Abstract

Background

Oxidative stress is a key element in the pathogenesis of emphysema, but oxidation of nucleic acids has been largely overlooked. The aim of this study was to investigate oxidative damage to nucleic acids in severe emphysematous lungs.

Methods

Thirteen human severe emphysematous lungs, including five with α1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), were obtained from patients receiving lung transplantation. Control lung tissue was obtained from non-COPD lungs (n = 8) and donor lungs (n = 8). DNA and RNA oxidation were investigated by immunochemistry. Morphometry (mean linear intercept [Lm] and CT scan) and immunostaining for CD68 and neutrophil elastase also were performed.

Results

Nucleic acid oxidation was increased in alveolar wall cells in emphysematous lungs compared to non-COPD and donor lungs (p < 0.01). In emphysematous lungs, oxidative damage to nucleic acids in alveolar wall cells was increased in the more severe emphysematous areas assessed by histology (Lm, > 0.5 mm; p < 0.05) and CT scan (< −950 Hounsfield units; p < 0.05). Compared to classic emphysema, AATD lungs exhibited higher levels of nucleic acid oxidation in macrophages (p < 0.05) and airway epithelial cells (p < 0.01). Pretreatments with DNase and RNase demonstrated that RNA oxidation was more prevalent than DNA oxidation in alveolar wall cells.

Conclusions

We demonstrated for the first time that nucleic acids, especially RNA, are oxidized in human emphysematous lungs. The correlation between the levels of oxidative damage to nucleic acids in alveolar wall cells and the severity of emphysema suggest a potential role in the pathogenesis of emphysema.

Keywords: α1-antitrypsin deficiency, emphysema, nucleic acids, oxidative stress, RNA

Pulmonary emphysema is defined as a pathologic process of alveolar destruction with airspace enlargement not associated with a significant amount of fibrosis.1,2 Cigarette smoke outweighs any other etiologic factor, but many aspects of the pathobiology of emphysema remain unclear.2–5 Oxidative stress plays a key role in the pathogenesis of emphysema.6–10 Excess oxidants are generated either exogenously from cigarette smoke or air pollutants or endogenously from activated neutrophils and macrophages releasing reactive oxygen species (ROS). Antioxidant defenses regulate ROS levels, but an oxidant-to-antioxidant imbalance leads to oxidative stress in COPD.11 ROS inactivates antiproteases, regulates cell proliferation, induces apoptosis, and modulates the immune system through activation of transcription factors. ROS also induces direct damage to various macromolecules, such as proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids.11–13 Whereas lipid peroxidation and protein oxidation have been shown to be elevated in COPD lungs,14,15 the oxidation of nucleic acids has been less well studied. In nucleic acids, ROS can oxidize guanine to produce 8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine (8OHdG) in DNA and 8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine (8OHG) in RNA.16 Surprisingly, the extent and distribution of oxidative damage to nucleic acids in the lung, especially in alveoli, have never been investigated in human emphysema. Moreover, whereas RNA oxidation plays a key role in various neurodegenerative diseases,17,18 the question of whether RNA oxidation could be involved in emphysema pathogenesis never has been addressed. The aim of the present study is to investigate the extent and localization of oxidative damage to nucleic acids in severe emphysematous lungs.

Materials and Methods

Patients

Thirteen severe emphysematous lungs, including 5 with α1-antitrypsin deficiency (AATD), were obtained from patients receiving lung transplantation. Control lung tissue was obtained from non-COPD lungs (n = 8) and donor lungs (n = 8). COPD diagnosis was established on the basis of the Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease consensus statement.19 This study was reviewed and approved by the Washington University School of Medicine Human Studies Committee. An informed written consent was obtained for each patient.

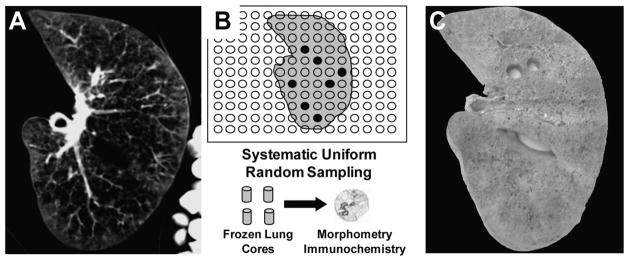

Lung Processing, Imaging, and Sampling

Freshly explanted emphysematous lungs were rapidly frozen over liquid nitrogen while inflated as described elsewhere,20 and radiograph CT of the frozen lungs was performed (Fig 1, left, A). Lungs were cut into 2-cm-thick transverse slices in the same plane as the CT scan and sampled using a 13-mm diameter punch following a systematic uniform random sampling plan (Fig 1, center, B). Photos of sampled lung slices were used to match samples to CT images (Fig 1, right, C). Six cores per emphysematous lung were randomly chosen and kept frozen until use. Lung tissue from donor lungs and non-COPD lungs obtained from resection for lung cancer (avoiding areas affected by tumor) were kept frozen and processed in the same manner as the cores from the emphysematous lungs.

Figure 1.

Processing and sampling of human lung tissue. Left, A: 10 mm-thickness CT sections of a frozen lung. Center, B: random sampling plan for coring lung slabs in 13-mm diameter cores, which were used for morphometry and immunochemistry. Right, C: corresponding picture of the slice with two cores sampled.

Immunochemistry

Serial sections of 5 μm in thickness were cut from paraformaldehyde-fixed (24 h), paraffin-embedded specimens. Immunohistochemical staining with an immunostaining kit (Vectastain; Vector Laboratories; Burlingame, CA) used the following primary antibodies: 8OHG/8OHdG (1:200; QED Bioscience; San Diego, CA), specific for DNA and RNA oxidation; CD68 (1:200, KP1; Dako; Kyoto, Japan), specific for macrophages; and neutrophil elastase (1:100, NP57, QED Bioscience), specific for neutrophils or isotype-matched nonimmune IgG as negative controls. Counterstaining was performed using nuclear fast red (American Master Tech Scientific; Lodi, CA). For quantification, 10 randomly selected, nonoverlapping fields were captured. The total alveolar wall cells, luminal cells, or airway cells and the number positive for 8OHG/8OHdG were manually counted while blinded to sample identity. The percentage of 8OHG/ 8OHdG-positive cells relative to the total number alveolar wall cells, luminal cells, or airway cells were calculated for each core. CD68 and neutrophil elastase expression were determined using image processing digital software (Image-Pro Plus; Media Cybernetics; Bethesda, MD) as previously described.21

In some experiments, serial tissue sections were incubated with DNase-free RNase A (10 μg/L) [Sigma; St. Louis, MO], RNase-free DNase I (2 U/μL) [Sigma], or both for 60 min at 37°C before incubation with the anti-8OHG/8OHdG antibody, as previously described.22,23 The specificities of DNase and RNase pretreatments were confirmed using the methyl green-pyronin method that differentially stains DNA and RNA, as previously described.24 RNase pretreatment removed staining for RNA, with only remaining nuclei stained blue to indicate DNA resistant to RNase, whereas DNase pretreatment removed all nuclear staining, leaving only red cytoplasmic staining to indicate RNA resistant to DNase (not shown).

Morphologic Analysis

The mean linear intercept (Lm) was determined for each core obtained from emphysematous lungs using hematoxylineosin (Sigma) stained slides and analyzed by the image processing digital software, as previously described.20 The mean radiograph attenuation, expressed in Hounsfield units (HU), also was determined in CT sections corresponding to each core by a separate image processing program (ImageJ; available at: http://rsb.info.nih.gov/ij) [Fig 1, left, A, and right, C].

Statistical Analysis

The data are expressed as the mean ± SD. A Mann–Whitney test was used to compare groups, and Spearman rank correlation was used to test for correlations between variables, with a p < 0.05 considered significant.

Results

Patients

Tables 1 and 2 show the characteristics of the patients with emphysematous lungs. Patients with AATD had a lower number of pack-years than seen in classic emphysema (CE) [AATD, 15 ± 9 pack-years; CE, 46 ± 14 pack-years; p < 0.01] and were younger (AATD, 46 ± 11 years; CE, 55 ± 5 years; p < 0.05). A whole donor lung not used for transplantation (because of a last-minute surgical change) was obtained from a 27-year-old man who was an occasional smoker (< 2 pack-years). Lung pieces of donor lungs resected to adjust the lung to an appropriate size for transplantation were obtained from seven patients (gender, five men and two women; age, 24 ± 14 years; smoking habits, four never-smokers, two current smokers [3 and 8 pack-years, respectively], and one undetermined). Lung tissue also was obtained from eight patients without COPD who were treated with surgical resection for lung cancer (gender, five men and two women; age, 64 ± 12 years; FEV1, 101 ± 6%, FEV1/FVC, 75 ± 7%). All patients without COPD were current smokers (n = 3) or former smokers (n = 5), with an average of 48 ± 28 pack-years.

Table 1.

Clinical Characteristics of the Patients With Severe Emphysema*

| Patient No. | Age, yr | Gender | Smoking, Pack-yr | Quit Smoking, yr | AATD | FEV1 | FVC | FEV1/FVC Ratio | TLC | RV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 60 | F | 50 | 3 | No | 18 | 47 | 32 | 110 | 224 |

| 2 | 59 | F | 37 | 10 | No | 13 | 39 | 26 | 187 | 437 |

| 3 | 47 | F | 50 | 3 | No | 16 | 45 | 30 | 103 | 234 |

| 4 | 54 | F | 57 | 1 | No | 16 | 53 | 25 | 174 | 363 |

| 5 | 55 | F | 55 | 12 | No | 26 | 74 | 29 | 147 | 287 |

| 6 | 41 | M | 15 | 6 | Yes | 9 | 23 | 34 | 132 | 411 |

| 7 | 64 | F | 25 | 20 | Yes | 25 | 54 | 36 | 139 | 263 |

| 8 | 47 | M | 24 | 8 | Yes | 21 | 63 | 27 | 146 | 316 |

| 9 | 57 | F | 25 | 9 | No | 15 | 56 | 22 | 170 | 331 |

| 10 | 44 | M | 3 | 10 | Yes | 21 | 64 | 27 | 142 | 294 |

| 11 | 36 | F | 10 | 4 | Yes | 17 | 59 | 25 | 163 | 416 |

| 12 | 61 | F | 64 | 5 | No | 22 | 62 | 29 | 121 | 214 |

| 13 | 62 | M | 30 | 16 | No | 18 | 58 | 24 | 131 | 282 |

Values are given as percent predicted, unless otherwise indicated. TLC = total lung capacity; RV = residual volume; F = female; M = male.

Table 2.

Arterial Blood Gas and Treatments of the Patients With Severe Emphysema

| Patient No. | PaO2, mm Hg | PaCO2, mm Hg | pH | Oral Corticosteroids, mg/d | Inhaled Corticosteroids | Inhaled Anticholinergics | Inhaled Long-Acting β-Agonists | Inhaled Short-Acting β-Agonists | O2 Therapy at Rest, L/min |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 51 | 65 | 7.37 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 1.5 |

| 2 | 52 | 67 | 7.34 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| 3 | 46 | 46 | 7.37 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| 4 | 80 | 42 | 7.40 | 7.5 | No | Yes | No | Yes | 0 |

| 5 | 64 | 52 | 7.36 | No | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| 6 | 50 | 74 | 7.34 | 10 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 |

| 7 | 46 | 48 | 7.40 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| 8 | 58 | 43 | 7.41 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | 3 |

| 9 | 51 | 49 | 7.40 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 2 |

| 10 | 60 | 37 | 7.43 | 10 | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 2 |

| 11 | 68 | 41 | 7.37 | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | 2 |

| 12 | 58 | 44 | 7.44 | 20 | No | Yes | No | Yes | 3 |

| 13 | 73 | 40 | 7.41 | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | 0 |

Correlation of Nucleic Acid Oxidation in Alveolar Wall Cells With Extent of Emphysema

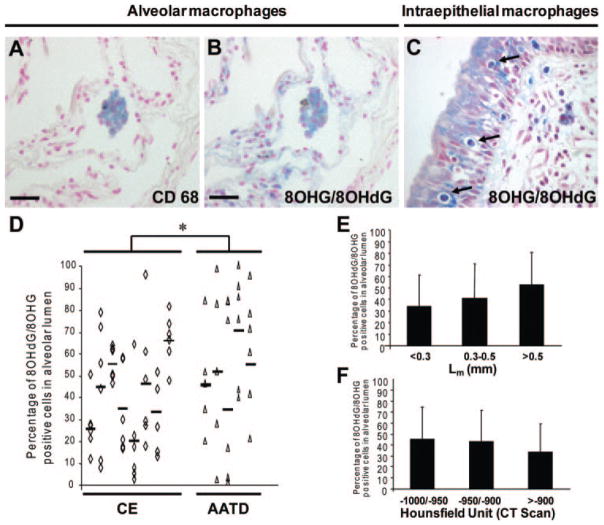

Cells staining for 8OHG/8OHdG were observed in the alveolar wall of lungs with severe emphysema in CE (Fig 2, top left, A, and top middle, B) and AATD (Fig 2, center left, C, and center middle, D), whereas low levels of 8OHG/8OHdG staining were observed in donor lungs (Fig 2, bottom left, E) and non-COPD lungs (Fig 2, bottom middle, F). The number of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive alveolar wall cells was highly variable between cores from the same lung in both CE and AATD, indicating heterogeneity in nucleic acid oxidation in emphysematous lungs (Fig 2, right, G). No difference in the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive alveolar wall cells was found between CE and AATD (CE, 29 ± 14%; AATD, 31 ± 19%; not significant). By contrast, the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive alveolar wall cells was lower in donor lungs (7 ± 4%; p < 0.01) and non-COPD lungs (5 ± 3%; p < 0.01). Interestingly, both current smokers and former smokers exhibited low levels of nucleic acid oxidation in the non-COPD group.

Figure 2.

Oxidative damage to nucleic acids in alveolar wall cells in human emphysematous lung. Top left, A, and top middle, B: immunostaining for 8OHG/8OHdG, a specific antibody detecting RNA and DNA oxidation, demonstrated positive cells (blue) in alveolar wall cells of emphysematous lungs from patients with CE (top left, A: original ×10; top middle, B: original ×40). Center left, C, and center middle, D: immunostaining for 8OHG/8OHdG demonstrated positive cells (blue) in alveolar wall cells of emphysematous lungs from patients with AATD (center left, C: original ×20; center middle, D: original ×40). Note the predominant cytoplasmic localization of 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining in alveolar wall cells (arrows). Bottom left, E, and bottom middle, F: by contrast, very low levels of 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining is seen in donor and non-COPD lungs, respectively (bottom left, E: original ×10; bottom middle, F: original ×40). Right, G: percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive alveolar cells in six cores per patient obtained from eight CE lungs (open rhombus) and five AATD lungs (open triangle) and controls in four cores obtained from one whole donor lung (open circle), seven wedge resections from seven donor lungs (solid circle), and eight non-COPD lungs (solid triangle). Bars represent the mean for each patient with CE and AATD. Scale bars = 50 μm; NS = not significant; * = p < 0.01.

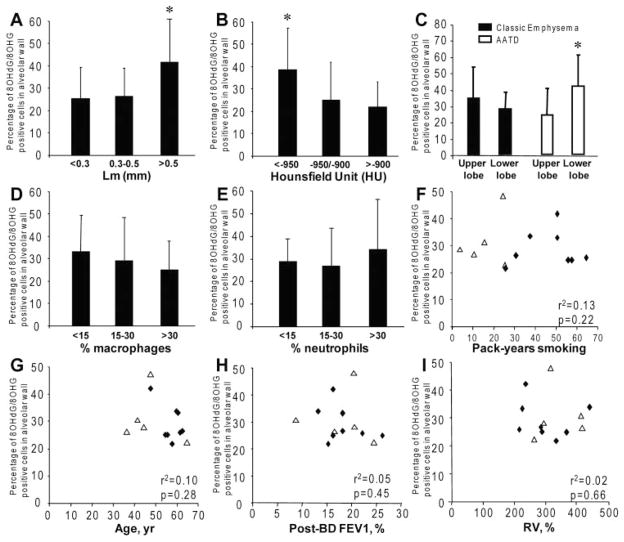

The percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive alveolar wall cells was higher in areas with greater emphysema severity as assessed by histology (Lm, > 0.5 mm; p < 0.05) [Fig 3, top left, A] and CT scan (< −950 HU; p < 0.05) [Fig 3, top middle, B]. The percentage of cells positive for 8OHG/8OHdG was significantly higher in the lower lobe of AATD lungs (p < 0.01), whereas it was higher in the upper lobe in CE lungs (Fig 3, top right, C). As macrophages and neutrophils release ROS, we investigated the relationships between 8OHG/8OHdG in alveolar wall cells and the infiltration by macrophages and neutrophils. No correlation was found between the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells and macrophage (Fig 3, center left, D) or neutrophil (Fig 3, center middle, E) infiltration. No correlation was found between the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive alveolar wall cells of patients with COPD and pack-years (Fig 3, center right, F), age (Fig 3, bottom left, G), airflow limitation (postbronchodilator FEV1) [Fig 3, bottom middle, H], lung hyperinflation (residual volume) [Fig 3, bottom right, I], and total lung capacity or medical treatments (not shown).

Figure 3.

Relationships between oxidative damage to nucleic acids in alveolar wall cells and morphometry, cellular infiltration, smoking, age, and lung function in severe emphysema. Top left, A, and top middle, B: association between the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells in alveolar wall and the morphometry assessed by histology (Lm > 0.5 mm; p < 0.05) and CT scan (< −950 HU; p < 0.05), respectively. Top right, C: distribution of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells in upper and lower lobes in CE lungs (black bars) and AATD lungs (white bars). Center left, D, and center middle, E: absence of association between 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining and infiltration by macrophages and neutrophils, respectively. Center right, F, bottom left, G, bottom middle, H, and bottom right, I: absence of correlation between the mean percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells in alveolar wall cells and pack-years, age, and functional parameters postbronchodilator (post-BD) FEV1, and residual volume (RV), respectively, in eight CE lungs (open triangle) and five AATD lungs (solid rhombus). All values are presented as the mean ± SD. * = p < 0.05.

Macrophages and Airway Epithelial Cells Exhibit Higher Levels of Nucleic Acid Oxidation in AATD

In CE and AATD lungs, 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells were observed in the alveolar lumen. Most of the cells were macrophages, as shown by double staining in serial sections with CD68 and 8OHG/ 8OHdG (Fig 4, top left, A, and top middle, B). We also found intraepithelial macrophages stained for 8OHG/8OHdG (Fig 4, top right, C). Neutrophils were negative for 8OHG/8OHdG (not shown). Blood vessels were mainly negative for 8OHG/ 8OHdG (not shown). The percentage of 8OHG/ 8OHdG-positive cells in the alveolar lumen was slightly higher in AATD lungs than in CE lungs (AATD, 55 ± 30%; CE, 41 ± 23%; p = 0.03) [Fig 4, bottom left, D]. The percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells in the alveolar lumen was not correlated with the local-regional severity of emphysema (Fig 4, bottom right top, E, and bottom right bottom, F). The number of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells in the alveolar lumen was lower in donor lungs (8 ± 8%; p < 0.01) and non-COPD lungs (5 ± 4%; p < 0.01) compared to AATD lungs.

Figure 4.

Oxidative damage to nucleic acids in macrophages in severe emphysema. Top left, A, and top middle, B: immunostaining on serial lung tissue sections for CD68 (blue) [original ×20], and 8OHG/8OHdG (blue) [original ×20], respectively, showing colocalization in the alveolar lumen. Top right, C: evidence for intraepithelial macrophages (arrows) in airway epithelium (original ×40). Bottom left, D: comparison of the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells in alveolar lumen in six cores per patient obtained from eight CE lungs and five AATD lungs. Bottom right top, E, and bottom right bottom, F: Relationship between the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells in the alveolar lumen and the morphometry assessed by histology (Lm) and CT scan (HU), respectively. Scale bars = 50 μm. All values are presented as the mean ± SD.

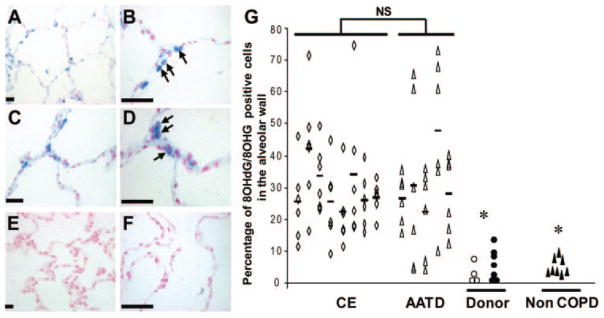

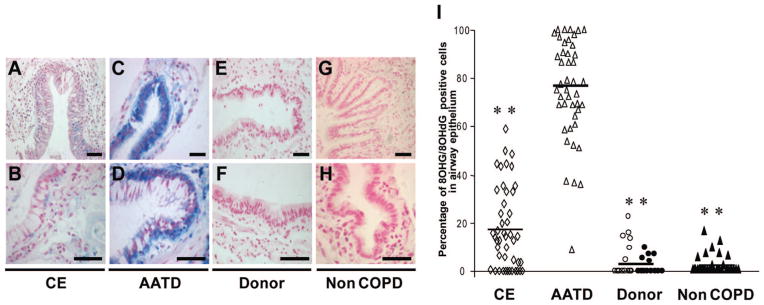

High levels of 8OHG/8OhdG-positive cells were detected in the large and small airways of CE lungs (Fig 5, top left, A, and bottom left, B) and AATD lungs (Fig 5, top middle left, C, and bottom middle left, D), whereas low levels of 8OHG/8OHdG staining was found in donor lungs (Fig 5, top middle right, E, and bottom middle right, F) and non-COPD lungs (Fig 5, top right, G, and bottom right, H). Airway epithelial cells from AATD lungs exhibited higher levels of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells compared to CE lungs (AATD, 74 < 21%; CE, 17 ± 16%; p < 0.01) [Fig 5, right, I]. The number of 8OHG/ 8OHdG-positive cells in airway epithelium were lower in donor lungs (4 ± 6%; p < 0.01) and non-COPD lungs (3 ± 3%; p < 0.01) compared to A1ATD lungs.

Figure 5.

Oxidative damage to nucleic acids in airway epithelial cells. Top left, A, and bottom left, B: 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining (blue) in airway epithelial cells in CE lungs. Top middle left, C, and bottom middle left, D: 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining (blue) in airway epithelial cells in AATD lungs. Top middle right, E, and bottom middle right, F: 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining (blue) in airway epithelial cells in donor lungs. Top right, G, and bottom right, H: 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining (blue) in airway epithelial cells in non-COPD lungs. Right, I: comparison of the percentage of 8OHG/8OHdG-positive cells in individual airway sections from CE lungs (open rhombus) [n = 46], AATD lungs (open triangle) [n = 44], donor lungs (open circle, cores from one lung not used for transplantation; solid circle, wedge resections from seven donors) [n = 27], and non-COPD lungs (n = 36). Scale bars = 50 μm ** = p < 0.01. Top row: original ×10; bottom row: original ×20.

Evidence for RNA Oxidation

The intracellular localization of the 8OHG/ 8OHdG staining both in the nucleus and in the cytoplasm suggests that both DNA and RNA could be oxidized. To investigate whether DNA, RNA, or both are oxidized, we performed pretreatments with DNase-free RNase, RNase-free DNase, or both before 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining. Compared to untreated serial sections of lung tissue (Fig 6, top left, A), RNase strongly decreased 8OHG/8OHdG staining (Fig 6, top middle left, B), whereas DNase had less effects (Fig 6, top middle right, C). Higher magnification analysis clearly demonstrated that 8OHG/8OHdG staining was mainly cytoplasmic in alveolar wall cells (Fig 6, center left, E), but some cells exhibited both nuclear and cytoplasmic staining (Fig 6, bottom left, I). RNase pretreatment dramatically decreased 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining (Fig 6, center middle left, F), but some alveolar wall cells exhibited nuclear staining (Fig 6, bottom middle left, J), suggesting that some cells exhibit not only RNA, but also DNA oxidation. DNase pretreatment showed a prominent cytoplasmic localization of 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining (Fig 6, center middle right, G, and bottom middle right, K), suggesting strong RNA oxidation in these cells. RNase and DNase combined induced complete inhibition of 8OHG/8OHdG staining, showing the selectivity of the staining for nucleic acids (Fig 6, top right, D, center right, H, and bottom right, L). Together, these data suggest that RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of alveolar wall cells in emphysema but that DNA oxidation also occurs in some alveolar wall cells. Similar results were obtained in CE and AATD lungs.

Figure 6.

Effects of pretreatments with RNase and DNase on 8OHG/8OHdG immunostaining. Top left, A, center left, E, and bottom left, I: untreated serial sections of lung tissue. Top middle left, B, center middle left, F, and bottom middle left, J: serial sections of lung tissue pretreated with RNase before immunostaining with 8OHG/8OHdG (blue). Top middle right, C, center middle right, G, and bottom middle right, K: serial sections of lung tissue pretreated with DNase before immunostaining with 8OHG/8OHdG (blue). Top right, D, center right, H, and bottom right, L: serial sections of lung tissue pretreated with both RNase and DNase before immunostaining with 8OHG/8OHdG (blue). Representative sections are from severe emphysematous lungs. Scale bars = 10 μm. Top left, A, to top right, D: original ×10. Center left, E, to bottom right, L: ×100.

Discussion

We provide for the first time compelling evidence that nucleic acid oxidation of alveolar wall cells is a prominent feature in severe emphysema. More importantly, we demonstrate that nucleic acid oxidation in alveolar wall cells is highly variable and correlates with the local-regional severity of emphysema assessed by histology and CT density. We also show a higher level of oxidative damage to nucleic acids in macrophages and airway epithelial cells in AATD lungs. Interestingly, we demonstrate that RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of alveolar wall cells in severe emphysema compared to normal alveolar tissue.

The high sensitivity and specificity of the antibody to 8OHG/8OHdG used in this study has been well validated25–28 and enabled us to perform an in situ experimental approach that both localizes and quantifies oxidative damage to nucleic acids by immuno-chemistry. Our systematic uniform random sampling process of the lung provides tissue from different areas with various degrees of emphysema, offering the unique opportunity to investigate regional distribution of oxidative damage to nucleic acids and its correlation with emphysema severity. Our findings that nucleic acid oxidation is variable in the lung and correlates with the local-regional severity of emphysema reinforce that the pathogenesis of emphysema should be viewed like a nonuniformly distributed dysregulated process.29

Although it is becoming accepted that oxidative damage is part of the pathogenesis of emphysema, oxidative damage to nucleic acids has been largely overlooked in emphysema. DNA oxidation promotes microsatellite instability, inhibits methylation, and accelerates telomere shortening,16,30 but a large number of DNA-repair processes protect against its deleterious consequences.16,30 DNA oxidation is elevated in bronchiolar and alveolar type II cells of mice exposed to short-term cigarette smoke.31,32 However, after repeated exposure, DNA oxidation significantly decreases.32 Mice deficient in nuclear factor erythroid-2 like 2 (Nrf2), a transcription factor regulating antioxidant genes, exposed to long-term cigarette smoke are more susceptible to emphysema and exhibit elevated levels of DNA oxidation in alveolar wall cells.33 We have demonstrated that Nrf2 is up-regulated in the airway epithelium after cigarette smoke exposure.34 Interestingly, we did not detect significant terminal deoxynucleotidyl transferase-mediated deoxy-uridine triphosphate-biotin nick end labeling staining in human lung tissue, even in areas with high levels of nucleic acid oxidation (not shown). Together, these results suggest that DNA oxidation is increased by oxidants in cigarette smoke but that antioxidant systems, such as those regulated by the Nrf2 pathway, counteract and protect DNA from sustained oxidation.

An important finding of our study is that RNA is oxidized in alveolar wall cells in severe emphysema. Until recently, RNA oxidation has not received as much interest as DNA oxidation; however, it is likely that RNA could have enhanced susceptibility for oxidative attack because of its widespread cytosolic distribution, single-stranded structure, absence of protective histones, and lack of an advanced repair mechanism.17,18,30 RNA oxidation is associated with nonneo-plastic pathologies, including neurodegenerative, cardiovascular, and autoimmune diseases.16 RNA oxidation also is increased in affected neurons in neuro-degenerative diseases, such as Alzheimer disease and Parkinson disease.17,18,22,23,30,35 Atherosclerotic plaques exhibit high levels of RNA oxidation.36,37 Interestingly, in neurodegenerative diseases, messenger RNA oxidation affects specific transcripts27 and induces translation errors.38 Hydrogen peroxide causes more RNA than DNA oxidation in human A549 lung epithelial cells,39 suggesting higher susceptibility of RNA to oxidative stress in the alveolar epithelium. In COPD, enhanced oxidative stress has been demonstrated, and RNA and DNA could be modified by this stress. We believe that our findings that RNA is oxidized in emphysematous lungs opens a novel and largely overlooked event in the pathogenesis of emphysema. However, whether oxidative damage to RNA is a marker of oxidative stress or a critical step in the pathogenesis of emphysema remains to be evaluated.

Another important finding of our study is that alveolar macrophages and airway epithelial cells in AATD lungs exhibit higher levels of oxidative damage to nucleic acids than in CE lungs. AATD is an autosomal recessive disease that affects the SERPINA1 gene, which encodes the AAT protein. Disease manifestation is associated with null variants or genotypes, resulting in impaired gene expression, translation, or protein synthesis.40 – 44 The majority of patients with severe lung or liver disease are homozygous for the allele Z or S (ZZ or SS) phenotype or heterozygous for both (ZS). These mutations lead to a protein conformational change that alters the folding pathway of AAT, resulting in diminished serum AAT levels and protein aggregation and accumulation in the endoplasmic reticulum.45 This accumulation can induce intracellular responses, such as activation of transcription factors, induction of apoptosis, and enhancement of oxidative stress.46,47 AAT is mainly synthesized and secreted by hepatocytes, but synthesis has been demonstrated in lung macrophages and bronchial epithelial cells.47 Our results suggest that oxidative stress induced by mutant AAT retained in the endoplasmic reticulum48 could partly explain our findings of higher nucleic acid oxidation in macrophages and airway epithelial cells. However, the direct involvement of the mutant AAT in the oxidation of nucleic acids remains to be demonstrated. Moreover, the consequences of nucleic acid oxidation in macrophages and airway epithelial cells remain to be evaluated. Nevertheless, our findings could open a new paradigm in the pathogenesis of airway disease and emphysema related to AATD.

Conclusions

These studies provide compelling evidence of oxidative damage to nucleic acids, especially RNA, in alveolar wall cells in severe emphysema. The correlation between nucleic acid oxidation in alveolar wall cells and the severity of emphysema suggests a role for nucleic acid oxidation in the pathophysiology of emphysema. We believe that the current results open a novel and largely overlooked field that could better our understanding of the complex pathogenesis of emphysema. Further investigations are needed to elucidate the role of nucleic acid oxidation, especially RNA oxidation, in the pathogenesis emphysema.

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by National Institutes of Health grant P50HL084922. Dr. Deslee received grants for postdoctoral training from Region Champagne-Ardenne, University and CHU of Reims, ARAIRCHAR, College des Professeurs de Pneumologie and AstraZeneca.

Abbreviations

- AATD

α1-antitrypsin deficiency

- CE

classic emphysema

- HU

Hounsfield units

- Lm

mean linear intercept

- Nrf2

nuclear factor erythroid-2 like 2

- 8OHdG

8-oxo-7,8-dihydro-2′-deoxyguanosine

- 8OHG

8-oxo-7,8-dihydroguanosine

- ROS

reactive oxygen species

Footnotes

No conflict of interest exists for any of the authors.

Reproduction of this article is prohibited without written permission from the American College of Chest Physicians (www.chestjournal.org/misc/reprints.shtml).

References

- 1.Snider GL. Pathogenesis and terminology of emphysema. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1994;149:1382–1383. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.149.5.8173782. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Taraseviciene-Stewart L, Voelkel NF. Molecular pathogenesis of emphysema. J Clin Invest. 2008;118:394–402. doi: 10.1172/JCI31811. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yoshida T, Tuder RM. Pathobiology of cigarette smoke-induced chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Physiol Rev. 2007;87:1047–1082. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00048.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wright JL, Churg A. Current concepts in mechanisms of emphysema. Toxicol Pathol. 2007;35:111–115. doi: 10.1080/01926230601059951. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tuder RM, Yoshida T, Arap W, et al. State of the art: cellular and molecular mechanisms of alveolar destruction in emphysema: an evolutionary perspective. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:503–510. doi: 10.1513/pats.200603-054MS. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Isik B, Ceylan A, Isik R. Oxidative stress in smokers and non-smokers. Inhal Toxicol. 2007;19:767–769. doi: 10.1080/08958370701401418. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Pinho RA, Chiesa D, Mezzomo KM, et al. Oxidative stress in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease patients submitted to a rehabilitation program. Respir Med. 2007;101:1830–1835. doi: 10.1016/j.rmed.2007.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rahman I. Oxidative stress in pathogenesis of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: cellular and molecular mechanisms. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2005;43:167–188. doi: 10.1385/CBB:43:1:167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rahman I. The role of oxidative stress in the pathogenesis of COPD: implications for therapy. Treat Respir Med. 2005;4:175–200. doi: 10.2165/00151829-200504030-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rahman I, Adcock IM. Oxidative stress and redox regulation of lung inflammation in COPD. Eur Respir J. 2006;28:219–242. doi: 10.1183/09031936.06.00053805. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Rahman I, Biswas SK, Kode A. Oxidant and antioxidant balance in the airways and airway diseases. Eur J Pharmacol. 2006;533:222–239. doi: 10.1016/j.ejphar.2005.12.087. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.MacNee W. Pulmonary and systemic oxidant/antioxidant imbalance in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2005;2:50–60. doi: 10.1513/pats.200411-056SF. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.MacNee W. Oxidants and COPD. Curr Drug Targets Inflamm Allergy. 2005;4:627–641. doi: 10.2174/156801005774912815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Petruzzelli S, Puntoni R, Mimotti P, et al. Plasma 3-nitrotyrosine in cigarette smokers. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 1997;156:1902–1907. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.156.6.9702075. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman I, van Schadewijk AA, Crowther AJ, et al. 4-Hydroxy-2-nonenal, a specific lipid peroxidation product, is elevated in lungs of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2002;166:490–495. doi: 10.1164/rccm.2110101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Evans MD, Dizdaroglu M, Cooke MS. Oxidative DNA damage and disease: induction, repair and significance. Mutat Res. 2004;567:1–61. doi: 10.1016/j.mrrev.2003.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nunomura A, Honda K, Takeda A, et al. Oxidative damage to RNA in neurodegenerative diseases. J Biomed Biotechnol. 2006;2006:82323. doi: 10.1155/JBB/2006/82323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nunomura A, Moreira PI, Takeda A, et al. Oxidative RNA damage and neurodegeneration. Curr Med Chem. 2007;14:2968–2975. doi: 10.2174/092986707782794078. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pauwels RA, Buist AS, Calverley PM, et al. Global strategy for the diagnosis, management, and prevention of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease: NHLBI/WHO Global Initiative for Chronic Obstructive Lung Disease (GOLD) Workshop summary. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2001;163:1256–1276. doi: 10.1164/ajrccm.163.5.2101039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Woods JC, Choong CK, Yablonskiy DA, et al. Hyperpolarized 3He diffusion MRI and histology in pulmonary emphysema. Magn Reson Med. 2006;56:1293–1300. doi: 10.1002/mrm.21076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Andersson J, Samarina A, Fink J, et al. Impaired expression of perforin and granulysin in CD8+ T cells at the site of infection in human chronic pulmonary tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2007;75:5210–5222. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00624-07. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang J, Perry G, Smith MA, et al. Parkinson’s disease is associated with oxidative damage to cytoplasmic DNA and RNA in substantia nigra neurons. Am J Pathol. 1999;154:1423–1429. doi: 10.1016/S0002-9440(10)65396-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Nunomura A, Chiba S, Kosaka K, et al. Neuronal RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of dementia with Lewy bodies. Neuroreport. 2002;13:2035–2039. doi: 10.1097/00001756-200211150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Nunomura A, Perry G, Aliev G, et al. Oxidative damage is the earliest event in Alzheimer disease. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol. 2001;60:759–767. doi: 10.1093/jnen/60.8.759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shan X, Lin CL. Quantification of oxidized RNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Aging. 2006;27:657–662. doi: 10.1016/j.neurobiolaging.2005.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ding Q, Dimayuga E, Markesbery WR, et al. Proteasome inhibition increases DNA and RNA oxidation in astrocyte and neuron cultures. J Neurochem. 2004;91:1211–1218. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2004.02802.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Shan X, Tashiro H, Lin CL. The identification and characterization of oxidized RNAs in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 2003;23:4913–4921. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.23-12-04913.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunomura A, Perry G, Pappolla MA, et al. RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of vulnerable neurons in Alzheimer’s disease. J Neurosci. 1999;19:1959–1964. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.19-06-01959.1999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Tuder RM, Yoshida T, Fijalkowka I, et al. Role of lung maintenance program in the heterogeneity of lung destruction in emphysema. Proc Am Thorac Soc. 2006;3:673–679. doi: 10.1513/pats.200605-124SF. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Evans MD, Cooke MS. Factors contributing to the outcome of oxidative damage to nucleic acids. Bioessays. 2004;26:533–542. doi: 10.1002/bies.20027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Aoshiba K, Koinuma M, Yokohori N, et al. Immunohisto-chemical evaluation of oxidative stress in murine lungs after cigarette smoke exposure. Inhal Toxicol. 2003;15:1029–1038. doi: 10.1080/08958370390226431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Betsuyaku T, Hamamura I, Hata J, et al. Bronchiolar chemokine expression is different after single versus repeated cigarette smoke exposure. Respir Res. 2008;9:7. doi: 10.1186/1465-9921-9-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rangasamy T, Cho CY, Thimmulappa RK, et al. Genetic ablation of Nrf2 enhances susceptibility to cigarette smoke-induced emphysema in mice. J Clin Invest. 2004;114:1248–1259. doi: 10.1172/JCI21146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Adair-Kirk TL, Atkinson JJ, Griffin GL, et al. Distal airways in mice exposed to cigarette smoke: Nrf2-regulated genes are increased in Clara cells. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2008;39:400–411. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2007-0295OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nunomura A, Chiba S, Lippa CF, et al. Neuronal RNA oxidation is a prominent feature of familial Alzheimer’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2004;17:108–113. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2004.06.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinet W, de Meyer GR, Herman AG, et al. Reactive oxygen species induce RNA damage in human atherosclerosis. Eur J Clin Invest. 2004;34:323–327. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2362.2004.01343.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Martinet W, De Meyer GR, Herman AG, et al. RNA damage in human atherosclerosis: pathophysiological significance and implications for gene expression studies. RNA Biol. 2005;2:4–7. doi: 10.4161/rna.2.1.1430. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Tanaka M, Chock PB, Stadtman ER. Oxidized messenger RNA induces translation errors. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007;104:66–71. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0609737104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hofer T, Badouard C, Bajak E, et al. Hydrogen peroxide causes greater oxidation in cellular RNA than in DNA. Biol Chem. 2005;386:333–337. doi: 10.1515/BC.2005.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Greene CM, Miller SD, Carroll T, et al. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: a conformational disease associated with lung and liver manifestations. J Inherit Metab Dis. 2008;31:21–34. doi: 10.1007/s10545-007-0748-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.de Serres FJ, Blanco I, Fernandez-Bustillo E. PI S and PI Z alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency worldwide: a review of existing genetic epidemiological data. Monaldi Arch Chest Dis. 2007;67:184–208. doi: 10.4081/monaldi.2007.476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Kohnlein T, Welte T. Alpha-1 antitrypsin deficiency: pathogenesis, clinical presentation, diagnosis, and treatment. Am J Med. 2008;121:3–9. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2007.07.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Stolk J, Seersholm N, Kalsheker N. Alpha1-antitrypsin deficiency: current perspective on research, diagnosis, and management. Int J Chron Obstruct Pulmon Dis. 2006;1:151–160. doi: 10.2147/copd.2006.1.2.151. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Perlmutter DH, Brodsky JL, Balistreri WF, et al. Molecular pathogenesis of α1-antitrypsin deficiency-associated liver disease: a meeting review. Hepatology. 2007;45:1313–1323. doi: 10.1002/hep.21628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hidvegi T, Schmidt BZ, Hale P, et al. Accumulation of mutant alpha1-antitrypsin Z in the endoplasmic reticulum activates caspases-4 and -12, NFκB, and BAP31 but not the unfolded protein response. J Biol Chem. 2005;280:39002–39015. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M508652200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Papp E, Szaraz P, Korcsmaros T. Changes of endoplasmic reticulum chaperone complexes, redox state, and impaired protein disulfide reductase activity in misfolding α1-antitrypsin transgenic mice. FASEB J. 2006;20:1018–1020. doi: 10.1096/fj.05-5065fje. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mulgrew AT, Taggart CC, McElvaney NG. Alpha-1-antitrypsin deficiency: current concepts. Lung. 2007;185:191–201. doi: 10.1007/s00408-007-9009-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mulgrew AT, Taggart CC, Lawless MW, et al. Z α1-antitrypsin polymerizes in the lung and acts as a neutrophil chemoattractant. Chest. 2004;125:1952–1957. doi: 10.1378/chest.125.5.1952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]