Abstract

Background

In an effort to increase effective intervention following opioid overdose, the New York State Department of Health (NYSDOH) has implemented programs where bystanders are given brief education in recognizing the signs of opioid overdose and how to provide intervention, including the use of naloxone. The current study sought to assess the ability of NYSDOH training to increase accurate identification of opioid and non-opioid overdose, and naloxone use among heroin users.

Methods

Eighty-four participants completed a test on overdose knowledge comprised of 16 putative overdose scenarios. Forty-four individuals completed the questionnaire immediately prior to and following standard overdose prevention training. A control group (n =40), who opted out of training, completed the questionnaire just once.

Results

Overdose training significantly increased participants’ ability to accurately identify opioid overdose (p<0.05), and scenarios where naloxone administration was indicated (p<0.05). Training did not alter recognition of non-opioid overdose or non-overdose situations where naloxone should not be administered.

Conclusions

The data indicate that overdose prevention training improves participants’ knowledge of opioid overdose and naloxone use, but naloxone may be administered in some situations where it is not warranted. Training curriculum could be improved by teaching individuals to recognize symptoms of non-opioid drug over-intoxication.

Introduction

Opioid overdose is a significant concern in the New York City (NYC) area. Emergency department (ED) visits related to prescription opioids nearly doubled between 2004 and 2009 (age-adjusted rate from: 55 to 110 per 100,000 New Yorkers) and unintentional poisoning deaths increased by approximately 20%. Although the number of ED visits related to heroin has remained stable during this time frame (152 per 100,000 New Yorkers), opioids in general were the most commonly noted drug in cases of unintentional deaths (NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2011).

These data highlight the need for effective strategies to reduce opioid-related mortality. In an effort to address this concern, programs have been implemented where non-medical persons are given brief education in recognizing the signs of opioid overdose. The curriculum also teaches proper overdose first aid including the use of naloxone, which is provided should they observe an overdose (Doe-Simkins et al., 2009; Hurley et al., 2011).

Naloxone is a short-acting opioid receptor antagonist effective in counteracting the respiratory depression that can lead to death during opioid overdose (White & Irvine, 1999). Although medical professionals have long used naloxone, peer-focused overdose prevention programs have endeavoured to increase access to this life-saving medication. Yet, concerns have been raised regarding this naloxone dispensing practice. Coffin and colleagues (2003) reported that 37% of health care providers indicated that they would not consider prescribing naloxone to patients at risk of heroin overdose. One common concern among prescribers is that drug users would not know how to accurately identify opioid overdoses (Tobin et al., 2005). Researchers have attempted to address this concern. Gaston and colleagues (2009) trained 70 opioid-dependent patients in recognizing and managing opioid overdose. Using pre- and post-training assessments, they found that the number of correct responses significantly increased immediately after training. In another study, 239 treatment-seeking opioid users recruited from 20 sites across England were similarly assessed regarding their knowledge of overdose management and naloxone administration before, and immediately following training (Strang et al., 2008). These investigators found significant improvements in: knowledge of risk factors for overdose, characteristics of overdose, and appropriate overdose management.

Researchers at Yale were the first to develop and validate a tool to quantify knowledge of opioid overdose and naloxone use, the Brief Overdose Recognition and Response Assessment (BORRA; Green et al., 2006). In a subsequent investigation, they found that participants who received a nonstandardized overdose prevention training at one of six U.S. sites recognized more opioid overdose scenarios accurately and instances where naloxone was indicated in comparison to untrained participants (Green et al., 2008). Opioid overdose recognition scores among their trained sample did not significantly differ from medical experts.

The NYSDOH has developed peer-based overdose education programs to distribute naloxone to non-medical personnel, provided they’ve been trained through a registered program. Currently in the U.S. there are no national guidelines for the implementation of these programs. As such, the program specifics, such as the training curriculum, can vary from program to program. Therefore, it is important to perform an evaluation of the knowledge gained from overdose training using a semi-structured overdose education training, such as that mandated by the NYSDOH. The present study sought to combine the methodology used in many of the aforementioned studies in order to perform an assessment of opioid overdose training in NYC, where opioid abuse and overdose is highest in the state (SAMHSA, 2012). The goals were to: obtain a baseline of overdose knowledge among current heroin users who have not received overdose prevention training, observe if training improves that knowledge, and provide the field with approaches to improving the educational value of these programs.

Methods

Recruitment and Inclusion Criteria

Participants were recruited through advertisements in local newspapers, Craigslist.org, and through word-of-mouth. Pre-screening interviews were conducted by research assistants, followed by a more extensive assessment by a research psychologist. Participants were required to be current heroin users between the ages of 21 and 65 years, and able to fluently speak and read English. Potential participants were excluded for active psychopathology that might interfere with their ability to provide informed consent, history of severe learning impairment, or previous basic cardiac life support (BCLS), First-Aid, or overdose prevention training.

Overdose Prevention Training

In total, five training sessions were shadowed in order to gather study data. All trainings occurred between April 2011 and December 2012. Trainings were administered by a single physician’s assistant with the Harm Reduction Coalition (HRC). Although the trainer was aware that a skills assessment would occur, they were not provided with the name of the task, or informed of which aspects of the training it would assess.

Three trainings were conducted in the lobby of the Washington Heights Corner Project, a harm reduction outreach facility. One training was conducted directly in front of Washington Heights Corner Project and another in a meeting room at the HRC office in Midtown Manhattan. Following training, individuals were provided with an overdose response kit that included two separate doses of: intranasal (1 mg/ml) or intramuscular (0.4 mg/ml) formulations of naloxone, a prescription to carry naloxone, and a training certification card. The HRC staff presented a semi-structured lecture designed to address the NYSDOH-required overdose topics: 1) risk factors for opioid overdose, 2) signs of overdose, and 3) how to respond to an overdose. Complete training guidelines can be found online (NYSDOH, 2006).

Assessments

Brief Overdose Recognition & Response Assessment (Green et al., 2006)

The BORRA asks participants to read 16 putative overdose scenarios. Based on the presenting symptoms of the presumed overdose victim, they were asked to decide whether these symptoms were: definitely/probably an opioid overdose, an overdose but NOT an opioid overdose, not an overdose, unsure/not enough info), and if naloxone should, or should not be administered.

Substance Use Inventory (Comer et al., 2008)

This questionnaire was used to determine quantity and frequency of recent drug use and gathered participants’ demographic information, psychiatric history, and experience with drug overdose. Participants were also asked to rate their ability to successfully deliver naloxone on a scale from 0 (not confident) to 10 (completely confident).

Participants

Participants in the trained condition completed the above questionnaires prior to, and following overdose prevention training (50$ compensation was provided). A convenience sample of current heroin users screening at our Substance Use Research Center, opted not to wait until the next training, and chose to complete the BORRA that day and receive 25$. Motivation to complete training and learn more about overdose prevention may vary significantly. As such, the researchers felt that obtaining knowledge of opioid overdose among individuals not interested in training would be an informative comparison.

Statistics

Paired-samples T-tests were utilized to compare pre- and post-training differences in: accurate identification of the signs of opioid overdose, and naloxone indication knowledge quantified using the BORRA. Independent-samples T-tests were used to compare post-training scores against those of untrained opioid users. Respectively, independent-samples T-tests and Pearson χ2 statistic were used to observe for group differences among the continuous and categorical demographic data. Bivariate correlation analyses were also performed in order to examine the relationship between a number of demographic and training variables, and pre-to-post training change in BORRA score.

Results

Overdose Training and Participant Characteristics

Between nine to ten participants were recruited during each training and all overdose prevention presentations were approximately 13–18 minutes in duration. Both trained (N=44) and untrained (N=40) samples consisted primarily of males [χ2 (1) = 1.38, ns] in their early 40’s [t (82) = .88, ns). A roughly equivalent racial/ethnic breakdown was found between trained and untrained groups [χ2 (3) = 2.45, ns]. Participants in the trained group used an average of 5.8 bags of heroin per day, less heroin use than that reported by those in the untrained group [6.8 bags, t (82) = 6.43, p<.05]. Both groups had been using heroin on average for approximately 15 years [t (82) = 2.64, ns]. No significant difference in the number of completed school years was found between the two groups [t (82) = 4.50, ns; Table 1]. There was also no significant difference in the number of overdoses each group had witnessed [t (82) = 0.88, ns].

Table 1.

Participant Demographics and Drug Use

| Trained (n = 44) | Untrained (n = 40) | p | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender, # males (% males) | 37 (84.0%) | 37 (92.5%) | ns |

| Age (SD) | 41.4 (10.0) | 43.2 (8.60) | ns |

| Ethnicity, N (%) | ns | ||

| African-American | 14 (31%) | 15 (37.5%) | |

| Caucasian | 13 (29%) | 12 (30%) | |

| Latino/Hispanic | 14 (31%) | 11 (27.5%) | |

| Mixed/Other | 3 (6%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Bags per Day of Heroin (SD) | 5.8 (0.6) | 6.8 (0.8) | <0.05 |

| Years of Heroin Use (SD) | 15.0 (1.3) | 15.9 (1.8) | ns |

| Daily $ Amount Spent on Heroin (SD) | 55.7 (6.3) | 68.2 (7.6) | <0.05 |

| Route of Heroin Use, N (%) | <0.05 | ||

| Intranasal | 13 (29.5%) | 24 (60%) | |

| Intravenous | 20 (45.5%) | 11 (27.5%) | |

| Multiple Routes | 5 (11%) | 3 (7.5%) | |

| Unreported | 6 (14%) | 2 (5%) | |

| Other Drug Use* | ns | ||

| Tobacco (daily) | 43.0% | 57.5% | |

| Cocaine (daily-weekly) | 43.0% | 25.0% | |

| Alcohol (weekly-monthly) | 34.0% | 32.5% | |

| Marijuana (weekly-monthly) | 27.2% | 15.0% | |

| Prescription Opioids (weekly-monthly) | 25.0% | 10.2% | |

| Benzodiazepines (weekly-monthly) | 9.0% | 7.5% | |

| Years of Education (SD) | 12.5 (0.4) | 11.8 (0.3) | ns |

| Number of Drug Overdoses Witnessed (SD) | 3.1 (0.6) | 3.0 (0.5) | ns |

Participants were asked to rate their use of “other” drugs on a scale using the points of: daily, weekly, or monthly or less. The numbers shown in the table represent the percentage of participants who reported use of each drug within the frequency listed in parenthesis. The anchors in parentheses correspond to the most and least frequently reported use by any individual participant.

BORRA Performance

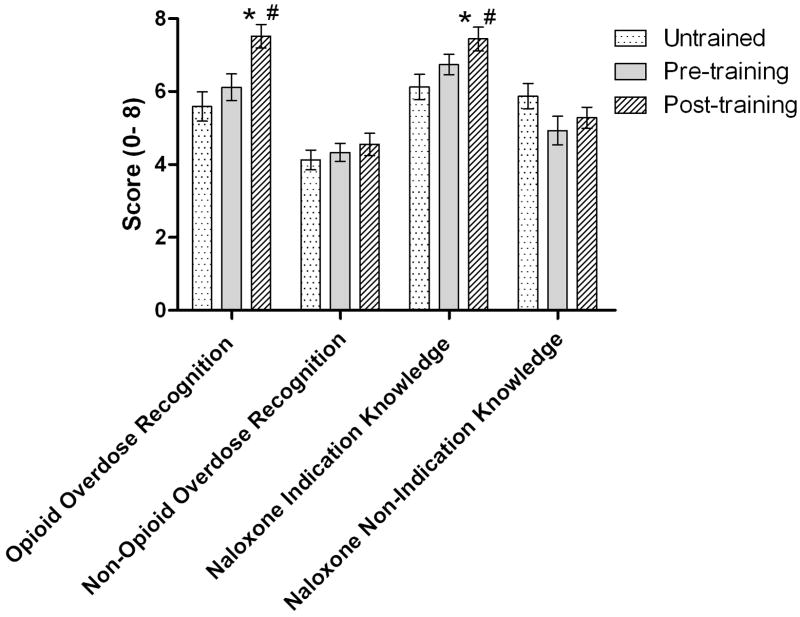

Pre-training BORRA scores did not significantly differ between the trained and untrained groups. When comparing across pre- and post-training BORRA scores in the trained group, significant increases were observed in participants’ ability to accurately identify opioid overdose [t (43) = 18.57, p< 0.05] and scenarios where naloxone administration was indicated [t (43) = 10.72, p< 0.05]. However, training did not alter recognition of non-opioid overdose and situations where naloxone “should not” be administered (Figure 1). When comparing post-training scores against those of the untrained group, scores on measures of accurate opioid overdose identification [t (82) = 20.85, p< 0.05] and correct naloxone administration [t (82) = 17.74, p< 0.05] were significantly higher.

Figure 1.

Mean (± SEM) number of correct responses on BORRA measures of overdose symptom recognition and naloxone indication. # Indicates a significant difference between pre- and post-training scores. * Indicates a significant difference between post-training scores compared against those of untrained controls.

Factors Associated with Change in BORRA Score

Correlation analyses were performed between: “Group Size,” “Training Setting,” “Training Cohort,” and pre- to post-training change in BORRA score (OD knowledge and naloxone knowledge). This analysis allowed us to examine associations between the varying overdose training conditions, and effectiveness of the overdose prevention presentation. No significant correlations were found. In addition, no significant relationships were found between other participant characteristics (age, daily heroin use, years of education and overdose history) and change in BORRA performance.

Effects of Training on Confidence

Prior to training, confidence in naloxone use was similar between the two groups. Prior to training, the trained group rated their confidence at 7.9 (of 10), while the untrained groups rated their confidence at 8.3 [t (82) = 4.20, ns]. After training, confidence in naloxone use was significantly higher (9.4) in comparison to the untrained group [t (82) = 16.17, p< 0.05], and their pre-training baseline [t (43) = 22.09, p< 0.05]. Confidence ratings were not significantly associated with BORRA performance.

Discussion

This study recruited comparable groups of current heroin users in order to investigate the effectiveness of NYSDOH overdose prevention training guidelines. Like other studies, our investigation found that the education provided in the brief training significantly increased participants’ ability to identify opioid overdose, and situations where naloxone administration is warranted (Gaston et al., 2009; Green et al., 2008; Strang et al., 2008). For this investigation, overdose prevention trainings were performed in a number of settings (varying locations, dates, and sizes of the groups trained). Analyses found no correlation between these factors and the effectiveness of the training and no relationship between other demographic variables and pre- and post-training outcomes. These findings imply that the training itself was the only influential factor mediating the improved performance, and that programs may allow significant flexibility in how participants are trained without compromising educational value.

It is important to note that the post-training BORRA performance among this sample is roughly equivalent to that reported in the study conducted by Green et al. (2008). Following training, their sample reported an accurate overdose recognition rate of 85.2% and correct naloxone indication at 84.6%. Accuracy among our sample on these two measures was 75.6% and 79.3%, respectively. Green utilized a more heterogeneous sample, 36% of whom were needle exchange program staff or outreach workers, so their slightly superior performance following training may have been due to: greater learning capabilities, more ambient knowledge of overdose, or better training. Their multi-site design with varying site-specific curricula makes this possibility difficult to explore. In either case, medical experts did not perform significantly better on the BORRA than their trained sample, and performance by our sample was comparable to theirs. These data should help alleviate concerns that drug users cannot accurately identify opioid overdose.

Our data also suggest that the current NYSDOH training curriculum should do more to address recognition of other types of drug overdose. The use of non-opioid drugs is common among our sample of heroin users (Table 1). As such, encounters with non-opioid overdoses are likely. Polydrug use is a cause for concern because it is believed to be a significant risk factor for drug overdose. Ninety-eight percent of all unintentional drug overdose deaths in NYC involved more than one class of drug (NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene, 2011). In particular, the effectiveness of naloxone as a reversal agent for combined opioid and benzodiazepine-induced hypoxia has significant clinical implications. Future studies should also obtain data on overdose reversal outcomes involving longer-acting opioids.

The present study relies heavily on self-report data and is further limited by its small sample of participants who were not randomly assigned to trained and untrained conditions. This study also only employed a single assessment of overdose knowledge among untrained individuals, and would have benefited from a comparator sample of medical experts. Questions still remain regarding this naloxone prescribing practice. Future studies should follow trained individuals in order to observe how training alters interventions employed when encountering an actual overdose, along with possible adverse events related to naloxone administration. Recent research has revealed that drug-using bystanders contact emergency services in less than 30% of suspected overdose situations (Walley, 2013). Research following trained individuals could also address whether an overdose prevention curriculum that highlights the need to alert emergency services actually influences the likelihood that they are notified and subsequent overdose morbidity and mortality. Further investigation should also systematically examine if there are unintentional consequences associated with having naloxone readily available such as changes in opioid and other drug use, and shifts in attitudes about drug abuse treatment.

Important conclusions can be drawn from the present study. Our data argue that the training curriculum used by the NYSDOH significantly increases knowledge related to the identification and management of opioid overdose, and drug users with access to naloxone may constitute a valuable resource in reducing overdose mortality.

Acknowledgments

Funding for this study was provided by National Institute on Drug Abuse grant P50DA09236. Only the authors listed are responsible for the content and preparation of this manuscript. All authors contributed significantly to this work and have read and approved this manuscript for publication. The authors would especially like to thank the clients and staff of the Washington Heights Corner project for their assistance with this project.

Footnotes

Disclosures

The authors declare that over the past three years SDC and JDJ have received compensation (in the form of partial salary support) from investigator-initiated studies supported by Reckitt-Benckiser Pharmaceuticals, Schering-Plough Corporation, Johnson & Johnson Pharmaceutical Research & Development, Endo Pharmaceuticals, and MediciNova. In addition, SDC has served as a consultant to the following companies: Analgesic Solutions, BioDelivery Sciences, Cephalon, Grunenthal, Inflexxion, King, Neuromed, Pfizer, Salix, and Shire. Dr’s Roux, Stancliff and Mr. Matthews have no conflicts to report.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final citable form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Buajordet I, Naess AC, Jacobsen D, Brors O. Adverse events after naloxone treatment of episodes of suspected acute opioid overdose. European Journal of Emergency Medicine. 2004;11:19–23. doi: 10.1097/00063110-200402000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carraro GE, Russi EW, Buechi S, Bloch KE. Does oral alprazolam affect ventilation? A randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. Journal of Psychopharmacology. 2009;23:22–27. doi: 10.1177/0269881108089875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Comer SD, Sullivan MA, Whittington RA, Vosburg SK, Kowalczyk WJ. Abuse liability of prescription opioids compared to heroin in morphine-maintained heroin abusers. Neuropsychopharmacolgy. 2008;33:1179–1191. doi: 10.1038/sj.npp.1301479. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Doe-Simkins M, Walley AY, Epstein A, Moyer P. Saved by the nose: By stander administered intranasal naloxone hydrochloride for opioid overdose. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(5):788–791. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.146647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gaston RL, Best D, Manning V, Day E. Can we prevent drug related deaths by training opioid users to recognize and manage overdoses? Harm Reduction Journal. 2009;6:26–34. doi: 10.1186/1477-7517-6-26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Grau LE, Heimer R. Medical Expert Agreement of Drug User Reported Overdose Symptoms. London: International Harm Reduction Association; 2006. Retrieved 3rd August 2011 from: http://www.ihra.net/uploads/downloads/Conferences/Vancouver2006/Vancouver2006ConferenceAbstractBook.pdf. [Google Scholar]

- Green TC, Heimer R, Grau LE. Distinguishing signs of opioid overdose and indication for naloxone: an evaluation of six overdose training and naloxone distribution programs in the United States. Addiction. 2008;103(6):979–989. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02182.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hurley R. Pilot scheme shows that giving naloxone to families of drug users would save lives. British Medical Journal. 2011;343:d5445. doi: 10.1136/bmj.d5445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim D, Irwin KS, Khoshnood K. Expanded access to naloxone: options for critical response to the epidemic of opioid overdose mortality. American Journal of Public Health. 2009;99(3):402–407. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2008.136937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- New York City Department of Health. Guidelines for Training Providers. 2006 Retrived November, 2011 from: http://www.health.ny.gov/diseases/aids/harm_reduction/opioidprevention/programs/guidelines/docs/training_repsonders.pdf.

- New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Drugs in New York City: Misuse, morbidity and mortality update. 2011 Retrieved 15th June, 2012 from: http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/epi/epi-data-brief.pdf.

- Strang J, Manning V, Mayet S, Best D, Titherington E, Santana L, Offor E, Semmler C. Overdose training and take home naloxone for opiate users: Prospective cohort study of impact on knowledge and attitudes and subsequent management of overdoses. Addiction. 2008;103(10):1648–1657. doi: 10.1111/j.1360-0443.2008.02314.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration. HHS Publication No (SMA) 12-4699, DAWN Series D-36. Rockville, MD: 2012. Drug Abuse Warning Network, 2010: Area Profiles of Drug-Related Mortality. [Google Scholar]

- Tobin KE, Gaasch WR, Clarke C, MacKenzie E, Latkin CA. Attitudes of emergency medical service providers toward naloxone distribution programs. Journal of Urban Health. 2005;82(2):296–302. doi: 10.1093/jurban/jti052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walley AY, Xuan Z, Hackman HH, Quinn E, Doe-Simkins M, Sorensen-Alawad A, Ruiz S, Ozonoff A. Opioid overdose rates and implementation of overdose education and nasal naloxone distribution in Massachusetts: interrupted time series analysis. BMJ. 2013 doi: 10.1136/bmj.f174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White JM, Irvine RJ. Mechanisms of fatal opioid overdose. Addiction. 1999;94:961–972. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]