Abstract

Objectives:

Although many have examined the linkages between smoking behaviors across 2 generations, few have examined these linkages among 3 generations.

Methods:

U.S. population representative data for 3 generations are drawn from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID) in order to examine whether smoking behaviors are passed down from generation to generation and the magnitude of the influence of smoking behaviors across generations (N = 830).

Results:

Results indicate direct linkages between both grandparent (G1) and parent (G2) smoking (OR = 4.53; 95% CI = 2.57–7.97) and parent (G2) and young adult offspring (G3) smoking (OR = 2.91; 95% CI = 1.60–5.31). Although the direct link between grandparent (G1) and grandchildren (G3) was not significant (OR = 2.25; 95% CI = 0.96–5.23, p < .10), mediation analyses reveal that the link between G3 and G1 smoking is significantly mediated by G2 smoking.

Conclusions:

Regardless of generation, parent smoking behavior has a direct influence on offspring smoking behavior. The link between grandparent (G1) and grandchild (G3) smoking is mediated by parent (G2) smoking, suggesting that smoking behavior is passed from one generation to the next generation and in turn to the next generation.

INTRODUCTION

Tobacco use remains the “single most preventable cause of disease, disability, and death” in the United States (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011). Despite this, 46.6 million U.S. adults smoke, and nearly all of them will have begun to use tobacco during adolescence or young adulthood (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2012). This can be attributed in part to the greater likelihood of engaging in risky behaviors (such as smoking), during adolescence and young adulthood, and in part to the addictive nature of nicotine, the effect of which is more severe the earlier a person begins smoking (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 1994). It is during young adulthood when occasional smokers generally transition to regular smokers, setting up individuals for lifelong dependency with often devastating health consequences (Benowitz, 2010; Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2011; Ling & Glantz, 2002).

Many of the risk factors associated with young adult smoking are well established, particularly the influence of parental smoking. Strong evidence suggests that parental smoking behaviors are associated with the tobacco use of offspring (Avenevoli & Merikangas, 2003; Jackson, Henriksen, Dickinson, & Levine, 1997; Wilkinson, Shete, & Prokhorov, 2008). An association between parent and child smoking behavior has been reported regardless of whether parents are current or ever-smokers (Gohlmann, Schmidt, & Tauchmann, 2010; Melchior, Chastang, Mackinnon, Galera, & Fombonne, 2010). Although research suggests that offspring with two smoking parents are at the greatest risk of becoming smokers, having even a single smoking parent significantly increases the risk of smoking (Bantle & Haisken De-New, 2002; Gilman et al., 2009; Leonardi-Bee, Jere, & Britton, 2011). There is even some evidence that having a parent who is a past smoker increases the likelihood of smoking among offspring (Bantle & Haisken De-New, 2002). In general, however, studies seem to suggest that offspring are more likely to mimic both smoking and quitting behaviors of their parents (Bricker et al., 2009; den Exter Blokland, Engels, Hale, Meeus, & Willemsen, 2004; Kong, Camenga, Krishnan-Sarin, 2012).

Knowing that parental smoking behavior is strongly related to smoking behavior in offspring, and that this link comprises both genetic and environmental influences, it seems reasonable to assume that this generational link will replicate across multiple generations. Indeed, the large body of literature examining linkages between smoking behaviors in parents and offspring generally assumes this is so. However, the transfer of smoking behavior across three generations has remained largely unexamined (Avenevoli & Merikangas, 2003; Bantle & Haisken De-New, 2002; Gohlmann et al., 2010; Jackson et al., 1997; Melchior et al., 2010; Wilkinson et al., 2008). Thus, the general conviction that the transmission of smoking behavior replicates across generations has yet to be supported by empirical evidence. Moreover, we know little about the nature of this transmission, such as whether smoking behavior is passed directly from one generation to another, including from more distal older generations (i.e., grandparents) to younger generations (i.e., offspring), or whether the link between more distal generations is mediated by proximal generations (i.e., by parental smoking).

For this reason, this study examines the intergenerational transmission of smoking behavior across three generations—from grandparents (G1) to parents (G2) to their adult children (G3)—using uniquely appropriate long-term longitudinal intergenerational data from a U.S. population representative sample spanning more than 40 years (1968–2011). We address the following research questions: (a) Are there direct links between G1 and G2 smoking; G2 and G3 smoking, and G1 and G3 smoking, respectively? and (b) Is the pathway from G1 to G3 smoking mediated by G2 smoking? That is, is smoking behavior transferred from grandparents (G1) to parents (G2) to young adults (G3)?

METHODS

Sample

Intergenerational data representing three generations were drawn from the Panel Study of Income Dynamics (PSID), and the related Child Development Supplement (CDS) and Transition to Adulthood (TA) surveys. The PSID is an ongoing longitudinal survey of a representative sample of U.S. individuals and the family units in which they reside begun in 1968, conducted annually until 1997, and biannually thereafter. Reinterview response rates with PSID participants have been high, ranging between 96% and 98% (McGonagle & Schoeni, 2006). The genealogical design of the PSID—whereby descendants of original sample members become PISD interviewees when they begin their own households—has produced intergenerational data that include information on up to three generations within a family.

In 1997, data from up to two siblings aged 0–12 of PSID families were collected in the first wave of the CDS to the PSID. Three waves of longitudinal CDS data are available, 1997 (CDS-I), 2002 (CDS-II), and 2007 (CDS-III). CDS participants who turn 18 years of age automatically become participants in the TA study. TA participants have been followed repeatedly in 2005, 2007, 2009, and 2011. By 2011, the TA surveys included 1,909 young adults of 18–27-year old, for an overall response rate of 87%. Together, the data available in the PSID/CDS/TA surveys provide a rich and comprehensive set of measures of health behaviors and outcomes, including tobacco use.

Because our focus is on young adult (G3) smoking behaviors, participants in TA 2011 formed the basis for our sample. Of these, 830 had complete data on outcomes and covariates, including data on the smoking behavior of at least one parent and one grandparent. Sample weights were recalibrated for the subsample used here, so that the weighted data remain population representative (Groves et al., 2004). The weighted racial/ethnic composition of the sample used in this study is 74% White, 13% Black, 11% Hispanic or Latino, 1% Asian, 1% Native American or Pacific Islander.

Measures

Young Adult Current Smoking (G3)

In TA 2011, young adults were asked, “Do you smoke cigarettes?” (Yes = 1, No = 0).

Parent (G2) and Grandparent (G3) Current and Ever-Smoking

Data on cigarette smoking from parents and grandparents of the young adults in this study were collected in 1968, 1969, 1970, 1986, 1999, 2001, 2003, 2005, 2007, and 2009. In 1968–1970, respondents were asked, “Is there anyone in the household who smokes cigarettes?” In all other years, respondents were asked, “Do you smoke cigarettes?” and, “Did you ever smoke cigarettes?”

In order to capture whether young adults had a parent (G2) or a grandparent (G1) who had ever smoked, we relied on the combination of responses to these questions with identifiers of whether the respondent was a parent or grandparent of the young adults in our sample. If G1 or G2 respondents answered yes to either being a current smoker or a former smoker across any measurement year, they were categorized as an “Ever-smoker” (coded 1). If G1 or G2 respondents answered no to being a current and former smokers across all measurement years, they were categorized as a “Never-smoker” (coded 0). “Current smokers” included G1 or G2 respondents who indicated they smoked cigarettes (1 = Yes, 0 = No) in the most recent available wave of PSID data (2009).

Covariates

In all analyses, we controlled for a variety of influences known to influence smoking behavior. These included: young adult age, gender (1 = female, 0 = male), race/ethnicity, perceived smoking status of friends during adolescence, income-to-needs ratio, and education. Race/ethnicity was first examined as a collection of five dummy variables dummied out to reflect White as the reference group (1. Black vs. Not; 2. Latino-Hispanic vs. Not, 3. Asian vs. Not; 4. Native American; 5. Pacific Islander vs. Not). However, because race/ethnicity analyzed in this way did not significantly contribute to any of the outcomes we examined, we collapsed the categories into one overarching dummy variable (White = 0, Non-White = 1) for inclusion as a covariate. Perceived number of friends who smoked during adolescence was obtained by averaging responses to the following question asked in CDS-II and CDS-III: “Of your 3 best friends, how many smoke at least 1 cigarette a day?” Family income-to-needs ratio is a measure of economic well-being that takes into account the needs of the family (based on size) relative to income. As such, it is recognized as a more sensitive and accurate measure of disposable income than income alone, with higher scores indicating higher levels of disposable income (McLoyd, 1998). It is computed by dividing reported family income by the poverty threshold appropriate to the size of the family provided by the Census Bureau. Family income-to-needs ratios were calculated separately for each CDS wave then averaged across the three waves to capture the average family-income-to-needs ratio experienced by young adults while growing up. Education level of household head is determined by the number of years of education completed.

Statistical Analysis

In order to assess the question of whether there were direct relationships between G1 and G2 smoking, G2 and G3 smoking, and G1 and G3 smoking, respectively, we conducted three separate logistic regressions. Two logistic regressions were conducted with G3 (young adult) smoking as the outcome, and with either G2 (parent) or G1 (grandparent) smoking as the predictor of interest, respectively. One logistic regression was conducted with G2 (parent) smoking as the outcome, with G1 (grandparent) smoking as the predictor of interest. In regressions predicting G3 (young adult) smoking, young adult age, gender, ethnicity, perceived number of friends who smoked during adolescence, family income-to-needs ratio, and number of years of education of the head of household were included in the models as covariates. Regressions predicting parent (G2) smoking control for all of the above except number of friends who smoked during adolescence.

In order to examine whether the transmission of smoking from grandparents to young adults was significantly mediated by parent smoking, we conducted a Sobel test (Sobel, 1982) utilizing the approach advocated by Kraemer, Stice, Kazdin, Offord, and Kupfer (2001) modified for logistic regression models. The coefficients obtained from the logistic regression were standardized prior to completing the Sobel test due to the fact that variables have different scales when examined as predictor versus response variables in logistic regressions (Sobel, 1982).

Analyses were conducted in Stata 12 using survey weighted data. In order to account for the clustering of individuals within families, analyses were conducted with robust standard errors, which correct standard errors for the nonindependence of data from individuals within the same families. Without this correction, the standard errors would be incorrectly deflated resulting in biased significance testing (Moulton, 1986).

RESULTS

The unweighted smoking prevalence for each generation and descriptive information for all covariates utilized in analyses are presented in Table 1. The prevalence of ever smoking was highest among grandparents (G1, 79.7%), followed by parents (G2, 61.2%), and young adult offspring (G3, 16.4%).

Table 1.

Descriptive Statistics

| Percentage or mean (SD)a | |

|---|---|

| Cigarette smoking | |

| Young adult current smoker (G3) | 20.2% |

| Men | 25.3% |

| Women | 12.8% |

| Parent (G2) | |

| Current smoker | 25.8% |

| Ever smoked | 61.2% |

| Grandparent (G1) | |

| Current smoker | 11.2% |

| Ever smoked | 79.7% |

| Covariates | |

| Young adult age | 20.72 (2.40) |

| Young adult percent female | 46.8% |

| Young adult percent non-White | 50.7% |

| Perceived number of best friends who smoked in adolescence | 0.28 (0.63) |

| Family income-to-needs ratiob | 3.13 (2.84) |

| Number of years of education | 13.04 (2.26) |

Note. SD = standard deviation.

aUnweighted percentages and means are presented.

bFamily income-to-needs ratio is the average family income-to-needs ratio from childhood to late adolescence (Child Development Supplement Waves 1–3).

Direct Links in Smoking Behavior Between Generations

Logistic regressions assessing the direct links between ever smoking in each possible pair of the three generations are presented in Table 2. These analyses revealed significant links between smoking behaviors for the two most proximal generational pairs. Having a parent who ever smoked (G2) was associated with increased odds of current smoking among young adults (G3) (odds ratio [OR] = 2.91; 95% CI = 1.60–5.31), while having a grandparent (G1) who ever smoked was associated with increased odds of ever smoking among parents (G2) (OR = 4.53; 95% CI = 2.57–7.97). Although we have labeled the generations from the young adult perspective (G3), these are essentially the same links—smoking behavior between parents and offspring—for two different generations. Although the relationship between ever smoking in grandparents (G1) and current smoking in young adults (G3) did not reach significance (OR = 2.25; 95% CI = 0.96–5.23, p < .10), it is worth noting that the OR indicated that G3 members were more than 2 times more likely to smoke if G2 members ever smoked. Similar to ever smoking, the odds of current smoking among young adults (G3) increased with current smoking in parents (G2; R = 2.30; 95% CI = 1.25–4.25) and grandparents (G1; OR = 2.49; 95% CI = 1.06–5.84). Likewise, the odds of current smoking among parents (G2) increased with current smoking in grandparents (G3; OR = 2.17; 95% CI = 0.98–4.80; See Table 3).

Table 2.

Odds Ratios for the Intergenerational Transmission of Ever-Smoking (N = 830)

| Young adult smokes (G3) OR [95% CI] | Parent ever smoked (G2) OR [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|

| Parent ever smoked (G2) | 2.91*** [1.60–5.31] | — |

| Grandparent ever smoked (G1) | 2.25t [0.96–5.23] | 4.53*** [2.57–7.97] |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Regressions predicting young adult smoking control for young adult age, gender, ethnicity, perceived number of friends who smoked during adolescence, family income-to-needs ratio and number of years of education of household head. Regressions predicting parent smoking control for all of the above except number of friends who smoked during adolescence. All analyses utilize population weights and account for dependencies in the data via robust standard errors in Stata 12.

t = p < .10, ***p < .001.

Table 3.

Odds Ratios for the Intergenerational Transmission of Current Smoking

| Young adult smokes (G3) OR [95% CI] | Parent smokes (G2) OR [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|

| Parent smokes (N = 568) | 2.30** [1.25–4.25] | — |

| Grandparent smokes (N = 400) | 2.49* [1.06–5.84] | 2.17t [0.98–4.80] |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Regressions predicting young adult smoking control for young adult age, gender, ethnicity, perceived number of friends who smoked during adolescence, family income-to-needs ratio and number of years of education of household head. Regressions predicting parent smoking control for all of the above except number of friends who smoked during adolescence. All analyses utilize population weights and account for dependencies in the data via robust standard errors in Stata 12.

t = p < .10,*p < .05, **p < .01.

As a follow-up to these analyses, we addressed the question of whether the intergenerational transmission of smoking might differ by the gender of different generation members. These analyses were restricted to G2 (parents) and G3 (young adults) members, due to the small sample sizes available to examine relationships between G1 (grandparents) and G2 (parents) or between G1 (grandparents) and G3 (young adults).

Analyses revealed that ignoring young adult gender, mother’s current smoking was related to significantly higher the odds of young adult smoking (OR = 2.80; 95% CI = 1.57–4.99, p < .001) while father’s current smoking was not (OR = 1.60; 95% CI = 0.73–3.50).

Considering these relationships for young adults of different genders, both mother’s (OR = 4.02; 95% CI = 2.00–8.08) and father’s (OR = 2.64; 95% CI = 1.00–7.01) current smoking increased the odds of current smoking among young adult males (G3). In contrast, neither mother’s (OR = 1.80; 95% CI = 0.65–5.02) nor father’s (OR = 0.83; 95% CI = 0.22–3.11) current smoking increased the odds of current smoking among young adult females (G3; see Table 4).

Table 4.

Odds Ratios Examining the Impact of Young Adult (G3)—Parent (G2) Gender Match on the Transmission of Current Smoking

| Young adult male smokes (G3) OR [95% CI] | Young adult female smokes (G3) OR [95% CI] | |

|---|---|---|

| Mother current smoker (N = 422) | 4.02*** [2.00–8.08] | |

| Father current smoker (N = 274) | 2.64* [1.00–7.01] | |

| Mother current smoker (N = 373) | 1.80 [0.65–5.02] | |

| Father current smoker (N = 235) | 0.83 [0.22–3.11] |

Note. OR = odds ratio; CI = confidence interval. Regressions predicting young adult smoking control for young adult age, gender, ethnicity, perceived number of friends who smoked during adolescence, family income-to-needs ratio and number of years of education of household head. All analyses utilize population weights and account for dependencies in the data via robust standard errors in Stata 12.

*p < .05, **p < .01, ***p < .001.

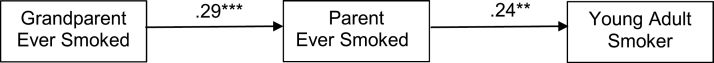

Intergenerational Pathways of Smoking

Conceptually, intergenerational pathways represent the notion that transmission of behavior is passed from one generation to the next generation, then to the generation following that, and so forth. This is essentially the question of whether the link between G1 and G3 smoking is mediated by G2 smoking. This mediation model is presented in Figure 1. As shown in the figure, G1 smoking significantly predicts G2 smoking, which in turn significantly predicts G3 smoking. The Sobel test of mediation (Sobel, 1982) was significant (Sobel’s t = 2.85, p < .01) indicating that parental (G2) smoking significantly mediated the connection between grandparent (G1) smoking and young adult (G3) smoking. Because the mediation was not perfect, we can assume that risk factors beyond parental smoking contribute to the uptake of smoking among their children. The total effect of both previous generations (G1 and G2) ever smoking on young adult (G1) current smoking was calculated (Soper, 2012b) as 0.48, which is fairly large. The magnitude of the indirect effect of grandparent (G1) ever smoking on young adult (G3) current smoking was calculated (Soper, 2012a) as 0.15, indicating a moderate indirect effect of grandparent (G1) smoking on smoking among their grandchildren (G3; Cohen, 1988; Shrout & Bolger, 2002). Thus, the mediation analysis confirmed the notion that smoking behavior is passed from one generation to the next generation, and in turn to the next generation.

Figure 1.

The intergenerational transmission of smoking across three generations. Note. **p < .01, ***p < .001. Path coefficients represent standardized coefficients from logistic regression. Sobel test for mediation = 2.47, p < .01. Magnitude of indirect effect from grandparent ever smoked to young adult smoker = .15.

DISCUSSION

While a fair amount is known about the transmission of smoking across two generations (typically parents and their adolescent or young adult children), examination of the transmission of smoking behaviors across multiple generations are scarce, and to the best of our knowledge, none are based on a representative sample of the U.S. population. In the current analysis, we examined smoking behavior across three generations in a U.S. representative sample. We found that regardless of generation, parents’ smoking behavior had a direct significant influence on their children’s smoking behavior. Though the direct link between grandparent ever smoking (G1) and young adult smoking (G3) did not achieve significance, the OR indicated that ever smoking in grandparents increased the odds of young adult smoking by roughly 2 times. However, tests of mediation indicated that parental smoking significantly mediated the links between young adult smoking and the smoking behavior of their grandparents. Thus, in contrast to a model where smoking in earlier generations directly affects smoking in all following generations, our results indicated that smoking behaviors are transferred from preceding generations to later generations with the strongest links between the two most proximal generations.

Our results replicate and extend existing findings (Melchior et al., 2010), suggesting that there is an association between parental smoking behavior and the smoking behavior of their immediate offspring (Chassin, Presson, Todd, Rose, & Sherman, 1998). The significant association between ever and current smoking in parents and the risk of smoking in offspring is consistent with evidence indicating that a parent’s historical smoking trajectory may provide a developmental phenotype that can be transmitted between generations (Chassin et al., 2008). This suggests that the shared smoking behavior of parents and their offspring represents the combined influence of the family social environment, as well as shared genetic factors affecting smoking initiation and nicotine addiction.

As one would expect based on cross-sectional examinations of smoking prevalence in different cohorts, the percent of ever smoking in each generation examined in this study has decreased (from roughly 80% of grandparents to 61% of parents to 16% of young adults; Fiore et al., 1989). Thus, the greater odds of G2 smoking predicted from G1 smoking, relative to the odds of G3 smoking (who were aged 20 on average in 2011) as predicted by G2 smoking, may reflect differences in the prevalence of smoking in different cohorts.

Historically, the prevalence of smoking in the U.S. population has fallen precipitously from the 1960s to the present day. Indeed, one of the reasons the original 1968 PSID question only asked about household level smoking was because so much of the population smoked that asking whether anyone in the household smoked or not was enough. It seems likely that the smaller relationship between parent and offspring smoking we found in the later generation relative to the earlier generation is a reflection of these historical changes in the prevalence of smoking in the United States overtime. Nonetheless, given the far smaller prevalence of smoking in current generations relative to older generations, it is notable that we still found evidence that smoking behavior is passed from one generation to the next (G1 to G2), and in turn to the next generation (G2 to G3). The prevalence of smoking at the population level has decreased over time as both the dissemination of information regarding the dangers of smoking and taxation on cigarettes has increased (Evans, Ringel, & Stech, 1999; Warner, 1977). If the prevalence of smoking in future generations decreases even further, it is possible that the link between parent and offspring smoking behavior may disappear altogether.

When examining whether the transmission of smoking between the parent and young adult dyad is influenced by the gender of the parent, we found that mothers exerted a stronger and significant influence on their children compared with fathers. This finding is consistent with previous research examining current smoking (Hu, Flay, Hedeker, Ohidul & Day, 1995), experimentation with cigarettes (White, 2012) and correlates of cognitive susceptibility to smoking (Wilkinson et al., 2008). Thus, it appears that mothers exert a stronger influence than fathers on both the intergenerational transfer of smoking as well as their children’s progression through the smoking trajectory—from susceptibility to current smoking.

When examining whether the transmission of smoking between the parent and young adult dyad is influenced by the gender of the dyad, we found that both mothers and fathers exerted a significant influence on their sons but not on their daughters. Consistent with this result, Ashley et al. (2008) reported that smoking by the father is more strongly associated with sons smoking relative to daughters. However, in contrast to our results, Ashley et al. also reported that mother smoking was associated with smoking by daughters but not sons.

We do not fully understand why mothers exert a stronger influence than fathers on their children’s behavior, nor do we understand why sons appear to be more receptive to the influence from their parents compared with daughters. It is possible that because mothers historically and still assume the primary responsibility for parenting and spend more time with their children (Parker & Wang, 2013) than fathers, the overall influence of their behavior, especially in terms of modeling behaviors, is stronger. Yet, we also found that sons, and not daughters, were influenced by both parents. Interestingly, the only predictor of daughter’s smoking in these models was the perceived number of friends who smoked during adolescence (OR = 2.55 for mothers; OR = 2.58 for fathers). This may reflect the closer social ties of women and a greater receptivity to social influence related to smoking in general (Li & Delva, 2011). For example, there is evidence that girl’s decisions to smoke are influenced by their peers, while boys are not (Mercken, Snijders, Steglich, Vertiainen, & de Vries, 2010).

Study Limitations and Strengths

This study has several limitations worth noting. First, although the longitudinal study design strengthens our ability to make inferences regarding the direction of the associations we examine (i.e., from grandparent to parent to young adult smoking), it is important to acknowledge that causal conclusions cannot be drawn. Additionally, we would note that few, if any, researchers in this area have attended to dependencies inherent in family data. We utilize robust standard errors, which, though not as powerful as multilevel modeling, require fewer assumptions and sample size (Moulton, 1986). Moreover, the Sobel test, though the best option available to us currently, uses a normal approximation which presumes a symmetric distribution. Thus, it falsely presumes symmetry with the result that it is an overly conservative test of mediation.

Second, we do not know how much time grandparents actually spent with their grandchildren, which might impact the direct transmission of smoking from grandparents to grandchildren. For example, when children are raised by their grandparents, they experience greater academic difficulties and are susceptible to developing a wide range of emotional and behavioral problems, which may increase their risk of problem behaviors such as smoking (Edwards, 2006; Solomon & Marx, 1995). Additionally, increased smoking is a common coping mechanism for the stress that many grandparent caregivers experience, and as such, this could further influence the transmission of these behaviors from grandparents to grandchildren (Burton, 1992; Waldrop & Weber, 2005). Third, while we were able to control for two of the strongest risk factors for experimenting with cigarettes and subsequent smoking (family and peer influences), we were not able to control for other factors associated with smoking behavior among youth and young adults, such as outcome expectations and sensation-seeking tendencies (Morrell, Song, & Halpern-Felsher, 2010; Wilkinson et al., 2012).

However, this study also has some important strengths. First, it is among the first to examine the intergenerational transfer of smoking behavior across three generations, rather than being limited to only two generations at a time. Second, the population representative nature of the sample means that the results are generalizable to the entire U.S. population, a considerable strength. Third, the PSID has excellent follow-up rates (96%–98%), which reduces the chance that there is bias present within our results due to attrition, and further ensures that the results are generalizable to the larger population.

CONCLUSIONS

This study provides evidence that regardless of generation, the smoking behaviors of parents have an important influence on their children’s smoking behaviors, and that these behaviors are passed on from one generation to the next. These findings stress the need for more comprehensive tobacco prevention and intervention programming that addresses influences at the family level. Since these family influences represent both genetic and environmental factors, further research is needed to determine how much of the intergenerational transmission of smoking behaviors can be attributed to genetic versus environmental influence. However, targeting the family level for intervention may help to lessen the effect of these specific environmental influences, and in doing so, simultaneously help to increase protective factors for those who may be genetically predisposed to these behaviors.

FUNDING

The research reported here was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants (5R01-HD053652 to EAV and K07-CA126988 to AVW).

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

None declared.

REFERENCES

- Ashley O. S., Penne M. A., Loomis K. M., Kan M., Bauman K. E., Aldridge M, … Novak S. P. (2008). Moderation of the association between parents and adolescent cigarette smoking by selected socio demographic variables. Addictive Behaviors, 33, 1227–1230.10.1016/ j.addbeh.2008.04.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenevoli S., Merikangas K. R. (2003). Familial influences on adolescent smoking. Addiction (Abingdon, England), 98(Suppl. 1, 1–20.10.1046/j.1360-0443.98.s1.2.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantle C., Haisken-DeNew J.P. (February 2002). Smoke signals: The intergenerational transmission of smoking behavior. DIW Discussion Paper No. 277. DIW Berlin: German Institute for Economic Research. Retrieved from http://ssrn.com/abstract=381381

- Benowitz N. L. (2010). Nicotine addiction. The New England Journal of Medicine, 362, 2295–2303.10.1056/NEJMra0809890 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bricker J. B., Otten R., Liu J., Peterson A. V., Jr (2009). Parents who quit smoking and their adult children’s smoking cessation: A 20-year follow-up study. Addiction, 104, 1036–1042.10.1111/j.1360-0443.2009.02547.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Burton L. M. (1992). Black grandparents rearing children of drug-addicted parents: Stressors, outcomes, and social service needs. The Gerontologist, 32, 744–751.10.1093/geront/32.6.744 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2011). Tobacco use: Targeting the nation’s leading killer: At a glance 2011. Atlanta, GA: National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion; [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L., Presson C., Seo D. C., Sherman S. J., Macy J., Wirth R., Curran P. (2008). Multiple trajectories of cigarette smoking and the intergenerational transmission of smoking: A multigenerational, longitudinal study of a midwestern community sample. Health Psychology, 27, 819–828.10.1037/0278-6133.27.6.819 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chassin L., Presson C. C., Todd M., Rose J. S., Sherman S. J. (1998). Maternal socialization of adolescent smoking: The intergenerational transmission of parenting and smoking. Developmental Psychology, 34, 1189–1201.10.1037/0012-1649.34.6.1189 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2 nd ed.). Hillsdale, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- den Exter Blokland E. A. W., Engels R. C. M. E., Hale W. W., III, Meeus W., Willemsen M. C. (2004). Lifetime parental smoking history and cessation and early adolescent smoking behavior. Preventative Medicine, 38, 359–368.10.1016/j.ypmed.2003.11.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Edwards O. W. (2006). Teachers’ perceptions of the emotional and behavioral functioning of children raised by grandparents. Psychology in the Schools, 43, 565–572.10.1002/pits.20170 [Google Scholar]

- Evans W. N., Ringel J. S., Stech D. (1999). Tobacco taxes and public policy to discourage smoking. In Poterba J. M. (Ed.), Tax policy and the economy (pp. 1–56). Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press; [Google Scholar]

- Fiore M. C., Novotny T. E., Pierce J. P., Hatziandreu E. J., Patel K. M., Davis R. M. (1989). Trends in cigarette smoking in the united states: The changing influence of gender and race. The Journal of the American Medical Association, 261, 49–55.10.1001/jama.1989.03420010059033 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilman S. E., Rende R., Boergers J., Abrams D. B., Buka S. L., Clark M. A., Niaura R. S. (2009). Parental smoking and adolescent smoking initiation: An intergenerational perspective on tobacco control. Pediatrics, 123, e274–281.10.1542/peds.2008–2251 10.1542/peds.2008–2251 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gohlmann S., Schmidt C. M., Tauchmann H. (2010). Smoking initiation in germany: The role of intergenerational transmission. Health Economics, 19, 227–242.10.1002/hec.1470 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Groves R. M., Fowler F. J., Jr, Couper M. P., Lepkowski J. M., Singer E., Tourangeau R. (2004). Survey Methodology. Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley & Sons; [Google Scholar]

- Hu F.B., Flay B. R., Hedeker D., Ohidul S., Day L.E. (1995). The influence of friends and parental smoking on adolescent smoking behavior: The effects of time and prior smoking. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 25, 2018–2047.10.1111/j.1559–1816.1995.tb01829.x [Google Scholar]

- Jackson C., Henriksen L., Dickinson D., Levine D. W. (1997). The early use of alcohol and tobacco: Its relation to children’s competence and parents’ behavior. American Journal of Public Health, 87, 359–364.10.2105/AJPH.87. 3.359 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kong G., Camenga D., Krishnan-Sarin S. (2012). Parental influence on adolescent smoking cessation: Is there a gender difference? Addictive Behaviors, 37, 211–216.10.1016/ j.addbeh.2011.10.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kraemer H. C., Stice E., Kazdin A., Offord D., Kupfer D. (2001). How do risk factors work together? Mediators, moderators, and independent, overlapping, and proxy risk factors. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 158, 848–856.10.1176/appi.ajp.158.6.848 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leonardi-Bee J., Jere M. L., Britton J. (2011). Exposure to parental and sibling smoking and the risk of smoking uptake in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax, 66, 847–855.10.1136/thx.2010.153379 10.1136/thx.2010.153379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li S., Devla J. (2011). Does gender moderate associations between social capital and smoking? An Asian American study. Journal of Health Behavior and Public Health, 1, 41–49 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling P. M., Glantz S. A. (2002). Why and how the tobacco industry sells cigarettes to young adults: Evidence from industry documents. American Journal of Public Health, 92, 908–916.10.2105/AJPH.92.6.908 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McGonagle K. A., Schoeni R. F. (2006). The panel study of income dynamics: Overview and summary of scientific contributions after nearly 40 years. Conference on Longitudinal Social and Health Surveys in an International Perspective Montreal [Google Scholar]

- McLoyd V. C. (1998). Socioeconomic disadvantage and child development. The American Psychologist, 53, 185–204.10.1037/0003-066X.53.2.185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Melchior M., Chastang J. F., Mackinnon D., Galera C., Fombonne E. (2010). The intergenerational transmission of tobacco smoking—the role of parents’ long-term smoking trajectories. Drug and Alcohol Dependence, 107, 257–260.10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2009.10.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mercken L., Snijders T. A., Steglich C., Vertiainen E., de Vries H. (2010). Smoking-based selection and influence in gender-segregated friendship networks: A social network analysis of adolescent smoking. Addiction, 105, 1280–1289.10.1111/j.1360-0443.2010.02930.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morrell H. E., Song A. V., Halpern-Felsher B. L. (2010). Predicting adolescent perceptions of the risks and benefits of cigarette smoking: A longitudinal investigation. Health Psychology, 29, 610–617.10.1037/a0021237 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moulton B. R. (1986). Random group effects and the precision of regression estimates. Journal of Econometrics, 32 385–397 [Google Scholar]

- Parker K., Wang W. (2013). Modern parenthood. Roles of moms and dads converge as they balance work and family. Washington, DC: Pew Report. Pew Research Center; [Google Scholar]

- Shrout P. E., Bolger N. (2002). Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: New procedures and recommendations. Psychological Methods, 7, 422–445.10.1037/1082-989X.7.4.422 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sobel M. E. (1982). Asymptotic intervals for indirect effects in structural equations models. In Leinhart S. (Ed.), Sociological methodology (pp. 290–312). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; [Google Scholar]

- Solomon J. C., Marx J. (1995). “To grandmother’s house we go”: Health and school adjustment of children raised solely by grandparents. The Gerontologist, 35, 386–394.10.1093/geront/35.3.386 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soper D. S. (2012a). Indirect effect calculator for mediation models (online software) Retrieved from http://www. danielsoper.com/statcalc3/calc.aspx?id=32 [Google Scholar]

- Soper D. S. (2012b). Total effect calculator for mediation models (online software) Retrieved from http://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc3/calc.aspx?id=60 [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (1994). Preventing tobacco use among young people: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2012). Preventing tobacco use among youth and young adults: A report of the surgeon general. Atlanta, GA: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion, Office on Smoking and Health; [Google Scholar]

- Waldrop D. P., Weber J. A. (2005). From grandparent to caregiver: The stress and satisfaction of raising grandchildren. In Turner F. J. (Ed.), Social work diagnosis in contemporary practice (pp. 184–195). New York, NY: Oxford University Press, Inc; [Google Scholar]

- Warner K. E. (1977). The effects of the anti-smoking campaign on cigarette consumption. American Journal of Public Health, 67, 645–650.10.2105/AJPH.67.7.645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- White J. (2012). The contribution of parent-child interactions to smoking experimentation in adolescence: Implications for prevention. Health Education Research, 27, 46–5610.1093/her/cyr067 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson A. V., Okeke N. L., Springer A. E., Stigler M. H., Gabriel K. P., Bondy M. L., Spitz M. R. (2012). Experimenting with cigarettes and physical activity among mexican origin youth: A cross sectional analysis of the interdependent associations among sensation seeking, acculturation, and gender. BMC Public Health, 12, 332.10.1186/1471-2458-12-332 10.1186/1471-2458-12-332 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson A. V., Shete S., Prokhorov A. V. (2008). The moderating role of parental smoking on their children’s attitudes toward smoking among a predominantly minority sample: A cross-sectional analysis. Substance Abuse Treatment, Prevention, and Policy, 3, 18.10.1186/1747-597X-3–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wilkinson A. V., Waters A. J., Vasudevan V., Prokhorov A. V., Bondy M. L., Spitz M. R. (2008). Correlates of smoking susceptibility among Mexican origin youth. BMC Public Health, 8, 337.10.1186/1471-2458-8-337 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]