Abstract

Objective

The internet is a valuable resource for accessing health information and support. We are developing an instrument to assess the effects of websites with experiential and factual health information. This study aimed to inform an item pool for the proposed questionnaire.

Methods

Items were informed through a review of relevant literature and secondary qualitative analysis of 99 narrative interviews relating to patient and carer experiences of health. Statements relating to identified themes were re-cast as questionnaire items and shown for review to an expert panel. Cognitive debrief interviews (n = 21) were used to assess items for face and content validity.

Results

Eighty-two generic items were identified following secondary qualitative analysis and expert review. Cognitive interviewing confirmed the questionnaire instructions, 62 items and the response options were acceptable to patients and carers.

Conclusion

Using a clear conceptual basis to inform item generation, 62 items have been identified as suitable to undergo further psychometric testing.

Practice implications

The final questionnaire will initially be used in a randomized controlled trial examining the effects of online patient's experiences. This will inform recommendations on the best way to present patients’ experiences within health information websites.

Keywords: E-health, Patients’ experiences, Information, Secondary data analysis, Cognitive debrief interviews

1. Introduction

UK health policy acknowledges the value of patient choice, self-care, and patient and public involvement [1–3]. In order to help people realize these ideals, the internet can be a valuable and accessible information resource. Research carried out by the Oxford Internet Institute has shown 71% of the UK population have sourced health information online [4]. Health-related websites have conventionally presented information in the style of scientific facts; however, experiences of health are increasingly exchanged by patients online and patients’ experiences are often included on health websites. People's use of the web for sharing, collaboration and connecting gained pace with the advent of Web 2.0 and the use of platforms for social networking, personal blogs and multimedia [5].

Peer-to-peer information and support can act as a supplement to information provided by healthcare professionals. This ‘experiential’ information is now routinely incorporated into mainstream health websites and can be accessed on ‘NHS Choices’, national and local charitable groups and private company websites. U.S. research has found one in five internet users went online to find people like them, with the number rising for those with a chronic condition. Caregivers, those experiencing a medical crisis in the past year and groups experiencing change in their physical health (for example, changes in weight or smoking behavior) were also particularly likely to use peer-to-peer resources [6].

With the increase in internet use for health, however, the importance of establishing the impact health websites can have on the user becomes critical. It is important for health website developers and health care providers to understand the potential effects of the information provided through their websites and to understand the effect experiential information and internet discussion forums may have on users. In order to accurately evaluate the impact a website has on the user a valid and reliable instrument is needed. This paper demonstrates the use of secondary analysis and patient–expert refinement in the development of an item pool for an instrument to measure the impact of exposure to health websites.

Health-related measurement scales require a clear conceptual basis to inform item generation [7,8]. Involving the patient in the development of a self-reported questionnaire is important as they may highlight issues not found in the literature or considered irrelevant by health care professionals. Terminology can also become outdated or be interpreted differently among various populations and user involvement can ensure that a measures questions and response scales are understandable to patients [9–11]. It is widely acknowledged that the conceptual underpinnings of a measure must be explicit and empirically based [7–9,12,13]. With this in mind, we outline steps taken in the development of a generic item pool relating to the proposed instrument.

2. Methods

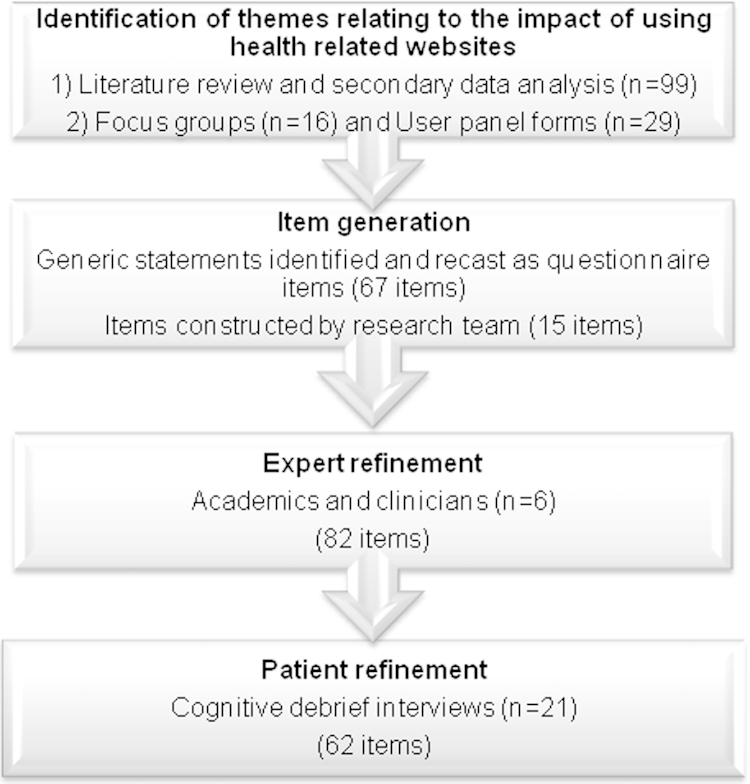

Several steps were taken in order to construct items relevant to the effects of exposure to health websites (see Fig. 1). Items were primarily informed through a review of relevant literature [14] and secondary qualitative analysis of narrative interviews relating to patients’ and carers’ experiences. Statements were selected to represent themes identified in the literature review and recast as questionnaire items. A period of item refinement through patient and expert review followed.

Fig. 1.

Steps taken to develop item pool.

2.1. Secondary data analysis

Secondary data analysis, the reuse of data originally collected fo another research purpose [15], was carried out using interview transcripts held in the Oxford Health Experiences Research Group (HERG) archives. At the time of the study the HERG database included 60 narrative interview collections relating to patient and carer health experiences. HERG interviews are recorded using digital video and/or audio recording equipment and collections typically aim to achieve a sample with ‘maximum variation’. The HERG collections have been used for a number of other secondary analysis studies, including studes of how people talk about using the internet [16,17].

HERG interviews are conducted using an open ended narrative structure followed by a semi-structured interview [18]. Participants are asked about sources of health information or support, including the internet. Interview transcripts were reviewed to identify incidences where participants discussed having used websites which contained factual health information or experiential information. Of the 203 interviews sampled, the analysis reported here was based upon 99 transcripts where use of the internet was discussed in some detail (n = 99, 48.8%).

Access to the interview archive meant that our analysis was not limited to a population with a specific condition, demographic profile or role (i.e. carer or patient). Rather, a range of socio-demographic variables and illness categories were chosen to compare and contrast effects amongst conditions.

2.1.1. Analysis

Interview transcripts were analyzed using a modified version of the “Framework” method, an analytical approach developed by the UK based National Centre for Social Research [19]. Framework analysis is systematic and involves five stages: (1) familiarization with the data gathered; (2) identifying a thematic framework; (3) indexing the transcripts according to the thematic framework; (4) charting the data to allow within-case and between-case comparison; and (5) mapping and interpretation of data [20–22]. Many of the themes that were expected to be raised during analysis had been identified in the literature review [14] which explored the potential effects of seeing and sharing experiences online. The secondary analysis sought to gain a deeper understanding of existing (‘anticipated’) themes found in the literature whilst being mindful of any new (‘emergent’) concepts which arose.

Indexing took place within NVIVO and charting was carried out using EXCEL. Charting the data involved lifting the data verbatim to facilitate the use of participants own words when forming items. Themes were checked for applicability across three condition groups and three different types of health websites to ensure its suitability for inclusion in a generic item pool.

2.2. Confirmatory sources

Two sources of data were used to check the themes identified for the measure: (1) Focus group transcripts (n = 16) from research carried out on trust and online health information in Northumbria University (see [23] for methodology) and; (2) Comment forms (n = 29) completed by members of an internet user panel consisting of lay persons using local primary health care services. The user panel comment forms asked people to list the potential advantages and disadvantages of using the internet for health information. Comments were collated in a single document to compare issues raised with the themes previously identified. Using more than one data source provided ‘data triangulation’ to enhance rigor within the research [24].

2.3. Representation of themes and identifying generic statements

Each theme identified through the analysis was represented by relevant statements (in the form of verbatim quotes) from the HERG transcripts. Statements were arranged according to the theme in a tabulated summary which identified the health condition from where it originated. This allowed each statement to be traced to its origin throughout the iterative process. Statements which could be answered by people across health conditions (i.e. generic statements) were identified. The authors recast statements as questionnaire items and removed duplicate items.

2.4. Expert refinement

Items were reviewed by an advisory board consisting of six clinicians and academics with interests in the field of e-health. Reviewers were asked whether items were answerable to those exposed to websites containing: (1) experiential health information, (2) standard ‘facts and figures’ health information and; (3) patients online health forums. Reviewers were also asked to comment on whether items were suitable for individuals who were viewing a website which was aimed at: (1) long term conditions, (2) health promotion activities and; (3) carers. Reviewers were asked to flag items which they thought a person in the outlined criteria could not answer and to critique the items using guidance adapted from a questionnaire designer's tool [25].

2.5. Patient refinement

Cognitive interviewing, a qualitative method used find to out how respondents understand and answer structured questions was used to improve the validity and acceptability of items [26,27]. Men and women aged 18+ were recruited if they had a health condition or cared for someone who had a health condition. Participants were purposely selected to reflect a spectrum of health conditions and carers and were asked to spend 10–15 min browsing a relevant health website. A spectrum of website providers were incorporated: government websites (for example, NHS Choices), charity websites (for example, Health Talk Online) and commercial websites (for example, BootsWebMD). Websites were chosen to ensure the items were tested with experiential content and ‘facts and figures’ content. Websites were also chosen to incorporate features such as discussion boards, video clips and ratings. The ‘verbal probing’ method of cognitive interviewing was used giving respondents an opportunity to provide uninterrupted answers to the items, followed by a focused interview [26,28]. This method of interviewing queried a participant's understanding of an item and their interpretation of the instructions and response options [20].

2.5.1. Analysis

Items were checked for consistency of interpretation between participants and across health groups. Reoccurring problems with specific items or wording were highlighted. Analysis was carried out throughout the interview process so that problems identified could be revised and retested. Interviews were conducted until it was thought all potential problems with questionnaire completion had been identified, revised and retested.

2.6. Ethics

The HERG interview archive has approval from the interview respondents for secondary analysis. Ethical approval was obtained for cognitive testing through the University of Oxford Ethics Committee.

3. Results

3.1. Secondary data analysis sample

Ninety-nine participants, 28 (28.3%) men and 71 (71.7%) women, were included in the sample. All had used the internet in relation to a health issue. With the exception of four interviews conducted with couples and one interview with three young women, interviews were conducted on a one-to-one basis. Participants ranged from 15 to 80 years old and had a mean age of 35.0 years (SD 16.9). Carers accounted for 30.3% of the participants interviewed whilst the remaining 69.7% were interviewed about their own health. Of those who reported their ethnicity (n = 75), 90.7% were white. Table 1 shows further detail.

Table 1.

Participant distribution by gender and condition.

| Condition group | Male | Female | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| Long term condition (younger people) | 3 | 12 | 15 |

| Diabetes (younger people) | 5 | 14 | 19 |

| Depression (younger people) | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Parkinson disease (carers) | 2 | 4 | 6 |

| Motor neuron disease (carers) | 3 | 6 | 9 |

| Dementia (carers) | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Antenatal screening | 1 | 4 | 5 |

| Fetal abnormality | 5 | 8 | 13 |

| Menopause | 0 | 6 | 6 |

| Mental health: BME (carers) | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| Total | 28 | 71 | 99 |

Participants within the sample reported accessing health websites intermittently; frequency of use peaked according to key health events (such as diagnosis, or progression of an illness). Participants had used different resources (including conventional health websites, health discussion forums and blogs) and often combined the information they found online with advice from health care professionals. Participants differed in the amount of information they wanted to access; some avoided online sources which they thought might be upsetting or distressing.

3.1.1. Themes identified to inform the item pool

A literature review [14], which identified the potential effects of seeing and sharing experiences online, guided the identification of five themes. These five themes were found to be applicable to the impact of exposure to health websites containing scientific information and/or experiential information:

-

1)Information. Participants used websites to learn about their health and increase their knowledge on specific aspects of a condition. Participants used the internet to instantly access information and typically consulted multiple websites....we became experts on trisomies and all sorts of genetic disorders...it's wonderful now with the internet because you just dial up you know ‘genetics’, or ‘abnormalities’ and you just go on this journey and find out absolutely everything there is to know.... (Fetal abnormality) EAP32Although the internet was viewed as a valuable resource for instantly accessing information, participants sometimes reported difficulties making sense of the information they found online or knowing when to trust the information source. In addition to factual information, websites were also used for health related advice and tips:[Husband] was having trouble turning over in bed, you know, and somebody had written [online]... buy...satin sheets (Motor Neuron Disease-Carer) MND34

-

2)Feeling supported. Participants felt comforted and less anxious about symptoms when they discovered others had similar health experiences to them:... You start to think ‘What the hell's wrong with me, have I got some disease?’...Until I found the website and I read the forum and I thought ‘Jesus there's hundreds of women like me... this is quite normal’. (Menopause) MEN12Participants who had unpredictable symptoms in relation to their health, found websites helpful when they needed emotional support:...something happens and you can just dab into the Internet and just read somebody else's [experience]... It's instant reassurance.... (Long term conditions) CI28

A website which had a positive tone or interacting with people who had optimistic views helped some participants to foster a more hopeful outlook in relation to their health. Others however found it counterproductive to contrast their health with others. Some participants with depression, for example, found discussing sensitive issues could become upsetting.

-

3)

Relationships with others. Websites which incorporated comment fields, ratings or discussion forms reduced feelings of isolation and allowed participants to feel that others understood. Those who indicated they had a very active online presence (for example, through interacting regularly in discussion forums or email support groups) described feeling a sense of comradeship with other users. Some participants used discussion forums to offload concerns which they were unable to tell people in their everyday lives.

Using the internet had the potential to make offline relationships easier through providing a space where participants could vent their health concerns to people going through similar experiences and not burden friends or family. Websites could help participants to articulate what they were going through, and how they felt, to people in their everyday life. One man however, described feeling hurt when he read a post written by his partner on a discussion forum:.. she’d shared a feeling... and my initial reaction was, ‘Why the bloody hell can you share that with that person you don’t know, but you can’t share it with me?’.… (Ending pregnancy due to a fetal abnormality) EAP35 -

4)Experiencing health services. Participants sometimes consulted health websites when they were unsure whether and where to access appropriate health services. Before consulting health care professionals, participants talked about using the internet to find out what important questions they should ask in order to get the most out of a consultation. Going to a consultation ‘armed with information’ helped patients to be articulate and become more involved in health decisions. Participants became aware of potential treatments or ways in which they could manage their health:...after I’d first heard about [an insulin pump], I... looked on the Internet and spoke to people about the [insulin] pump...then I was bringing it up with my consultant at every appointment saying ‘This is going to be a good thing for me’. (Diabetes) DYP13

Participants used the internet after consultations in order to check, reconfirm or corroborate advice given by healthcare professionals.

-

5)Affecting behavior. Participants, particularly those with long term conditions, described wanting to know the short and long term consequences of their lifestyle and commitment to self-management in relation to their health. They implied that getting the right information could be motivational when managing their health.[I would like to see online]... complications for the person who hasn’t looked after themselves and the health benefits for the person who has looked after themselves. I think that sort of thing would be fairly useful and fairly motivational for someone who has got the condition (Diabetes) DYP36

Seeing the consequences of poor health management could be influential in their future health choices.

3.2. Confirmatory sources

Confirmatory data sources were reviewed in order to ensure that each theme identified had been fully explored and that no additional themes were evident. No further themes were identified, however, members of the user panel were concerned that people could become heavily reliant on relationships formed through health discussion forums and may become isolated from the ‘real’ (or offline) world. Whilst members of the user panel and participants in the Northumbria discussion groups acknowledged that consulting the internet could prevent unnecessary visits to the doctor, there were concerns that individuals might misunderstand online health information or be misled by inaccuracies in the content.

3.3. Representation of themes

Statements (376), in the form of verbatim quotes, representing the identified themes for the item pool were drawn from HERG transcripts. Generic statements (149) which could be answered by people across health conditions were identified by LK. Statements were recast as questionnaire items and reduced to 67 items in an iterative process involving all authors. In the absence of suitable verbatim statements, fifteen further items relating to the identified themes were constructed by the research team. See Table 2 for example items representing each theme.

Table 2.

Examples of items according to theme.

| Theme | Example item |

|---|---|

| (1) Information | I have learnt something new from this website. |

| (2) Feeling supported | I feel I have a lot in common with other people using this website. |

| (3) Relationships with others | This website gives me the confidence to explain my health concerns to others. |

| (4) Experiencing Health Services | This website raises questions I might ask a doctor or nurse. |

| (5) Affecting behavior | This website encourages me to take steps that could be beneficial to my health. |

3.4. Expert refinement

Minor amendments to the wording of the preamble and items were made in order to improve clarity following reviewers’ comments. Amendments were made to two items following reviewers concern that they were unsuitable for participants with low health literacy. Reviewers agreed that items covered the themes identified as relevant to the impact of exposure to health websites and that items were answerable across a range of health conditions and roles (i.e. by a patient or a carer).

3.5. Patient refinement

Participants (n = 21) were 6 men and 15 women with a mean age of 45 years old (SD16.2). Five were carers and 16 had a specific health condition. Three rounds of cognitive interviewing were carried out to ensure (1) the instructions were easy to understand and the rubric clearly indicated how participants were supposed to answer items, (2) participants found all items retained (62) relevant to the topic and acceptable to answer, (3) the response options were appropriate to the item stem and the response options adequately covered the potential range of agreement, and (4) the electronic format was appropriate for use among a range of participants with varying levels of computer proficiency. Twenty-nine items were deleted and nine items were added in total, leaving 62 items to enter psychometric testing. Emphasis was placed upon retaining a sufficient number of items to represent each of the five themes identified.

3.6. Final item pools

Following expert and patient refinement, two independent item pools were confirmed as suitable to enter psychometric testing. The first item pool contained 23 items asking respondents about their general attitudes toward health websites whilst the second item pool contained 39 items asking the respondent about their attitudes toward a specific health website. All items have a five point response scale (Strongly disagree–Strongly agree).

4. Discussion and conclusion

4.1. Discussion

Establishing a robust evidence base for the use of health websites is becoming increasingly important given that patients routinely turn to the web for information and support. This research developed items which will inform a new measure to evaluate the health related effects of websites and create a standardized method to compare health websites. Items constructed were checked for their applicability across long term conditions, health behaviors and carers and for websites featuring facts and figures, health experiences and discussion forums.

This paper documents the steps taken to inform items that may be included in the e-Health Impact Questionnaire. A recent literature review [14] relating to the potential effects of seeing and sharing experiences online and a secondary data analysis of interviews relating to experiences of health were used to generate a range of items. Five themes were identified as relevant to the impact of using health websites containing scientific information and to websites containing experiential information: (1) Information, (2) feeling supported, (3) relationships with others, (4) experiencing health services, and (5) affecting behavior. Confirmatory data sources were used to triangulate the findings. Comparing themes to issues raised in the focus group transcripts and user panel forms provided more depth in relation to negative aspects of using the internet, for example, becoming isolated from society through the overuse of discussion forums or misdiagnosing symptoms. Using a range of sources to identify and confirm themes provided strong evidence for their inclusion in the item pool.

After a period of item selection, the item pool was evaluated by experts in the area of e-health. Instructions, items, response options and the electronic format of the instrument were found to be acceptable to patients and carers through the use of cognitive interviews.

The methods used to inform item generation in this study reflect best practice guidelines in the initial stages of questionnaire development [9–11]. Gaining a rich and detailed understanding of the construct to be measured is best achieved from focused interviews with the relevant population. Whilst this is particularly relevant for condition specific measures however, this generic measure needed to be applicable to people over a range of health conditions and roles (i.e. patients and carers).

The opportunity to carry out secondary data analysis using a large interview archive which spanned a range of conditions was therefore particularly useful for the development of this item pool. However, analysis of secondary data can be restrictive in comparison to primary research where the interviewer can focus their questions on the issues of most interest to their own research agenda [15]. In some interviews the original reseracher had not probed into participants experiences of using health websites. Integrating secondary analysis of several, purposively selected collection of interviews with a conceptual literature review and using confirmatory sources of data was therefore vital in ensuring all potential themes were investigated thoroughly and assisted the triangulation of the findings.

Secondary data analysis has also been critiqued for lacking relevant contextual knowledge when the researcher was not involved in the primary research. However, the availability of video and audio files of interviews largely overcomes this problem. Suitability of the data was also assessed through a number of steps before formal analysis commenced: (1) thematic summaries and participant biographies prepared by the primary researchers were read, (2) primary researchers were consulted to gauge the appropriateness of the data for the research purpose, and (3) primary researchers coding books of relevant themes from their initial analyses were made available to the research team. Cognitive interviews also confirmed the relevance of the qualitative findings.

Current studies evaluating ehealth interventions are limited by the lack of a suitable instrument to measure health-related effects associated with using a health website. A person may use guidance, filtering and accreditation tools [29] to help them assess health information on the internet. However, these instruments do not capture how a person may be affected through engaging with a website and users may be concerned of coming across factually correct, yet unwelcome information [30]. Furthermore, such accreditation tools fail to take into account that websites provide more than information, but can also be mechanisms of support. The potential effects of using health-related websites and support groups have been explored [31] using self-report measures which were not specifically developed to capture the range of effects associated with internet use. The development of a generic item pool which will inform a measure to capture the range of effects associated with use of a health-related website is therefore a valuable step toward examining how factual health information and/or experiential information may be best presented online.

4.2. Conclusion

Our analysis suggests that individuals who use the internet in relation to their health may be affected across the five key generic themes: (1) information, (2) feeling supported, (3) relationships with others, (4) experiencing health services, and (5) affecting behavior. These themes are applicable across a range of conditions and are therefore suitable for inclusion in the development of a generic item pool. Items relating to the identified themes have been incorporated into the item pool for the e-Health Impact Questionnaire using words taken from the study population. Items have been tested for acceptability among patients and carers and further tests are being carried out to refine items and establish two independent questionnaires with acceptable psychometric properties. Upon establishing a psychometrically sound instrument it will be possible to compare how particular forms of information (for example factual information compared to experiential information) can affect the internet user.

4.3. Practice implications

This study assists in understanding the effects of using the internet as a source of information and support. This paper documents the first stage of the development of an instrument which will enable standardized comparisons of the effects of using specific websites. Following further psychometric evaluation, the instrument will be suitable for use in clinical trials, observation studies and website evaluation. Research conducted with the proposed instrument will inform recommendations for web developers and health service providers on the best way to present online health information from the users’ perspective.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

Role of funding

The iPEx programme presents independent research funded by the UK National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in England under its Programme Grants for Applied Research funding scheme (RP-PG-0608-10147). The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, representing iPEx, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The funders had no input into the study design; in the collection, analysis and interpretation of data; in the writing of the report; and in the decision to submit the paper for publication.

Acknowledgments

We thank all the participants who took part in the narrative and cognitive interviews. We thank the HERG team, particularly those who carried out the narrative interviews, Angela Martin and the expert reviewers who kindly provided feedback on the draft item pool. We confirm that all patient/personal identifiers have been removed or disguised so the patient/person(s) described are not identifiable and cannot be identified through the details of the story. The views expressed in this paper are those of the authors, representing iPEx, and not necessarily those of the NHS, the NIHR or the Department of Health. The iPEx study group is composed of: University of Oxford (Sue Ziebland, Louise Locock, Andrew Farmer, Crispin Jenkinson, John Powell, Rafael Perera, Ruth Sanders, Angela Martin, Laura Griffith, Susan Kirkpatrick, Nicolas Hughes and Laura Kelly, Braden O’Neill, Ally Naughten), University of Warwick (Fadhila Mazanderani), University of Northumbria (Pamela Briggs, Elizabeth Sillence, Claire Hardy), University of Sussex (Peter Harris), University of Glasgow (Sally Wyke), Department of Health (Robert Gann), Oxfordshire Primary Care Trust (Sula Wiltshire), and User advisor (Margaret Booth).

References

- 1.Department of Health . Stationary Office; London: 2010. Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Department of Health . Stationary Office; London: 2004. Better information, better choices, better health. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Department of Health . Stationary Office; London: 2008. High quality care for all NHS next stage review final report. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dutton W.H., Blank G. Oxford Internet Institute, University of Oxford; 2011. Next generation users: the internet in Britain. Oxford internet survey 2011. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pulman A. A patient centred framework for improving LTC quality of life through Web 2.0 technology. Health Inform J. 2010;16:15–23. doi: 10.1177/1460458209353556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fox S. Peer-to-peer healthcare: many people—especially those living with chronic or rare diseases—use online connections to supplement professional medical advice. Washington: Pew Internet and American Life Project, <http://pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/P2PHealthcare.aspx>; 2011 [cited 20.02.13].

- 7.Streiner D., Norman G. Oxford University Press; Oxford, NY: 2008. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hays R., Revicki D. Reliability and validity (including responsiveness) In: Fayers R., Hays R., editors. Assessing quality of life in clinical trials. Oxford University Press; Oxford, NY: 2005. pp. 25–40. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration . U.S. Food and Drug Administration; Silver Spring, MD: 2009. Guidance for industry: patient-reported outcome measures. Use in medical product development to support labeling claims. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Lohr K.N. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. doi: 10.1023/a:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.European Medicines Agency. Reflection paper on the regulatory guidance for the use of health-related quality of life (HRQL) measures in the evaluation of medicinal products. EMEA/CHMP/EWP139391/2004. London; 2004.

- 12.Bowling A. Open University Press; Berkshire, NY: 2005. Measuring health: a review of quality of life measurement scales. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kerr C., Nixon A., Wild D. Assessing and demonstrating data saturation in qualitative inquiry supporting patient-reported outcomes research. Expert Rev Pharmacoecon Outcomes Res. 2010;10:269–281. doi: 10.1586/erp.10.30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Ziebland S., Wyke S. Health and illness in a connected world: how might seeing and sharing experiences on the internet affect people's health? Milbank Q. 2012;90:219–249. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2012.00662.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Heaton J. SAGE Publications; London/Thousand Oaks/New Delhi: 2004. Reworking qualitative data. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lowe P., Powell J., Griffiths F., Thorogood M., Locock L. “Making it all normal”: the role of the internet in problematic pregnancy. Qual Health Res. 2009;19:1476–1484. doi: 10.1177/1049732309348368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hunt K., France E., Ziebland S., Field K., Wyke S. ‘My brain couldn’t move from planning a birth to planning a funeral’: a qualitative study of parents’ experiences of decisions after ending a pregnancy for fetal abnormality. Int J Nurs Stud. 2009;46:1111–1121. doi: 10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ziebland S., McPherson A. Making sense of qualitative data analysis: an introduction with illustrations from DIPEx (personal experiences of health and illness) Med Educ. 2006;40:405–414. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2929.2006.02467.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NatCen Social Research . NatCen; London: 2012. Framework.http://www.natcen.ac.uk/our-expertise/framework [cited 01.11.12] [Google Scholar]

- 20.McColl E. Developing questionnaires. In: Fayers R., Hays R., editors. Assessing quality of life in clinical trials. Oxford University Press; Oxford, NY: 2005. pp. 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pope C., Ziebland S., Mays N. Analysing qualitative data. Brit Med J. 2000;320:114–116. doi: 10.1136/bmj.320.7227.114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ritchie J., Spencer L. Qualitative data analysis for applied policy research. In: Bryman A., Burgess R.G., editors. Analysing qualitative data. Routledge; London/New York: 1994. pp. 173–194. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sillence E., Briggs P., Harris P.R., Fishwick L. How do patients evaluate and make use of online health information? Soc Sci Med. 2007;64:1853–1862. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2007.01.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Robson C. John Wiley and Sons Ltd.; Oxford: 2002. Real world research: a resource for social scientists and practitioner-researchers. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Willis G., Lessler J.T. Research Triangle Institute; Rockville: 1999. Question appraisal system (QAS-99) [Google Scholar]

- 26.Willis G.B. Sage Publications Inc.; London: 2005. Cognitive interviewing: a tool for improving questionnaire design. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willis G.B. Short course presented at the 1999 meeting of the American Statistical Association. 1999. Cognitive interviewing: a “how to” guide.http://fog.its.uiowa.edu/∼c07b209/interview.pdf [cited 22.02.13] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson M. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates; NJ: 2005. Constructing measures: an item response modeling approach. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Eysenbach G., Powell J., Kuss O., Eun-Ryoung S. Empirical studies assessing the quality of health information for consumers on the world wide web: a systematic review. J Amer Med Assoc. 2002;287:2691–2700. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.20.2691. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chapple A., Evans J., Ziebland S. An alarming prognosis: how people affected by pancreatic cancer use (and avoid) internet information. Policy Internet. 2012;4:3. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Eysenbach G., Powell J., Englesakis M., Rizo C., Stern A. Health related virtual communities and electronic support groups: systematic review of the effects of online peer to peer interactions. Brit Med J. 2004;328:1166. doi: 10.1136/bmj.328.7449.1166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]