Abstract

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small non-protein-coding RNAs that bind to specific mRNAs and inhibit translation or promote mRNA degradation. Recent reports have indicated that miR-33, which is located within the intron of sterol regulatory element-binding protein (SREBP) 2, controls cholesterol homoeostasis and may be a potential therapeutic target for the treatment of atherosclerosis. Here we show that deletion of miR-33 results in marked worsening of high-fat diet-induced obesity and liver steatosis. Using miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice, we demonstrate that SREBP-1 is a target of miR-33 and that the mechanisms leading to obesity and liver steatosis in miR-33−/− mice involve enhanced expression of SREBP-1. These results elucidate a novel interaction between SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 mediated by miR-33 in vivo.

The micro-RNA miR-33 is encoded by an intron of the gene encoding sterol regulatory-binding protein 2 (SREBP-2) and controls cholesterol homoeostasis. Here, Horie et al. identify SREBP-1 as a target of miR-33 and show that deletion of miR-33 promotes diet-induced obesity and liver steatosis in mice.

The micro-RNA miR-33 is encoded by an intron of the gene encoding sterol regulatory-binding protein 2 (SREBP-2) and controls cholesterol homoeostasis. Here, Horie et al. identify SREBP-1 as a target of miR-33 and show that deletion of miR-33 promotes diet-induced obesity and liver steatosis in mice.

Sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs) are the predominant transcription factors controlling the synthesis of cholesterol and fatty acids in the liver1. The family of SREBPs essentially encompasses two isoforms, SREBP-1 and SREBP-2, encoded by the corresponding genes SREBF1 and SREBF2 (refs 2, 3). In contrast to SREBP-2, SREBP-1 is transcribed into two major splicing variants, SREBP-1a and SREBP-1c, which differ only in their first exon through the use of alternative promoters2,3. Although there is some functional overlap among the three SREBP isoforms4, these proteins regulate different metabolic pathways. SREBP-2 is the master regulator of cholesterol synthesis and metabolism, whereas SREBP-1c controls fatty acid synthesis in the liver and adipose tissue5. In replicating tumour cell lines, SREBP-1a mostly transactivates both lipogenic and cholesterogenic genes. Although SREBP-1a and SREBP-1c share the same bHLH and regulatory domains, SREBP-1a is a stronger activator than SREBP-1c owing to a longer amino-terminal transactivation domain6. Therefore, SREBP-1a, -1c and -2 have specific roles in the regulation of cholesterol and fatty acids. In order to fine-tune cellular metabolism efficiently, it may be important to regulate their functions in an interdependent manner. However, limited evidence has been obtained about the potential interactions between SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 until date.

MicroRNAs (miRs) are small non-protein-coding RNAs that bind to specific mRNAs and inhibit translation or promote mRNA degradation. miR-33 is encoded in an intron of SREBF2. The sequence of miR-33 is identical, and the stem-loop of the pre-miRNA is highly conserved in mammals7,8,9,10. Recent reports, including ours, have indicated that miR-33 controls ABCA1 expression and reduces HDL-C levels, and that miR-33 is a potential target for the treatment of atherosclerosis11,12. To determine the organ/cell type-specific function of miRs in the long term in vivo, studies on miRNA-deficient mice and analysis of specific organ/cell types from these mice are needed. Therefore, we generated miR-33-deficient mice and studied their phenotypes. We noted that miR-33-deficient mice gradually gained more weight than control mice, and the obese phenotype was evident after 26 weeks of age when receiving normal chow (NC). When we fed them a high-fat diet (HFD), miR-33-deficient mice became severely obese and suffered from liver steatosis. Microarray analysis showed that genes involved in fatty acid metabolism were upregulated in miR-33−/− mice fed NC before becoming obese. We searched for potential target genes of miR-33 in a public database (TargetScan, http://www.targetscan.org), and found that one of the targets of miR-33 is SREBP-1. In vitro experiments indicated that SREBP-1 is a likely target of miR-33. We further intercrossed miR-33−/− mice with Srebf1+/− mice and fed them HFD. The difference in body weight (BW) between miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice and miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice decreased and hepatic steatosis was reversed in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice compared with miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice under pair-feeding conditions. These data demonstrate that miR-33 targets SREBP-1 in vivo.

In the present study, we demonstrated that miR-33 deficiency increases SREBP-1 levels, fatty acid synthesis, and fatty acid accumulation in the liver and adipose tissue. These results indicate a novel relationship between SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 through miR-33.

Results

miR-33-KO mice become obese and develop hepatic steatosis

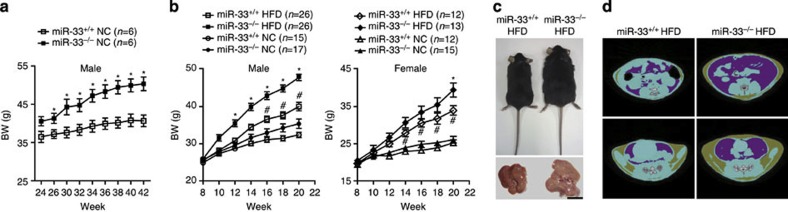

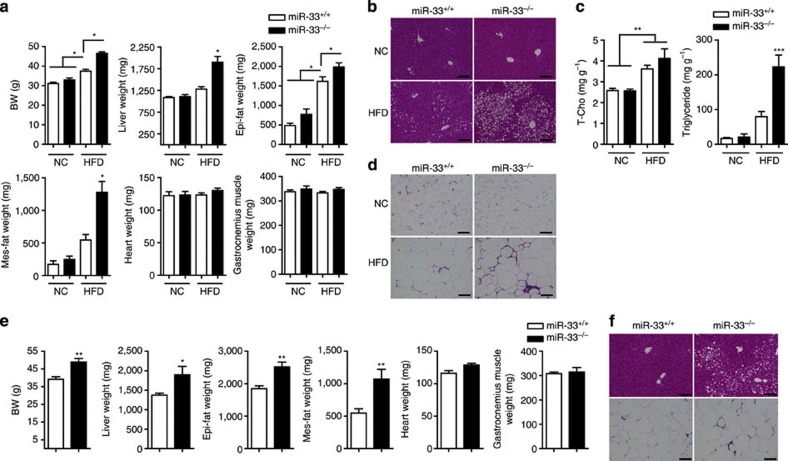

Twenty-six-week-old male miR-33-knockout mice weighed more than wild-type (WT) littermates after being fed NC (Fig. 1a). Up to 24 weeks of age, the BWs of the miR-33−/− mice and those of age- and sex-matched miR-33+/+ control mice did not differ, but 26-week-old male miR-33−/− mice were 20% heavier than controls. After feeding with HFD from 8 to 20 weeks of age, miR-33−/− mice become markedly obese compared with controls of both genders (Fig. 1b,c). Computed tomography (CT) of 20-week-old miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed HFD showed a severe increase in body fat of miR-33−/− mice compared with miR-33+/+ mice (Fig. 1d). We estimated fat weight from CT values because there is a good correlation of visceral fat weight and calculated weight from CT values (Supplementary Fig. S1a). Both visceral and subcutaneous fat weights were higher in miR-33−/− mice fed HFD (Supplementary Fig. S1b). Figure 2a indicates that the increased BW was caused by an increase in liver and adipose tissue weight. The livers of miR-33−/− mice fed HFD were severely enlarged and pale in colour (Fig. 1c). Histological examination revealed that miR-33−/− mice fed HFD developed severe fatty liver with the accumulation of lipid droplets (Fig. 2b). We measured total cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the liver and found that triglyceride levels were significantly increased in the liver of miR-33−/− mice fed HFD compared with miR-33+/+ mice fed HFD and mice fed NC (Fig. 2c right). On the other hand, cholesterol levels in the liver were increased in mice fed HFD compared with mice fed NC and there was no difference between miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice (Fig. 2c left). Figure 2d shows the increase in adipocyte size with the accumulation of infiltrated cells in white adipose tissue in miR-33−/− mice fed HFD. It is of note that the same phenotypes as those of miR-33−/− mice fed HFD were also observed in miR-33−/− mice fed NC at 50 weeks of age (Fig. 2e,f). Thus, genetic ablation of miR-33 induces obesity and hepatic steatosis.

Figure 1. miR-33−/− mice become obese and develop hepatic steatosis.

(a) Development of BW of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− male mice fed NC. *P<0.05 versus NC-fed miR-33+/+ mice. Statistical comparisons were made by Student’s t-test. (b) Development of BW of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed or not fed HFD. *P<0.05 versus HFD-fed miR-33+/+ mice, #P<0.05 versus NC-fed miR-33+/+ mice. Statistical comparisons were made by one-way analysis of valiance test. (c) Representative image of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed with a HFD. Lower images show the livers of these mice. Scale bars, 1.0 cm. (d) Representative CT images of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed HFD. Values are the means±s.e.m.

Figure 2. Pathophysiological features of miR-33−/− mice.

(a) Body, liver, adipose tissue (epi-fat; epididymal fat, mes-fat; mesenteric fat), heart and muscle weights of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed or not fed HFD (n=12–13 for NC, n=21 for HFD each. *P<0.05 in one-way analysis of valiance test). (b) Representative microscopic images of the livers of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed or not fed HFD. Scale bars, 200 μm. (c) Cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the livers of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed or not fed HFD (n=5 each. **P<0.01, ***P<0.001 in one-way analysis of valiance test). (d) Representative microscopic images of the adipose tissue (epididymal fat) of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed or not fed HFD. Scale bars, 200 μm. (e) Body, liver, adipose tissue, heart and muscle weights of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at the age of 50 weeks (n=6 each, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 in Student’s t-test). (f) Representative microscopic images of the liver and the adipose tissue of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at the age of 50 weeks. Scale bars, 200 μm. Values are the means±s.e.m.

miR-33-KO mice have abnormal glucose and insulin tolerance

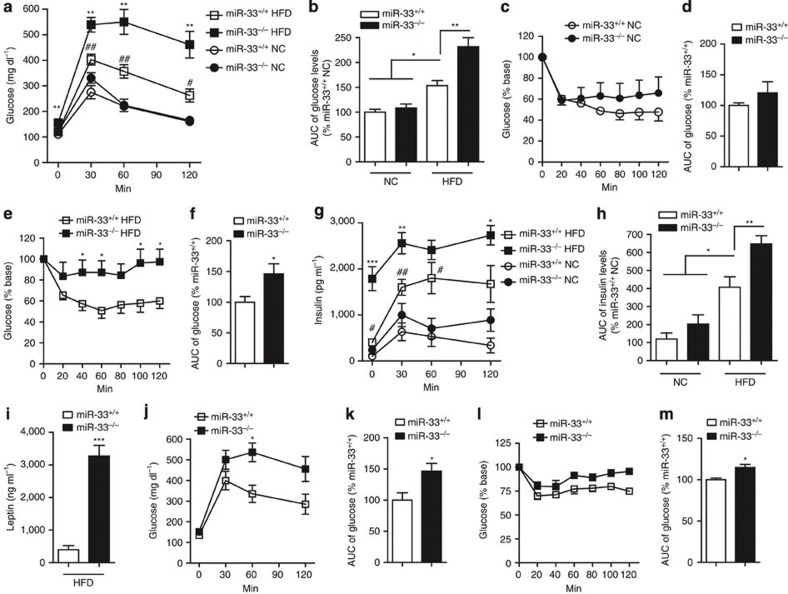

miR-33−/− mice fed HFD from 8 weeks to 20 weeks of age showed higher fasting glucose levels and severely impaired glucose tolerance at 20 weeks (Fig. 3a,b).

Figure 3. Analysis of glucose and insulin tolerance.

(a,b) Serial changes in glucose levels (a) and area under curve (AUC) of glucose levels (b) after intraperitoneal injection of glucose in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed or not fed HFD (n=6 for NC, n=11–12 for HFD each. *P<0.05 versus mice fed NC. **P<0.01 versus miR-33+/+ mice fed HFD. #P<0.05 versus miR-33+/+ mice fed NC, ##P<0.01 versus miR-33+/+ mice fed NC in one-way analysis of valiance test). (c,d) Serial changes in glucose levels (c) and AUC of glucose levels (d) after intraperitoneal injection of insulin in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC (n=5 each). (e,f) Serial changes in glucose levels (e) and AUC of glucose levels (f) after intraperitoneal injection of insulin in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed HFD (n=9 each, *P<0.05 in Student’s t-test). (g) Serial changes in insulin levels after intraperitoneal injection of glucose in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed or not fed HFD (n=6 for NC, n=11–12 for HFD each. *P<0.05 versus miR-33+/+ mice fed HFD, **P<0.01 versus miR-33+/+ mice fed HFD, ***P<0.001 versus miR-33+/+ mice fed HFD, #P<0.05 versus miR-33+/+ mice fed NC, ##P<0.01 versus miR-33+/+ mice fed NC in one-way analysis of valiance test). (h) AUC of insulin levels after intraperitoneal injection of glucose in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed or not fed HFD (n=6 for NC, n=11–12 for HFD each, *P<0.05, **P<0.01 in one-way analysis of valiance test). (i) Serum leptin levels in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed HFD (n=10 for each, ***P<0.001 in Student’s t-test). (j,k) Serial changes in glucose levels (j) and AUC of glucose levels (k) after intraperitoneal injection of glucose in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at the age of 50 weeks (n=6 each, *P<0.05 in Student’s t-test). (l,m) Serial changes in glucose levels (l) and AUC of glucose levels (m) after intraperitoneal injection of insulin in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at the age of 50 weeks (n=6 each, *P<0.05 in Student’s t-test). Values are the means±s.e.m.

However, miR-33−/− mice fed NC showed the same glucose levels as miR-33+/+ mice at this age. Baseline glucose levels of NC-fed miR-33+/+ mice, NC-fed miR-33−/− mice, HFD-fed miR-33+/+ mice and HFD-fed miR-33−/− mice were 110.5±8.3, 122±2.5, 120.5±5.6 and 155.6±6.7 mg dl−1, respectively (All values represent mean±s.e.m.). Impaired insulin tolerance was observed only in miR-33−/− mice fed HFD (Fig. 3c–f). Insulin levels in intraperitoneal glucose tolerance test (IPGTT) were significantly elevated in miR-33−/− mice fed HFD (Fig. 3g,h). Plasma leptin levels were also elevated in miR-33−/− mice fed HFD (Fig. 3i). Impaired glucose tolerance and insulin tolerance were also evident at the age of 50 weeks even in mice fed NC (Fig. 3j–m).

Serum levels of ALP, T-cho and HDL-C were elevated in miR-33−/− mice compared with that in WT mice at the age of 20 weeks, as indicated in our previous report (Table 1)10. When these mice were fed HFD from 8 to 20 weeks of age, increases in serum levels of AST, ALT, NEFA and LDL-C became evident (Table 1). Similar elevation of T-cho was observed in miR-33−/− mice fed NC at the age of 50 weeks compared with controls (Supplementary Table S2).

Table 1. Serum profile of miR-33+/+ and miR-33 −/− on NC or HFD.

| miR-33+/+ NC (n=8) | miR-33−/− NC (n=8) | miR-33+/+ HFD (n=5) | miR-33−/− HFD (n=5) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| AST (IU l−1) | 67.63±5.43 | 56.50±11.89 | 53.80±2.89 | 134.40±18.48** |

| ALT (IU l−1) | 39.38±6.02 | 41.00±11.95 | 31.40±3.92 | 167.40±29.15** |

| ALP (IU l−1) | 186.88±15.29 | 238.13±14.57* | 138.80±9.83 | 210.60±20.79* |

| T-CHO (mg dl−1) | 85.75±3.83 | 110.25±6.16** | 157.40±13.25 | 244.8±21.42** |

| TG (mg dl−1) | 35.63±4.39 | 34.50±4.82 | 21.80±2.33 | 17.60±3.72 |

| NEFA (μEq l−1) | 766.8±30.89 | 867.1±53.68 | 778±61.21 | 979±55.40* |

| LDL-C (mg dl−1) | 5.50±0.63 | 6.88±0.72 | 11.40±0.51 | 26.00±5.30* |

| HDL-C (mg dl−1) | 52.38±2.08 | 66.13±2.72** | 79.00±4.71 | 83.60±1.25 |

Values are the means±s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were made by Student’s t-test (*P<0.05, **P<0.01).

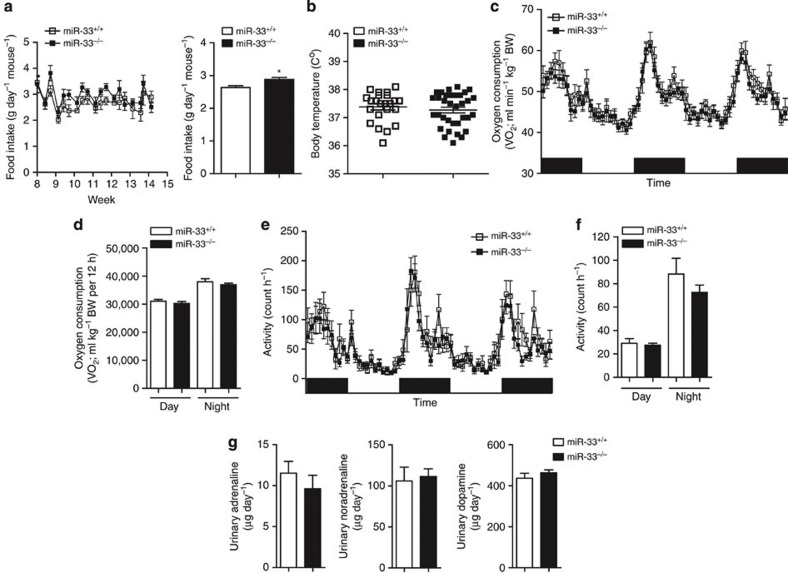

miR-33-KO mice find HFD more palatable

Food intake, as analysed by housing in metabolic cages, was higher in miR-33−/− mice fed HFD than that in their control counterparts (Fig. 4a). The difference in food intake was only observed when they were fed with HFD (Supplementary Fig. S2a, b), which suggests that miR-33−/− mice find HFD more palatable. These mice showed similar body temperatures (37.38 °C versus 37.27 °C) and O2 consumption rate or activity did not differ between these strains during the day or night at the age of 16 weeks when fed NC (Fig. 4c–f). Moreover, urinary excretion of adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine were also the same between these strains at the same age (Fig. 4g).

Figure 4. Analysis of energy balance.

(a) Serial changes in food intake of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed HFD in metabolic cages (n=5–6 each, *P<0.05 in Student’s t-test). (b) Body temperature of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice at 16 weeks of age (n=23, 34 each). (c) Oxygen consumption rate of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at 16 weeks of age (n=8 each). (d) Oxygen consumption during 12 h by miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at 16 weeks of age (n=8 each). (e) Serial changes in activity of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at 16 weeks of age (n=8 each). (f) Day and night activity of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at 16 weeks of age (n=8 each). (g) Urinary secretion of adrenaline, noradrenaline and dopamine (n=3–4 each). Values are the means±s.e.m.

miR-33 regulates SREBP-1 expression in vivo

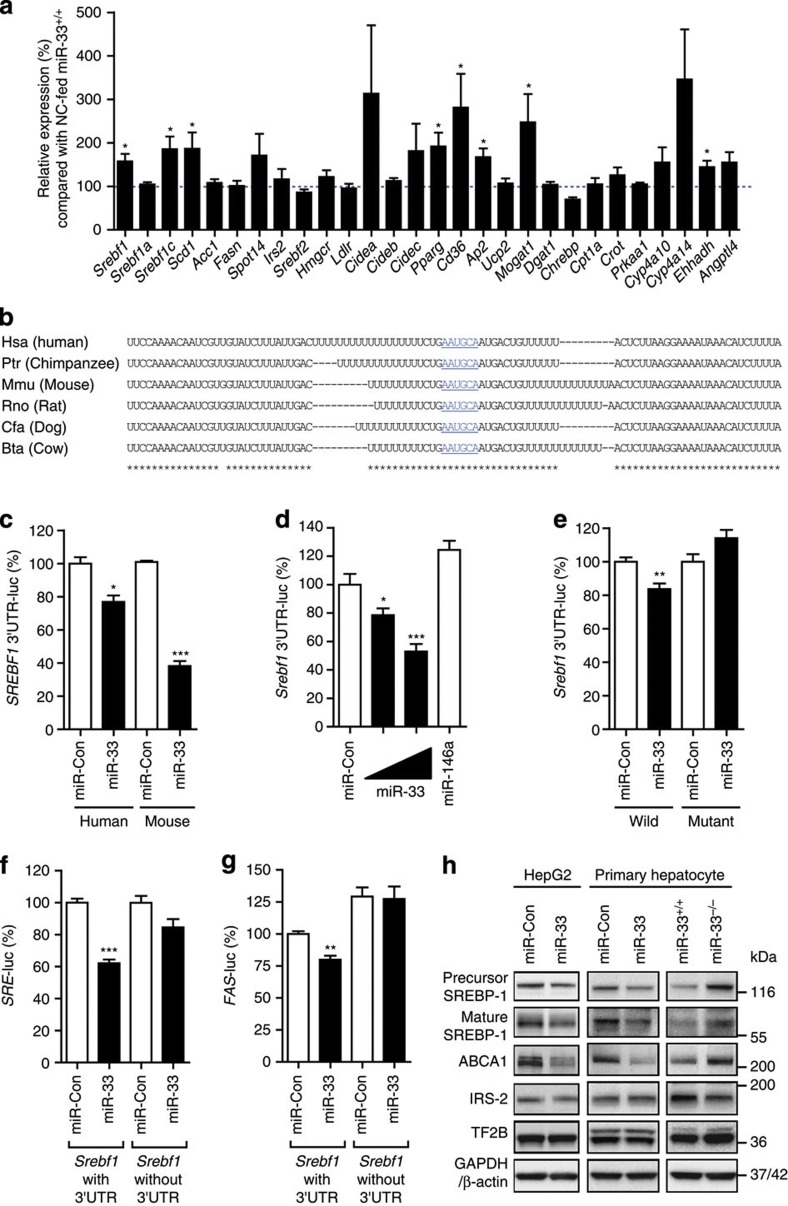

In order to determine the cause of the phenotypic changes observed in miR-33−/−mice fed HFD or in older miR-33−/− mice, we analysed the gene expression profiles by microarray analysis using the livers of miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice fed NC at the age of 16 weeks when their weights were the same. The pathways altered in the livers of miR-33−/− mice were determined by GenMAPP analysis ( http://www.genmapp.org/about.html). Most strikingly, the fatty acid metabolism pathway showed the highest Z score (Supplementary Table S3). We picked up genes related to fatty acid metabolism and validated their expression levels in the liver by quantitative RT–PCR (PCR with reverse transcription). Interestingly, significant differences were observed in the expression levels of several lipogenic genes including Srebf1, Pparg and its downstream genes (Fig. 5a). We also measured de novo hepatic fatty acid synthesis rate, as previously described13,14. It was increased significantly in the miR-33−/− mice compared with that of the miR-33+/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. S3a). The Srebf1 3′UTR has a potential binding site for miR-33 in many species (TargetScan; http://www.targetscan.org; Fig. 5b). Overexpression of miR-33 reduced the luciferase activity of a reporter gene fused with Srebf1 3′UTR sequences from humans and mice (Fig. 5c). Moreover, miR-33 decreased luciferase activity dose-dependently, whereas miR-146a, which has no binding site in the Srebf1 3′UTR, could not (Fig. 5d). Mutation in this binding site abolished the reduction of luciferase activity in 293T cells (Fig. 5e). The same results were also obtained in COS-7 cells (Supplementary Fig. S3b, c). We also measured the activity of SREBP-1 by sterol regulatory element (SRE) and fatty acid synthase (FAS) promoter reporter analysis by the use of Srebf1 with or without the 3′UTR. Luciferase activity of the SRE and FAS reporter genes was significantly reduced by miR-33 expression when Srebf1 with the 3′UTR was present. This reduction was not observed in the experiments conducted with Srebf1 without the 3′UTR (Fig. 5f,g). Overexpression of miR-33 reduced protein levels of SREBP-1 and ABCA1 but not of IRS-2 in HepG2 cells (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. S4a). The decrease in SREBF1 expression was mainly caused by reduction in SREBF1c (Supplementary Fig. S4b). Overexpression of miR-33 also reduced the protein levels of SREBP-1 and ABCA1 but not of IRS-2 in miR-33+/+ primary hepatocytes (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. S4c). It was confirmed that miR-33−/− mice had higher protein expression levels of SREBP-1 and ABCA1 but not of IRS-2 (Fig. 5h and Supplementary Fig. S4d). We measured the expression levels of lipogenic genes in the primary hepatocyte transduced with miR-33 or the control. As shown in Supplementary Fig. S4e, expression levels of Srebf1, Abca1 and several lipogenic genes were downregulated. Moreover, Srebf1, Abca1 and several lipogenic genes were upregulated in miR-33−/− primary hepatocytes compared with miR-33+/+ primary hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. S4f). SREBP-1 levels were further enhanced in miR-33−/− mice fed HFD (Supplementary Fig. S5a). We also measured the levels of AMPKα, previously described as a potential miR-33 target, but we could not detect any difference between miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S5b). We further checked whether PPAR-γ is regulated by miR-33 in primary hepatocytes. Overexpression of miR-33 did not change the protein expression level of PPAR-γ after transduction in HepG2 cells (Supplementary Fig. S5c) and primary hepatocytes (Supplementary Fig. S5d), and found non-enhancement in miR-33−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S5d). Moreover, we conducted peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor response elements (PPRE)-driven luciferase assay in HepG2 cells. No difference was observed in PPRE activity in control and miR-33 transduced cells with or without PPAR ligand pioglitazone (Supplementary Fig. S5e). Therefore, these results indicate that Pparg is not a direct target of miR-33.

Figure 5. Srebf1 is a miR-33 target gene.

(a) Relative changes in lipid metabolism-related genes in the livers of miR-33−/− mice compared with miR-33+/+ mice fed NC at 16 weeks of age. (n=5–8 each,*P<0.05 in Student’s t-test). (b) Conservation of miR-33 target regions in the 3′UTR of Srebf1. Underlined sequences are the potential binding site of miR-33 seed sequences. * indicates the conservation among spieces. (c) 3′UTR reporter assay used to verify the target. Luciferase reporter activity of human and mouse SREBP-1 gene 3′UTR constructs in 293T cells overexpressing miR-control (miR-Con) and miR-33 (n=4 each, *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 in Student’s t-test). (d) miR-33 dose-dependent changes in luciferase reporter activity of mouse Srebf1 3′UTR construct in 293T cells. miR-Con and miR-146a is used as a negative control (n=4 each, *P<0.05 and ***P<0.001 in one-way analysis of valiance test). (e) Luciferase reporter activity of the WT or mutant Srebf1 3′UTR at the potential miR-33 binding site in 293T cells (n=4 each, **P<0.01 in Student’s t-test). (f,g) Luciferase reporter activity of SRE-promoter (f) or FAS-promoter (g) in 293T cells. 293T cells were co-transfected with mouse Srebf1 with the full-length 3′UTR or without the 3′UTR, along with expression plasmids for miR-negative control, or miR-33. Values are the mean±s.e. (n=4 each, **P<0.01 versus miR-Con. ***P<0.001 versus miR-Con in one-way analysis of valiance test). (h) Western blotting analysis of SREBP-1, ABCA1, and IRS-2 in miR-33 transduced HepG2 cells and primary hepatocytes and hepatocytes prepared from miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice. Representative western blot images are shown (n=4). Values are the means±s.e.m.

SREBP-1 is regulated by endogenous changes in miR-33 in vitro

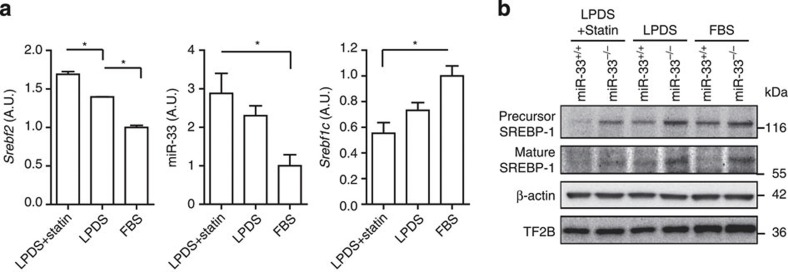

We further attempted to confirm whether the expression of SREBP-1 was affected by endogenous changes in miR-33 expression via modulating the cellular cholesterol level in primary hepatocytes. When the cells were depleted of sterols by prior incubation in medium containing lipoprotein-deficient serum (LPDS) with or without pitavastatin, mRNA levels of Srebf2 and miR-33 were significantly increased in parallel (Fig. 6a). In this situation, Srebf1c and protein levels of SREBP-1 were decreased in miR-33+/+ primary hepatocytes, whereas they were still elevated in miR-33−/− hepatocytes (Fig. 6b). There is a potential binding site of miR-33 in the 3′UTR of human SCAP. However, it is not conserved in mice and mRNA and protein levels of SCAP are the same in miR-33+/+ and miR-33−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S6a–c). Thus, the levels of precursor and mature forms of SREBP-1 are regulated in parallel.

Figure 6. SREBP-1 is regulated by endogenous changes in miR-33 in vitro.

(a) RNA expression levels in Srebf2, miR-33 and Srebf1c in primary hepatocytes cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS or 5% LPDS with or without statin treatment. Values are the mean±s.e.m. (n=3 each for Srebf2 and Srebf1c, n=4–6 each for miR-33, *P<0.05 in one-way analysis of valiance test). (b) Protein levels of SREBP-1 in primary hepatocytes cultured in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS or 5% LPDS with or without statin treatment. Representative western blot images are shown (n=4).

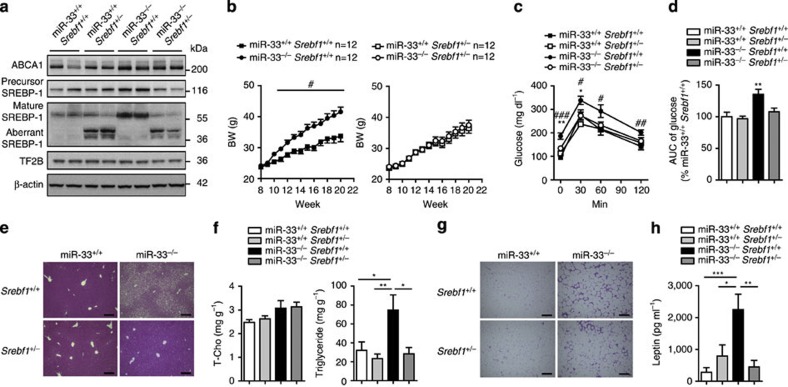

Reduction of SREBP-1 reverses fatty liver in miR-33-KO mice

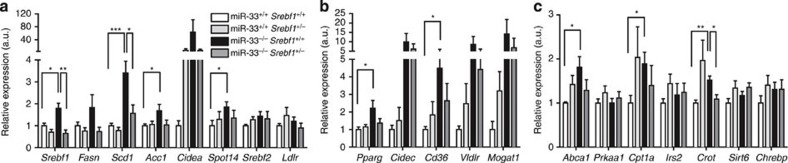

To elucidate the role of SREBP-1 in the phenotypic changes in miR-33−/− mice fed HFD, we generated miR-33−/− mice that have SREBP-1 expression levels similar to WT mice. As shown in Fig. 7a, protein levels of SREBP-1 are the same in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− and miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+ mice. Aberrant bands of SREBP-1 were observed in Srebf1-deficient mice (Fig. 7a and Supplementary Fig. S7a)15. mRNA levels of Srebf1 in these mice are shown in Fig. 8a. Because miR-33−/− mice showed positive palatability for HFD compared with miR-33+/+ mice (Fig. 4a), we analysed these four groups of mice under pair-feeding conditions. miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice received HFD in amounts that matched the rate of food intake of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+ mice. As shown in Fig. 7b’s left panel, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice gained significantly more weight than miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+ mice under these conditions. Therefore, the BW gain in miR-33−/− mice compared with miR-33+/+ mice is not caused by a change in food intake. The BW increase caused by miR-33 deficiency was abolished in a Srebf1+/− background (Fig. 7b right and Supplementary Fig. S7b). On the other hand, glucose tolerance was ameliorated in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− compared with miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice (Fig. 7c,d). There was no difference in BW or glucose tolerance among miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/− and miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice (Fig. 7b–d). Serum insulin levels were reduced in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice compared with miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice (Supplementary Fig. S7c, d). A striking difference was observed in the liver. Hepatic steatosis was reversed in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice compared with that in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice in both macro- and microscopic images and the liver triglyceride content of these mice was almost the same as that of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+ and miR-33+/+Srebf1+/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S7b and Fig. 7e,f). As shown in Fig. 7g, adipocyte size was partially reduced in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice compared with miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice and there were still many infiltrating cells in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice. Serum leptin levels also reduced to baseline levels in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice (Fig. 7h). These results indicate that obesity and hepatic steatosis were ameliorated in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice compared with miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice. There was no difference in the mRNA and protein levels of AMPKα and SIRT6, which are negative regulators of SREBP-1 and potential targets of miR-33, as shown in previous reports (Fig. 8c and Supplementary Fig. S7e). Finally, we examined the lipogenic gene profiles in the liver of these mice. As shown in Fig. 8a, the expression levels of Srebf1 were significantly increased in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice compared with miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+ mice, and this was reversed in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice. The same pattern was observed in Scd1. Although they were not statistically significant, the expression levels of Fasn, Acc1 and Pparg were reduced in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice compared with miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice (Fig. 8a,b). Serum data for these mice are summarized in Supplementary Table S4. Serum ALP levels were significantly elevated in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice, which was reversed in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice.

Figure 7. Reversal of hepatic steatosis by the reduction of SREBP-1 levels.

(a) Western blotting analysis of SREBP-1 and ABCA1 levels in the livers of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice. Representative western blot images are shown (n=4). (b) Serial changes in BW levels of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice fed HFD under pair-feeding condition (n=12 each). (c) Serial changes in glucose levels after intraperitoneal injection of glucose into miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice (n=11–12 each). *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 versus miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice. #P<0.05, ##P<0.01 and ###P<0.001 versus miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+ mice in one-way analysis of valiance test. (d) AUC of glucose levels in glucose tolerance tests in miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice (n=11–12 each). **P<0.01 versus miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice in one-way analysis of valiance test. (e) Representative microscopic images of the liver of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice fed HFD. Scale bars, 200 μm. (f) Cholesterol and triglyceride levels in the liver of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice fed HFD. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 in one-way analysis of valiance test. (g) Representative microscopic images of the adipose tissue of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice fed HFD. Scale bars, 200 μm. (h) Serum leptin levels of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice fed HFD. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 in one-way analysis of valiance test. Values are the means±s.e.m.

Figure 8. Relative mRNA expression levels of lipid metabolism-related genes.

(a) Srebfs and lipogenic genes. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 and ***P<0.001 in one-way analysis of valiance test (n=6–8 each). (b) Pparg and its downstream genes. *P<0.05 in one-way analysis of valiance test (n=6–8 each). (c) Other lipid metabolism-related genes. *P<0.05 and **P<0.01 in one-way analysis of valiance test (n=6–8 each). Relative values of lipid metabolism-related genes in the livers of miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+, miR-33+/+Srebf1+/−, miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/− Srebf1+/− mice fed with HFD. Values are the means±s.e.m.

Discussion

In the current study, we showed that obesity and hepatic steatosis are observed in miR-33-deficient mice at the age of 50 weeks or when fed HFD for 12 weeks. We demonstrated that miR-33 targets SREBP-1, and miR-33−/− mice had an enhanced expression of SREBP-1 in the liver. Study of miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice clearly showed that enhanced expression of SREBP-1 caused obesity and fatty liver in miR-33−/− mice (Supplementary Fig. S9a). These results indicate a previously unrecognized relationship between SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 through miR-33 (Supplementary Fig. S9b left).

Until now, there has been little evidence for an interaction between SREBP-1 and SREBP-2. It is known that in cholesterol-rich dietary conditions, SREBP-2 is downregulated at the cleavage level and SREBP-1c is transcriptionally activated through the activation of liver X receptors (LXRs) by the binding of oxysterols16,17,18,19. However, in sterol-depleted conditions, SREBP-2 is cleaved in the Golgi and the active N-terminal region translocates to the nucleus. Reduction in oxysterol levels leads to the inactivation of liver X receptors, which results in a decrease in SREBP-1c mRNA levels. Recently, it was shown that statin treatment induced hepatic miR-33 expression and at the same time decreased mRNA levels of miR-33 targets, including Abca1 (ref. 8), Abcb11 and Atp8b1 (ref. 20) in mice. Thus, not only the activation by proteolytic cleavage but also its transcriptional regulation of SREBP-2/miR-33 is important in vivo. Our data showed that miR-33 targeted the 3′UTR of Srebf1 and the upregulation of miR-33 by cholesterol depletion, considerably affecting the reduction of SREBP-1 expression. Therefore, based upon our findings that miR-33 regulates SREBP-1, miR-33 in the intron of SREBP-2 may amplify reduction in SREBP-1 levels in sterol-depleted conditions (Supplementary Fig. S9b centre). SREBP-1c activates transcription of genes involved in fatty acid and triglyceride synthesis, such as genes encoding acetyl-CoA carboxylase, fatty acid synthase and elovl-6 and stearoyl-CoA desaturase. Therefore, it is possible that in sterol-depleted conditions, acetyl-CoA is preferred as a substrate for cholesterol production and not for fatty acid production, through the upregulation of miR-33. On the other hand, in cholesterol-rich conditions, miR-33 levels decrease7 and its negative regulation of SREBP-1 may be reduced. Thus, in this situation, acetyl-CoA is preferred as a substrate for fatty acid production (Supplementary Fig. S9b right).

Previously, several different SREBP-1 transgenic (TG) mice have been produced. Liver-specific transgenic mice using a phosphoenolpyruvate carboxykinase (PEPCK) promoter indicated that the livers of the SREBP-1a TG mice (PEPCK-SREBP-1a) were massively enlarged, owing to the accumulation of triglycerides and cholesterol6. PEPCK-SREBP-1c TG livers were only slightly enlarged with a moderate increase in triglycerides but not cholesterol. It is interesting that epididymal fat weight was not increased in these mice6. However, other liver-specific TG mice lines overexpressing human SREBP-1a and SREBP-1c under the control of the albumin promoter showed a vast accumulation of lipids in the liver and obesity as observed in miR-33−/− mice21,22. Therefore, overexpression of SREBP-1 does not show consistent phenotypes and these changes may depend on the different promoters and expression patterns in organs of each transgenic line. Because SREBP-2 and miR-33 are expressed ubiquitously, miR-33−/− mice may have mildly enhanced expression of SREBP-1 throughout the body. Previously developed SREBP-1 TG mice do not resemble miR-33-deficient mice in this context. Thus, obesity and hepatic steatosis developed slowly when fed NC and became prominent when fed HFD. Although SREBP-1c-deficient mice do not show any change in BW, it is possible that some compensatory mechanisms may have occurred in these mice23. Because miR-33−/− mice showed a slight but significant increase in food intake when fed HFD, we conducted our crossbreeding experiments in pair-feeding conditions, which may have enabled us to clearly observe the changes. It is interesting that Ldlr−/− mice that received anti-miR-33 oligonucleotides once a week for 14 weeks gained weight although the change was not statistically significant24,25. Therefore, reduction of miR-33 levels is related to unwanted consequences such as elevated BW. It should also be noted that the expression of Pparg and its downstream signalling molecules were enhanced in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ mice compared with WT control mice26,27,28,29. Because these molecules are attenuated in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice, enhanced expression of Pparg may be related to the increase in SREBP-1 levels associated with miR-33 deficiency30,31.

The phenotype of miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice is not completely the same as that of WT mice, and this may be because of other miR-33 target genes. Abca1 mRNA expression and serum HDL-C levels still tend to be higher in miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− mice than those in miR-33+/+ Srebf1+/+ mice. Moreover, RIP140, another miR-33 target12,32, promotes the activity of NF-κB and upregulates the expression of genes implicated in inflammation such as TNFα and IL-6 in macrophages. Enhanced expression of RIP140 by miR-33 deficiency may affect the inflammatory conditions in adipose tissue.

It is important to explain why did not compare Srebf1+/+ with Srebf1+/− mice, but only compared miR-33−/−Srebf1+/+ and miR-33−/−Srebf1+/− in our experiments. The feedback system of SREBP-2 guarantees appropriate levels of cellular cholesterol. Meanwhile, excess glucose cumulatively activates SREBP-1 and increases triglyceride storage. The latter can be achieved by the fact that Srebf1 expression is enhanced by SREBP-1 itself and that cleavage of SREBP-1 is less sensitive to sterol-suppression than SREBP-2 (refs 33, 34, 35, 36). Therefore, we hypothesize that the differences in the expression of SREBP-1 and its downstream molecules between Srebf1+/+ and Srebf1+/− would be enhanced when SREBP-1 levels are increased by intercrossing with miR-33−/− mice. The Srebf1 levels are reduced in Lepob/ob × Srebf1+/− mice compared with Lepob/ob mice37. However, in Lepob/ob mice, the Srebf1 levels are not considerably enhanced in the liver, but are rather decreased in adipose tissue and the phenotype is different between Lepob/ob and miR-33−/− mice. Because Srebf1 may be more enhanced in miR-33−/− mice than Lepob/ob mice, intercrossing with Srebf1+/− had more effect in miR-33−/− mice than Lepob/ob mice. Similarly, phenotypic difference between Srebf1+/+ and Srebf1+/− mice with WT background may become small because Srebf1 is not enhanced. Although a threshold may exist for the SREBP-1 levels that distinguishes between the normal condition and lipotoxicity caused by positive energy imbalance, the threshold level of SREBP-1 can only be achieved by feeding the miR-33−/− Srebf1+/+ mice HFD or at an older age. This can also explain the fact that not much difference is observed between the Srebf1+/+ and Srebf1+/− mice at the basal condition. For this reason, one copy of Srebf1 can rescue the phenotype when miR-33 is absent. Recently, miRNAs have been recognized as therapeutic targets. It seems that it would be efficient to inhibit the function of a small number of miRNAs that have many different targets with similar functions at the same time. However, it is estimated that one miRNA may have hundreds of different target genes, and unpredicted results may be obtained by complete and long-term inhibition of an miRNA. It is also known that the results obtained by antisense oligonucleotide-based medicine are sometimes different from those obtained in miR-deficient mice. For example, the administration of an miR-21 antagomir prevented pressure-overload-induced cardiac hypertrophy and fibrosis in mice38; however, miR-21-deficient mice did not show any cardiac differences compared with WT mice under pressure overload39. As for miR-33, many target genes have been reported by computer algorithm and in vitro experiments such as luciferase-based 3′UTR analysis, only some of which show enhanced expression in miR-33-deficient mice.

A recent report indicated that the inhibition of miR-33a/b in non-human primates increases plasma HDL-C and lowers very-low-density lipoprotein triglycerides40. The authors showed a 50% decrease in SREBF1 mRNA and protein in anti-miR-33-treated monkeys at 12 weeks. They speculated that the decrease in SREBP-1 may result from the derepression of negative regulators of this pathway such as AMPK, which is targeted by miR-33. They actually observed an increase in AMPK (PRKAA1) mRNA levels. However, there was no change in AMPKα levels in our experiment, and this point should be clarified in future experiments. It is true that in humans, and not in rodents, there is miR-33b in SREBF1. Because miR-33a and miR-33b have the same seed sequence, their targets would be the same. This may explain the differences in AMPKα levels. Further studies may be required to clarify whether there is autoregulation of SREBP-1 by miR-33b. In contrast, the experiment on monkeys was designed to administer antisense miR-33 for a limited time period. In the present study, we demonstrated that miR-33 deficiency serves to raise SREBP-1, increase fatty acid synthesis and promote fatty acid accumulation in the body. Therefore, long-term therapeutic modulation of miR-33 to cure metabolic diseases requires caution for obesity and related diseases, as miRNAs have potentially many target genes and we cannot detect all of them by computer analysis. Moreover, many genes are affected by these secondary or tertiary target genes. Careful observation of miR-deficient mice enables us to detect overall functions of miRNAs in vivo.

In conclusion, these results unravel a previously unrecognized interaction between SREBP-1 and SREBP-2 by the way of miR-33. It will be important to establish the tissue- and time-specific regulation of miR-33 to avoid unexpected side effects.

Methods

Materials

The antibodies used were anti-ABCA1 (NB400-105) (Novus Biologicals, Littleton, CO, USA), anti-GAPDH (14C10; no. 2118S), anti-IRS-2 (no. 4502S), anti-AMPKα (no. 2532), anti-SIRT6 (D8D12; no. 12486) (Cell Signaling Technology, Beverly, MA, USA), anti-β actin (AC-15; A5441, Sigma-Aldrich, St Louis, MO, USA), anti-SREBP-1 (sc-13551, sc-8984), anti-TF2B (sc-225), anti-PPARγ (sc-7273), anti-SCAP (sc-48671) (Santa Cruz Biotechnology, California, USA), antibodies. Anti-rabbit, anti-mouse and anti-goat IgG HRP-linked antibodies were purchased from GE Healthcare (Amersham, UK).N-acetyl-leu-leu-norleucinal (Calpain inhibitor; ALLN) and Complete Mini (Protease inhibitor cocktail) were from Roche. Pitavastatin (NK-104) was kindly provided by Kowa (Japan). PPRE-luciferase promoter plasmid (PPRE-luc) was kindly gifted by Dr Kelly-DP. FAS-luciferase promoter plasmid (FAS-luc) was obtained from Addgene. SRE-luciferase promoter plasmid (SRE-luc) was from Dr Yahagi-N. Mouse Srebf1 was obtained from the FANTOM (functional annotation of the mouse) full-length mouse cDNA clone set, and Mouse Srebf1 with or without the 3′UTR was cloned into pcDNA3.1.

Cell culture

HepG2 cells were cultured Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s medium (DMEM; Nacalai Tesque, Japan) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Mouse primary hepatocytes were obtained from male miR-33+/+ or miR-33−/− mice at 8–10 weeks of age by the two-step collagenase perfusion method41. In brief, hepatocyte suspensions were obtained by passing collagenase type II (Gibco BRL, Life Technologies Inc., Rockville, MD, USA) digested liver through a 70 μm cell strainer, followed by centrifugation to collect the mature hepatocytes. After isolation, hepatocytes were resuspended in DMEM supplemented with 5% FBS, and seeded on collagen type I-coated dishes (Iwaki Asahi Glass Co. Ltd., Japan) at a density of 7 × 104 cells ml−1. After incubation for 24 h, cells were used for experiments. For sterol-depleted experiments, cells were washed twice with DMEM without FBS two times and switched to DMEM containing 5% LPDS (Sigma-Aldrich) with or without pitavastatin (1 μM).

Generation of miR-33−/− Srebf1 +/− mice

To obtain reduced levels of SREBP-1 in miR-33-deficient mice (miR-33−/−Srebf1+/−), miR-33−/− mice were mated with Srebf1+/− mice, which were a kind gift from Dr Shimano15. After being weaned at 4 weeks of age, mice were fed NC containing 4.5% fat until 8 weeks of age, and then switched to HFD (D12451; 45% fat by kcal; Research Diet Inc. New Brunswick, NJ, USA) or kept on NC for the next 12 weeks. All of the experimental protocols were approved by the Ethics Committee for Animal Experiments of Kyoto University. Primers for genotyping were as follows.

WT/KO (miR-33) sense; GGCACTACTTCTGATCCTTC

WT (miR-33) antisense; CAACTACAATGCACCACAGCTG

KO (miR-33) antisense; TTGGGATCCAGAATTCGTGATTAA

WT (Srebf1) sense; TGTGTCTGACCTGCAATCCT

WT (Srebf1) antisense; AGGCCAACACTAGTAGTCCATTG

KO (Srebf1) sense; AGGATCTCCTGTCATCTCACC

KO (Srebf1) antisense; GCCAACGCTATGTCCTGATA

Western blotting

Western blotting was performed using standard procedures as described previously42. For cell experiments, ALLN (12.5 μg ml−1) was added to the cells 2 h before collection. Samples were lysed in lysis buffer consisting of 100 mM Tris-HCl, pH 7.4, 75 mM NaCl and 1% Triton X-100 (Nacalai Tesque). The lysis buffer was supplemented with complete mini protease inhibitor (Roche), ALLN (25 μg ml−1), 0.5 mM NaF and 10 μM Na3VO4 just before use. Nuclear protein was extracted using the CelLytic NuCLEAR Extraction Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. The protein concentration was determined using a bicinchoninic acid (BCA) protein assay kit (Bio-Rad). All samples (20 μg of protein) were suspended in lysis buffer, fractionated using NuPAGE 4–12% Bis-Tris (Invitrogen) gels and transferred to a Protran nitrocellulose transfer membrane (Whatman). The membrane was blocked using 1 × phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) containing 5% non-fat milk for 1 h and incubated with the primary antibody (anti-ABCA1; 1:1,000, anti-ABCG1; 1:1,000, anti-IRS-2; 1:500, anti-AMPKα; 1:1,000, anti-SREBP-1; 1:250 (Supplementary Fig. S10), anti-TF2B; 1:1,000, anti-PPARγ; 1:250, anti-β actin; 1:3,000, anti-GAPDH; 1:3,000, anti-SIRT6; 1:1,000 and anti-SCAP; 1:200) overnight at 4 °C. Following a washing step in PBS-0.05% Tween 20 (0.05% T-PBS), the membrane was incubated with the secondary antibody (anti-rabbit, anti-mouse or anti-goat IgG HRP-linked; 1:2,000) for 1 h at 4 °C. The membrane was then washed in 0.05% T-PBS and detected by ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (GE Healthcare), using an LAS-1000 system (Fuji Film). Full-length images on immunoblots are shown in Supplementary Figs S11–S13.

RNA extraction and qRT–PCR

Total RNA was isolated and purified using TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche), and cDNA was synthesized from 1 μg of total RNA using the Transcriptor First Strand cDNA Synthesis Kit (Roche) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. For quantitative RT–PCR, specific genes were amplified by 40 cycles using SYBR™ Green PCR Master Mix (Applied Biosystems). Expression was normalized to the housekeeping gene β-actin. Gene-specific primers are listed in Supplementary Table S1.

Quantitative PCR for miRNAs

Total RNA was isolated using TriPure Isolation Reagent (Roche). miR-33 was measured in accordance with the TaqMan MicroRNA assays (Applied Biosystems) protocol, and the products were analysed using a thermal cycler (ABI Prism7900HT sequence detection system). Samples were normalized by U6 snRNA expression.

Measurement of fatty acid synthesis

Following 4 h of fasting, mice were intraperitonially injected with 10 μCi [1-14C]-sodium acetate (PerkinElmer Co., Ltd.). Male mice at 10 weeks of age were sacrificed 30 min after injection and livers were rinsed in ice-cold 1 × PBS. Liver samples were saponified by heating in 3 ml of 30% KOH (w/v) at 70 °C for 15 min, followed by the addition of 3 ml of 95% ethanol (v/v) and continued heating at 70 °C for a further 2 h. Saponified fatty acids were acidified with 3 ml of 9 M H2SO4 and extracted with petroleum ether13,14.

Dual luciferase assays

Full-length PCR fragments of the 3′UTR of SREBF1 were amplified from human or mouse cDNAs and subcloned downstream of a CMV-driven Firefly luciferase cassette in a pMIR-REPORT vector (Ambion). To create WT or mutant 3′UTR luciferase reporter genes, a fragment of the Srebf1 3′UTR as follows was inserted into a pMIR-REPORT vector:

Wild type;

CTTCCAAAACAATCGTGGTATCTTTATTGACTTTTTTTTTTCTGAATGCAATGACTGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTAAC

Mutant;

CTTCCAAAACAATCGTGGTATCTTTATTGACTTTTTTTTTTCTGATACGTATGACTGTTTTTTTTTTTTTTAAC

For SRE and FAS promoter assay, 293T cells were co-transfected with mouse Srebf1 with full-length 3′UTR or without 3′UTR, along with expression plasmids for miR-control (negative control), or miR-33. An internal control reporter, Renilla reniformis luciferase, driven by the thymidine kinase (TK) promoter (pRL-TK: Promega) was also co-transfected to normalize the transfection efficiency. Luciferase activities were measured using a dual luciferase kit (PicaGene dual kit, Toyo Ink Co.). The relative luciferase activity of each construct (arbitrary unit) was reported as the fold induction.42

Lentivirus production and DNA transduction

We produced lentiviral stocks in 293FT cells in accordance with the manufacturer’s protocol (Invitrogen). In brief, virus-containing medium was collected 48 h post transfection and filtered through a 0.45-μm filter. One round of lentiviral infection was performed by replacing the medium with virus-containing medium (containing 8 μg of Polybrene per ml), followed by centrifugation at 2,500 rpm for 30 min at 32 °C. Cells were used for analysis 3 days after DNA transduction.

IPGTT and insulin tolerance test

For IPGTT, after overnight fasting, male mice at 20 or 50 weeks of age were injected with 1.5 g kg−1 glucose intraperitoneally. For insulin tolerance test, after a 4-h fast, mice were injected intraperitoneally with insulin (0.75 u kg−1 and 1.0 u kg−1 for NC and HFD, respectively, Humulin R; Eli Lilly Japan KK). Blood was obtained from the orbital vein and glucose levels were measured using a glucose sensor.

Measurement of serum insulin and leptin levels

We quantified serum levels of insulin and leptin in male mice at 20 weeks of age using an ELISA assay kit for mouse insulin and leptin in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions (Shigayagi Co. Ltd, Shibukawa, Japan).

Biochemical analysis of serum

After mice (male at 20 or 50 weeks of age) were fasted for 4–6 h, blood was obtained from the inferior vena cava of anaesthetised mice, and serum was separated by centrifugation at 4 °C and stored at −80 °C. Biochemical data were measured by standard methods using a Hitachi 7180 Auto Analyzer (Nagahama Life Science Laboratory, Nagahama, Japan).

Measurement of cholesterol and triglyceride in the liver

Lipids in the liver were extracted by the Folch procedure43. In brief, lipids were extracted by addition of ice-cold MeOH followed by the addition of ice-cold CHCl3. High purity water was added and the sample kept on ice for an additional 10 min with occasional mixing. The sample was centrifuged for 5 min at 2,000 g and the upper (aqueous) phase was removed and reextracted by addition of ice-cold CHCl3:MeOH (2:1, v/v) as above. The upper phase was discarded and both organic phases were combined, dried under nitrogen stream. Lipids were quantified using standard enzymatic colorimetric methods (Sky Light Biotech, Akita, Japan).

Measurement of fat body mass by CT

CT scans were obtained and fat body mass and lean body mass were analysed using a Lathea LTC-100 (Aloka, Tokyo, Japan) under pentobarbital anaesthesia.

DNA microarray analysis

Five liver RNA samples from miR-33+/+ or miR-33−/− male mice at 16 weeks of age receiving NC were pooled and analysed using a DNA microarray (3D-Gene Mouse Oligo chip 24 k, Toray, Tokyo, Japan).

Pair feeding

Every other day, male mice received the same amount of food consumed by miR-33+/+Srebf1+/+ mice (WT) on the previous 2 days, from 8 to 20 weeks of age.

Assessment of metabolic rate and activity

Oxygen consumption and activity of male mice at 16 weeks of age were measured with an indirect calorimetric system. In brief, room air was pumped through an acrylic metabolic chamber, and the expired gas was filtered through thin cotton, dried and subjected to gas analysis (model RL-600; Alco System, Tokyo, Japan)44.

Statistics

Data are presented as means±s.e.m. Statistical comparisons were performed using unpaired two-tailed Student’s t-tests or a one-way analysis of variance with the Bonferonni post hoc test where appropriate, with a probability value of <0.05 taken to indicate significance.

Author contributions

T.H., T.N. and K.O. designed the project; T.H., T.N., O.B., Y.K., T.N., M.N., S.U., M.I., M.S. and S.M. performed experiments; T.H., T.N., N.Y., H.S., K.I., H.M., T.M., K.H., N.K., M.Y., T.K., T.K. and K.O. analysed and interpreted data; N.Y. and H.S. contributed materials; and T.H., T.N. and K.O. prepared the manuscript.

Additional information

How to cite this article: Horie, T. et al. MicroRNA-33 regulates sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 expression in mice. Nat. Commun. 4:2883 doi: 10.1038/ncomms3883 (2013).

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figures S1-S13 and Supplementary Tables S1-S4

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by grants from the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science, and by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science, and Technology of Japan (to T. Kimura, T. Kita, K.H., T.H., and K.O.), by Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research on Innovative Areas ‘Crosstalk between transcriptional control and energy pathways, mediated by hub metabolites’(3307), from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology of Japan (to K.O.), by Otsuka Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. – Kyoto University SRP Program (to T. Kimura, T. Kita, M.Y., T.H. and K.O.), Banyu Life Science Foundation International, Takeda Memorial Foundation, Suzuken memorial foundation, Sakakibara memorial foundation (to T.H.) and by grants from ONO Medical Research Foundation, the Cell Science Research Foundation, Daiichi-Sankyo Foundation of Life Science, and Takeda Memorial Foundation (to K.O.).

References

- Brown M. S. & Goldstein J. L. The SREBP pathway: regulation of cholesterol metabolism by proteolysis of a membrane-bound transcription factor. Cell 89, 331–340 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yokoyama C. et al. SREBP-1, a basic-helix-loop-helix-leucine zipper protein that controls transcription of the low density lipoprotein receptor gene. Cell 75, 187–197 (1993). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimomura I., Shimano H., Horton J. D., Goldstein J. L. & Brown M. S. Differential expression of exons 1a and 1c in mRNAs for sterol regulatory element binding protein-1 in human and mouse organs and cultured cells. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 838–845 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espenshade P. J. & Hughes A. L. Regulation of sterol synthesis in eukaryotes. Annu. Rev. Genet. 41, 401–427 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimano H. SREBPs: physiology and pathophysiology of the SREBP family. FEBS J 276, 616–621 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimano H. et al. Isoform 1c of sterol regulatory element binding protein is less active than isoform 1a in livers of transgenic mice and in cultured cells. J. Clin. Invest. 99, 846–854 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. J. et al. MiR-33 contributes to the regulation of cholesterol homeostasis. Science 328, 1570–1573 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Najafi-Shoushtari S. H. et al. MicroRNA-33 and the SREBP host genes cooperate to control cholesterol homeostasis. Science 328, 1566–1569 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquart T. J., Allen R. M., Ory D. S. & Baldan A. miR-33 links SREBP-2 induction to repression of sterol transporters. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 12228–12232 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie T. et al. MicroRNA-33 encoded by an intron of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 2 (Srebp2) regulates HDL in vivo. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 107, 17321–17326 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. J. et al. Antagonism of miR-33 in mice promotes reverse cholesterol transport and regression of atherosclerosis. J. Clin. Invest. 121, 2921–2931 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie T. et al. MicroRNA-33 deficiency reduces the progression of atherosclerotic plaque in ApoE(−/−) mice. J. Am. Heart Assoc. 1, e003376 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li T., Francl J. M., Boehme S. & Chiang J. Y. Regulation of cholesterol and bile acid homeostasis by the CYP7A1/SREBP2/miR-33a axis. Hepatology 58, 1111–1121 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stansbie D., Brownsey R. W., Crettaz M. & Denton R. M. Acute effects in vivo of anti-insulin serum on rates of fatty acid synthesis and activities of acetyl-coenzyme A carboxylase and pyruvate dehydrogenase in liver and epididymal adipose tissue of fed rats. Biochem. J. 160, 413–416 (1976). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimano H. et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 as a key transcription factor for nutritional induction of lipogenic enzyme genes. J. Biol. Chem. 274, 35832–35839 (1999). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheng Z., Otani H., Brown M. S. & Goldstein J. L. Independent regulation of sterol regulatory element-binding proteins 1 and 2 in hamster liver. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 92, 935–938 (1995). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeBose-Boyd R. A., Ou J., Goldstein J. L. & Brown M. S. Expression of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c (SREBP-1c) mRNA in rat hepatoma cells requires endogenous LXR ligands. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 98, 1477–1482 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Repa J. J. et al. Regulation of mouse sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1c gene (SREBP-1c) by oxysterol receptors, LXRalpha and LXRbeta. Genes Dev. 14, 2819–2830 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yoshikawa T. et al. Identification of liver X receptor-retinoid X receptor as an activator of the sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1c gene promoter. Mol. Cell. Biol. 21, 2991–3000 (2001). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allen R. M. et al. miR-33 controls the expression of biliary transporters, and mediates statin- and diet-induced hepatotoxicity. EMBO Mol. Med. 4, 882–895 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotzka J. et al. Preventing phosphorylation of sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1a by MAP-kinases protects mice from fatty liver and visceral obesity. PLoS One 7, e32609 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knebel B. et al. Liver-specific expression of transcriptionally active SREBP-1c is associated with fatty liver and increased visceral fat mass. PLoS One 7, e31812 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimano H. et al. Elevated levels of SREBP-2 and cholesterol synthesis in livers of mice homozygous for a targeted disruption of the SREBP-1 gene. J. Clin. Invest. 100, 2115–2124 (1997). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquart T. J., Wu J., Lusis A. J. & Baldan A. Anti-miR-33 therapy does not alter the progression of atherosclerosis in low-density lipoprotein receptor-deficient mice. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 455–458 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Naar A. M. Anti-atherosclerosis or no anti-atherosclerosis: that is the mir-33 question. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 33, 447–448 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y. L. et al. Aberrant hepatic expression of PPARgamma2 stimulates hepatic lipogenesis in a mouse model of obesity, insulin resistance, dyslipidemia, and hepatic steatosis. J. Biol. Chem. 281, 37603–37615 (2006). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. J. et al. Nuclear receptor PPARgamma-regulated monoacylglycerol O-acyltransferase 1 (MGAT1) expression is responsible for the lipid accumulation in diet-induced hepatic steatosis. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 109, 13656–13661 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou L. et al. Cidea promotes hepatic steatosis by sensing dietary fatty acids. Hepatology 56, 95–107 (2012). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran-Salvador E. et al. Role for PPARgamma in obesity-induced hepatic steatosis as determined by hepatocyte- and macrophage-specific conditional knockouts. Faseb. J. 25, 2538–2550 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim J. B., Wright H. M., Wright M. & Spiegelman B. M. ADD1/SREBP1 activates PPARgamma through the production of endogenous ligand. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 95, 4333–4337 (1998). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fajas L. et al. Regulation of peroxisome proliferator-activated receptor gamma expression by adipocyte differentiation and determination factor 1/sterol regulatory element binding protein 1: implications for adipocyte differentiation and metabolism. Mol. Cell. Biol. 19, 5495–5503 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ho P. C., Chang K. C., Chuang Y. S. & Wei L. N. Cholesterol regulation of receptor-interacting protein 140 via microRNA-33 in inflammatory cytokine production. Faseb. J. 25, 1758–1766 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horton J. D., Goldstein J. L. & Brown M. S. SREBPs: activators of the complete program of cholesterol and fatty acid synthesis in the liver. J. Clin. Invest. 109, 1125–1131 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eberle D., Hegarty B., Bossard P., Ferre P. & Foufelle F. SREBP transcription factors: master regulators of lipid homeostasis. Biochimie 86, 839–848 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dif N. et al. Insulin activates human sterol-regulatory-element-binding protein-1c (SREBP-1c) promoter through SRE motifs. Biochem. J. 400, 179–188 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasty A. H. et al. Sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 is regulated by glucose at the transcriptional level. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 31069–31077 (2000). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yahagi N. et al. Absence of sterol regulatory element-binding protein-1 (SREBP-1) ameliorates fatty livers but not obesity or insulin resistance in Lep(ob)/Lep(ob) mice. J. Biol. Chem. 277, 19353–19357 (2002). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thum T. et al. MicroRNA-21 contributes to myocardial disease by stimulating MAP kinase signalling in fibroblasts. Nature 456, 980–984 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patrick D. M. et al. Stress-dependent cardiac remodeling occurs in the absence of microRNA-21 in mice. J. Clin. Invest. 120, 3912–3916 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rayner K. J. et al. Inhibition of miR-33a/b in non-human primates raises plasma HDL and lowers VLDL triglycerides. Nature 478, 404–407 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seglen P. O. Preparation of isolated rat liver cells. Methods Cell Biol. 13, 29–83 (1976). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horie T. et al. Acute doxorubicin cardiotoxicity is associated with miR-146a-induced inhibition of the neuregulin-ErbB pathway. Cardiovasc. Res. 87, 656–664 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Folch J., Lees M. & Sloane Stanley G. H. A simple method for the isolation and purification of total lipides from animal tissues. J. Biol. Chem. 226, 497–509 (1957). [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hotta Y. et al. Fibroblast growth factor 21 regulates lipolysis in white adipose tissue but is not required for ketogenesis and triglyceride clearance in liver. Endocrinology 150, 4625–4633 (2009). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figures S1-S13 and Supplementary Tables S1-S4