Significance

It is widely acknowledged that a projectile impacting a ceramic target may erode on the surface of the target without substantial penetration for a significant amount of time and then suddenly start to penetrate. This phenomenon, commonly referred to as dwell, although known for four decades, remains largely unexplained. We demonstrate that dwell also occurs for a gel-like target material impacted by a water jet due to an increase in the force exerted by the jet on the target. The force increase is a fluid–structure interaction effect and traced to flow reversal of the jet caused by the progressive deformation of the jet–target interface. This effect is expected to occur in situations such as water-jet cutting and needleless injection.

Keywords: impact loading, ballistic penetration, fluid–structure interaction, interface defeat

Abstract

It is widely acknowledged that ceramic armor experiences an unsteady penetration response: an impacting projectile may erode on the surface of a ceramic target without substantial penetration for a significant amount of time and then suddenly start to penetrate the target. Although known for more than four decades, this phenomenon, commonly referred to as dwell, remains largely unexplained. Here, we use scaled analog experiments with a low-speed water jet and a soft, translucent target material to investigate dwell. The transient target response, in terms of depth of penetration and impact force, is captured using a high-speed camera in combination with a piezoelectric force sensor. We observe the phenomenon of dwell using a soft (noncracking) target material. The results show that the penetration rate increases when the flow of the impacting water jet is reversed due to the deformation of the jet–target interface––this reversal is also associated with an increase in the force exerted by the jet on the target. Creep penetration experiments with a constant indentation force did not show an increase in the penetration rate, confirming that flow reversal is the cause of the unsteady penetration rate. Our results suggest that dwell can occur in a ductile noncracking target due to flow reversal. This phenomenon of flow reversal is rather widespread and present in a wide range of impact situations, including water-jet cutting, needleless injection, and deposit removal via a fluid jet.

Ceramic materials, although having a reputation for being inherently brittle, have been used for different armor systems for almost a century. The application of ceramic-based armor ranges from protection of aircraft and personnel against small-caliber threats, to vehicle armor designed to defeat long-rod penetrators and shaped charges.

Here, we consider thick, well-confined ceramic armor systems designed to withstand the high-velocity impact of heavy-metal long-rod penetrators. Such systems are extensively used to study the dynamic penetration properties of ceramics over relatively long time frames: the confinement prevents/reduces the macroscopic cracking of the ceramic target and thus provides a more controlled experimental setting where statistical effects of cracking are minimized.

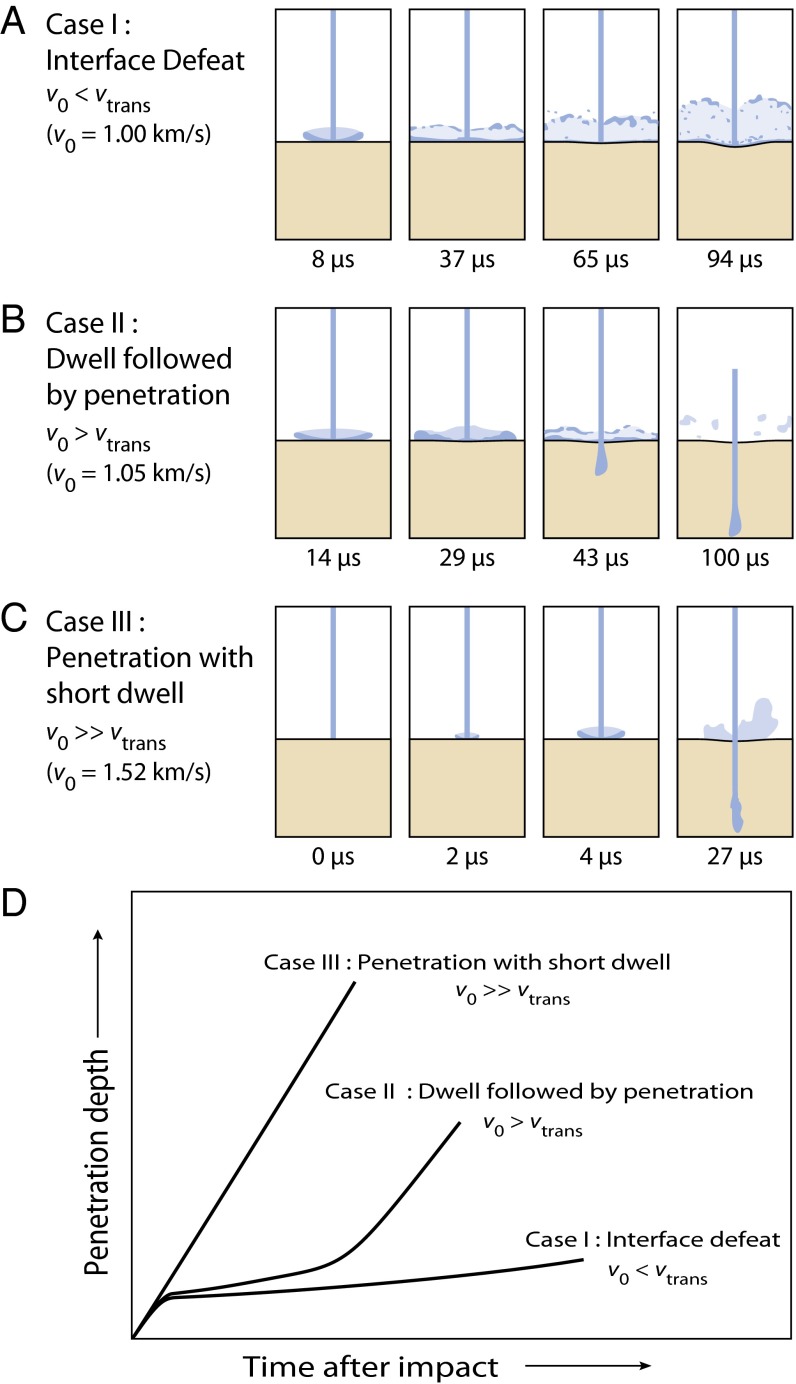

The time-resolved penetration behavior of ceramic armor has been extensively studied over the past 45 y using flash radiography, a technique used for impact experiments involving optically opaque targets (1–4). As sketched in Fig. 1, the typical penetration–time behavior of a ceramic target impacted by a metallic long rod is characterized by three cases depending on the impact velocity  . Case I: Below a critical impact velocity, the metallic long rod erodes completely on the target surface without significant penetration (Fig. 1A). This phenomenon is commonly referred to as interface defeat and the critical transition velocity is labeled “

. Case I: Below a critical impact velocity, the metallic long rod erodes completely on the target surface without significant penetration (Fig. 1A). This phenomenon is commonly referred to as interface defeat and the critical transition velocity is labeled “ .”

.”

Fig. 1.

Sketches illustrating the three regimes of penetration of ceramic targets by long-rod penetrators as a function of projectile impact velocity  . (A) For

. (A) For  , the long-rod projectile is eroded on the target surface without significant penetration. This regime is called “interface defeat.” (B) For

, the long-rod projectile is eroded on the target surface without significant penetration. This regime is called “interface defeat.” (B) For  slightly larger than

slightly larger than  , the projectile dwells on the target surface for at least 29 μs before penetration commencing at a high rate. (C) For

, the projectile dwells on the target surface for at least 29 μs before penetration commencing at a high rate. (C) For  , penetration into the target occurs after a much shorter dwell period. (D) Sketch of typical penetration rate versus time curves for the three cases I–III. (A and B adapted from ref. 10; C adapted from ref. 12.)

, penetration into the target occurs after a much shorter dwell period. (D) Sketch of typical penetration rate versus time curves for the three cases I–III. (A and B adapted from ref. 10; C adapted from ref. 12.)

Case II: For velocities slightly higher than the transition velocity, a phase of projectile defeat followed by penetration can be observed (Fig. 1B). The phase without penetration has been termed dwell because the penetrator “dwells” on the target surface for a duration called dwell time. Case III: As the impact velocity increases well beyond the transition velocity, dwell times decrease until they become too short to be measured (Fig. 1C) (5).

The most widely used explanation for the phenomenon of dwell is cracking-induced loss of penetration resistance of the target material. This explanation is mainly based on postmortem examination of recovered targets (6, 7). A region of intense microcracking and cone cracks immediately under the impact site was observed in cross-sections of ceramic targets subjected to impacts just below the transition velocity. Consequently, it is hypothesized that dwell occurs during the time when the ceramic transitions from an intact to a damaged state (5, 8).

However, three critical failings of this hypothesis can be identified. First, whereas microcracking (comminution) was observed in silicon carbide (SiC), no comminution occurred in tungsten carbide (WC) and boron carbide (B4C) targets, even though they display the phenomenon of dwell. Second, the process of cracking takes place on a timescale of the order of 1 μs (9), whereas dwell times can be up to two orders of magnitude higher (10, 11). Finally, there is experimental evidence that the penetration rate during dwell is not zero, indicating that the target material is pushed away or removed already during dwell (12). To conclude, the cracking-induced loss of penetration resistance of the target does not provide a satisfactory explanation for the origins of dwell.

In search for an alternative explanation, we note that Renström et al. (13) demonstrated that the loading from the impacting long rod on the ceramic targets is predominantly inertial (or hydrodynamic) in nature. This raises the question of whether fluid–structure interaction (FSI) between the fluid-like projectile and the deformable target might offer another possible explanation for the dwell phenomenon. FSI effects have been studied in the context of sand sprays impacting deformable structures (14, 15). Similar to the impacting long rod, the loading by the sand is also primarily inertial in nature. In such cases there is a substantial increase in the momentum transmitted by the sand to a deformable structure compared with sand impact on a rigid structure.

In the ceramic target experiments with which we are concerned, the eroding projectile seems to exhibit a flow alteration due to the deformation of the target surface (Fig. 1). This flow alteration is also observed in numerical simulations of related experiments (16). The situation closely resembles a water jet hitting a dimpled rigid surface as shown in Fig. 2, a textbook example from which we know that the transmitted momentum and the impact force increase with increasing curvature of the surface (17). Considering the rate of momentum of the fluid striking the target surface and the fluid leaving the target surface, the force  exerted on the target by the jet (in the direction of the incoming jet) is given by

exerted on the target by the jet (in the direction of the incoming jet) is given by

where  is the angle between incoming and exiting fluid,

is the angle between incoming and exiting fluid,  is the material density of the jet, and

is the material density of the jet, and  the cross-sectional area of the jet. This simple expression can be used to gauge what phenomenon might occur when a jet impacts a deforming target (for cases when the jet velocity is much larger than the penetration rate). With increasing deformation of the surface of the target,

the cross-sectional area of the jet. This simple expression can be used to gauge what phenomenon might occur when a jet impacts a deforming target (for cases when the jet velocity is much larger than the penetration rate). With increasing deformation of the surface of the target,  decreases, resulting in an increase in the force

decreases, resulting in an increase in the force  ––it is this FSI effect that we hypothesize results in the unsteady penetration rate of the target. Numerical simulations, such as those in ref. 16, suggest that the impact pressure is affected by the penetration–deformation of the target surface, but they show no clear correlation between the impact pressure variations and the associated penetration rates.

––it is this FSI effect that we hypothesize results in the unsteady penetration rate of the target. Numerical simulations, such as those in ref. 16, suggest that the impact pressure is affected by the penetration–deformation of the target surface, but they show no clear correlation between the impact pressure variations and the associated penetration rates.

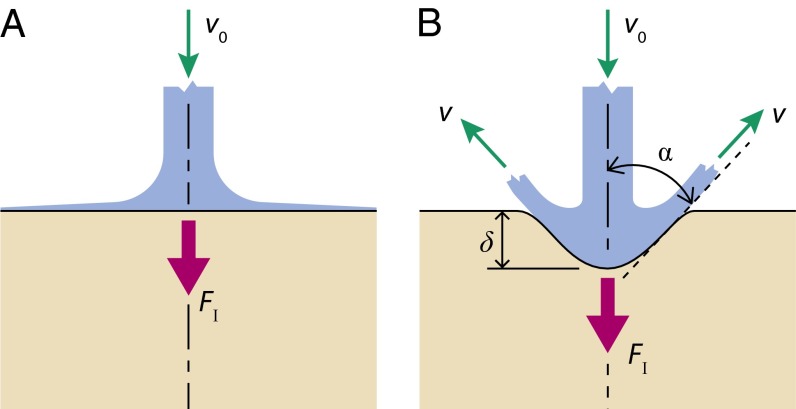

Fig. 2.

Schematic view of the proposed FSI mechanism resulting in an unsteady penetration rate due to the impact of a fluid jet with velocity  . (A) During the initial stages of the jet impact, the target surface is flat and the fluid spreads horizontally. (B) As the jet deforms the target and penetrates at depth δ, it creates a dimple at the impact site; the flow pattern changes, resulting in backflow of the fluid with a velocity

. (A) During the initial stages of the jet impact, the target surface is flat and the fluid spreads horizontally. (B) As the jet deforms the target and penetrates at depth δ, it creates a dimple at the impact site; the flow pattern changes, resulting in backflow of the fluid with a velocity and a consequent increase in the impact force

and a consequent increase in the impact force  , which increases as the jet exit angle

, which increases as the jet exit angle  decreases.

decreases.

This study aims to explore the FSI during projectile impact by using scaled analog experiments. These are designed to circumvent the two major challenges associated with the previously described ceramic target experiments, namely: (i) to obtain direct impact force measurements, and (ii) to achieve a sufficient spatial and temporal resolution of the 3D problem with a very limited number of 2D images. We therefore perform experiments wherein a low-velocity water jet impacts on a translucent gel.

We show that our scaled analog experiments reproduce the penetration versus time responses observed for ceramic targets impacted by long-rod penetrators, albeit at much lower impact velocities and consequent penetration rates. Results presented here include three impact velocities: slightly lower, slightly higher, and significantly higher than the transition velocity  . Similar to the ceramic target experiments, the loading times in our scaled experiments are much longer than the time for elastic wave propagation through the target. This implies that on the timescale of the loading, the target is in static equilibrium insomuch as the force exerted by the jet on the target is equal to the reaction force between the target and the support structure. Thus, to quantify the FSI effect we perform direct impact force measurements by placing the translucent gel target on a high-sensitivity piezoelectric force sensor. The force

. Similar to the ceramic target experiments, the loading times in our scaled experiments are much longer than the time for elastic wave propagation through the target. This implies that on the timescale of the loading, the target is in static equilibrium insomuch as the force exerted by the jet on the target is equal to the reaction force between the target and the support structure. Thus, to quantify the FSI effect we perform direct impact force measurements by placing the translucent gel target on a high-sensitivity piezoelectric force sensor. The force  measured by the transducer is equal to the impact force. We present these measurements in terms of a nominal impact pressure

measured by the transducer is equal to the impact force. We present these measurements in terms of a nominal impact pressure  defined as

defined as

where  is the cross-sectional area of the incoming jet.

is the cross-sectional area of the incoming jet.

We also perform a series of control creep penetration experiments wherein the penetration force is kept constant by applying a fixed load  on a steel-rod penetrator with cross-sectional area

on a steel-rod penetrator with cross-sectional area  , i.e., equal to that of the water jet. The control experiments are designed such that the penetration pressure

, i.e., equal to that of the water jet. The control experiments are designed such that the penetration pressure  is equal to that exerted by the water jet on a rigid flat target:

is equal to that exerted by the water jet on a rigid flat target:

The contrast between the water-jet penetration versus time responses and those in the control creep experiments will serve to demonstrate that it is the FSI effect that results in the observed unsteady penetration response.

Results

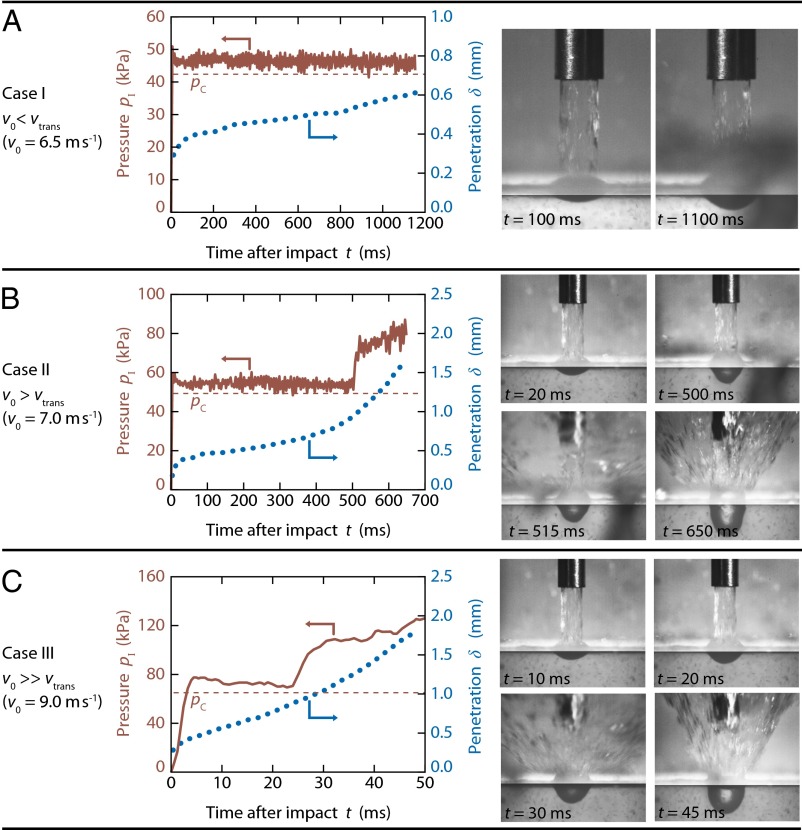

Fig. 3 summarizes the results from water-jet impact experiments using a 2-mm-diameter water jet and demonstrates that scaled analog experiments qualitatively reproduce the long-rod penetration response of ceramic targets. On the right-hand side of Fig. 3, selected frames from digital high-speed imaging illustrate the impact event. On the left-hand side, penetration–time and impact-pressure–time plots are shown for three jet velocities  , with time

, with time  corresponding to the instant of first impact of the jet against the target. Based on these jet velocities, three different target responses can be distinguished, which we denote as cases I, II, and III.

corresponding to the instant of first impact of the jet against the target. Based on these jet velocities, three different target responses can be distinguished, which we denote as cases I, II, and III.

Fig. 3.

Experimental results from water-jet impact (Ø2 mm) on a soft, translucent target (high-vacuum grease) highlighting the three types of penetration response depending on the jet velocity  . (Left) Plots of the measured impact pressure versus time (solid line) and penetration versus time (dotted curve) curves, with time

. (Left) Plots of the measured impact pressure versus time (solid line) and penetration versus time (dotted curve) curves, with time  corresponding to the instant that the jet first impacts the target. The dashed horizontal line indicates the pressure

corresponding to the instant that the jet first impacts the target. The dashed horizontal line indicates the pressure  for the normal impact of the water jet against a flat surface. (Right) High-speed images of the impact event at selected times. (A) Case I: For a jet impact velocity of

for the normal impact of the water jet against a flat surface. (Right) High-speed images of the impact event at selected times. (A) Case I: For a jet impact velocity of  , the jet flows radially outward on the surface of the target throughout the experiment. The impact pressure remains constant whereas the penetration continues at a slow but steady rate. (B) Case II: For a jet impact velocity of

, the jet flows radially outward on the surface of the target throughout the experiment. The impact pressure remains constant whereas the penetration continues at a slow but steady rate. (B) Case II: For a jet impact velocity of  , the penetration rate increases sharply at

, the penetration rate increases sharply at  coinciding with a sudden increase in the impact pressure and the onset of the backflow of the jet. The response before

coinciding with a sudden increase in the impact pressure and the onset of the backflow of the jet. The response before  , when the jet spreads horizontally on the target surface, may be viewed as the dwell phase. (C) Case III: Measurements and observations closely resemble those of case II but with no discernible dwell phase.

, when the jet spreads horizontally on the target surface, may be viewed as the dwell phase. (C) Case III: Measurements and observations closely resemble those of case II but with no discernible dwell phase.

Case I: For a jet velocity of  the instantaneous elastic deformation of the target material is followed by a constant penetration rate, as indicated by the dotted line in Fig. 3A. Further, the nominal impact pressure

the instantaneous elastic deformation of the target material is followed by a constant penetration rate, as indicated by the dotted line in Fig. 3A. Further, the nominal impact pressure  remains constant throughout the experiment and is approximately equal to the nominal pressure applied by a jet normally impinging on a flat rigid surface. This pressure is given by

remains constant throughout the experiment and is approximately equal to the nominal pressure applied by a jet normally impinging on a flat rigid surface. This pressure is given by  (Eq. 3) with

(Eq. 3) with  and indicated by the dashed line in Fig. 3A. Note that the water jet spreads out laterally over the target surface during the entire experiment, as shown on the right-hand side of Fig. 3A and in Movie S1.

and indicated by the dashed line in Fig. 3A. Note that the water jet spreads out laterally over the target surface during the entire experiment, as shown on the right-hand side of Fig. 3A and in Movie S1.

Case II: In contrast with case I, for a slightly higher impact velocity of  , the initial elastic penetration is followed by slow penetration until a penetration depth equal to approximately half the jet diameter is reached at about

, the initial elastic penetration is followed by slow penetration until a penetration depth equal to approximately half the jet diameter is reached at about  , where

, where  corresponds to the instant that the jet first impacts the target. Thereafter, the penetration rate increases rapidly (Fig. 3B). This is reminiscent of the phenomenon of dwell followed by penetration as sketched in Fig. 1 for a ceramic target impacted by a long-rod penetrator. Intriguingly, the impact pressure

corresponds to the instant that the jet first impacts the target. Thereafter, the penetration rate increases rapidly (Fig. 3B). This is reminiscent of the phenomenon of dwell followed by penetration as sketched in Fig. 1 for a ceramic target impacted by a long-rod penetrator. Intriguingly, the impact pressure  , which was almost constant after impact at a value equal to

, which was almost constant after impact at a value equal to  , also rises abruptly at

, also rises abruptly at  . The high-speed images in Fig. 3B, taken at t = 500 and

. The high-speed images in Fig. 3B, taken at t = 500 and  , establish the correlation between this abrupt increase in

, establish the correlation between this abrupt increase in  and the associated change in flow direction of the water jet (see also Movie S2). We shall refer to this flow pattern as backflow. This change in the flow pattern has geometrical origins, which is understood as follows. The jet creates a dimple at the impact site that grows as the target deformation proceeds, which then forces the angle

and the associated change in flow direction of the water jet (see also Movie S2). We shall refer to this flow pattern as backflow. This change in the flow pattern has geometrical origins, which is understood as follows. The jet creates a dimple at the impact site that grows as the target deformation proceeds, which then forces the angle  at which the water leaves the target surface to decrease. This results in an increase of the momentum flux (force) from the jet to the target. Given the temporal correlation between the increase in the penetration rate and the increase in impact pressure, we argue that the increase in impact pressure is the cause of the increase in penetration rate.

at which the water leaves the target surface to decrease. This results in an increase of the momentum flux (force) from the jet to the target. Given the temporal correlation between the increase in the penetration rate and the increase in impact pressure, we argue that the increase in impact pressure is the cause of the increase in penetration rate.

Case III: At an impact velocity of  , the initial period of lower penetration rate is almost indistinguishable from the period of accelerated penetration rate (Fig. 3C and Movie S3). The abrupt increase in impact pressure at

, the initial period of lower penetration rate is almost indistinguishable from the period of accelerated penetration rate (Fig. 3C and Movie S3). The abrupt increase in impact pressure at  is again associated with the formation of backflow, as seen in the high-speed images in Fig. 3C at t = 20 and

is again associated with the formation of backflow, as seen in the high-speed images in Fig. 3C at t = 20 and  . We note in passing that the timescales in case III are approximately an order of magnitude smaller than those in case II.

. We note in passing that the timescales in case III are approximately an order of magnitude smaller than those in case II.

These three cases strongly resemble the three types of target response reported for ceramic armor materials, namely interface defeat, dwell followed by penetration, and penetration with no discernible dwell (compare the sketches of the penetration–time traces in Fig. 1 with the measurements in Fig. 3). Consequently, an alternative explanation for the dwell phenomenon seems to exist, wherein dwell is purely a result of an FSI effect resulting from geometrical changes in the target. This assertion, of course, assumes that the observed increases in penetration rate are not a result of a material softening (or damage) of the gel due to the penetration.

Increases in Penetration Rate Are a Result of FSI Effects Rather than Material Softening.

To further substantiate the hypothesis that the increases in penetration rate are due to an FSI effect and not material damage or softening, we conducted creep penetration experiments with a cylindrical, flat-bottomed penetrator at penetration pressures  (Eq. 3) corresponding to the jet velocities

(Eq. 3) corresponding to the jet velocities  , 7, and

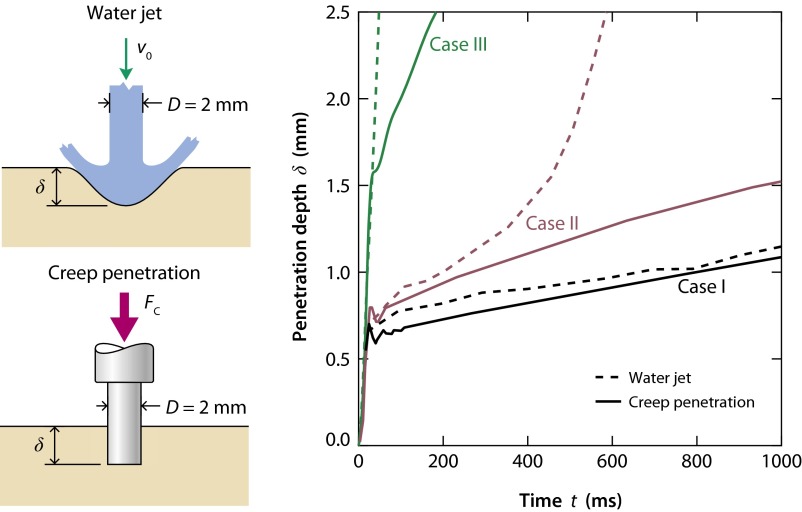

, 7, and  (i.e., cases I, II, and III above). To make direct comparisons, Fig. 4 displays penetration versus time curves from both experiments for these three cases.

(i.e., cases I, II, and III above). To make direct comparisons, Fig. 4 displays penetration versus time curves from both experiments for these three cases.

Fig. 4.

Comparison between the penetration versus time responses for the jet impact and control creep penetration experiments. Results are shown for the three cases presented in Fig. 3. The equivalence between jet impact and creep penetration experiments is given by Eq. 3 such that the penetration pressure applied in the creep experiments is given by  , where

, where  is the jet velocity. In case I, the two experiments give very similar penetration responses. By contrast, in case II, the penetration rate in the creep experiments remains steady whereas there is a sharp increase in the penetration rate in the jet impact experiments corresponding to the onset of backflow. In case III, backflow sets in early in the penetration history. Immediately after the initial elastic penetration, the penetration rate is higher in the jet impact experiments compared with the creep experiments.

is the jet velocity. In case I, the two experiments give very similar penetration responses. By contrast, in case II, the penetration rate in the creep experiments remains steady whereas there is a sharp increase in the penetration rate in the jet impact experiments corresponding to the onset of backflow. In case III, backflow sets in early in the penetration history. Immediately after the initial elastic penetration, the penetration rate is higher in the jet impact experiments compared with the creep experiments.

In general, our creep experiments generated penetration versus time curves similar to conventional creep indentation tests. On the abrupt application of the load, the penetration almost instantaneously reaches a certain value, which is attributable to the elastic response of the material. This is followed by a second stage with an approximately linear relation between penetration and elapsed time––this regime can be directly correlated with the steady-state creep response of the gel (18).

Now consider each of the three cases shown in Fig. 4 in turn. In case I, a penetration pressure  (given by Eq. 3 with

(given by Eq. 3 with  ) was applied and the creep penetration rate strongly correlates with the penetration rates observed in the jet impact experiment. This is consistent with our expectations as no backflow occurred in the jet impact at

) was applied and the creep penetration rate strongly correlates with the penetration rates observed in the jet impact experiment. This is consistent with our expectations as no backflow occurred in the jet impact at  and hence the two loading scenarios are equivalent.

and hence the two loading scenarios are equivalent.

Next, consider case II with a penetration pressure  . The penetration responses in both the jet impact and creep experiment are almost identical until a loading time

. The penetration responses in both the jet impact and creep experiment are almost identical until a loading time  . By this stage, the penetration is equal to approximately half the diameter of the water jet or penetrator. Backflow commences in the jet impact experiment, which increases the penetration rate as argued above. However, in the control creep experiment there is no increase in the penetration load and the penetration continues at a steady rate. This confirms that it is change of the loading in the jet impact experiment (i.e., FSI) that causes the unsteady penetration rather than material softening.

. By this stage, the penetration is equal to approximately half the diameter of the water jet or penetrator. Backflow commences in the jet impact experiment, which increases the penetration rate as argued above. However, in the control creep experiment there is no increase in the penetration load and the penetration continues at a steady rate. This confirms that it is change of the loading in the jet impact experiment (i.e., FSI) that causes the unsteady penetration rather than material softening.

In case III with a penetration pressure  , the penetration rates of jet impact and creep experiment coincide only up to the limit of elastic deformation. Thereafter, the penetration rates in the creep experiment are lower than the jet impact experiment. We rationalize this by noting that elastic deformation in this high-pressure case causes a penetration greater than half the jet diameter and, therefore, backflow commences immediately resulting in an increase in the penetration force in the jet impact experiment compared with the constant force in the creep experiment.

, the penetration rates of jet impact and creep experiment coincide only up to the limit of elastic deformation. Thereafter, the penetration rates in the creep experiment are lower than the jet impact experiment. We rationalize this by noting that elastic deformation in this high-pressure case causes a penetration greater than half the jet diameter and, therefore, backflow commences immediately resulting in an increase in the penetration force in the jet impact experiment compared with the constant force in the creep experiment.

In summary, our results demonstrate that the unsteady penetration response observed in the jet impact experiments is due to an FSI effect in which the force exerted on the target increases as progressive deformation of the target causes backflow of the jet.

Discussion

In the results presented above, we have demonstrated that unsteady penetration can occur due to backflow of the impacting jet rather than any associated softening or damage of the target material. However, there is widespread acknowledgment in the literature (19, 20) that the unsteady penetration observed in ceramic targets is related to damage accumulation within the ceramic. We rationalize these seemingly contrasting mechanisms as follows. Damage and backflow are not necessarily mutually exclusive. The impacting jet needs to penetrate to a depth of approximately half the jet diameter before backflow can be established, as sketched in Fig. 2. Unlike the vacuum grease target used here, brittle ceramic targets would inevitably experience damage accumulation at this level of penetration. The backflow that is associated with the formation of the cavity will then result in an amplification of the penetration rate as argued above. As a corollary, the mechanism by which the initial cavity forms is an important factor in controlling the penetration rate. If damage accumulation is the mechanism by which the cavity is formed––as usually found in brittle ceramics––then system design parameters (such as the confinement system, target architecture, etc.) will have a strong effect on the penetration rate (21).

Concluding Remarks

Traditionally, dwell and unsteady penetration is thought of as a phenomenon only present during high-velocity impact of heavy-metal long-rod projectiles against ceramic targets. The common explanation for the end of dwell is thought to be the onset of cracking or damage in the ceramic. However, we make observations of dwell and penetration rates reminiscent of those observed in ceramic target experiments with a scaled system comprising a water jet loading a ductile gel. We demonstrate that in our experiments the observed dwell and unsteady penetration is a result of an FSI effect in which deformation of the target causes backflow of the jet, which then increases the force exerted on the target and thereby the penetration rate. The implication is that the unsteady penetration of brittle ceramic targets might also be related to such an FSI effect: numerical modeling, as pioneered in ref. 16, will help quantify the relative efficacies of damage and FSI in causing the observed unsteady penetration responses of different targets.

One of the limitations of using scaled analog experiments is that the timescales in these experiments are associated with the rate dependence of the gel material, whereas those in the ceramic target experiments are mainly due to material inertia. However, these scaled analog experiments allow better visualization and measurement of the penetration force, which would be impractical in standard ballistic tests.

Finally, we note that the mechanism for unsteady penetration proposed here is an FSI effect that will occur in any system wherein a jet loads a deformable target. Such scenarios are quite common and examples include needleless injection, water-jet cutting, and loading of structures by high-velocity granular sprays.

Materials and Methods

Target Geometry and Preparation.

The cuboidal targets of edge length 20 mm comprised high-vacuum grease (Dow Corning). A mold made of four glass slides was used to punch out the specimens from the as-received bulk grease. Excess material at the two open ends was scraped off using a razor blade and the target capped at one end with a fifth glass slide. The glass slides served as the confinement system for the target. The target was allowed to rest for 48 h before testing. This method of target preparation ensured that voids were not introduced into the grease during the preparation process. We note that both the water jet and penetrator had a diameter of 2 mm; additional tests performed on 30- and 40-mm targets confirmed that the target size was large enough to not influence the results reported here.

Water-Jet Impact Experiments.

The water jet of diameter 2 mm was generated by pushing a plunger into a brass tube using a servo-hydraulic load frame. The penetration process was recorded using a digital high-speed camera (Phantom v12, Vision Research) equipped with a macro lens (Makro-Killar 2.8/90) and a matched multiplier (Vivitar 2×). Two halogen lamps (1000 W) were used for illumination, one positioned behind the target for light that passes through the target and one in front of the target for light that reflects from the target (Fig. S1). The penetration depth was determined from the camera pictures using Phantom software. The accuracy in the measurement of the penetration depth was within ±0.05 mm. The impact force of the jet was measured using an ICP dynamic force sensor (209C12, PCB Piezotronics).

Creep Penetration Experiments.

For creep penetration experiments a custom-made apparatus with a flat-bottomed cylindrical steel penetrator of 2.0-mm diameter was used (Fig. S2). The experimental setup comprises a vertical shaft with the penetrator at the bottom and a circular plate at the top, which supports the dead weight (Fig. S2). By using a spring-loaded mechanism, the penetrator was released and impressed into the sample surface under a constant load. Penetrations were carried out at loads  ranging from 124 to 237 mN, which equate to penetration pressures

ranging from 124 to 237 mN, which equate to penetration pressures  in the range 42 to 81 kPa. The displacement of the penetrator was recorded using the digital high-speed camera. A visco-plastic constitutive law for the target material has been deduced from the creep data (Figs. S3–S5). In terms of the uniaxial strain rate

in the range 42 to 81 kPa. The displacement of the penetrator was recorded using the digital high-speed camera. A visco-plastic constitutive law for the target material has been deduced from the creep data (Figs. S3–S5). In terms of the uniaxial strain rate  as well as the corresponding applied uniaxial stress

as well as the corresponding applied uniaxial stress  and stress rate

and stress rate  , the constitutive relationship is

, the constitutive relationship is

where  is Young’s modulus,

is Young’s modulus,  is the creep rate at the reference stress of

is the creep rate at the reference stress of  , and

, and  is the rate sensitivity exponent. A summary of all creep indentation results and a detailed derivation of the proposed constitutive relationship are provided in SI Text.

is the rate sensitivity exponent. A summary of all creep indentation results and a detailed derivation of the proposed constitutive relationship are provided in SI Text.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

The authors are indebted to the late A. G. Evans (University of California, Santa Barbara) for the many stimulating discussions that helped form the ideas behind this work. The work was supported by the Office of Naval Research Grant N00014-09-1-0573.

Footnotes

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

This article is a PNAS Direct Submission.

This article contains supporting information online at www.pnas.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.1073/pnas.1315130110/-/DCSupplemental.

References

- 1.Wilkins M. 1967. Second progress report of light armor program, Report UCRL-50349 (Lawrence Livermore Lab, Livermore, CA)

- 2.Hauver G-E, Rapacki E-J, Netherwood P-H, Benck R-F. 2005. Interface defeat of long-rod projectiles by ceramic armor. US Army Research Laboratory Report ARL-TR-3590 (Aberdeen Proving Ground, MD)

- 3.Lundberg P, Lundberg B. Transition between interface defeat and penetration for tungsten projectiles and four silicon carbide materials. Int J Impact Eng. 2005;31(7):781–792. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Anderson C-E, Holmquist T-J, Orphal D-L, Behner T. Dwell and interface defeat on borosilicate glass. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2010;7(6):776–786. [Google Scholar]

- 5.LaSalvia J-C, Campbell J, Swab J-J, McCauley J-W. Beyond hardness: Ceramics and ceramic-based composites for protection. JOM. 2010;62(1):16–23. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shockey D-A, et al. Failure phenomenology of confined ceramic targets and impacting rods. Int J Impact Eng. 1990;9(3):263–275. [Google Scholar]

- 7.LaSalvia J-C, McCauley J-W. Inelastic deformation mechanisms and damage in structural ceramics subjected to high-velocity impact. Int J Appl Ceram Technol. 2010;7(5):595–605. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Holmquist T-J, Johnson G-R. The failed strength of ceramics subjected to high-velocity impact. J Appl Phys. 2008;104(1):013533-1–013533-11. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bourne N-K. On kinetics of failure in, and resistance to penetration of metals and ceramics. Adv Appl Ceramics. 2010;109(8):480–486. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Andersson O, Lundberg P, Renstrom R. 2007. Influence of confinement on the transition velocity of silicon carbide. Proceedings of the 23rd International Symposium on Ballistics, eds Gálvez F, Sánchez-Gálvez V, pp 1273–1280.

- 11.Lundberg P, Renström R, Holmberg L. 2001. An experimental investigation of interface defeat at extended interaction time. Proceedings of the 19th International Symposium on Ballistics, ed Crewther IR, pp 1463–1469.

- 12.Behner T, et al. Penetration dynamics and interface defeat capability of silicon carbide against long rod impact. Int J Impact Eng. 2011;38(6):419–425. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Renström R, Lundberg P, Lundberg B. Stationary contact between a cylindrical metallic projectile and a flat target surface under conditions of dwell. Int J Impact Eng. 2004;30(10):1265–1282. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wadley H-N, et al. Deformation and fracture of impulsively loaded sandwich panels. J Mech Phys Solids. 2013;61(2):674–699. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu T, Fleck N-A, Wadley H-N-G, Deshpande V-S. The impact of sand slugs against beams and plates: Coupled discrete particle/finite element simulations. J Mech Phys Solids. 2013;61(8):1798–1821. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Gailly B-A, Espinosa H-D. Modelling of failure mode transition in ballistic penetration with a continuum model describing microcracking and flow of pulverized media. Int J Numer Methods Eng. 2002;54(3):365–398. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Reddy J-N. An Introduction to Continuum Mechanics. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge Univ Press; 2008. pp. 155–156. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bower A-F, Fleck N-A, Needleman A, Ogbonna N. Indentation of a power law creeping solid. Proc R Soc London, Ser A. 1993;441(1911):97–124. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lundberg P, Rentström R, Andersson O (2013) Influence of length scale on the transition from interface defeat to penetration in unconfined ceramic targets. J Appl Mech (80):031804-1–031804-9. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Holmquist T-J, Anderson C-E, Behner T, Orphal D-L. Mechanics of dwell and post-dwell penetration. Adv Appl Ceramics. 2010;109(8):467–479. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Espinosa H-D, Brar N-S, Yuan G, Xu Y, Arrieta V. Enhanced ballistic performance of confined multi-layered ceramic targets against long rod penetrators through interface defeat. Int J Solids Struct. 2000;37:4893–4913. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.