Abstract

Context

Data supporting physical activity guidelines to prevent long-term weight gain are sparse, particularly during the period when the highest risk of weight gain occurs.

Objective

To evaluate the relationship between habitual activity levels and changes in body mass index (BMI) and waist circumference over 20 years.

Design, Setting, and Participants

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study is a prospective longitudinal study with 20 years of follow-up, 1985-86 to 2005-06. Habitual activity was defined as maintaining high, moderate, and low activity levels based on sex-specific tertiles of activity scores at baseline. Participants comprised a population-based multi-center cohort (Chicago, Illinois; Birmingham, Alabama; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Oakland, California) of 3554 men and women aged 18 to 30 years at baseline.

Main Outcome Measures

Average annual changes in BMI and waist circumference

Results

Over 20 years, maintaining high levels of activity was associated with smaller gains in BMI and waist circumference compared with low activity levels after adjustment for race, baseline BMI, age, education, cigarette smoking status, alcohol use, and energy intake. Men maintaining high activity gained 2.6 fewer kilograms (+ 0.15 BMI units per year; 95 % confidence interval [CI] 0.11-0.18 vs +0.20 in the lower activity group; 95% CI, 0.17-0.23) and women maintaining higher activity gained 6.1 fewer kilograms (+0.17 BMI units per year; 95 % CI, 0.12-0.21 vs. +0.30 in the lower activity group; 95 % CI, 0.25-0.34). Men maintaining high activity gained 3.1 fewer centimeters in waist circumference (+0.52 cm per year; 95 % CI, 0.43-0.61 cm vs 0.67 cm in the lower activity group; 95 % CI, 0.60-0.75) and women maintaining higher activity gained 3.8 fewer centimeters (+0.49 cm per year; 95 % CI, 0.39-0.58 vs 0.67 cm in the lower activity group; 95 % CI, 0.60-0.75).

Conclusion

Maintaining high activity levels through young adulthood may lessen weight gain as young adults transition to middle age, particularly in women.

Introduction

The prevalence of obesity (body mass index [BMI {calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared}]) has risen markedly since 1976, now exceeding 30% among US adults.1 Obesity has well-known associations with morbidity and disability, resulting in unhealthy life-years and increased health care costs.2,3 Although many studies have examined obesity treatment (weight loss through lifestyle intervention, pharmacotherapy, or surgery), research on obesity prevention (preventing or decreasing the amount of weight gain) is less abundant.4,5 Public health guidelines recommend regular physical activity to minimize age-related weight gain,6-8 implying that weight gain may be prevented by maintaining high activity levels over time. However, these recommendations are largely based on cross-sectional observational and short-term clinical evidence that cannot account for the changing risk of weight gain with increasing age.9,10 Data on the amount of activity necessary for prevention of weight gain are also sparse. Although a 2008 report from the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) advocates at least 30 minutes of moderate-intensity activity 5 days per week,11 a recent study observed that HHS-recommended activity levels were insufficient for weight gain prevention in middle-aged women (mean, 54.2 years at baseline).12 It is unclear if federal activity guidelines are sufficient to prevent weight gain, particularly in the transition from young adulthood to middle age where the highest risk of weight gain occurs.13 This study evaluates the relationship between maintaining higher activity levels, including HHS-recommended levels, and changes in BMI and waist circumference over 20 years in young adults. Because participation in activity varies by race, sex, and weight status, 11,14 this study also examine if these factors modify the relationship between activity and weight gain. We hypothesize that maintaining higher levels of moderate and vigorous activity will be associated with smaller increases in BMI and waist circumference as young adults transition to middle age.

Methods

The Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study is a multicenter longitudinal cohort study designed to investigate the development of coronary heart disease risk factors in young adults. The initial cohort consisted of 5115 young adult participants, balanced by age (18-24 years and 25-30 years), sex, race (black and white), and educational status (≤ high school graduate, > high school education). Details about eligibility criteria and baseline demographic characteristics have been previously published.15 Participants from 4 US cities (Birmingham, Alabama; Chicago, Illinois; Minneapolis, Minnesota; and Oakland, California) were initially examined in 1985-86. Follow-up examinations were performed 2, 5, 7, 10, 15, and 20 years after baseline with retention of the cohort of 91%, 86%, 81%, 79%, 74%, and 72%, respectively. The study was approved by the institutional review board at each center and written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Physical Activity Measurement

At each examination, physical activity was measured using the interviewer-administered CARDIA Physical Activity History questionnaire. This instrument was specifically designed to assess usual activity during a period of time (ie, 1 year). The questionnaire asks about participation in 13 specific moderate- and vigorous-intensity activities over the previous year, including sports, exercise, home maintenance, and occupational activities. Each activity was assigned an intensity score (ranging from 3-8 metabolic equivalents) and a duration threshold (ranging from 2-5 hours/week), above which participation was considered to be frequent. Questions did not include details about activity duration. Thus, duration threshold represents the minimum duration for each activity. The activities included in the questionnaire, along with the intensity and duration threshold for frequent participation, are included in eTable 1 (available at http://www.jama.com). The questionnaire was computer scored using an algorithm described in detail elsewhere.16 In brief, the algorithm computed a score for each activity based on the intensity score, frequency, and a weighting factor to represent duration. The total activity score was the sum of scores for all activities, expressed in exercise units, which represent the usual level of activity over the previous 12 months. For reference, a total activity score of 300 exercise units approximates HHS recommendations of at least 150 minutes of moderate-intensity activity per week.17 Exercise units are related to caloric expenditure, but because the questionnaire did not ask detailed questions about activity duration, caloric expenditure could not be directly estimated. The CARDIA activity questionnaire shows test-retest reliability in the range of 0.77-0.84 and scores on the questionnaire are associated with external validation criteria. Details of the scoring system have previously been published.16

Other Measurements

At each examination, height, weight, and waist circumference were measured with participants wearing light examination clothes and no shoes. Normal weight, overweight, and obesity were defined as BMI of 18.5 to 24.9, 25.0 to 29.9, and 30.0 or greater, respectively. Age, self-reported race, years of education, cigarette smoking status, and alcohol use were ascertained by interview at each examination and cardiorespiratory fitness was assessed by duration on a symptom-limited treadmill test at baseline. At baseline, year 7, and year 20, energy intake was determined from a CARDIA-specific interviewer-administered dietary history assessment, which includes a quantitative food frequency tool and nutrient measures expressed as intake per day. The reliability and validity of this instrument have previously been reported; validity correlations are generally above 0.50.18 Extreme high and low values of energy intake (>8000 kcal in men and >6000 kcal in women; and <800 kcal in men and <600 kcal in women, respectively) were excluded as unreliable.

Habitual Activity Categories

Because activity varies widely within individuals across time, categories were created to reflect long-term, or habitual activity levels over 20 years. Sex-specific tertiles for activity scores at baseline examination were calculated and habitual activity levels were defined as maintaining sex-specific baseline activity thresholds at two-thirds of follow-up CARDIA examinations. Habitual high, moderate, or low activity levels were defined as maintaining activity scores greater than the baseline upper tertile, middle tertile, or below the lowest tertile, respectively, at two-thirds of follow-up CARDIA examinations. Any other pattern of activity was defined as inconsistent. An additional analysis was performed with high/low habitual activity dichotomized based on maintenance of HHS activity recommendations at baseline and two-thirds of follow-up CARDIA examinations.

Exclusions

For the present analysis, 1561 (31.5%) participants were excluded for the following reasons (not mutually exclusive): missing activity scores (n=250), attending fewer than 5 CARDIA examinations (n=1117), missing BMI measurement at baseline (n=17), transgender sex (n=2), pregnancy at any examination (n=237), or having undergone bariatric surgery by year 20 (n=42). The remaining 3554 participants were included, representing 69.5% of the initial CARDIA cohort.

Statistical Analysis

Participation in activity varied by race, gender, and weight status;11,14 therefore, formal tests for effect modification were performed by examining 2-way cross-product terms of activity categories with male sex, black race, and baseline weight status (normal weight or overweight/obese) in separate models. Significant terms were found with male sex (P=.003), therefore, all analyses were stratified by sex. In sensitivity analyses, effect modification by 20-year parity status (nulliparous/not nulliparous) within the female strata was also evaluated. Differences in selected baseline characteristics were compared and pairwise differences in covariates by activity categories were estimated using 1-way analysis of variance and χ2 tests for continuous and categorical variables, respectively. Within each sex group, Spearman partial correlation coefficients were calculated to evaluate the cross-sectional relationship between activity score and BMI or waist circumference. Correlations at each CARDIA examination were adjusted for age, alcohol use, education, cigarette smoking status, and energy intake. General linear models were used to compare mean energy intake and estimate pairwise differences in energy intake by activity categories at each year in which dietary history was collected (baseline, year 7, year 20). The generalized estimating equations method (PROC GENMOD version 9.2, SAS Institute Inc, Cary, North Carolina), was used to estimate the relation of habitual activity categories with average annual changes in BMI over 20 years. The independent variable was the habitual activity category (high, moderate, low, or inconsistent), and the dependent variable was time-dependent BMI. Time was treated as a continuous variable, while activity categories were treated as indicator variables, with low activity as a referent. We included cross-product terms of the indicator variables and time; the β coefficients for the cross-product terms indicated the magnitude of difference in average annual changes of BMI relative to the low activity group. Analyses were adjusted for race, baseline BMI; and time-dependent values for age, education, energy intake, number of cigarettes per day, and amount of alcohol intake per day (by milliliters). Longitudinal analyses were repeated using time-dependent waist circumference as the dependent variable.

Results

Comparison of Included and Excluded Participants

In unadjusted analyses, compared with included participants, excluded CARDIA participants at baseline were younger (mean [SD], 24.4 [3.7] years vs 25.1 [3.6] years), had lower physical activity scores (404.3 [297.9] exercise units vs 427.1 [301.7] exercise units), had larger percentages of women (59.1% vs 52.5%), larger percentages of black individuals (60.7% vs 47.5%). Baseline anthropometric measures were similar for excluded and included participants, namely BMI (mean [SD], 24.6 [5.5] vs 24.4 [4.9] for men and women combined) and waist circumference (81.5 [10.0] cm vs 81.8 [9.3] cm for men, and 74.7 [12.6] cm vs 74.2 [11.4] cm for women).

Tertile Thresholds for Habitual Activity Categories

Sex-specific baseline activity tertiles, used to define habitual high, moderate, and low activity levels, had the following thresholds (in exercise units): for men, at least 608, 340 to 607, and less 340; and for women, at least 398, 192 to 397, and less than 192, respectively. An inconsistent pattern category was defined by not meeting criteria for other activity categories; therefore no activity threshold is set for the inconsistent pattern category.

Baseline Characteristics

The distribution of participants across habitual activity categories was similar by sex with 11% of women and 12% of men in the highest activity tertile at baseline maintained this level over 20 years (χ2 =6.0; P=.11). In unadjusted analyses, distribution of most baseline characteristics did not differ across activity categories, with the exceptions of race and baseline weight status (Table 1). Among women but not men, a smaller proportion of participants who were overweight/obese at baseline maintained higher activity levels over 20 years.

Table 1.

Characteristics at baseline, by long-term physical activity categoriesa

| Men by activity category (n=1689) | Women (n=1865) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower (n=477) | Moderate (n=102) | Higher (n=201) | Inconsistent (n=909) | Lower (n=475) | Moderate (n=104) | Higher (n=206) | Inconsistent (n=1080) | |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||||

| Age, y | 25.2 (3.5) | 25.0 (3.6) | 24.5 (3.5) | 25.0 (3.6) | 25.0 (3.8) | 25.1 (3.6) | 25.0 (3.5) | 25.2 (3.7) |

| Black race, No. (%)b | 423 (49.1) | 34 (33.3) | 103 (51.2) | 380 (41.8) | 330 (69.5) | 37 (35.2) | 59 (28.6) | 513 (47.5) |

| Education, y | 13.9 (2.5) | 14.4 (2.6) | 13.7 (2.2) | 14.0 (2.4) | 13.4 (2.1) | 14.1 (2.1) | 14.8 (2.1) | 14.0 (2.2) |

| Anthropometric characteristics | ||||||||

| BMIc | 24.7 (4.5) | 24.0 (3.7) | 24.0 (3.0) | 24.4 (3.6) | 25.5 (6.7) | 24.6 (5.7) | 22.7 (4.4) | 24.3 (5.2) |

| Waist circumference, cm | 82.9 (10.8) | 80.1 (8.3) | 80.4 (7.2) | 81.8 (8.8) | 76.4 (13.4) | 74.9 (12.1) | 70.7 (9.1) | 73.8 (10.6) |

| Overweight/obese, No. (%)d | 179 (37.5) | 28 (27.5) | 62 (30.9) | 318 (35.0) | 200 (42.1) | 33 (31.4) | 36 (17.5) | 351 (32.5) |

| Lifestyle characteristics | ||||||||

| Activity score, exercise units | 304.6 (203.8) | 523.7 (224.2) | 867.9 (366.5) | 553.9 (290.3) | 193.2 (168.2) | 354.8 (197.2) | 599.7 (301.8) | 360.1 (235.6) |

| Objective fitness test duration, min | 11.4 (2.2) | 12.7 (2.1) | 13.0 (1.9) | 12.2 (2.0) | 7.7 (1.9) | 8.6 (1.8) | 10.1 (2.3) | 8.7 (2.0) |

| Energy intake, kcal | 3072.6 (1252.0) | 3245.3 (1472.0) | 3855.8 (1535.0) | 3453.7 (1367.0) | 2174.3 (944.7) | 2137.6 (905.5) | 2373.8 (1067.0) | 2277.0 (964.9) |

| Cigarette smoking, No. (%) | 145 (31) | 24 (24) | 50 (25) | 259 (29) | 135 (29) | 32 (31) | 50 (25) | 281 (26) |

| Cigarette smoking, median (IQR), No./d | 12.0 (12.0) | 15.0 (13.5) | 10.0 (12.0) | 14.0 (13.0) | 10.0 (14.0) | 12.5 (12.0) | 9.0 (12.0) | 10.0 (14.0) |

| Alcohol intake, median (IQR), mL/d | 7.3 (20.5) | 14.3 (23.9) | 9.6 (22.5) | 9.6 (24.9) | 0.0 (7.2) | 2.4 (9.7) | 4.8 (12.2) | 2.4 (9.7) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range

Values are reported as mean (SD) unless otherwise indicated. Long-term physical activity categories are based on maintaining sex-specific baseline total activity score tertiles in at least two-thirds of follow-up examinations: lower activity, less than 340 exercise units (men) and less than 192 exercise units (women); moderate activity, 340 to 607 exercise units (men) and 192 to 397 exercise units (women); higher activity, at least 608 exercise units (men) and at least 398 exercise units (women); inconsistent patterns, all other patterns of activity. Means were compared using 1-way analysis of variance and proportions were compared using the χ2 test.

Values are significantly different among physical activity categories in men (P <.01)

BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Values are significantly different among physical activity categories in women (P <.001)

Cross sectional Analysis: Relationship of Activity With BMI and Waist Circumference

More consistently in women than men, Spearman partial correlation coefficients, adjusted for age, alcohol intake, education, cigarette smoking status, and energy intake demonstrated inverse correlations between activity score and BMI or waist circumference (Table 2).

Table 2.

Spearman partial correlation coefficients between BMI or waist circumference and activity scores at each examination

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CARDIA Examination Year | No. | BMIa | Waista | No. | BMIa | Waista |

| 0 | 1689 | 0.0172 | -0.0185 | 1865 | -0.1187 | -0.1335 |

| 2 | 1628 | 0.0003 | -0.0744 | 1811 | -0.1149 | -0.1242 |

| 5 | 1609 | -0.0297 | -0.0873 | 1784 | -0.1558 | -0.1763 |

| 7 | 1573 | -0.0723 | -0.1501 | 1727 | -0.1633 | -0.2081 |

| 10 | 1587 | -0.0367 | -0.1098 | 1745 | -0.2030 | -0.2208 |

| 15 | 1500 | -0.0896 | -0.1694 | 1650 | -0.2350 | -0.2553 |

| 20 | 1398 | -0.0959 | -0.1583 | 1584 | -0.3026 | -0.3140 |

BMI, body mass index; CARDIA, Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults.

BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared. P<.001 for all BMI and waist values except BMI for men at examination years 0,2,5, and 10; and waist value for men in year 0. Spearman partial correlation coefficients were adjusted for age, alcohol intake, education, cigarette smoking, and energy intake.

Difference in Energy Intake Between Highest and Lowest Activity Categories

In unadjusted analyses, men maintaining high activity reported greater mean energy intake at baseline (783 kcal [95% confidence interval {CI}, 455-1112 kcal]), year 7 (834 kcal [95% CI, 510-1159 kcal]), and year 20 (428 kcal [95% CI, 106-750 kcal]) compared with men maintaining low activity. Among women, baseline energy intake did not differ by activity category; however, women maintaining high activity reported greater mean energy intake at year 7 (367 kcal [95% CI, 138-595 kcal]) and at year 20 (365 kcal [95% CI, 147-584 kcal]) than women with low activity.

Mean BMI, Weight, and Waist Circumference at Each Examination, by Habitual Activity Categories

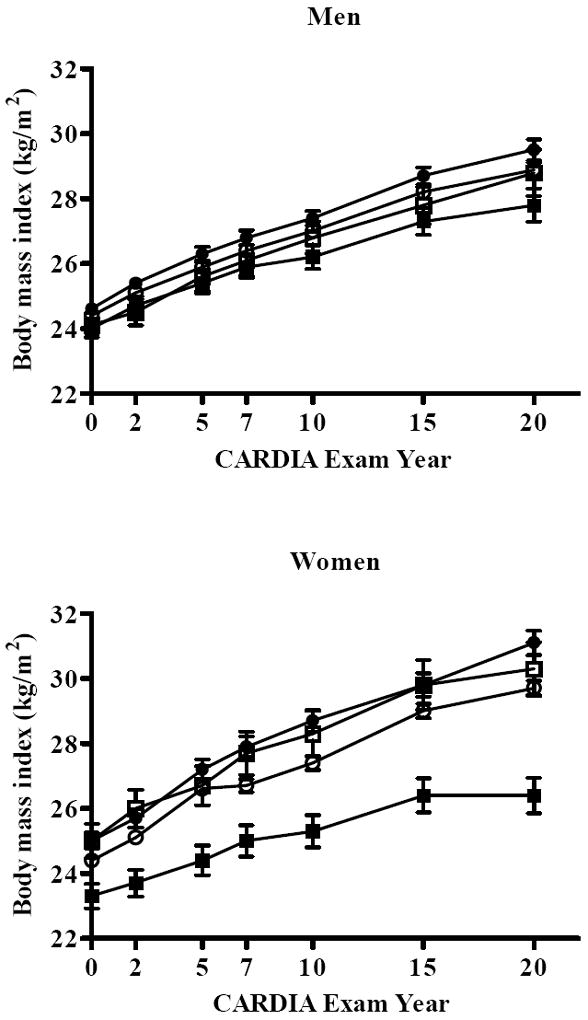

Mean BMI adjusted for age and race increased at each CARDIA examination, in all habitual activity categories for men and women (Figure). Similar patterns were observed for mean waist circumference (eFigure, available at http://www.jama.com). Unadjusted mean BMI, weight, and waist circumference at each examination are reported in eTable 2 and eTable 3).

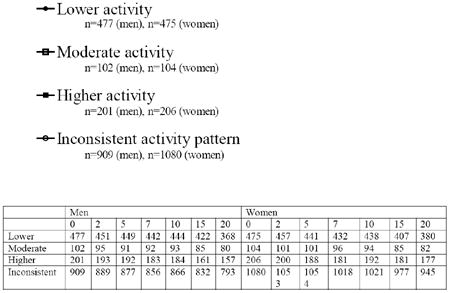

Figure. Least square mean* body mass index at each CARDIA visit, by habitual activity category.

*Least square means adjusted for age and race

Longitudinal Analysis: Relationship of Habitual Activity Level With Changes in BMI, Waist Circumference, and Weight

In analyses adjusted for race, baseline BMI, age, education, smoking status, alcohol use, and energy intake, habitual high activity was associated with smaller increases in mean BMI, waist circumference, and weight per year compared with low activity (Table 3, eTable 4). Average annual changes in BMI corresponded with the following cumulative weight changes over 20 years: men maintaining high activity gained 2.6 fewer kilograms (BMI increased in the high-activity group by 0.15 [95% CI, 0.11-0.18] per year vs a BMI increase of 0.20 per year in the low-activity group [95% CI, 0.17-0.23]) and women maintaining high activity high activity gained 6.1 fewer kilograms (BMI increased in the high-activity group by 0.17 [95% CI, 0.12-0.21] per year vs a BMI increase of 0.30 per year in the low-activity group [95% CI, 0.25-0.34]). Men maintaining high activity gained 3.1 fewer centimeters in waist circumference (high activity group gained 0.52 cm per year [95 % CI, 0.43-0.61 cm] vs 0.67 cm per year in the low-activity group [95 % CI, 0.60-0.75 cm]) and women maintaining high activity gained 3.8 fewer centimeters (high-activity group gained 0.50 cm per year [95 % CI, 0.40-0.60 cm] vs 0.68 cm per year in the low-activity group [95 % CI, 0.60-0.76 cm]). Patterns of association were similar, with larger β estimates in minimally adjusted models (adjusted for age, race, and baseline BMI); results were unchanged in models additionally adjusted for parity in women (eTable 4).

Table 3.

Average annual changes in BMI and waist circumference for young adults by long-term activity categoriesa

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure by Long-term activity category | No. | Mean change/y (95% CI) | Mean change/y (95% CI), relative to lower activity category | No. | Mean change/y (95% CI) | Mean change/y (95% CI), relative to lower activity category |

| BMIb | ||||||

| Lower | 477 | 0.20 (0.17 to 0.23) | 1 [Reference] | 475 | 0.30 (0.25 to 0.34) | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 102 | 0.14 (0.09 to 0.19) | -0.06 (-0.11 to 0.00) | 104 | 0.25 (0.15 to 0.34) | -0.05 (-0.16 to 0.05) |

| Higher | 201 | 0.15 (0.11 to 0.18) | -0.05 (-0.10 to -0.01)c | 206 | 0.17 (0.12 to 0.21) | -0.13 (-0.19 to -0.07)c |

| Inconsistent patterns | 909 | 0.20 (0.18 to 0.22) | 0.00 (-0.04 to 0.03) | 1080 | 0.25 (0.23 to 0.28) | -0.05 (-0.10 to 0.00) |

| Waist, cm | ||||||

| Lower | 477 | 0.67 (0.60 to 0.75) | 1 [Reference] | 475 | 0.67 (0.60 to 0.75) | 1 [Reference] |

| Moderate | 102 | 0.50 (0.36 to 0.64) | -0.17 (-0.33 to -0.02)c | 104 | 0.59 (0.40 to 0.79) | -0.08 (-0.29 to 0.13) |

| Higher | 201 | 0.52 (0.43 to 0.61) | -0.15 (-0.27 to -0.03)c | 206 | 0.49 (0.39 to 0.58) | -0.19 (-0.31 to -0.06)c |

| Inconsistent patterns | 909 | 0.64 (0.58 to 0.69) | -0.04 (-0.13 to 0.06) | 1080 | 0.67 (0.61 to 0.72) | -0.01 (-0.10 to 0.09) |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval

Values are adjusted for examination center, race, baseline BMI, and the following time-dependent variables: age, education, alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, and energy intake. Baseline ages for young adults are 18 to 30 years. Long-term physical activity categories are based on maintaining sex-specific baseline total activity score tertiles in at least two-thirds of follow-up examinations: lower activity, less than 340 exercise units (men) and less than 192 exercise units (women); moderate activity, 340 to 607 exercise units (men) and 192 to 397 exercise units (women); higher activity, at least 608 exercise units (men) and at least 398 exercise units (women); inconsistent patterns, all other patterns of activity.

BMI is calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Values are significantly different (P <.05) from reference group

When habitual high activity was defined as maintaining 300 exercise units over 20 years, equivalent to HHS-recommended activity levels, 36.7% of the cohort (n=1338) met this definition. Participants maintaining HHS-recommended activity levels experienced smaller annual increases in mean BMI and waist circumference compared with participants who did not after adjustment for race, baseline BMI, age, education, cigarette smoking status, alcohol use, and energy intake (Table 4). Men and women maintaining HHS-recommended activity levels gained 1.8 and 4.7 fewer kilograms, respectively over 20 years, compared with participants who did not. Patterns of association were similar, with larger β estimates in models minimally adjusted for age, race, and baseline BMI (eTable 5).

Table 4.

Average annual changes in BMI and waist circumference for young adults by HHS recommended activity levelsa

| Men | Women | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| No. | Mean change/y (95% CI) | Mean change/y (95% CI), relative to not meeting HHS recommendations | No. | Mean change/y (95% CI) | Mean change/y (95% CI), relative to not meeting HHS recommendations | |

| BMIb | ||||||

| Did not meet HHS recommendations | 799 | 0.21 (0.18 to 0.23) | 1 [Reference] | 1418 | 0.27 (0.25 to 0.30) | 1 [Reference] |

| Met HHS recommendations | 890 | 0.17 (0.15 to 0.19) | -0.03 (-0.06 to -0.01)c | 448 | 0.18 (0.15 to 0.22) | -0.09 (-0.13 to -0.05)c |

| Waist circumference, cm | ||||||

| Did not meet HHS recommendations | 799 | 0.67 (0.61 to 0.73) | 1 [Reference] | 1418 | 0.68 (0.64 to 0.73) | 1 [Reference] |

| Met HHS recommendations | 890 | 0.58 (0.53 to 0.63) | -0.08 (-0.16 to -0.01)c | 448 | 0.52 (0.44 to 0.60) | -0.17 (-0.26 to -0.07)c |

Abbreviation: BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; HHS, Health and Human Services

HHS recommends at least 150 minutes of moderate activity per week, roughly equivalent to total activity score of at least 300 exercise units. All values were adjusted for examination center, race, baseline BMI, and the following time-dependent variables: age, education, alcohol intake, cigarette smoking, and energy intake.

BMI was calculated as weight in kilograms divided by height in meters squared.

Values are significantly different (P <.05) from reference group

Comment

The primary finding of the current study is that relative to lower activity levels, maintenance of higher activity levels over 20 years was associated with smaller gains in BMI among men and women as they transitioned from young adulthood into middle age. Men and women maintaining higher activity gained 2.6 and 6.1 fewer kilograms over 20 years respectively, compared with the low-activity referent group. Weight gains in participants with moderate or inconsistent activity levels generally were not different from the low activity group. Importantly, women seemed to benefit the most from maintaining higher activity; the magnitude of weight change was more than twice as large among women compared with men. Similarly, participants who maintained the HHS-recommended 150 minutes of moderate activity per week gained significantly less weight compared with participants who did not. Relationships between activity and weight gain were not modified by race or baseline weight status. All associations were independent of factors related to activity or adiposity, including age, education, cigarette smoking status, alcohol use, and energy intake. These results suggest that maintaining higher activity levels during young adulthood may lessen weight gain as young adults transition to middle age.

Our primary finding is in agreement with several longitudinal observational studies showing an inverse association between weight gain and habitual activity.19-22 The present study demonstrates these findings even more clearly because our habitual activity categories, based on multiple measures of activity, reflect habitual activity level over time more accurately than studies characterizing habitual activity using only two time points. Importantly, our results are observed during the 20-year transition from young adulthood to middle age, where the highest risk of weight gain occurs.13

Although interventional studies of 12 months or less demonstrate weight loss and weight maintenance with 30 minutes of activity,23 their short duration could not test activity’s efficacy over many years. Furthermore, participants in these intervention studies were obese or weight-reduced at study entry, limiting application to secondary prevention of weight gain rather than primary prevention. This distinction is critical because activity levels necessary for weight loss or weight maintenance in the obese may be substantially different from the general population.24 Our results extend the application of short-term interventional study findings to a general population concerned with primary weight gain prevention over many years.

The amount of activity for weight gain prevention has been widely debated.8,24,25 Our results support findings from intervention studies suggesting that 30 minutes of activity might be sufficient.23,26,27 However, 2 observational studies have contrary findings. Lee et al. reported that 30 minutes of activity were insufficient for weight gain prevention over 13 years among middle-aged women in the Women’s Health Study.12 Among middle-aged men in the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study, DiPietro et al28 concluded that maintaining even 60 minutes of daily activity might not be sufficient to attenuate age-related weight gain. Lee and DiPietro examined weight change in middle-aged adults, which may explain the incongruent results. At older ages, higher activity levels may be necessary to overcome the well-documented age-related declines in resting metabolic rate and lean body mass.29 This hypothesis is supported by the observation from the Women’s Health Study, which shows that women younger than 55 years maintaining 30 and 60 minutes of activity had similar weight gain.

We observed greater control in weight gain among women who maintain higher activity compared with men. These sex differences could reflect reporting bias in self-reported activity or energy intake data used by CARDIA. Relationships between BMI and self-reported activity are often stronger in women who are less likely than men to overreport activity.30 Indeed, the observed stronger associations in women are consistent with other reports using self-reported activity data.16,24,30-34 Compensatory changes in energy intake may also account for sex differences in the association between activity and BMI.35-37 In the present study, men maintaining higher activity levels reported greater energy intake at all examinations compared with men with lower activity. A compensatory increase in energy intake with higher activity could explain some lessening in the association between activity and weight change observed in men. This hypothesis is highly speculative because the role of energy intake in the relationship between activity and weight change over time cannot be precisely measured from our data.

Although maintaining high activity levels helps lessen weight gain, 2 caveats of our observations should be highlighted. First, higher activity alone may not be sufficient to entirely prevent age-related weight gain. At all activity levels, men and women experienced gains in BMI and waist circumference over 20 years. Some age-related weight gain may be unavoidable in our society, as it has been observed even among a population of vigorously active runners through middle-age.38 Second, only a small proportion of adults maintain higher activity levels over several years. Our observed 11% to 12% prevalence of habitual high activity over 20 years supports interventional data that less than one-third of participants maintain high activity after 2 years.39

Our use of 7 activity scores over 20 years to create categories of habitual activity is an important strength of this study; indeed, prior longitudinal studies created habitual activity variables using only 2 measures (baseline and follow-up), regardless of the time interval between.20,22,28 Because there is no standard definition for habitual activity, activity categories were created a priori, making misclassification possible. We believe our methodology accurately identifies a group of people habitually active at high levels over 20 years; still it is possible that tertile groups did not discriminate sufficiently between high and low activity.

Our study is limited by measuring activity by self-report, which is known to overestimate activity duration and intensity. Our study is further limited by lack of detail on activity duration. As a result, we cannot translate the activity dose used to define higher activity levels into a precise exercise prescription beyond that which was previously done to estimate the activity dose equivalent to HHS activity recommendations.

In conclusion, maintaining higher levels of moderate and vigorous activity throughout young adulthood is associated with smaller gains in BMI and waist circumference during the transition from young adulthood to early middle age, particularly in women. Our results reinforce the role of physical activity in minimizing weight gain and highlight the value of incorporating and maintaining at least 30 minutes of activity into daily life throughout young adulthood.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

A.L. Hankinson had full access to all of the data in the study and takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

The design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; and preparation of the manuscript were supported by the following contracts and grants: N01-HC-95095; N01-HC-48047; N01-HC-48048; N01-HC-48049; N01-HC-48050; and R01 HL078972 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute.

Footnotes

There are no other financial disclosures.

References

- 1.Flegal KM, Carroll MD, Ogden CL, Curtin LR. Prevalence and trends in obesity among US adults, 1999-2008. Jama. 2010 Jan 20;303(3):235–241. doi: 10.1001/jama.2009.2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Visscher TL, Seidell JC. The public health impact of obesity. Annu Rev Public Health. 2001;22:355–375. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.22.1.355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Daviglus ML, Liu K, Yan LL, et al. Relation of body mass index in young adulthood and middle age to Medicare expenditures in older age. Jama. 2004 Dec 8;292(22):2743–2749. doi: 10.1001/jama.292.22.2743. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kumanyika SK, Obarzanek E, Stettler N, et al. Population-based prevention of obesity: the need for comprehensive promotion of healthful eating, physical activity, and energy balance: a scientific statement from American Heart Association Council on Epidemiology and Prevention, Interdisciplinary Committee for Prevention (formerly the expert panel on population and prevention science) Circulation. 2008 Jul 22;118(4):428–464. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.189702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fogelholm M, Kukkonen-Harjula K. Does physical activity prevent weight gain--a systematic review. Obes Rev. 2000 Oct;1(2):95–111. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2000.00016.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Haskell WL, Lee IM, Pate RR, et al. Physical activity and public health: updated recommendation for adults from the American College of Sports Medicine and the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2007 Aug 28;116(9):1081–1093. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.185649. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHO technical report series. Vol. 894. Geneva, Switzerland: 1999. Obesity: preventing and managing the global epidemic: report of a WHO consultation. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Dietary Reference Intakes for Energy, Carbohydrate, Fiber, Fat, Fatty Acids, Cholesterol, Protein, and Amino Acids (Macronutrients) Washington, D.C.: National Academies Press; 2002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Donnelly JE, Blair SN, Jakicic JM, Manore MM, Rankin JW, Smith BK. American College of Sports Medicine Position Stand. Appropriate physical activity intervention strategies for weight loss and prevention of weight regain for adults. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2009 Feb;41(2):459–471. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0b013e3181949333. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ross R, Janssen I. Physical activity, total and regional obesity: dose-response considerations. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2001 Jun;33(6 Suppl):S521–527. doi: 10.1097/00005768-200106001-00023. discussion S528-529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Physical Activity Guidelines Committee. Physical Activity Guidelines Advisory Committee Report. Washington, DC: Department of Health and Human Services; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lee IM, Djousse L, Sesso HD, Wang L, Buring JE. Physical activity and weight gain prevention. Jama. 2010 Mar 24;303(12):1173–1179. doi: 10.1001/jama.2010.312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sheehan TJ, DuBrava S, DeChello LM, Fang Z. Rates of weight change for black and white Americans over a twenty year period. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2003 Apr;27(4):498–504. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pratt M, Macera CA, Blanton C. Levels of physical activity and inactivity in children and adults in the United States: current evidence and research issues. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 1999 Nov;31(11 Suppl):S526–533. doi: 10.1097/00005768-199911001-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Friedman GD, Cutter GR, Donahue RP, et al. CARDIA: study design, recruitment, and some characteristics of the examined subjects. J Clin Epidemiol. 1988;41(11):1105–1116. doi: 10.1016/0895-4356(88)90080-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jacobs DR, Hahn LP, Haskell WL, Pirie P, Sidney S. Validity and reliability of short physical activity history: CARDIA and the Minnesota Heart Health Program. Journal of Cardiopulmonary Rehabilitation. 1989;9:448–459. doi: 10.1097/00008483-198911000-00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Parker ED, Schmitz KH, Jacobs DR, Jr, Dengel DR, Schreiner PJ. Physical activity in young adults and incident hypertension over 15 years of follow-up: the CARDIA study. Am J Public Health. 2007 Apr;97(4):703–709. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2004.055889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu K, Slattery M, Jacobs D, Jr, et al. A study of the reliability and comparative validity of the cardia dietary history. Ethn Dis. 1994 Winter;4(1):15–27. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kimm SY, Glynn NW, Obarzanek E, et al. Relation between the changes in physical activity and body-mass index during adolescence: a multicentre longitudinal study. Lancet. 2005 Jul 23-29;366(9482):301–307. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(05)66837-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sternfeld B, Wang H, Quesenberry CP, Jr, et al. Physical activity and changes in weight and waist circumference in midlife women: findings from the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation. Am J Epidemiol. 2004 Nov 1;160(9):912–922. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwh299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sherwood NE, Jeffery RW, French SA, Hannan PJ, Murray DM. Predictors of weight gain in the Pound of Prevention study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000 Apr;24(4):395–403. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Williamson DF, Madans J, Anda RF, Kleinman JC, Kahn HS, Byers T. Recreational physical activity and ten-year weight change in a US national cohort. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1993 May;17(5):279–286. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Slentz CA, Duscha BD, Johnson JL, et al. Effects of the amount of exercise on body weight, body composition, and measures of central obesity: STRRIDE--a randomized controlled study. Arch Intern Med. 2004 Jan 12;164(1):31–39. doi: 10.1001/archinte.164.1.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Saris WH, Blair SN, van Baak MA, et al. How much physical activity is enough to prevent unhealthy weight gain? Outcome of the IASO 1st Stock Conference and consensus statement. Obes Rev. 2003 May;4(2):101–114. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2003.00101.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Erlichman J, Kerbey AL, James WP. Physical activity and its impact on health outcomes. Paper 2: Prevention of unhealthy weight gain and obesity by physical activity: an analysis of the evidence. Obes Rev. 2002 Nov;3(4):273–287. doi: 10.1046/j.1467-789x.2002.00078.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.McTiernan A, Sorensen B, Irwin ML, et al. Exercise effect on weight and body fat in men and women. Obesity (Silver Spring) 2007 Jun;15(6):1496–1512. doi: 10.1038/oby.2007.178. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Gallagher KI, Napolitano M, Lang W. Effect of exercise duration and intensity on weight loss in overweight, sedentary women: a randomized trial. Jama. 2003 Sep 10;290(10):1323–1330. doi: 10.1001/jama.290.10.1323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Di Pietro L, Dziura J, Blair SN. Estimated change in physical activity level (PAL) and prediction of 5-year weight change in men: the Aerobics Center Longitudinal Study. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 Dec;28(12):1541–1547. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Vaughan L, Zurlo F, Ravussin E. Aging and energy expenditure. Am J Clin Nutr. 1991 Apr;53(4):821–825. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/53.4.821. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Ball K, Owen N, Salmon J, Bauman A, Gore CJ. Associations of physical activity with body weight and fat in men and women. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2001 Jun;25(6):914–919. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801622. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wenche DB, Holmen J, Kruger O, Midthjell K. Leisure time physical activity and change in body mass index: an 11-year follow-up study of 9357 normal weight health women 20-49 years old. J Womens Health (Larchmt) 2004 Jan-Feb;13(1):55–62. doi: 10.1089/154099904322836456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Droyvold WB, Holmen J, Midthjell K, Lydersen S. BMI change and leisure time physical activity (LTPA): an 11-y follow-up study in apparently healthy men aged 20-69 y with normal weight at baseline. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2004 Mar;28(3):410–417. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Littman AJ, Kristal AR, White E. Effects of physical activity intensity, frequency, and activity type on 10-y weight change in middle-aged men and women. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005 May;29(5):524–533. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0802886. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Gordon-Larsen P, Hou N, Sidney S, et al. Fifteen-year longitudinal trends in walking patterns and their impact on weight change. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009 Jan;89(1):19–26. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.2008.26147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Schmitz KH, Jacobs DR, Jr, Leon AS, Schreiner PJ, Sternfeld B. Physical activity and body weight: associations over ten years in the CARDIA study. Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2000 Nov;24(11):1475–1487. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Westerterp KR. Alterations in energy balance with exercise. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998 Oct;68(4):970S–974S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/68.4.970S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Westerterp KR, Goran MI. Relationship between physical activity related energy expenditure and body composition: a gender difference. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 1997 Mar;21(3):184–188. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0800385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Williams PT, Wood PD. The effects of changing exercise levels on weight and age-related weight gain. Int J Obes (Lond) 2005 Nov 29; doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0803172. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Jakicic JM, Marcus BH, Lang W, Janney C. Effect of exercise on 24-month weight loss maintenance in overweight women. Arch Intern Med. 2008 Jul 28;168(14):1550–1559. doi: 10.1001/archinte.168.14.1550. discussion 1559-1560. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.