Abstract

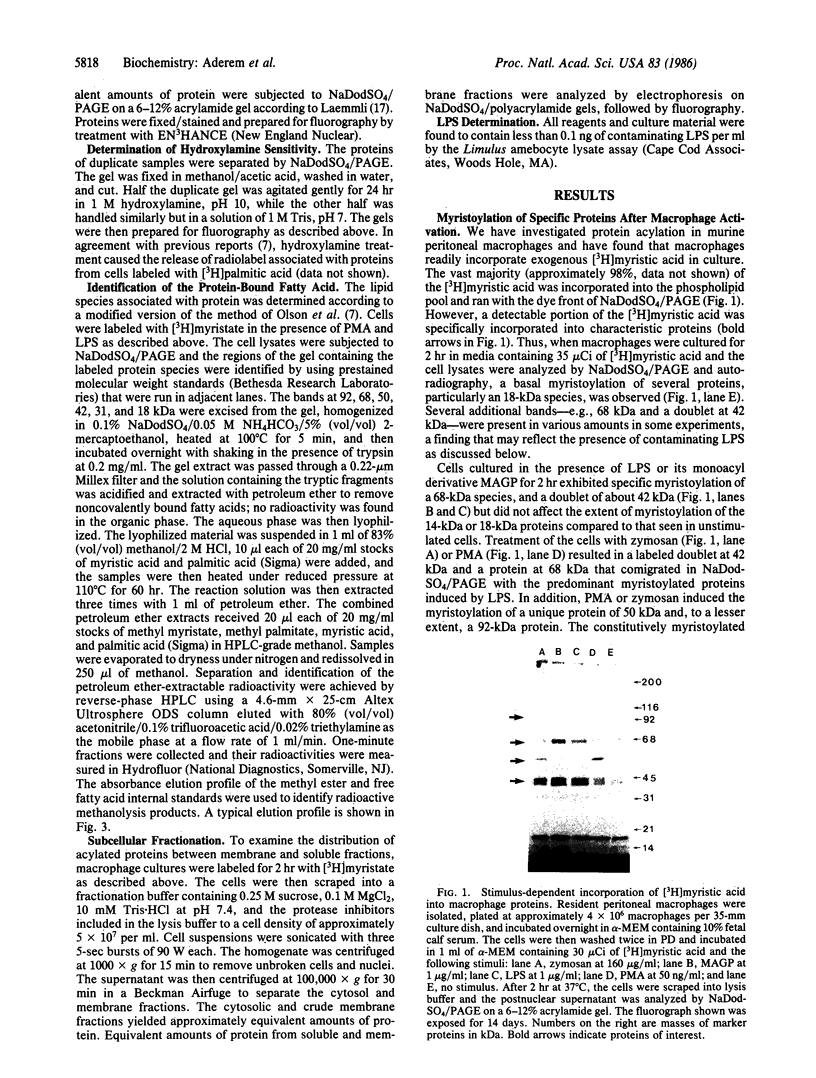

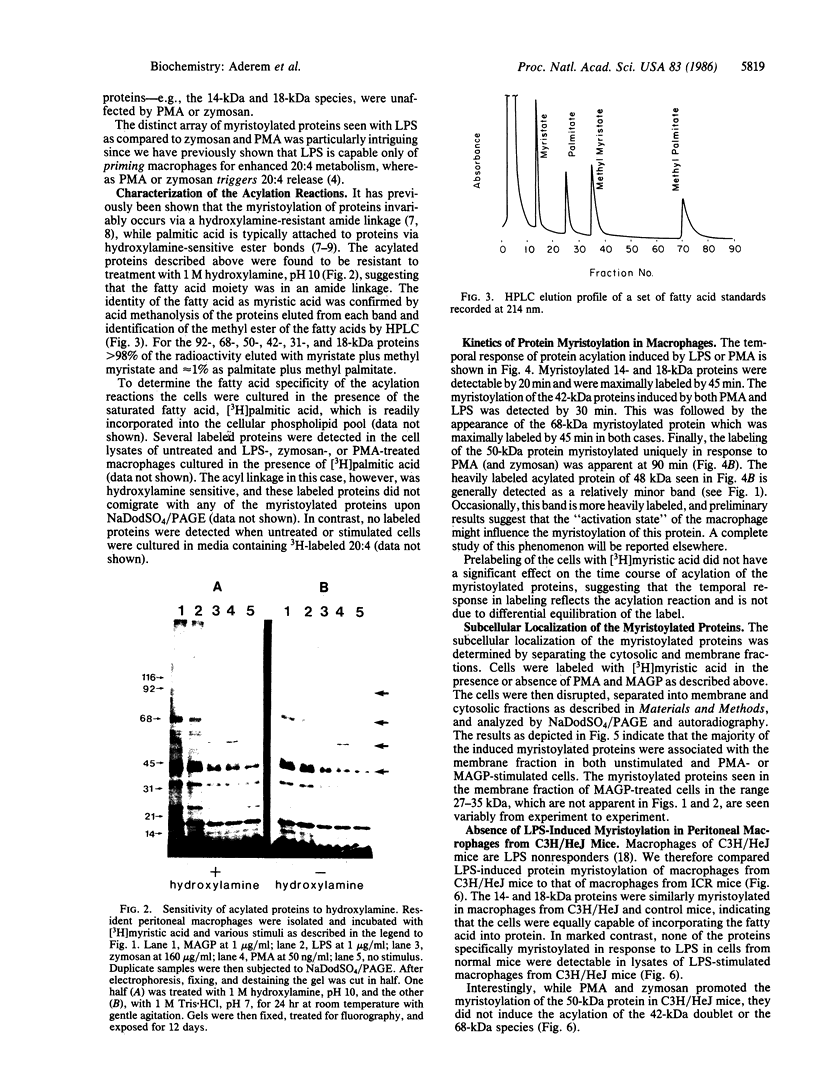

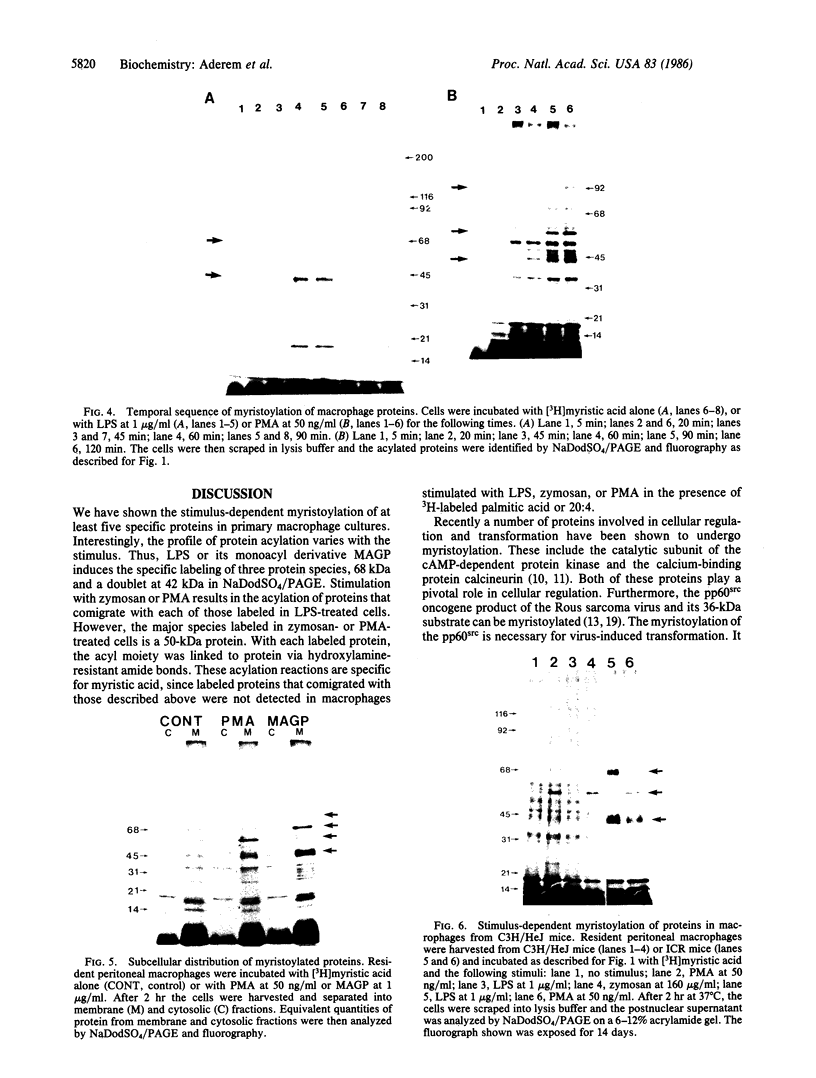

We demonstrate stimulus-dependent incorporation of exogenously added [3H]myristic acid into specific macrophage proteins. In control unstimulated cells an 18-kDa protein is the major acylated species. In cells incubated with bacterial lipopolysaccharide (LPS), or its monoacyl glucosamine phosphate derivative, fatty acid is incorporated into proteins with molecular mass of 68 kDa and a doublet of approximately 42-45 kDa. Phorbol 12-myristate 13-acetate (PMA) or a phagocytic stimulus (zymosan) promotes the acylation of a similar array of proteins. However, PMA and zymosan also promote the myristoylation of unique proteins of 92 and 50 kDa. The fatty acid associated with each of the acylated proteins is myristic acid. The myristate is probably linked to the proteins through amide bonds, since it is not released by treatment with hydroxylamine. Palmitate and arachidonate are not incorporated into proteins in the same manner. Temporal analysis revealed that LPS-induced proteins are myristoylated by 30 min, while the 50-kDa protein myristoylated in response to PMA is labeled later. Most myristoylated proteins appear to be associated with the membrane fraction. Macrophages from C3H/HeJ mice, which do not respond to LPS, do not show any LPS-dependent protein acylation. Interestingly, zymosan and PMA induce the myristoylation of the 50-kDa protein in C3H/HeJ macrophages, but not the acylation of the 68-kDa and 42-kDa doublet species. We suggest that myristoylation of specific proteins is an intermediary in the capacity of LPS, PMA, and zymosan to alter macrophage functions such as arachidonic acid metabolism.

Full text

PDF

Images in this article

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Aderem A. A., Cohen D. S., Wright S. D., Cohn Z. A. Bacterial lipopolysaccharides prime macrophages for enhanced release of arachidonic acid metabolites. J Exp Med. 1986 Jul 1;164(1):165–179. doi: 10.1084/jem.164.1.165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken A., Cohen P., Santikarn S., Williams D. H., Calder A. G., Smith A., Klee C. B. Identification of the NH2-terminal blocking group of calcineurin B as myristic acid. FEBS Lett. 1982 Dec 27;150(2):314–318. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(82)80759-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bonney R. J., Wightman P. D., Davies P., Sadowski S. J., Kuehl F. A., Jr, Humes J. L. Regulation of prostaglandin synthesis and of the selective release of lysosomal hydrolases by mouse peritoneal macrophages. Biochem J. 1978 Nov 15;176(2):433–442. doi: 10.1042/bj1760433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- COHN Z. A., BENSON B. THE DIFFERENTIATION OF MONONUCLEAR PHAGOCYTES. MORPHOLOGY, CYTOCHEMISTRY, AND BIOCHEMISTRY. J Exp Med. 1965 Jan 1;121:153–170. doi: 10.1084/jem.121.1.153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr S. A., Biemann K., Shoji S., Parmelee D. C., Titani K. n-Tetradecanoyl is the NH2-terminal blocking group of the catalytic subunit of cyclic AMP-dependent protein kinase from bovine cardiac muscle. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1982 Oct;79(20):6128–6131. doi: 10.1073/pnas.79.20.6128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies P., Bailey P. J., Goldenberg M. M., Ford-Hutchinson A. W. The role of arachidonic acid oxygenation products in pain and inflammation. Annu Rev Immunol. 1984;2:335–357. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.02.040184.002003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraft A. S., Anderson W. B. Phorbol esters increase the amount of Ca2+, phospholipid-dependent protein kinase associated with plasma membrane. Nature. 1983 Feb 17;301(5901):621–623. doi: 10.1038/301621a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LOWRY O. H., ROSEBROUGH N. J., FARR A. L., RANDALL R. J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J Biol Chem. 1951 Nov;193(1):265–275. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Laemmli U. K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature. 1970 Aug 15;227(5259):680–685. doi: 10.1038/227680a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magee A. I., Courtneidge S. A. Two classes of fatty acid acylated proteins exist in eukaryotic cells. EMBO J. 1985 May;4(5):1137–1144. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1985.tb03751.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchildon G. A., Casnellie J. E., Walsh K. A., Krebs E. G. Covalently bound myristate in a lymphoma tyrosine protein kinase. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1984 Dec;81(24):7679–7682. doi: 10.1073/pnas.81.24.7679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishijima M., Amano F., Akamatsu Y., Akagawa K., Tokunaga T., Raetz C. R. Macrophage activation by monosaccharide precursors of Escherichia coli lipid A. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Jan;82(2):282–286. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.2.282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishizuka Y. The role of protein kinase C in cell surface signal transduction and tumour promotion. Nature. 1984 Apr 19;308(5961):693–698. doi: 10.1038/308693a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olson E. N., Towler D. A., Glaser L. Specificity of fatty acid acylation of cellular proteins. J Biol Chem. 1985 Mar 25;260(6):3784–3790. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellman D., Garber E. A., Cross F. R., Hanafusa H. An N-terminal peptide from p60src can direct myristylation and plasma membrane localization when fused to heterologous proteins. 1985 Mar 28-Apr 3Nature. 314(6009):374–377. doi: 10.1038/314374a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pellman D., Garber E. A., Cross F. R., Hanafusa H. Fine structural mapping of a critical NH2-terminal region of p60src. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1985 Mar;82(6):1623–1627. doi: 10.1073/pnas.82.6.1623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Raetz C. R., Purcell S., Takayama K. Molecular requirements for B-lymphocyte activation by Escherichia coli lipopolysaccharide. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1983 Aug;80(15):4624–4628. doi: 10.1073/pnas.80.15.4624. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schlesinger M. J. Proteolipids. Annu Rev Biochem. 1981;50:193–206. doi: 10.1146/annurev.bi.50.070181.001205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Scott W. A., Zrike J. M., Hamill A. L., Kempe J., Cohn Z. A. Regulation of arachidonic acid metabolites in macrophages. J Exp Med. 1980 Aug 1;152(2):324–335. doi: 10.1084/jem.152.2.324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soric J., Gordon J. A. The 36-kilodalton substrate of pp60v-src is myristylated in a transformation-sensitive manner. Science. 1985 Nov 1;230(4725):563–566. doi: 10.1126/science.2996139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sultzer B. M. Genetic control of leucocyte responses to endotoxin. Nature. 1968 Sep 21;219(5160):1253–1254. doi: 10.1038/2191253a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]