) system uses two sets of separate light emitting diodes and two light sensors that are separated by 20 mm and 40 mm from the light source. The latter device uses a more complex analysis process whereby the 40 mm detector for one light source serves as the proximal sensor for the other device. The CerOx monitor (Ornim Medical, Lod, Isreal) uses a laser light source and has one sensor. Unique to this monitor is the use of ultrasound to “tag” the light via the acusto-optic effect allowing for the assessment of the light penetration profile and thus focus the light on the desired depth and volume of brain tissue. Monitoring of the reflected ultrasound further provides an indicator of local tissue cerebral blood flow. Other monitors available outside the US include the NIRO-200 (Hamamatsu Photonics, Hamamatsu City, Japan) and the TOS-96 (Tostec, Tokyo, Japan). The NIRO-300 monitor uses laser light with photodetectors at a distance of 37 mm and 43 mm from the light source. The TOS-96 uses a light emitting diode with only 1 photodetector placed 40 mm from the light source.

There is no universal definition of what decrement in rScO2 from baseline constitutes an abnormal finding during cardiac surgery. Both relative decreases in rScO2 from baseline (eg, 20% decrease) and an absolute threshold rScO2 (eg, < 50%) were used in the reviewed studies. Thresholds of rScO2 values indicative of cerebral ischemia have been derived mostly from data obtained from patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy. In those studies a reduction from baseline in rScO2 ipsilateral to carotid artery clamped from 5% to 15% were found to be associated with reductions in transcranial Doppler measured cerebral blood flow velocity, slowing of the electroencephalogram (EEG), or changes in somatosensory evoked potentials (SSEP) with a sensitivity that ranges between 44% to 100% and specificity between 44% to 82%.51,52,53,54,55 In a study of 323 patients, however, 24 (7.4%) patients had discrepancies between rScO2 changes during carotid artery clamping and EEG or SSEP monitoring results.56 In that study, 7 patients had no change in rScO2 despite marked abnormalities in the EEG or SSEP while 1 patient had a reduction in rScO2 without EEG or SSEP changes. Other data from patients undergoing carotid endarteretomy under regional anesthesia found that a reduction in rScO2 of 20% from baseline identified neurologic symptoms during carotid artery clamping with a sensitivity of 80% and specificity of 82%.57 In that study rScO2 decreased from a mean of 63.2±8.1% to 51.0±11.6% (p=0.0002) in patients with neurologic symptoms. In a study of 19 patients undergoing carotid surgery, a rScO2 value during carotid clamping between 54% and 56% predicted EEG slowing.55 It is not clear whether these data can be extrapolated to patient undergoing cardiac surgery where anesthetic technique and body temperature differ than for carotid surgery.

One explanation for false negative rScO2 findings for detecting cerebral ischemia during carotid artery clamping is that interventions such as shunt placement and raising the blood pressure may have been instituted based on the other monitoring modalities before ischemia reached a critical rScO2 threshold. Another explanation might be contamination of the rScO2 reading by extracranial tissue. Many clinical NIRS monitors use algorithms for subtracting light absorption from superficial tissue from light absorption from deeper tissue to yield rScO2. This approach was validated in a study of 14 patients after the injection of the near infrared chromophore indocyanine green into the carotid artery during cerebral angiography.58 Washout curves were measured by sensors with 4 detectors that were 10, 20, 30 and 40 mm from the infrared light source on the right forehead and 15, 25, 35 and 45 mm from the light source for the left forehead. These investigators found that relative absorption increased with increasing distance of the sensor from the light source when indocyanine green was injected into the internal carotid artery but there was little attenuation of light absorption when dye was injected into the external carotid artery.. In a study of 60 patients undergoing carotid endarterectomy the contribution of intracranial versus extracranial blood source for tissue oxygenation measured with the NIRO-300 monitor were determined during selective clamping of the external carotid and internal carotid.61 These investigators found a significant correlation between changes in regional cerebral oxygenation and changes in TCD measured cerebral blood flow velocity (r=0.56, P<0.0001) during internal carotid artery clamping. There was no correlation between skin laser Doppler flow velocity and cerebral tissue oxygenation during external carotid artery clamping. Overall, the sensitivity of NIRS measured cerebral tissue oxygenation for detecting intracranial and extracranial flow changes was 87.5% and and 0%, respectively. The specificity for these measurements were 100% and 0%, respectively. These data support of the reliability of NIRS to detect changes in cerebral oxygenation.

The reliability of existing light subtraction algorithms, though, are challenged by a clinical study in patients undergoing spine surgery, where changes in rScO2 were measured during hypercapnia before and after the inflation of a pneumatic cuff circumferentially placed around the forehead.59 Inflation of the scalp tourniquet meant to induce scalp ischemia attenuated changes in rScO2 with hypercapnia. Reliable subtraction of extracranial light absorption from that measured from deeper structures should have resulted in no change in rScO2 results with scalp ischemia. A recent study in volunteers suggested that extracranial contamination of the NIRS signal may be significant but the magnitude in reduction in the rScO2 reading varies between clinically available devices.60 Whether these findings affect the reliability of rScO2 as a trend monitoring in cardiac surgical patients is not known. More importantly, there are no data that have compared the sensitivity or reliability of the various available NIRS monitors for identifying risk for adverse neurological outcomes. Thus, whether data obtained with one NIRS device can be extrapolated to another device is not known.

Our review suggests that the most pervasive information supporting the value of rScO2 monitoring is for identifying CPB cannula malposition, particularly malposition of selective antegrade cerebral perfusion catheters used for surgery of the aortic arch. These data, though, are mostly anecdotal. Given the relative infrequency of aortic surgery in most centers, obtaining enough patients for a prospective randomized trial to detect differences in rates of stroke between monitored and non-monitored patients would be difficult. Consequently, clinicians may be satisfied with less robust evidence when making decisions regarding NIRS monitoring during surgery in which the continuity of cerebral vessels may be compromised. Nonetheless, data on the specificity of rScO2 monitoring for ensuring cerebral perfusion are currently not available. That is, there is little evidence on whether the absence of acute reductions in rScO2 ensures adequate cerebral blood flow.

Several investigations have suggested a link between acute reductions in rScO2 from baseline and POCD and stroke.31,34,41–43,62 Other observational studies have suggested that a reduction in rScO2 is associated with postoperative delirium or longer stays in the intensive care unit or hospital. These reports have many limitations, including the use of insensitive cognitive assessments such as the Mini-Mental Status Examination, inadequate sample size to allow for risk adjustments with multivariate logistic regression analysis, young patient age, the use of historical controls, failure to report adherence with protocols for treating rScO2 desaturation, failure to report the approach for addressing missing data, testing only in the immediate postoperative period, and the use of analysis methods that have been suggested to be inappropriate.45,46 Inconsistencies in the definitions of rScO2 desaturation threshold and psychometric test result reporting preclude meta-analysis of these data.

We found only two prospectively randomized trials that investigated whether interventions to correct acute reductions in rScO2 improve patient outcomes. In one of those studies, poor adherence with the protocol for treating acute rScO2 reductions precluded interpretation of the results.9 However, Murkin et al.8 reported that interventions for raising rScO2 were effective in 80% of patients and that such interventions were associated with a lower frequency of the composite endpoint of death, mechanical ventilation >48 h, stroke, renal failure requiring dialysis, myocardial infarction, mediastinal re-exploration, or deep sternal wound infection compared with nonintervention (p < 0.048). That study was not powered to detect differences in stroke rate between intervention and control patients and did not use risk adjustment to assess independent relationships between the interventions for rScO2 desaturation and complications. In that study major organ morbidity was a secondary outcome of the study that occurred in 3% of patients in the intervention group and 11% of controls. Further, the direct relationship between interventions aimed at improving rScO2 and some components of the composite outcome such as myocardial infarction, bleeding, and sternal wound infections was not clearly elucidated.

Nonetheless, the data by Murkin et al8 support the view that the brain might provide an “index organ” for ensuring organ perfusion during CPB. Major organs such as the brain and kidney are normally protected from hypotension by autoregulatory vascular compensations that maintain a steady flow of oxygenated blood across a range of blood pressures. Thus, maintaining blood pressure in the autoregulatory range for the brain might ensure adequate blood pressure for renal perfusion during CPB. Our own data have shown that excursions of blood pressure below the lower limit of cerebral autoregulation determined by processing of rScO2 signals in relation to blood pressure was independently associated with risk for acute kidney injury after cardiac surgery.63 Nonetheless, experiments in piglets have shown that neurohumoral compensatory mechanisms resulting in increased systemic vascular resistance during hypotension ensures cerebral blood flow at the expense of splanchnic and renal hypoperfusion.64 In that study, renal blood flow was nearly 25% of baseline during hemorrhagic shock before cerebral blood flow was compromised. These and other data support the notion that cerebral blood flow is more dependent on blood pressure during cardiac surgery while renal blood flow maybe more dependent on cardiac output or CPB flow rate.65,66

Clinician often encounter patients with baseline rScO2 < 50% that otherwise would be considered below the threshold for cerebral ischemia. Since rScO2 is an indicator of cerebral oxygen supply versus metabolic oxygen demand, factors such as low cardiac output, pulmonary disease, cerebral vascular disease, or anemia that may reduce cerebral arterial oxygen supply result in increase oxygen extraction by the brain and resultant low rScO2. Thus, whether low rScO2 simply identifies patients with severe cardiopulmonary dysfucntion or cerebral vascular disease who are at high risk for neurologic complications, or whether it represents a potentially modifiable risk factor, is not clear. Murkin et al8 reported that baseline rScO2 was lower in patients at risk for morbidity or mortality after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. Further, in a study of 1,178 patients who underwent cardiac surgery with CPB patients who had a preoperative rScO2 < 50% while breathing oxygen were found to be at increased risk for 30-day and 1-year mortality.67 In that study, rScO2 was correlated with age, gender, body mass index, American Society of Anesthesiology grade, EuroSCORE, left ventricular ejection fraction, glomerular filtration rate, and hematocrit. Further, a rScO2 of 60% while breathing oxygen for 2 min identified adjusted risk for morbidity with a sensitivity of 56.1% and specificity of 71.4%. It is not surprising, thus, that low baseline rScO2 identifies patients at high risk for adverse events after surgery including prolonged mechanical lung ventilation, duration of hospitalization in the ICU or on the postoperative ward. 8,9,28,33,34,40,43 Our review extends the findings of Taillefer and Denault,7 who published a systematic review of the clinical efficacy of NIRS monitoring of cardiac surgery in 2005. Although they identified 48 clinical trials, 28 were published only as abstracts. Most of those abstracts have not been subsequently published as full-length manuscripts. Our review provides an update of the clinical literature related to NIRS monitoring during cardiac surgery. Nonetheless, the conclusions of Taliffer and Denault7 that only low-level clinical evidence supports NIRS use during cardiac surgery remains unchanged. The overall cost-benefit ratio of NIRS monitoring requires more rigorous research.

In conclusion, many reports in the literature suggest that reductions in rScO2 during cardiac surgery may provide an indication for mechanical mishaps related to CPB cannulas, particularly during aortic surgery, although most are ancedotal. The level of evidence linking decreased rScO2 during cardiac surgery to postoperative neurologic complications is low. Further, current evidence does not definitively show that interventions to improve rScO2 desaturation prevents stroke, delirium, or POCD.

References

- 1.Jöbsis FF. Noninvasive, infrared monitoring of cerebral and myocardial oxygen sufficiency and circulatory parameters. Science. 1977;198:1264–7. doi: 10.1126/science.929199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ferrari M, Giannini I, Sideri G, Zanette E. Continuous non invasive monitoring of human brain by near infrared spectroscopy. Adv Exp Med Biol. 1985;191:873–82. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-3291-6_88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCormick P, Stewart M, Goetting M, Dujovny M, Lewis G, Ausman J. Noninvasive cerebral optical spectroscopy for monitoring cerebral oxygen delivery and hemodynamics. Crit Care Med. 1991;19:89–97. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199101000-00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Murkin J, Arango M. Near-infrared spectroscopy as an index of brain and tissue oxygenation. Br J Anaesth. 2009;103:i3–13. doi: 10.1093/bja/aep299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim MB, Ward DS, Cartwright CR, Kolano J, Chlebowski S, Henson LC. Estimation of jugular venous O2 saturation from cerebral oximetry or arterial O2 saturation during isocapnic hypoxia. J Clin Monit Comput. 2000;16:191–9. doi: 10.1023/a:1009940031063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferrari M, Quaresima V. Near infrared brain and muscle oximetry from the discovery to current application. J Near Infrared Spectrosc. 2012;20:1–14. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Taillefer MC, Denault AY. Cerebral near-infrared spectroscopy in adult heart surgery: systematic review of its clinical efficacy. Can J Anaesth. 2005;52:79–87. doi: 10.1007/BF03018586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murkin JM, Adams SJ, Novick RJ, Quantz M, Bainbridge D, Iglesias I, Cleland A, Schaefer B, Irwin B, Fox S. Monitoring brain oxygen saturation during coronary bypass surgery: a randomized, prospective study. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:51–8. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000246814.29362.f4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Slater JP, Guarino T, Stack J, Vinod K, Bustami RT, Brown JM, 3rd, Rodriguez AL, Magovern CJ, Zaubler T, Freundlich K, Parr GV. Cerebral oxygen desaturation predicts cognitive decline and longer hospital stay after cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2009;87:36–44. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2008.08.070. discussion -5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Aono M, Sata J, Nishino T. Regional cerebral oxygen saturation as a monitor of cerebral oxygenation and perfusion during deep hypothermic circulatory arrest and selective cerebral perfusion. Masui. 1998;47:335–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aron JH, Fink GW, Swartz MF, Ford B, Hauser MC, O’Leary CE, Puskas F. Cerebral oxygen desaturation after cardiopulmonary bypass in a patient with Raynaud’s phenomenon detected by near-infrared cerebral oximetry. Anesth Analg. 2007;104:1034–6. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000260265.53212.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Blas ML, Lobato EB, Martin T. Noninvasive infrared spectroscopy as a monitor of retrograde cerebral perfusion during deep hypothermia. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1999;13:244–5. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(99)90114-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cheng HW, Chang HH, Chen YJ, Chang WK, Chan KH, Chen PT. Clinical value of application of cerebral oximetry in total replacement of the aortic arch and concomitant vessels. Acta Anaesthesiol Taiwan. 2008;46:178–83. doi: 10.1016/S1875-4597(09)60006-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Faulkner JT, Hartley M, Tang A. Using cerebral oximetry to prevent adverse outcomes during cardiac surgery. Perfusion. 2011;26:79–81. doi: 10.1177/0267659110393298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fischer GW, Stone ME. Cerebral air embolism recognized by cerebral oximetry. Semin Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2009;13:56–9. doi: 10.1177/1089253208330710. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Fujiwara Y, Matsuura S, Fukuda K. Case of aprotinin-induced anaphylactic shock. Masui. 2008;57:366–9. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hassan MA, Rozario C, Elsayed H, Morcos K, Millner R. A novel application of cerebral oximetry in cardiac surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2010;90:1700–1. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2010.04.095. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Kasahara H, Shin H, Mori M. Cerebral perfusion using the tissue oxygenation index in mitral valve repair in a patient with porcelain aorta and aortic regurgitation. Ann Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2007;13:413–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paarmann H, Heringlake M, Sier H, Schon J. The association of non-invasive cerebral and mixed venous oxygen saturation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Interact Cardiovasc Thorac Surg. 2010;11:371–3. doi: 10.1510/icvts.2010.240929. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Prabhune A, Sehic A, Spence PA, Church T, Edmonds HL., Jr Cerebral oximetry provides early warning of oxygen delivery failure during cardiopulmonary bypass. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2002;16:204–6. doi: 10.1053/jcan.2002.31069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sugawara Y, Sueda T, Orihashi K, Okada K. Surgical treatment of atypical aortic coarctation associated with occlusion of all arch vessels in Takayasu’s disease. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2002;22:836–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(02)00528-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Vernick WJ, Oware A. Early diagnosis of superior vena cava obstruction facilitated by the use of cerebral oximetry. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011;25:1101–3. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.08.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janelle GMS, Gravenstein N, Martin T, Urdaneta F. Unilateral cerebral oxygen desaturation during emergent repair of a DeBakey type 1 aortic dissection: Potential aversion of a major catastrophe. Anesthesiology. 2002;96:1263–5. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200205000-00033. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Orihashi K, Sueda T, Okada K, Imai K. Malposition of selective cerebral perfusion catheter is not a rare event. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2005;27:644–8. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.12.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Rubio A, Hakami L, Munch F, Tandler R, Harig F, Weyand M. Noninvasive control of adequate cerebral oxygenation during low-flow antegrade selective cerebral perfusion on adults and infants in the aortic arch surgery. J Card Surg. 2008;23:474–9. doi: 10.1111/j.1540-8191.2008.00644.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Harrer M, Waldenberger FR, Weiss G, Folkmann S, Gorlitzer M, Moidl R, Grabenwoeger M. Aortic arch surgery using bilateral antegrade selective cerebral perfusion in combination with near-infrared spectroscopy. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2010;38:561–7. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2010.03.016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Negargar S, Mahmoudpour A, Taheri R, Sanaie S. The relationship between cerebral oxygen saturation changes and postopoerative neurologic complications in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Pak J Med Sci. 2007;23:380–5. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Schoen J, Husemann L, Tiemeyer C, Lueloh A, Sedemund-Adib B, Berger KU, Hueppe M, Heringlake M. Cognitive function after sevoflurane- vs propofol-based anaesthesia for on-pump cardiac surgery: a randomized controlled trial. Br J Anaesth. 2011;106:840–50. doi: 10.1093/bja/aer091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Talpahewa SP, Ascione R, Angelini GD, Lovell AT. Cerebral cortical oxygenation changes during OPCAB surgery. Ann Thorac Surg. 2003;76:1516–22. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(03)01072-5. discussion 22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Orihashi K, Sueda T, Okada K, Imai K. Near-infrared spectroscopy for monitoring cerebral ischemia during selective cerebral perfusion. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:907–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Olsson C, Thelin S. Regional cerebral saturation monitoring with near-infrared spectroscopy during selective antegrade cerebral perfusion: diagnostic performance and relationship to postoperative stroke. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:371–9. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.08.068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Schön J, Serien V, Heinze H, Hanke T, Bechtel M, Eleftheriadis S, Groesdonk H-V, Dübener L, Heringlake M. Association between cerebral desaturation and an increased risk of stroke in patients undergoing deep hypothermic circulatory arrest for cardiothoracic surgery. Appl Cardiopulm Pathophysiol. 2009;13:201–7. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Fischer GW, Lin HM, Krol M, Galati MF, Di Luozzo G, Griepp RB, Reich DL. Noninvasive cerebral oxygenation may predict outcome in patients undergoing aortic arch surgery. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2011;141:815–21. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2010.05.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Goldman S, Sutter F, Ferdinand F, Trace C. Optimizing intraoperative cerebral oxygen delivery using noninvasive cerebral oximetry decreases the incidence of stroke for cardiac surgical patients. Heart Surg Forum. 2004;7:E376–81. doi: 10.1532/HSF98.20041062. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Edmonds HL., Jr Protective effect of neuromonitoring during cardiac surgery. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2005;1053:12–9. doi: 10.1196/annals.1344.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Roach GW, Kanchuger M, Mangano CM, Newman M, Nussmeier N, Wolman R, Aggarwal A, Marschall K, Graham SH, Ley C. Adverse cerebral outcomes after coronary bypass surgery. Multicenter Study of Perioperative Ischemia Research Group and the Ischemia Research and Education Foundation Investigators. N Engl J Med. 1996;335:1857–63. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199612193352501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nollert G, Mohnle P, Tassani-Prell P, Uttner I, Borasio GD, Schmoeckel M, Reichart B. Postoperative neuropsychological dysfunction and cerebral oxygenation during cardiac surgery. Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 1995;43:260–4. doi: 10.1055/s-2007-1013224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Yao FS, Tseng CC, Ho CY, Levin SK, Illner P. Cerebral oxygen desaturation is associated with early postoperative neuropsychological dysfunction in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2004;18:552–8. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2004.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Anthony JC, LeResche L, Niaz U, von Korff MR, Folstein MF. Limits of the ‘Mini-Mental State’ as a screening test for dementia and delirium among hospital patients. Psychol Med. 1982;12:397–408. doi: 10.1017/s0033291700046730. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hong SW, Shim JK, Choi YS, Kim DH, Chang BC, Kwak YL. Prediction of cognitive dysfunction and patients’ outcome following valvular heart surgery and the role of cerebral oximetry. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2008;33:560–5. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2008.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Tournay-Jette E, Dupuis G, Bherer L, Deschamps A, Cartier R, Denault A. The relationship between cerebral oxygen saturation changes and postoperative cognitive dysfunction in elderly patients after coronary artery bypass graft surgery. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2011;25:95–104. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2010.03.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Fudickar A, Peters S, Stapelfeldt C, Serocki G, Leiendecker J, Meybohm P, Steinfath M, Bein B. Postoperative cognitive deficit after cardiopulmonary bypass with preserved cerebral oxygenation: a prospective observational pilot study. BMC Anesthesiol. 2011;11:7. doi: 10.1186/1471-2253-11-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schoen J, Meyerrose J, Paarmann H, Heringlake M, Hueppe M, Berger KU. Preoperative regional cerebral oxygen saturation is a predictor of postoperative delirium in on-pump cardiac surgery patients: a prospective observational trial. Crit Care. 2011;15:R218. doi: 10.1186/cc10454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Reents W, Muellges W, Franke D, Babin-Ebell J, Elert O. Cerebral oxygen saturation assessed by near-infrared spectroscopy during coronary artery bypass grafting and early postoperative cognitive function. Ann Thorac Surg. 2002;74:109–14. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(02)03618-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Newman MF, Kirchner JL, Phillips-Bute B, Gaver V, Grocott H, Jones RH, Mark DB, Reves JG, Blumenthal JA. Longitudinal assessment of neurocognitive function after coronary-artery bypass surgery. N Engl J Med. 2001;344:395–402. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200102083440601. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Selnes OA, Pham L, Zeger S, McKhann GM. Defining cognitive change after CABG: decline versus normal variability. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006;82:388–90. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2006.02.060. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Liu N, Sun LZ, Chang Q, Yang JG. Clinical application of cerebral oxygenation monitoring during aortic aneurysm operation. Zhonghua Yi Xue Za Zhi. 2007;87:1030–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.ElBardissi AW, Aranki SF, Sheng S, O’Brien SM, Greenberg CC, Gammie JS. Trends in isolated coronary artery bypass grafting: an analysis of the Society of Thoracic Surgeons adult cardiac surgery database. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2012;143:273–81. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2011.10.029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Gottesman RF, Sherman PM, Grega MA, Yousem DM, Borowicz LM, Jr, Selnes OA, Baumgartner WA, McKhann GM. Watershed strokes after cardiac surgery: diagnosis, etiology, and outcome. Stroke. 2006;37:2306–11. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000236024.68020.3a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Moraca R, Lin E, Holmes JHt, Fordyce D, Campbell W, Ditkoff M, Hill M, Guyton S, Paull D, Hall RA. Impaired baseline regional cerebral perfusion in patients referred for coronary artery bypass. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2006;131:540–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jtcvs.2005.10.046. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.de Letter JA, Sie HT, Thomas BM, Moll FL, Algra A, Eikelboom BC, Ackerstaff RG. Near-infrared reflected spectroscopy and electroencephalography during carotid endarterectomy--in search of a new shunt criterion. Neurol Res. 1998;20 (Suppl 1):S23–7. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1998.11740604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Beese U, Langer H, Lang W, Dinkel M. Comparison of near-infrared spectroscopy and somatosensory evoked potentials for the detection of cerebral ischemia during carotid endarterectomy. Stroke. 1998;29:2032–7. doi: 10.1161/01.str.29.10.2032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Grubhofer G, Plochl W, Skolka M, Czerny M, Ehrlich M, Lassnigg A. Comparing Doppler ultrasonography and cerebral oximetry as indicators for shunting in carotid endarterectomy. Anesth Analg. 2000;91:1339–44. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200012000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rigamonti A, Scandroglio M, Minicucci F, Magrin S, Carozzo A, Casati A. A clinical evaluation of near-infrared cerebral oximetry in the awake patient to monitor cerebral perfusion during carotid endarterectomy. J Clin Anesth. 2005;17:426–30. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinane.2004.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hirofumi O, Otone E, Hiroshi I, Satosi I, Shigeo I, Yasuhiro N, Masato S. The effectiveness of regional cerebral oxygen saturation monitoring using near-infrared spectroscopy in carotid endarterectomy. J Clin Neurosci. 2003;10:79–83. doi: 10.1016/s0967-5868(02)00268-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Friedell ML, Clark JM, Graham DA, Isley MR, Zhang XF. Cerebral oximetry does not correlate with electroencephalography and somatosensory evoked potentials in determining the need for shunting during carotid endarterectomy. J Vasc Surg. 2008;48:601–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jvs.2008.04.065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Samra S, Dy E, Welch K, Dorje P, Zelenock G, Stanley J. Evaluation of a cerebral oximeter as a monitor of cerebral ischemia during carotid endarterectomy. Anesthesiology. 2000;93:964–70. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200010000-00015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Hongo K, Kobayashi S, Okudera H, Hokama M, Nakagawa F. Noninvasive cerebral optical spectroscopy: depth-resolved measurements of cerebral haemodynamics using indocyanine green. Neurol Res. 1995;17:89–93. doi: 10.1080/01616412.1995.11740293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Germon TJ, Young AE, Manara AR, Nelson RJ. Extracerebral absorption of near infrared light influences the detection of increased cerebral oxygenation monitored by near infrared spectroscopy. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1995;58:477–9. doi: 10.1136/jnnp.58.4.477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Davie SN, Grocott HP. Impact of extracranial contamination on regional cerebral oxygen saturation: a comparison of three cerebral oximetry technologies. Anesthesiology. 2012;116:834–40. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e31824c00d7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Al-Rawi PG, Smielewski P, Kirkpatrick PJ. Evaluation of a near-infrared spectrometer (NIRO 300) for the detection of intracranial oxygenation changes in the adult head. Stroke. 2001;32:2492–500. doi: 10.1161/hs1101.098356. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Fearn SJ, Pole R, Wesnes K, Faragher EB, Hooper TL, McCollum CN. Cerebral injury during cardiopulmonary bypass: emboli impair memory. J Thorac Cardiovasc Surg. 2001;121:1150–60. doi: 10.1067/mtc.2001.114099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Ono M, Arnaoutakis GJ, Fine DM, Brady K, Easley RB, Zheng Y, Brown C, Katz NM, Grams ME, Hogue CW. Blood pressure excursions below the cerebral autoregulation threshold during cardiac surgery are associated with risk for acute kidney injury. Crit Care Med. 2012 doi: 10.1097/CCM.0b013e31826ab3a1. in press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Rhee CJ, Kibler KK, Easley RB, Andropoulos DB, Czosnyka M, Smielewski P, Brady KM. Renovascular reactivity measured by near-infrared spectroscopy. J Appl Physiol. 2012;113:307–14. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00024.2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Schwartz AE, Kaplon RJ, Young WL, Sistino JJ, Kwiatkowski P, Michler RE. Cerebral blood flow during low-flow hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass in baboons. Anesthesiology. 1994;81:959–64. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199410000-00023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Cook DJ, Proper JA, Orszulak TA, Daly RC, Oliver WC., Jr Effect of pump flow rate on cerebral blood flow during hypothermic cardiopulmonary bypass in adults. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 1997;11:415–9. doi: 10.1016/s1053-0770(97)90047-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Heringlake M, Garbers C, Kabler JH, Anderson I, Heinze H, Schon J, Berger KU, Dibbelt L, Sievers HH, Hanke T. Preoperative cerebral oxygen saturation and clinical outcomes in cardiac surgery. Anesthesiology. 2011;114:58–69. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fef34e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Ogino H, Ueda Y, Sugita T, Morioka K, Sakakibara Y, Matsubayashi K, Nomoto T. Monitoring of regional cerebral oxygenation by near-infrared spectroscopy during continuous retrograde cerebral perfusion for aortic arch surgery. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 1998;14:415–8. doi: 10.1016/s1010-7940(98)00177-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Higami T, Kozawa S, Asada T, Obo H, Gan K, Iwahashi K, Nohara H. Retrograde cerebral perfusion versus selective cerebral perfusion as evaluated by cerebral oxygen saturation during aortic arch reconstruction. Ann Thorac Surg. 1999;67:1091–6. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(99)00135-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Yamashita K, Kazui T, Terada H, Washiyama N, Suzuki K, Bashar AH. Cerebral oxygenation monitoring for total arch replacement using selective cerebral perfusion. Ann Thorac Surg. 2001;72:503–8. doi: 10.1016/s0003-4975(01)02691-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Orihashi K, Sueda T, Okada K, Imai K. Detection and monitoring of complications associated with femoral or axillary arterial cannulation for surgical repair of aortic dissection. J Cardiothorac Vasc Anesth. 2006;20:20–5. doi: 10.1053/j.jvca.2005.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Schön J, Serien V, Hanke T, Bechtel M, Heinze H, Groesdonk H-V, Sedemund-Adib B, Berger KU, Eleftheriadis S, Heringlake M. Cerebral oxygen saturation monitoring in on-pump cardiac surgery -- a 1 year experience. Appl Cardiopulm Pathophysiol. 2009;13:243–52. [Google Scholar]

- 73.Talpahewa SP, Lovell AT, Angelini GD, Ascione R. Effect of cardiopulmonary bypass on cortical cerebral oxygenation during coronary artery bypass grafting. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2004;26:676–81. doi: 10.1016/j.ejcts.2004.06.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]