Abstract

Background

Adult height has been positively associated with prostate cancer risk. However, the exposure window of importance is currently unknown and assessments of height during earlier growth periods are scarce. In addition, the association between birth weight and prostate cancer remains undetermined. We assessed these relationships a cohort of the Copenhagen School Health Records Register (CSHRR).

Methods

The CSHRR comprises 372,636 school children. For boys born between the 1930’s and 1969, birth weight and annual childhood heights—measured between ages 7 and 13 years—were analyzed in relation to prostate cancer risk. Cox proportional hazards regression models were used to estimate hazard ratios (HR) and 95 percent confidence intervals (95%CI).

Results

There were 125,211 males for analysis, 2,987 of who were subsequently diagnosed with prostate cancer during 2.57 million person-years of follow-up. Height z-score was significantly associated with prostate cancer risk at all ages (HR~1.13). Height at age 13 years was more important than height change (p=0.024) and height at age 7 years (p=0.024), when estimates from mutually adjusted models were compared. Adjustment of birth weight did not alter estimates ascertained. Birth weight was not associated with prostate cancer risk.

Conclusions

The association between childhood height and prostate cancer risk was driven by height at age 13 years.

Impact

Our findings implicate late childhood, adolescence and adulthood growth periods as containing the exposure window(s) of interest that underlies the association between height and prostate cancer. The causal factor may not be singular given the complexity of both human growth and carcinogenesis.

Keywords: prostate neoplasms, body height, growth, body weights and measures, birth weight, cohort studies

Introduction

Consistently associated risk factors for prostate cancer are limited to age, race/ethnicity (1), family history of prostate cancer (2), country of origin/residence (3), and certain genetic polymorphisms (4). The lack of risk factors found to be associated with prostate cancer may primarily be attributable to two causes: age at exposure and the prostate-specific antigen (PSA) test. Age at exposure refers to the fact that development of the prostate organ is a life-long process, starting in utero, with morphogenesis continuing in infancy and childhood, before undergoing dramatic changes during puberty to form the adult prostate (5–8). However, most previous studies have only assessed adult exposures, given the time, financial and technical hurdles of using a life-course approach (9). Exposures with carcinogenic potential experienced during development of the prostate organ may be integral to the development of prostate cancer many years later.

PSA screening is understood to have led to significant overdiagnosis (10, 11), with a concomitant shift to earlier grades and stages of disease (12–14). This may have altered the composition of prostate cancer populations under study leading to heterogeneous results, as well as dilution of potentially identifiable risk factors associated with clinically relevant (symptomatic and/or causing death) disease, given that more than 60% of men by age 80 years are expected to harbor latent prostate cancer (15–18).

Adult height, used as a proxy of a multitude of exposures associated with infant, childhood and adolescent growth (19), has been associated with prostate cancer risk (20, 21). However, the time window (age) of importance which underlies this association is currently unknown—one previous study was able to assess childhood height (ages 2–14 years) and found indications of an increased risk for prostate cancer, although this was not statistically significant and the confidence interval was wide (odds ratio (OR)per standard deviation of height z-score=1.10; 95%CI: 0.80, 1.51). In addition, this study was unable to look at age-specific heights due to the accrual of just 33 prostate cancer outcomes (22). There is only tentative evidence for a positive association between birth weight and prostate cancer risk (23–31), but most of these analyses have been based on a small number of outcomes. The Copenhagen School Health Records Register (CSHRR) provided us with an opportunity to overcome many of the limitations of previous studies. This cohort is comprised of more than 370,000 school children from Copenhagen, Denmark, who were born from 1930 onwards. The CSHRR cohort enabled us to conduct a comprehensive analysis of childhood anthropometric measures in relation to future prostate cancer risk.

Materials and Methods

Cohort for analysis

The CSHRR has been described in detail previously (32). Briefly, the CSHRR includes 372,636 school children who ever attended school in the municipality of Copenhagen, Denmark. As part of school-based health care, annual assessments of each child resulted in a huge number of hand-written records, components of which have subsequently been computerized for individuals born 1930–1989, and more recent years continue to be added. Throughout this time period, childhood height was measured by a school physician or nurse, without the child wearing shoes, using equipment provided by the school health service. Birth weight was reported by the parent(s) at the first school health examination, with memory aided by a request for parents to bring written documentation of such values taken at, or near, the time of birth.

Over the long period covered by the CSHRR, ages of compulsory education have varied for both starting (5–7 years) and ending (13–16 years) one’s formal education. For analyses of this cohort with prostate cancer as the outcome, we have restricted the dataset to birth cohorts 1930–1969, as there were no recorded cases of prostate cancer in birth cohorts subsequent to this period given the current young ages of such men. Related to this point, we restricted the lower bound for the age at outcome (prostate cancer diagnosis) as 40 years. Assessment of childhood height was restricted to ages 7 through 13 years, as these were the predominant ages for which this information was available for this analytic cohort. Analyses of birth weight as the primary exposure, or as a covariate in the childhood height models, were undertaken on a sub-cohort (Supplementary Figure 1) given the fact that birth weight was only recorded for individuals born from 1936 onwards. Individuals with birth weights <2 kg (n=1287) or >5.5 kg (n=370) were excluded given that these weights are unlikely to be accurate.

Data linkage

In 1968 The Danish Central Office of Civil Registration (Det Centrale Person Register) assigned a personal identification number, known as the central person registration number (CPR number), to every citizen (33). Children attending school in 1968, and thereafter, had the CPR number recorded on their health card. For health cards completed prior to 1968, forename(s), surname, sex and date of birth were used to match health cards with CPR numbers. CPR numbers were successfully identified for 329,968 (89%) of the 372,636 children in the CHSRR. Individuals who died or emigrated before 1968 were never assigned a CPR number, thus precluding matching. This will not have affected the analyses presented herein because of the age distribution of prostate cancer and the lower age limit of cancer diagnosis for inclusion (40 years).

The CPR number enables linkage to a large number of other databases including the Danish Cancer Registry (34) and the Central Person Register (vital statistics) which, for this analysis, were used to provide outcome information on prostate cancer until the last date of follow-up of 31st December 2010. Prostate cancer was defined using code C61 of the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) 10th revision (35).

Statistical analysis

Age-specific childhood heights have dramatically increased over the analytic period spanned by the CSHRR, a phenomenon generally ascribed to perinatal environmental exposures (36). In addition, height obviously increases with age during childhood. To account for both of these factors in our analyses, we calculated childhood height z-scores by age (per month) with five-year birth cohorts (1930–1934, 1935–1939,…, 1965–1969) as the reference. We used the entire cohort (i.e., boys with and boys without CPR numbers) as an internal reference and the LMS method (37) to generate these z-scores. To obtain childhood height z-scores at the exact ages (i.e., 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12 or 13 years) we used the z-score if measured at the exact age (i.e., on an individual’s birthday); interpolated the z-score if the exact age measurement was not available but a measurement either side of the exact age (±12 months) were available; or extrapolated the z-score if the exact age measurement was not available and only a measurement one side of the exact age (±12 months) was available. In the absence of an exact age measurement and at least one measurement within 12 months of the exact age under scrutiny for an individual, a z-score was not generated for that age and the individual was omitted from the analysis for that age only. Given that birth weight was stable over calendar time and was normally distributed (38), birth weight z-scores were calculated in the standard way.

We calculated the mean, standard deviation, and median of birth weight and of childhood height for each age by birth cohort (five-year intervals). For the outcome of prostate cancer, we tabulated the distribution of cases, person-years and incidence rate per 100,000 by age (five-year intervals) and birth cohort (five-year intervals). For assessment of age-specific childhood height and birth weight in relation to the subsequent risk of prostate cancer in adulthood, we conducted Cox proportional hazards regression models using age as the underlying time metric with the baseline hazard stratified by birth cohort (five-year intervals). Follow-up began at age 40 years. The outcome was prostate cancer while right-censoring variables included date of death, emigration, loss to follow-up or 31st December 2010, whichever occurred first. We also assessed whether these relationships differed by pre- and post-PSA era, the cut-point for which was set as 1st January 1998 given that The Danish Society of Urology recommended PSA testing in November 1997 (39). These sensitivity analyses were restricted to men aged 40–68 years at prostate cancer diagnosis, due to the fact that 68 years was the oldest age at diagnosis available for individuals diagnosed in the pre-PSA era.

The proportional hazards assumption was tested for each age of anthropometric assessment (height and birth weight) by: 1) estimating the magnitude and statistical significance of a time (age) varying z-score effect on prostate cancer using a Cox proportional hazards regression model; 2) estimating the relationship between z-score and prostate cancer stratified into quartiles of age with calculation of a global p value for statistically significant differences between strata; 3) through visual assessment of cumulative hazard versus cumulative hazard plots of one z-score category versus another, a straight line indicates proportional hazards, while inflections indicate non-proportional hazards.

We also assessed the shape of the associations between anthropometric z-scores and prostate cancer risk by: 1) testing for linearity compared with a categorical alternative; 2) examining linear splines with 3 cut-points with a Wald test of the hypothesis that all three changes in the hazard ratio (HR) are equal to 1 (that the association is log-linear); 3) visual inspection of restricted cubic spline plots with a test against the linear alternative.

We assessed whether relationships between anthropometric z-scores and prostate cancer risk were modified by birth cohort through stratified analyses with use of a global test comparing the HRs of all strata. We also assessed whether adjusting for birth weight affected the association between childhood height and prostate cancer risk.

In order to assess whether changes in height during childhood growth were important for prostate cancer risk, we conducted Cox proportional hazards regression models that contained height z-score change between ages 7 and 13 years as well as height z-score at age 7 years or height z-score at age 13 years. Therefore, to test whether change in height z-score, height z-score at age 7 years, or height z-score at age 13 years was more important, we used the Wald test to directly compare these estimates.

Results

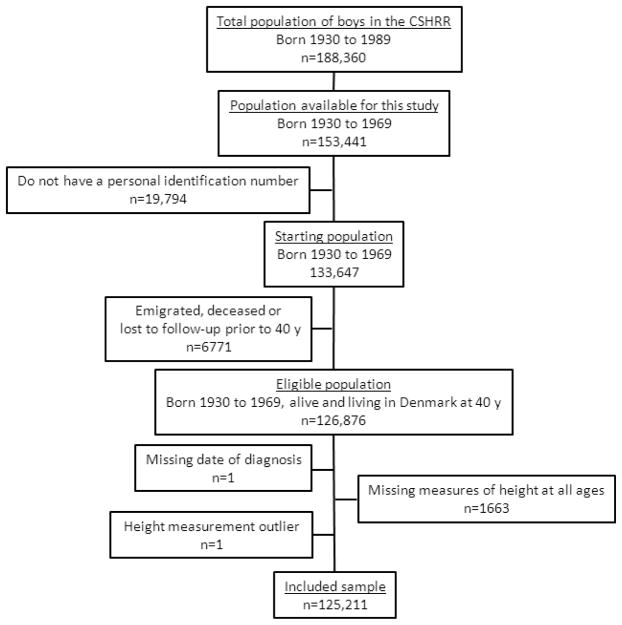

For analyses of childhood height, there were 188,360 potentially eligible boys in the CSHRR born between 1930 and 1989 (Figure 1). Of these, 34,919 were born prior to 1970 and 133,647 (87%) were linked to a CPR number. We excluded 6,771 individuals who had emigrated (n=2778), died (n=3888) or who were lost to follow-up (n=105) prior to age 40 years, 1,663 individuals who were missing height measures at all ages (7–13 years), one individual who was missing date of diagnosis of a recorded prostate cancer, and one individual who had outlying height z-scores at all ages (<−4.5 or >4.5). There remained 125,211 individuals in the cohort for analyses of childhood height. For analyses that included birth weight, there were fewer eligible boys (n=107,636, Supplementary Figure 1) due to the fact that birth weight was only collected from the birth year 1936 onwards. After exclusions, there were 93,625 individuals in the cohort for analyses of birth weight.

Figure 1.

Flow chart of eligible and included subjects in the analysis of childhood height

Mean height increased with age and with birth cohort (Supplementary Table 1). For example, mean height for the latest birth cohort (1965–1969) increased from 123.7 cm for boys aged 7 years to 156.2 cm for boys aged 13 years. For boys aged 13 years, height increased from 149.8 cm in the 1930–1934 birth cohort to 156.2 cm in the 1965–1969 birth cohort. Mean and median birth weight did not vary by birth cohort over the period assessed.

Prostate cancer counts, person-years and incidence rates by age and birth cohort are shown in Table 1. There were a total of 2,987 prostate cancers and 2.57 million person-years of follow-up. Age and birth cohort effects can be seen in the table. For example, the incidence rate increased with age in the 1930–1934 birth cohort from 20 per 100,000 person-years for the age-group 50–54 years to 1770 per 100,000 person-years for the age-group 80–84 years. For the age-group 65–69 years, prostate cancer incidence increased from 330 to 895 per 100,000 person-years for the birth cohorts 1930–1934 and 1945–1949, respectively. The overall distribution of cases by age (Supplementary Figure 2) and incidence rate by age (Supplementary Figure 3) presented expected patterns.

Table 1.

Number of cases and person-years, and crude incidence rate of prostate cancer by age (five-year intervals) and birth cohort (five-year intervals)

| Age (years) | Characteristics | Birth cohort

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1930–1934 | 1935–1939 | 1940–1944 | 1945–1949 | 1950–1954 | 1955–1959 | 1960–1964 | 1965–1969 | ||

| 40–44 | Cases (n) | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 70,116 | 92,493 | 108,792 | 108,790 | 78,099 | 64,401 | 50,995 | 32,808 | |

| IR per 100,000 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| 45–49 | Cases (n) | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 5 | 6 | 0 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 68,254 | 90,214 | 106,225 | 106,257 | 76,020 | 62,616 | 34,357 | 995 | |

| IR per 100,000 | - | - | - | - | - | 8 | 17 | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| 50–54 | Cases (n) | 13 | 8 | 20 | 24 | 32 | 17 | 0 | 0 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 65,498 | 86,906 | 102,581 | 102,511 | 72,966 | 42,371 | 1,082 | 0 | |

| IR per 100,000 | 20 | 9 | 20 | 23 | 44 | 40 | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| 55–59 | Cases (n) | 30 | 42 | 75 | 124 | 72 | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 61,440 | 82,269 | 97,365 | 97,366 | 48,516 | 1,316 | 0 | 0 | |

| IR per 100,000 | 49 | 51 | 77 | 127 | 148 | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| 60–65 | Cases (n) | 75 | 128 | 281 | 249 | 2 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 55,624 | 75,822 | 89,707 | 64,413 | 1,576 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| IR per 100,000 | 135 | 169 | 313 | 387 | - | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| 65–69 | Cases (n) | 159 | 379 | 350 | 17 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 48,178 | 66,894 | 52,864 | 1,898 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| IR per 100,000 | 330 | 567 | 662 | 895 | - | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| 70–74 | Cases (n) | 308 | 335 | 8 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 39,430 | 37,699 | 1,325 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| IR per 100,000 | 781 | 889 | 604 | - | - | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| 75–79 | Cases (n) | 201 | 11 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 19,637 | 885 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| IR per 100,000 | 1,024 | 1,243 | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

|

| |||||||||

| 80–84 | Cases (n) | 6 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| P-Y of follow-up | 339 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| IR per 100,000 | 1,770 | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | |

Abbreviations: P-Y= person-years, IR=incidence rate

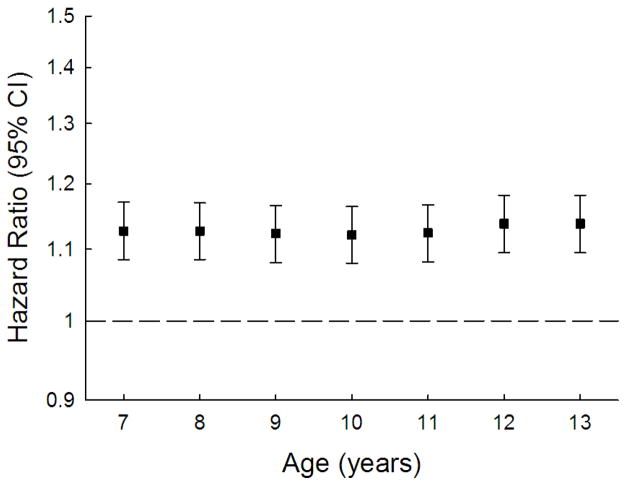

Table 2 and Figure 2 display the results of the Cox proportional hazards regression models for age-specific heights and birth weight. The hazard ratio per height z-score was approximately 1.13 and this was remarkably stable across the ages at which height was assessed as well as being statistically significant for all of them. The height z-scores are birth cohort specific, but moving from a z-score of 0 to a z-score of 1 corresponds to ~5.2 cm at age 7 years and ranged from 7.5 to 8.2 cm at age 13 years—the change in the magnitude of the z-score with age represents greater variation in height with age due to how growth occurs during childhood. The correlation coefficient between height z-score at age 7 years and age 13 years was 0.87. Birth weight showed a positive association with future prostate cancer risk, but the estimate was not statistically significant. We also provide these analyses on the raw scale should these be of use for future comparisons/meta-analyses (Supplementary Table 2).

Table 2.

Hazard ratios of prostate cancer in adulthood per increase in birth weight z-score or age-specific height z-score.

| Age (years) | N | Cases | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Birth) | 93,625 | 1,699 | 1.035 (0.982, 1.091) |

| 7 | 118,090 | 2,774 | 1.127 (1.085, 1.171) |

| 8 | 120,380 | 2,825 | 1.127 (1.085, 1.170) |

| 9 | 120,185 | 2,829 | 1.123 (1.081, 1.166) |

| 10 | 120,075 | 2,818 | 1.121 (1.080, 1.164) |

| 11 | 120,089 | 2,826 | 1.124 (1.082, 1.167) |

| 12 | 119,561 | 2,792 | 1.138 (1.095, 1.182) |

| 13 | 118,395 | 2,734 | 1.138 (1.095, 1.182) |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. All Cox regressions used age as the underlying time metric and were stratified by birth cohort.

Figure 2.

Hazard ratios of prostate cancer per unit increase in age-specific height z-score.

All Cox regressions used age as the underlying time metric and were stratified by birth cohort.

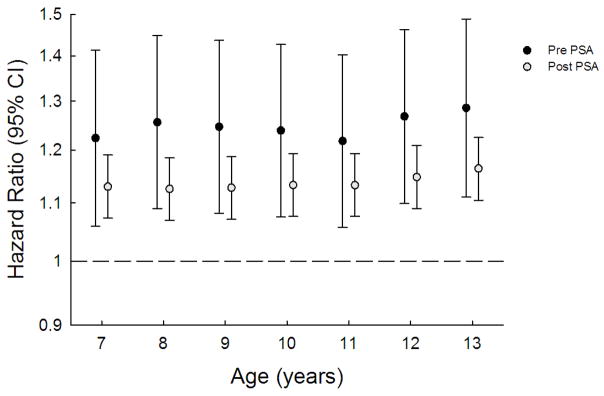

When these analyses were stratified by pre- and post-PSA era, there was tentative evidence that the associations were stronger for individuals diagnosed in the pre-PSA era (Figure 3). Although none of these comparisons were statistically significant (p<0.05), these analyses had limited statistical power given relatively small numbers of prostate cancers available for the pre-PSA era (n=212). There was no evidence that birth weight associations differed by PSA era (pre-PSA era HR=1.018, 95%CI:0.757, 1.370; post-PSA era HR=1.036, 95%CI:0.981, 1.092).

Figure 3.

Hazard ratios of prostate cancer at ages 40–68y per unit increase in age-specific height z-score stratified by PSA era.

All Cox regressions used age as the underlying time metric and were stratified by birth cohort. Pre PSA refers to the calendar period preceding 1998, whereas post PSA refers to the period 1st January 1998 onwards.

In our assessments of the proportional hazards assumption, there was little evidence of violation for either childhood height or birth weight (Supplementary Tables 3 & 4). Analyses investigating the shapes of the associations between anthropometric z-scores and prostate cancer risk indicated that these relationships were all linear. Categorical estimates for childhood height assessed at ages 7 and 13 years, as well as birth weight, are shown in Table 3; none of the tests for departure from linearity, compared with a categorical alternative or compared with spline models (Supplementary Figure 4), were statistically significant (data not shown).

Table 3.

Hazard ratios of prostate cancer by categories of birth weight z-score and age-specific height z-scores.

| Age (years) | Category of birth weight or height z-score | Total Population | Cases | Hazard Ratio (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 (Birth) | −4.5 to −1.28 | 6,527 | 113 | 1.053 (0.867, 1.280) |

| −1.28 to −0.68 | 7,921 | 120 | 1.059 (0.876, 1.280) | |

| −0.68 to 0.68 | 56,108 | 998 | referent | |

| 0.68 to 1.28 | 14,864 | 298 | 1.123 (0.987, 1.278) | |

| 1.28 to 4.5 | 8,205 | 170 | 1.072 (0.911, 1.262) | |

|

| ||||

| 7 | −4.5 to −1.28 | 12,278 | 205 | 0.738 (0.637, 0.854) |

| −1.28 to −0.68 | 18,545 | 392 | 0.883 (0.790, 0.987) | |

| −0.68 to 0.68 | 60,104 | 1,438 | referent | |

| 0.68 to 1.28 | 16,325 | 422 | 1.049 (0.941, 1.169) | |

| 1.28 to 4.5 | 10,838 | 317 | 1.230 (1.089, 1.389) | |

|

| ||||

| 13 | −4.5 to −1.28 | 11,762 | 219 | 0.836 (0.725, 0.964) |

| −1.28 to −0.68 | 18,062 | 345 | 0.818 (0.727, 0.921) | |

| −0.68 to 0.68 | 60,126 | 1,400 | referent | |

| 0.68 to 1.28 | 16,923 | 444 | 1.134 (1.019, 1.262) | |

| 1.28 to 4.5 | 11,522 | 326 | 1.255 (1.112, 1.415) | |

Abbreviation: CI, confidence interval. All Cox regressions used age as the underlying time metric and were stratified by birth cohort.

From analyses stratified by birth cohort, there was no evidence that the relationships between childhood height, birth weight and prostate cancer risk deviated, and thus the risk appears to be constant across birth cohorts (data not shown). Adjustment of birth weight in the childhood height–prostate cancer model had negligible effect on the estimates ascertained (Supplementary Table 5).

When height z-score change between ages 7 and 13 years was modeled with height z-score at age 7 years, the difference in the estimates was not significantly different (p=0.60). However, when modeled with height z-score at age 13 years, the difference was significant (p=0.024) with the HR for age 13 years (1.144, 95%CI:1.098, 1.191) being greater in magnitude than the HR for height z-score change (1.022, 95%CI:0.944, 1.106). The differences between the HRs for height z-score at age 7 years (0.979, 95%CI:0.904, 1.060) and height z-score at age 13 years (1.168, 95%CI:1.079, 1.265) from a mutually adjusted model were also statistically significant (p=0.024).

Discussion

In this analysis of a cohort based in the CSHRR—comprising 125,211 males, over 2.5 million person-years of follow-up, and 2,987 incident prostate cancers—we find evidence for a positive, linear association between childhood height and future prostate cancer risk. This relationship was driven by height at age 13 years as opposed to height change during childhood or height at age 7 years. There were tentative indications that these associations were strongest when restricted to prostate cancers diagnosed in the pre-PSA era. Although the association between birth weight and prostate cancer risk was positive, it was not statistically significant.

There is one previous study of childhood height in relation to prostate cancer risk, and this was from the Boyd Orr cohort which recruited 4,999 children, aged between 2 and 14 years, and resident in England or Scotland during the years 1937–1939 (22). In a single analysis, with adjustment for age at height measurement (baseline), the authors found a point estimate similar to what we present herein between childhood height and risk of prostate cancer (ORper standard deviation of height z-score=1.10; 95%CI: 0.80, 1.51). Although this was not statistically significant, the analysis was underpowered with the accrual of just 33 prostate cancers during the 59-year follow-up of 1,236 boys for whom information on childhood height was available.

In contrast, there have been numerous studies of adult height in relation to prostate cancer. A recent meta-analysis of 58 studies found adult height to be positively associated with prostate cancer (ORper 10 cm=1.06; 95%CI: 1.03, 1.09), which was stronger when restricted to prospective studies of more advanced/aggressive disease (ORper 10 cm=1.12; 95%CI: 1.05, 1.19) (21). In addition, an analysis of individual participant data of more than 1 million individuals from 121 prospective studies indicated that adult height was associated with risk of prostate cancer death (HRper standard deviation of adult height z-score (6.5cm)=1.07; 95%CI: 1.02, 1.11) with evidence of little heterogeneity (I2=9%, 95% uncertainty interval: 0, 36%) (20). Given that our CSHRR estimates of childhood height and prostate cancer risk are similar in magnitude and the fact that these relationships were driven by height at age 13 years, as opposed to height change or height at age 7 years, may indicate that the causal risk mechanism is most dependent on late childhood or even early adolescent growth. Alternatively, distinct effects could be conferred by exposures at two or more growth periods during development.

Although in utero is an important period for normal growth and development, variability in anthropometric measures at birth are thought to represent a distinct set of causal factors compared with those represented by childhood height (40–43). Underlying this proposition is the independence of these anthropometric measures attributable to variability in growth trajectory, which has given rise to the terms such as catch-up and catch-down growth (41–46). However, birth weight is related to childhood height, albeit weakly (r ~ 0.2–0.3) (40, 47, 48), and thus deserves investigation. We found that adjustment for birth weight had no effect on associations between childhood height and prostate cancer risk. Birth weight, itself, provided only tentative evidence for a positive association with prostate cancer risk but this was not statistically significant (HR=1.035; 95%CI: 0.982, 1.091), a finding which is in agreement with a majority of previous studies (23–28) including a previous analysis of CSHRR data (31), although two further studies have provided positive estimates that were just beyond the nominal threshold of statistically significance (p<0.05)(29, 30).

Birth length shares an even weaker correlation with childhood/adolescent height (r~0.11) (49). Birth length was not available in this cohort for analysis, and it has generally not been associated with prostate cancer risk (23, 25, 26, 28). The Norwegian study by Nilsen et al. (26) did find a statistically significant association between birth length and metastatic prostate cancer (RRhighest quartile vs. lowest=2.5; 95%CI: 1.0, 6.3), but this was a sub-analysis that included just 33 cancers with no evidence for linearity of association (p=0.30). In summary, the evidence may suggest that our finding of an association between childhood height and prostate cancer risk is unlikely to be explained by causal factors of in utero growth, as represented by birth length or birth weight. This is compounded by the fact that the CSHRR associations with prostate cancer risk were driven by height at age 13 years.

Therefore, we propose that our observations indicate late childhood, and possibly adolescent, growth phases as important for prostate cancer risk. Previous studies of the relationship between adult height and cancer have attempted to identify the relevant growth period at which the causal factors are experienced via analysis of the components of height. This idea is based on the premise that leg length represents pre-adolescent growth and trunk length represents adolescent growth (50–53). Although previous studies of such find no evidence for stronger associations of one metric compared to the other in relation to prostate cancer risk (21, 22, 54), this does not contradict the evidence and thesis we present here. These studies are using anthropometric measures at least twice-removed from any causal factor (leg length to pre-adolescent growth to causal factor), and leg length and trunk length are obviously not wholly attributable to pre-adolescent and adolescent growth periods, respectively (50, 53, 55). As such, while these metrics are somewhat useful for studies of adult height in attempting to discern the relevant time window (age) for causal factors, they are weaker evidence when compared with measured heights at the relevant ages as used in this analysis of CSHRR data.

The relevant time window(s) (ages) and exposures that underlie the association between height and prostate cancer risk remain elusive. Several ideas for the mechanism have been hypothesized and some of these fit with our proposed time window of exposure, such as insulin-like growth factor pathways (56–59), micronutrients (60–62), calorie intake (63–65), infections (66), psychosocial stresses (36), ill health (36), genetic variants (67) sex steroid hormones (7), and age at onset of puberty (68) Although the weight of the prostate organ makes only relatively small gains between birth and the onset of puberty, going from approximately 1 gram to 4 grams in weight (5, 6), there is continued prostate development including duct formation, solid budding at the periphery and morphogenesis (8). Thus although pubertal development is obviously important for correct adult form and function, the possibility exists that maldevelopment(s) in early (childhood) prostate development may have effects on risk of malignancy later in life. The effect is unlikely to be due to maternal height, given that this has been found not to be associated with subsequent risk of prostate cancer in born sons (69). Also unlikely, for prostate cancer, is the idea that an increased number of cells are at risk in taller individuals (70), given that prostate weight does not appear to be associated with adult height (71).

Overdiagnosis (10, 11) and changes in the composition of prostate cancer populations under study attributable to PSA screening (12–14) were our motivations to conduct pre- and post-PSA era analyses. As described, we found indications of a stronger association between childhood height and prostate cancer risk in the pre-PSA era, which may suggest that PSA-screening has diluted the proportion of clinically-relevant prostate cancer, attenuating the magnitude of observed associations. However, the differences between pre- and post-PSA era estimates were not statistically significant, possibly due to the small number of pre-PSA era prostate cancers in our analysis. Therefore, although this result is provocative, it must be interpreted with caution.

Strengths of this analysis include: prospective and serial measurement of boys’ heights, as opposed to recall or estimation of such in an interview decades after the time-period in question; record linkage via CPR numbers which enabled passive and accurate follow-up; a large, unselected population for study which has provided for a considerable number of prostate cancer outcomes and, in-turn, a high level of confidence in estimates of risk; and, estimation of z-scores and the baseline hazard of the Cox models were both stratified by birth cohort, in an attempt to exclude the possibility of confounding by an unidentified birth cohort effect. Limitations of our analysis include the inability to adjust our estimates for social or lifestyle factors, due to limited availability of such (32). However, the fact that there was no appreciable birth cohort influences on our estimates, despite dramatic changes in social conditions and lifestyle over the many years covered by the cohort, it is unlikely that these factors play a role. Another limitation is our inability to stratify by Gleason score—a histopathologic grading associated with prognosis (72)—as this information is not included in the Danish Cancer Registry. Residual confounding may be considered to be another limitation, but we do not propose that childhood height is itself a risk factor for prostate cancer—rather we propose that height is a proxy for the causal factor.

In conclusion, using CSHRR data we have shown that measured childhood height is positively associated with prostate cancer risk later in life, while there was little evidence for an association with birth weight. The fact that the association was driven by height at age 13 years implicates late childhood, adolescence and adulthood as the potential exposure window of interest. The causal factor may not be singular given the complexity of human growth (19) and carcinogenesis. Adoption of a life-course approach (9) to both the design and analysis of future studies may help elucidate the relationships that underlie these observations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

FUNDING

Intramural Program of the National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health, Department of Health and Human Services.

The research leading to these results has received funding from the European Research Council under the European Union’s Seventh Framework Programme (FP/2007-2013) / ERC Grant Agreement no. 281418, childgrowth2cancer to JLB.

Footnotes

There are no financial disclosures from any of the authors.

References

- 1.Cheng I, Witte JS, McClure LA, Shema SJ, Cockburn MG, John EM, et al. Socioeconomic status and prostate cancer incidence and mortality rates among the diverse population of California. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1431–40. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9369-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hemminki K. Familial risk and familial survival in prostate cancer. World J Urol. 2012;30:143–8. doi: 10.1007/s00345-011-0801-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.McCracken M, Olsen M, Chen MS, Jr, Jemal A, Thun M, Cokkinides V, et al. Cancer incidence, mortality, and associated risk factors among Asian Americans of Chinese, Filipino, Vietnamese, Korean, and Japanese ethnicities. CA Cancer J Clin. 2007;57:190–205. doi: 10.3322/canjclin.57.4.190. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Eeles RA, Olama AAA, Benlloch S, Saunders EJ, Leongamornlert DA, Tymrakiewicz M, et al. Identification of 23 new prostate cancer susceptibility loci using the iCOGS custom genotyping array. Nat Genet. 2013;45:385–91. doi: 10.1038/ng.2560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Swyer GIM. Post-natal growth changes in the human prostate. J Anat. 1944;78:130–45. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wilson JD. The Critical Role of Androgens in Prostate Development. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2011;40:577–90. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2011.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Timms BG. Prostate development: a historical perspective. Differentiation. 2008;76:565–77. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-0436.2008.00278.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Timms BG, Mohs TJ, Didio LJ. Ductal budding and branching patterns in the developing prostate. J Urol. 1994;151:1427–32. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35273-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sutcliffe S, Colditz GA. Prostate cancer: is it time to expand the research focus to early-life exposures? Nat Rev Cancer. 2013;13:208–518. doi: 10.1038/nrc3434. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Welch HG, Albertsen PC. Prostate cancer diagnosis and treatment after the introduction of prostate-specific antigen screening: 1986–2005. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:1325–9. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djp278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Etzioni R, Penson DF, Legler JM, di Tommaso D, Boer R, Gann PH, et al. Overdiagnosis due to prostate-specific antigen screening: lessons from U.S. prostate cancer incidence trends. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2002;94:981–90. doi: 10.1093/jnci/94.13.981. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Stephenson RA. Prostate cancer trends in the era of prostate-specific antigen. An update of incidence, mortality, and clinical factors from the SEER database. Urol Clin North Am. 2002;29:173–81. doi: 10.1016/s0094-0143(02)00002-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Carpenter WR, Howard DL, Taylor YJ, Ross LE, Wobker SE, Godley PA. Racial differences in PSA screening interval and stage at diagnosis. Cancer Causes Control. 2010;21:1071–80. doi: 10.1007/s10552-010-9535-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Jani AB, Vaida F, Hanks G, Asbell S, Sartor O, Moul JW, et al. Changing face and different countenances of prostate cancer: racial and geographic differences in prostate-specific antigen (PSA), stage, and grade trends in the PSA era. Int J Cancer. 2001;96:363–71. doi: 10.1002/ijc.1035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Haas GP, Delongchamps N, Brawley OW, Wang CY, de la Roza G. The worldwide epidemiology of prostate cancer: perspectives from autopsy studies. Can J Urol. 2008;15:3866–71. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Franks LM. Latent carcinoma of the prostate. J Pathol Bacteriol. 1954;68:603–16. doi: 10.1002/path.1700680233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sakr WA, Haas GP, Cassin BF, Pontes JE, Crissman JD. The frequency of carcinoma and intraepithelial neoplasia of the prostate in young male patients. J Urol. 1993;150:379–85. doi: 10.1016/s0022-5347(17)35487-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Zlotta AR, Egawa S, Pushkar D, Govorov A, Kimura T, Kido M, et al. Prevalence of Prostate Cancer on Autopsy: Cross-Sectional Study on Unscreened Caucasian and Asian Men. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2013 doi: 10.1093/jnci/djt151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Whitley E, Gunnell D, Davey Smith G, Holly JM, Martin RM. Childhood circumstances and anthropometry: the Boyd Orr cohort. Ann Hum Biol. 2008;35:518–34. doi: 10.1080/03014460802294250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Emerging Risk Factors C. Adult height and the risk of cause-specific death and vascular morbidity in 1 million people: individual participant meta-analysis. Int J Epidemiol. 2012;41:1419–33. doi: 10.1093/ije/dys086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zuccolo L, Harris R, Gunnell D, Oliver S, Lane JA, Davis M, et al. Height and prostate cancer risk: a large nested case-control study (ProtecT) and meta-analysis. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2008;17:2325–36. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-08-0342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Whitley E, Martin RM, Davey Smith G, Holly JM, Gunnell D. Childhood stature and adult cancer risk: the Boyd Orr cohort. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:243–51. doi: 10.1007/s10552-008-9239-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Boland LL, Mink PJ, Bushhouse SA, Folsom AR. Weight and length at birth and risk of early-onset prostate cancer (United States) Cancer Causes Control. 2003;14:335–8. doi: 10.1023/a:1023930318066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cnattingius S, Lundberg F, Sandin S, Gronberg H, Iliadou A. Birth characteristics and risk of prostate cancer: the contribution of genetic factors. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2009;18:2422–6. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-09-0366. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ekbom A, Wuu J, Adami HO, Lu CM, Lagiou P, Trichopoulos D, et al. Duration of gestation and prostate cancer risk in offspring. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2000;9:221–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Nilsen TI, Romundstad PR, Troisi R, Vatten LJ. Birth size and subsequent risk for prostate cancer: a prospective population-based study in Norway. Int J Cancer. 2005;113:1002–4. doi: 10.1002/ijc.20674. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Platz EA, Giovannucci E, Rimm EB, Curhan GC, Spiegelman D, Colditz GA, et al. Retrospective analysis of birth weight and prostate cancer in the Health Professionals Follow-up Study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:1140–4. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a009412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ekbom A, Hsieh CC, Lipworth L, Wolk A, Ponten J, Adami HO, et al. Perinatal characteristics in relation to incidence of and mortality from prostate cancer. BMJ. 1996;313:337–41. doi: 10.1136/bmj.313.7053.337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eriksson M, Wedel H, Wallander MA, Krakau I, Hugosson J, Carlsson S, et al. The impact of birth weight on prostate cancer incidence and mortality in a population-based study of men born in 1913 and followed up from 50 to 85 years of age. Prostate. 2007;67:1247–54. doi: 10.1002/pros.20428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ferguson P, Mohr L, Hoel D, Lipsitz S, Lackland D. Possible relationship between birth weight and cancer incidence among young adults. Ann Epidemiol. 2000;10:471. doi: 10.1016/s1047-2797(00)00104-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ahlgren M, Wohlfahrt J, Olsen LW, Sørensen TIA, Melbye M. Birth weight and risk of cancer. Cancer. 2007;110:412–9. doi: 10.1002/cncr.22773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Baker JL, Olsen LW, Andersen I, Pearson S, Hansen B, Sørensen TIA. Cohort profile: the Copenhagen School Health Records Register. Int J Epidemiol. 2009;38:656–62. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyn164. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Pedersen CB. The Danish Civil Registration System. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:22–5. doi: 10.1177/1403494810387965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gjerstorff ML. The Danish Cancer Registry. Scand J Public Health. 2011;39:42–5. doi: 10.1177/1403494810393562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.World Health Organization. International statistical classification of diseases and related health problems. 2010. Geneva: World Health Organization; 2011. 10th revision. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Batty GD, Shipley MJ, Gunnell D, Huxley R, Kivimaki M, Woodward M, et al. Height, wealth, and health: an overview with new data from three longitudinal studies. Econ Hum Biol. 2009;7:137–52. doi: 10.1016/j.ehb.2009.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cole TJ. The LMS method for constructing normalized growth standards. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1990;44:45–60. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Rugholm S, Baker JL, Olsen LW, Schack-Nielsen L, Bua J, Sørensen TIA. Stability of the association between birth weight and childhood overweight during the development of the obesity epidemic. Obes Res. 2005;13:2187–94. doi: 10.1038/oby.2005.271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mukai TO, Bro F, Pedersen KV, Vedsted P. Use of prostate-specific antigen testing. Ugeskr Laeger. 2010;172:696–700. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Gunnell D, Davey Smith G, McConnachie A, Greenwood R, Upton M, Frankel S. Separating in-utero and postnatal influences on later disease. Lancet. 1999;354:1526–7. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(99)02937-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bogin B, Baker J. Low birth weight does not predict the ontogeny of relative leg length of infants and children: an allometric analysis of the NHANES III sample. Am J Phys Anthropol. 2012;148:487–94. doi: 10.1002/ajpa.22064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Gigante DP, Nazmi A, Lima RC, Barros FC, Victora CG. Epidemiology of early and late growth in height, leg and trunk length: findings from a birth cohort of Brazilian males. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2009;63:375–81. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1602949. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eide MG, Oyen N, Skjoerven R, Nilsen ST, Bjerkedal T, Tell GS. Size at birth and gestational age as predictors of adult height and weight. Epidemiology. 2005;16:175–81. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000152524.89074.bf. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wadsworth ME, Hardy RJ, Paul AA, Marshall SF, Cole TJ. Leg and trunk length at 43 years in relation to childhood health, diet and family circumstances; evidence from the 1946 national birth cohort. Int J Epidemiol. 2002;31:383–90. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Gunnell D, May M, Ben-Shlomo Y, Yarnell J, Davey Smith G. Height, leg length, and cancer: the Caerphilly Study. Nutr Cancer. 2003;47:34–9. doi: 10.1207/s15327914nc4701_4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Okasha M, Gunnell D, Holly J, Davey Smith G. Childhood growth and adult cancer. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2002;16:225–41. doi: 10.1053/beem.2002.0204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Miller FJ, Billewicz WZ, Thomson AM. Growth from birth to adult life of 442 Newcastle upon Tyne children. Br J Prev Soc Med. 1972;26:224–30. doi: 10.1136/jech.26.4.224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Olivier G, Bressac F, Tissier H. Correlations between birth length and adult stature. Hum Biol. 1978;50:69–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Loesch DZ, Huggins RM, Stokes KM. Relationship of birth weight and length with growth in height and body diameters from 5 years of age to maturity. Am J Hum Biol. 1999;11:772–8. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1520-6300(199911/12)11:6<772::AID-AJHB7>3.0.CO;2-H. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Gerver WJ, De Bruin R. Relationship between height, sitting height and subischial leg length in Dutch children: presentation of normal values. Acta Paediatr. 1995;84:532–5. doi: 10.1111/j.1651-2227.1995.tb13688.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Leitch I. Growth and health. Br J Nutr. 1951;5:142–51. doi: 10.1079/bjn19510017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Buckler JMH. Growth at Adolescence. In: Kelnar CJH, Savage MO, Saenger P, Cowell CT, editors. Growth Disorders. 2. Florida, USA: CRC Press; 2007. pp. 150–64. [Google Scholar]

- 53.Scammon RE. The measurement of the body in childhood. In: Harris JA, Jackson CM, Paterson DG, Scammon RE, editors. The Measurement of Man. Minneapolis, MN, USA: University of Minnesota Press; 1930. pp. 173–215. [Google Scholar]

- 54.Chyou PH, Nomura AM, Stemmermann GN. A prospective study of weight, body mass index and other anthropometric measurements in relation to site-specific cancers. Int J Cancer. 1994;57:313–7. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910570304. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Karlberg J, Jalil F, Lam B, Low L, Yeung CY. Linear growth retardation in relation to the three phases of growth. Eur J Clin Nutr. 1994;48 (Suppl 1):S25–43. discussion S–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Neuhouser ML, Platz EA, Till C, Tangen CM, Goodman PJ, Kristal A, et al. Insulin-like growth factors and insulin-like growth factor-binding proteins and prostate cancer risk: results from the prostate cancer prevention trial. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2013;6:91–9. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-12-0250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Price AJ, Allen NE, Appleby PN, Crowe FL, Travis RC, Tipper SJ, et al. Insulin-like growth factor-I concentration and risk of prostate cancer: results from the European Prospective Investigation into Cancer and Nutrition. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2012;21:1531–41. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-12-0481-T. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Tsilidis KK, Travis RC, Appleby PN, Allen NE, Lindstrom S, Albanes D, et al. Insulin-like growth factor pathway genes and blood concentrations, dietary protein and risk of prostate cancer in the NCI Breast and Prostate Cancer Cohort Consortium (BPC3) Int J Cancer. 2013;133:495–504. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28042. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Juul A, Dalgaard P, Blum WF, Bang P, Hall K, Michaelsen KF, et al. Serum levels of insulin-like growth factor (IGF)-binding protein-3 (IGFBP-3) in healthy infants, children, and adolescents: the relation to IGF-I, IGF-II, IGFBP-1, IGFBP-2, age, sex, body mass index, and pubertal maturation. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1995;80:2534–42. doi: 10.1210/jcem.80.8.7543116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Brandstedt J, Almquist M, Manjer J, Malm J. Vitamin D, PTH, and calcium and the risk of prostate cancer: a prospective nested case-control study. Cancer Causes Control. 2012;23:1377–85. doi: 10.1007/s10552-012-9948-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Park SY, Wilkens LR, Morris JS, Henderson BE, Kolonel LN. Serum zinc and prostate cancer risk in a nested case-control study: The multiethnic cohort. Prostate. 2013;73:261–6. doi: 10.1002/pros.22565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Roswall N, Larsen SB, Friis S, Outzen M, Olsen A, Christensen J, et al. Micronutrient intake and risk of prostate cancer in a cohort of middle-aged, Danish men. Cancer Causes Control. 2013;24:1129–35. doi: 10.1007/s10552-013-0190-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Albanes D. Energy balance, body size, and cancer. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 1990;10:283–303. doi: 10.1016/1040-8428(90)90036-r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Fuemmeler BF, Pendzich MK, Tercyak KP. Weight, Dietary Behavior, and Physical Activity in Childhood and Adolescence: Implications for Adult Cancer Risk. Obesity Facts. 2009;2:179–86. doi: 10.1159/000220605. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Dirx MJ, van den Brandt PA, Goldbohm RA, Lumey LH. Energy restriction in childhood and adolescence and risk of prostate cancer: results from the Netherlands Cohort Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:530–7. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.6.530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Ulijaszek SJ. The international growth standard for children and adolescents project: environmental influences on preadolescent and adolescent growth in weight and height. Food Nutr Bull. 2006;27:S279–94. doi: 10.1177/15648265060274S510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Paternoster L, Howe LD, Tilling K, Weedon MN, Freathy RM, Frayling TM, et al. Adult height variants affect birth length and growth rate in children. Hum Mol Genet. 2011;20:4069–75. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddr309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Diamandis EP, Yu H. Does prostate cancer start at puberty? J Clin Lab Anal. 1996;10:468–9. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1098-2825(1996)10:6<468::AID-JCLA27>3.0.CO;2-U. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Barker DJ, Osmond C, Thornburg KL, Kajantie E, Eriksson JG. A possible link between the pubertal growth of girls and prostate cancer in their sons. Am J Hum Biol. 2012;24:406–10. doi: 10.1002/ajhb.22222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Albanes D, Winick M. Are cell number and cell proliferation risk factors for cancer? J Natl Cancer Inst. 1988;80:772–4. doi: 10.1093/jnci/80.10.772. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Sheikhazadi A, Sadr SS, Ghadyani MH, Taheri SK, Manouchehri AA, Nazparvar B, et al. Study of the normal internal organ weights in Tehran’s population. J Forensic Leg Med. 2010;17:78–83. doi: 10.1016/j.jflm.2009.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gleason DF. Classification of prostatic carcinomas. Cancer Chemother Rep. 1966;50:125–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.