Abstract

Although numerous studies have evaluated the effectiveness of multi-modal psychosocial interventions for children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, these programs are limited in that there has not beeti an explicit focus on the connection between fatnily and school. This study was designed to develop and pilot test a family-school ititervention, Family-School Success—Early Elementary (FSS-EE), for kindergarten and first-grade studetits with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. Key components of FSS-EE were family-school behavioral consultatioti, daily report cards, and strategies to improve parent-child relationships atid family involvement in educatioti. FSS-EE was developed using a multistep iterative process. The piloted version consisted of 12 weekly sessions including 6 group meetings, 4 individualized family sessions, and 2 school-based consultations. Families participating in the study were given the choice of placing their childreti on medication; 25% of children were on medication at the time of random assignmetit. Childreti (n = 61) were randomly assigned to FSS-EE or a comparison group controlling for nonspecific treatment effects. Outcomes were assessed at post interventioti and 2-month follow-up. Study findings indicated that FSS-EE was feasible to implement and acceptable to paretits atid teachers. In addition, the findings provided preliminary evidence that FSS-EE is effective in improving parenting practices, child behavior at school, and the student-teacher relationship.

Success in early elementary school is critical for healthy child development. Developmental research has indicated that early school success is highly dependent on the quality of the home environment (Christenson & Sheridan, 2001; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, 2005). A fatnily environment in which there is a strong parent–child attachment promotes child self-regulation and prepares the child to become engaged in academic work and relate effectively with teachers and peers upon entering school. In turn, successful teacher–student relationships contribute to strong academic achievement and effective peer interactions (Graziano, Reavis, Keane, & Calkins, 2007; Pianta, 1997). Further, parental involvement in education, including supporting educational activities at home and collaborating with teachers, has been shown to promote child success in the school (Christenson & Reschly, 2009).

The emergence of attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) early in schooling clearly introduces a set of risk factors to the developing child. Cross-sectional and longitudinal studies have demonstrated that young children with ADHD present with functional impairments that are similar to those of older children with this disorder. For example, preschool children with ADHD are more impaired than same-aged peers without ADHD in multiple domains (e.g., behavior, acadefnic skills, social skills) and multiple settings (Greenhill, Posner, Vaughan, & Kratochvil, 2008; Spira & Fischel, 2005), and these impairments continue throughout childhood and into adolescence (Lahey et al, 2004; Lee, Lahey, Owens, & Hinshaw, 2008). Moreover, a number of studies have demonstrated that young children with ADHD experience deficits in early language development, literacy, and numeracy skills as compared to same-age children without ADHD (DuPaul, McGoey, Eckert, & VanBrakle, 2001; Spira & Fischel, 2005). These deficits are particularly noteworthy because of the strong relationship between emerging academic skills and later academic achievement (Ferriero & Teberosky, 1982). Finally, in addition to academic and behavioral deficits, young children with ADHD have been found to have significant relationship problems with adults and peers across settings (Egger, Kondo, & Angold, 2006; Graziano et al, 2007).

Research has demonstrated that psychosocial interventions, such as behavioral parent training and teacher consultation, for young children with ADHD can have positive effects on children's behavioral functioning and academic performance. Some of the positive effects include decreased child behavior problems at home and school, improved academic productivity and homework performance, decreased parental stress, and increased parenting skill (Fabiano et al, 2009; Langberg et al, 2010; Owens, Storer, & Girio-Herrera; 2011; Williford & Shelton, 2011).

Although parent training and teacher consultation programs have beneficial effects for children with ADHD, these approaches often target only one system (i.e., home or school) at a time. Parent training programs can have an effect on school performance (Corcoran & Dattalo, 2006), but the effectiveness of this parent-mediated approach with regard to improving school outcomes is limited. Similarly, most school interventions focus little attention on child functioning at home, and the effect of classroom interventions on parent–child relationships and child behavior at home is often not assessed (Lahey et al, 2007).

Since the early 1990s, numerous intervention programs for children with ADHD have been developed that include components focused on both the school and family. For example, the Multimodal Treatment Study of ADHD (MTA) included parent training, teacher consultation, classroom support from a paraprofessional, and behavioral interventions in a summer camp (Wells et al., 2000). In addition, several other investigative teams have developed and evaluated programs involving classroom interventions and parent training (e.g., Abikoff et al., 2004; Kern et al., 2007; Owens, Murphy, Richerson, Girio, & Himawan, 2008; Pfiffner, Mikami, Huang-Pollock, Easterlin, Zalecki, & MvBurnett, 2007).

Although these multimodal programs represent a substantial improvement over prior intervention attempts, their effects may be limited because of a failure to explicitly target the connection between home and school, parent involvement in education, or improving the parent–teacher relationship. A substantial body of evidence has demonstrated that family involvement in education is associated with greater student competence (Christenson & Reschly, 2009); however, families of children with ADHD often feel ineffective in supporting their children's education (Rogers, Wiener, Marton, & Tannock, 2009). Structuring the home environment so that it promotes their children's education may be difficult for these families, because of conflicted parent–child relationships and noncompliant child behavior. Moreover, parents of children with ADHD generally feel less welcome in school compared to the parents of children without ADHD (Rogers et al., 2009), and conflict between the family and school is common among students with ADHD (Mautone, Lefler, & Power, 2011). Therefore, it is important that intervention programs for children with ADHD encompass a focus on family involvement in education, including the family–school relationship.

Study Aims and Hypotheses

The purpose of this article is to describe the development and findings of a pilot test of a family–school intervention program (Family-School Success—Early Elementary [FSS-EE]) for young children with ADHD, a program uniquely designed to strengthen family involvement in education and the family–school relationship, in addition to improving parenting practices. The program included a focus on teaching strategies to encourage family involvement in education at home. In addition, the Conjoint Behavioral Consultation (CBC; Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2008) model was used as a framework for supporting the development of collaborative family–school relationships. In the context of a family–school partnership, daily report cards were developed and implemented by parents and teachers.

The study was designed to examine intervention acceptability and explore potential effectiveness in relation to a comparison intervention designed to control for the nonspecific effects of treatment. The study examined FSS-EE in relation to the comparison intervention with regard to (a) participants’ views about treatment acceptability, and (b) improvements in family involvement in education, parenting practices, child functioning in the family, and student functioning in school.

Method

Participants

This study was conducted through an ADHD center within a pédiatrie hospital located in a large metropolitan area in the northeast section of the United States. Inclusion criteria were the following; (a) children enrolled in kindergarten or Grade 1 ; (b) children meeting criteria for any ADHD subtype based upon parent report on the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School Age Children (K-SADS-P IVR; Ambrosini, 2000); (c) children rated at or above the 90th percentile on the Inattention or Hyperactivity-Impulsivity factor of the ADHD Rating Scale—IV School Version (DuPaul, Power, Anastopoulos, & Reid, 1998), or the Attention Problems or Hyperactivity subscales of the Behavior Assessment System for Children, Second Edition—Teacher Rating Scales (Reynolds & Kamphaus, 2004); and (d) children scoring at or above an estimated IQ of 75 on the two-subtest version of the Wechsler Abbreviated Scale of Intelligence (Wechsler, 1999).

Children with leaming disabilities, disruptive behavior disorders, and internalizing disorders generally were included. Children meeting Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (fourth edition; DSM-IV) criteria based on parent report on the K-SADS-P IVR for a psychotic disorder, chronic tic disorder or Tourette's disorder, anxiety or mood disorder serious enough to warrant separate treatment, history of major neurological illness, and history of suicidal or homicidal behavior or ideation were excluded. Children who were prescribed medication to treat symptoms of ADHD were included (see Medication Monitoring section later for details).

Potential subjects for the study were identified in two ways: (a) parent-initiated referrals from the hospital's ADHD center, which were screened for eligibility; and (b) referrals from school and community providers. Children were referred because of concems regarding inattention and/or hyperactivity, especially in school. Potentially eligible families were contacted by telephone by a research assistant (RA) to determine the child's grade level and the parent's preference for medication use during the study. If the child met initial inclusion criteria based on this screening, the RA requested that tiie parent obtain teacher rating scales. The RA then determined whether the child met the screening criterion for teacher ratings. If the child was taking medication at the time of screening and ratings were below the 90th percentile, scores from previous evaluations, prior to the start of medication treatment, were reviewed. If screening ratings met eligibility criteria, the family was contacted, and a clinic visit was scheduled to conduct the diagnostic evaluation. Diagnostic interviews were audio recorded and 20% were selected at random for review by an independent clinician/doctoral trainee. Inter-rater agreement was 93.3% (κ = 0.86) for ADHD, Combined Type; 100% (κ = 1.00) for ADHD, Inattentive Type; and 93.3% (κ = 0.82) for ADHD, Hyperactive/Impulsive Type.

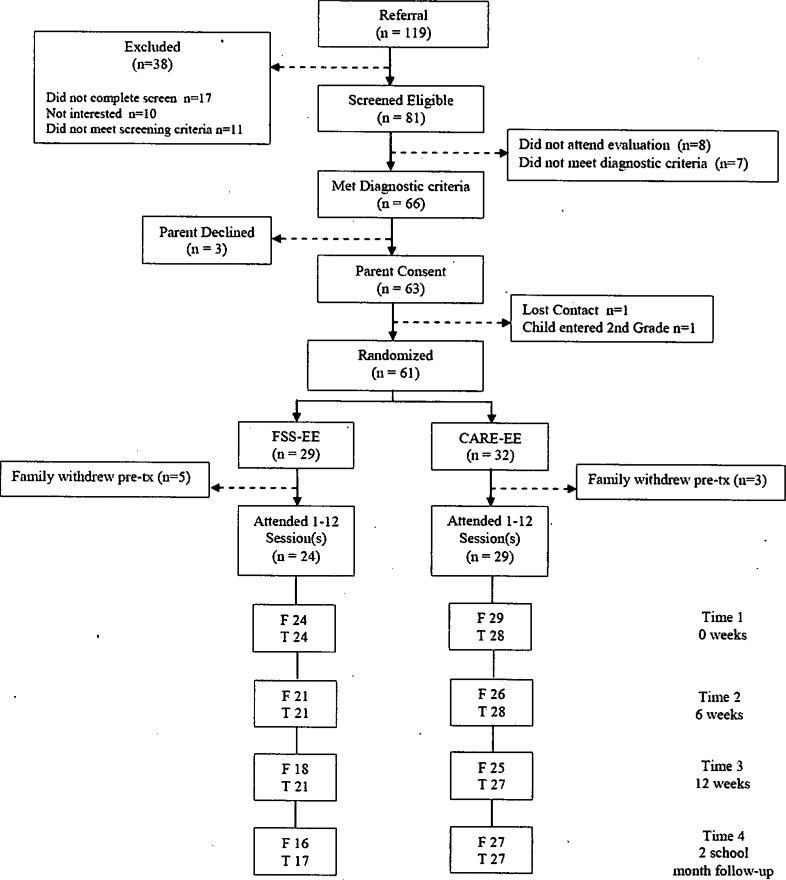

Figure 1 illustrates the flow of participants though the recruitment and random assignment process. Parent consent was obtained for 63 families. Of the consented families, 61 were randomly assigned to a treatment group (the study team lost contact with one family and in another case the child entered second grade prior to enrolling in the psychosocial intervention). Before the start of intervention, five families withdrew from the FSS-EE group, and three withdrew from the comparison group, for a total of 53 participants (i.e., 24 in FSS-EE and 29 in the comparison intervention). Groups were stratified by child medication status, presence of a co-morbid internalizing disorder, and presence of an externalizing disorder.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of participation from screening to the 2-month follow-up assessment. FSS-EE = Family-School Success—Early Elementary; CARE = Coping with ADHD through Relationships and Education; F = families completing measures; T = teachers completing measures.

Intervention Development

During the initial 6-month phase of the study (prior to the pilot study involving the 53 families just described), the research team was invested in an iterative process of intervention design, resulting in development, modification, and refinement of the treatment manual. Sources of information for intervention development included the following; (a) a review of the relevant literature; (b) consultation with experts in family–school collaboration, early elementary education, and interventions for children with ADHD; (c) focus groups with parents and teachers of young children with ADHD; and (d) an initial try-out of the intervention program with a small cohort (n = 3) of families. Throughout the initial try-out, the intervention team conducted interviews with participants, and their feedback was used to modify the intervention manual.

The resulting program, FSS-EE, is a 12-session family–school intervention designed to improve parent–child relationships, parenting skills, family involvement in education, and family–school collaborative problem solving. In addition to standard parent training components, FSS-EE incorporates elements of CBC (Sheridan & Kratochwill, 2008) as well as daily report cards (DRCs) and strategies for increasing family involvement in education at home (e.g., shared reading and reduction in screen time).

FSS-EE provides intervention using three formats: (a) parent group meetings (6 sessions) held simultaneously with separate child group sessions; (b) individualized family therapy (4 sessions; 3 include parents and child; 1 for parents only); and (c) family–school consultations (2 sessions) held at the school. Child group sessions are recreational and introduce the children to the strategies being taught to their parents (see Power, Karustis, & Habboushe, 2001). A token economy program is used during the child group sessions. An outline of program sessions is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Description of each session for Family School Success. – Early Elementary

| Session Title | Session Type | Session Content |

|---|---|---|

| 1 – Introduction to Family School Success – Early Elementary | Group | Introduction to FSS-EE – review “big ideas” |

| Importance of family involvement in education | ||

| Using attention to change child behavior | ||

| 2 – Building the parent-child relationship | Individual Family | Review positive attending |

| Introduction to The Child's Game (child-directed play) | ||

| 3 – Preparing for home-school collaboration | Individual Family | Review The Child's Game |

| Rationale for CBC and DRC (identify DRC goals) | ||

| Discuss building partnerships with teachers | ||

| 4 – Promoting home-school collaboration | School Meeting | Establish collaborative home-school relationship |

| Establish use of assignment book & DRC | ||

| Teacher support of home-based educational activities | ||

| 5 – Basics of behavior management | Group | Group discussion of school meetings |

| Functional assessment of problem behaviors (antecedents and consequences) | ||

| 6 – Token economy and home learning environment | Group | Establishing a token economy |

| Family involvement in education: home-based activities | ||

| 7 – Developing home-based learning activities | Individual Family | Review of strategies to date – problem-solving barriers to implementation |

| Informal learning opportunities – “natural teaching moments” | ||

| 8 – Home-based learning activities | Group | The Child's Educational Game |

| Parent tutoring to enhance learning | ||

| 9 – Using punishment successfully | Group | Rationale for using punishment strategically |

| Response cost and time-out | ||

| Prepare for second school consultation | ||

| 10 – Collaborating to Refine Strategies | School Meeting | Review use of DRC and modify if needed |

| Additional strategies for home-based learning | ||

| 11 – Strengthening the caregiver partnership | Individual family (parents only) | Review strategies to date and problem-solve barriers |

| Strengthening the parenting alliance | ||

| 12 – Integrating skills and planning for the future | Group | Review and problem solve implementation difficulties |

| Develop individual family “Formulas for Success” | ||

| End of program celebration |

Note: CBC = Conjoint Behavioral Consultation; DRC = Daily Report Card

The pilot study began after the 6-month period of intervention development and refinement. During the pilot study, one clinician was assigned to work with each cohort of parents assigned to the FSS-EE intervention. This clinician conducted parent group sessions and had responsibility for working with families in individualized family sessions and school-based sessions. In addition, four clinical assistants (graduate students in applied psychology) worked with each child group to ensure that children's behavior was managed appropriately and safely. Sessions were held on a weekly basis. The initial session lasted 3 hr. Subsequent group sessions were 90 min in length. Individualized family sessions lasted 60 min, and school sessions were approximately 45 min. Two brief phone conferences between the clinician and the teacher were conducted after Sessions 6 and 8 to monitor the child's progress and modify the DRC, if necessary.

Several procedures were used to elicit teacher investment at the outset: (a) a letter briefiy explaining the study was sent to teachers and their principals after the family provided consent; (b) a phone call to the teacher was initiated by the clinician to introduce the study and schedule time for a meeting; (c) the clinician visited the school to obtain authorization from the principal for the teacher to participate, obtain teacher consent, and provide the teacher with an explanation of the treatment being offered. Additional goals for this meeting were for the clinician to establish rapport with the teacher and identify the teacher's primary concerns about the child.

Five FSS-EE cohorts were conducted. The number of families per group ranged from 2 to 6 (mean = 4.8). Three clinicians (i.e., postdoctoral fellows in school or clinical child psychology) conducted the groups: two conducted two groups each with a total of 8 and 11 families, respectively; a third conducted a group with 5 families. Twenty-four teachers participated in the intervention; 2 of these teachers were also involved in the comparison treatment for one child each in different cohorts (i.e., the teachers did not participate in FSS-EE and the comparison treatment at the same time).

Comparison Intervention

The comparison intervention was Coping with ADHD through Relationships and Education (CARE), which is a 12-session parent support and education program developed in a previous study (Power et al, 2012) to control for the nonspecific effects of intervention. CARE includes three components: (a) discussing children's progress, (b) establishing a context within which parents can support each other, and (c) providing generic education to parents about ADHD. The content of CARE sessions did not address the primary components of FSS-EE. Parents were provided education about ADHD (e.g., information about core behaviors, impairments, causes, and developmental course of ADHD); they were not provided training in the use of empirically supported interventions. CARE did not involve parents and teachers in the process of problem solving (i.e., did not use the CBC model or DRCs), nor did it involve training parents in the use of contingency management strategies or strategies to support family involvement in education. During CARE, children met in groups concurrent with parent group sessions. Children in CARE received education on topics covered in the parent groups and engaged in fun, recreational activities. Similar to FSS-EE, the child group clinicians used a token economy to support behavioral management. One clinician was assigned to work with each cohort of parents, and four clinical assistants (graduate students in applied psychology) worked with each child group.

CARE included 11 group sessions and 1 family–school meeting. Sessions were held on consecutive weeks. The initial session was 3 hr in duration and subsequent meetings were 75 min (approximately the average amount of time spent with families in FSS-EE sessions). The purpose of the school meeting was to acquire information about school functioning and not to engage in behavioral consultation. The same procedures were used to obtain teacher consent and investment as were described for FSS-EE.

Five CARE cohorts were conducted. The number of families per group ranged from 4 to 8 (mean = 5.8). Four clinicians (i.e., two postdoctoral fellows in school or clinical child psychology and two licensed psychologists) conducted CARE groups; the clinicians providing CARE were not the same as those offering FSS-EE. One CARE clinician conducted two groups with a total of 12 families; three conducted one group each (4, 5, and 8 families, respectively). Thirty teachers participated in the intervention. Two teachers were involved in CARE for two children each; two children participated in the same cohort, and two were in separate cohorts.

Intervention Procedures

Program manuals were developed for both FSS-EE and CARE. All clinical activities for both programs were supervised by a school psychologist who was a licensed provider. Before the start of each cohort, the FSS-EE and CARE clinical teams reviewed the program manuals and met with the clinical supervisor for 2 hr of program-specific training. In addition, the clinical assistants received approximately 2 hr of training related to child behavior management and implementation of a token economy. Throughout intervention implementation, parent group leaders met with the supervisor weekly for 1 hr of individual supervision. Before each group session, clinical assistants met with the parent group leader for group supervision. To prevent contamination, clinicians for CARE received explicit, weekly instructions from their supervisor not to (a) engage in problem-solving activities with parents, (b) discuss contingency management approaches, or (c) suggest strategies for building the family–school relationship. The supervisor directly observed approximately 50% of the FSS-EE and CARE sessions to ensure adherence and treatment differentiation, and all clinicians were blind to study hypotheses.

Content Integrity and Participant Engagement

All group and individual family sessions were videotaped, and school sessions were observed live or audio taped to evaluate content integrity. Video, audio, and live observations were conducted by independent observers trained in each program's manual. Integrity checklists detailing all content to be delivered during each FSS-EE and CARE session were used by the observers to evaluate the extent to which each component of the intervention was implemented (i.e., 0 = not implemented, 1 = partially implemented, 2 = fully implemented). In addition, CARE checklists included four “do not” items to ensure that CARE clinicians did not implement the primary components of FSS-EE (i.e., problem solving, discussion of contingency management, discussion of strategies to build family–school relationships, and discussion of strategies to build parent–child relationships).

Integrity levels were high for both FSS-EE and CARE. For FSS-EE, integrity checks were conducted on 29% of individual, 33% of group, and 13% of school sessions. For FSS-EE individual sessions, on average 94% of intervention components were fully implemented. For group sessions, clinicians fully implemented 80% of the intervention components. Finally, for school sessions, clinicians fully implemented 86% of the intervention components. For CARE, integrity checks were conducted on 25% of group and 14% of school sessions. For CARE group sessions, on average clinicians fully implemented 90% of the intervention components and only 8% of the “do not” components, and for school sessions 100% of the content was fully implemented, and 6% of the “do not” components were implemented. These data indicate clear differentiation between the FSS-EE and CARE interventions.

To assess participant engagement, another component of treatment integrity (Sanetti & Kratochwill, 2009), family attendance at sessions and adherence to recommended intervention strategies were monitored. Clinicians kept records of family attendance at FSS-EE and CARE sessions, and FSS-EE clinicians collected permanent products (i.e., completed worksheets) at each session to monitor parental adherence. Permanent products were coded by trained research assistants for completion.

Average attendance for regularly scheduled sessions was 9.5 (SD = 3.3) for the families who participated in FSS-EE clinicians (N = 24), and 75% of families attended at least 9 of the 12 sessions. Families who participated in CARE (N = 29) attended an average of 10.1 (SD = 2.6) regularly scheduled sessions; 79% of participants attended at least 9 of 12 sessions. Although attendance was relatively high, parent adherence with between session homework assignments in FSS-EE was variable; of the eight assignments given, 31%–76% were partially or fully completed. No homework was assigned for CARE.

Medication Monitoring

Families were given the option to enroll in the study with or without medication. If families elected to have their child take medication, they were instructed to work with a community provider to identify the most effective medication and dose prior to enrolling in the intervention. Once the family reported that the child had been stable on a medication and dose for at least 2 weeks, the family was assigned to a treatment group, and subsequentiy baseline data were collected. Parents were asked to provide information about child medication status at each intervention session and during follow-up data collection.

Fifteen children (25%) were prescribed long-acting stimulants (10 children received methylphenidate compounds and 5 received amphetamine compounds) to treat ADHD at the time baseline data were collected (FSS-EE = 9 [31%]; CARE = 6 [19%]). Medication remained relatively stable throughout the study; only 4 (8%) children across both treatment arms demonstrated a change in medication status between baseline and postintervention involving a shift from off to on medication or a change from one stimulant to another. Two children (1 from each arm) began taking a stimulant, and 2 other children (1 from each arm) switched stimulants.

Outcome Measures

Measures of intervention acceptability

The Treatment Evaluation Inventory, Short Form (TEI-SF; Kelley, Heffer, Gresham, & Elliott, 1989), a 9-item measure, was used to evaluate treatment acceptability from parents’ perspectives. The alpha coefficient for the TEI-SF in this study was .75. The Intervention Rating Profile—10 Item Version (IRP-10; Power, Hess, & Bennett, 1995) was used to examine teacher perceptions of intervention acceptability, and the alpha coefficient in the present sample was .96.

Measures of family involvement in education

The 13-item Family Involvement Questionnaire (FIQ) Home-based Involvement factor was used to assess caregiver engagement in educational activities and parenting practices to support their child's leaming (Fantuzzo, Tighe, & Childs, 2000). Parents self-report the frequency of their behavior using a 4-point scale. In the current sample, the Cronbach's alpha coefficient for this factor was .86. Also, a 10-item version of the Parent as Educator Scale (PES; Hoover-Dempsey, Bassler, & Brissie, 1992) was used to assess the extent to which caregivers perceive themselves as effective in assisting with their child's education. Each item is rated on a 5-point scale. In this study, the alpha coefficient was .85. Finally, the Parent-Teacher Involvement Questionnaire (PTIQ; Kohl, Lengua, McMahon, & Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group, 2000) was used to assess the quality of the family–school relationship. A factor analysis of this measure uncovered an 11-item Quality of Parent–Teacher Relationship factor consisting of parent- and teacher-reported items. As in previous studies, parent and teacher reports on items pertaining to this factor were aggregated into a composite score (alpha coefficient in the present sample was .89).

Measures of parenting practices

The Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire (PCRQ; Furman & Giberson, 1995) was used to assess parent perceptions of the quality of the parent-child relationship. In the present study, the Negative/Ineffective Discipline factor was used, and the alpha coefficient for this factor was .84.

In addition, the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (3rd ed.; DPICS; Eyberg, Nelson, Duke, & Boggs, 2004) was used to assess parenting practices. Frequencies of parent and child behaviors were continuously coded during two standardized situations (i.e., child-led play and parent-led cleanup tasks). For this study, we used two composite categories for parents’ behavior that have demonstrated treatment sensitivity in previous studies of young children with externalizing problems (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007; Lyon & Budd, 2010). The “Do Skills” composite (behavior descriptions, reflections, and praises) assesses effective parenting strategies, and the “Don't Skills” composite (questions, commands, and negative talk) captures strategies that are ineffective for managing child behavior. These two composites were used in both child-led play and cleanup situations with one modification (i.e., the Direct Commands category was removed from Don't Skills for the cleanup task because parents would be expected to give direct commands during this situation).

Each DPICS session was videotaped. Videotapes were given IDs created by a random number generator. This ensured that coders were unable to identify intervention condition and data collection period when coding. Coders were RAs trained in accordance with the DPICS manual (Eyberg et al., 2004). A study investigator coordinated training, which consisted of studying the manual, meeting to review behavioral categories, and partnering with the lead trainer to practice and review difficult examples. Coders were required to reach 80% agreement with a standard criterion video before coding participant videos. The study investigator continued reliability checks and booster trainings to minimize observer drift. To evaluate inter-rater reliability, the investigator conducted checks on 36 (20.2%) of the play and cleanup sessions. Frequency counts for each composite were obtained by each rater. Disagreements between raters were identified as the difference between frequency counts. Percent agreement was calculated as the sum of agreements divided by agreements plus disagreements across participants and assessment points (see Bagner & Eyberg, 2007). For the play sessions, percent agreement was 90.3% for Do Skills and 96.0% for Don't Skills. For the cleanup sessions, percent agreement was 92.0% for Do Skills and 92.6% for Don't Skills.

Measures of child functioning in the family

The MTA Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham questionnaire—IV (SNAP-IV; Swanson et al., 2001), completed by parents, was used to assess ADHD and ODD symptoms manifesting at home. The 26 items of the SNAP-IV correspond to the symptom descriptions for ADHD and ODD outlined in the DSM-IV. To obtain a composite index of child behavior, the mean item score from ADHD and ODD combined was used in analyses. The alpha coefficient in the present sample for parent ratings was .91. In addition, child compliance (i.e., responsiveness to parent commands) during the cleanup task on the DPICS was used as a direct observation measure of child functioning in the family. Inter-rater reliability for compliance was 85.8%.

Measures of child functioning in school

The Academic Competence Evaluation Scales (DiPerna & Elliott, 2000) is a teacher-report scale that assesses academic competence. The Academic Enablers (e.g., academic engagement, motivation) composite was used in this study. Teachers rate the frequency of each item on a 5-point Likert scale. Strong reliability and validity have been extensively documented (e.g., DiPerna, Volpe, & Elliott, 2002). The 15-item Student-Teacher Relationship Scale—Short Form (Pianta, 2002) evaluates the teacher's perception of quality of the student– teacher relationship. Two factors compose the measure—Closeness (i.e., warmth of interactions) and Confiict (i.e., discord in the relationship)—and items are rated on a 5-point Likert scale. For this study, the total mean item score was used, and the alpha coefficient was .78. The MTA SNAP-IV (Swanson et al., 2001), completed by teachers, was used to assess ADHD and ODD symptoms manifesting at school. The coefficient alpha in the present sample was .93.

Assessment procedures

Data were collected at baseline, midpoint, post-treatment, and 2-month follow-up. Data collectors were blind to study hypotheses. Parent- and teacher-report measures and videotaped parent–child interactions were collected prior to the first intervention session, between Sessions 6 and 7, after Session 12, and 2 school months (i.e., summer months were not counted) after Session 12. Teachers received the measures in the mail approximately 1 week prior to the scheduled data collection period. Parents and teachers received a $20 cash stipend for completing measures at each period.

Statistical Analyses

A linear mixed-effects regression model was used to analyze outcomes at postintervention and follow-up. The analyses were based on an intent-to-treat approach. The SAS Proc Mixed procedure was used with the following general linear model: Y = Treatment Group + Medication Status + Time + Treatment Group × Medication Status + Treatment Group × Time + Medication Status × Time + Treatment Group × Medication Status × Time. In this model, Y = score on outcome measure; Treatment Group = FSS-EE or CARE; Medication Status = on or off medication at baseline; and Time = the four assessment points. In these models, only intercepts were defined as a random effect. The aims were examined separately for effects at postintervention and follow-up. The Treatment Group × Time interaction effect indicated whether there was a significant effect of intervention over time. However, the three-way interaction of Group × Time × Medication Status was examined to determine whether the effect of intervention varied as a function of medication status. Prior to conducting statistical testing, each outcome measure was carefully examined to identify outliers and to determine whether the assumptions needed for parametric testing were met. For several outcome measures (i.e., FIQ, DPICS “Do” Skills for child-led play and cleanup, and DPICS “Don't” Skills for cleanup), scores for the FSS-EE and CARE groups were significantly different at baseline. These analyses were conducted with adjustments for baseline group differences. SAS software version 9.2 and SPSS software version 19 were used to conduct the analyses. Because this was an exploratory study, each outcome measure was evaluated at p<.05. Effect sizes (ESs) were estimated by calculating the difference in change scores for each group (FSS vs. CARE) between postintervention (follow-up) and baseline and dividing this by the standard deviation (SD) of the change scores for the FSS-EE group. In estimating ES, we used the treatment group SD as the denominator instead of the pooled SD, because our findings suggested that the pooled SD generally would have underestimated the error term (i.e., the SD for the FSS-EE group was larger than that of the CARE group on 9 out of 13 outcome measures, and in most of these cases the difference was substantial).

Results

Characteristics of Participants

The groups (FSS-EE and CARE) were compared to determine whether there were differences as a function of demographic variables, ADHD subtype status, and presence of comorbid conditions (see Table 2). The groups did not differ on any of these factors. Collapsing across groups, 40% of the children were in kindergarten, and the other 60% were in first grade. Twenty-eight percent of the participants were female, and 95% of families were classified as belonging to the three highest categories of the Hollingshead (1975) scale, reflecting that the sample consisted primarily of families in the middle and upper middle socioeconomic groups. With regard to ethnicity, 88% were non-Hispanic and 12% were Hispanic; with regard to racial composition, 75% were White, 21% were Black/African American, and 3% were multiracial. Regarding ADHD, 59% had Combined Type, 28% had Hyperactive-Impulsive Type, and 13% had Inattentive Type. Altogether, 25% of participants were taking medication at baseline.

Table 2.

Baseline Demographic and Diagnostic Characteristics for Family-School Success-Early Elementary (FSS-EE; n=29) and Coping with ADHD through Relationships and Education (CARE; n=32)

| FSS-EE | CARE | Difference | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (% female) | 31.0 | 25.0 | p = .776 |

| Grade level (% kindergarten) | 27.6 | 50.0 | p = .115 |

| Single parent status (%) | 24.1 | 15.6 | p = .523 |

| Hispanic (%) | 13.8 | 9.4 | p = .669 |

| Non-Hispanic (%) | 86.2 | 90.6 | – |

| African American (AA) (%) | 24.1 | 18.8 | p = .870 |

| White (%) | 72.4 | 78.1 | – |

| Multiracial (%) | 3.4 | 3.1 | – |

| SES (% Levels III, IV, V on Hollingshead) | 93.1 | 96.9 | p = .600 |

| ADHD, Combined (%) | 62.1 | 56.3 | p = .814 |

| ADHD, Inattentive (%) | 10.3 | 15.6 | – |

| ADHD, Hyperactive-Impulsive (%) | 27.6 | 28.1 | – |

| ODD (% with disorder) | 34.5 | 25.0 | p = .575 |

| Anxiety or Mood Disorder (% with disorder)* | 0.0 | 0.0 | p = 1.00 |

| Medication status at Baseline (% on medication) | 31.0 | 18.8 | p = .374 |

Note: SES refers to socioeconomic status, as assessed by the Hollingshead (1975) index of social status. Levels III, IV, and V reflect the middle to high levels of the scale. ODD = Oppositional Defiant Disorder

Children with specific phobias and no other anxiety or mood disorder were excluded.

Treatment Acceptability

Parent ratings of acceptability were obtained for 75% and 86% of families enrolled in FSS-EE and CARE, respectively (i.e., ratings were obtained for participants who remained in the intervention and returned for post-treatment data collection). On the parent-rated TEI, mean item scores for FSS-EE at post-treatment (M = 3.34; SD = 0.41) were significantly higher than scores for CARE [M = 3.03; SD = 0.40; t(41) = 2.52, p = .016; ES = 0.78]. Given that mean item scores on the TEI can range from 0 to 4, ratings for both groups refiected high levels of acceptability. On the teacher-rated IRP-10 (completed by 88% of teachers in FSS-EE and 93% of teachers in CARE), mean item scores for FSS-EE at post-treatment (M = 5,07; SD = 0.72) were similar and not significantly different from scores for CARE (M = 4.73; SD = 0.97), although the direction of effect was in the expected direction (ES = 0.42). Given that mean item scores on the IRP-10 range up to 6.0, teacher ratings for both groups reflected high levels of acceptability.

Overview of Outcomes

Means and standard deviations for each group on each outcome measure across the four measurement points are indicated in Table 3. Group × Time × Medication Status interaction effects were found on only one measure (i.e., parent ratings on the Negative/Ineffective Discipline factor of the PCRQ). Results of the tnixed effects analyses related to the Group × Time interactions are reported in Table 4. There was a significant Time effect on the majority of measures, as indicated in Table 4. For ptirposes of brevity, only significant interaction effects are described in the following.

Table 3.

Means and standard deviations for primary outcomes across four data collection periods

| FSS-EE |

CARE |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline |

Midpoint |

Post |

Follow-up |

Baseline |

Midpoint |

Post |

Follow-up |

|

| Measure | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) | M (SD) |

| FIQ | 2.04 (0.53) | 2.06 (0.55) | 2.14 (0.50) | 2.28 (0.43) | 2.18 (0.43) | 2.11 (0.47) | 2.22 (0.37) | 2.28 (0.41) |

| PES | 3.58 (0.70) | 3.73 (0.61) | 3.84 (0.50) | 3.88 (0.39) | 3.48 (0.55) | 3.61 (0.43) | 3.76 (0.58) | 4.00 (0.39) |

| PTIQ | 3.00 (0.59) | 3.16 (0.48) | 3.40 (0.34) | 3.02 (0.73) | 3.06 (0.51) | 3.34 (0.65) | 3.28 (0.64) | 3.23 (0.59) |

| PCRQ - N/ID | 2.88 (0.63) | 2.54 (0.51) | 2.37 (0.44) | 2.43 (0.51) | 2.98 (0.45) | 2.76 (0.45) | 2.70 (0.52) | 2.68 (0.46) |

| DPICS-CP-DO | 2.63 (2.32) | 4.81 (5.34) | 4.88 (4.23) | 3.86 (3.30) | 4.68 (3.78) | 4.75 (3.99) | 3.36 (3.08) | 4.15 (4.18) |

| DP1CS-CP-D0NT | 16.96 (9.20) | 13.10 (7.52) | 12.00 (5.18) | 13.86 (8.64) | 20.50 (8.27) | 21.71 (8.42) | 19.80 (7.76) | 20.62 (8.53) |

| DPICS-CU-DO | 3.17 (3.29) | 3.86 (4.28) | 5.18 (5.83) | 4.14 (2.48) | 5.43 (4.12) | 6.50 (5.15) | 4.00 (3.76) | 5.65 (4.09) |

| DPICS-CU-DONT | 21.25 (7.85) | 19.38 (8.81) | 18.47 (10.70) | 16.29 (5.68) | 27.61 (11.16) | 26.33 (10.14) | 20.00 (9.85) | 18.77 (6.62) |

| DPICS-CU-COM | 32.82 (20.22) | 35.75 (20.45) | 49.02 (25.51) | 45.28 (24.3) | 36.46 (18.73) | 34.28 (22.22) | 35.20 (26.37) | 44.67 (27.78) |

| SNAP - P | 1.66 (0.53) | 1.59 (0.44) | 1.38 (0.36) | 1.31 (0.44) | 1.79 (0.35) | 1.73 (0.49) | 1.61 (0.40) | 1.48 (0.54) |

| SNAP - T | 1.48 (0.72) | 1.34 (0.64) | 1.28 (0.59) | 1.12 (0.58) | 1.50 (0.53) | 1.47 (0.49) | 1.54 (0.49) | 1.47 (0.64) |

| ACES | 2.96 (0.50) | 3.23 (0.52) | 3.38 (0.57) | 3.39 (0.48) | 2.88 (0.51) | 3.09 (0.48) | 3.11 (0.50) | 3.25 (0.66) |

| STRS | 3.74 (0.62) | 3.76 (0.61) | 3.93 (0.50) | 3.77 (0.60) | 3.81 (0.60) | 3.72 (0.54) | 3.74 (0.50) | 3.75 (0.56) |

Note. FSS-EE = Family-School Success—Early Elementary; CARE = Coping With ADHD Through Relationships and Education; M= mean; SD = standard deviation; FIQ = Family Involvement Questionnaire; PES = Parent as Educator Scale; PTIQ = Parent-Teacher Involvement Questionnaire; PCRQ – N/ID = Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire – Negative/Ineffective Discipline; DPICS = Dyadic Parent-child Interaction Coding System (CP = child-led play, CU = cleanup, DO = do skills, DONT = don't skills, COM = child compliance); SNAP = Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham questionnaire; ACES = Academic Competence Evaluation Scale; STRS = Student-Teacher Relationship Scale.

Table 4.

Results of mixed effect analyses for the group × time interaction effects

| Post Treatment |

2 Month Follow-Up |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | df | F | p | ESa | df | F | p | ESa |

| FIQb, d | 1, 86 | 1.00 | 0.321 | 0.37 | 1, 128 | 3.39 | 0.068 | 0.65 |

| PESc, d | 1, 85 | 0.90 | 0.347 | 0.13 | 1, 128 | 0.06 | 0.804 | –0.24 |

| PTIQc | 1, 85 | 0.07 | 0.787 | 0.26 | 1, 127 | 0.00 | 0.962 | –0.13 |

| PCRQ - N/IDc, d | 1, 84 | 9.38 | 0.003 | 0.60 | 1, 126 | 6.15 | 0.015 | 0.43 |

| DPICS-CP-DOb | 1, 83 | 7.51 | 0.008 | 0.80 | 1, 123 | 5.32 | 0.023 | 0.60 |

| DPICS-CP-DONTc | 1, 83 | 0.77 | 0.383 | 0.41 | 1, 123 | 1.08 | 0.300 | 0.26 |

| DPICS-CU-DOb | 1, 83 | 8.01 | 0.006 | 0.66 | 1, 123 | 2.73 | 0.101 | 0.24 |

| DPICS-CU-DONTb, c, d | 1, 83 | 2.62 | 0.109 | –0.43 | 1, 123 | 2.85 | 0.094 | –0.36 |

| DPICS-CU-COMd | 1, 82 | 2.20 | 0.142 | 0.54 | 1, 121 | 0.20 | 0.660 | 0.07 |

| SNAP - Pc, d | 1, 85 | 0.63 | 0.430 | 0.15 | 1, 128 | 0.42 | 0.517 | –0.07 |

| SNAP - T | 1, 90 | 6.72 | 0.011 | 0.75 | 1, 132 | 4.34 | 0.039 | 0.84 |

| ACESc, d | 1, 80 | 0.55 | 0.461 | 0.36 | 1, 118 | 0.21 | 0.646 | –0.02 |

| STRS | 1, 91 | 5.00 | 0.028 | 0.54 | 1, 135 | 1.35 | 0.247 | 0.37 |

Note.

ES estimates were computed by comparing change scores between groups and dividing by the standard deviation of change scores for the treatment group (FSS-EE). Positive ES indicate larger improvements for FSS-EE participants as compared to CARE participants.

Analyses were conducted with adjustments for baseline differences between groups.

Time effect was significant at post treatment.

Time effect was significant at 2 month follow-up.

FIQ = Family Involvement Questionnaire; PES = Parent as Educator Scale; PTIQ = Parent-Teacher Involvement Questionnaire; PCRQ – N/ID = Parent-Child Relationship Questionnaire – Negative/Ineffective Discipline; DPICS = Dyadic Parent-child Interaction Coding System (CP = child-led play, CU = cleanup, DO = do skills, DONT = don't skills, COM = child compliance); SNAP = Swanson, Nolan, and Pelham questionnaire; ACES = Academic Competence Evaluation Scale; STRS = Student-Teacher Relationship Scale.

Effects on Family Involvement in Education

There were no significant differences between FSS-EE and CARE at postintervention and follow-up on any of the measures of family involvement in education, including the HQ, PES, and PTIQ.

Effects on Parenting Practices

On the Negative/Ineffective Discipline factor of the PCRQ, the three-way interaction of Group × Medication Status × Time was significant at postintervention; FSS was superior to CARE only for children on medication (ES = 2.10). At follow-up, the Group × Medication Status × Time effect was not significant, but the interaction of Group × Time was significant (FSS > CARE, ES = 0.43).

With regard to the DPICS, the Group × Time effect was significant for “Do” skills in both the child-led play and the cleanup situations, but not for “Don't” skills on these tasks. For child-led play. Do skills were stronger for families in FSS-EE than those in CARE both at postintervention (ES = 0.80) and follow-up (ES = 0.60). For the cleanup task. Do skills were superior for those in FSS-EE at postintervention only (ES = 0.66).

Effects on Child Functioning in the Family

There were no differences between FSS-EE and CARE at postintervention and follow-up on parent ratings of ADHD and ODD symptoms on the SNAP-IV as well as direct observations of child compliance on the DPICS cleanup task.

Effects on Child Functioning at School

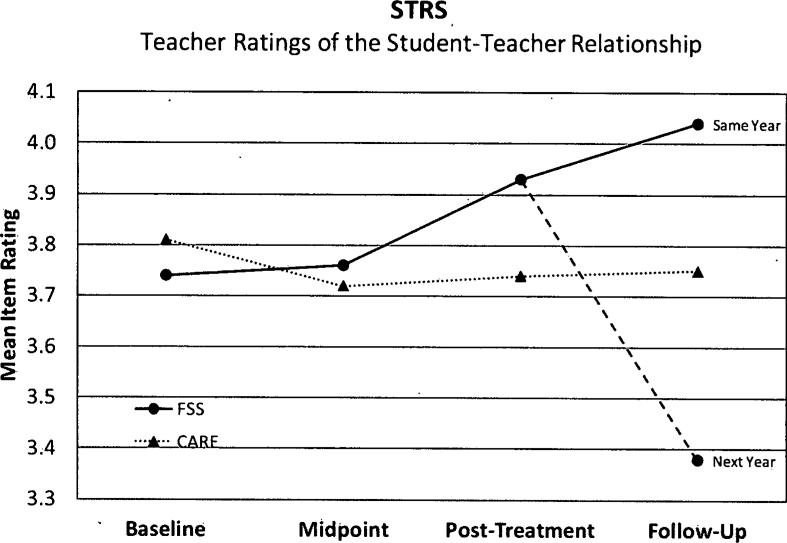

FSS-EE was superior to CARE on teacher ratings of ADHD and ODD symptoms on the SNAP-IV at both postintervention (ES = 0.75) and follow-up (ES = 0.84). Also, FSS-EE was superior to CARE for the STRS at postintervention (ES = 0.54), but not at follow-up. A post hoc analysis of STRS ratings at follow-up indicated significant differences within the FSS-EE group for children who received follow-up during the same year as the intervention (with the same teacher; n = 10) as opposed to those who were followed the next year (with a different teacher; n = 7; p = .018; ES = 0.97). This seasonal effect at follow-up was not significant for children in the CARE group (ES = 0.21). See Figure 2 for an illustration.

Figure 2.

Illustration of STRS teacher ratings at follow-up. There were significant differences within the FSS-EE group for children who received follow-up with the same teacher as opposed to those who were followed the next year (with a different teacher). Seasonal effect at follow-up was not significant for children in the CARE group. STRS = Student-Teacher Relationship Scale; FSS-EE = Family-School Success—Early Elementary; CARE = Coping with ADHD through Relationships and Education.

Discussion

This study provides strong evidence of the acceptability of FSS-EE and offers preliminary support for the effectiveness of this intervention for young elementary-age students. Parents and teachers who participated in FSS-EE reported high levels of acceptability, and from the perspective of parents, FSS-EE was more acceptable than a program providing education and support (CARE). In addition, the results suggested that FSS-EE may be more effective than education and support in improving parenting practices, strengthening the student-teacher relationship, and reducing child behavior problems in school. This study replicates studies showing that interventions with a substantial parent-mediated component are effective in improving school as well as family functioning (Eyberg, Nelson, & Boggs, 2008; Fabiano et al., 2009). It is noteworthy that the effectiveness of FSS-EE was demonstrated in relation to an active control condition that received an alternative treatment that was highly acceptable to parents and may have been effective in improving numerous outcome variables. This study is one of the few to compare behavioral intervention to an alternative, active intervention (Pelham & Fabiano, 2008).

The results demonstrated that FSS-EE may be effective in improving student-teacher relationships and reducing teacher ratings of child behavior problems. The specific mechanism of action for the effect on school factors requires additional study. Nonetheless, it is reasonable to hypothesize that the use of family–school consultation (CBC) and the implementation of DRCs in the classroom may have had an effect on child behavior in school and the quality of the student–teacher relationship (Owens et al., 2008; Sheridan et al., 2012). In addition, improvements in parenting practices may improve the quality of the parent–child relationship, which in turn contributes to improved child self-regulation in school (Healey, Gopin, Grossman, Campbell, & Halperin, 2010; Pianta, 1997).

The findings at follow-up related to teacher ratings of the student–teacher relationship suggest that the effect of FSS-EE may not carry over to the following year when the student has a different teacher. Although sample sizes were small, this result suggests the need for a booster intervention early in the following school year that involves the family and new teacher.

Contrary to expectation, FSS-EE did not have an effect on measures of family involvement in education. However, there were significant Time effects on measures of family involvement (FIQ, PES, PTIQ), suggesting the possibility that both FSS-EE and CARE were effective at improving family involvement. Given that the study did not include a no-treatment control group, it was not possible to determine the effects of CARE. Nonetheless, FSS-EE was designed specifically to have an effect on family involvement in education, and it was anticipated that this intervention would be more effective than CARE. Recently, an intervention similar to FSS-EE, developed for older elementary students (i.e., FSS for students in Grades 2–6), was shown to have an effect on family involvement in education (Power et al., 2012). A noteworthy difference between FSS-EE and FSS is that FSS targeted child homework performance and provided highly systematic skills training in this area. In contrast, FSS-EE did not include a strong focus on homework. FSS-EE provided parents with education about family involvement in schoohng (e.g., suggestions to reduce screen time and increase time spent in shared reading and natural learning opportunities, parent tutoring strategies), but there was less of an emphasis on skills training in this area with FSS-EE as there was with FSS. Also, it should be noted that parent adherence to the suggested parent tutoring strategies was low, as indicated by low rates of completion of the homework assignment related to parent tutoring. Future research with FSS-EE may incorporate more systematic training related to family involvement in education, such as homework skills training (Power et al., 2001) and dialogic reading (Zevenbergen & Whitehurst, 2003). In addition, implementation supports may be necessary to encourage consistent use of FSS-EE strategies.

The findings suggested that, similar to many parent training programs, FSS-EE has an effect on parenting practices. FSS-EE was superior to CARE in improving Do skills in both the child-led play and cleanup situations, based on direct observations of parenting behavior. This finding is noteworthy in that the use of Do skills during cleanup tasks has been found to be negatively associated with the emergence of conduct problems later in childhood (Chronis et al., 2007). Other studies have demonstrated an effect of parent training on Don't skills as well as Do skills (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007; Bagner, Sheinkopf, Vohr, & Lester, 2010). In this study, even though FSS-EE was not superior to CARE with regard to reducing Don't skills, it was noted that there was a significant Time effect on Don't skills in both the play and cleanup situations.

In general, the effect of intervention did not vary as a function of medication status. The three-way interaction of Group × Time × Medication status was significant on only one measure (PCRQ, Negative/Ineffective Discipline factor), but this was the case at postintervention and not follow-up. Admittedly, sample sizes were relatively small, but the failure to detect a three-way interaction effect involving medication was found in a similar study of FSS focused on an older group of students (Power et al., 2012). Nonetheless, additional research is needed to examine the potential for medication to exert a moderating influence on response to behavioral treatment, specifically a family–school intervention.

Several litnitations deserve attention. First, the sample size was relatively small, which limited the power of the analyses to detect effects that were not large. Second, it should be noted that acceptability ratings were obtained only from families who completed the two programs and returned for post-treatment data collection (75% for FSS-EE and 86% for CARE). Third, as indicated in Figure 1, attrition was somewhat higher for FSS-EE than for CARE. This pattern was more noticeable at follow-up. It is not clear why this was the case, because attendance was high for both groups and parent ratings of acceptability were higher for FSS-EE than CARE. In addition, in a larger study evaluating FSS for older students (Power et al., 2012), attrition was relatively low and did not differ between the intervention and comparison groups. The effect of this pattern on the findings is not known, but it is possible that the higher attrition in FSS-EE may have magnified the extent of the group differences especially at follow-up. As such, the findings of this preliminary study need to be interpreted with caution.

Fourth, it is possible that there were differences between groups with regard to nonspecific intervention effects, even though CARE provided a control for many of these factors. For example, the groups may have differed with regard to group dynamics and the quality of the relationship between clinician and families. Although acceptability findings and our observations of families strongly indicated that the alliance between family and clinician was strong for both groups, it is possible that group differences in therapeutic alliance may have had an effect on treatment effects (Kazdin & Whitley, 2006). Fifth, families participating in this study generally were highly motivated. For the most part, families were self-referrals. Further, families proceeded through multiple gates of screening and evaluation before the psychosocial phase of the study was initiated. As such, families difficult to engage in treatment likely were underrepresented in this study. Sixth, this study was conducted primarily in a clinic setting. Given the advantages of school-based service delivery with regard to improving access to care and affording opportunities for classroom interventions, it is recommended that this intervention be adapted for use in school settings. Further, data were not collected regarding parent and teacher use of behavioral interventions prior to the start of the study; therefore, the FSS-EE and CARE groups cannot be compared for baseline intervention exposure. Finally, this exploratory study examined follow-up effects 2 school months after intervention. It is important to investigate longer term effects, as well as to explore the potential benefits of booster sessions, especially when students transition into the next grade level.

In conclusion, this intervention development study provided evidence of the acceptability and feasibility of FSS-EE. The findings offer preliminary support for the effectiveness of this intervention in improving parenting practices and student functioning in school among young students with ADHD. In addition, the findings suggest the need to provide more systematic training to families regarding strategies to promote their children's education. In the future, an evaluation of FSS-EE with larger, more diverse samples of children is needed. It is possible that modifications to the FSS-EE model will be required (e.g., additional implementation supports, strategies to increase family engagement in intervention) to address the unique needs of low-income families who often face challenges accessing and maintaining engagement in mental health treatment (Kataoka, Zhang, & Wells, 2002; Power, Lavin, Mautone, & Blum, 2010). Also, it is recommended that FSS-EE be adapted for use in schools and that a back-to-school component be added to assist students during the transition to the next grade level the following year.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by Research Grant R34MH080782, funded by the National Institute of Mental Health, awarded to the senior author (Thomas Power). The authors thank the participating families and schools as well as the clinicians and research assistants involved in the project, including Kristen Caprara, Michael Cassano, Tracy Costigan, Rebecca Gullan, Jenelle Nissley-Tsiopinis, Elizabeth Ellis Ohr, Katy Tresco, Jennifer Brereton, Sean Cleary, Élizabeth Gallini, Shawn Gilroy, Jessica Gresko, Margaret Howley, Lauren Lee, Brittany Lyman, Celeste Malone, Sean O'Dell, Lynn Panepinto, Timothy Pian, Elyss Pickenheim, Sarah Robins, and Brittany Whitehead.

Biography

Jennifer A. Mautone, PhD, is a clinical and research psychologist in the Center for Management of ADHD/Community Schools Program at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. Her research interests focus on developing and evaluating multisystemic intervetitions (i.e., interventions involving the family, school, and health system) for children and families coping with ADHD.

Stephen A. Marshall, MS, is currently a student in the clinical psychology doctoral program at Ohio University and a research coordinator for the Center for Intervention Research in Schools. His research interests focus on enhancing intervention and diagnostic practices for youth and adults with attention and learning problems.

Jaclyn Sharman, MS, is a clinical research coordinator at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. She has extensive experience in the management of large-scale, publicly and privately funded research studies and particular expertise related to clinical research in hospital, primary care, and school settings.

Ricardo B. Eiraldi, PhD, is an assistant professor of clinical psychology in the Department of Pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. His research focuses on the clinical presentation of ADHD in ethnically diverse children; the application of help-seeking behavior models in the study of health disparities; and the development of strategies for addressing mental health services disparities in the inner city.

Abbas Jawad, PhD, is an associate professor of biostatistics in pediatrics at the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. He has extensive experience in • coordinating statistical analysis for large clinical studies, with particular expertise in the methodology of repeated measures and longitudinal studies, measurement errors, and the effect of initial measurement on the estimation of treatment effect. He has served as a key investigator on numerous studies involving psychosocial intervention development and evaluation in schools and clinical settings.

Thomas J. Power, PhD, is a professor of school psychology in pediatrics, psychiatry, and education at the University of Pennsylvania, as well as director of the Center for Management of ADHD and chief psychologist at The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia. He has received funding from the National Institute of Mental Health, the Department of Education, and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau to conduct research on multisystemic interventions for children with ADHD. He is past editor of School Psychology Review.

Contributor Information

Jennifer A. Mautone, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Stephen A. Marshall, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia

Jaclyn Sharman, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia.

Ricardo B. Eiraldi, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia/Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Abbas F. Jawad, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia/Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

Thomas J. Power, The Children's Hospital of Philadelphia/Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania

References

- Abikoff H, Hechtman L, Klein RG, Weiss G, Fleiss K, Etcovitch J, Pollack S. Symptomatic improvement in children with ADHD treated with long-term methylphenidate and multimodal psychosocial treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry. 2004;43:802–811. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000128791.10014.ac. doi; 10.1097/01.chi.0000128791.10014.ac. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ambrosini PJ. Historical development and present status of the Schedule for Affective Disorders and Schizophrenia for School-Age Children (K-SADS). Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2000;39:49–58. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200001000-00016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Eyberg SM. Parent-child interaction therapy for disruptive behavior in children with mental retardation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:418–429. doi: 10.1080/15374410701448448. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Sheinkopf SJ, Vohr BR, Lester BM. Parenting intervention for externalizing behavior problems in children born premature: An initial examination. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 2010;31:209–216. doi: 10.1097/DBP.0b013e3181d5a294. doi:10.1097/DBP.ObO13e3181d5a294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Christenson SL, Reschly AL, editors. Handbook of school-family partnerships. Routledge; New York, NY: 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Christenson SL, Sheridan SM. Schools and families: Creating essential connections for learning. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Chronis AM, Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Jr., Williams SH, Baumann BL, Kipp H, Rathouz PJ. Maternal depression and early positive parenting predict future conduct problems in young children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Developmental Psychology. 2007;43:70–82. doi: 10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.70. doi:10.1037/0012-1649.43.1.70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corcoran J, Dattalo P. Parent involvement in treatment for ADHD: A meta-analysis of the published studies. Research on Social Work Practice. 2006;16:561–570. doi:10.1177/1049731506289127. [Google Scholar]

- DiPerna JC, Elliott SN. Academic competence evaluation scales. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 2000. [Google Scholar]

- DiPerna JC, Volpe RJ, Elliott SN. A model of academic enablers and elementary reading/language arts achievement. School Psychology Review. 2002;31:298–312. [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, McGoey KE, Eckert TL, Van-Brakle J. Preschool children with attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder: Impairments in behavioral, social, and school functioning. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:508–515. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200105000-00009. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200105000-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DuPaul GJ, Power TJ, Anastopoulos AD, Reid R. The ADHD rating scale—IV: Checklists, norms, and clinical interpretation. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Egger HL, Kondo D, Angold A. The epidemiology and diagnostic issues in preschool attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Infants and Young Children. 2006;19:109–122. [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Boggs SR. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents with disruptive behavior. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:215–237. doi: 10.1080/15374410701820117. doi:10.1080/15374410701820117. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Duke M, Boggs SR. Manual for the dyadic parent-child interaction coding system. (3rd ed.) 2004 Retrieved from http://www.pcit.org.

- Fabiano GA, Pelham WE, Jr., Coles EK, Gnagy EM, Chronis-Tuscano A, O'Connor BC. A meta-analysis of behavioral treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Clinical Psychology Review. 2009;29:129–140. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2008.11.001. doi:10.1016/j.cpr.2008.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fantuzzo J, Tighe E, Childs S. Family Involvement Questionnaire: A multivariate assessment of family participation in early childhood education. Journal of Educational Psychology. 2000;92:367–376. doi: 10.1037/0022-0663.92.2.367. [Google Scholar]

- Ferriero E, Teberosky A. Literacy before schooling. Heinemann Educational Books; Portsmouth, NH: 1982. [Google Scholar]

- Furman W, Giberson RS. Identifying the links between parents and their children's sibling relationships. In: Shuman S, editor. Close relationships in social-emotional development. Ablex; Norwood, NJ: 1995. pp. 95–108. [Google Scholar]

- Graziano PA, Reavis RD, Keane SP, Calkins SD. The role of emotion regulation in children's early academic success. Journal of School Psychology. 2007;45:3–19. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2006.09.002. doi: 10.1037/0022-3514.51.6.11733806354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhill LL, Posner K, Vaughan BS, Kratochvil CJ. Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in preschool children. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America. 2008;17:347–366. ix. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.004. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2007.11.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Healey DM, Gopin CB, Grossman BR, Campbell SB, Halperin JM. Mother-child dyadic synchrony is associated with better functioning in hyperactive/inattentive preschool children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry. 2010;51:1058–1066. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02220.x. doi: 10.1111/J.1469-7610.2010.02220.X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hollingshead AB. Four factor index of social status. Yale University Department of Sociology; New Haven, CT: 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Hoover-Dempsey KV, Bassler OC, Brissie JS. Explorations in parent-school relations. Journal of Educational Research. 1992;85:287–294. [Google Scholar]

- Kataoka SH, Zhang L, Wells KB. Unmet need for mental health care among U.S. children: Variation by ethnicity and insurance status. American Journal of Psychiatry. 2002;159:1548–1555. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.159.9.1548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kazdin AE, Whitley MK. Pretreatment social relations, therapeutic alliance, and improvements in parenting practices in parent management training. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2006;74:346–355. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.74.2.346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelley ML, Heffer RW, Gresham FM, Elliott SN. Development of a modified treatment evaluation inventory. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment. 1989;11:235–247. doi:10.1007/bfD0960495. [Google Scholar]

- Kern L, DePaul G, Volpe R, Sokol N, Lutz G, Arbolino L, VanBrakle J. Multisetting assessment-based intervention for young children at risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder: Initial effects on academic and behavioral functioning. School Psychology Review. 2007;36:237–255. [Google Scholar]

- Kohl GO, Lengua LJ, McMahon RJ, Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Parent involvement in school: Conceptualizing multiple dimensions and their relations with family and demographic risk factors. Journal of School Psychology. 2000;38:501–523. doi: 10.1016/S0022-4405(00)00050-9. doi:10.1016/s0022-4405(00)00050-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Hartung CM, Loney J, Pelham WE, Chronis AM, Lee SS. Are there sex differences in the predictive validity of DSM-IV ADHD among younger children? Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2007;36:113–126. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274066. doi: 10.1080/15374410701274066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lahey BB, Pelham WE, Loney J, Kipp H, Ehrhardt A, Lee SS, Massetti G. Three-year predictive validity of DSM-IV attention deficit hyperactivity disorder in children diagnosed at 4-6 years of age. The American Journal of Psychiatry. 2004;161:2014–2020. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.161.11.2014. doi:10.1176/appi.ajp.l61.11.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Langberg JM, Arnold LE, Flowers AM, Epstein JN, Altaye M, Hinshaw SP, Jensen PS. Parent-reported homework problems in the MTA Study: Evidence for sustained improvement with behavioral treatment. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2010;39:220–233. doi: 10.1080/15374410903532700. doi:10.1080/15374410903532700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee SS, Lahey BB, Owens EB, Hinshaw SP. Few preschool hoys and girls with ADHD are well-adjusted during adolescence. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2008;36:373–383. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9184-6. doi: 10.1007/s10802-007-9184-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyon AR, Budd KS. A community mental health implementation of parent-child interaction therapy (PCIT). Journal of Child and Family Studies. 2010;19:654–668. doi: 10.1007/s10826-010-9353-z. doi: 10.1007/S10826-010-9353-Z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mautone JA, Lefler EK, Power TJ. Promoting family and school success for children with ADHD: Strengthening relationships while building skills. Theory into Practice. 2011;50:43–51. doi: 10.1080/00405841.2010.534937. doi:10.1080/00405841.2011.534937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Murphy CE, Richerson L, Gido EL, Himawan LK. Science to practice in underserved communities: The effectiveness of school mental health programming. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:434–447. doi: 10.1080/15374410801955912. doi: 10.1080/15374410801955912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Owens JS, Storer JL, Girio-Herrera E. Psychosocial interventions for elementary school-aged children with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In: Evans S, Hoza B, editors. Treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (pp. Civic Research Institute; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 10–12.pp. 10–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pelham WE, Fabiano GA. Evidence-based psychosocial treatments for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology. 2008;37:184–214. doi: 10.1080/15374410701818681. doi:792185156[pii]10.1080/15374410701818681. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfiffner LJ, Mikami AY, Huang-Pollock C, East-erlin B, Zalecki C, McBurnett K. A randomized, controlled trial of integrated home-school behavioral treatment for ADHD, predominantly inattentive type. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2007;46:1041–1050. doi: 10.1097/chi.0b013e318064675f. doi: 10.1097/chi.ObO13e313064675f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Adult-child relationship processes and early schooling. Early Education and Development. 1997;8:11–26. [Google Scholar]

- Pianta RC. Student-teacher relationship scale: Professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources; Odessa, FL: 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Hess LE, Bennett DS. The acceptability of interventions for attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder among elementary and middle school teachers. Journal of Developmental and Behavioral Pediatrics. 1995;16:238–243. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Karustis JL, Habboushe D. Homework success for children with ADHD: A family-school intervention program. Guilford Press; New York, NY: 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Lavin HJ, Mautone JA, Blum NJ. Partnering to Achieve School Success: A collaborative care model of early intervention for attention and behavior problems in urban contexts. In: Doll B, Pfohl W, Yoon J, editors. Handbook of youth prevention science. Routledge; New York, NY: 2010. pp. 375–392. [Google Scholar]

- Power TJ, Mautone JA, Soffer SL, Clarke AT, Marshall SA, Sharman J, Blum NJ, Jawad AF. A family-school intervention for children with ADHD: Results of a randomized clinical trial. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology. 2012;80:611–623. doi: 10.1037/a0028188. doi:10.l037/a0028188. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds CR, Kamphaus RW. BASC- 2, Behavior assessment system for children. 2nd ed. Circle Pines, MN: AGS Publishing; 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Rimm-Kaufman S, Pianta RC. Family-school communication in preschool and kindergarten in the context of a relationship-enhancing intervention. Early Education and Development. 2005;16:287–316. [Google Scholar]

- Rogers MA, Wiener J, Marton I, Tannock R. Parental involvement in children's learning: Comparing parents of children with and without attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Journal of School Psychology. 2009;47:167–185. doi: 10.1016/j.jsp.2009.02.001. doi:10.1016/j.jsp.2009.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanetti LMH, Kratochwill TR. Toward developing a science of treatment integrity: Introduction to the special series. School Psychology Review. 2009;38:445–459. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan SM, Bovaird JA, Glover TA, Garbacz SA, Witte A, Kwon K. A randomized trial examining the effects of conjoint behavioral consultation and the mediating role of the parent-teacher relationship. School Psychology Review. 2012;41:23–46. [Google Scholar]

- Sheridan SM, Kratochwill TR. Conjoint behavioral consultation: Promoting family-school connections and interventions. 2nd ed. Springer Science + Business Media; New York, NY: 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Spira EG, Fischel JE. The impact of preschool inattention, hyperactivity, and impulsivity on social and academic development: A review. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines. 2005;46(7):755–773. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01466.x. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01466.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Swanson JM, Kraemer HC, Hinshaw SP, Arnold LE, Conners CK, Abikoff HB, Wu M. Clinical relevance of the primary findings of the MTA: Success rates based on severity of ADHD and ODD symptoms at the end of treatment. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry. 2001;40:168–179. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200102000-00011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D. WASI: Wechsler Abbreviated Scales of Intelligence. The Psychological Corporation; San Antonio, TX: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Wells KC, Pelham WE, Kotkin RA, Hoza B, Abikoff HB, Abramowitz A, Schiller E. Psychosocial treatment strategies in the MTA : Rationale, methods, and critical issues in design d implementation. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology. 2000;28:483–505. doi: 10.1023/a:1005174913412. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willford AP, Shelton TL. Psychosocial treatments for preschoolers at-risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder. In: Evans S, Hoza B, editors. Treating attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder. Civic Research Institute; New York, NY: 2011. pp. 9–2.pp. 9–16. [Google Scholar]

- Zevenbergen AA, Whitehurst GJ. Dialogic reading A shared picture book reading intervention for preschoolers. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; Mahwah, NJ: 2003. [Google Scholar]