Abstract

Here we describe a simple method to estimate the inner-sphere hydration state of the Mn(II) ion in coordination complexes and metalloproteins. The linewidth of bulk H217O is measured in the presence and absence of Mn(II) as a function of temperature, and transverse 17O relaxivities are calculated. It is demonstrated that the maximum 17O relaxivity is directly proportional to the number of inner-sphere water ligands (q). Using a combination of literature data and experimental data for twelve Mn(II) complexes, we show that this method provides accurate estimates of q with an uncertainty of ±0.2 water molecules. The method can be implemented on commercial NMR spectrometers working at fields of 7T and higher. The hydration number can be obtained for micromolar Mn(II) concentrations. We show that the technique can be extended to metalloproteins or complex:protein interactions. For example, Mn(II) binds to the multi-metal binding site A on human serum albumin with two inner-sphere water ligands that undergo rapid exchange (1.06 × 108 s−1 at 37 °C). The possibility of extending this technique to other metal ions such as Gd(III) is discussed.

Keywords: Manganese, Paramagnetic NMR, hydration state, contrast agent, serum albumin

Introduction

The hydration state of metal ions in aqueous solution is fundamental to a variety of physical, chemical and biological processes. It has been proposed that selectivity in ion transport across cellular membranes is driven by a topological control mechanism, where the thermodynamics of transport correlate directly to hydration number rather than affinity for ligand donors found within the transport channel.1,2 Studies also suggest that the immediate solvation environment exerts direct control over the energetics and composition of the frontier molecular orbitals in reactive transition metal complexes.3 Additionally, the solvation properties of a given ion can be reflective of macroscopic properties, and information regarding bulk environment can be extrapolated through probing this microscopic feature.4–6 Although the hydration state of metal ions underlies essential physical and life processes, this fundamental property can be difficult to discern.

X-ray crystallography can provide high-resolution structural data of small complexes and macromolecules, but static structures obtained from crystalline samples do not always accurately describe solvent binding, equilibrium compositions and environmentally triggered structural changes evidenced by solution spectroscopic techniques.7–12 Additionally, this technique is limited by the need to obtain well-formed single crystals, which is not tenable for all samples. Extended X-ray absorbance fine structure (EXAFS) spectroscopy probes the primary coordination sphere of metal ions in solution,13–20 but cannot necessarily distinguish or quantify the number of water ligands and requires access to a specialized facility with tunable synchrotron radiation. Solution neutron diffraction can determine the hydration state of ions in solution, but this technique also requires highly specialized instrumentation and very high (molar) concentrations.21,22 At molar concentrations, intermolecular interactions become increasingly significant resulting in changes in hydration state that do not reflect those relevant to physiological or catalytic processes.23,24 To date, reports of solution structures determined through neutron diffraction are limited to species formed upon dissolution of simple salts.

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) is also used to probe the hydration state of metal complexes in solution. If water exchange is slow enough, the metal-bound H217O resonance can be directly integrated to determine the number of water ligands (q). Most often, water exchange is too rapid and cannot be resolved from the bulk water signal.25 For certain paramagnetic ions such as Dy(III) or Tb(III) that induce a large chemical shift without significant line broadening, the concentration dependent change in the H217O resonance may be proportional to the hydration number.26,27 Time resolved luminescence can also be used to determine q, although this is limited to the lanthanides.

Unfortunately none of these techniques are very useful for probing the hydration state of Mn(II). Moreover, one cannot predict the hydration state by chemical intuition. The lack of ligand field stabilization energy results in no preference for specific coordination numbers or geometries. For instance coordination numbers of five through eight have been observed crystallographically for high spin Mn(II).7,12,28–33 The coordination number of Mn(II) complexes varies even when held within ligand frameworks of identical denticity. Determining the coordination number and hydration state of Mn(II) in solution is challenging. Yet understanding the hydration state of Mn(II) is critical in understanding the structure and function of Mn(II) species in chemistry and biology.

Mn(II) is biogenic and trace Mn is a nutrient essential to the function of several enzymes and physiological processes.34 For example, Mn plays a key role in anti-oxidant defense and serves as the transition metal co-factor utilized in catalase,35,36 which disproportionates adventitious hydrogen peroxide, and as a metal cofactor in the superoxide dismutase isoform found in the eukaryotic mitochondria.37–40 Mn(II) has also been shown to play a key structural role in certain DNA and RNA polymerases and kinases, amongst other enzymes performing essential life processes.41–44 Mn homeostasis is a delicate balance, and Mn overload is associated with neurological decline characterized by symptoms similar to those associated with idiopathic Parkinson’s disease, commonly referred to as manganism.45 It is understood that Mn(II) accumulates in neurons through voltage dependent Ca(II) channels and is subsequently shuttled around the nervous system. However, little information is known as to the speciation of Mn(II) in neurons and the mechanisms of Mn(II) trafficking and homeostasis are largely unresolved and have been a subject of intense scrutiny.

High-spin Mn(II) (S=5/2) is a potent T1-relaxation agent that can be used to generate contrast in magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), and understanding hydration is key to understanding function.46,47 For example the neurological activity of Mn(II) has been exploited for mapping neuronal structures and pathways, and this is done by administration of MnCl2 to afford contrast in pre-clinical neuroimaging applications.48–51 Mn(II) uptake has also been utilized as a measure of cell viability through correlating signal enhancement to cellular function. For example, this strategy has been used to track changes in β-cell mass in studies pertaining to the onset and progression of type diabetes.52 Mn(II) uptake in hepatocytes has also been used to visualize hepatic lesions.53,54 However the molecular forms of Mn(II) in the brain, pancreas, or liver are unknown, e.g. does the Mn2+ aqua ion persist or does it bind to an endogenous low molecular weight or macromolecular ligand? Probing Mn(II) hydration in these systems would begin to address such questions.

There is also a growing interest in developing stable Mn(II) coordination complexes for use as MRI relaxation agents.12,31,32,55–62 The identification of nephrogenic systemic fibrosis, a rare but serious disorder associated with dissociated Gd(III),63–65 coupled with a growing interest in MR probes capable of providing metabolic information to accompany structural images are driving factors behind this growing body of research.66–68 For example, our group is interested in exploiting the Mn(III/II) redox couple to design MR probes that are responsive to altered redox homeostasis associated with hypoxia or oxidative stress.69

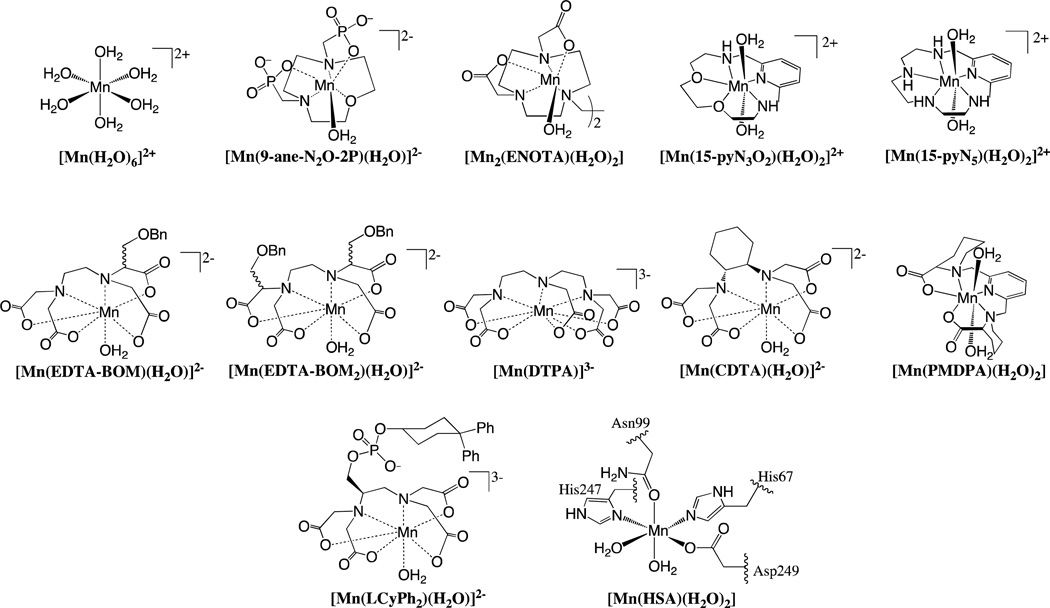

Here we show that the peak transverse 17O relaxivity, , of a Mn(II) complex reports directly on the hydration number. This result is predicated on the observation that the Mn(II) induced increase in H217O linewidth is almost entirely due to water exchange at field strengths commonly utilized for NMR spectroscopy. We show that q can be determined for a range of Mn(II) complexes (Chart 1) and for Mn(II) associated with proteins.

Chart 1.

Mn(II) complexes explored in this study.

Results and Discussion

Relationship between hydration number and H217O NMR chemical shift

High spin Mn(II) complexes have no ligand field stabilization and are extremely labile. This results in very fast exchange of coordinated water ligand(s). The spin delocalization from the Mn(II) ion to the oxygen donor atom or proton on the water ligand is described by the hyperfine coupling constants Ao/ℏ and AH/ℏ, respectively. For Mn(II), one does not expect Ao/ℏ to vary considerably regardless of the other ligand(s) in the complex. Literature values of Ao/ℏ for Mn-17OH2 range from 2.6 to 4.1 × 10 rad/s, with the aqua ion having a hyperfine coupling constant in the middle of this range (3.3 × 107 rad/s).57,73,74 There are fewer reports regarding AH/ℏ, but hyperfine coupling constants between 3.8 and 6.3 × 106 rad/s have been reported for [Mn(H2O)6]2+.75

In principle, the paramagnetic shift of the 17O or 1H NMR signal induced by Mn(II) should yield the hydration number q. In the fast exchange regime (where the exchange rate kex is much larger than the transverse relaxation rate (1/T2m) of the coordinated water, see Appendix in SI) the paramagnetic chemical shift Δωp is given by eq 1, where ωref is the frequency of 17O or 1H in the absence of Mn(II), B0 is the applied magnetic field, and the other symbols have their usual meanings.75–77 Given the relative invariance in Ao/ℏ (and presumably AH/ℏ), Mn(II) should affect the chemical shift in a predictable manner. The hydration number should be readily attained from the slope of a plot of Δωp vs [Mn] at a fixed temperature. Alternately, one can estimate q from the dependence of Δωp on temperature.

| (1) |

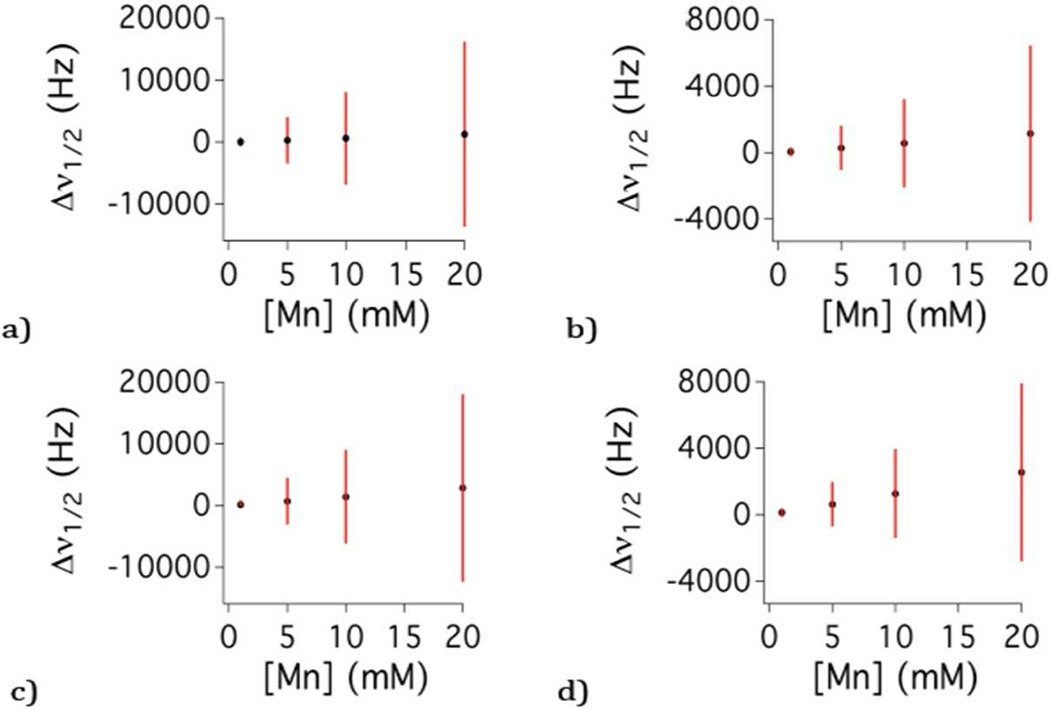

In practice this is very difficult because Mn(II) is such a potent relaxation agent and the inherent linewidths are large, rendering accurate assignment of chemical shift difficult. This problem is explored in Figure 1 for [Mn(H2O)6]2+, which displays calculated H217O chemical shift and full width at half height linewidth data (see below). Figure 1a shows the concentration dependent chemical shift at 55 °C and 9.4T in Hz with linewidth at half height (Δν1/2) denoted as bars. For example, 10 mM Mn2+ changes the H217O chemical shift by 640 Hz, but Δν1/2 is 14,900 Hz. Increasing the temperature to 90 °C (Figure 1b) reduces the linewidth to 5,300 Hz, but this is still much larger than the chemical shift (570 Hz), and the broad lines obscure precise assignment of chemical shift. Figure 1c–d show the effect of moving to a higher field to increase the shift. Even at 21T, the shifts are small relative to the linewidth. Calculated 1H2O chemical shift and half height linewidth (Figure S1) depict similar difficulties.

Figure 1.

Concentration dependence on H217O chemical shift (black dots) and linewidth at half-height (red bars) simulated from the previously reported hyperfine coupling constant, water exchange and electronic relaxation parameters for [Mn(H2O)6]2+ at various field strength and temperature: (a) 55 °C, 9.4T; (b) 90 °C, 9.4T; (c) 55 °C, 21T; (d) 90 °C, 21T.

Relationship between hydration number and linewidth

An alternate approach is to take advantage of the enhanced transverse relaxation rates. For Mn(II), the induced chemical shift is very small relative to the increase in signal linewidth. The observed paramagnetic relaxation rate (1/T2p), and thus linewidth, is defined by the residency time of the water ligand (τm, the inverse of the water exchange rate, kex), T2m, the Mn(II) concentration, and q (eq 2). When T2m >> τm (fast exchange regime), the observed paramagnetic relaxation rate will increase with decreasing temperature and reach a maximum where T2m = τm, and will then decrease as τm becomes larger than T2m.

| (2) |

Relaxation of the coordinated H217O is dominated by the scalar mechanism (eqs 3–4) which depends on the hyperfine coupling constant and a correlation time (τsc) that is dictated by either the water residency time or the T1e of the unpaired electrons. Relaxation of the coordinated 1H2O occurs via multiple mechanisms and discussed in the SI.

| (3) |

| (4) |

For Mn(II), the electronic relaxation time increases with the square of the applied magnetic field.78–80 Thus at sufficiently high field, the correlation time for scalar relaxation (and T2m) will be the water residency time τm. The implication of this condition is that at the maximum paramagnetic 17O relaxation rate, where T2m = τm, one can rearrange equations 2 and 3 and solve for q, eq 5.

| (5) |

Here we introduce the term which is the transverse 17O relaxivity, defined analogously to proton relaxivity (Δ(1/T2)/[Mn]). In this case, we can calculate the maximum 17O transverse relaxivity for a given q and hyperfine coupling constant. For the range of Mn-17OH2 hyperfine coupling constants, this leads to mM−1s−1. per q. This is a powerful result because it means that q can be estimated from a few variable temperature H217O linewidth measurements. Using this method we expect q can be solved within ±0.2 accuracy simply by fixing Ao/h to 3.3×107 rad/s. It should be noted that routinely employed chemical shift analysis of Ln(III) complexes (excluding Gd(III)), which all exhibit short T1e and thus narrow Δν1/2, also yields q within ±0.2.81

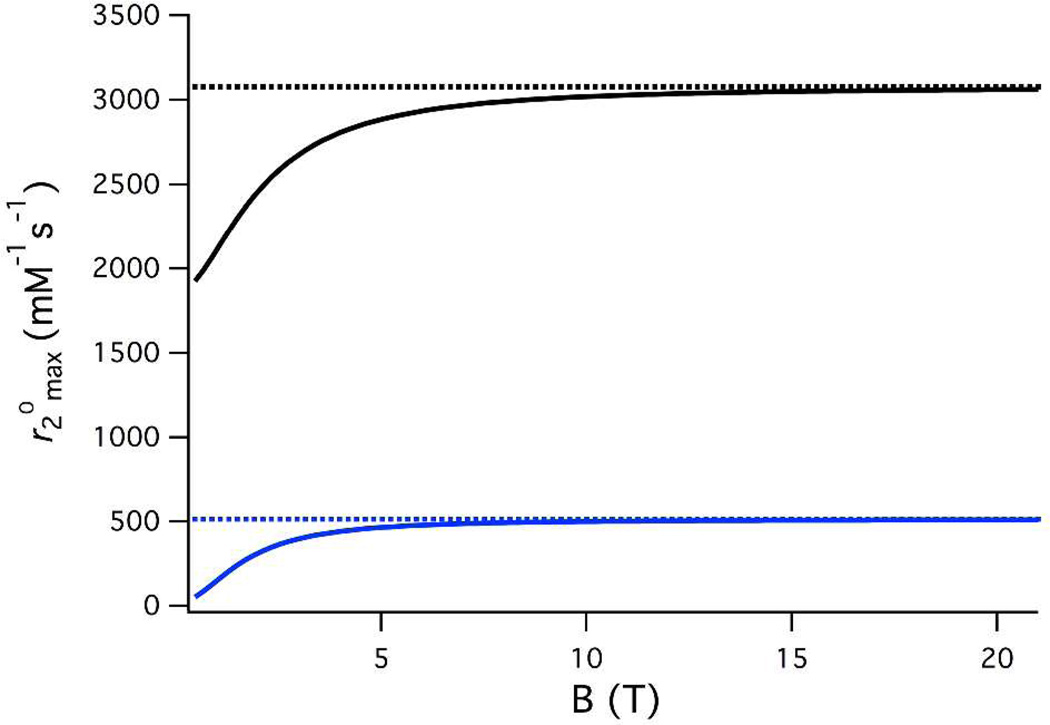

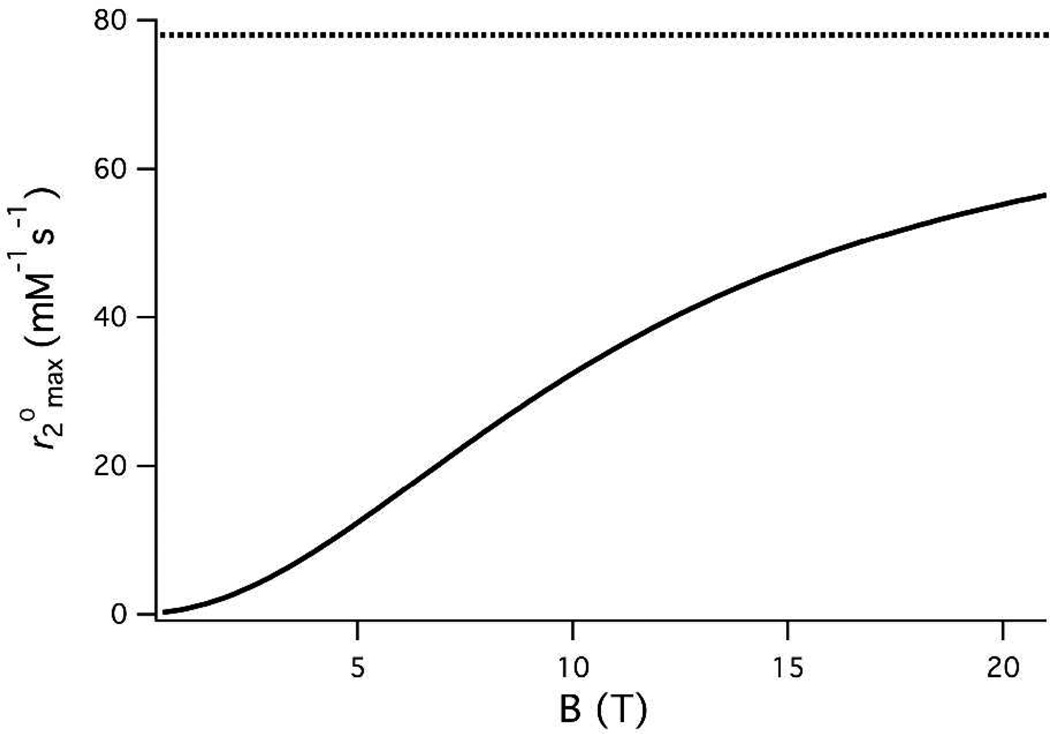

To test the assumption that the water residency time dominates the scalar relaxation mechanism at high field (τm << T1e), we first examined the literature on Mn(II) complexes where electronic relaxation parameters were given (see Supporting Information and Table S1).12,31,32,59,71,72,82 In this regard, we simulated the effects of varying temperature and applied field on between 0 and 100 °C and 0.47 and 21 T. Figure 2 depicts the calculated dependence of on applied field for [Mn(H2O)6]2+ and [Mn(9-ane-N2O-2P)(H2O)]2− (simulations for six other Mn(II) complexes are shown in Figure S1–S8) based on the reported hyperfine coupling constants, water exchange and electronic relaxation parameters.12,57,59,70,72 In Table 1, we list calculated values at 7, 11.7, 21T and ∞T (where T1e has no effect of scalar relaxation) for eight Mn(II) complexes from the literature. At 7T, the effect of T1e on is less than 9% and this drops to 3% or less at 11.7T. Thus it would appear that the simple measurement of is a reasonable means to estimate q at field strengths used on modern NMR spectrometers.

Figure 2.

Simulated field dependence of for [Mn(H2O)6]2+ (black) and [Mn[9-ane-N2O-2P)(H2O)]2− (blue). Dotted lines represent at ∞T.

Table 1.

Simulated (mM−s−1 ) generated from the hyperfine coupling constants, water exchange and electronic relaxation parameters of previously reported Mn(II) complexes.12,32,59,70–72

| 7T | 11.7T | 21T | ∞T | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Mn(H2O)6]2+ | 2970 | 3037 | 3063 | 3076 |

| [Mn(9-ane-N2O-2P)(H2O)]2− | 487 | 503 | 510 | 513 |

| [Mn2(ENOTA)(H2O)2)] | 499 | 502 | 503 | 503 |

| [Mn(15-pyN3O2)(H2O)2] | 1121 | 1158 | 1178 | 1188 |

| [Mn(15-pyN5)(H2O)2] | 1171 | 1182 | 1186 | 1188 |

| [Mn(EDTA-BOM)(H2O)]2− | 564 | 576 | 581 | 584 |

| [Mn(EDTA-BOM2)(H2O)]2 | 575 | 580 | 582 | 584 |

| [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2− | 371 | 393 | 402 | 406 |

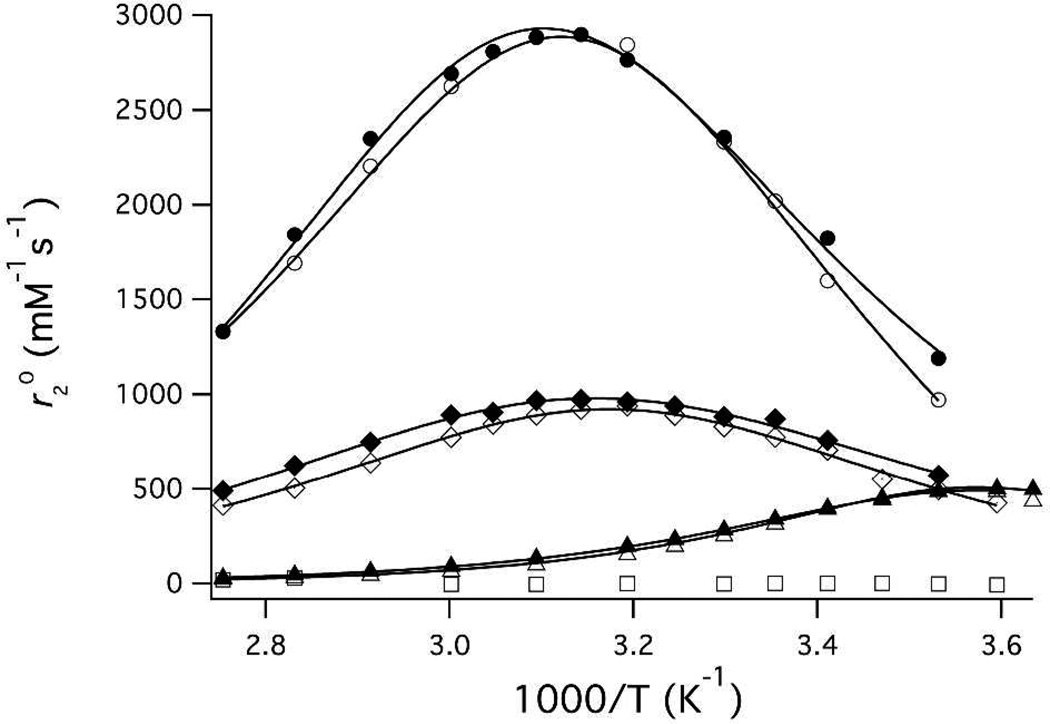

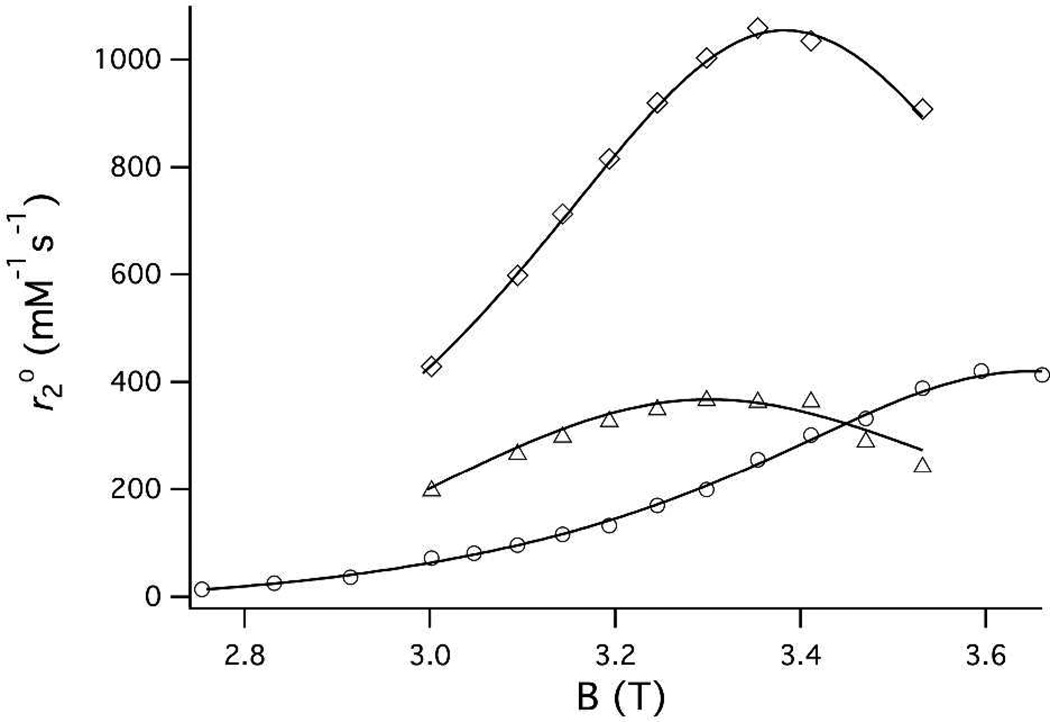

To confirm these results, we measured the variable temperature for five compounds with differing hydration state and water exchange kinetics. Figure 3 shows as a [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2−, [Mn(PMPDA)(H2O)2] and [Mn(DTPA)3−. The relaxivities were measured at 9.4 and 11.7T to assess the influence of field on and are listed in Table 2. The hydration numbers estimated by this method are the same at 9.4 and 11.7T and agree with the expected values based on crystal structures and analogous compounds.70,72,83

Figure 3.

Plots of as a function of temperature for [Mn(H2O)6]2+ (circles), [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2− (triangles), [Mn(PMPDA)(H2O)2] (diamonds) and [Mn(DTPA)]3− (squares) at 9.4 T (solid symbols) and 11.7 T (open symbols). Solid lines represent fits to the data (see text).

Table 2.

Measured and calculated hydration numbers (q) using eq 5 for [Mn(H2O)6]2+;, [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2− and [Mn(PMDPA)(H2O)2] at 9.4 and 11.7T.

|

(mM−1 s−1) |

q | |

|---|---|---|

| [Mn(H2O)6]2+ (9.4T) | 2970 | 5.79 |

| [Mn(H2O)6]2+ (11.7T) | 2840 | 5.54 |

| [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2− (9.4T) | 460 | 0.90 |

| [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2− (11.7T) | 460 | 0.90 |

| [Mn(PMDPA)(H2O)2] (9.4T) | 970 | 1.89 |

| [Mn(PMDPA)(H2O)2] (11.7) | 940 | 1.83 |

| [Mn(DTPA)]3− (11.7T) | 0 | 0 |

Water exchange kinetics

The data in Figure 3 can be analyzed to estimate water exchange kinetics for these three complexes. The rate constants and activation energies are listed in Tables 3–5 along with comparisons to previous studies. We analyzed the variable temperature data in three ways, and χ2 values are given to indicate the quality of the fits. In the model 1, we fit the data to a four-parameter model by varying τm310, T1e310, ΔH≠ and ΔET1e (see Supporting Information) and assumed an exponential temperature dependence on water exchange and electronic relaxation.84 Here we set q equal to the 1, 2 and 6 for [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2−, [Mn(PMPDA)(H2O)2] and [Mn(H2O)6]2+, respectively, and assumed a common hyperfine coupling constant of 3.3×107 rad/s. In this case, the data fit well but there were very large relative uncertainties associated with the electronic relaxation parameters, indicating that electronic relaxation does not contribute to the measured 17O T2 values. In model 2 we ignored the effect of electronic relaxation and fit the data to only two parameters: the water residency time at 310K and the activation enthalpy for water exchange. As expected, the quality of the 2-parameter fit is similar to the 4-parameter fit in model 1. In model 3, we again ignored electronic relaxation, but this time allowed the hyperfine coupling constant to vary. Model 3 gives equivalent water exchange kinetic parameters but somewhat better fits. This is expected since the method gave slightly non-integer q values. By fixing q to integer values, the hyperfine constant will adjust to reflect this difference. The water exchange rate and enthalpy of activation are in good accord for all three models for the three complexes. The water exchange kinetic parameters were also consistent at both fields where measurements were made. These findings underscore the observation that electronic relaxation is sufficiently long and negligibly affects T2m at these field strengths.

Table 3.

Water exchange and electronic relaxation parameters yielded by three different fits of temperature dependent transverse H217O relaxation in the presence of [Mn(H2O)6]2+.

| q |

Ao/ℏ (x107 rad/s) |

τm310 (ns) |

T1e (ns) |

ΔH≠ (kJ/mol) |

ΔET1e (kJ/mol) |

χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lit. | 6 | 3.33 | 27.3 | -- | 32.9 | -- | |

| Method 1 (9.4T) | 6 | 3.33 | 29.4±0.9 | 471±143 | 26.1±1.1 | −60.7.±7.5 | 0.0047 |

| Method 1 (11.7T) | 6 | 3.33 | 28.8±10.8 | 321±2410 | 32.0±6.8 | −17.4±504 | 0.0085 |

| Method 2 (9.4T) | 6 | 3.33 | 26.5±0.6 | -- | 30.0±0.6 | -- | 0.0189 |

| Method 2 (11.7T) | 6 | 3.33 | 28.4±0.5 | -- | 32.7±0.5 | -- | 0.0124 |

| Method 3 (9.4T) | 6 | 3.18±0.04 | 28.5±0.5 | -- | 28.5±0.6 | -- | 0.0073 |

| Method 3 (11.7T) | 6 | 3.23±0.06 | 28.9±0.6 | -- | 31.7±0.8 | -- | 0.0091 |

| Average/ Std. | -- | -- | 28.4±1.3 | -- | 30.0±2.4 | -- |

Table 5.

Water exchange and electronic relaxation parameters yielded by three different fits of temperature dependent transverse H217O relaxation in the presence of [Mn(PMDPDA)(H2O)2].

| q |

Ao/ℏ (x107 rad/s) |

τm310 (ns) |

T1e (ns) |

ΔH≠ (kJ/mol) |

ΔET1e (kJ/mol) |

χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lit. | 2 | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- | -- |

| Method 1 (9.4T) | 2 | 3.33 | 23.2±0.7 | 292±64 | 21.5±1.2 | −45.9±7.8 | 0.0044 |

| Method 1 (11.7T) | 2 | 3.33 | 23.5±1.5 | 100±18 | 25.7±1.6 | −31.2±12.6 | 0.0083 |

| Method 2 (9.4T) | 2 | 3.33 | 21.4±0.5 | -- | 24.8±0.5 | -- | 0.0170 |

| Method 2 (11.7T) | 2 | 3.33 | 21.0±0.3 | -- | 26.6±0.3 | -- | 0.0811 |

| Method 3 (9.4T) | 2 | 3.19±0.03 | 22.0±0.3 | -- | 23.2±0.5 | -- | 0.0051 |

| Method 3 (11.7T) | 2 | 2.99±0.03 | 23.2±0.3 | -- | 26.0±0.4 | -- | 0.0083 |

| Average/ Std. | -- | -- | 23.2±3.5 | -- | 26.5±3.6 | -- | -- |

Sensitivity and scope of q determination

Because Mn(II) is such a potent relaxation agent, this method of q estimation can be used at sub-millimolar concentrations. The main limitation is the fast diamagnetic relaxation of H217O which increases with decreasing temperature. If we conservatively assume that at peak relaxivity, the paramagnetic relaxation rate should contribute 10% of the observed relaxation rate, then one would only require between 10 and 50 µM Mn(II) for a q = 1 complex, depending on the temperature of (higher sensitivity at higher temperatures). Because crossover into the fast exchange regime must occur between 0 and 100 °C to identify this method cannot be successfully applied to complexes that display extremely fast exchange kinetics (τm310 < 2 ns), in which case T2m = τm occurs below the freezing point of water, or complexes that display very slow exchange kinetics (τm310 > 200 ns). However water exchange rates of all Mn(II) complexes reported to date, including the compounds in this study, fall within this range, suggesting that this methodology should be ideally suited for the study of most Mn(II) complexes.

Extension to complex:protein interactions

The relatively high sensitivity of this technique allows for the interrogation of hydration number for Mn(II) complexes interacting with proteins. As an example, we investigated [Mn[EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− as a function of temperature in 4.5% w/v human serum albumin (HSA) at pH 7.4 (50 mM HEPES buffer). In this case 1/T2ref was determined from the temperature dependence of a HSA solution that contained no Mn(II). [Mn[EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− was designed to non-covalently bind to drug binding site 2 of HSA, a hydrophobic pocket associated with the binding and transport of lipophilic substrates. This complex has been shown to be 98% protein-bound at 310 K at the concentration employed in this experiment (0.1 mM).85 1H relaxometry methods performed on [Mn[EDTACyPh2)(H2O)3− in HSA suggest contributions from a Mn(II)-coordinated water to T1-relaxation, but the hydration state of the Mn(II) ion in this adduct has not been formally probed.

The temperature dependent of [Mn(EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− recorded in neat H2O and HSA solution is shown in Figure 4; the hydration state estimated from and relevant exchange parameters are tabulated in Table 6. The calculated hydration state of 0.72 of HSA-bound [Mn(EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− suggests the possibility of some q = 0 species present. It is known that protein side chains can displace water ligands in Gd(III) complexes when bound to HSA,5,86 although this is typically seen with q = 2 complexes. The water exchange rate of [Mn(EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− is four-fold slower when the complex is bound to HSA and highlights the fact that HSA-binding strongly influences the interaction of this complex with bulk water. This study highlights the sensitivity of Mn(II) induced relaxation to probe hydration and water exchange kinetics for protein-bound complexes.

Figure 4.

Transverse 17O relaxivity, , as a function of temperature at 11.7T for [Mn[EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− in water (circles) and in 4.5% w/v HSA at pH 7.4 (triangles), and the Mn(II)-HSA complex at pH 8.6 (diamonds). Solid lines represent fits to the data (see text).

Table 6.

Water exchange parameters obtained using model 1 (Ao/ℏ = 3.3×107 rad/s) from the temperature dependent transverse relaxation in the presence of [Mn(EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− in water, and in 4.5% w/v HSA, and for Mn(II) ligated by multi-metal binding site A of HSA; q (fit) denotes the q value used in the fitting procedure.

|

(mM−1 s−1) |

q (calcd) |

q (fit) |

τm310 (ns) |

T1e (ns) |

ΔH≠ (kJ/mol) |

ΔET1e (kJ/mol) |

χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| [Mn(EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− | 430 | 0.84 | 1 | 3.3±0.5 | 21±18 | 21.1±3.8 | −73.4±13.1 | 0.0594 |

| [Mn(EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3−•HSA | 340 | 0.66 | 0.7 | 13.7±2.3 | 803±2600 | 26.4±5.7 | −11.6±61.0 | 0.0461 |

| Mn(II)•HSA | 1060 | 2.06 | 2 | 9.4±0.3 | 1239±4290 | 30.6±1.1 | −77.4±44.3 | 0.0012 |

Extension to metalloproteins

As a second example, we sought to determine the hydration number of the Mn(II) ion when it was coordinated by human serum albumin (HSA). In the presence of HSA, Mn(II) binds preferentially to a motif denoted multi-metal binding site A, found at the interface of two subdomains (I and II) and comprised of His67, Asn99 His247 and Asp249.87 This mixed N/O binding site is conserved throughout all mammalian serum albumins. The affinity for multi-metal site A for Mn(II) has been studied as a function of pH, Mn(II) concentration and concentration of competitor ions and substrates through proton relaxation enhancement techniques.87–89 As a result, the interaction of Mn(II) and HSA is relatively well defined. However, the solution structure of the Mn(II) ion in multi-metal site A has never been explored.

The of Mn(II)-HSA as a function of temperature was recorded at 0.1 mM and pH 8.6 (50 mM Tris buffer) (Figure 4). Under these conditions we can expect Mn(II) to exclusively reside in site A.87 A hydration state of q = 2 was calculated from the value; the water exchange parameters are listed in Table 6. Previous study of Zn(II) housed within site A by EXAFS suggests five-coordinate Zn(II), bound by the aforementioned residues and one water.90 The backbone carbonyl of His247 was also found to interact with the Zn(II) ion but the Zn-O distance is too large for this donor to be considered a part of the primary coordination sphere. The bis(aquated) nature of the Mn(II) adduct is likely a result of the expanded radius of the Mn(II) ion relative to Zn(II). We note that we could successfully reproduce this result using a solution containing 25 µM Mn(II), which further highlights the sensitivity of this method for biomolecule applications.

Comparison of Mn(II) water exchange kinetics

The τm310 values recorded for [Mn(H2O)6]2+, [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2− and [Mn(EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− agree with those obtained previously. This study is the first report on the exchange kinetics measured by 17O transverse relaxation rates for the q=2 complex [Mn(PMDPA)(H2O)2]. The exchange kinetics of [Mn(PMDPA)(H2O)2] fall within the range defined by the handful of Mn(II) complexes housed within rigid, pentadentate ligands.32,82,91 We found that [Mn(EDTACyPh2)(H2O)]3− underwent four-fold slower water exchange upon protein binding. A decrease in water exchange rate has also been observed for Gd(III) complexes binding to HSA.92–94 Hydrogen bonding to the coordinated water molecule by protein sidechains in the binding pocket may slow water exchange. Mn2+ bound to HSA has been previously studied at pH 7.0 by 1H N MRD and 17O NMR at 2.1T and a τm310 of 12–15 ns was reported. However, histidine (pKa ~6.7) coordination to Mn(II) at multi-metal binding site A is pH dependent and it is likely that the Mn(II) species explored in that study is different than that recorded here.

Extension of technique to Gd(III) complexes

Given the similarity in relaxation mechanisms between Mn(II) and Gd(III), and because of the importance of hydration state in the application of Gd(III) complexes as MRI contrast agents, we investigated whether the approach could be taken with Gd(III). The hyperfine coupling constant Ao/ℏ for Gd-17OH2 is well established from NMR and EPR studies to be 3.8 × 106 rad/s,95 and this leads to mM−1s−1 per q in the absence of contributions from T1e.

We retrospectively analyzed some data obtained at 7T for eight different Gd(III) complexes based on DOTA or DTPA ligands (Figure S10, Table S2) and of known hydration state.

These compounds showed a range of values from 22 to 33 mM−1s−1 per q. These values are far from the value predicted if there is no contribution to scalar relaxation from T1e. Indeed the T1e values for these complexes are comparable to τm and the assumptions leading to eq 5 break down.

We also made some relaxation rate measurements at 11.7T on [Gd(DTPA)(H2O)]2−, [Gd(HPDO3A)(H2O)], [Gd(DTPA-BMA)(H2O)], [Gd(DOTAla)(H2O)], and [Gd(CyPic3A)(H2O)2]− (Figure S11, Table S3). The values at this field strength ranged between 25.2 and 40.9 mM−1s−1. It is apparent that the values measured at 11.7T are still far from approaching the ∞T limit (where T1e is negligible). Thus, variations in T1e induced by either changes in magnetic field or differences in the ligand field make q determination by this technique unpredictable. For example, for [Gd(CyPic3A)(H2O)2]− is 62% greater than the value measured for [Gd(HPDO3A)(H2O)].

Figure 5 shows the dependence of on external field for [Gd(HPDO3A)(H2O)] simulated from recently reported zero-field splitting parameters.96 This plot is generally reflective of all Gd(III) complexes considered in this study. Although direct measurement of may not represent a reliable method to estimate q for Gd(III), there exist numerous reliable strategies to obtain this value.26,27,81,97

Figure 5.

Simulated field dependence of for [Gd(HPDO3A)(H2O)] at 49 °C; occurs at this temperature at 5T and above. Dotted line represents at ∞T.

The failure of this method applied to Gd(III) is best understood in terms of the nature of the interaction between the coordinated water and unpaired electrons. As a result of lanthanide contraction, the 4f electrons of Gd(III) are well shielded and interact weakly with the coordinated H217O, whereas the 3d electrons of Mn(II) are much more accessible. The mechanism of spin delocalization from Gd(III) to H217O is inefficient relative to Mn(II), which results in nearly an order of magnitude difference in hyperfine coupling constant. In turn, the relaxation time for a coordinated water ligand (T2m) to Mn(II) is nearly an order of magnitude shorter than for a water coordinated to Gd(III) with equivalent water exchange kinetics and electronic relaxation. Because is achieved when T2m = τm, the mean water residency time at this event will be significantly shorter for a Mn(II) complex than for a Gd(III) complex with similar electronic relaxation. For instance although the of [Mn(H2O)6]2+ and [Gd(HPDO3A)(H2O)] occur at similar temperatures (45–50 °C), their water residency times at this maximum are 18 and 113 ns, respectively. Because τm at is much shorter for Mn(II), the influence of T1e on T2m is negligible at high fields and the approximations leading to eq 5 are valid.

Conclusion

The hydration state of Mn(II) can be inferred directly from H217O lin ewidths. This is because longitudinal electronic relaxation effects Mn(II) induced T2-relaxation only negligibly at magnetic fields found on modern NMR spectrometers. This phenomena was validated through simulations of as a function of temperature and field strength corresponding to eight Mn(II) complexes from the literature for which electronic relaxation parameters are reported and through measurement of seven unique Mn(II) complexes at 9.4 and/or 11.7T. Due to the tremendous line-broadening effect of Mn(II), this information can be obtained using micromolar Mn(II) concentrations. In this regard, this technique was successfully extended to measure the hydration state and water exchange parameters of a Mn(II) complex non-covalently bound to HSA and to Mn(II) directly coordinated by HSA. We anticipate that this simple NMR technique will find great utility in future studies directed towards understanding the solution structure of Mn(II) containing species.

Experimental

General

All materials were purchased commercially, excepting PMDPA, which was prepared as reported.83 NMR spectra were recorded on either a 9.4 or 11.7 T Varian spectrometer equipped with a 5 mm broadband probe. The transverse relaxation times of O-17 were measured through the linewidth of the H217O NMR signal at half-height.92 The values obtained through this method were in excellent agreement with those obtained using the CPMG pulse sequence. Relaxivity was calculated by dividing the Mn(II) or Gd(III) imparted increase in 1/T2 relative to neat H2O at pH 3 by the concentration of the paramagnetic ion in mM. For samples in HSA solution, the increase in relaxation rate was measured relative to the HSA solution alone at the same temperature. Samples were enriched to contain between 0.1 and 0.2% H217O. Samples were prepared by adding slightly substoicheometric quantities of Mn(II) or Gd(III) to the ligand solution to ensure full ion chelation, and the pH adjusted to ~6.5 for complexes of Gd(III) or to pH 7–8 for complexes of Mn(II). [Mn(PMDPA)(H2O)2] was prepared by adding Mn(II) to ligand in 50 mM HEPES buffer at pH 7.4. The pH was measured using a ThermoOrion pH meter connected to a VWR Symphony glass electrode. Mn and Gd concentrations were determined using an Agilent 7500a ICP-MS system. All samples were diluted with 0.1% Triton X-100 in 5% nitric acid containing 20 ppb of Lu (as internal standard). The ratio of Mn (54.94) or Gd (157.25)/Lu (174.97) was used to quantify the metal concentration. A linear calibration curve ranging from 0.1 ppb to 200 ppb was generated daily for the quantification.

Supplementary Material

Table 4.

Water exchange and electronic relaxation parameters yielded by three different fits of temperature dependent transverse H217O relaxation in the presence of [Mn(CDTA)(H2O)]2−.

| q |

Ao/ℏ (x107 rad/s) |

τm310 (ns) |

T1e (ns) |

ΔH≠ (kJ/mol) |

ΔET1e (kJ/mol) |

χ2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lit. | 1 | 2.64 | 3.5 | -- | 42.5 | -- | -- |

| Method 1 (9.4T) | 1 | 3.33 | 4.4±0.2 | 38±10 | 28.0±0.6 | −33.3±3.1 | 0.0018 |

| Method 1 (11.7T) | 1 | 3.33 | 3.7±4.8 | 29±375 | 35.9±23.2 | −37.3±224 | 0.0341 |

| Method 2 (9.4T) | 1 | 3.33 | 3.9±0 | -- | 31.8 ±0.4 | -- | 0.0088 |

| Method 2 (11.7T) | 1 | 3.33 | 3.3±0.1 | -- | 35.6 ±0.8 | -- | 0.0475 |

| Method 3 (9.4T) | 1 | 3.25±0.4 | 4.1±0.1 | -- | 31. 9±0.3 | -- | 0.0067 |

| Method 3 (11.7T) | 1 | 3.14±0.09 | 3.7±0.2 | -- | 35.8±0.7 | -- | 0.0344 |

| Average/Std. | -- | -- | 4.1±0.6 | -- | 33.2±3.2 | -- | -- |

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

We would like to thank Prof. Jack Szostak for access to a 9.4T NMR spectrometer.

Funding Sources

This work was supported by grants from the National Cancer Institute (CA161221 to PC and a T32 postdoctoral fellowship to EMG, CA009502), and an instrument grant (RR023385) from National Center for Research Resources. JZ (North Sichuan Medical College) is supported by the China Scholarship Council (File No. 201208510160).

Footnotes

ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Descriptions of the equations that define relaxation and two-site exchange, additional simulations and tables describing hyperfine coupling constant, water exchange and transient ZFS parameters of previously reported Mn(II) and Gd(III) complexes and a Table describing water exchange and electronic relaxation of Gd(III) complexes at 7 and 11.7T can be found in the supporting information. This information is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org/.

Author Contributions

The manuscript was written through contributions of all authors. All authors have given approval to the final version of the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bostick DL, Brooks CL., III Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci., U.S.A. 2007;104:9260. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0700554104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yu H, Noskov SY, Roux B. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2009;113:8725. doi: 10.1021/jp901233v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bernasconi L, Baerends EJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:8857. doi: 10.1021/ja311144d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lowe MP, Parker D, Reany O, Aime S, Botta M, Castellano G, Gianolio E, Pagliarin R. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:7601. doi: 10.1021/ja0103647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Moriggi L, Yaseen MA, Helm L, Caravan P. Chem. - Eur. J. 2012;18:3675. doi: 10.1002/chem.201103344. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Garcia-Martin ML, Martinez GV, Raghunand N, Sherry AD, Zhang S, Gillies RJ. Magn. Reson. Med. 2006;55:309. doi: 10.1002/mrm.20773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dube KS, Harrop TC. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:7496. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10579e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Diebold A, Hagen KS. Inorg. Chem. 1998;37:215. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gale EM, Cowart DM, Scott RA, Harrop TC. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:10460. doi: 10.1021/ic2016462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Leitch S, Bradley MJ, Rowe JL, Chivers PT, Maroney MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2007;129:5085. doi: 10.1021/ja068505y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Herbst RW, Perovic I, Martin-Diaconescu V, O'Brien K, Chivers PT, Pochapsky SS, Pochapsky TC, Maroney MJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2010;132:10338. doi: 10.1021/ja1005724. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Drahoš B, Pniok M, Havlíčková J, Kotek J, Císařová I, Hermann P, Lukeš I, Tóth E. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:10131. doi: 10.1039/c1dt10543d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gezahegne WA, Hennig C, Tsushima S, Planer-Friedrich B, Scheinost AC, Merkel BJ. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012;46:2228. doi: 10.1021/es203284s. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Moll H, Denecke MA, Jalilehvand F, Sandström M, Grenthe I. Inorg. Chem. 1999;38:1795. doi: 10.1021/ic981362z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Spångberg D, Hermansson K, Lindqvist-Reis P, Jalilehvand F, Sandström M, Persson I. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2000;104:10467. doi: 10.1021/ja001533a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Frank P, Benfatto M, Hedman B, Hodgson KO. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:2086. doi: 10.1021/ic2017819. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Migliorati V, Mancini G, Tatoli S, Zitolo A, Filipponi A, De Panfilis S, Di Cicco A, D’Angelo P. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:1141. doi: 10.1021/ic302530k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Atta-Fynn R, Bylaska EJ, de Jong WA. J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 2013;4:2166. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bowron DT, Beret EC, Martin-Zamora E, Soper AK, Marcos ES. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2012;134:962. doi: 10.1021/ja206422w. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Jalilehvand F, Spångberg D, Lindqvist-Reis P, Hermansson K, Persson I, Sandström M. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2001;123:431. doi: 10.1021/ja001533a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Varma S, Rempe SB. Biophys. Chem. 2006;124:192. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.07.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ansell S, Barnes AC, Mason PE, Neilson GW, Ramos S. Biophys. Chem. 2006;124:171. doi: 10.1016/j.bpc.2006.04.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hewish NA, Neilson GW, Enderby JE. Nature. 1982;297:138. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mile V, Gereben O, Kohara S, Pusztai L. J. Phys. Chem. B. 2012;116:9758. doi: 10.1021/jp301595m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Helm L, Merbach AE. Chem. Rev. 2005;105:1923. doi: 10.1021/cr030726o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Alpoin MC, Urbano AM, Geraldes CFGC, Peters JA. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1992:463. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Djanashvili K, Peters JA. Contrast Media. Mol. Imag. 2007;2:67. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Erre LS, Micera G, Garribba E, Bényei AC. New J. Chem. 2000;24:725. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xiang DF, Duan CY, Tan XS, Hang QW, Tang WX. J. Chem. Soc. Dalton Trans. 1998:1201. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Polyakova IN, Sergienko VS, Poznyak AL. Crystallog. Reports. 2002;47:280. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Drahoš B, Kotek J, Císařová I, Hermann P, Helm L, Lukeš I, Tóth E. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:12785. doi: 10.1021/ic201935r. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Drahoš B, Kotek J, Hermann P, Lukeš I, Tóth E. Inorg. Chem. 2010;49:3224. doi: 10.1021/ic9020756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wang S, Westmoreland TD. Inorg. Chem. 2009;48:719. doi: 10.1021/ic8003068. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Reddi AR, Jensen LT, Culotta VC. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:4722. doi: 10.1021/cr900031u. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Waldo GS, Yu S, Penner-Hahn JE. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1992;114:5869. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Ivancich A, Barynin VV, Zimmermann J-L. Biochemistry. 1995;34:6628. doi: 10.1021/bi00020a008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Borgstahl GEO, Parge HE, Hickey MJ, Beyer WF, Hallewell RA, Tainer JA. Cell. 1992;71:107. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(92)90270-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Guan Y, Hickey MJ, Borgstahl GEO, Hallewell RA, Lepock JR, O'Connor D, Hsieh YS, Nick HS, Silverman DN, Tainer JA. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4722. doi: 10.1021/bi972394l. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hsieh YS, Guan Y, Tu CK, Bratt PJ, Angerhofer A, Lepock JR, Hickey MJ, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. Biochemistry. 1998;37:4731. doi: 10.1021/bi972395d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hearn AS, Fan L, Lepock JR, Luba JP, Greenleaf WB, Cabelli DE, Tainer JA, Nick HS, Silverman DN. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:5861. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M311310200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lovitt B, VanderPorten EC, Sheng Z, Zhu H, Drummond J, Liu Y. Biochemistry. 2010;49:3092. doi: 10.1021/bi901726c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Unciuleac M-C, Shuman S. Biochemistry. 2013;52:2967. doi: 10.1021/bi400281w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Blanca G, Shevelev I, Ramadan K, Villani G, Spadari S, Hübscher U, Maga G. Biochemistry. 2003;42:7467. doi: 10.1021/bi034198m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Zakharova E, Wang J, Konigsberg Biochemistry. 2004;43:6587. doi: 10.1021/bi049615p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Benedetto A, Au C, Aschner M. Chem. Rev. 2009;109:4862. doi: 10.1021/cr800536y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lauffer RB. Chem. Rev. 1987;87:901. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Caravan P, Farrar CT, Frullano L, Uppal R. Contrast Media. Mol. Imag. 2009;4:89. doi: 10.1002/cmmi.267. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Daoust A, Barbier EL, Bohic S. NeuroImage. 2013;64:10. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2012.09.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lindsey JD, Grob SR, Scadeng M, Duong-Polk K, Weinreb RN. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2013;31:865. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jin S-U, Lee J-J, Hong KS, Han M, Park J-W, Lee HJ, Lee S, Lee K-y, Shim KM, Cho JH, Cheong C, Chang Y. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2013;31:1143. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2013.03.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Jelescu IO, Nargeot R, Le Bihan D, Ciobanu L. NeuroImage. 2013;76:264. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dhyani AH, Fan X, Leoni L, Haque M, Roman BB. Magn. Reson. Imag. 2013;31:508. doi: 10.1016/j.mri.2012.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Chung J-J, Kim M-J, Kim KW. J. Magn. Res. Imag. 2006;23:706. doi: 10.1002/jmri.20557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Elizondo G, Fretz CJ, Stark DD, Rocklage SM, Quay SC, Worah D, Tsang YM, Chen MC, Ferrucci JT. Radiology. 1991;178:73. doi: 10.1148/radiology.178.1.1898538. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Pan D, Schmeider AH, Wickline SA, Lanza GM. Tetrahedron. 2011;67:8431. doi: 10.1016/j.tet.2011.07.076. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Drahoš B, Kubíček V, Bonnet CS, Hermann P, Lukeš I, Tóth E. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:1945. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01328e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Drahoš B, Lukeš I, Tóth E. Eur. J. Inorg. Chem. 2012:1974. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Rocklage SM, Cacheris WP, Quay SC, Hahn FE, Raymond KN. Inorg. Chem. 1989;28:477. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Aime S, Anelli PL, Botta M, Brocchetta M, Canton S, Fedeli F, Gianolio E, Terreno E. J. Biol. Inorg. Chem. 2002;7:58. doi: 10.1007/s007750100265. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zhang Q, Gorden JD, Beyers RJ, Goldsmith CR. Inorg. Chem. 2011;50:9365. doi: 10.1021/ic2009495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Kálmán FK, Tircsó G. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:10065. doi: 10.1021/ic300832e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Tei L, Gugliotta G, Fekete M, Kálmán FK, Botta M. Dalton Trans. 2011;40:2025. doi: 10.1039/c0dt01114b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Di Gregorio E, Gianolio E, Stefania R, Barutello G, Digilio G, Aime S. Anal. Chem. 2013;85:5627. doi: 10.1021/ac400973q. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Martin DR. Am. J. Kidney. Dis. 2010;56:427. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2010.07.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Stratta P, Canavese C, Quaglia M, Fenoglio R. Rheumatology. 2010;49:821. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/kep403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.De Leon-Rodriguez LM, Lubag AJM, Malloy CR, Martinez GV, Gillies RJ, Sherry AD. Acc. Chem. Res. 2009;42:948. doi: 10.1021/ar800237f. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Aime S, Botta M, Gianolio E, Terreno E. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2000;39:747. doi: 10.1002/(sici)1521-3773(20000218)39:4<747::aid-anie747>3.0.co;2-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Yu M, Beyers RJ, Gorden JD, Cross JN, Goldsmith CR. Inorg. Chem. 2012;51:9153. doi: 10.1021/ic3012603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Loving GS, Mukherjee S, Caravan P. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2013;135:4623. doi: 10.1021/ja312610j. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Ducommun Y, Newman KE, Merbach AE. Inorg. Chem. 1980;19:3696. [Google Scholar]

- 71.Balogh E, He Z, Hsieh W, Liu S, Tóth E. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:238. doi: 10.1021/ic0616582. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Maigut J, Meier R, Zahl A, van Eldik R. Inorg. Chem. 2008;47:5702. doi: 10.1021/ic702421z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Zetter MS, Grant MW, Wood EJ, Dodgen HW, Hunt JP. Inorg. Chem. 1972;11:2701. [Google Scholar]

- 74.Rolla GA, Platas-Iglesias C, Botta M, Tei L, Helm L. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:3268. doi: 10.1021/ic302785m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Bertini I, Luchinat C. NMR of Paramagnetic Substances. In: Lever ABP, editor. Coordination Chemistry Reviews. Vol. 150. Elsevier: Amsterdam; 1996. pp. 43pp. 77–110. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Bertini I, Fernández CO, Karlsson BG, Leckner J, Luchinat C, Malmström BG, Nersissian AM, Pierattelli R, Shipp E, Valentine JS, Vila AJ. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2000;122:3701. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Bertini I, Turano P, Villa AJ. Chem. Rev. 1993;93:2833. [Google Scholar]

- 78.Bloembergen N, Morgan LO. J. Chem. Phys. 1961;34:842. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Sur SK, Bryant RG. J. Phys. Chem. 1995;99:6301. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Miller JC, Sharp RR. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2000;104:4889. [Google Scholar]

- 81.Manus LM, Strauch RC, Hung AH, Eckermann AL, Meade TJ. Anal. Chem. 2012;84:6278. doi: 10.1021/ac300527z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Lieb D, Friedel FC, Yawer M, Zahl A, Khusniyarov MM, Heinemann FW, Ivanovíc-Burmazovíc I. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:222. doi: 10.1021/ic301714d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Su H, Wu C, Zhu J, Miao T, Wang D, Xia C, Zhao X, Gong Q, Song B, Ai H. Dalton Trans. 2012;41:14480. doi: 10.1039/c2dt31696j. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Caravan P, Parigi G, Chasse JM, Cloutier NJ, Ellison JJ, Lauffer RB, Luchinat C, McDermid SA, Spiller M, McMurry TJ. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:6632. doi: 10.1021/ic700686k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Troughton JS, Greenfield MT, Greenwood JM, Dumas S, Wiethoff AJ, Wang J, Spiller M, McMurry TJ, Caravan P. Inorg. Chem. 2004;43:6313. doi: 10.1021/ic049559g. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Zech SG, Sun W-C, Jacques V, Caravan P, Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM. ChemPhysChem. 2005;6:2570. doi: 10.1002/cphc.200500250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Fanali G, Cao Y, Ascenzi P, Fasano M. J. Inorg. Biochem. 2012;117:198. doi: 10.1016/j.jinorgbio.2012.08.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Aime S, Canton C, Crich SG, Terreno E. Magn. Reson. Chem. 2002;40:41. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Mildvan AS, Cohn M. Biochemistry. 1963;2:910. doi: 10.1021/bi00905a003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Blindauer CA, Harvey I, Bunyan KE, Stewart AJ, Sleep D, Harrison DJ, Berezenko S, Sadler PJ. J. Biol. Chem. 2009;284:23116. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.003459. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Dees A, Zahl A, Puchta R, van Eikama Hommes NJR, Heinemann FW, Ivanović-Burmazović I. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:2459. doi: 10.1021/ic061852o. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Zech SG, Eldredge HB, Lowe MP, Caravan P. Inorg. Chem. 2007;46:3576. doi: 10.1021/ic070011u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Caravan P, Cluotier NJ, Greenfield MT, McDermid SA, Dunham SU, Bulte JWM, Amedio JC, Jr, Looby RJ, Supkowski RM, Horrocks WD, Jr., McMurry TJ, Lauffer RB. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:3152. doi: 10.1021/ja017168k. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Eldredge HB, Spiller M, Chasse JM, Greenwood MT, Caravan P. Invest. Radiol. 2006;41:229. doi: 10.1097/01.rli.0000199293.86956.48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Caravan P, Astashkin AV, Raitsimring AM. Inorg. Chem. 2003;42:3972. doi: 10.1021/ic034414f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Castelli DD, Caligara MC, Bota M, Terreno E, Aime S. Inorg. Chem. 2013;52:7130. doi: 10.1021/ic400716c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Beeby A, Clarkson IM, Dickins RS, Faulkner S, Parker D, Royle L, de Sousa AS, Williams JAG, Woods M. J. Chem. Soc. Perkin Trans. 2. 1999:493. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.