Significance

In the history of mechanical engineering, it is commonly believed that transporting huge stones with sliding sledges hauled by men did not occur in ancient China, because there were well-developed wheeled vehicles in China around 1500 B.C. However, some books contain brief remarks that the Large Stone Carving in the Forbidden City in Beijing was pulled to the site with a sledge sliding on an artificial ice path. Here we investigate the Chinese case based on historical documents and modern experimental results. We demonstrate that wood-on-ice sliding is more reliable and efficient than other lubrication methods, and pouring water on the contact surface is necessary to make this type of transport feasible.

Abstract

Lubrication plays a crucial role in reducing friction for transporting heavy objects, from moving a 60-ton statue in ancient Egypt to relocating a 15,000-ton building in modern society. Although in China spoked wheels appeared ca. 1500 B.C., in the 15th and 16th centuries sliding sledges were still used in transporting huge stones to the Forbidden City in Beijing. We show that an ice lubrication technique of water-lubricated wood-on-ice sliding was used instead of the common ancient approaches, such as wood-on-wood sliding or the use of log rollers. The technique took full advantage of the natural properties of ice, such as sufficient hardness, flatness, and low friction with a water film. This ice-assisted movement is more efficient for such heavy-load and low-speed transportation necessary for the stones of the Forbidden City. The transportation of the huge stones provides an early example of ice lubrication and complements current studies of the high-speed regime relevant to competitive ice sports.

Transporting heavy objects has a history of thousands of years, from moving enormous statues weighing tens of tons in early civilizations (1) to relocating entire buildings, more than 15,000 tons, in modern societies (2). Lubrication plays a crucial role in reducing friction to make such transport possible. In the early history of lubrication, there are two well-documented milestones of the transport of heavy stones (1): (i) lubricant was used for wood-on-wood sliding at Saqqara Egypt ca. 2400 B.C. and (ii) the aid of log rollers was used at Kouyunjik Assyria ca. 700 B.C.; rolling is usually considered a superior system over sliding for the ancient cases (1, 3). Although in China spoked wheels appeared ca. 1500 B.C. (1, 3), we noticed that in the 15th and 16th centuries sliding sledges were still used in transporting huge stones (over 100 tons) to the Forbidden City in Beijing (4, 5).

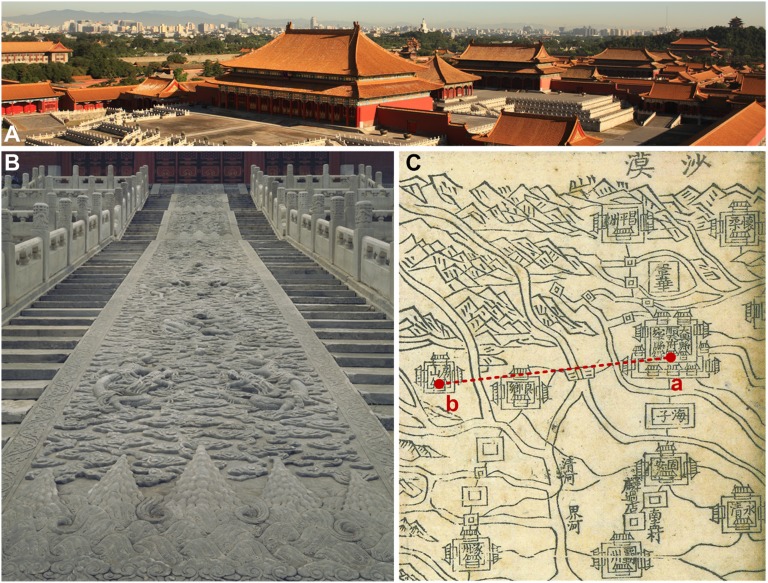

The Forbidden City is a unique historical symbol of China (4, 6); it not only represented the supreme imperial power of the Ming and Qing Dynasties for about 500 y until 1911, but it also provides enormous and valuable information of the history and culture of China during the 15th–19th centuries. Massive numbers of large stones were mined and transported to the Forbidden City (Fig. 1A and SI Materials and Methods) for its construction in the 15th and 16th centuries, including the Large Stone Carving, which weighs more than 300 tons (Fig. 1B and SI Materials and Methods). It is briefly mentioned in some books that the Large Stone Carving was transported to the site in deep winter with sledges sliding on an artificial ice path (4, 5), although to the best of our knowledge this transport has never been investigated in detail or from a scientific point of view. We have not been able to locate any historical record about the transportation details of the Large Stone Carving. However, we learned by translating a 500-y-old Chinese document (7), which recorded similar information (although apparently different in detail from statements made in books; a translation is given in SI Materials and Methods), that in 1557 a large stone with the dimensions of 9.6 × 3.2 × 1.6 m (∼123 tons) was transported over 70 km in 28 d to the Forbidden City with a sliding sledge hauled by a team of men. A map published in 1573–1620 (8) shows the approximate path of transport from the quarry to the Forbidden City (Fig. 1C).

Fig. 1.

The Forbidden City and the huge stones. (A) Palaces in the Forbidden City (Palace Museum, www.dpm.org.cn). Wooden-structure buildings were built on broad and tall stone bases, with stone stairs leading up to the entrance of each building. (B) The Large Stone Carving (Palace Museum, www.dpm.org.cn), the heaviest stone in the Forbidden City, is located behind the current Hall of Preserving Harmony (Baohe Dian) between two paths of stone stairs; it is commonly believed to have been more than 300 tons when it was first transported to the site in 1407–1420. (C) The distance between the Forbidden City (a) and the Dashiwo Quarry in Fangshan (b) is about 70 km. The double lines on the map (8) represent rivers and single lines represent roads.

However, this transport of such a large stone is in contrast with the common understanding of the history of mechanical engineering, which is that “the haulage of colossal statues by masses of men does not appear in any kind of ancient Chinese representation” (1, 3) because there were large vehicles with “elegantly constructed spoked wheels” by ca. fourth century B.C. in China (1, 3). Consequently, we became curious about three questions: (i) Why was a sliding sledge still used when large wheeled vehicles had been well developed in China for about 2,000 years? (ii) Was it a good choice to transport huge stones with a sledge sliding on an artificial ice path compared with other lubrication methods? (iii) What were the special features of the ice lubrication technique used in Beijing (latitude 40°N)? Here we investigate the transportation method from the standpoint of engineering, based on the limited information from the modern literature (4, 5) and the historical document (7) and demonstrate that an ice lubrication technique of water-lubricated wood-on-ice sliding was likely applied in transportation by the ancient Chinese, with recognition of the reliability of sliding over rolling in such heavy-load and low-speed conditions.

Sliding or Rolling?

Actually, both sliding sledges and wheeled vehicles were used to transport heavy stones to the Forbidden City in the 15th and 16th centuries. For example, when planning the transportation of huge stones for the construction of the Forbidden City around 1596 there were debates over whether to use sledges or wheeled vehicles (see the translation of ref. 7 in SI Materials and Methods), which has not been noted in the modern literature (3–5). Although transportation with sledges required many more hired peasants and much more time and money than that with mule-powered wheeled vehicles, the sledges were a safer and more reliable method for the huge stones, whose mining had already been expensive (7). In fact, we argue that the sledges were needed for the huge stones, which were beyond the load capacity of the wheeled vehicles of that time (up to 95 tons by 1596, SI Materials and Methods). Lubrication played a critical role to make this transportation with sledges possible.

There are two typical lubrication methods to reduce friction when a sliding sledge is used: sliding with the aid of a lubricant and movement with the aid of rollers. Typical examples using different lubrication methods for transporting heavy objects with sliding sledges are listed in Table 1, where μ is the coefficient of kinetic friction estimated from the known data in the table (Materials and Methods), m is the mass of the object, and s is the distance of transport.

Table 1.

Heavy objects transported with sledges using different lubrication methods

| Case | Year | Object | Location | m, tons | s, km | Method | Lubricant | Power | μ |

| 1 | ca. 1880 B.C. | Statue of Tehuti-Hetep | El-Bersheh, Egypt | 60 | Unknown | Sliding on wooden planks | Water | 172 men | 0.23 |

| 2 | ca. A.D. 400 | A stone | Japan | 14 | Unknown | Log rollers on a dirt road | Oil | 36 men | 0.21 |

| 3 | A.D. 1557 | A stone | Beijing, China | 123 | 70 | Sliding on ice | ? | A team of men | ? |

| 4 | A.D. 1934 | Mining equipment | Far north, Canada | 28 | 212.4 | Sliding on ice | None | A tractor | 0.36 |

| 5 | A.D. 1999 | Cape Hatteras Lighthouse | North Carolina | 4,400 | 0.884 | Steel roller on steel tracks | Soap bar | Five 30-ton jacks | <0.03 |

We include in Table 1 (case 2) data from experimental results from sliding a fifth-century sledge (9), which was reproduced in 1978. Although the value of μ for rolling in case 2 is slightly lower than that for sliding in case 1, it is difficult to control the advancing direction with log-roller-aided sliding when the moving route is not straight (10), because the log rollers will be left behind the advancing sledge and so need to be relocated to the front and aligned normal to the advancing direction all along the transportation route. Also, the application of log rollers, similar to the application of wheeled vehicles, would be limited by the condition of the road (3, 7), such as its flatness and ability to support the load.

It should be noted that the value of μ for log rollers rolling on a dirt road in the ancient case (case 2) was much higher than that of steel rollers rolling on steel tracks in modern cases, such as case 5 (11), as a consequence of the strength of the contact materials. The estimated values of μ for the heavy transportation of case 2 and case 5 can also be verified by the experimental results for transporting a 30-ton stone with a duplicated fifth-century sledge (12), where μ = 0.2–0.4 for the case of the log rollers directly rolling on the ground and μ = 0.02–0.04 for the case of the log rollers rolling on the rails of wooden rods. Therefore, given the sledge-on-ice transport over the long distance of 70 km (case 3), lubricated sliding should have been more practical and reliable for the heaviest of loads than rolling in ancient times, which may be the reason that the Chinese chose sliding instead of rolling.

Sliding on Ice

Another important reason for the Chinese to adopt the sliding sledge is that wood-on-wood sliding could be substituted with wood-on-ice sliding, where the ice layer on a road provides sufficient hardness and flatness instead of the wooden planks laid on the ground, as in the ancient Egyptian case (1) (case 1 in Table 1). Compared with the warm weather in Egypt, northern China has a frozen winter with the natural possibility for formation of ice, the advantages of which have been demonstrated by many applications in the far northern areas, such as Scandinavia, Russia, and northern Canada (13) (e.g., case 4 in Table 1; Materials and Methods). Because the transportation of the enormous stones to the Forbidden City took place in late December after the winter solstice (7) (December 22 ± 1 d) to the following January, the temperature conditions should have allowed an artificial ice path to be created on the ground. For example, the average temperature in Beijing in January was about –3.7 ± 0.5 °C in the 15th and 16th centuries (Materials and Methods). Although there was no river or canal along the route for the transport (Fig. 1C), wells were dug every half kilometer along the road for the water supply for watering and running the sledge, according to the statements we translated from a historical document (7). These conclusions are consistent with the modern literature that pouring water on the ground provides an ice surface for transportation (4, 5). In addition, the strength of an artificial ice path on the ground would be sufficient to support a sledge with a 300-ton stone. In support of this conclusion we cite the latest successful case of moving an entire 1,200-ton building of the Anda Railway Station (latitude 45°N) on an artificial ice path during the period from January 14 to February 4, 2013, in Heilongjiang Province, China (14).

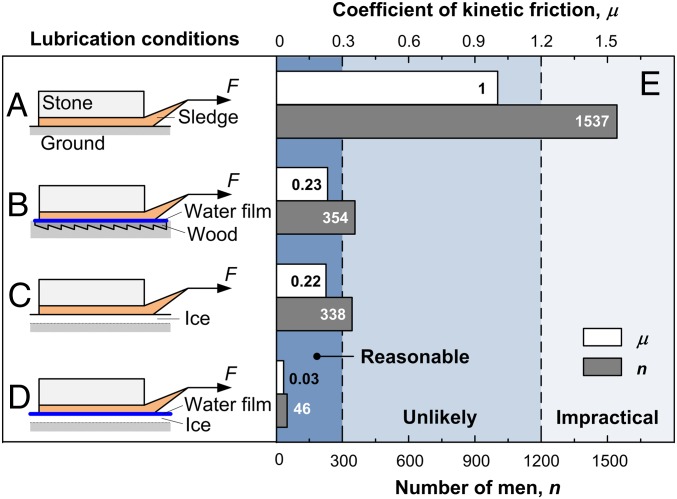

Water can also be used as the lubricant in wood-on-ice sliding, and below we demonstrate that this water lubrication is an important factor that makes possible the transportation of the huge stones. Taking case 3 (7) as a typical example, we estimated the number of men n needed for towing a sledge with a 123-ton stone under different lubrication conditions (Materials and Methods), and the results are listed in Fig. 2. The coefficient of friction μ is estimated with the data from typical examples in the literature (1, 12, 15). Here we consider a reasonable estimate as n < 300 men, whereas the cases with n > 1,200 men are considered impractical (Materials and Methods). Obviously, the result of n > 1,500 men makes simple sliding without any lubrication (Fig. 2A) impractical. Although the result of n = 354 men for the lubricated wood-on-wood sliding (Fig. 2B) is close to our criterion of n < 300 men, the same lubrication method will likely be unsuccessful when applied to transporting heavier stones, such as the Large Stone Carving of ∼300 tons.

Fig. 2.

Estimate of the number of men n needed to pull a sledge with a 123-ton stone corresponding to four different lubrication conditions: (A) sliding on a dirt road (12), (B) sliding on wet wood (1), (C) sliding on an ice path without a lubricating water film (15), and (D) Sliding on an iced road with a lubricating water film (15). F is the towing force. (E) Comparison of the coefficient of the friction μ and the number of men n needed for conditions A–D.

Two different cases of ice lubrication are illustrated in Fig. 2 C and D. Although ice friction is usually very low, as shown in ice sports such as skating and curling, the coefficient of friction on ice varies from 0.01 to 0.43 as reported by the experimental results under different configurations (16). The value of μ on ice is affected by many factors, including temperature, sliding velocity, materials, contact area, and roughness. The sliding velocity is a significant factor for temperatures <0 °C (16). For example, the experimental results in ref. 15 showed that the value of μ between lacquered wood and ice at −10 °C is 0.36 at 3 cm/s without a lubricating water film (Fig. 2C) but is 0.03 at 5 m/s with the formation of a water film by frictional heating (Fig. 2D); in the far north, case 4 (13) in Table 1 is a typical case for dry wood-on-ice sliding.

The value of μ on ice at a low speed of several centimeters per second is also sensitive to the temperature. For example, the value of μ for dry wood-on-ice sliding at −4 °C is μ ≈ 0.22 (15). Here, regarding the average temperature of −3.7 °C for the ancient Chinese case, we take the value μ ≈ 0.22 for the case in Fig. 2C, which is similar to that for lubricated wood-on-wood sliding, and the resulting value of n of dry wood-on-ice sliding is also beyond the reasonable range of 300 men. Therefore, among all of the lubrication conditions in Fig. 2E, lubricated wood-on-ice sliding (Fig. 2D) should be appropriate for the transportation of a stone with a mass of 123 tons and above, and the generation of a lubricating water film is necessary for the transportation.

Lubricating Water Film

Based on the distance and the estimated time for the stones to be transported to the Forbidden City (case 3 in Table 1), we evaluate the average sliding speed of a sledge with a 123-ton stone to be 8 cm/s (Materials and Methods). This estimate indicates that the coefficient of kinetic friction should be similar to the static value of 0.2–0.4 according to the experimental results at different temperatures of ref. 15. In addition, the high value of μ indicates that a water film could not be established spontaneously when pulling the sledge with the stone directly on the ice path (Materials and Methods). How, then, could lubricated sliding be accomplished?

We investigated whether a water film could be generated and maintained during transportation by methods other than frictional heating. Here we suggest that a lubricating film of water was created by directly pouring well water on the ice-covered ground to wet the contact surfaces during the movement of the sledge. As the sledge starts moving (SI Materials and Methods), the water poured in front of the sledge would lubricate the sliding surface, as is illustrated in ancient Egyptian bas-reliefs (1). In addition, although the sledge slides on the ice surface at a low speed of 8 cm/s, the value of μ could still be as low as that in the high-speed regime with poured water, because when a film of water is present the coefficient of static friction is very small, ∼0.02, at a temperature close to but still below 0 °C (17). Moreover, the maintenance of a lubricating water film is possible, because water would not completely freeze within 2 min (Materials and Methods), which was the time for the sledge to pass through a fixed point, at a temperature around –3.7 °C in daytime; of course, heated water could be used to delay the freezing. Therefore, we conclude that water supplied from the wells was not only used to create the ice path before the sledge was started to move, but also was poured on the contact surfaces when the sledge was moving to further reduce the friction by generating a lubricating water film.

Conclusion

We have obtained answers to the three questions raised at the beginning: (i) Sliding was more reliable than wheeled vehicles and log rollers for such heavy-load, long-distance transportation; (ii) lubricated wood-on-ice sliding is more efficient than other lubrication methods, and it was feasible according to the weather conditions of Beijing’s winter, which was cold enough to create an artificial ice path while still allowing a water film to exist for lubrication; and (iii) the lubricating water film makes the Chinese case different from the cases in the far northern areas with extremely low temperatures. The transportation of huge stones in 15th- and 16th-century China took full advantage of the natural properties of ice, such as sufficient hardness, flatness, and low friction with a water film, so it provides an early example of ice lubrication, which is a scientific area developed from the middle of the 19th century (18–20) and complements current studies of the high-speed regime relevant to competitive ice sports (16).

Materials and Methods

The Coefficient of Friction μ in Table 1.

The value μ = 0.23 for case 1 is the result estimated by ref. 1, which matched well with the typical value of 0.2 of wet wood-on-wood sliding, so that the typical values of μ for the other cases in the table are estimated with the same method as described in ref. 1 to facilitate comparison. Here μ is estimated with μ = F/mg, where the towing force F = nf was estimated based on the mean traction force of f = 800 N per man and the number of men n, and the gravitational acceleration g ≈ 10 m/s2. Case 4 is an exception, which is discussed in detail below with respect to ice friction of the far north case.

Criteria for a Reasonable Number of Men for Hauling a Sledge.

In Fig. 2, the number of men n is estimated with n = F/f = μmg/f. There were examples of pulling heavy sledges in both ancient bas-reliefs and modern experiments in which a team of up to 300 men were pulling [e.g., 172 men (1) for the ancient Egyptian case 1 in Table 1]. With regard to the 1978 experiments performed with a reproduced fifth-century sledge in Japan (9), a team of 300 men successfully pulled the sledge with a 14-ton stone on a dry riverbed, where at first a team of 200 men was prepared but failed. Three hundred men were thought too many to be acceptable for the transport process, but 36 men were considered reasonable for pulling the 14-ton stone with the aid of log rollers (case 2 in Table 1). In addition, as stated in ref. 1, the requirement for 1,200 men to pull a huge stone is considered impractical for an ancient Egyptian case. Regarding the long distance of 70 km and the long duration of 28 d in the ancient Chinese case, the organization of the masses of men and the efficiency of the total pulling force should also be taken into account. Therefore, we consider a reasonable estimate as n < 300 men, whereas the cases with n > 1,200 men are considered impractical.

Beijing’s Winter Weather Conditions.

According to the documented average temperature of the winter half-year in China during the last 2,000 y, the 15th and 16th centuries were between the warm epoch (570s–1310s) and the cold trough (1650s–1670s), and the fluctuation of the average temperature in this period was within ±0.5 °C of the present value (21, 22). Based on the data in 1971–2000, the average temperature of Beijing in January is –3.7 °C, with an average minimum temperature of –8.4 °C and an average maximum temperature of 1.8 °C. Many lakes in Beijing freeze in winter, and the thickness of the ice cover can be >15 cm; people can skate safely from the end of December through January.

Sliding Speed of the Sledge with a 123-Ton Stone (Case 3 in Table 1).

For calculating the sliding speed U, we need to estimate the time t used first. Although it took 28 d to finish the s = 70-km distance (7), the actual time for the movement is unknown owing to the lack of illumination after sunset in ancient times. We suppose the stone was moving 8.5 h/d based on the typical sunrise and sunset times (0730–1700 hours) in January in Beijing, with 1 h reserved for preparations and auxiliary work. Consequently, we estimate a total transport time of t = 238 h over 28 d. This can be verified by t = μmgs/np = 243 h, with the average power of a man p ≈ phorse/10 = 64 W per man, where the average power of an average draft horse phorse ≈ 0.86 horsepower ≈ 640 W (23). We subsequently obtain U = s/t ≈ 8 cm/s with t ≈ 240 h, and it is in the low-speed regime of ice lubrication.

Ice Friction of Transporting the 123-Ton Stone (Case 3 in Table 1).

This case is in the low-speed regime of ice friction, because U ≈ 8 cm/s. Ice can melt to produce lubricant itself, so the friction mechanism can be complicated. When mixed lubrication exists, the coefficient of friction can have a wide range of values (24). However, when a film of water with a thickness of ∼70 μm was present (17), the coefficient of kinetic friction μ was generally about 0.02–0.03 (15), and even the coefficient of static friction became very small, ∼0.02, at a negative temperature close to 0 °C (17). Consequently, here we suppose that a lubricating water film is established, and then investigate the possibility of maintaining the thin film of h ≈ 70 μm when μ ≈ 0.03. The water-lubricated wood-on-ice sliding is then simplified to an unsteady-state one-dimensional conduction problem with a constant surface temperature T0 = 0 °C (SI Materials and Methods). Supposing the length of the sledge was l = 9.6 m, which is the same as the length of the huge stone, the time for the whole sledge to pass through a fixed point, that is, the contact time, tl = l/U ≈ 120 s. The results of the estimate indicate that the frictional heating is not sufficient to compensate the total heat loss, which includes the heat diffusing into the wood sledge and into the ice surface and the heat melting the ice surface to maintain a water film of 70-μm thickness. Therefore, when pulling the sledge with the stone directly on the ice-covered ground in a low-speed regime at several centimeters per second, an effective lubricating water film may not be established spontaneously. This conclusion is consistent with Bowden’s experimental results in the low-speed regime (15).

Ice Friction of the Far North Case (Case 4 in Table 1).

In the far north case, several sledges loaded with mining equipment of a maximum load m = 28 tons were dragged by a track-type tractor with a crew of four men in a temperature of –55 °C, traveling s = 212.4 km (132 miles) in 10 d in 1934 (13). Assuming that the sledges were moved continuously in the 10 d with the four men driving alternately, we obtain that the time for the sliding t = 240 h and the average speed U of the sledges was U = s/t ≈ 25 cm/s, which is far below the high-speed regime (5 m/s) (15). Regarding the extreme low ambient temperature of –55 °C, a heat transfer model of an unsteady-state one-dimensional problem with a constant heat flux input is applied to the wood-on-ice sliding (SI Materials and Methods). The frictional force F = μmg is considered as the total heat produced per unit displacement (joules per meter) (24), so that the heat produced by F is QF = Fl, where l is the length of the contact area. During the contact time tl = l/U, the heat flux qF = QF/tl = FU at the ice surface generated by the frictional force is considered constant. The results of the estimate indicate that the frictional heating is not sufficient to heat the ice surface to 0 °C, so that no water film will be generated between the sledges and the ice surface; in this case the experimental results of the dry wood-on-ice sliding μ ≈ 0.36 from ref. 15 is used. To verify the value of μ, we calculate the power needed for the transportation P = μmgs/t = 24.8 kW, which could be realized by a common tractor in the early 1930s, such as the Caterpillar Sixty (25) with rating power of 26 kW (35 horsepower) at the drawbar.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Palace Museum (Beijing, China) and photographer Chui Hu for kindly providing the photos of the Forbidden City and the Large Stone Carving, and Mr. Xiaohu Li, Prof. Youbin Chen, and Mr. Bing Dong for helpful discussions. This work is supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China Grants 51275036 and 51275266, and Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities Grant FRF-TP-09-013A.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

*This Direct Submission article had a prearranged editor.

See Commentary on page 19978.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1309319110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Dowson D. History of Tribology. 2nd Ed. London: Professional Engineering Publishing; 1998. pp. 28–45. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Guinness World Records (2004) Heaviest building moved intact. Available at http://www.guinnessworldrecords.com/records-1/heaviest-building-moved-intact/. Accessed October 12, 2013.

- 3.Needham J. Science and Civilization in China, Vol 4: Physics and Physical Technology, Part 2: Mechanical Engineering. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1965. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Barme GR. The Forbidden City. Cambridge, MA: Harvard Univ Press; 2011. pp. 25–46. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wood F. Forbidden City. London: British Museum; 2005. pp. 10–16. [Google Scholar]

- 6. World Heritage Centre (2004) Imperial Palaces of the Ming and Qing Dynasties in Beijing and Shenyang. Available at http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/439. Accessed October 12, 2013.

- 7.He ZS. Liang Gong Ding Jian Ji. Beijing: Zhonghua Book Co; 1985. Vol 1, pp 2, and Vol 2, pp 7–14. Chinese. [Google Scholar]

- 8.National Library of China . Beijing in Ancient Maps. Beijing: Surveying and Mapping Press; 2010. p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Tsuboi U. Observations on Japanese tribological history and representative heritages from ancient to modern times. Tribology Online. 2011;6(3):160–167. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Faulkner CH. Moved buildings: A hidden factor in the archaeology of the built environment. Hist Archaeol. 2004;38(2):55–67. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Carr D. The Cape Hatteras Lighthouse: Sentinel of the Shoals. Rev and Upd Ed. Chapel Hill, NC: The University of North Carolina Press; 2000. pp. 110–138. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Shimotsuma Y, Ogata M, Nakatsuji T, Ozawa Y. History of tribology in ancient northeast Asia – The Japanese sledge and the Chinese Chariot. Tribology Online. 2011;6(3):174–179. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Anonymous Tractor ‟trains” move freight in far north. Popular Mechanics. 1934;62(4):555. [Google Scholar]

- 14. China Central Television (2013) Lao Zhan Zhang Shi Zuo Ping Yi Zhi Xin Jia. Available at http://news.cntv.cn/2013/02/05/ARTI1360022939796560.shtml. Accessed October 12, 2013. Chinese.

- 15.Bowden FP. Friction on snow and ice. Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci. 1953;217(1131):462–478. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kietzig A-M, Hatzikiriakos SG, Englezos P. Physics of ice friction. J Appl Phys. 2010;107(8):081101. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bowden FP, Hughes TP. The mechanism of sliding on ice and snow. Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci. 1939;172(949):280–298. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faraday M. On regelation, and on the conservation of force. Philos Mag. 1859;17(113):162–169. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Thomson J. On recent theories and experiments regarding ice at or near its melting-point. Proc R Soc Lond. 1859;10:151–160. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Reynolds O. Paper on Mechanical and Physical Subjects 2. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 1901. pp. 734–740. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chu KC. A preliminary study on the climatic fluctuations during the last 5,000 years in China. Sci Sin. 1973;16(2):226–256. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ge Q, Zheng J, Hao Z. Temperature variation over the past 2,000 years in China. Bull Chinese Acad Sci. 2009;23(4):232–233. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Forbes RJ. Studies in Ancient Technology. 3rd Ed. Vol 2. Leiden, The Netherlands: E. J. Brill; 1993. pp. 80–88. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Evans DCB, Nye JK, Cheeseman KJ. The kinetic friction of ice. Proc R Soc Lond A Math Phys Sci. 1976;347(1651):493–512. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Orlemann EC. Caterpillar Chronicle: The History of the World’s Greatest Earthmovers. St. Paul, MN: MBI Publishing; 2000. pp. 33–45. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.